Review article: diagnostic and therapeutic approach to persistent abdominal pain beyond irritable bowel syndrome

Funding information:

Under the direction of the authors, writing support was provided by Amy Shaberman, PhD, employee of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Alnylam Switzerland GmbH; editorial assistance in formatting, proofreading, copyediting and fact-checking was also provided by Peloton Advantage

The Handling Editor for this article was Professor Peter Gibson, and this uncommissioned review was accepted for publication after full peer-review.

Summary

Background

Persistent abdominal pain (PAP) poses substantial challenges to patients, physicians and healthcare systems. The possible aetiologies of PAP vary widely across organ systems, which leads to extensive and repetitive diagnostic testing that often fails to provide satisfactory answers. As a result, widely recognised functional disorders of the gut–brain interaction, such as irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia, are often diagnosed in patients with PAP. However, there are a number of less well-known differential diagnoses that deserve consideration.

Aim

To provide a comprehensive update on causes of PAP that are relatively rare in occurrence.

Methods

A literature review on the diagnosis and management of some less well-known causes of PAP.

Results

Specific algorithms for the diagnostic work-up of PAP do not exist. Instead, appropriate investigations tailored to patient medical history and physical examination findings should be made on a case-by-case basis. After a definitive diagnosis has been reached, some causes of PAP can be effectively treated using established approaches. Other causes are more complex and may benefit from a multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterologists, pain specialists, psychologists and physiotherapists. This list is inclusive but not exhaustive of all the rare or less well-known diseases potentially associated with PAP.

Conclusions

Persistent abdominal pain (PAP) is a challenging condition to diagnose and treat. Many patients undergo repeated diagnostic testing and treatment, including surgery, without achieving symptom relief. Increasing physician awareness of the various causes of PAP, especially of rare diseases that are less well known, may improve patient outcomes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Although there is no commonly accepted definition, persistent abdominal pain (PAP) is considered continuous or intermittent abdominal discomfort that persists for at least 6 months and fails to respond to conventional therapeutic approaches.1 This condition is frequently encountered by primary care clinicians, gastroenterologists and pain management specialists. Epidemiological data suggest that prevalence of PAP is 22.9 per 1000 person-years and is similar regardless of age group, ethnicity or geographical region.1 In a recent survey of over 10,000 individuals, 81% reported experiencing abdominal pain in the past week, 60% reported pain onset within the past 5 years and nearly 40% reported pain onset more than 5 years prior.2

Aetiologies vary widely because PAP may arise from many different mechanisms throughout the body.1 The cause of PAP can be classified as organic or functional. Organic aetiologies have clearly identified anatomical, physiological or metabolic causes, whereas functional aetiologies do not despite a thorough diagnostic evaluation. The association of gastrointestinal symptoms and dysfunction with psychological factors supports a gut–brain interaction.3 The Rome IV classification of functional gastrointestinal disorders is based primarily on symptoms related to motility disturbance, visceral hypersensitivity and altered central nervous system processing. The aetiology of PAP may also be based on its origin as follows: (1) originating from abdominal viscera, (2) referred from an extra-abdominal source, (3) genetic origin and (4) centrally mediated disorders.

Diagnosis and management of PAP are challenging and frustrating for patients and physicians due to the poor sensitivity of patient medical history and physical examination, an inconclusive or negative diagnostic work-up and the need for a broad differential diagnosis. Clinicians not only need to recognise somatic abnormalities, but they must also perceive the patient's cognitions and emotions related to the pain.4 By taking adequate time to listen to the patient and perceive psychological factors, clinicians can offer reassurances and suggest behavioural changes, prevent somatic fixations and increase patient satisfaction.5

The most frequent reasons for consulting the gastroenterologist, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)6 and functional dyspepsia7 are the most widely recognised gastrointestinal diseases associated with PAP. These disorders impose a considerable burden on healthcare systems,8 associated with substantial healthcare costs and productivity loss due to high rates of absenteeism.1 Other widely recognised gastrointestinal diseases associated with PAP include inflammatory bowel diseases, chronic pancreatitis and gallstones. The current review provides a comprehensive update on the diagnosis and management of some less well-known causes of PAP.

2 DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

The diagnosis of PAP is based on patient medical history, physical examination, psychological assessment and objective diagnostic tests.9, 10 Given its chronicity, many patients will have already undergone extensive and redundant medical testing. Any change in the description of PAP or emergence of new symptoms should alert the physician to an acute-on-chronic condition (e.g., perforation, obstruction, abscess in the presence of confirmed gastrointestinal disease) or a new condition that warrants investigation (e.g., cancer development). This is especially true as patients age because many gastrointestinal conditions have a peak incidence before the age of 60 years.1 Other ‘red flag’ symptoms include fever, vomiting, diarrhoea, acute change in bowel habit, obstipation, syncope, tachycardia, hypotension, concomitant chest or back pain, unintentional weight loss, night sweats and acute gastrointestinal bleeding.

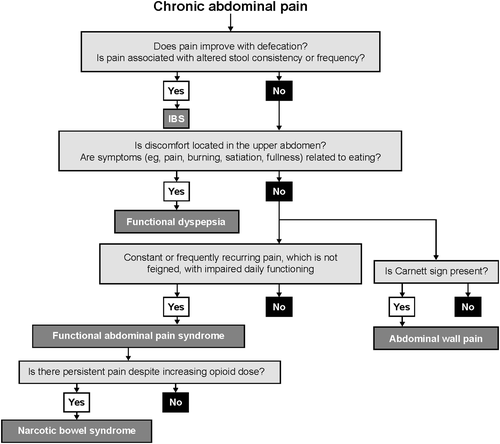

Key information to be obtained during an initial consultation with a patient with PAP should help discern whether the pain origin is organic or functional (Figure 1).11, 12 Organic pain is frequently described using sensory terms such as cramping, burning or stabbing, whereas functional pain has been described using ‘emotional’ terms such as ‘felt too sick to go to work’.13 Organic pain usually occurs in a more systemic manner according to better-defined nerve regions and fluctuates more widely in intensity. A logistic regression analysis identified several criteria that discriminated between organic disease and IBS.14 Age older than 50 years and rectal bleeding were strongly linked to PAP associated with an organic aetiology. Female sex and pain on six or more occasions in the previous year, radiating beyond the abdomen or associated with looser bowel motions, were associated with an IBS diagnosis.

An attempt must be made to identify a triggering event, such as an adverse life event, infection, initiating a new medication or surgical procedure.11 The patient's diet is an important consideration. Recently it has been demonstrated that gastrointestinal symptoms of diarrhoea, constipation, bloating and/or abdominal pain may be associated with an intolerance to fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs).15 These short-chain carbohydrates are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and may induce abdominal pain and bloating. Also, symptoms may be triggered by specific nutrients—for instance, in case of true food allergies—or by histamine-rich nutrients.

Patients with PAP often undergo repetitive diagnostic tests and try various therapies with poor or no clinical benefit. Despite the time-consuming nature, it is important to entirely review all information, along with digestive surgical history, to minimise additional testing.9, 11, 16 Patients with disorders of the gut–brain interaction associated with PAP (e.g., IBS) are at an increased risk of undergoing unjustified surgical procedures,17 such as cholecystectomy (odds ratio [OR], 2.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.87–2.29), appendectomy (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.33–1.56), hysterectomy (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.55–1.87) and back surgery (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.05–1.43).18

While recommendations regarding evaluation of chronic abdominal pain have been published,19 specific algorithms for the diagnostic work-up of PAP do not exist. Instead, appropriate investigations tailored to patient medical history and physical examination findings should be made on a case-by-case basis. Many patients with PAP have repeated standard laboratory testing, upper and lower endoscopic examinations, abdominal ultrasounds and computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdominal/pelvic area. In the absence of alarm features, any additional tests should be ordered in a conservative and cost-effective manner. After excluding common organic aetiologies, some additional clinical situations should be considered before determining a diagnosis of PAP associated with a gut–brain disorder. Overall, patients with PAP who are referred to tertiary centres can be approached with three steps: (1) question the patient at length regarding symptoms and medical history; (2) summarise all previous investigations and treatments and whether they were effective; (3) from the first two steps, deduce the relevant complementary explorations to be performed. Several differential diagnoses are discussed below and summarised in Table 1.1, 3, 11, 12, 20, 70 This list is inclusive but not exhaustive of all of the rare or less well-known diseases potentially associated with PAP.

| Disease | Prevalence | Distinguishing features | Additional signs/symptoms | Pathophysiology | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent abdominal pain linked to a digestive disorder | ||||||

| Eosinophilic gastroenteritis20 | 8.4–28.0 cases per 100,000 | Persistent abdominal pain | Diarrhoea, dyspepsia, nausea and vomiting, atopia, allergy | IgE-dependent and delayed Th2 cell-mediated hypersensitivity | Eosinophilic infiltration in gastric and duodenal specimens | Corticosteroids, mast cell stabilisers, leukotriene antagonists, antihistamines, immune modulators and biological agents |

| Mesenteric panniculitis21 | NA | Abdominal discomfort, fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation | Extensive fibrosis may lead to intestinal obstruction and vascular compression | Unknown aetiology, possible causes include autoimmune processes and low-grade inflammation-stimulating fibrogenic factors | Often found incidentally on computed tomography scan | Immuno-modulators, tamoxifen, progesterone, surgery for extensive fibrosis and bowel obstruction |

| Chronic mesenteric ischaemia22, 25 | 1 in 1000 hospital admissions | Postprandial abdominal pain, weight loss, food aversion, epigastric bruit | Abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or constipation, diffuse atherosclerosis | Atherosclerotic stenosis of one or more mesenteric arteries; less frequently caused by vasculitis | Clinical symptoms, computed tomography angiography, functional test | Smoking cessation, antiplatelet therapy, revascularization |

| Median arcuate ligament syndrome26 | NA | Epigastric pain and tenderness, nausea, vomiting, weight loss and postprandial or exercise-induced abdominal pain, abdominal bruits | NA | Celiac artery compression by the median arcuate ligament | Exclusion of alternative causes of abdominal pain | Surgical median arcuate ligament release and celiac ganglionectomy |

| Postoperative adhesions1, 27, 29 | 45%–90% of patients with persistent abdominal pain | Persistent abdominal pain | Past history of one or several abdominal/gynaecological surgeries open or celio | Caused by manipulation of internal organs during surgery | Exploratory surgery | Laparoscopic adhesiolysis is not recommended |

| Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction30, 31 | 1.5% of general population | Pain localised to the right upper quadrant or epigastrium lasting 30 min or more, biliary pain | NA | Aberrant sphincter physiology leading to increased resistance to bile outflow and subsequent rise in intrabiliary pressure, altered sphincter dynamics | Criteria for biliary pain, elevated liver enzymes or dilated bile duct, but not both | Medications to reduce basal sphincter pressures in sphincter of Oddi, medications to inhibit sphincter motility, possible endoscopic sphincterotomy |

| Pain of gynaecological origin | ||||||

| Endometriosis64, 66 | 7%–10% of women | Chronic abdominal pain, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhoea, infertility | NA | Retrograde menstruation is the most widely accepted pathogenesis | Palpation of pelvic and abdominal area, combined with patient's history; magnetic resonance imaging | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, aromatase inhibitors, oral contraceptive pills, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids; surgical removal of endometrial lesions |

| Chronic abdominal wall pain | ||||||

| Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome32, 35 | 5%–67% of patients referred to specialists | Severe pain in right upper quadrant with a focal area of ≤2 cm in diameter, positive Carnett sign, exacerbated by movement | NA | Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome results from entrapment of an anterior cutaneous branch of a thoracic nerve at the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle | Response to a trigger point injection of local anaesthetic |

Lidocaine patches and trigger point injections (corticosteroid, local anaesthetic or combination) Chemical neurolysis or surgical neurectomy for severe, refractory pain |

| Abdominal muscle pain11, 33, 35 | NA | Persistent abdominal pain exacerbated by sedentary lifestyle | NA | Result of microtrauma, repeated tension or poor posture | Abnormal or asymmetric muscle tone, specific pain points and antalgic posture | Physical therapy |

| Abdominal wall hernia32, 33 | NA | Palpable mass, increased size during coughing, reduced size in supine position | NA | Herniation develops in a natural or iatrogenic weak spot in the abdominal wall | Physical examination with patient standing and supine, ultrasonography or computed tomography for subtle hernias | Surgery (open or laparoscopic) for enlarging or painful hernias |

| Referred osteoarticular pain | ||||||

| Pain of spinal origin11, 32, 33, 70 | NA | Radicular symptoms in dermatomal or myotomal distribution, localised spinal and paraspinal tenderness and myelopathy in severe cases; aggravated by physical activity |

Manifestations related to vertebral osteoarticular damage |

Irritation of the intercostal nerves in the anterior abdominal wall by spinal processes | Physical examination, imaging tests and nerve conduction studies in severe cases | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, muscle relaxants, nerve blocks |

| Pain of costal origin32, 33 | NA | Pain in upper abdomen or chest along lower rib margin, pain may be positional, clicking sound | NA | Occurs when cartilage on lower ribs becomes displaced and irritates the intercostal nerves | Hooking manoeuvre: clinician hooks fingers under costal margin and pulls upward (pain or clicking indicates a positive result) | Surgery (costal cartilage excision) for persistent or severe pain |

| Abdominal pain of systemic origin | ||||||

| Adrenal insufficiency36, 37 |

Primary: 15–22 per 100,000 (Nordic countries), 10 per 100,000 (other European countries), 0.4 per 100,000 (South Korea) Secondary: 14–28 per 100,000 (Spain, United Kingdom) |

Abdominal pain, unintentional weight loss, anorexia, postural hypotension, profound fatigue, muscle pain, hyponatraemia | Skin hyperpigmentation, salt cravings, hyponatremia | Deficient production or action of glucocorticoids, with or without deficiency in mineralocorticoids and adrenal androgens | Paired assay of serum cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone indicating low cortisol concentration and adrenocorticotropic hormone concentration twice the upper reference limit | Glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, adrenal androgen replacement |

| Mast cell activation syndrome38, 41 | Up to 17% of general population | Acute urticaria, flushing, abdominal cramping/pain, diarrhoea, hypotensive syncope or near syncope and tachycardia |

Headache, nausea, non-specific gastrointestinal complaints and life-threatening anaphylaxis Intolerance to multiple foods with histamine-rich nutrients |

IgE-dependent allergic inflammation | Clinical symptoms, often with hypotension, trigger-related substantial increase in serum tryptase levels and response of clinical symptoms to mast cell–stabilising drugs or drugs counteracting the effects of mast cell–derived mediators | Trigger identification and avoidance, antihistamines, leukotriene receptor antagonists, mast cell stabilisers, monoclonal antibodies |

| Systemic mastocytosis42, 44 | 1 in 7700 to 1 in 10,400 | Persistent abdominal pain | Diarrhoea | Somatic KIT gene mutations result in increased production of mast cells and inflammation | Mast cells in extracutaneous organs, atypical mast cell morphology, KIT gene mutation, elevated serum tryptase concentrations | Antihistamines, corticosteroids, interferon-α and KIT tyrosine kinase inhibitors; allogeneic stem cell transplantation for life-threatening disease |

| Hereditary angiooedema: C1 esterase deficiency67, 69 | 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 50,000 | Oedema of skin, abdominal pain attacks (acute and chronic), life-threatening laryngeal oedema | Vomiting, nausea, diarrhoea, intestinal obstruction |

Type 1: deficiency in quantity of functional C1 esterase inhibitor produced Type 2: dysfunctional C1 esterase inhibitor |

Evaluation of patient and family history; review of medications; physical examination with imaging and laboratory tests |

Acute attacks: C1 esterase inhibitors Prophylaxis: attenuated androgens or C1 esterase inhibitors |

|

Persistent abdominal pain of genetic origina |

||||||

| Acute hepatic porphyria45, 49 | 1 in 1700 (acute intermittent porphyria) | Severe, diffuse abdominal pain lasting several days |

Nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, diarrhoea, constipation, hyponatraemia, neurological symptoms |

Haeme biosynthesis enzyme deficiency results in accumulation of neurotoxic haeme precursors, delta-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen Autosomal dominant inheritance |

Elevated concentrations of delta-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen in urine and plasma | Intravenous human hemin, givosiran, liver transplantation in severe cases |

| Lead poisoning50, 51,a | NA | Symptoms similar to those caused by acute hepatic porphyria | Vomiting, constipation, and anorexia; nervous, haematological, and renal impairment, contaminated water consumption | Haeme biosynthesis enzyme deficiency | Lead concentrations in blood | Chelation therapy |

| Ehlers–Danlos syndrome52, 54 | 1 in 150,000 (vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome) | Persistent abdominal pain |

Various gastrointestinal complications Familial history Join hypermobility Skin elasticity |

COL3A1 gene mutation (vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome) results in type III collagen deficiency | Clinical signs, non-invasive imaging, and detection of genetic mutation |

Symptomatic treatment Appropriate precautions during surgery |

| Low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis syndrome55 | 1% of symptomatic cholelithiasis; nearly three times more common in women; occurs in young adults with low or normal body weight | Typical biliary pain with recurrent symptoms after cholecystectomy |

Serious complications: pancreatitis, acute cholangitis, intrahepatic lithiasis Familial history, cholecystectomy in young age |

Mutation of ABCB4 gene that encodes MDR3 protein, reducing biliary phosphatidylcholine concentration and precipitating gallstones | Two of the following criteria: age at onset <40 years; symptom recurrence after cholecystectomy; hyperechogenic intrahepatic foci on ultrasound | Ursodeoxycholic acid |

| Familial Mediterranean fever56, 58 | 1 in 200 to 1 in 1000 in populations of Eastern Mediterranean descent | Intense and diffuse abdominal pain that may last several days; recurrent flares of fever associated with polyserositis |

Tender and tympanic abdomen Familial history Geographical and ethnical origins |

MEFV gene mutations result in increased interleukin-1β production and inflammation Autosomal recessive inheritance |

Clinical findings; detection of MEFV gene mutations |

Colchicine Interleukin-1β inhibitors (colchicine resistance or intolerance) |

| Dysautonomia and centrally mediated disorders of persistent abdominal pain | ||||||

| Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome59, 60 | 500,000 to 3 million (United States) | Severe orthostatic symptoms | Urinary and gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., chronic abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, dyspeptic symptoms) | Visceral hypersensitivity, central sensitisation, somatic hypervigilance, and behavioural amplification | Endoscopic, radiographic, and motility tests | Gastrointestinal symptoms are managed by treating the most prominent symptoms and may include the use of antiemetics, carbidopa, pyridostigmine, tricyclic antidepressants, or other combinations of gut-directed and central agents |

| Narcotic bowel syndrome12, 61, 62 | ~5% of patients who receive opioid therapy | Severe to very severe abdominal pain in presence of escalating or continuous opioid therapy | Bloating, constipation, nausea, and vomiting | Opioid-induced, centrally mediated, visceral hyperalgesia | Based on concurrent symptoms and opioid use | Patient education, opioid detoxification, antidepressants or anxiolytics, psychological interventions |

| Centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome3, 12, 63 | 0.5%–1.7% | Severe abdominal pain; no relationship to eating or bowel movements; impaired daily functioning | NA | Dysregulation of the gut–brain interaction results in central sensitisation and disinhibition of pain signals | Diagnosed using Rome IV criteria | Patient education, behavioural and psychological interventions, pharmacotherapy (generally tricyclic antidepressants), multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation programme |

- Abbreviations: IgE, immunoglobulin E; MDR3, multidrug resistance; NA, not available; Th2, T-helper cell, type 2.

- a Included because of pathophysiology and symptoms similar to those of acute hepatic porphyria.

3 PAP LINKED TO A DIGESTIVE DISORDER

3.1 Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterised by eosinophilic infiltration in the stomach and intestine.20 The estimated prevalence in the United States ranges from 8.4 to 28 cases per 100,000 individuals and is expected to rise with the increasing understanding of the disorder. Occurring at any age, with peaks between the third and fifth decade of life, typical symptoms include abdominal pain accompanied by nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhoea and malabsorption.

The pathophysiology of EGE is not fully understood.20 Hypersensitivity plays a major role, as many patients have a history of seasonal allergies, food sensitivities, asthma and eczema. Both immunoglobulin E (IgE)-dependent and delayed T-helper type 2 cell–mediated hypersensitivity mechanisms are involved in EGE pathogenesis. Laboratory results, radiological findings and endoscopy can help confirm an EGE diagnosis, but it is diagnosed via histological examination of gastric and duodenal biopsies describing an eosinophilic infiltration.20 A specific count of eosinophils per high-power field is required as eosinophil count varies based on age, environmental factors and the anatomic location in the gastrointestinal tract (normal levels in the duodenum: <10 eosinophils per high-power field in children and <19 in adults; caecum: ≤40 eosinophils/high-power field; colon: ≤16 in children and ≤50 in adults).20

The management of EGE includes dietary modification and pharmacological approaches.20 Corticosteroids are the mainstay of EGE therapy. Alternative therapies for intolerance or corticosteroid resistance include mast cell stabilisers, leukotriene-receptor antagonists, antihistamines, immunomodulators and biological agents targeting interleukin-5, tumour necrosis factor α and IgE.

3.2 Mesenteric panniculitis

Typically occurring in late adult life, mesenteric panniculitis is a fibroinflammatory condition of unknown aetiology,21 often found incidentally in patients undergoing cross-sectional CT scan for various indications including abdominal pain. Mesenteric panniculitis usually involves the small bowel and appendix; patients may present with abdominal discomfort, fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and constipation. In patients with extensive fibrosis, shortening and compression of the mesentery and its vessels may occur, leading to intestinal obstruction and vascular compression. However, as mesenteric panniculitis might be found incidentally, it is always important to reanalyse symptoms before attributing them to panniculitis. The pathogenic events suggest a low-grade inflammation in which preadipocytes are more likely to convert over time to macrophages. Increased secretion of proinflammatory adipocytokines initiate and maintain inflammatory changes and are followed by the release of fibrogenic factors, such as transforming growth factor, activating fibroblasts and collagen deposition.

Treatment is not codified, primarily using immunomodulators: corticosteroids, colchicine, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide, as well as tamoxifen and progesterone.21 Patients with extensive fibrosis and bowel obstruction should undergo surgical resection or debulking.

3.3 Chronic mesenteric ischaemia

Chronic mesenteric ischaemia (CMI) is defined as insufficient blood flow through the splanchnic vessels to the gastrointestinal tract, primarily arising from atherosclerotic stenosis of one or more mesenteric arteries for a duration of at least 3 months.22, 25 CMI is caused by occlusive or nonocclusive mesenteric ischaemia.24 While mesenteric artery stenosis occurs in up to 10% of people older than 65 years, CMI has a low incidence overall and accounts for less than one in 1000 hospital admissions for abdominal pain.23 The prevalence of occlusive and nonocclusive ischaemia is unknown.24 Postprandial abdominal pain, weight loss and epigastric bruit compose what is referred to as the ‘classic triad’ of CMI.22, 24, 25 Abdominal pain with postprandial worsening, starting 10–30 min after a meal and lasting 1–2 h, is present in 74%–100% of patients with CMI.24 Diagnosis of CMI is based on clinical symptoms, radiological evaluation of mesenteric vasculature and functional assessment of mucosal ischaemia, if available,22, 25 but remains a challenge because of a differential diagnosis that includes chronic pancreatitis, celiac disease, duodenal ulcers, abdominal malignancies and IBS.24 Thus, patients should be evaluated for potential CMI by a multidisciplinary expert panel comprising a gastroenterologist, interventional radiologist and vascular surgeon for compatibility of history, presence of significant mesenteric artery stenosis on imaging, absence of an alternative diagnosis and, if available, results of a functional test, when being evaluated for potential CMI.24, 25

Management of asymptomatic CMI is performed conservatively with smoking cessation and antiplatelet therapy.23 Symptomatic patients with occlusive CMI are treated with revascularization to alleviate symptoms, improve quality of life, restore normal weight and prevent bowel infarction to improve survival.23, 25

3.4 Median arcuate ligament syndrome

Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) is described by a variety of clinical signs and symptoms, including abdominal pain.26 MALS is associated with celiac artery compression by the median arcuate ligament (a fibrous arch uniting the diaphragmatic crura).26 However, the pathophysiology of MALS is poorly understood, and patients have variable presentations with differing severity and response to treatment.26 Due to the lack of universal diagnostic criteria, the diagnosis of MALS remains one of exclusion (excluding more common, alternative causes of abdominal pain).26 Management of MALS aims to address the hypothesised mechanism through decompression of MAL-associated constriction of the celiac artery, with or without celiac ganglionectomy to target the neuropathy component of pain.26 There are insufficient long-term (>5 years) follow-up data on the efficacy of surgery for treatment of MALS, and a consensus on the optimal surgical approach is lacking.26

3.5 Postoperative adhesions

Surgical procedures may contribute to PAP if postsurgical abdominal adhesions develop.1 Risk factors for adhesion formation include open surgery (vs minimally invasive), use of foreign bodies (mesh) and presence of a contaminated surgical field. However, the incidence of adhesions varies widely in the literature (45%–100%), and causal relationships to abdominal pain have been difficult to prove. No non-invasive tests are available to diagnose abdominal adhesions, but most are identified during exploratory surgery.27, 28 Laparoscopic adhesiolysis has been proposed as a treatment for PAP.28 A systemic review of 25 studies found a positive outcome of adhesiolysis on pain relief, but because the studies lacked controls, these results are hardly discussed.27 However, the only randomised study comparing adhesiolysis to a sham procedure in patients with chronic abdominal pain demonstrated no beneficial effect of adhesiolysis after 1-year follow-up,71 and after 12 years of follow-up, patients with adhesiolysis had more pain, more surgery and more consultations.29 Based on these results, adhesiolysis cannot be recommended.

3.6 Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction is a complicated cause of PAP. It is characterised by symptoms of biliary and/or pancreatic obstruction without identifiable mechanical causes.31 The Rome IV diagnostic criteria include the intensity of pain, justifying emergency room visits and nocturnal awakenings.30 Cholecystectomy is a predisposing factor, and the diagnosis is made either by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and manometry or by hepatobiliary scintigraphy.30, 31 Elevated liver enzymes may also be present.31 Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction can be classified into three types based on the presence of biliary obstruction.31 Conservative management is recommended initially due to the risks involved with invasive approaches.30 To reduce basal sphincter pressures in sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, nifedipine, phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors, trimebutine, hyoscine, butylbromide, octreotide and nitric oxide have been utilised.30 Agents to inhibit sphincter motility include H2 antagonists, gabexate mesylate, ulinastatin and gastrokinetic agents.30 There is consensus that patients with definite evidence for biliary obstruction should be treated with endoscopic sphincterotomy without manometry.30 However, therapeutic response to sphincterotomy may vary between types.31

4 PAIN OF GYNAECOLOGICAL ORIGIN: ENDOMETRIOSIS

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of gynaecological origin that primarily affects women in their reproductive years. The estimated prevalence ranges from 7% to 10% of women.64, 65 Among the theories proposed, the most widely accepted is that retrograde menstruation is associated with the pathogenesis of endometriosis.64 In endometriosis, uterine endometrial cells migrate into the pelvic cavity and form lesions on multiple organs.64, 66 Endometriosis is typically characterised by chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhoea and infertility.64, 65 Furthermore, women with endometriosis often experience gastrointestinal symptoms, such as chronic abdominal pain.64, 66 Diagnosis can begin with a clinical examination involving palpation of the pelvic and abdominal area combined with an assessment of the patient's medical history.64 During the last decades, transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging emerged as diagnostic tools, making diagnosis easier.64 However, small lesions may exist below these techniques' detection thresholds.64 In these cases, evolution of symptoms under treatment could be an argument for a positive diagnosis. Pharmacological and surgical treatment options are available and should be managed by a specialist in this area.64, 66 Pharmacological options to modulate hormonal signalling, reduce inflammation or treat pain include use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, aromatase inhibitors, oral contraceptive pills, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids.64 Surgical treatment involves the removal of endometrial lesions, but a surgical approach can be challenging and may require multiple interventions.

5 CHRONIC ABDOMINAL WALL PAIN

Chronic abdominal wall pain is a common but under-recognised cause of PAP, easily mistaken for a visceral disorder or IBS, and in some cases it can be associated with IBS.33, 72, 73 The prevalence of chronic abdominal wall pain in the general population is unknown, but the specialists to whom patients are referred estimate it at 5%–67%.33 Up to 30% of PAP cases with negative work-up can be attributed to chronic abdominal wall pain.32 The aetiology varies depending on which component of the abdominal wall is affected, but it can often be related to trauma, scar tissue formation or increased pain after sporting activities. In these situations, diagnosis is mainly clinical and treatment is empiric, as there are no randomised clinical studies reported.

5.1 Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome

The most frequent cause of chronic abdominal wall pain is anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES), occurring when an anterior cutaneous branch of a thoracic nerve at the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle is entrapped.32, 33 Intra- or extra-abdominal pressure (e.g., herniation, tissue oedema, fibrosis) or scar formation may cause traction of the nerve, leading to nerve irritation and potentially nerve ischaemia.33, 35

Characteristic features of ACNES include constant or mildly fluctuating severe pain, located most commonly in the right upper quadrant and increased when abdominal muscles are tensed (positive Carnett sign and variations with postural changes).32, 33 An examiner uses the Carnett test to identify the area of tenderness by palpating the abdomen of a supine patient and then applying continuous pressure as the patient contracts abdominal muscles and raises their head and trunk or lower extremities off the table. When the muscles are tensed, the patient is asked if the pain is altered. A positive Carnett sign is a stable or worsening pain at the point of maximal tenderness during contraction. Overall, pain is commonly characterised as sharp and can be pointed out with a fingertip by the patient.74, 75 ACNES is more common in women aged between 30 and 50 years and with various predisposing conditions such as obesity, pregnancy, prior abdominal surgery and sports-related injuries.32, 73 Medical history and physical examination are central to an accurate diagnosis of ACNES, which is supported by a positive Carnett sign and confirmed by an immediate response to a point injection of local anaesthetic. Physical examination is a relatively reliable and simple way to make the diagnosis, which markedly reduces medical costs and avoids repeating diagnostic tests.73 No specific diagnostic tests are available, and a positive response to treatment is probably the only indicator that can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Treatment includes conservative measures, lidocaine patch applications, trigger point injections (corticosteroid, local anaesthetic or combination) and in severe refractory cases, chemical neurolysis or surgical neurectomy.34, 35

5.2 Abdominal muscle pain

PAP may also arise from microtrauma, repeated tension or poor posture, possibly exacerbated by a sedentary lifestyle.11, 33 Clinical diagnosis is based on the presence of abnormal/asymmetric muscle tone, specific pain points and antalgic posture, which is an unnatural position assumed by an individual to minimise or alleviate pain or discomfort (e.g., patient leaning on the painful side). Physical therapy may be helpful in increasing the strength, mobility and flexibility of abdominal muscles to reduce pain intensity.35

5.3 Abdominal wall hernia

Herniation localised to a natural or iatrogenic weak spot on the abdominal wall is a classic cause of PAP.32, 33 Hernias (epigastric, hypogastric, umbilical, inguinal, incisional and Spigelian) are characterised by a palpable mass or fullness that requires a diligent physical examination performed with the patient standing and supine.32, 33 Hernias usually decrease in size when the patient is supine. Conversely, hernia bulging is elicited by coughing. Ultrasonography or CT allows for the detection of subtle hernias (epigastric, incisional and Spigelian). Spigelian hernias are at high risk for strangulation because of their smaller size and may require surgical intervention. Enlarging or painful hernias require surgical repair to relieve discomfort and prevent complications.33

6 REFERRED OSTEOARTICULAR PAIN

6.1 Pain of spinal origin

Often described in diabetic patients, thoracic spinal radiculopathy may manifest as referred abdominal pain due to irritation of the intercostal nerves in the anterior abdominal wall by spinal processes.32, 76 Narrowing of the space where nerve roots exit the spine, due to stenosis, bone spurs, disc herniation or other conditions, may result in radiculopathy. Thoracic spinal radiculopathy is characterised by radicular symptoms with a dermatomal or myotomal distribution, localised spinal and paraspinal tenderness and, in severe cases, myelopathy symptoms.33

Thoracic spinal radiculopathy is typically diagnosed via physical examination (delicately pinching subcutaneous tissues at the level of emerging spinal roots), imaging tests and, in some cases, nerve conduction studies.32, 33 Symptoms can be increased by physical activity11 and are often managed with conservative approaches (physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, muscle relaxants and nerve blocks with anaesthetic agents and/or corticosteroids).76

6.2 Pain of costal origin

Slipping rib syndrome (Cyriax syndrome) is characterised by pain in the upper abdomen or chest along the lower rib margin.32 This syndrome occurs when cartilage on the lower ribs becomes displaced, entrapping and irritating the intercostal nerves. Pain may be positional: a clicking, cracking sound or sensation may occur as the ribs move relative to each other. Slipping rib syndrome is diagnosed using a hooking manoeuvre in which the clinician hooks their fingers under the costal margin and pulls upward; a positive result is indicated by pain or clicking. Usually it can be managed conservatively, but if the condition persists or causes severe pain, costal cartilage excision may be considered.33

7 ABDOMINAL PAIN OF SYSTEMIC ORIGIN

7.1 Adrenal insufficiency

Adrenal insufficiency can be divided into primary (adrenal), secondary (pituitary) and tertiary (hypothalamic) forms.36 It can manifest at any age, but usually presents in people between the ages of 20 and 50 years.36 Abdominal pain is one of the main clinical symptoms of adrenal insufficiency among other symptoms such as weakness, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss orthostatic hypotension and salt craving.37 The nonspecific digestive symptoms, such as abdominal pain, sometimes lead to misdiagnosis of an acute abdomen.77 These digestive manifestations are thought to be a direct consequence of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid deficiency, but the mechanism remains unclear.77 In a cross-sectional controlled study of 119 patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency, 40% of the study population reported abdominal pain at least once a week during the previous 3 months.77 Symptoms were consistent with the Rome IV IBS criteria in 30% of patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency, and IBS-like symptoms were significantly more frequent in patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency than in controls.77 Assessment of adrenal insufficiency by cortisol measurement after tetracosactide is frequent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease after withdrawal of steroid therapy, and this diagnosis should be considered in case of abdominal pain in these patients.78

Adrenal insufficiency is primarily diagnosed by the standard-dose corticotropin test, and prolonged stimulation with exogenous corticotropin is used to differentiate between primary and secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency.37 As adrenal insufficiency is potentially life-threatening, treatment should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed.37 First-line treatment is glucocorticoid replacement, particularly with hydrocortisone.37 Other therapeutic options include mineralocorticoid or adrenal androgen replacement.37

7.2 Mast cell activation syndrome

Mast cell activation disease can be classified into systemic mastocytosis and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS).39 Systemic mastocytosis is a haematological disorder characterised by mast cell accumulation in various organs such as the liver, spleen, bone marrow and gastrointestinal tract42 with both gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal symptoms.79 Gastrointestinal symptoms, mainly abdominal pain and diarrhoea, occur in 60%–80% of cases,42 overlapping with those of functional abdominal disorders (IBS and functional dyspepsia) in which mast cells may be upregulated.79 Some foods may trigger symptoms.80 The estimated prevalence of systemic mastocytosis ranges from one in 7700 to one in 10,400.44

Most cases (>80%) are caused by somatic mutations in the KIT gene, leading to overproduction of mast cells and an inflammatory response.43 Diagnosis is based on criteria developed by the World Health Organization: one major and one minor criterion or three minor criteria must be met. The major criterion is >15 mast cells in an extracutaneous organ. Minor criteria include >25% of mast cells with atypical morphology (spindle-shaped, degranulated and/or multinucleated), KIT D816V mutation, CD2 and CD25 expression on CD117 mast cells and serum tryptase concentrations >20 ng/ml. Mast cell infiltrates are usually identified in the bone marrow.81 Gastrointestinal biopsies can be negative for tryptase expression and may be increased in patients with other conditions, including IBS.81

Treatment of less advanced systemic mastocytosis focuses on trigger avoidance and symptom management using antihistamines, corticosteroids or disodium cromoglycate.42, 43 Treatment of advanced systemic mastocytosis involves antiproliferative agents, including interferon-α and cladribine, or targeted KIT tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation is considered for young and fit patients with a suitable transplant donor.

MCAS is a chronic multisystem disease of abnormal mast cell activation that leads to allergic and inflammatory symptoms.39 Diagnosis is based on the presence of typical clinical signs and symptoms of severe recurrent acute systemic mast cell activation involving at least two organ systems, laboratory-confirmed mast cell involvement and favourable response to drugs with mast cell-stabilising agents or acting against mast cell-derived mediators.40, 82 MCAS can be further classified based on aetiology as either primary (detection of KIT-mutated, clonal mast cells), secondary (detection of underlying IgE-dependent allergy or other reactive mast cell activation-triggering pathology) or idiopathic (absence of a triggering reactive state or KIT-mutated mast cells).40, 83 Gastrointestinal symptoms are common, with abdominal pain as one of the more frequently reported.39 MCAS is often associated with hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hEDS) and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), both of which exhibit extensive gastrointestinal involvement.39 Very recently, some arguments suggest that MCAS is prevalent in patients with long-COVID.84 Mast cell activation triggers include stress, food, alcohol, excipients in medications, infections, altered microbiome and environmental stimuli.39

Treatment of MCAS requires the identification and avoidance of triggers.39 Patients treated pharmacologically are given medications, including non-sedating H1 and H2 histamine receptor antagonists, in a stepwise manner and monitored for benefit and reactions.39 Over-the-counter options include vitamin C, vitamin D and quercetin.39 Second-line therapy includes montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, and/or cromolyn sodium, a mast cell stabiliser.39 Monoclonal antibodies such as omalizumab can also be considered later as pharmacological therapy.39

7.3 Hereditary angiooedema: C1 Esterase inhibitor deficiency

Hereditary angiooedema results from mutations in the C1 esterase inhibitor gene, and can be classified into two types: type 1 is associated with a deficiency in the quantity of functional C1 esterase inhibitor produced; type 2 is associated with dysfunctional C1 esterase inhibitor.67, 68 The most common symptoms of hereditary angiooedema include oedema of the skin, abdominal pain attacks and life-threatening laryngeal oedema.68 The abdominal pain can present as severe acute-onset abdominal pain (typically lasting 1–5 days) or as chronic recurrent abdominal pain, with up to 80% of patients with hereditary angiooedema experiencing recurrent abdominal pain.67, 68 Patients may experience these PAP symptoms without other hereditary angiooedema symptoms (cutaneous or respiratory oedema); thus, diagnosis may be difficult.67

Diagnosis is based on an evaluation of patient and family history and a review of medications to identify angiooedema triggers.67 Additionally, during an acute episode, physical examination with imaging of the abdomen, and laboratory tests, can confirm a diagnosis.67 Imaging results from CT, abdominal X-ray or abdominal ultrasonography may reveal intestinal wall and mucosal thickening, fluid accumulation in bowel loops, obstruction, or ascites, depending on the test.67

The management of hereditary angiooedema can include therapy for acute attacks (C1 esterase inhibitors) or long-term prophylaxis (attenuated androgens or C1 esterase inhibitors).69 Long-term prophylaxis should be individualised to meet patient needs.69 Overall, allergy and immunology specialists should be involved in the management of angiooedema, and appropriate testing should be offered to family members.67

8 PAP OF GENETIC ORIGIN

A genetic origin for abdominal pain is not frequent but should be considered in case of familial history of similar symptoms or when the patient's origin is from an area of high prevalence, such as the Mediterranean Basin

8.1 Acute hepatic porphyrias

Acute hepatic porphyrias (AHPs) are a rare and potentially life-threatening subgroup of hereditary porphyrias characterised by neurovisceral attacks with or without cutaneous manifestations.45, 46 AHPs are transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner,48 and the most frequent porphyria linked to neurovisceral symptoms is acute intermittent porphyria (AIP). The prevalence of AIP in Western populations is approximately one in 1700 individuals, but the penetrance of the gene is low.46 Most patients are female (90%), and age of onset ranges from 18 to 45 years.45

Neurovisceral attacks typically present as severe, diffuse abdominal pain (up to 95% of cases) that increases over several days or recurs over several weeks and is usually accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention and guarding, diarrhoea or constipation.45, 47, 48 Hyponatraemia, hypochloraemia and hypomagnesaemia may develop. Neurological symptoms can range from subtle signs of fatigue to altered mental status and, in severe cases, seizures and stupor.45, 47, 48 Typically, AIP presents in healthy women who report several days of fatigue or mental fogginess with recurrent severe abdominal pain and more severe neurological symptoms.48, 85 As a result, diagnostic orientation is often erratic and delayed by 10 years or more.48 Many patients with AIP are misdiagnosed and undergo unjustified surgical procedures such as appendectomies, cholecystectomies and hysterectomies.86 The central diagnostic clue is the identification of acute or recurrent attack triggers, which commonly include porphyrinogenic medications, alcohol, smoking, low-calorie diets, stress and hormonal changes.45, 47 A recent prospective study in AHP patients, mainly AIP, demonstrated that patients reported abdominal pain (92%) and nausea (85%) during attacks, but 65% of patients also reported chronic symptoms between attacks, mainly pain, nausea, tiredness and anxiety.87

AHPs arise from a deficiency in one of the enzymes in the haeme biosynthesis pathway, resulting in hepatic accumulation and increased excretion of neurotoxic porphyrins and porphyrin precursors: delta-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and porphobilinogen (PBG).45, 48

Diagnosis of AHP is based on elevated concentrations of ALA and PBG in urine and plasma.45, 48 These tests take days to complete and contribute to diagnostic delay, misdirected medical care and poor outcomes. Samples require shielding from light, so consultation with a local porphyrin laboratory on optimal testing is advised for those unfamiliar with testing procedures.88

Lead poisoning is a differential diagnosis because its pathophysiological and symptomatic profiles are very similar to those of AHPs (Table 1).50, 51 Chronic lead intoxication blocks glutathione synthesis in addition to several enzymes involved in haeme synthesis, leading to the accumulation of neurotoxic porphyric derivatives.11, 50 Clinical presentation involves impairment of the nervous, haematological and renal systems, with gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, anorexia, vomiting and constipation) appearing with longer exposures.50, 51 Diagnosis is determined by lead concentrations in blood. Historically caused by lead paint, which has been prohibited in many countries for years, it can occur after drinking water contaminated by corroded lead pipes.89 Patients generally receive chelation therapy and symptomatic treatment as needed.

While patients mostly remain symptomatic, an acute attack of AHP generally warrants urgent treatment with intravenous human hemin.45, 46 Givosiran, a small interfering RNA, was recently approved for the treatment of AHP.90, 94 In a phase 3 trial, givosiran reduced the mean annualised rate of porphyria attacks over 6 months by 74% versus placebo.49

8.2 Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a heterogeneous group of inherited connective tissue disorders characterised by generalised joint hypermobility, skin hyperextensibility and tissue fragility.54, 95, 97 Estimated prevalence is one in 5000.95 Caused by mutations in collagen-encoding genes or genes encoding collagen-modifying enzymes,54 many types have been identified. The most common forms are the classical type, hypermobility type and vascular type, which are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.54, 96, 97 Gastrointestinal symptoms occur in approximately 60% of patients with classical or hypermobile EDS and 50% of those with vascular EDS.95

The hypermobile EDS subtype (hEDS) is autosomal dominant but without any clear genetic mutation.97, 98 The clinical diagnosis of hEDS requires (1) generalised joint hypermobility, (2) at least two features of either systemic manifestations of a more generalised connective tissue disorder, positive family history involving at least one first-degree relative or musculoskeletal complication and (3) absence of unusual skin fragility, exclusion of other heritable and acquired connective tissue disorders and exclusion of alternative diagnoses.99 In a subset of patients, hEDS is linked to a deficiency in tenascin-X, an extracellular glycoprotein matrix that regulates collagen deposition. Associated with a high rate of various functional gastrointestinal disorders, patients with hEDS have significantly more chronic pain, somatic sensitivity and anxiety, along with poorer quality of life compared with patients with other functional gastrointestinal disorders.95, 96, 98, 100 In a French cohort study, IBS, functional constipation and gastroesophageal reflux disease were reported in 48%, 36% and 79%, respectively, of EDS patients (81% had hEDS).96 In a separate case–control study, 40% of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders met criteria for hEDS.98 A large case–control study addressed the prevalence and associations for functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients with hEDS or hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) against age- and sex-matched general population-based controls.101 Almost all patients with hEDS/HSD (98%, n = 591/603) fulfilled symptom-based criteria for Rome IV compared with the population controls (47%, n = 285/603).101 Patients with hEDS/HSD were also significantly more likely to experience abdominal pain at least 1 day per week over the previous 3 months compared with the population controls (75% vs 14%, p < 0.0001).101 Visceroptosis, which is the downward displacement of abdominal organs below their natural positions, has also been reported in patients with hEDS. Visceroptosis can cause kinking of blood vessels and nerves, resulting in severe symptoms.53, 102 Diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms and a positive family history.54

Vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (vEDS) affects an estimated one in 150,000 individuals, is more common in men and is believed to result from heterozygous mutations in the COL3A1 gene, encoding type III collagen.52 Because collagen occurs in most connective soft tissues, spontaneous bowel perforation and intra-abdominal arterial rupture are common complications. Among 133 patients with vEDS, 41% experienced a wide variety of gastrointestinal manifestations, with spontaneous colonic perforations or spleen ruptures, and 53% of patients had recurrent events.

Without any specific evidence-based guidelines for the management of gastrointestinal symptoms in EDS, treatment is supportive in nature and largely focused on alleviation of symptoms with proton-pump inhibitors and antihistamines.53, 95 Appropriate precautions should be taken during surgery and endoscopy in patients with vEDS.53

8.3 Low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis syndrome

Low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis (LPAC) syndrome is associated with mutation of the ABCB4 gene that codes for the multidrug resistance 3 (MDR3) protein.55 Dysfunction of MDR3 reduces biliary phosphatidylcholine concentration, leading to less solubilised cholesterol and precipitation of cholesterol gallstones in the bile ducts. LPAC syndrome occurs in approximately 1% of symptomatic cholelithiasis patients, but it affects about three times more women than men and may account for up to 25% of cases of cholelithiasis in women younger than 30 years. In contrast to classical gallstones, LPAC syndrome occurs primarily in young adulthood and in patients with low or normal body weight. Typical biliary pain is present in over 90% of LPAC syndrome cases.55 Serious complications include pancreatitis, acute cholangitis and intrahepatic lithiasis, which are more frequently observed in men. Diagnosis requires the presence of two of the following three criteria: (1) age at onset younger than 40 years, (2) recurrence of symptoms after cholecystectomy and (3) presence of hyperechogenic intrahepatic foci on ultrasound.

Medical treatment of LPAC syndrome relies on ursodeoxycholic acid, a hydrophilic biliary acid that has multiple mechanisms to potentiate MDR3 and solubilise cholesterol.55 Ursodeoxycholic acid provides rapid relief of symptoms. For patients with hypercholesterolaemia, treatment with statins is preferred over fibrates.

8.4 Familial Mediterranean fever

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is the most common monogenic auto-inflammatory disease described in eastern Mediterranean people,56 affecting one in 200 to one in 1000 persons in this population.58 Characterised by recurrent flares of fever associated with polyserositis,56 patients also experience intense and diffuse abdominal pain often lasting several days. Clinical examinations reveal a tender and tympanic abdomen. Symptoms are sometimes suggestive of a partial occlusion or even ascites, which leads to unnecessary laparotomies.11, 56 On biological examination, C-reactive protein and other inflammatory markers are markedly increased during crisis and rapidly returned to normal value at the end of crisis.103 Secondary amyloidosis is the major long-term serious complication of FMF.

FMF is caused by mutations in the MEFV gene, which encodes pyrin, an element of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex.56 Among 300 identified sequence variants of MEFV, the most common pathogenic variants are M694V, V726A, M680I and M694I; E148Q is the most frequent variant among carriers. FMF is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.57 Mutations in the MEFV gene are associated with increased IL-1β production, which causes excess inflammation.56 Diagnosis of FMF relies mainly on clinical findings, and molecular analysis of the MEFV gene provides genetic confirmation. Only the most frequent mutations are tested during standard genetic testing, meaning that a negative test does not exclude a diagnosis of FMF. In this case, if the clinical history strongly suggests FMF, a positive therapeutic response to colchicine might be necessary to retain a diagnosis.56

Colchicine prophylaxis constitutes the mainstay of FMF management by preventing acute attacks and amyloidosis through reduction of chronic inflammation.56 IL-1 inhibitors, such as anakinra and rilonacept, are beneficial treatment options for colchicine-resistant or colchicine-intolerant patients.

9 DYSAUTONOMIA AND CENTRALLY MEDIATED DISORDERS OF PAP

9.1 Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

Patients diagnosed with POTS have symptoms of orthostatic intolerance for at least 6 months and increases in heart rate of ≥30 bpm within 10 min of standing in the absence of orthostatic hypotension (blood pressure decreases of >20/10 mm Hg).104 POTS is a common cause of chronic orthostatic intolerance, including the severe orthostatic symptoms of tachycardia, light-headedness, blurred vision, tremor and non-orthostatic symptoms. Urinary and gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., chronic abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, dyspeptic symptoms) may considerably diminish quality of life.59 POTS is estimated to affect between 500,000 and 3 million people in the United States,60 principally women aged between 15 and 50 years.59 Abdominal pain has been noted in 70%–80% of patients

POTS is a heterogeneous disorder that may have multiple aetiologies.59, 60 The underlying pathophysiology of gastrointestinal symptoms includes dysautonomia, visceral hypersensitivity, central sensitisation, somatic hypervigilance and behavioural amplification.59 Testing is performed based upon gastrointestinal symptoms and may include endoscopic, radiographic and motility tests. Gastrointestinal symptoms are managed by treating the most prominent symptoms with agents including antiemetics, carbidopa, pyridostigmine, tricyclic antidepressants or other combinations of gut-directed and central agents.

9.2 Association between MCAS, hEDS and POTS

Largely discussed, substantial overlap in symptoms and/or comorbidities exists between MCAS, hEDS and POTS.60 However, while POTS is common and has established diagnostic criteria, diagnostic criteria for MCAS and hEDS are vague. A recent review of the literature concluded that there is a lack of research on any association between the entities, and more stringent diagnostic criteria are needed to minimise false positives.60

9.3 Narcotic bowel syndrome

Narcotic bowel syndrome is characterised by worsening gastrointestinal symptoms in cases of escalating or continuous opioid therapy (Figure 1).12, 61 It is described as chronic, severe to very severe abdominal pain that occurs daily for more than 3 months.62 Additional gastrointestinal symptoms, such as bloating, constipation, nausea and vomiting, may also be present. Estimates suggest that approximately 5% of patients who take regular opioids develop narcotic bowel syndrome,12, 61 but prevalence is probably underestimated given the current epidemic of opioid abuse.

Opioid-induced, centrally mediated, visceral hyperalgesia probably plays a central role in the aetiology of narcotic bowel syndrome,61 with potential mechanisms including activation of bimodal opioid regulatory systems, counter-regulatory mechanisms, neuroinflammation, opioid facilitation and interactions of the N-methyl d-aspartate receptor with opioids at the level of the spinal cord. Management combines patient education (about the paradoxical worsening mechanism) and an opioid detoxification programme, involving tapering or substitution of opioids, concomitant administration of antidepressants or anxiolytics and implementation of psychological interventions. The success of opioid detoxification regimens depends on several factors such as those associated with failure, including history of substance misuse, concomitant personality disorder, a high current opioid misuse measures score and negativity or failure to engage in discussion of detoxification.61, 105 Due to these factors, recidivism rates remain high in the first year following detoxification.

9.4 Centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome (formerly functional abdominal pain syndrome)

Centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome (CAPS) is a functional disorder impairing daily functioning, characterised by chronic or frequently recurring severe abdominal pain, with little or no relationship to events such as eating, defecation or changes in bowel habits.12 Patients with PAP should be screened for psychiatric symptoms, illness-related disability and response to stress, which can impact the ability to cope with symptoms. The prevalence of functional abdominal pain has been reported to range from 0.5% to 1.7%, but this may be overestimated because not all criteria, such as impaired daily functioning, were considered.12

In patients with CAPS, dysregulation of the brain–gut interaction results in central sensitisation with disinhibition of pain signals rather than increased peripheral afferent excitability.3, 63 Notably, CAPS is not associated with visceral hypersensitivity or altered intestinal motility. In a retrospective review of electronic health records from 103 PAP patients, CAPS was identified in 52 (50%) patients. Of these 52 patients, 58% reported bloating and 50% experienced concomitant nausea and vomiting.16 A majority of these patients reported other gastrointestinal disease (65%), other functional diagnosis (85%) and a referral to psychology (55%). These findings are indicative of the frustration and abandonment felt by patients with functional abdominal pain.

CAPS is classified and diagnosed using Rome IV criteria.3 Biological and radiological tests are normal, and patients who are unsatisfied with their treatment seek care from multiple providers, with limited success.12 Physicians caring for these patients also feel frustrated because of lack of specific diagnostic tests and/or patient dissatisfaction. While there are defined criteria for CAPS and other functional gastrointestinal disorders, these disorders cannot be distinguished structurally or metabolically by currently available diagnostic methods.13 The pathophysiology of CAPS and other functional gastrointestinal disorders, such as IBS, is likely similar as well, leading to overlap in comorbidities with other pain syndromes, predisposing life events and treatment responses.13, 106 Thus, management of centrally mediated disorders is a complex process that generally requires a multidisciplinary approach.12

10 CONCLUSION

PAP is a challenging condition to diagnose and treat. Many patients undergo repeated diagnostic testing and treatment, including surgery, without achieving symptom relief. Increasing physician awareness of the various causes of PAP, especially of rare diseases that are less well known, may prompt earlier diagnosis and treatment, which may improve patient outcomes. Some causes of PAP can be effectively treated using established approaches after a definitive diagnosis has been reached. Other causes are more complex and may benefit from a multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterologists, pain specialists, allergists, immunologists, rheumatologists, psychologists, physiotherapists, dieticians and primary care clinicians.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Benoit Coffin conceived the idea to develop the manuscript. Benoit Coffin and Henri Duboc contributed equally to the drafting and critical review and revisions of all drafts of the manuscript and approved the final version.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Declaration of personal interests: B Coffin has served as a speaker for Kyowa Kyrin and Mayoly Spindler and as an advisory board member for Sanofi and Alnylam. H Duboc: None.

AUTHORSHIP

Guarantors of the article: Benoit Coffin and Henri Duboc.