Identifying language disorder in bilingual children aged 2.5 years requires screening in both languages

Funding information

This research was mainly funded by Uppsala County Council Grant for healthcare research. In addition, grants were provided by the Gillbergska Foundation in Uppsala, the Clas Groschinsky Foundation, the Solstickan Foundation and Queen Silvia's Jubilee Fund.

Abstract

Aim

Bilingual children are at risk of being overlooked for early identification of language difficulties. We investigated the accuracy of four screening models for children aged 2.5. The first model screened the child using their mother tongue, the second screened in Swedish, and the third screened in both languages used by the child. The fourth model consisted of direct screening in Swedish and using parental information about the child's language development in their mother tongue.

Methods

Overall, 111 bilingual children (51% girls), 29-33 months, were recruited from three child health centres in Gävle, Sweden, from November 2015 to June 2017. All children were consecutively assessed by a speech and language pathologist, blinded to the screening outcomes.

Results

Developmental language disorder was confirmed in 32 children (29%). Only the third model, based on direct assessment using the two languages used by the child, attained adequate accuracy; 88% sensitivity, 82% specificity, 67% positive and 94% negative predictive values.

Conclusion

Bilingual children should be screened directly in both their languages in order to achieve adequate accuracy. Such screening procedure is particularly important for children from families with low socio-economic status living in complex linguistic environments.

Abbreviations

-

- DLD

-

- developmental language disorder

-

- SLP

-

- speech and language pathologist

Key Notes

- Previous studies demonstrated the need for validated assessment instruments for identification of language disorders in bilingual children.

- The procedure combining the two languages used by the child identified language disorders in bilingual children aged 2.5 years compared with the procedure using only one language.

- Child healthcare nurses should screen bilingual children in both their languages in order to evaluate their full language capacity compared to monolingual children.

1 INTRODUCTION

Research in language and communication disorders mainly involves monolingual individuals. Guidelines on clinical practice involving bilingual individuals are limited. However, bilingualism is prevalent worldwide and half of the world's population speak more than one language.1 In this study, children are considered to be bilingual when exposed to two or more languages regularly. The mother tongue is referred to as the child's first language and Swedish as the second.

Language development in typically developing bilingual children occurs at similar pace as in monolingual children, in both their languages.2-4 However, bilingual children with a language disorder develop both their languages at a slower pace than bilingual peers with typical language development.5 Language development in bilingual children may be unfavourably affected by external factors. These include socio-economic conditions6 or exposure to several languages in the absence of competent speakers of these languages.7 This is referred to as a ‘complex linguistic environment’ in the present study.2

The present study uses the term developmental language disorder (DLD). This signifies difficulties in expressing and understanding language to such an extent that everyday life and social relations are affected. In bilingual children, DLD always occurs in both their languages, and the prevalence is supposed to be the same as for monolingual children.2, 8 Moreover, DLD occurs in 7%-14% of children; however, the prevalence is considerably higher in socio-economically disadvantaged groups.9 DLD may also coincide with other developmental disorders. Furthermore, it does not require a mismatch between verbal and non-verbal skills as did the previous term for specific language impairment.10 In combination with bilingualism, DLD has scarcely been researched, particularly within child health care.

In Sweden, all children between 0 and 5 years of age are offered health check-ups and diverse developmental assessments regularly, free of charge. A screening procedure to detect language disorder in children aged 2.5 years is included in the Swedish child health programme. One-third of all preschool children in Sweden are bilingual.11 With an increasing number of bilingual children, the demands on the child healthcare services to provide good health on equal terms for all children are amplified.12 A national study found that nurses at child health care screened bilingual children in their second language, Swedish.13 If the child had poor skills in Swedish, the nurses mitigated the screening demands or based the language assessment on information received from the parents regarding the child's language use. Consequently, there is a risk that DLD in bilingual children will go unnoticed. This is unfortunate because severe language difficulties may be an early marker of other developmental disorders10 and early effective intervention is available.14, 15 Therefore, validated language screening designed for bilingual children, with clear guidelines on referral and follow-up, is needed. The language screening used in the present study has been evaluated for monolingual children aged three16 and 2.5 years.17

The aim of this study was to investigate whether the language screening would detect DLD in bilingual children aged 2.5 years. We also aimed to examine whether bilingual children with DLD could be identified using only one of their languages in the screening.

We evaluated four models: model one was based on screening results using the child's mother tongue, and model two was based on screening results using Swedish. In model three, the direct results of the screenings using both languages of the child were combined to obtain an overall outcome. Model four was based on a combined result from screening in Swedish and using parental information about the child's language development in their mother tongue.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

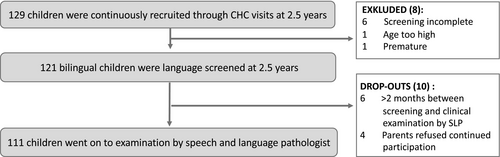

Children were recruited from three child health centres in the city of Gävle, Sweden. The child health centres were located in areas where about 40%-50% of the families were foreign-born. Gävle has 75 000 inhabitants, including 7000 children aged 0-5. A total of 129 bilingual children were recruited consecutively from November 2015 to June 2017, at the time of the regular 2.5-year health visit. Only children born after gestational week 37 and without any known disability were included. Children whose parents had Swedish as mother tongue were excluded. Before the clinical validation, 18 children dropped out (Figure 1). The remaining 111 (51% girls) were between 29 and 33 months old at the time of screening. Parental languages were Somali (n = 42), Arabic (n = 40), Kurmanji (n = 11), Farsi (n = 7), Sorani (n = 6) or Turkish (n = 5). All children except one attended preschool, but 54% of them did not attend regularly. Sixty per cent attended preschools, where many different languages were represented (Table 1). The mother's educational level was compared with that of all foreign-born women in Sweden with a permanent residence permit. The maternal educational level in the sample was significantly lower than that of foreign-born women aged 24-44 in the general population (P < .01).18

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Maternal education (n = 110) | |

| Illiterate | 11 (10%) |

| Elementary school | 35 (32%) |

| Secondary school | 36 (33%) |

| College or university | 28 (25%) |

| Parents who have lived in Sweden more than 5 years (n = 59) | |

| Need for an interpreter | 39 (66%) |

| No need for an interpreter | 20 (34%) |

| Child's attendance at preschool (n = 110) | |

| Regular attendance 15 h/wk, 18 mo or less | 36 (32%) |

| Regular attendance 15 h/wk, 18 mo or more | 15 (14%) |

| Sporadic attendance or attending few hours, less than 15 h/wk | 59 (54%) |

| Proportion of children with another mother tongue at the child's preschool (n = 110) | |

| Less than 20% | 7 (6%) |

| 20%-49% | 14 (13%) |

| 50%-79% | 23 (21%) |

| 80% or more | 66 (60%) |

Note

- Total of 111 children. Background information was missing for one child.

2.2 Material

The screening consisted of an assessment of language comprehension and an observation of language production. The screening was conducted in the child's mother tongue and in Swedish. The results were analysed for this study according to four models: the child's mother tongue (model one), Swedish (model two) and a combination of both languages (model three). Lastly, screening in Swedish was combined with parental reports regarding the child's language development in mother tongue (model four). In order to minimise the learning effects between tests, the comprehension items were replaced by new items of equal difficulty translated into the six languages included in the study (Table 2). The child indicated understanding with a gesture or verbally. There were no formal grammatical requirements for two-word utterances because grammatical parts are often given by the context. All type of constituents, which the child put together in order to express itself while interacting with others, were approved as two-word utterances. For example, ‘daddy car’ may stand for ‘daddy is driving the car’, ‘Up mummy’ stand for ‘mummy lift me up’ and ‘no eat’ may stand for ‘I don't want to eat’ depending on the context. However, echoing and frozen phrases, meaning a fixed combination of two or more constituents, which did not occur separately, like ‘good morning’ or ‘bye-bye’ did not count as two-word utterances. Combinations of words or constituents in two languages were approved. In accordance with existing clinical routine, parents completed a questionnaire with focus on production and comprehension in the child's mother tongue (Table 2). Intelligibility of the child's speech in both languages and parental concerns about the child's language development were also recorded. The test administrators also recorded the child's ability to cooperate during the comprehension part of the screening.

| Screening | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables | Screening in Swedish | Screening in the child's mother tongue | Screening criteria to be referred to SLP |

|

Comprehensiona |

1. What can you wear? (cap) | 1. What can you eat? (banana) | Fewer than 3 correct answers either in screening in Swedish or in screening in the mother tongue. |

| 2. What can you use when you drink? (mug) | 2. What can you use when you sit? (chair) | ||

| 3. What can you do with this? (ball) | 3. What can you do with this? (toothbrush) | ||

| 4. What can you do with these? (crayons) | 4. What can you do with these? (comb/brush) | ||

| 5. Give me the car and the capb | 5. Give me the ball and the chairb | ||

| Productionc | The nurse/bilingual pedagogue has to hear the child speak in multi-word utterances | Does not speak in at least sentences of two words in any language | |

| Parental questions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables | Language development in the child's mother tongue | Screening criteria to be referred to SLP |

| Comprehension | Does your child understand requests, for example ‘can you get the spoon on the table in the kitchen’—without you showing what you want in any other way? | No, does not understand |

| Productionc | Does your child use short sentences of at least 2-3 words? The pronunciation and grammar do not have to be correct. For example, 2 words: ‘look car’, ‘teddy gone’, ‘daddy shoe’, ‘there dog’ or 3 words: ‘dog sleep there’, ‘I want play’. | No, does not combine words to make sentences |

- Abbreviation: SLP, speech and language pathologist.

- a Verbal response was not required. The child could also show adequate understanding by using gestures.

- b The command was given as one statement without any reinforcement with gestures. The child had to give the test leader both pictures after the instruction.

- c Combinations of words in two languages were also approved.

The examination by the speech and language pathologist (SLP) included a structured observation during a play session of the child's ability to communicate and talk in multiword utterances. To examine language comprehension, the Swedish version of the receptive part of Reynell Development Language Scales III19, 20 was applied, here, referred to as Reynell. In order to minimise variations in interpretation, the questions in Reynell were carefully translated into the six languages included in the study. Preschool teachers provided information on the child's language development, ability to play and participation in everyday social activities. The parents reported on the child's medical background, family history, and early language and communication development.

2.3 Procedure

The screening in Swedish was performed by 10 nurses who had been working in child health care for at least 1 year. Furthermore, 12 bilingual preschool staff were trained to be able to perform the screening in the child's mother tongue without the nurse's participation. They also helped to interpret the test items during the clinical testing of the child in his/her mother tongue, which was performed by the SLP. The nurses and bilingual staff took part in a 2-day workshop on DLD and screening, including practical exercises.

The screening took place during two sessions within 2 weeks at the child health centre. At the first visit, the nurse performed the screening in Swedish. The parents answered questions about the child's language development in both languages. At the second visit, one of the bilingual staff performed the screening in the child's mother tongue. The parents answered additional questions about their education, the child's preschool setting and the child's exposure to both languages. A research assistant received all screening protocols and thereafter blinded the identity of the child. The blinded protocols were forwarded to the SLP (first author, LN), who scored the protocols according to the screening criteria (Table 2). In order to pass the screening, the child was required to pass the comprehension and the production criteria (Table 2). If the child did not cooperate in either of the screenings, he/she was classified as positive.

All children were clinically examined by the SLP (LN) within 2 months from the screening. The clinical examination took place at the child's preschool during two sessions: one in Swedish and the other in the child's mother tongue, with an interval of 2-4 weeks. Thus, all children were assessed four times in total, twice in their first language and twice in their second language, Swedish.

2.4 Statistics

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and positive and negative likelihood ratio were calculated with 95% confidence intervals using MedCalc in order to determine screening accuracy (MedCalc Software Ltd.). Associations between parents' education and clinical outcomes were calculated by logistic regressions in SPSS, version 24 (IBM Corp.).

2.5 Ethical considerations

Information about the study and consent forms, both in Swedish and translated into the family's language, were sent to parents prior to their child's routine health visit at 2.5 years. During the health visit, the nurse also provided oral information. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala (dnr 2015/199).

3 RESULTS

The clinical examination identified DLD in 32 children (19 boys), corresponding to a sample prevalence of 29% (95% CI 21-38). A total of 28 children (25%) found to have DLD were suspected of having difficulties caused by developmental disabilities, for example neurodevelopmental diagnoses. Severe difficulties were confirmed in 21 children. In total, 14 parents (13%) expressed concerns about the child's language development in the mother tongue. The SLP confirmed these concerns in 12 cases.

Of the 111 children screened, 11 (10%) did not cooperate, neither in Swedish nor in their mother tongue. Among non-cooperating children, eight were assessed as having DLD by the SLP.

Table 3 shows the screening accuracy for the four models, including and excluding children who did not cooperate. Models one and two yielded many false positives resulting in low specificity, as well as a low positive predictive value. Positive likelihood ratio, that is the probability that a child with a true DLD will screen positive, was also low. Model four yielded few true positives but many false negatives. However, although model four had excellent positive predictive values, the sensitivity was very low. Model three stood out as the best model, with appropriate values in all six aspects. This was true both with, and without, children that did not cooperate.

| n | TP | FP | FN | TN | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | LR+ | LR− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 111 | 29 | 22 | 3 | 57 | 91 (75-98) | 72 (61-82) | 57 (48-66) | 95 (87-98) | 3.3 (2.2-4.7) | 0.13 (0.04-0.38) |

| Model 2 | 111 | 31 | 52 | 1 | 27 | 97 (84-100) | 34 (24-46) | 37 (33-41) | 96 (79-99) | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | 0.10 (0.01-0.64) |

| Model 3 | 111 | 28 | 14 | 4 | 65 | 88 (71-96) | 82 (72-90) | 67 (55-77) | 94 (87-98) | 4.9 (3.02-8.08) | 0.15 (0.06-0.38) |

| Model 4 | 101 | 8 | 1 | 19 | 73 | 30 (14-50) | 99 (93-100) | 89 (51-98) | 79 (75-83) | 22 (2.9-167) | 0.71 (0.56-0.91) |

| Excluding children who did not cooperate | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | 92 | 14 | 18 | 3 | 57 | 82 (57-96) | 76 (65-85) | 44 (33-55) | 95 (87-98) | 3.4 (2.2-5.4) | 0.23 (0.1-0.7) |

| Model 2 | 82 | 14 | 40 | 1 | 27 | 93 (68-100) | 40 (28-53) | 26 (22-31) | 96 (80-99) | 1.6 (1.2-2.0) | 0.17 (0.02-1.12) |

| Model 3 | 100 | 20 | 11 | 4 | 65 | 83 (63-95) | 86 (76-93) | 65 (51-76) | 94 (87-98) | 5.8 (3.2-10.2) | 0.19 (0.08-0.48) |

| Model 4 | 74 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 62 | 17 (2-48) | 100 (94-100) | 100 | 86 (83-89) | -a | 0.83 (0.65-1.07) |

Note

- Model 1 comprises screening in the child’s mother tongue. Model 2 comprises screening in Swedish as the child’s second language. Model 3 is the combined result of screening in the child’s both languages. Model 4 is the combined result of screening in Swedish (Model 2) and parental information about language development in the child’s mother tongue. Parental information was missing for 10 children. Clopper-Pearson 95% confidence intervals are presented within parentheses.

- Abbreviations: FN, false negative; FP, false positive; LR−, negative likelihood ratio; LR+, Positive likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

- a Cannot be computed because that would involve division with zero.

Of the 32 children with confirmed DLD, 18 were identified using the criteria for comprehension and production. The comprehension criteria identified eight additional children, while the production criterion identified two children when standing alone. The remaining four children with confirmed DLD had passed the screening. Information provided by the parents often supported the nurses' assessment, but did not improve the outcome of model three.

Maternal educational level showed no significant association with the clinical outcome (P = .321).

4 DISCUSSION

The language screening used in the present study had previously been validated for monolingual children aged 2.5 years.17 In this study, we investigated whether the screening would also predict risk for DLD in bilingual children. Accuracy of four screening models was tested, based on different combinations of the child's mother tongue and the second language, Swedish.

4.1 Main findings

Screening in one of the child's languages only, as demonstrated in models one and two, led to many false positives. However, the number of children identified as being positive decreased significantly when both the mother tongue and Swedish, presented as model three, were used for screening. Moreover, specificity and positive predictive value increased radically with model three, which is also supported by previous studies.4, 21 Screening in Swedish, combined with information from parents about the child's mother tongue, presented as model four, yielded a high specificity but a very low sensitivity. In other words, numerous children with DLD passed the screening, while children with typical language development could be correctly identified. Many nurses conduct the screening in this way today. The shortcommings of model 4, is unfortunate because screening in the child's mother tongue using the parental reports could have been faster than a full bilingual screening.

Information provided by parents about the child's language development in their mother tongue indicated that they had poor ability to identify DLD in their child. However, they were better at identifying a child that did not have language difficulties. Hence, it is important to follow-up on parental concerns; however, it would lead to massive under-referral standing alone.

4.2 A complex linguistic environment

We found that DLD was three times as frequent among bilingual children in this study than in monolingual peers from the same district.17 Bilingual children also had a higher risk of severe language difficulties compared to monolingual peers.22, 23 Similar to monolingual children aged 2.5 years, DLD was overrepresented among non-cooperating bilingual children.17

Bilingualism per se does not lead to higher prevalence of DLD.2 However, a background with multiple risk factors has negative impact on language development. Bilingual children living in segregated areas may develop their second language at a slower rate, while the development of their mother tongue tends to be less affected.24 Bilingual school-aged children from socio-economically disadvantaged environments, who attended schools in these areas, displayed lower test results in their second language than bilingual children from socio-economically advantaged environments.25

The receptive part of the Reynell test, used by the SLP in this study, has been validated for Swedish speaking bilingual children aged 2.5-3.5 years.19, 26 The results showed that the monolingual norms could be useful for bilingual children, although they generally score lower than monolingual peers. However, this was taken into account by the SLP during the assessment. Moreover, because children were assessed in both their languages, the risk for overidentification was low. Instead, the high prevalence of severe DLD in this study may have been related to complex mechanisms associated with the migration process,27 and opportunities for migrants to integrate into society.

First, all children in this study had a second language acquisition with a varied and often insufficient exposure depending on their preschool. Half of them went to preschool sporadically, and 60% of all children (n = 66) attended preschools where more than 80% of the children had other mother tongues than Swedish (Table 1). Consequently, a majority of them were exposed to a complex linguistic environment, surrounded by many languages and a lower quality and quantity of language input.28 It is well known that such factors aggravate any existing DLD in bilingual children.2, 8

Second, the impact of factors associated with socio-demographic conditions and migration on the child's language development should be considered. A Swedish epidemiological study highlighted specific risk factors for bilingual children.22 One example is parental need to have an interpreter despite several years of residence in Sweden, which may serve as proxy for difficulties with literacy or language. About 66% of parents who lived in Sweden for more than 5 years, reported need for an interpreter when they visited health care (Table 1).

Finally, low socio-economic status has been considered as a factor affecting children's linguistic and cognitive ability.6, 29 The mothers in this study displayed considerably lower education compared to the immigrant female population of the same age in Sweden; about 10% of mothers had never attended school. However, in this study, parents' educational level showed no significant association with the clinical outcome on the individual level. Here, we studied a group of less socio-economically advantaged bilingual children. Perhaps, the prevalence of DLD would have been lower for bilingual children in affluent areas with parents having higher education. However, the findings indicate clinically relevant problems in multicultural areas of low socio-economic status.

4.3 Clinical implications

Bilingual children are a very heterogeneous group, with different family backgrounds, and social and linguistic circumstances. All these aspects have significant influence on language development and on severity of DLD.7 Almost every third bilingual child, growing up in a low socio-economic environment, displayed DLD in our study. Consequently, the screening should always be conducted in both languages used by the child, particularly if the child does not pass the screening in one language. The current procedure to screen the child in his/her second language, Swedish, combined with information received from parents is not a reliable enough approach. However, now, there is a validated test for bilingual children at 2.5 years of age.

Given that a high percentage of children with suspected DLD in early age have shown neuropsychiatric disorders at school start,30 early detection and support are vital. Educational efforts are needed for child health services related to language assessment, language development, risk factors and signs of DLD. The linguistic environment provided by the preschools constitutes a modifiable risk factor amenable to political decisions on improved quality.

To determine whether different living conditions and social class affiliation influence language development in bilingual children, there is a need for future studies. In addition, diagnostic accuracy is more challenging with younger children compared to older.17 Future studies should therefore determine later outcomes of bilingual children diagnosed with DLD at age 2.5.

4.4 Strengths and limitations

This is the first study of bilingual children in which all screened children were assessed in both their languages, followed by a blinded clinical examination as a gold standard for DLD diagnosis. A further strength was that the children were not selected but consecutively recruited during 20 months. The study followed the same procedure and recruited children from the same child health centres as a previous study of monolingual children,17 allowing for some comparisons between the studies.

Furthermore, the Reynell test used by the SLP in the present study had previously been evaluated for bilingual children in a number of studies. The translations of Reynell and items in the screening regarding comprehension were reviewed by the assessing SLP together with bilingual staff and others with diverse languages. As a rule, translation of tests is not recommended and is usually considered a limitation. The children in this study, however, were given the test items by trained bilingual staff using carefully controlled translations of the items. Hence, this procedure is likely to have mitigated this limitation. The fact that the evaluation of the screening outcomes in either language was performed by an SLP, not by a nurse at the child health centre, has both advantages and disadvantages. It ensured conformity and that the evaluation was transparent and unaffected by the wait-and-see strategy found in earlier studies.13 At the same time, it constituted a deviation from the ordinary procedure of how the screening is evaluated.

The relatively small sample size, the restriction to six languages and the fact that all three child health centres recruiting children served low socio-economic areas limit the generalisability of the study. Some restriction on the number of languages is clearly needed, and the six languages included are presently the most frequently spoken by immigrant families in the region.

5 CONCLUSION

The language screening identified bilingual children with severe and moderate difficulties at 2.5 years. The rate of DLD was high, with a sample prevalence of 29%. The number of false positives was reduced when the child was screened using both his/her mother tongue and the second language, Swedish. This procedure is highly relevant for screening of bilingual children from socio-economically disadvantaged areas who are at an increased risk of suffering from severe DLD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge all children and parents for participating in this study. We also acknowledge the nurses, leaders at the child healthcare unit in Gävle, and SLP colleagues at Gävle hospital for their help. Special thanks to Karin Sundell, coordinator in Gävle municipality, and the bilingual staff. Finally, many thanks to research assistant Antonia Tökés.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The first author (LN) works in the Uppsala Child Health Unit where the language screening at 3 years, in its original version, was developed and is still used. The other authors report no conflict of interest.