Road Corridors as Real Estate Frontiers: The New Urban Geographies of Rentier Capitalism in Africa

Abstract

enThis paper draws on research on infrastructure-led development and urbanisation in Nairobi to explore the new urban geographies of rentier capitalism in Africa. Under the banner of Kenya's Vision 2030 national development strategy, Nairobi's agrarian hinterlands have been transformed by major road building projects. These initiatives have catalysed a peri-urban property boom characterised by the conversion of agricultural and ranching land into urban real estate and the verticalisation of road corridors. The paper identifies four processes of land transformation driving this real estate market expansion: commodification; speculation; autoconstruction; and assetisation. Adopting a multi-scalar conjunctural approach, it argues that rentier capitalism in this context is spatialised through the dramatic extension of real estate frontiers along the route of peri-urban road corridors. Development along these corridors assumes a “grey” character that defies conventional formal–informal distinctions, enabling the extraction of large rentier profits and encouraging the further proliferation of frontier spaces.

Abstract

swMakala haya yanatokana na utafiti kuhusu maendeleo ya miundombinu na ukuaji wa miji wa Nairobi ili kuchunguza jiografia mpya za miji wa ubepari wa mwenyeji ulioko Afrika. Chini ya azma ya maono ya Kenya ya mkakati wa Maendeleo ya Taifa ya Kenya 2030, mashamba ya Nairobi yaliyozunguka miji yamegeuzwa na miradi mikubwa ya ujenzi wa barabara. Miradi hii imechochea kuwepo kwa ongezeko la mali isiyohamishika kwenye maeneo ya pembezoni mwa miji, ikiwa ni pamoja na kubadilisha ardhi ya kilimo na malisho kuwa mali isiyohamishika ya miji na kulundikana kwa maeneo ya barabara. Makala haya yanabainisha michakato aina nne ya mabadiliko ya ardhi unaochangia ongezeko la soko la mali isiyohamishika: ubadilishaji bidhaa, ubatilishaji, ujenzi wa kibinafsi, na umilikishaji. Yanadai kwamba ubepari wa mwenyeji katika muktadha huu unatekelezwa kupitia kufungua kwa ukanda wa mipaka ya mali isiyohamishika katika njia ya barabara za pembezoni mwa miji. Maendeleo katika maeneo haya yana mwelekeo wenye kukiuka kinachoonekana kama kawaida cha rasmi na kisicho rasmi, na kuruhusu kufaidika kwa faida kubwa ya mwenye mjengo za ubepari na kuchangia kuendelea kupanuliwa kwa maeneo ya mpaka.

Introduction

Debates about 21st century capitalism have identified the increasing significance of rent, rentiers, and rentiership as perhaps the defining feature of contemporary accumulation dynamics. The current tendency for economic activity to revolve around the control of scarce rent-generating assets has been captured in the concept of “rentier capitalism”, popularised by Christophers’ (2020) influential book of the same name. Critical political economy research on rentier capitalism has documented the growing hegemony of rentier dynamics across diverse case studies, from the proliferation of digital platforms to the globalisation of supply chains (Arboleda and Purcell 2021; Birch and Ward 2023; Sadowski 2020). This shift has been underpinned by processes of “assetisation”, defined by Birch and Ward (2024:20) as “the transformation of an ever-growing range of things into assets from which to extract value”. Within the field of urban geography, there is a long tradition of critical research that views the social relations of land rent as central to capitalist urban development (Haila 2015; Harvey 2006; Ward and Aalbers 2016). Recent scholarship has examined how the rentier practices of diverse actors operating at multiple scales are shaping postcolonial urban transformations, with a particular focus on Asian cities (Cowan 2022; Desai and Loftus 2013; Leitner and Sheppard 2020; Pati 2022). Although there is emerging interest in the dynamics of rentier capitalism in Africa (Bierschenk and Muñoz 2021; Donovan and Park 2022), the urban geographical dimensions of this phenomenon remain underexplored.

In order to better understand the socio-spatiality of capitalism in Africa (Ouma 2017), this paper draws on the case of Nairobi to explore the new urban geographies of rentier capitalism on the continent. Kenya's capital is an ideal case study as the vast majority (86%) of households live in rental accommodation (Mwau et al. 2020). Private landlordism initially emerged in colonial Nairobi due to racial segregation policies that treated Africans as a temporary labour force to be contained within designated locations in the east of the city. The failure of the colonial state to provide sufficient housing for migrant workers led to the formation of an African landlord class in these settlements (White 1990). Following independence in 1963, restrictions on rural–urban migration were abolished and Nairobi's population grew rapidly. Kenyans acquired further land in the city through cooperatives and site-and-service schemes, and property owners responded to the growing demand for housing by investing in rental accommodation. As corruption became embedded in 1980s Kenya, multistorey tenements proliferated in defiance of planning and building regulations. High-rise private rental housing has subsequently come to dominate the production of space in the city (Huchzermeyer 2011).

While much tenement development in Nairobi has occurred through the densification of established settlements in the city, peri-urbanisation processes are increasingly opening up extra-metropolitan territories to urban rentiership. Under its Vision 2030 national development strategy, the Government of Kenya has pursued what Schindler and Kanai (2021) term an “infrastructure-led development” approach in which investment in large-scale connective infrastructure is prioritised as the key to social and economic modernisation. In Africa, national governments, multilateral institutions, and foreign donors have pursued infrastructure-led development in order to address an “infrastructure gap” that is inhibiting regional economic development (Goodfellow 2020). The outcome has been the proliferation of infrastructural “corridor” projects that seek to enhance the integration and competitiveness of African regions within the global economy (Enns and Bersaglio 2020; Gillespie and Schindler 2022; Wiig and Silver 2019). Since launching Vision 2030 in 2008, the Kenyan government has collaborated with international funders on several major road building projects on the edges of Nairobi. These initiatives have catalysed a peri-urban property boom characterised by the conversion of agricultural and ranching land into urban real estate and the emergence of dense neighbourhoods dominated by high-rise rental housing along the route of road corridors.

This paper examines the relationship between infrastructure-led development and urbanisation in Nairobi to understand the urban geographical dimensions of rentier capitalism in Africa. In the process, it identifies four processes of land transformation driving real estate market expansion: commodification; speculation; autoconstruction; and assetisation. Adopting a multi-scalar conjunctural approach to analyse the articulation of the general and particular, the paper argues that rentier capitalism in this context is spatialised through the dramatic extension of “real estate frontiers” (Gillespie 2020) along the route of peri-urban road corridors. Development along these corridors assumes a “grey” character (Smith 2020) in which state actors collude with speculators and facilitate regulatory bypassing by developers. This grey development enables the extraction of large rentier profits by powerful actors, encouraging the further proliferation of frontier spaces. The paper begins by reviewing literatures that provide insights into the urban geographical dimensions of rentier capitalism. It then examines the relationship between infrastructure-led development and urbanisation in Nairobi. Next, it identifies four distinct but related processes of land transformation that are driving the extension of real estate frontiers in this context. The paper concludes by reflecting on the importance of further research for understanding and responding to the geographical expansion of rentier capitalism.

Urban Geography and Rentier Capitalism

While interest in rentier capitalism has grown in the 21st century, the relationship between land and rent has long been a central focus of the study of capitalist urban development. Since the 1970s, critical urban geographers have emphasised the importance of class and power to analysing land rent dynamics (Ward and Aalbers 2016). In his elaboration of Marx's theory of land rent, Harvey (2006) argues that the function of private property is to afford landlords monopoly power to appropriate rent—understood as a claim on the fruits of others’ labour. This inevitably leads to the speculative treatment of land as a “pure financial asset which is bought and sold according to the rent it yields” (Harvey 2006:347). Subsequent research has demonstrated that the assetisation of land has been central to the emergence of financialised urban economies since the 1980s (Ward and Swyngedouw 2018). While assetisation is identified by Harvey as a general tendency of capitalist development, Haila (2015) observes that rent is a geographically and historically contingent social relation between landlord and tenant. As such, although the monopoly power of private property is a necessary condition of rent, the specific form that rent takes is conditional on situated class relations and power dynamics. In order to understand the urban geographical dimensions of rentier capitalism, therefore, it is necessary to adopt a multi-scalar conjunctural approach that recognises the dialectical relationship between general tendencies and socio-spatial particularities (Leitner and Sheppard 2020).

The situated analysis of land rent dynamics has gained popularity in global urban studies to explain how the rentier practices of diverse actors, from private equity firms to peri-urban villagers, are shaping Southern urban transformations (Cowan 2022; Desai and Loftus 2013; Leitner and Sheppard 2020; Pati 2022). However, this literature has largely focused on Asia to date, raising questions about the geographical dimensions of rentier capitalism in other contexts situated at the frontier of global urbanisation processes. One such context is Africa, and in particular East Africa, which is currently the least urbanised but fastest urbanising region in the world (Goodfellow 2022). While this transformation has contributed to mainstream discourses celebrating Africa “rising”, there has also been a resurgence of academic interest in critically analysing the dynamics of capitalism on the continent (Chitonge 2018; Goodfellow 2020; Ouma 2017). Anthropologists have argued that the concept of rentier capitalism has utility for understanding the practices of African businesspeople, with a particular focus on how individual entrepreneurs rely on privileged access to political elites in order to appropriate rents (Bierschenk and Muñoz 2021). The importance of what Bierschenk and Muñoz (2021:19) term “relational capital” to rentiership is evident in contemporary Kenya, where prominent corporations such as the FinTech giant Safaricom enjoy close ties to the country's political dynasties (Donovan and Park 2022). Despite this recent interest in rentier capitalism in Africa, however, there is a lack of research on the urban geographical dimensions of this phenomenon.

This paper responds to Ouma's (2017:504) call for greater attention to be paid to “the complex socio-spatiality of (global) capitalism ‘in Africa’” by exploring the new urban geographies of rentier capitalism in this context. In the process, it builds on research that analyses capitalist expansion as a frontier process. Moore's (2000) scholarship on “commodity frontiers” argues that capitalism has expanded geographically throughout history via the appropriation of uncommodified land and labour. Tsing's (2005) ethnographic account of Indonesian rainforest exploitation characterises capitalist frontiers as spaces of deregulation in which spectacular profits are enabled by the blurring of boundaries between public and private interests and legitimate and illegitimate activities. In the context of urban Africa, the concept of the “real estate frontier” has been employed to analyse capitalist expansion through studies of land privatisation (Gillespie 2020), housing microfinance (Scheba 2023), and infrastructural corridors (Gillespie and Schindler 2022). Regarding the latter, infrastructure has long been recognised as a key determinant of land rent dynamics. For example, Harvey (2006) observed that investment in transport infrastructure enables property owners to capture “differential rents” based on the locational advantages of particular properties (see also Desai and Loftus 2013). As such, studying how infrastructure-led development is shaping the emergence of real estate frontiers can generate insights into the spatiality of rentier capitalist expansion.

This paper examines how road building projects have enabled the expansion of real estate frontiers in Nairobi Metropolitan Region (hereafter Nairobi)—an urban region in south-central Kenya comprising the capital city and surrounding counties of Kajiado, Kiambu, Machakos, and Murang'a. In the process, it makes two key contributions to geographical understandings of rentier capitalism. First, it employs a multi-scalar conjunctural approach (Leitner and Sheppard 2020) to demonstrate how situated urban land rent dynamics are constituted through the inter-relation between the general and the particular. While the assestisation of land is a general tendency of 21st century capitalist development, the spatiality of rentier capitalism in Nairobi is shaped by a particular conjuncture of local settler-colonial legacies, Kenya's clientelist national politics, the rapid urbanisation of East Africa, and the pursuit of infrastructure-led development across the global South. Second, it builds on Tsing's (2005) conceptualisation of capitalist frontiers to argue that Nairobi's peri-urban real estate frontier is characterised by a “grey” mode of development that defies conventional distinctions between the formal and the informal (Smith 2020). This grey development motivates rentier capitalist expansion by creating the conditions for powerful actors to extract large rentier profits.

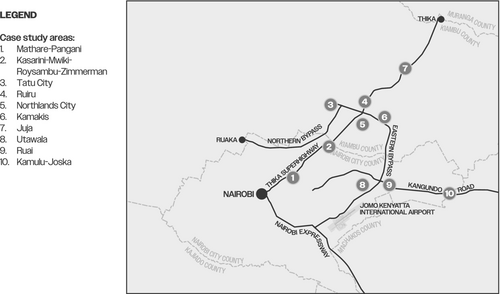

Meth et al. (2021) argue that identifying distinct, yet interrelated, processes of change is key to understanding peri-urban geographies. Following Brenner (2019:349), therefore, this paper adopts an epistemological approach that prioritises “the core processes through which urban(izing) geographies are produced”. It does so by studying the specific processes of land transformation that generate the peri-urban scale in Nairobi. Fieldwork was undertaken in several areas located close to two major road building projects—the Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass (see Figure 1). Interviews were conducted with a range of local real estate market actors such as land brokers, developers, and property managers, as well as long-term residents and local leaders. Individuals operating in the real estate sector are often guarded about their business activities, and accessing these actors was challenging and time consuming. Beyond these immediate areas, interviews were conducted with key actors operating at multiple scales, including urban planners in local government, civil servants in national road agencies, and experts in international real estate companies. 30 interviews were conducted in total between August 2021 and April 2022. Interviews were triangulated with other methods, including: field observations and informal conversations at locations discussed in this paper; participant observation at real estate industry and urban policy events; and analysis of policy, planning, and project documents, real estate marketing materials, local media reports, and land market and population databases.

Infrastructure-Led Development and Urbanisation in Nairobi

Infrastructure-led development is a state spatial strategy to achieve social and economic modernisation through enhancing infrastructural connectivity (Schindler and Kanai 2021). A growing literature recognises that, while infrastructure-led development in Kenya may fail to deliver on its promises of national and city regional transformation, it nonetheless has significant socio-spatial consequences by creating opportunities for various actors to engage in the production of urban space (Gillespie and Schindler 2022; Maina and Cirolia 2023; Smith 2019). This paper builds on this research by demonstrating how, in the context of Kenya's clientelist political system, road building in Nairobi has catalysed the production of the peri-urban scale through a piecemeal urbanisation process that defies conventional formal-informal distinctions.

The relationship between transport infrastructure and urbanisation in Kenya dates to the end of the 19th century when the British Empire constructed the Uganda Railway connecting the Port of Mombasa to Lake Victoria. The railway formed the infrastructural basis for the creation of the colonial territory of Kenya, the establishment of European settler agriculture in the “White Highlands”, and the emergence of Nairobi and other urban centres along the route (Kimari and Ernstson 2020; Lesutis 2021). During the post-independence period, plans for new road corridors proliferated across Africa as governments aspired to Pan-African integration and modernisation. Under ambitious plans for a continental “Trans-African Highway”, Kenya constructed tarmac roads in the 1960s–70s, enhancing automobility between urban centres such as Mombasa and Nairobi (Cupers and Meier 2020). Following several decades of underinvestment in the context of neoliberal structural adjustment policies, the Government of Kenya renewed its commitment to infrastructure-led development with the launch of “Kenya Vision 2030” in 2008.

A multi-scalar state spatial strategy to transform Kenya into a middle-income industrialising country, Vision 2030 “aspires for a country firmly interconnected through a network of roads, railways, ports, airports, water and sanitation facilities, and telecommunications” (Government of Kenya 2007:6). At the national scale, megaprojects such as the Lamu Port, South Sudan, Ethiopia Transport Corridor, and the Standard Gauge Railway are intended to catalyse modernisation by addressing regional disparities and enhancing transnational connectivity (Enns and Bersaglio 2020; Kimari and Ernstson 2020). At the city regional scale, the Nairobi Metro 2030 masterplan prioritises investment in transport infrastructure as key to establishing Nairobi as a “world class African metropolis” (Ministry of Nairobi Metropolitan Development 2008:v). This has translated into a focus on large-scale road building projects, typically implemented by central government in a top-down manner with international financiers and engineering firms (Guma et al. 2023; Klopp 2012; Manji 2015). This paper focuses on two Vision 2030 projects of particular significance to urbanisation dynamics in Nairobi: the upgrading of the road connecting the capital to the town of Thika in Kiambu County into an eight-lane “Superhighway”, and the Eastern Bypass project to connect Jomo Kenyatta International Airport to the south of the city with the Thika Superhighway to the north. These projects have their origins in the 1970s and were revived under the banner of Vision 2030 (Maina and Cirolia 2023). Both were funded by the Kenyan government and China's Exim Bank and constructed by Chinese contractors between 2009 and 2014. In addition, the Thika Superhighway was funded by African Development Bank (AfDB) as part of its continent-wide transnational connectivity agenda (see Gillespie and Schindler 2022).

Despite the grand promises of Vision 2030, road building projects in Nairobi have attracted criticism. For example, road expansion has arguably exacerbated the city's traffic problems by encouraging private car ownership (K'Akumu and Gateri 2023; Manji 2015). In response to persistent congestion, there are now plans to retrofit the Thika Superhighway with a Bus Rapid Transit service, and in 2021 the government embarked on the expansion of the Eastern Bypass into a dual carriageway. More broadly, there has been intense public debate around the financing of infrastructure megaprojects. Uhuru Kenyatta's 2013–2022 Jubilee government borrowed huge sums to fund road and railway construction, provoking concerns about the economic viability of large-scale infrastructure investments, the inflation of project budgets by corruption, and the surrender of Kenya's sovereignty to foreign creditors (Lesutis 2021; Ndii 2020). According to one civil servant, the prioritisation of urban road building is motivated by the rent-seeking opportunities generated for elites by high-value construction projects (Officer, Kenya Urban Roads Authority, 6 April 2022; see also Klopp 2012). However, the benefits of public spending on infrastructure are less tangible for the broader population. Kenyan workers must navigate an adverse economic situation characterised by austerity policies, rising living costs, irregular incomes, and escalating indebtedness to mobile lending platforms (Donovan and Park 2022). This stark inequality motivated a turn towards anti-elite populism in the 2022 elections, indicating widespread scepticism that Vision 2030 will deliver on its promises of national prosperity (Lockwood 2023c).

While the economic benefits of infrastructure-led development are disputed, it is beyond doubt that road building has contributed to urbanisation in Nairobi. The Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass projects have catalysed a property boom characterised by skyrocketing land values and the subdivision of former plantations and livestock ranches into plots of urban real estate along the route of both roads (K'Akumu and Gateri 2023; Kinuthia et al. 2021; Manji 2015). Following the route of the Superhighway, an almost contiguous urban corridor now stretches the 45 km distance from Nairobi to Thika town. High-rise blocks of rental accommodation, petrol stations and shopping malls all cluster along the edge of the road where land values are the highest. Further away from the transport corridor, high-density development gives way to a patchwork of gated housing estates and self-built family homes interspersed with undeveloped plots of land. As a result, Nairobi's agrarian hinterlands are now home to rapidly growing urban populations. For example, the municipality of Ruiru is located close to the intersection of the Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass in Kiambu County. Ruiru's population grew from 88,000 in 2000 to 389,000 in 2020 and is projected to increase to 717,000 by 2035 (UN 2018). With an annual population growth rate of 7.7%, this former agricultural town is now Kenya's fourth largest urban centre and has been described as one of fastest growing agglomerations in Africa (Satterthwaite 2021).

Some peri-urbanisation in Nairobi takes the form of master-planned megaprojects. International developer Rendeavour is building “Tatu City”, a 5,000-acre private new city and special economic zone on a former coffee plantation close to the boundary between Nairobi and Kiambu counties. Vision 2030 road building projects were key to Rendeavour's decision to acquire this land in 2008 (Senior Manager, Rendeavour, 24 August 2021). In addition, 11,000 acres of land owned by the Kenyatta family located between both roads is to be developed into another megaproject called “Northlands City”. Despite these exceptions, however, most urbanisation along road corridors follows a piecemeal “plot by plot” logic of subdivision and development in which planning and building regulations are commonly bypassed (Karaman et al. 2020). For example, it has been estimated that as many as 47% of subdivisions close to the Eastern Bypass violate standards for minimum plot sizes (Kinuthia et al. 2021). Similarly, one planner claimed that 60% of new developments in Kiambu county have not received approval for change of land use (Urban Planner, County Government of Kiambu, 31 March 2022). In addition, developers commonly disregard restrictions on maximum building height and plot coverage when constructing high-rise housing (Huchzermeyer 2011). The outcome is the emergence of extremely dense neighbourhoods in which all available space is built upon by developers to maximise profits. These “concrete jungles” are dominated by multistorey rental housing, and suffer from a range of problems, including incompatible land uses, lack of public green space, environmental degradation, traffic congestion, flooding, and the collapse of poorly constructed buildings. This has prompted developers and residents to establish gated communities and neighbourhood associations to collectively regulate development in their immediate area. In addition, lack of public provision means that households rely on private enterprise and self-help to provide basic infrastructure such as water boreholes, septic tanks, and feeder roads.

Plot by plot urbanisation is, in part, the product of institutional fragmentation and limited local state capacity in Kenya (see Cirolia and Harber 2022; Maina and Cirolia 2023). National road agencies did not engage local governments to undertake land use planning for road corridors in advance of constructing the Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass. One planner complained that “the engineers who designed the road never involved the local planners … because people tend to think that transportation comes first and the land use comes after, but it's actually the other way round” (Urban Planner, Nairobi City County Government, 1 April 2022). In addition, although decentralisation in 2010 devolved physical planning powers to county governments, local authorities lack the resources to consistently enforce regulations in rapidly urbanising areas. However, it would be a mistake to simply view plot by plot urbanisation as an “informal” process that signifies the absence or failure of state planning. Rather, as Smith (2020) argues, much development in Nairobi assumes a “grey” character in which state actors are centrally involved in facilitating and benefiting from regulatory bypassing.

Grey development in Nairobi must be understood in relation to Kenya's clientelist political system (Bassett 2020; Huchzermeyer 2011). Kenyan politics since colonialism has centred around the accumulation of wealth by elites and the distribution of resources through ethnic patron–client networks (Berman et al. 2009). This is illustrated by the country's well-documented history of illicit land grabbing, with political elites appropriating public land both for personal gain and to reward their allies (Manji 2020). While the wider public foot the bill for infrastructure spending, Vision 2030 projects have reaffirmed the class power of the elite by generating rent seeking and patronage opportunities in their historical power base of central Kenya (Lesutis 2021). For example, former President Mwai Kibaki (2002–2013) built the Thika Superhighway through the heart of what is known as “Kikuyuland”, enhancing the value of land owned by his wealthy supporters from the Kikyuyu ethnic group. Within this clientelist political context, regulatory non-compliance is facilitated by the collusion of public officials, many of whom have a financial stake in grey real estate themselves (Smith 2020). As a result, urban planners are reluctant to constrain the activities of property owners. According to one such planner, “If agricultural activity is not giving satisfactory returns of the property … a developer or a landowner can use his land as you want to get the returns … definitely you know you can't restrict an owner of land from developing” (Urban Planner, Nairobi City County Government, 1 April 2022). As subsequent sections will illustrate, this “greyness” creates the conditions for rentier capitalist expansion along Nairobi's road corridors.

Road Corridors as Real Estate Frontiers

The remainder of this paper identifies four processes that are driving real estate market expansion in peri-urban Nairobi: commodification; speculation; autoconstruction; and assetisation.

Commodification

Scholars of agrarian reform in Africa demonstrate that indigenous common property on the continent has been subject to continual processes of enclosure since the late 19th century (Okoth-Ogendo 2002). Land commodification in Kenya has been highly uneven: while communal tenure has largely persisted in the dry pastoral north, 70% of land in Nairobi is privately owned (Elliott 2022; Pitcher 2017). Regarding the latter, central Kenya's particular history of settler-colonial dispossession and postcolonial land reform has created the conditions for contemporary real estate market expansion by establishing the status of land as private property. From the end of the 19th century, lands with high potential for cash crop production were alienated to European settlers, while Africans were confined to lower quality land in ethnically segregated “native reserves”. This racialised dispossession provoked the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s, leading to violent state repression and, eventually, Kenya's political independence in 1963. From 1954, the colonial authorities sought to contain nationalist discontent and enhance agricultural productivity by issuing individual freehold titles to African smallholders in the reserves (Harbeson 1971). This market-based land reform approach was continued by Jomo Kenyatta's postcolonial government, who rejected redistributive demands in favour of ensuring economic continuity and protecting the private property of Europeans (Manji 2020). Africans were required to pay market value to acquire land from departing settlers, and groups of Kenyans formed companies to purchase large farms. This process disproportionately benefited wealthy and politically-connected groups, contributing to class and ethnic inequalities that persist today (Kanyinga 2009). As Manji (2020) argues, therefore, the primacy of private property established through settler colonisation was maintained in Kenya's postcolonial political economy.

Following independence, land close to what is now the Eastern Bypass and Thika Superhighway was acquired by group farms for livestock ranching and the production of cash crops such as coffee and sisal fibre. From the 1980s, however, these large collective landholdings were gradually subdivided, with shareholders allocated individual plots according to the size of their equity in the company. These smaller landholdings were less viable as commercial farms, particularly when subdivided further between shareholders’ children. In addition, individual farmers continued to be affected by mismanagement and legal disputes within group farms. From the 2000s, these problems created an incentive for ageing shareholders and their families to sell their plots in response to the growing demand for peri-urban land (Kinuthia et al. 2021). Similarly, the dwindling size of inherited plots has motivated poor smallholder farmers on Nairobi's periphery to sell their ancestral land for development. In the words of one land broker, “I think it's the whole of Kiambu County; everyone is going to real estate more than agriculture” (Land Broker, Ruiru, 14 October 2021).

Despite the postcolonial state's embrace of market-based land reform, commodification in peri-urban Nairobi is not a straightforward process. In central Kenya, the sale of ancestral land is stigmatised on the grounds that fathers are morally obliged to pass on property to their children (Lockwood 2023a). This moral attachment to land as an inter-generational asset can discourage smallholders from alienating their property, complicating the advance of the real estate frontier. When owners do decide to sell, buyers must navigate Kenya's labyrinthine and compromised land bureaucracy to secure their property claim. Title deeds are highly prized, and plots with formal title attract a premium. However, obtaining official documents can be a slow and complex process, and plots are sometimes sold several times without formal title changing hands. This leaves buyers vulnerable to fraudulent transactions and bureaucratic corruption: forged documents circulate, vendors tout land they don't legitimately own, and plots are sold to more than one buyer. Due to the pervasive risk of “purchasing air”, prospective buyers must conduct “due diligence” on the ownership history of specific plots (Housing Developer, Kamakis, 21 September 2021). In addition, property owners seek to ward off rival claims by erecting walls around plots and marking them with “this land is not for sale” signs. In a context where distrust of state institutions and anxieties about deception are widespread (Smith 2020), therefore, land commodification is an uncertain process that requires everyday labour to maintain the monopoly power of private property (see also Cowan 2022; Mercer 2020).

Speculation

Located close to the intersection of the Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass, Ruiru and Kamakis are major hubs for land brokerage in Nairobi. Commercial buildings in both locations contain the offices of many brokerage companies, often adjacent to legal practices that specialise in property conveyancing. These companies buy several acres of agricultural or ranching land and subdivide these holdings into smaller plots, typically between 40 × 60 ft and 50 × 100 ft each. These plots are then sold for a profit as land values rise due to either the anticipated or actual construction of road infrastructure. Respondents agreed that the value of plots close to the Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass had appreciated dramatically as a result of these projects. These claims are supported by industry data indicating that between 2007 and 2019 land prices increased 16-fold in Juja and 11-fold in Ruiru. This compares to a relatively modest six-fold increase in the affluent Nairobi neighbourhood of Kilimani (HassConsult 2019). Occasionally land brokers add value to plots themselves through the provision of basic infrastructure such as boreholes, perimeter walls, and feeder roads. However, in many cases they simply hold onto land until they decide the time is right to subdivide and sell. Plots are often sold to other speculators, and land typically changes hands two or three times before being acquired by someone with the intention to develop.

Some speculators rely on the public announcement of infrastructure plans to acquire land. For example, the announcement of the Thika Superhighway project by President Kibaki immediately triggered speculation in the adjacent settlement of Mathare, with many non-residents acquiring land as an investment. However, due to collusion between politicians, officials, and land brokers, speculation along road corridors usually begins in advance of the public notification of new projects (Kinuthia et al. 2021). Real estate market actors emphasise the importance of “on the ground” knowledge (Developer and Construction Material Supplier, Utawala, 13 September 2021) or “intelligence” (Land Broker 1, Kamakis, 9 September 2021) about road building plans so that they can acquire land at low prices before others. One broker emphasised the importance of social networks to land acquisition: “Knowing people is good. Like our director, he is connected. So if he hears of something, he is able to know what to do next” (Land Broker 2, Ruai, 22 September 2021).

Without connections to those involved in public infrastructure planning, discerning genuine intelligence from false promises becomes difficult. One developer cautioned that “I never buy a plot if someone says ‘tarmac is coming’. It's a very common thing you hear from somebody who is selling plots, they're basically trying to sell you tarmac that doesn't exist. So, unless we have specific intelligence about it, we go to ministries, we talk to engineers about it, what the timeline is on the project and things like that” (Housing Developer, Ruiru, 31 March 2022). In this speculative environment, the language of “tarmac” signifies the importance of state investments to the appreciation of property values, reflecting the entanglement of infrastructure and real estate on the frontier. For instance, adverts for plots often emphasise that the land is “touching tarmac”. In addition, tarmac is the subject of lobbying by peri-urban residents and can be used by politicians to reward support. As the developer quoted above indicates, reliable intelligence about tarmac is the lifeblood of speculation, and access to the state is vital to avoid falling victim to wishful thinking or deception.

Large profits can be made by speculators acquiring land before, during and soon after the construction of roads, especially if on the ground knowledge enables them to move before others. However, once land values have risen to a certain level, speculators face diminishing returns within established road corridors. The closing of this rent gap (i.e. the difference between capitalised and potential rents) prompts speculators to acquire land further away from Nairobi where they anticipate roads will arrive in future. “Right now”, one land broker said, “there are some pieces we are purchasing very far away where there is nothing, but we hope one day there will be from the rumours we hear. We are waiting” (Land Broker 2, Ruai, 22 September 2021). Another emphasised the importance of “seeing tomorrow” and acquiring land in anticipation of future infrastructure, rather than buying in areas already served by major roads (Land Broker, Kasarani, 29 September 2021). Anticipatory practices of speculation have led land brokers to shift their geographical focus away from the immediate corridors around the Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass towards newly urbanising areas such as Kamulu and Joska. In contrast to high density road corridors, these areas are characterised by dirt roads and large areas of undeveloped land interspersed with walled plots where people are incrementally building family homes.

Autoconstruction

Once land has been acquired, subdivided, and transacted by speculators, plots often transfer to individuals who aspire to build a family home in peri-urban Nairobi. Mercer (2020) argues that the African middle class is constituted through the shared practice of acquiring plots and incrementally constructing housing in newly urbanising areas. In Kenya, landownership and housebuilding has long been central to normative expectations of adult masculine success. However, whereas the consolidation of male adulthood was traditionally associated with investment in the ancestral rural homestead, young Nairobians increasingly aspire to build a family house on the peripheries of the capital (Smith 2019). In the context of popular discourses celebrating individual effort and self-reliance, middle-class autoconstruction gives spatial expression to socio-economic stratification as upwardly mobile Kenyans withdraw from wider relations of obligation and focus on the nuclear family home as the “site of success and prosperity” (Lockwood 2023b:329).

Road building has enabled some working age Nairobians to escape rental housing and pursue their middle-class aspirations by relocating to peri-urban areas where plots for housebuilding are relatively affordable. One land broker explained that “people currently living in Nairobi, you find they are tired of paying rent. You have somebody who knows like ‘I am probably going to work in Nairobi for the rest of my life’ and they don't want to pay rent, they want to build their own homes”. Another proudly stated that “as a company, our motto is turning tenants into landlords” (Land Broker, Kasarani, 29 September 2021). In the words of one local real estate expert, therefore, a major driver of urban expansion is the desire of workers to “escape from the problem of rent” (Analyst, Large Real Estate Developer, 20 April 2022). Although formal mortgage finance is not accessible to the vast majority of Nairobians, many households join savings and credit cooperatives (SACCOs) and social groups (“chamas”) to fund land acquisition and incremental construction (Mwau et al. 2020). In some cases, these self-builders simply buy an unserviced plot from a land broker and must arrange service provision themselves by engaging private providers. In others, they acquire a plot within a “gated community” in which some basic infrastructure, such as access roads and drainage, is provided and development is restricted to low-rise family homes.

Previously undeveloped areas adjacent to the Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass were initially inhabited by the self-build owner-occupiers described above. However, rapidly rising land values and the expansion of minibus (“matatu”) public transport services to newly urbanising areas has catalysed a shift to developers acquiring land for high-rise blocks of rental accommodation instead. The verticalisation of formerly low-density residential areas creates displacement pressure for the established inhabitants. Residents close to the Eastern Bypass have found themselves increasingly surrounded by high-rise housing blocks, roasted meat (“nyama choma”) joints and bars, losing their privacy in the process. While the upwardly mobile seek to escape renting in Nairobi's high-rise neighbourhoods, therefore, the displacement pressure they experience from peri-urban verticalisation illustrates the precarity of their middle-class status (see Lockwood 2023b; Mercer 2020).

Some inhabitants respond to displacement pressure by selling their plot and relocating. Others move elsewhere but retain their plot and build rental blocks on site themselves. In some cases, homeowners remain in place but build rental accommodation adjacent to their own property. On one field visit we met Sarah, who escaped renting in the Pipeline settlement in central Nairobi by building a house on a plot near Eastern Bypass. As the area around her house densified, she built a four-storey block of flats and commercial units on the same plot. She told us that she is now considering demolishing the house, extending the flats to the entire plot, and relocating further out. The displacement of self-build owner-occupiers has created demand for plots in newly urbanising areas where speculators have already moved in anticipation of future road building. Just as speculators rely on intelligence about planned infrastructure projects, so aspiring homeowners prioritise proximity to tarmac when buying plots. For example, plans to expand the Kangundo Road that runs east from the Eastern Bypass into Machakos County is currently driving demand amongst self-builders for plots close to Kamulu and Joska (Land Broker, Kasarani, 29 September 2021). As these inhabitants are displaced to emerging urban settlements, the built environment within established road corridors is increasingly shaped by rentier logics.

Assetisation

Having passed though the phases of commodification, speculation, and autoconstruction, land close to the Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass is now largely bought by developers seeking to build for profit. This has led to the verticalisation of road corridors as low-density housing is replaced with high-rise blocks of rental accommodation with ground floor commercial units. These blocks are typically four to ten storeys tall and cover 100% of each plot in violation of building regulations. In addition to rental housing, some developers build gated estates of finished houses for sale or commercial and industrial property such as petrol stations, shopping malls, and warehouses. This phase of development is characterised by the growing treatment of land as a financial asset and the rentierisation of peri-urban space. As such, explaining the densification of road corridors requires an understanding of how rentier logics are pursued by various actors in Nairobi. To this end, Leitner and Sheppard's (2020:500) concept of “inter-scalar chains of rentiership” provides a framework to analyse how “the assetisation and financialisation of land emerges from a diverse set of actors and institutions, operating at scales ranging from the global to the local, each seeking to appropriate land rent”.

Actors operating at multiple scales coalesce around the opportunities for land rent appropriation generated by major road infrastructure projects in Nairobi. While real estate investment in the city is largely dominated by domestic capital, the pro-capitalist orientation of the postcolonial Kenyan state has enabled multinational actors to assume a significant role in this sector (Pitcher 2017). Rendeavour, the developer of Tatu City, is privately owned by investors from New Zealand, Norway, the UK, and the US, and is currently building seven new cities in five African countries. Other global actors include the London-based private equity firm Actis who have built “Garden City”, a mixed-use project on the Thika Superhighway that includes apartments, houses, offices, and a large, but thus far poorly patronised, shopping mall. In addition to private capital, major projects such as Garden City and Tatu City have attracted investment from development finance institutions such as British International Investment and the US International Development Finance Corporation, as well as multilateral organisations such as AfDB and the International Finance Corporation.

Regarding national actors, Kenya's political and economic elite have amassed significant land wealth since independence, enabling them to capitalise on road building projects. For example, it has been alleged that the decision to expand the Eastern Bypass was influenced by then-President Uhuru Kenyatta's desire to enhance the value of the Northlands site (Kenyan Wall Street 2018). On a smaller scale, national elites have invested in high-rise blocks of rental accommodation close to the Thika Superhighway and Eastern Bypass. The ownership and financing of these properties is deliberately opaque, and landlords employ intermediaries to shield their identities from tenants and the public. However, it is common knowledge that powerful individuals such as politicians, civil servants, and senior businesspeople own multiple blocks of rental housing. While some landlords raise bank loans to fund development, the available evidence suggests that high-rise housing tends to be financed through savings and profits from other capitalist endeavours such as matatu ownership (Huchzermeyer 2011). In addition, lack of regulation means that construction is the preferred sector for laundering illicit money (Ambani 2024).

High-rise renting offers young workers a foothold in the urban labour market that they hope will propel them to middle-class success (Schmidt 2024). Housing quality and cost is heterogenous and includes both tenements where low-income households occupy a single room with communal facilities and self-contained flats with private bathrooms for young professionals. In Juja, for example, rents range from KSH4,000 for a room in a tenement to as much as KSH35,000 for a two-bedroom apartment (Property Manager, Juja-Utawala, 18 September 2021). Mwau et al. (2020) calculate that building low-quality, overcrowded tenements is up to four times as profitable as high-income housing, and individuals involved in managing these properties claim that landlords recoup their initial investment in just three to four years (Property Manager, Juja, 18 October 2021; Property Manager, Ruiru, 14 October 2021). Since rent is a claim on the fruits of others’ labour, high-rise landlordism parallels mobile lending as a means through which Kenya's propertied elite extract value from Nairobi's workers (see Donovan and Park 2022).

Absentee landlords typically rely on local actors to manage their investments and protect their anonymity, and a growing number of property management companies offer rent collection and maintenance services. These companies play a key role in the assetisation of land by assuming the risk for rent collection from tenanted units. This ensures a reliable income stream for landlords and enables them to access bank loans for construction by borrowing against future rents. However, assetisation is not risk free: the COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant drop in occupancy rates as tenants sought to cut housing expenditure by moving to cheaper units or returning to their rural family homes. In addition, one property manager commented that high land costs combined with growing competition for tenants was making it increasingly difficult to meet landlords’ expectations for returns. This narrowing of the rent gap led them to conclude that absentee landlords are “being sold lies” by speculators, raising false hopes of how much profit they can extract in an increasingly saturated market (Property Manager, Roysambu, 30 September 2021).

Finally, in contrast to moralistic discourses that contrast “good” productive activities with “bad” rent extraction, a critical analysis of rentier capitalism requires an appreciation of how practices of rentiership emerge in relation to the growing global hegemony of asset-based social reproduction (Birch and Ward 2023, 2024). This is pertinent in Kenya's contemporary conjuncture of rising living costs, volatile incomes, and growing indebtedness, where “hustling” in insecure employment is the norm and most of the population are not served by pension schemes (Donovan and Park 2022; Lockwood 2023c; Thieme et al. 2021). In this context of widespread economic precarity, supplementing diverse and unstable livelihood activities with regular rental income offers middle-class households a prized route to (relative) financial security. For example, one developer who builds finished houses for sale explained that these properties are largely bought by middle-aged individuals as a source of retirement income rather than a place to live (Housing Developer, Ruiru, 31 March 2022). In addition to a means of elite accumulation, therefore, owning urban property as a rental asset is a popular aspiration through which Nairobians seek to secure their future.

Leitner and Sheppard's (2020:501) account of inter-scalar chains of rentiership documents “the emergence of an urban rental economy” in Jakarta and Bangalore. As discussed above, however, Nairobi's urban rental economy emerged in the early 20th century through the particular conditions of settler-colonial urbanism (White 1990). In 21st century Nairobi, therefore, road building projects have catalysed the geographical extension of the urban rental economy. This extended rental economy incorporates a diverse range of actors operating across multiple geographical scales and disrupting formal–informal distinctions, from global private equity firms building shopping malls to middle-aged individuals buying houses as a pension assets. As the concept of a chain suggests, the rentier practices of these actors are interdependent. For example, the Tatu City project has attracted migrant workers to Ruiru, creating opportunities for national and local actors to provide rental accommodation in the process. As Meth et al. (2021) argue, therefore, large-scale infrastructure and real estate investments in peri-urban areas act as a “vanguard” for wider processes of land transformation.

Conclusion

This paper demonstrates that rentier capitalism in Nairobi is spatialised through the dramatic extension of real estate frontiers along the route of road corridors. It is through this rentier capitalist expansion that the peri-urban scale is produced. Four processes of land transformation drive this expansion: commodification; speculation; autoconstruction; and assetisation. While these processes are distinct, they are also interrelated. Ouma (2024) observes that things must be commodified before they can become assets, and Nairobi's history of settler-colonial land dispossession and market-based land reform has created the necessary conditions for the contemporary rentierisation of peri-urban space. However, while one process often follows another in the sequential manner described above, it is not the case that the frontier advances in a linear, uniform, or smooth fashion. In some instances, for example, land brokers will sell plots directly to rentier developers, and the phase of autoconstruction is skipped altogether. In addition, the plot-by-plot character of development means that processes of speculation, autoconstruction and assetisation can overlap or occur simultaneously in the same area, creating a patchwork of conflicting land uses. Furthermore, processes of autoconstruction and assetisation often exist in tension with one another, as self-builders acquire plots in increasingly peripheral locations to escape the urban rental economy. Finally, although real estate market expansion has resulted in the loss of agricultural and ranching land, rural livelihood activities such as livestock grazing persist in the undeveloped spaces between buildings. Rather than the smooth and total subsumption of the agrarian by the urban, therefore, the peri-urban real estate frontier advances in an uneven and non-uniform fashion (Cowan 2022).

The case of Nairobi illustrates how situated urban land rent dynamics are shaped by the articulation of general economic transformations and contingent social relations. While assetisation is a general tendency of 21st century capitalist development, Nairobi's urban geography of rentier capitalism is the outcome of the particular configuration of officeholding, land ownership, and class power that characterises Kenya's postcolonial political economy. Kenya's history of elite land grabbing and clientelism illustrates how connections to political office have shaped property accumulation and class formation since colonialism. This paper demonstrates how infrastructure-led development in Nairobi has enhanced this fusion of political and economic power. For example, collusion with state actors has enabled speculators to acquire peri-urban land prior to the public announcement of road infrastructure projects, capitalising on huge rent gaps in the process. In addition, the impact of clientelism on urban planning has enabled landlords to maximise differential rents by constructing poor-quality, high-density apartment blocks on small plots close to major roads. This demonstrates how proximity to the political elite, or “relational capital” (Bierschenk and Muñoz 2021:19), is central to practices of rentiership in Nairobi. Just as it is impossible to separate corruption from the “normal” economy (Manji 2020), therefore, the elite rent-seeking associated with large-scale infrastructure projects is intimately connected with the broader dynamics of rentier capitalism in this context. Building on Tsing's (2005) conceptualisation of capitalist frontiers as spaces of deregulation, Nairobi's grey development creates the conditions for rentier capitalist expansion through a frontier process that blurs the boundaries between public and private interests and legitimate and illegitimate activities.

The urban geography of rentier capitalism analysed in this paper is the product of a specific conjuncture characterised by the growing centrality of rentiership to global capitalism, the expansion of connective infrastructure across the global South, East Africa's urban transformation, Kenya's clientelist political system, and the ongoing influence of settler colonialism on Nairobi's land and housing markets. It remains an open question whether the urban geographies of rentier capitalism will assume a similar form in other contexts. Future research should address this question by analysing rentier capitalist expansion in relation to urban, national, regional, and global process of change. Furthermore, understanding the urban geographical dimensions of rentier capitalism is not simply an academic question—it is also a political one. Documenting the expansion of real estate frontiers can inform social movement and policy initiatives that seek to constrain the power of rentiers and support inhabitants to exercise greater democratic control over urban development processes. In Nairobi, the declaration of the Mukuru settlement as a “special planning area” has sought to challenge the unbridled power of property owners by involving low-income tenants in participatory decision-making processes regarding physical upgrading (Ouma 2023). Future research can complement such initiatives by generating knowledge on the political-economic conditions that either enable or constrain rentier capitalist expansion.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the anonymous Antipode reviewers for their insightful comments and Alex Loftus for editorial guidance. Earlier versions of the paper received helpful feedback from Smith Ouma and participants at several research events in 2023: the RGS-IBG conference in London; a workshop on “Home-Grown Growth in African Cities” in Accra; and a Global Urban Futures research group seminar at the University of Manchester. We are also grateful to Stephen Mutungi for research assistance and Glen Cutwerk for map design. The research received funding from a University of Manchester Hallsworth Fellowship and the African Cities Research Consortium, with support from UK International Development.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.