Prevalence of epiretinal membranes in the ageing population using retinal colour images and SD-OCT: the Alienor Study

Abstract

Purpose

To analyse and compare the prevalence of epiretinal membranes (ERMs) obtained using either standard retinal colour images or spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) in a population-based setting of French elderly subjects.

Methods

Six hundred twenty-four subjects of the Alienor cohort aged 75 years or older underwent both colour fundus imaging and SD-OCT examinations. The ERMs were graded from retinal images and SD-OCT macular scans in a masked fashion. On SD-OCT images, the early ERMs, mature contractile ERMs without foveal modifications and mature contractile ERMs with foveal alterations were distinguished.

Results

610 (97.8%) subjects had gradable SD-OCT examinations, and 511 (81.9%) had gradable fundus images in at least one eye. According to colour photographs, 11.6% of participants had definite ERMs. From SD-OCT images, 52.8% of the subjects had early ERMs, 7.4% had mature ERMs without foveal involvement, and 9.7% had mature ERMs with foveal alterations. Regardless of the imaging method used, the ERMs were more often observed in pseudophakic eyes than in phakic eyes. Comparison of ERM assessment using fundus photographs versus SD-OCT images demonstrated that the specificity of retinal colour images was good (>89.3%), whereas the sensitivity remained low even though it increased with ERM severity on SD-OCT images.

Conclusions

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) examinations have high feasibility in this elderly population and are much more sensitive than standard colour images for ERM assessments, especially in the early stages of the disease. Our results further highlight the need to use SD-OCT instead of colour retinal photographs for the classification of ERMs in epidemiological studies.

Introduction

Epiretinal membranes (ERMs) are fibroblastic cell proliferations on the inner surface of the macula that may affect vision in elderly people (Wise 1975; Bu et al. 2014). Epiretinal membranes (ERMs) lead to a crinkled cellophane appearance of the macula that can be associated with abnormal vascular distortion, intraretinal cysts and/or a lamellar macular hole (Jaffe 1967; Massin et al. 2000; Witkin et al. 2006; Meuer et al. 2015). Epiretinal membranes (ERMs) are usually asymptomatic in the early stages (Klein et al. 1994; Mitchell et al 1997). Mature ERMs, conversely, may induce significant visual symptoms, such as metamorphopsia, micropsia and, occasionally, monocular diplopia due to mechanical distortions and tangential tractions on the retina, finally resulting in significant visual impairment (Bouwens et al. 2003; Fraser-Bell et al. 2004). Surgical removal of ERMs is the only available treatment. A residual loss of visual function, however, frequently occurs (Massin et al. 2000; Niwa et al. 2003), especially in advanced long-lasting ERM cases.

Previous population-based studies have analysed the ERM prevalence and risk factors across different populations, mainly in the United States and the Western Pacific region, while few data are available for the European continent. Most epidemiologic reports – even those recently conducted (Kim et al. 2017) – have relied solely on retinal photographs to identify ERMs (Xiao et al. 2017). In these studies, ERM prevalence has been reported to range between 1.02% (Zhu et al. 2012) and 28.9% (Ng et al. 2011). However, although mature ERMs can be detected easily on fundus retinal images, early ERMs can be under- or misdiagnosed. Therefore, the current gold standard for ERM assessment and, more widely, vitreoretinal interface analysis in routine clinical practice has now become optical coherence tomography (OCT), which allows early ERM detection and monitoring. The first epidemiological study that analysed ERM prevalence using time-domain OCT in a rural Chinese population reported an ERM prevalence rate of 20.6% after 80 years (Duan et al. 2009). Since then, spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) has drastically improved the detailed analysis of retinal morphology and allowed the detection rate of ERMs to increase (Ko et al. 2005). Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scans not only show the consequences of ERMs on retinal anatomical structures but also further allow visual prognostic factors to be evaluated, which can guide ERM therapeutic management (Suh et al. 2009; Inoue et al. 2010; Kinoshita et al. 2011; Okamato et al. 2015; Stevenson et al. 2016; Govetto et al. 2017). Recently, the Beaver Dam Eye Study (BDES) used SD-OCT to evaluate ERM prevalence in a North American population aged 63–102 years and reported the highest ERM prevalence ever recorded, which was 34.1% (Meuer et al. 2015). For the risk factors, ERMs were found to be associated with age and ethnicity (Klein et al. 1994; Mitchell et al 1997; Fraser-bell et al. 2003; Fraser-Bell et al. 2004; McCarty et al. 2005; You et al. 2008; Kawasaki et al. 2008; Ng et al. 2011; Aung et al. 2013; Cheung et al. 2017; Xiao et al. 2017). Other factors, such as a history of cataract surgery, diabetes, vein occlusion, uveitis, ocular surgery or trauma, were also identified as responsible for ‘secondary ERM’ (Appiah et al., 1988; Klein et al. 1994; Mitchell et al. 1997; Fraser-bell et al. 2003; Fraser-Bell et al. 2004; McCarty et al. 2005; You et al. 2008; Ng et al. 2011).

The purpose of the present study was to estimate the prevalence of ERMs in a European–French elderly population using fundus colour images and SD-OCT scans and to compare the sensitivity and specificity of the two techniques for an epidemiological approach to the disease.

Subjects and methods

The Alienor (Antioxydants, Lipides Essentiels, Nutrition et maladies OculaiRes) Study is a population-based prospective study that was developed to assess the associations of age-related eye diseases (age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, cataract, dry eye syndrome) with nutritional factors (in particular antioxidants, macular pigment and fatty acids). It also takes into account other major determinants of eye diseases, including gene polymorphisms, lifestyles and vascular factors (Delcourt et al. 2010).

Study population

Subjects in the Alienor Study were recruited from the Three Cities (3C) Study, an ongoing population-based study on the vascular risk factors for dementia (3C Study Group, 2003). The 3C Study has included 9294 subjects aged 65 years or more from three French cities (Bordeaux, Dijon and Montpellier), among whom 2104 were recruited from Bordeaux. Subjects were contacted individually from the electoral records. They were initially recruited in 1999–2001 and followed up approximately every 2 years since. The Alienor Study consists of an eye examination administered to all participants after the third follow-up (2006–2008) in the 3C cohort of Bordeaux, and the aim of the study was to evaluate age-related eye diseases (in particular age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, cataract and dry eye syndrome). Among the 1450 participants who were re-examined between October 2006 and May 2008, 963 participated in the first eye examination of the Alienor Study. Detailed characteristics of the participants and nonparticipants have been published elsewhere (Delcourt et al. 2010). The results presented in the present paper are based on the data from the fourth follow-up in the 3C cohort (2009–2010), corresponding to the second follow-up of the Alienor Study, during which an SD-OCT examination of the macula and of the optic nerve was included in the eye examination. Among the 904 Alienor Study participants still alive, 624 (69%) participated in this eye examination.

The study design was approved by the Ethical Committee of Bordeaux in May 2006. All participants gave written consent to participate in the study which was carried out in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Eye examination

All eye examinations were performed in the Department of Ophthalmology of Bordeaux University Hospital and included a refraction assessment by an autorefractometer (Speedy-K, Luneau, Prunay le Gillon, France), best-corrected visual acuity assessment (Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) charts), slit lamp examination, 45° retinal colour photographs captured using a nonmydriatic retinograph (TRC NW6S; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) and SD-OCT imaging performed with Spectralis® OCT (Spectralis®, Software Version 5.4.7.0; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Cataract extraction was defined as the absence of the natural crystalline lens in the slit lamp examination. Nonmydriatic colour retinal images were taken in a dark room by a trained technician. A minimum of two 45-degree field retinal photographs (one centred on the macula and one centred on the optic disc) were taken in each eye. All SD-OCT assessments were performed by the same experienced technician without pupil dilation. For macular cube acquisition, the conditions used for acquisition were as follows: resolution mode, high speed; scan angle, 20°; size X, 1024 pixels (5.7 mm); size Z, 496 pixels (1.9 mm); scaling X, 5.54 µm/pixel; scaling Z, 3.87 µm/pixel; number of B-scans, 19; pattern size, 20 × 15°; and distance between B-scans, 236 µm. Standard horizontal and vertical B-scan images centred on the fovea were also taken.

ERM grading from retinal photographs

The presence of ERM was graded from colour retinal photographs centred on the macula. Epiretinal membranes (ERMs) were defined as a modified macular appearance consisting either in a subtle cellophane aspect or in a substantial preretinal macular fibrosis, associated or not with traction lines (corresponding to retinal folds) or vascular stretching. Retinal photographs were interpreted in duplicate by two specially trained technicians. In some cases, precise identification of the lesion required contrast and/or colour-balance adjustments. If the grader determined that the probability of the presence of a lesion was greater than 90%, then the lesion was considered present. If the probability was between 50% and 90%, the lesion was considered questionable. If the probability was less than 50%, the lesion was considered absent. Inconsistencies between the two graders were resolved by a senior grader (MND, MBR, CD, JFK).

ERM grading from SD-OCT images

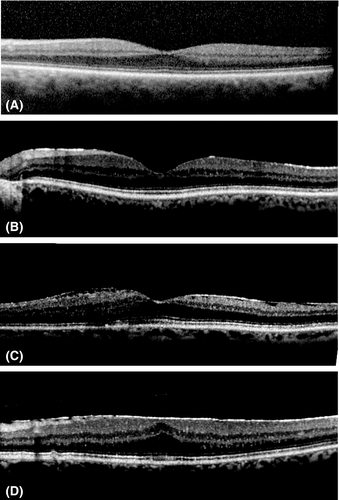

ERM grading after the SD-OCT examination was performed using all available SD-OCT images. On OCT scans, ERMs appear as a continuous hyperreflectivity of the inner surface of the retina, which can be associated with rippling of the retinal surface and can involve the fovea. On macular cube, mature ERMs often result in a thickening of the central foveal region. In the absence of a standardized OCT-based classification of ERMs applicable for epidemiological purposes, the ERMs were graded in our study from SD-OCT scans as follows: (i) stage 0: absence of continuous hyperreflective signal at the inner retinal surface, (ii) stage 1 or continuous hyperreflectivity: presence of a continuous hyperreflective signal at the inner retinal surface on at least three consecutive sections of the macular cube (to limit confusion with posterior hyaloid reflectivity), (iii) stage 2 or mature ERM without foveal involvement: stage 1 associated with retinal folds but without alterations of the foveal depression and, finally, (iv) stage 3 or mature ERM with foveal involvement: stage 2 associated with foveal depression alterations (Fig. 1). All SD-OCT images were interpreted by the same trained ophthalmologist (PL) who was blinded to the retinal photograph grades and all other clinical data. The reliability of OCT interpretations was checked by measuring the interrater agreement coefficient between the grader (PL) and a senior retina specialist (MND). The kappa coefficient was 0.91 [0.82–1.00]. The central foveal thickness (CFT) was measured automatically using the software associated with the SD-OCT (Heidelberg Eye Explorer software, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). The CFT was considered to have increased when it was larger than 350 μm.

Statistical analyses

The demographic data (Table 1) are presented using common statistics, that is the frequency and percentage (%) for categorical data and the means and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Frequencies were compared between groups using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, and means were compared using Student’s t-test. p-Values adjusted for age and sex were obtained using logistic regression models. Epiretinal membrane (ERM) prevalence according to the age and sex per subject (Table 2) and to the lens status per eye (Table 3) was presented as N (%), and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using the normal approximation if the assumptions were respected or the exact binomial distribution if not. The frequencies were compared between the lens status groups using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. For the evaluation of the sensitivity and the specificity of retinal photographs in assessing ERMs (Table 4), each eye was studied independently. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated using the SD-OCT grades as the reference, and the estimate rates were accompanied by 95% CIs calculated using the normal approximation if the assumptions were respected or the exact binomial distribution if not. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

| Characteristics | Included participants (N = 610) | Non-included participants (N = 353) | p-Value | Sex- and age-adjusted p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 79.4 ± 4.2 | 81.4 ± 4.5 | <0.0001 | |

| Males | 229 (37.5) | 138 (39.1) | 0.63 | |

| Education level | N = 610 | N = 352 | 0.0025 | 0.0076 |

| No education or primary | 159 (26.1) | 126 (35.8) | ||

| School only | 163 (26.7) | 94 (26.7) | ||

| Secondary school or higher | 288 (47.2) | 132 (27.5) | ||

| Monthly income, euros | N = 575 | N = 329 | 0.05 | 0.17 |

| <1500 | 212 (36.9) | 143 (43.5) | ||

| ≥1500 | 363 (63.1) | 186 (56.5) | ||

| Smoking | N = 605 | N = 346 | 0.79 | 0.86 |

| Never | 391 (64.6) | 223 (64.5) | ||

| <20 pack-year | 110 (18.2) | 68 (19.6) | ||

| ≥20 pack-year | 104 (17.2) | 55 (15.9) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | N = 599 | N = 340 | 0.58 | 0.91 |

| 26.0 ± 4.0 | 25.8 ± 4.2 | |||

| Diabetes | N = 608 | N = 351 | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| 68 (11.2) | 41 (11.7) | |||

| Hypertension | N = 609 | N = 348 | 0.23 | 0.37 |

| 494 (81.1) | 293 (84.2) | |||

| Pseudophakia* | N = 608 | N = 350 | 0.0108 | 0.69 |

| 254 (41.8) | 176 (50.3) | |||

| Age-related macular degeneration* | N = 564 | N = 315 | 0.0252 | 0.25 |

| No | 381(67.6) | 200 (63.5) | ||

| Early | 162 (28.7) | 90 (28.6) | ||

| Late | 21 (3.7) | 25 (7.9) | ||

| Retinal vein occlusion* | N = 565 | N = 313 | 0.77 | 0.89 |

| 6 (1.1) | 4 (1.3) | |||

| Retinopathy* | N = 564 | N = 311 | 0.35 | 0.52 |

| 44 (7.8) | 30 (9.6) |

- Data are presented as N (%) or mean ± SD. The values in bold indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05).

- * At least in one eye.

| Sex | Age (years) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | 75–79 | 80–85 | >85 | ||

| Retinal colour images | ||||||

| N | 186 | 325 | 203 | 189 | 119 | 511 |

| Questionable |

10 (5.4) [2.6–9.7]* |

25 (7.7) [4.8–10.6] |

12 (5.9) [2.7–9.2] |

15 (7.9) [4.1–11.8] |

8 (6.7) [3.0–12.8]* |

35 (6.9) [4.7–9.0] |

| Definite ERM |

33 (17.7) [12.3–23.2] |

26 (8.0) [5.1–11.0] |

23 (11.3) [7.0–15.7] |

22 (11.6) [7.1–16.2] |

14 (11.8) [6.0–17.6] |

59 (11.6) [8.8–14.3] |

| SD-OCT | ||||||

| N | 229 | 381 | 233 | 225 | 152 | 610 |

| Stage 1 |

119 (52.0) [45.5–58.4] |

203 (53.3) [48.3–58.3] |

105 (45.1) [38.7–51.5] |

122 (54.2) [47.7–60.7] |

95 (62.5) [54.8–70.2] |

322 (52.8) [48.8–56.8] |

| Stage 2 |

19 (8.3) [4.7–11.9] |

26 (6.8) [4.3–9.4] |

18 (7.7) [4.3–11.2] |

16 (7.1) [3.8–10.5] |

11 (7.2) [3.7–12.6]* |

45 (7.4) [5.3–9.5] |

| Stage 3 |

27 (11.8) [7.6–16.0] |

32 (8.4) [5.6–11.2] |

27 (11.6) [7.5–15.7] |

23 (10.2) [6.3–14.2] |

9 (5.9) [2.7–10.9]* |

59 (9.7) [7.3–12.0] |

- Data are presented as N (%), [95 % confidence interval].

- * Exact binomial 95% confidence interval.

| Phakic | Pseudophakic | p-Value | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photographs | ||||

| N | 423 | 451 | 874 | |

| Questionable |

14 (3.3) [1.6–5.0]* |

34 (7.5) [5.1–10.0] |

0.0061 |

48 (5.5) [4.1–7.2]* |

| Definite ERM |

17 (4.0) [2.4–6.4]* |

50 (11.1) [8.2–14.0] |

<0.001 |

67 (7.7) [5.9–9.4] |

| SD-OCT | ||||

| N | 616 | 571 | 1187 | |

| Stage 1 |

247 (40.1) [36.2–44.0] |

291 (51.0) [46.9–55.1] |

0.0002 |

538 (45.3) [42.5–48.2] |

| Stage 2 |

30 (4.9) [3.3–6.9]* |

32 (5.6) [3.7–7.5] |

0.57 |

62 (5.2) [4.0–6.5] |

| Stage 3 |

30 (4.9) [3.3–6.9]* |

37 (6.5) [4.5–8.5] |

0.23 |

67 (5.6) [4.3–7.0] |

- Data are presented as N (%), [95% confidence interval].

- * Exact binomial 95% confidence interval.

| SD-OCT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | |

| All (n = 886) | |||

| Sensitivity |

38/396 (9.6) [6.9–12.9] |

8/47 (17.0) [7.7–30.8] |

21/47 (44.7) [30.2–59.9] |

| Specificity |

460/490 (93.9) [91.4–95.8] |

779/839 (92.9) [90.9–94.5] |

792/839 (94.4) [92.6–95.9] |

| Pseudophakic (n = 449) | |||

| Sensitivity |

31/225 (13.8) [9.6–19.0] |

5/29 (17.2) [5.9–35.8] |

13/28 (46.4) [27.5–66.1] |

| Specificity |

205/224 (91.5) [87.1–94.8] |

375/420 (89.3) [85.9–92.1] |

384/421 (91.2) [88.1–93.7] |

| Phakic (n = 420) | |||

| Sensitivity |

7/164 (4.3) [1.7–8.6] |

3/18 (14.3) [3.1–36.3] |

7/18 (38.9) [17.3–64.3] |

| Specificity |

246/256 (96.1) [92.9–98.1] |

388/402 (96.5) [94.2–98.1] |

392/402 (97.5) [95.5–98.8] |

- Data are presented as N/participants (%), [95% confidence interval].

Results

Among the 624 participants, 610 (97.8%) had a gradable SD-OCT and 511 (81.9%) had gradable retinal photographs in at least one eye. As shown in Table 1, the participants (n = 610) were similar to the nonparticipants (n = 353) regarding most characteristics (sex, monthly income, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, blood hypertension), but they were younger than the nonparticipants (p < 0.0001) and had a higher education level (p = 0.0025, and p = 0.0076 after adjustment for age and sex). Before the adjustment, the nonparticipants were more often pseudophakic and affected by AMD than the participants, but these differences were no longer significant after the adjustment for age and sex.

As shown in Table 2, using the retinal photograph grading, 59 subjects (11.6%) were identified as presenting definite ERMs and 35 subjects (6.9%) had questionable ERMs. Definite ERMs were statistically more frequent in men (17.7%) than in women (8.0%, p = 0.009) but were not associated with the age groups (p = 0.99). On the other hand, analyses of the SD-OCT images showed that 322 subjects (52.8%) had continuous hyperreflectivity at the inner retinal surface on at least three consecutive sections of the macular cube (stage 1 ERMs), 45 subjects (7.4%) had stage 2 ERMs (mature ERMs without foveal involvement) and 59 (9.7%) had stage 3 ERMs (mature ERMs with foveal involvement, Table 2). The ERM stages were similarly distributed in men and women (p = 0.75, p = 0.50 and p = 0.17 for stages 1, 2 and 3, respectively). Stage 3 ERMs were less frequent in the oldest group (5.9%), that is in subjects aged 85 years or older, than in the groups aged 75–79 (11.6%) or 80-85 years (10.2%) (p = 0.0032), while the prevalence of stages 1 and 2 was not significantly different across age groups (p = 0.97 and p = 0.17, respectively).

Lens status is known to possibly alter and sometimes bias the definition of retinal imaging, and lens removal is known to be associated with an increased ERM prevalence. We further analysed the ERMs using either retinal colour photographs or SD-OCT in phakic and pseudophakic eyes. As shown in Table 3, using the retinal photographs, questionable and definite ERMs were more often observed in pseudophakic eyes (7.5% and 11.1%, respectively) than in phakic eyes [3.3% (p = 0.0061) and 4.0% (p < 0.001), respectively]. Using the SD-OCT images, stage 1 ERMs were also more often detected in pseudophakic eyes (51.0%) than in phakic eyes (40.1%; p = 0.0002), while stages 2 and 3 were detected in pseudophakic eyes as frequently as they were detected in phakic eyes (p = 0.57 and p = 0.23, respectively).

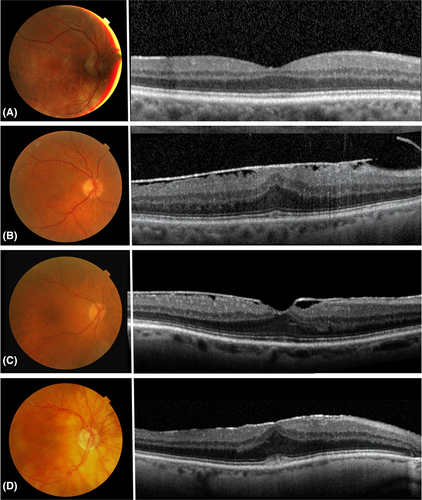

As shown in Table 4, the specificity of the retinal colour images was high for all SD-OCT stages of ERMs (>89.3%). However, the sensitivity of fundus images as compared to SD-OCT remained low, even though it increased with the severity of the stage of the membrane on the SD-OCT results (9.6% for stage 1, 17.0% for stage 2 and 44.7% for stage 3). For comparison, among the 68 ERMs diagnosed on fundus images, only one case was not identified as an ERM on SD-OCT sections. This corresponds to a sensitivity of 98.5% for SD-OCT as compared to retinal colour photographs. Lens status was found to influence the sensitivity of the retinal photographs in the early stages of ERMs (stage 1): sensitivity was 4.3% in phakic eyes vs. 13.8% in pseudophakic eyes (Table 4). Lens status, however, was not found to affect the sensitivity for stages 2 and 3 (Table 4). Variations in the classification of the ERMs from the retinal photographs as compared to the SD-OCT scans are illustrated in Fig. 2. Figure 2A and B shows two concordant cases of ERMs visualized both on the fundus image and on the SD-OCT scans. Conversely, Fig. 2C and D does not show any features of ERMs contrasting with the presence of stage 3 mature ERMs on the SD-OCT scans.

Finally, the mean CFT was evaluated for each of the stages in the SD-OCT classification and was shown to remain within normal ranges for ERM stages 0, 1 and 2: 273.37 μm (with a standard deviation (SD) of ± 29.91 µm), 274.66 μm (SD, ±27.26 µm) and 291.08 μm (SD, ±35.70 µm), respectively. Unsurprisingly, the mean CFT increased significantly in the stage 3 ERM group (358.62 μm; SD, ±65.17 µm) which is characterized by foveal involvement (p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this population-based study of French elderly subjects, the prevalence of ERMs detected in retinal photographs (11.6%) was in line with the findings from other studies in Caucasian elderly participants, such as the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (13.6%, participants aged 70 years old or older) (Aung et al. 2013), the Visual Impairment Project (11.3%, subjects aged 80 years or older) (McCarty et al. 2005), and the Blue Mountains Study (9.3%, subjects aged 80 years or older) (Mitchell et al. 1997). The results have been more inconsistent in other ethnic groups. In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) study, the prevalence was estimated to be 39.2% for participants aged over 75 years (Ng et al. 2011). Similarly high rates were found in the Singapore Indian Eye Study (27.7% in subjects aged between 70 and 80 years) (Koh et al. 2012) and the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (22.5% in subjects aged ≥80 and 35.7% in subjects aged 70–79) (Fraser-Bell et al. 2004). Conversely, ERM prevalence was lower in the Hisayama Study (4.7% in subjects aged ≥80 years) (Miyazaki et al. 2003) and in the Funagata Study (9.8%, subjects aged 75 years or above) (Kawasaki et al. 2009) in Japan, and the Beixinjing Blocks Shanghai Study in China (1.2% in subjects aged 70–79 years) (Zhu et al. 2012). The discrepancies in the prevalence rates may be due to true geographical and/or ethnic differences in the studied populations, but may additionally result – as recently pointed out in a meta-analysis (Xiao et al. 2017) – from differences in the imaging methods used (mydriatic versus nonmydriatic, stereoscopic versus nonstereoscopic, film versus digital) and the protocols used for ERM grading. The lack of standardized criteria, especially for evaluating early signs of ERMs on fundus colour images, is indeed a main issue (Xiao et al. 2017), and subtle macular modifications are clearly underestimated. Hence, in routine clinical practice, OCT has become the gold standard for vitreoretinal interface analysis and ERM assessment for years. Its use in epidemiologic studies therefore appears to be crucial but has been restricted to only three reports (Duan et al. 2009; Ye et al. 2015; Meuer et al. 2015). In these studies, ERMs were defined by the presence of a hyperreflective signal at the inner surface of the retina with evidence of contractility (Ye et al. 2015; Meuer et al. 2015), which may theoretically correspond to stages 2 and 3 in our classification system, depending on the presence or absence of foveal alterations (mature ERMs). In our population, the prevalence of mature ERMs (cumulated stages 2 and 3) was 17.05%, which is in line with the findings of the Handan Eye Study (using TD-OCT) and the Jiangning Eye Study (using SD-OCT), which reported a prevalence of 20.6% and 15.8% in subjects aged 80 or older, respectively (Duan et al. 2009; Ye et al. 2015). The prevalence rate in BDES, however, was much higher, at 53.2% after 85 years (Meuer et al. 2015). However, if we consider the ERMs that were defined as either early (stage 1) or mature (stages 2 and 3), the prevalence rate in our population is 69.84% (stages 1, 2 and 3 altogether), which appears to be rather consistent with the BDES findings. These discrepancies from one study to another highlight the need for a validated OCT classification of ERMs for epidemiologic purposes. The ERM grades determined with the classification system we used (Fig. 1) yielded very reproducible results and had excellent intergrader agreement (kappa = 0.91 [0.82–1.00]. However, although stages 0, 2 and 3 appear rather consensual, stage 1 – defined as a continuous hyperreflectivity present on at least three consecutive B-scan sections of the cube and considered as the early stage of ERM – could be more questionable. One may wonder whether this continuous hyperreflective signal truly represents early ERMs or is more likely due to posterior hyaloid reflection. In previous epidemiological studies, ERMs were arbitrarily categorized from fundus image findings into three groups: absence of ERM or presence of a ‘cellophane macular reflex’ (CMF) or presence of a ‘premacular fibrosis’ (PMF). In our cohort, CMF and PMF were found to be associated with the three different macular OCT profiles and as a substantial proportion of CMF and PMF were graded as stage 1 on SD-OCT (56.7%, Table 4), we feel that this category cannot be left out. It seems reasonable to conceive that before any regions with fibroblastic cell proliferation can exhibit any mechanical distortions or tangential tractions at the retinal surface, they must first develop. Continuous hyperreflective signals can therefore be considered as the early clinical signs of ERMs, and by choosing to only retain hyperreflective signals that were continuous (not only dots) and present on at least three consecutive scans separated by a 240-µm interval, we were able to avoid most of hyperreflectivities due to the posterior vitreous cortex.

Regarding the risk factors, ERMs are known to be associated with increasing age (Klein et al. 1994; Mitchell et al 1997; Fraser-bell et al. 2003; Miyazaki et al. 2003; Fraser-Bell et al. 2004; McCarty et al. 2005; You et al. 2008; Kawasaki et al. 2008; Kawasaki et al. 2009; Duan et al. 2009; Ng et al. 2011; Koh et al. 2012; Aung et al. 2013; Ye et al. 2015; Cheung et al. 2017; Xiao et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2017). In our population, however, we did not observe major differences across the three age groups using either retinal photographs or SD-OCT (at least for ERM stages 1 and 2). This result might be due to the mean advanced age of our participants (79.4 ± 4.2 years) and the closeness of the three age groups selected, that is 75–79, 80–85 and >85 years. Indeed, according to three previous epidemiological reports, ERMs peak at approximately 60–69 years (Fraser-Bell et al. 2003; Bae et al. 2017) or 70–79 years (Yang et al. 2018) and decline thereafter. One single difference was observed in our cohort for ERM stage 3 on SD-OCT, as it was found to be less frequent in the oldest group than in the two younger groups (p = 0.0032).

The influence of sex on ERM occurrence has been debated. Most prevalence and incidence surveys have not detected any associations with sex (Fraser-Bell et al. 2003; Fraser-Bell et al. 2004; Duan et al. 2009; Bae et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2018). In some reports, however, women were found to be more likely than men to develop ERMs (Mitchell et al. 1997; Kawasaki et al. 2008; Ye et al. 2015). In our cohort, although definite ERMs according to retinal photographs were statistically more frequent in men than in women (p = 0.009), the three ERM stages graded according to the SD-OCT images were similarly distributed between the two sexes (p = 0.75, p = 0.50 and p = 0.17 for stages 1, 2 and 3, respectively), which is in line with the findings in most of the above cited studies.

Pseudophakia has constantly been associated with a higher ERM prevalence (Appiah & Hirose 1988; Klein et al. 1994; Mitchell et al. 1997; Fraser-bell et al. 2003; Fraser-Bell et al. 2004; McCarty et al. 2005; You et al. 2008; Ng et al. 2011; Cheung et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2017). Such a finding can result from two nonexclusive factors. First, ERM assessment results, regardless the retinal imaging tool used, can be affected by the lens opacity in phakic eyes, even in dilated eyes (Scanlon et al. 2005), especially in patients over 75 years and those with central/nuclear cataracts. It seems, however, that OCT is far less affected by lens opacity than retinal colour images (Kowallick et al. 2018). Second, surgical removal of the lens itself has been proposed to be responsible for an increase in the ERM incidence, mainly due to secondary posterior vitreous detachment occurring in the weeks following surgery (Jahn et al. 2001; Ivastinovic et al. 2012; Fong et al. 2013). Comparison of ERM assessment in our cohort using the two imaging techniques according to the lens status was therefore interesting. While the specificity of retinal colour images was good with respect to the SD-OCT findings (>89.3%), their sensitivity remained low, especially for early ERMs and in phakic eyes (Table 4). Epiretinal membranes (ERMs) indeed appeared to occur more frequently in pseudophakic eyes when they were diagnosed using retinal colour photographs (p = 0.006 and p < 0.001 for questionable and definite ERMs, respectively, Table 3). By contrast, mature ERMs (stages 2 and 3) were found as frequently in phakic eyes as in pseudophakic eyes when they were diagnosed using SD-OCT (Table 3), confirming that retinal photographs are more affected by lens opacity than SD-OCT images. Notably, however, early ERMs (stage 1) were found more frequently with SD-OCT in pseudophakic eyes than in phakic eyes (p = 0.0002). This observation may be explained by the role of cataract surgery in ERM genesis, as discussed above (Jahn et al. 2001; Ivastinovic et al. 2012; Fong et al. 2013).

Another advantage of using SD-OCT to assess ERMs is that precise foveal alterations associated with ERMs can be detected and used to differentiate stages 2 and 3 on OCT B-scans. Hence, we were able in a population of elderly subjects to demonstrate an increase in central foveal thickness according to the stages of ERM severity (p < 0.001).

Nevertheless, our study has some limitations. First, only 610 (67.5%) of the 904 alive Alienor subjects were included in the present study and they were of advanced age (79.4 ± 4.2 years; Table 1). Second, the participants included in our study tended to be younger, have a higher education level and have a better visual acuity than nonparticipants (and the general population), thereby limiting the representativeness of our study population as previously discussed (Delcourt et al. 2010). However, for most parameters (i.e. sex, monthly income, smoking status, BMI, diabetes, blood hypertension) the individuals included in the Alienor Study were not different from those who did not participate in the study (Delcourt et al. 2010).

In conclusion, SD-OCT examinations demonstrated high feasibility in the elderly population in our study (97.8% of participants had gradable images) and was confirmed to be much more sensitive in ERM detection than standard 45° retinal colour photographs, especially for ERMs in the early stages. Early ERMs were detected on OCT B-scans for 52.8% participants, mature ERMs (stages 2 and 3) were detected in 17.05% of the participants, and 9.7% participants exhibited macular alterations and an increase in foveal thickness (stage 3). Prospective epidemiologic studies with follow-up SD-OCT data should be conducted to confirm our results and further analyse the evolution of ERMs over time.