Early childhood social determinants and family relationships predict parental separation and living arrangements thereafter

Funding information

The Danish National Research Foundation established and funded the Danish Epidemiology Science Centre that initiated the Danish National Birth Cohort. Additional financial support for the DNBC was obtained from the Pharmacy Foundation, the Egmont Foundation, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Augustinus Foundation, and the Health Foundation. The 11-year follow-up was funded by the Danish Medical Research Council, the Lundbeck Foundation and a strategic grant from Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen.

Abstract

Aim

Parental separation has been associated with poor mental health in children with better outcomes in children living in joint physical custody compared with those living with one parent after the separation. In this study, we investigated socioeconomic and relational predictors in early childhood of later parental separation and family arrangements thereafter.

Methods

This study included 34 768 children from the Danish National Birth Cohort, who were living with both parents at the 6 months’ data collection and followed up in 2010-2014 at age 11 years. Questionnaire data from the two data collections were linked with population registers in Statistics Denmark about parental income, education and psychiatric care and analysed in logistic regression models.

Results

Socioeconomic indicators of the family and parental psychiatric disorders before birth of the child and family relationships in infancy predicted parental separation at age 11 year. For children with separated parents, a high family income and a high parental educational level were the main predictors of living in joint physical custody at the 11-year follow-up.

Conclusion

Socioeconomic living conditions predict parental separation as well as living arrangements thereafter. Studies of consequences of living arrangements after parental separation should account for family factors preceding the separation.

Key notes

- More than one third of children in the Nordic countries experience parental separation during childhood.

- Parental separation is more common in families where parents are young, have low household incomes, low educational levels and a psychiatric disorder prior to the birth of the child.

- Joint physical custody is more common after parental separation if parents have high income and a high educational level.

1 INTRODUCTION

More than one third of children in Scandinavia experience parental separation before age 18 years. Multiple studies have shown that children with separated parents score lower on measures of academic achievement, conduct, psychological adjustment, self-concept and social relationships. These risks also carry over to health in young adulthood.1-3 Loss of material, social and financial resources have been found relevant to explain this higher risk. Loss of parental engagement, mostly from the father, is another risk factor. The lower well-being may also be associated with parental health and family relational problems before as well as after the separation.2, 3

Lately, research has moved from studying how parental separation per se affects children, to the analysis of children's health and well-being in different living arrangements after parental separation. Shared parenting, or joint physical custody, refers to a practice where children with non-cohabiting parents live alternating and essentially equally much with both parents, for example, 1 week with the mother and the next with the father.4 Joint physical custody is increasing in many Western countries and is particularly common in the Nordic countries.4 The share of joint physical custody among children with separated parents has been reported to be 25% in Denmark and Norway and about 35%-40% in Sweden.4 Reviews by Nielsen5 and Fransson et al4 and a meta-analysis by Baude et al6 show less symptoms and higher wellbeing in children in joint physical custody than among those in lone care settings. However, in comparison with children in families where parents have not separated, children in joint physical custody have usually been reported to have slightly higher levels of symptoms and slightly lower levels of well-being.4-6 One analysis of data from 36 countries also found higher mean levels of life satisfaction in children in joint physical custody compared with those in lone care.7 However, Vanassche et al8 did not find any difference in quality of life and depressive symptoms between those in joint physical custody and lone parent care, after controlling for confounders. Importantly, these studies are all cross-sectional and lack data about risk factors in the family preceding the separation. Moreover, studies in the field have been unsuccessful in identifying the mechanisms behind the differences in wellbeing of children in different living arrangements. Socioeconomic, parental factors and children's satisfaction with their relationships to the parents have been hypothesised to be involved.9, 10

In this study, we wanted to investigate how selected socioeconomic indicators and parental mental health before the birth of the child and/or family relations in infancy predicted parental separation before the age of 11 years and whether these determinants also predicted living arrangements after parental separation.

2 METHODS

We used data from the Danish National Birth Cohort. The study design and response rates of this cohort have been described elsewhere.11 Women from all regions of Denmark were recruited at their first pregnancy visit to their general practitioner. In total, 92 274 women and their 100 415 pregnancies were recruited, which has been estimated to represent approximately 60 per cent of all invited pregnancies.11 When the child was 6 months old, the women were invited for a computer-assisted telephone interview. In the period from 2010 to 2014, each child was then invited by letter to respond to an internet-based follow-up questionnaire (DNBC-11). The parent with whom the child lived the majority of the time was invited along with the child. Eighty-two per cent of the children were 11 years old at the time they were invited. All participants provided written consent at recruitment and approval for the 11-year follow-up was obtained from the Danish Data Protection Agency (2009-41-3339).

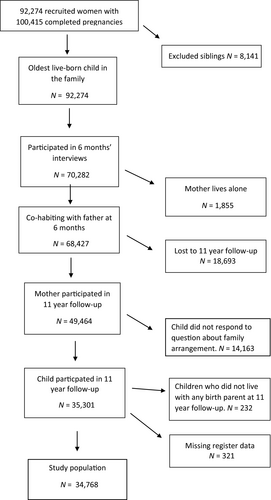

In total, mothers of 49 464 children, corresponding to 52.6 per cent of the original cohort participated in the data collection at 11 years. Of these children, 34 678 participated in a way that fulfilled the criteria of this study. The selection process and reasons for exclusion are presented in Figure 1. A descriptive comparison of study participants and dropouts is presented in Table S1. More details on the study design and questionnaires are available at dnbc.dk and in past publications describing11 and using12, 13 this study.

2.1 Parental separation and children's living arrangements at age 11 years

This study had two main outcomes: parental separation and type of living arrangements after parental separation, based on information collected at the 11-year follow-up. These outcomes were based on one survey item in the child questionnaire that asked which adults the children lived with all, or most, of, the time. This item had nine possible response categories that were merged into four categories in this study; (a) with both (with both my parents); (b) joint physical custody (I split my time equally/almost equally between my mother and my father); single parent (with my mother; with my father); stepfamily (my mother and her new boyfriend/husband; my father and his new girlfriend/wife). The 228 children who responded that they were not living with any of their birth parents (foster family; live in a children's home; other) were excluded from the study population (Figure 1).

2.2 Items from the DNBC at child age six months

Covariates associated with maternal depressive symptoms and family relationships before separation were collected at the 6 months interview. Depressive symptoms were measured using eight items from the SCL symptoms checklist-92,14 where having at least two symptoms was categorised as yes. Family relationships and the perception of the family's economic situation were measured with four questions to the mother. The questions dealt with relational problems between herself and the baby, the relation between the father and the infant, whether the relation to the father was a burden and whether the economic situation of the family was a burden. These questions had three possible responses; no, some, yes.

2.3 Register data

In addition to information provided by mothers and children in the cohort, the present study also made use of covariates based on data from several Statistics Denmark Registers; Danish Medical Birth Registry,15 Income Statistics Register,16 the Population Education Register,17 Central Population Register (CPR) and the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register, linked through the unique person identifier existing in these registers.

Maternal age and age and sex of the child were obtained from the Danish Medical Birth Registry. Information on disposable income of the family and parental education was collected the year before the child was born and was retrieved from the Income Statistics Register and the Population Education Register, respectively. Disposable household income was equalised annually in the entire cohort and parental education represents the highest attained. Any contact with secondary mental health services before the birth of the child was retrieved from the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register from 1977 onwards and was dichotomised as yes or no.18

2.4 Analytical design

Firstly, we analysed predictors of parental separation in the entire study population. We calculated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) in two logistic regression models with parental separation before the age of 11 as the outcome variable. The two models followed the reversed order of the two data collection points. The first model included the items from the 6 months interview adjusted for gender, while the second model also included register indicators of parental psychiatric disorders, household income in quintiles and education prior to the birth of the child. Secondly, we calculated OR and 95% CI in the population of 6885 children who reported not living with both parents at the 11-year follow-up in the same two models. All analyses were made with the aid of SPSS 26.0 (IBM).

3 RESULTS

At the 11-year follow-up, 34 678 children in the 68 254 families with cohabiting parents who participated in the 6 months data collection were included in the population for this study (Figure 1). In an attrition analysis (Table S1), we found that non-participant mothers more often had a history of psychiatric care (7.7% vs 5.0% in participating mothers), more often were mothers of daughters (54.6% vs 47.8%), were slightly younger and less often had a university degree. In the study population, 79.9% were living with both parents, 7.2% in joint physical custody, 5.8% in a stepfamily and 6.9% with a lone parent. Comparisons of socio-demographic indicators with this attrition with the attrition for the complete cohort of 92 274 families showed similar patterns (Table S1).

Table 1 shows the selected register-based socioeconomic and psychiatric parental determinants, prior to the birth of the child, by family arrangement at the 11-year follow-up. Children still living with both parents more often had parents with higher incomes and a high educational level and less often a psychiatric disorder, compared with children living in a stepfamily or with a single parent. Children living in joint physical custody had a socioeconomic profile and level of parental psychiatric disorders in between children living with both parents and children living in a stepfamily or with a lone parent.

| With both | Joint physical custody | Stepfamily | Lone parent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 27 823 | N = 2510 | N = 2001 | N = 2344 | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Boys | 48.4 | 46.6 | 43.8 | 44.7 |

| Girls | 51.6 | 53.4 | 56.2 | 55.3 |

| Maternal age at birth of child | ||||

| 15-22 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 7.2 | 3.5 |

| 23-28 | 32.4 | 37.0 | 45.4 | 31.0 |

| 29-34 | 49.8 | 46.3 | 39.0 | 44.9 |

| 35+ | 16.6 | 13.4 | 8.4 | 20.6 |

| Disposable income before birth | ||||

| Quintile 1 | 14.8 | 18.7 | 26.0 | 22.9 |

| Quintile 2 | 18.9 | 19.3 | 23.4 | 22.8 |

| Quintile 3 | 20.7 | 19.7 | 21.6 | 20.8 |

| Quintile 4 | 22.5 | 21.3 | 17.1 | 18.9 |

| Quintile 5 | 23.1 | 21.3 | 12.0 | 14.6 |

| Maternal education before birth of child | ||||

| Primary | 4.3 | 4.6 | 9.4 | 9.3 |

| Secondary | 35.1 | 33.5 | 46.4 | 42.2 |

| 1-3 y post secondary | 43.9 | 43.6 | 35.6 | 38.5 |

| 4+ years post-secondary | 16.6 | 18.3 | 8.5 | 10.1 |

| Paternal education before birth of child | ||||

| Primary only | 8.9 | 8.6 | 21.2 | 18.2 |

| Secondary | 44.0 | 42.8 | 54.3 | 50.4 |

| 1-3 y post secondary | 28.7 | 30.1 | 17.7 | 20.7 |

| 4+ years post-secondary | 18.4 | 18.5 | 6.8 | 10.7 |

| Parental psychiatric disorder before birth of child | ||||

| Father | 3.7 | 5.5 | 11.0 | 11.8 |

| Mother | 4.5 | 6.5 | 9.6 | 8.9 |

In Table 2, the maternally reported family situation and maternal depression during infancy are presented by family arrangements at the 11-year follow-up. Mothers who remained cohabiting with the father at the 11-year follow-up, less often had reported having been depressed, having been burdened by the relation to the father and/or the economy in the 6 months interview compared with mothers who had separated. The early father-child relation, as assessed by the mother, was more often reported to have been problematic in families where children at age 11 years lived with a lone parent or in a stepfamily arrangement.

| With both | Joint physical custody | Stepfamily | Lone parent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 27 823 | N = 2510 | N = 2001 | N = 2344 | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Mother: At least two out of eight mental health items | ||||

| No | 85.8 | 75.5 | 70.8 | 66.9 |

| Yes | 14.2 | 24.5 | 29.2 | 33.1 |

| Mother burdened by relation to father | ||||

| No | 85.8 | 75.5 | 70.8 | 66.9 |

| Some or much | 14.2 | 15.5 | 17.6 | 19.8 |

| Mother burdened by economy | ||||

| No | 74.7 | 67.9 | 57.7 | 57.2 |

| Some or much | 25.3 | 32.1 | 42.3 | 42.8 |

| Mother-child relation problem | ||||

| No | 89.3 | 89.3 | 86.0 | 85.7 |

| Some or much | 10.7 | 10.7 | 14.0 | 14.3 |

| Father-child relation problem | ||||

| No | 96.4 | 93.2 | 88.5 | 89.1 |

| Some or much | 3.6 | 6.8 | 11.5 | 10.9 |

The logistic regression analysis of the predictors for parental separation is presented in Table 3. The fully adjusted model two showed that mothers being burdened by the relation to father was a relationship predictor of later parental separation (OR: 2.21, 95% CI: 2.04-2.39). Maternally reported problematic father-child relation was the second strongest relationship predictor (OR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.31-1.66). Severe paternal and maternal psychiatric disorders before the birth of the child also predicted parental separation, (OR: 2.09 95% CI: 1.88-2.11) and (OR: 1.43 95% CI: 1.27-1.59), respectively. Of the socioeconomic and demographic variables, young maternal age at the birth of the child strongly predicted parental separation; (OR: 2.48 95% CI: 2.08-2.97) for 17-22 years of age compared with 35+ years, as did low paternal and maternal education, (OR: 1.88 95% CI: 1.68-2.11) and (OR: 1.49 95% CI: 1.30-1.72), compared with a university education. Household income in quintiles predicted parental separation in a gradual pattern, with (OR: 1.54 95% CI: 1.40-1.69) for the lowest quintile compared with the highest.

| Model 1a | Model 2a | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Child gender | ||

| Girl vs boy | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | 1.09 (1.03-1.15) |

| Six months items | ||

| Mother: At least two out of eight mental health symptoms | 1.10 (1.02-1.18) | 1.09 (0.96-1.24) |

| Mother burdened by relation to father | 2.18 (2.02-2.35) | 2.21 (2.04-2.39) |

| Mother burdened by economy | 1.42 (1.33-1.52) | 1.26 (1.17-1.34) |

| Mother-Child relation problem | 1.10 (0.97-1.25) | 1.09 (0.96-1.24) |

| Father-Child relation problem | 1.60 (1.43-1.80) | 1.47 (1.31-1.66) |

| Parental psychiatric disorder before the birth of the child | ||

| Father | 2.09 (1.88-2.33) | |

| Mother | 1.43 (1.28-1.60) | |

| Socio-demographic variables before the birth of the child | ||

| Maternal age | ||

| 15-22 | 2.48 (2.08-2.97) | |

| 23-28 | 1.22 (1.12-1.33) | |

| 29-34 | 1.03 (0.95-1.12) | |

| 35+ | 1 | |

| Disposable income of household | ||

| Quintile 1 | 1.54 (1.40-1.69) | |

| Quintile 2 | 1.25 (1.14-1.37) | |

| Quintile 3 | 1.15 (1.05-1.26) | |

| Quintile 4 | 1.05 (0.96-1.15) | |

| Quintile 5 | 1 | |

| Maternal education | ||

| Primary only | 1.49 (1.30-1.72) | |

| Secondary | 1.18 (1.07-1.30) | |

| 1-3 post-secondary | 1.03 (0.95-1.12) | |

| 4+ post-secondary | 1 | |

| Paternal education | ||

| Primary only | 1.88 (1.68-2.11) | |

| Secondary | 1.39 (1.26-1.52) | |

| 1-3 post-secondary | 1.12 (1.03-1.25) | |

| 4+ post-secondary | 1 | |

- a Bold text indicates statistically significant predictors on the P < .05 level in the fully adjusted model.

Table 4 shows the results of the analysis of predictors for living arrangements, restricted to the 6885 children whose parents were not cohabiting at the 11-year follow-up, thus living in either joint physical custody, in a stepfamily or with a lone parent. Joint physical custody was less common than living in a stepfamily or with a lone parent if the mother was burdened by the relation to the father or the economy in the 6 months’ interview. If the father had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder before the birth of the child, the chance for joint physical custody was lower, (OR: 0.51 95% CI: 0.41-0.63). Parental educational levels and household income before the birth of the child predicted living in joint physical custody in a strong and graded manner. The lowest socioeconomic position before the birth of the child predicted a low chance of joint physical custody; low level of paternal education (OR: 0.33 95% CI: 0.26-0.41) and lowest quintile of household income (OR: 0.62 95% CI: 0.52-0.73) compared with high educational level and the highest income quintile.

| Model 1a | Model 2a | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Child gender | ||

| Girl vs boy | 0.91 (0.82-1.00) | 0.93 (0.83-1.02) |

| Six months items | ||

| Mother: At least two out of eight mental health symptoms | 1.03 (0.90-1.17) | 1.05 (0.91-1.18) |

| Mother burdened by relation to father | 0.87 (0.76-1.00) | 0.83 (0.72-0.95) |

| Mother burdened by economy | 0.76 (0.67-0.86) | 0.84 (0.74-0.96) |

| Mother-Child relation problem | 0.96 (0.77-1.21) | 0.96 (0.76-1.21) |

| Father-Child relation problem | 0.83 (0.69-1.02) | 0.94 (0.76-1.16) |

| Parental psychiatric disorder before the birth of the child | ||

| Father: psychiatric diagnosis | 0.86 (0.70-1.06) | |

| Mother: psychiatric diagnosis | 0.51 (0.41-0.63) | |

| Socio-demographic variables before the birth of the child | ||

| Maternal age | ||

| 15-22 | 1.23 (0.91-1.67) | |

| 23-28 | 1.28 (1.09-1.51) | |

| 29-34 | 1.21 (1.04-1.42 | |

| 35+ | 1 | |

| Disposable income of household | ||

| Quintile 1 | 0.62 (0.52-0.73) | |

| Quintile 2 | 0.69 (0.58-0.82) | |

| Quintile 3 | 0.73 (0.62-0.86) | |

| Quintile 4 | 0.87 (0.73-1.03) | |

| Quintile 5 | 1 | |

| Maternal education | ||

| Primary only | 0.45 (0.34-0.59) | |

| Secondary | 0.58 (0.49-0.69) | |

| 1-3 post-secondary | 0.88 (0.74-1.05) | |

| 4+ post-secondary | 1 | |

| Paternal education | ||

| Primary only | 0.33 (0.26-0.41) | |

| Secondary | 0.53 (0.44-0.62) | |

| 1-3 post-secondary | 0.88 (0.74-1.05) | |

| 4+ post-secondary | 1 | |

- a Bold text indicates statistically significant predictors on the P < .05 level in the fully adjusted model.

4 DISCUSSION

This study of 34 678 11-year-old children from the Danish Birth Cohort identified family relationships when the child was 6 months old, parental mental health before the birth and at child age 6 months as well as socioeconomic indicators before the birth of the child as predictors of parental separation before the age of 11 years. These indicators also predicted children's post-divorce living arrangements, with joint physical custody being more common if parents had a longer education, a higher income and were without a history of a severe psychiatric disorder.

Our results confirm previous studies with regards to the importance of social determinants for parental separation. Factors like low educational level, low income and young parental age seem to be robust predictors for parental separation, in Denmark in the 2000s as well as in multiple high-income countries in the previous decades.2, 3 Parental separation further enhances economic inequalities in children's living conditions by increasing the income differentials for families who had lower incomes even before the child was born.3 This study shows that a new factor has to be accounted for in the social context of parental separation with the establishment of joint physical custody as a common living arrangement for children after parental separation. Joint physical custody is clearly associated with a more favourable situation in the family with regards to income and parental education. To some extent, this is probably a consequence of the increased costs involved in providing two homes for the child.19 In joint physical custody, the child can also access the material resources of two households, which further enhances the inequality herewith for children after parental separation. In joint physical custody, the child has better prerequisites to maintain their bonds with the father, thus reducing an important negative consequence of parental separation.20 Considering the better mental health outcomes for children in joint physical custody compared with children living in a stepfamily or with a lone parent, joint physical custody potentially adds another layer to the social determinants of child health, by reducing the negative consequences of parental separation more in children from privileged social circumstances.

There are few previous studies in the literature on the consequences of different living arrangements for children that have adjusted the analysis for socioeconomic factors and family relationships prior to the separation.4 Hence, conclusions about such consequences based on these studies may have been biased by social confounding.

Norwegian researchers have shown that parents with joint physical custody rate their ability to communicate and agree on decisions regarding their children as better than parents of children in lone care.21 Our findings that problematic spousal relationships in infancy predict parental separation was somewhat expected, but is nonetheless important from a preventive perspective. Interventions during the transition to parenthood have been shown to improve communication between parents as well as the coparenting relationship, and thus how well parents coordinate their roles, communicate, agree and support each other.22 Such early interventions may be of general importance since these abilities predict children's health and wellbeing,22-24 but also specifically to prevent parental separation.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The longitudinal design in a large sample of children who experience parental separation during the course of the data collection, enabled by the large Danish National Birth Cohort, is the main strength of this study. The main limitation is the selective attrition of children with a low socioeconomic position and children who have experienced parental separation. This limitation if further emphasised by a previous study in the Danish Birth Cohort that showed that cohabitation with the father of the child in the study was associated with a higher response rate of the mother at the data collection at child age 11 years (cohabiting: 51.5% vs lone parent: 42.7%, P < .001).25 The combination of a selective attrition of separated parents and parents with low socioeconomic status, however, is what would be expected if the relation between the social determinants and parental separation was similar to the association found in this study. This socially graded attrition is thus more likely to lead to an underestimation than an overestimation of the true predictive effects of the socioeconomic indicators on parental separation. Hence, it seems unlikely that this association per se predicted whether the child in the cohort participated in the 11-year follow-up or not. The unexpected finding that being a girl was associated with parental separation, however, is possibly an artefact related to the selective attrition of boys, combined with the selective attrition of children having experienced parental separation. Another limitation is the lack of information about the age of the child when the parental separation occurred, which hindered an analysis in a person time-based framework.

5 CONCLUSION

Socioeconomic living conditions and family relationships in early childhood predict parental separation and living arrangements after parental separation in 11-year-old children. Studies of consequences of living arrangements after parental separation should account for family factors preceding the separation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.