Simulation-based education in the Pacific Islands: educational experience, access, and perspectives of healthcare workers

Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends simulation-based education (SBE) to acquire skills and accelerate learning. Literature focusing on SBE in the Pacific Islands is limited. The aim of this study was to determine Pacific Island healthcare workers' experiences, perspectives, and access to SBE.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey of Pacific Island healthcare workers. We designed an online questionnaire based on existing literature and expert consultation. The questionnaire included Likert scales, multiple-choice, multi-select and open-ended questions. Participants were healthcare workers recruited from professional networks across the region. Descriptive statistics and relative frequencies summarized data, and comparative testing included unpaired t-tests, Mann–Whitney U, Chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests. Free-text responses were presented to illustrate findings.

Results

Responses from 56 clinicians working in 11 Pacific Island countries were included. Fifty were medical doctors (89%), including 31 (55%) surgeons. Participants reported experience with scenario-based simulation (73%), mannequins (71%), and simulated patients (61%). Discrepancies were identified between previous simulation experience and current access for simulated patients (P = 0.002) and animal-based part-task trainers (P = 0.002). SBE was seen as beneficial for procedural skills, communication, decision-making and teamwork. Interest in further SBE was reported by most participants (96%). Barriers included equipment access (59%), clinical workload (45%) and COVID-19 restrictions (45%).

Conclusion

Some Pacific Island healthcare workers have experience with SBE, but their ongoing access is predominantly limited to low-technology modalities. Despite challenges, there is interest in SBE initiatives. These findings may inform planning for SBE in the Pacific Islands and may be considered prior to programme implementation.

Introduction

With a global shortfall of 10 million health workers expected by 2030, workforce training has been identified as an important method of addressing health inequities.1, 2 Simulation-based education (SBE) has been recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a strategy to accelerate training and meet workforce needs, and there is growing interest in the technique in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).3-5

Simulation may be defined as a technique to ‘replace or amplify real experiences with guided experiences that evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive manner’.6 Many modalities of SBE are increasingly used in healthcare to improve quality of care and enhance patient safety.7-9

The Western Pacific Region includes countries of diverse size, wealth and populations.10 Many are classified as Small Island Developing States (SIDS) by the United Nations, and have ‘unique social, economic and environmental vulnerabilities’.11, 12 Pacific SIDS face distinct challenges relating to geographic and economic isolation, with small populations spread across remote areas.11 They also experience disproportionately high rates of communicable and non-communicable diseases. These challenges occur on the background of lower workforce densities, with difficulty training and retaining sufficient numbers of healthcare workers.13-16

Consistent with the WHO's recommendation, SBE has been discussed as a priority in stakeholder meetings for the Pacific region.3, 17 SBE may improve and accelerate healthcare worker training in LMICs, while maximizing patient safety.3, 5 These advantages suggest SBE has significant potential to address workforce needs in the Pacific Islands. Despite this, literature focusing on SBE in the Pacific Islands is limited. Studies focus on specific educational initiatives and no publications investigate the use of the technique more broadly.18-22

The primary aim of this study was to determine the experiences of Pacific Island healthcare workers with SBE, as well as their current access and perspectives on its use. We also aimed to explore barriers limiting access to SBE.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of healthcare workers in the Pacific Islands. The reporting of study methods was guided by the CROSS guidelines for reporting survey studies.23

- Simulated (standardized) patients/role-play

- Scenario-based simulation

- Mannequins

- Synthetic part-task trainers (PTT)

- Animal-based PTT

- Cadaveric PTT

- Bench trainers (e.g., laparoscopic trainers)25

- Extended reality (virtual/augmented/mixed reality) simulation26

- Online simulation/telesimulation

- Computer- or screen-based simulation

- Hybrid simulation – combining two or more simulation modalities

The questionnaire included Likert scales, multiple-choice, multi-select and open-ended questions. Questions were informed by simulation research, and were reviewed by experts in global health, health education and survey design. Recommendations were made that improved cultural sensitivity (e.g., asking for ‘years of experience’ as a proxy for age). The questionnaire underwent multiple rounds of revision for clarity and fluidity.

Participants were invited via email to complete the questionnaire from May to July 2022. Organizational leaders were also engaged to disseminate the information to prospective participants. Snowball sampling was encouraged, with recipients able to forward the questionnaire to eligible colleagues. A sample size calculation was not conducted as the study aimed to understand the experiences of a sample of healthcare workers, rather than extrapolate to the broader population of Pacific Island healthcare workers. No incentives were offered for completion of the questionnaire.

The survey was conducted using the Qualtrics™ online platform (Qualtrics, Utah, USA). Questionnaire data were anonymous by default. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the primary researcher's institution (Reference number: 31266). Participants were assured that responses were not identifiable unless they volunteered their contact information.

Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel™ (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, USA) and GraphPad Prism™ (GraphPad Software Inc., Massachusetts, USA). Duplicate responses were identified and excluded when participants volunteered their emails. Descriptive statistics and relative frequencies were generated, and comparative testing was conducted. This included unpaired t-tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, Chi-squared tests, and Fisher's exact tests as appropriate. If one country or occupation exceeded 40% of the sample, we planned to conduct a subgroup analysis to ensure the data were not significantly affected by these factors. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Free-text responses expressing perspectives and experiences were reported descriptively to illustrate findings.32

Results

Participant demographics

Seventy-one responses were received and 56 were included in the final analysis. Partial responses (7), duplicate responses (4) and non-Pacific Island participants (4) were excluded. Eighteen responses to open-ended questions were received (Supplementary Material 2).

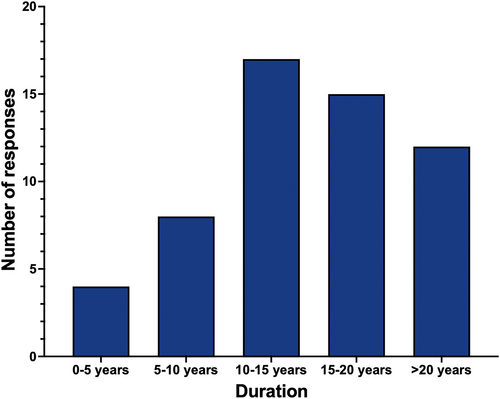

Thirty-two participants (57%) had between 10 and 20 years of professional experience, while 12 (21%) had greater than 20 years of experience (Fig. 1). Thirty-one participants (55%) identified as male.

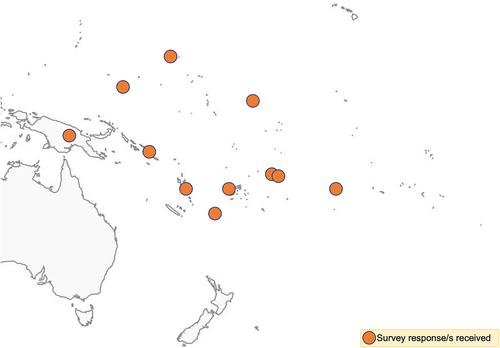

Responses were received from clinicians working in 11 Pacific Island countries (Fig. 2). Fiji was the most common country of practice (42%) (Table 1).

| Country | Frequency (n = 56) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| American Samoa | 1 | 2 |

| Australia† | 1 | 2 |

| Cook Islands | 2 | 4 |

| Federated States of Micronesia | 1 | 2 |

| Fiji | 24 | 43 |

| Kiribati | 2 | 4 |

| Marshall Islands | 1 | 2 |

| Papua New Guinea | 5 | 9 |

| Samoa | 8 | 14 |

| Solomon Islands | 4 | 7 |

| Tonga | 4 | 7 |

| Vanuatu | 3 | 5 |

- † This participant was included as they were originally from a Pacific Island country.

The questionnaire was completed by 50 medical doctors (89%), five nurses/midwives (9%) and one allied healthcare worker (2%). The most common specialty of participants was surgery (55%), followed by anaesthetics (18%).

All participants had at least tertiary-level education, with 40 (71%) having a higher degree.

Experience as educators

Forty-one participants (73%) were involved in the professional development of others. Of these, 21(51%) dedicate between 1 and 5 h per week to this, while four (10%) dedicate greater than 20 hours per week. Twenty-four trainers (59%) supervise both undergraduate and post-graduate learners. Twenty-nine educators (71%) were formally recognized by their institution as supervisors or trainers. However, of those formally recognized, only 15 (52%) were reimbursed. Reimbursement was most commonly financial (87%) and in the form of other professional benefits (27%).

Simulation experience and access

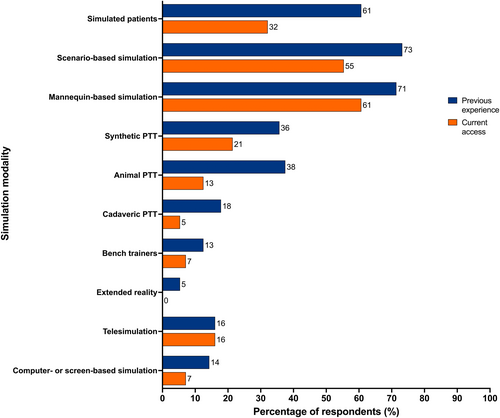

Forty-two participants (75%) had previous experience with SBE, while two selected ‘unsure’ (4%). Subgroup analysis compared Fijian and non-Fijian participants, as well as surgeon and non-surgeon participants. There was no significant difference between previous simulation experience among Fijians and non-Fijians (83% versus 69%, P = 0.35), as well as surgeons and non-surgeons (77% versus 72%, P = 0.76). SBE most commonly took the form of scenario-based simulation (73%), mannequins (71%), and simulated patients (61%) (Table 2). Experience with other modalities was limited, such as bench trainers (13%) or extended reality (5%).

| Modality | Frequency (n = 56) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario-based simulation | 41 | 73 |

| Mannequins | 40 | 71 |

| Simulated patients | 34 | 61 |

| Animal-based PTTs | 21 | 38 |

| Synthetic PTTs | 20 | 36 |

| Cadaveric PTTs | 10 | 18 |

| Telesimulation | 9 | 16 |

| Hybrid simulation | 9 | 16 |

| Computer or screen-based simulation | 8 | 14 |

| Bench trainers | 7 | 13 |

| Extended reality | 3 | 5 |

Of those exposed to SBE, most had experience from their own institution (67%), while receiving training from visiting organizations (50%) or travelling overseas for training (50%) was also common.

Many participants had ongoing access to simulation (68%). This was usually mannequins (61%) or scenario-based simulation (55%) (Fig. 3). A discrepancy was evident when comparing previous simulation experience and current access to simulation modalities, with statistically significant differences observed for simulated patients (P = 0.002) and animal-based PTTs (P = 0.002). The p value for scenario-based simulation was P = 0.049. Limited or absent ongoing access was observed for certain modalities such as bench trainers and extended reality.

Participants reported completion of numerous simulation courses which are listed in Supplementary Material 3.

Barriers to simulation-based education

Barriers limiting access to SBE were identified, most commonly “equipment access” (59%), ‘excess clinical load’ (45%) and COVID-19 restrictions (45%). Less frequently reported barriers were ‘unfamiliarity with SBE’ (27%), ‘lack of opportunity’ (21%) and ‘reliance upon visiting teams’ (18%).

Sometimes I am too exhausted to be able to focus on my own CME [Continuing Medical Education].

(Anaesthetist-1)

[I] do not have a space to conduct simulations as often as I would like.

(Anaesthetist-2)

Simulation attitudes and perspectives

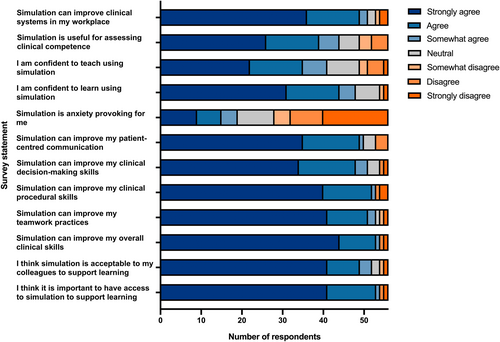

Attitudes towards simulation for quality improvement, teaching, and learning were generally positive (Fig. 4). SBE was seen as beneficial for procedural skills, communication, decision-making and teamwork.

Fifty-three participants agreed or strongly agreed that it was important to have access to simulation (95%). Thirty-five agreed or strongly agreed with the statement of “I am confident to teach using simulation” (63%).

Significant demand for SBE was illustrated, with 54 participants (96%) expressing interest in further training. Only two participants (4%) were not interested in SBE. One of these had never experienced SBE, while the other was unsure about whether they had previous SBE experience.

Non-significant differences were observed for most questions in the subgroup analysis. For one statement, ‘I am confident to learn using simulation’, surgeons reported significantly more confidence compared to non-surgeons (median 7 versus 6, P = 0.04). For another, ‘Simulation is useful for assessing clinical competence’, non-Fijians scored higher when compared to Fijians (median 7 versus 6, P = 0.03).

SBE may be essential to maintain clinical skills in the Pacific Island nations where clinical workload may not be adequate to maintain clinical expertise.

(Surgeon-1)

This will be a way to solve our limited resources while training can be available locally.

(Surgeon-2)

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that current access to SBE may be insufficient in the Pacific Islands. This is despite almost all participants desiring further SBE.

Most participants had some experience with SBE, with half having exposure through their own institutions. Ongoing access was reported by most participants. However, modalities were typically low technology. There was significant support for SBE in the Pacific Islands despite numerous reported barriers.

We believe this is the first study to investigate simulation as an educational technique in the Pacific Islands. Previous publications have mainly focused on specific, short-term educational initiatives, and minimal data are available regarding the educational contexts.19-22 Due to the absence of comparable literature, results of this study are compared to publications from other settings.

The Pacific Island healthcare workers in our study reported previous experience with various SBE modalities, predominantly mannequins, scenario-based simulation, and simulated patients. This is consistent with a review of simulation in LMICs conducted by Puri et al., which found low-technology modalities, such as mannequins and simulated patients to be most prevalent.5 The predominant use of low-technology simulation may be explained by the greater expense of high-technology simulators, which is consistent with equipment access being the most-reported barrier in this study. Alternatively, participants may recognize that high-technology simulation is not required for effective education, with evidence suggesting low-technology simulation can be equally impactful.33-36 In recent years, there has been a shift away from the concept of physical fidelity in simulation, with an increased focus on functional task alignment.37 As such, low-rates of high-technology simulation is not necessarily cause for concern in this setting. The high rates of scenario-based simulation in this survey were not reported by Puri et al. as they did not include scenario-based simulation as a modality, reflecting the challenge of categorizing simulation modalities. This issue has been identified within the SBE community, and suggests a need for clearer guidelines.38

There was a discrepancy between previous experience and current access to simulation modalities. This suggests that SBE initiatives may be sporadic and short-term and could include training from external teams that is not sustained. Statistically significant differences were observed for simulated patients and animal-based PTTs. These may be explained by distinct features of these simulation modalities, specifically the efforts required to sustain them. Trained simulated patients require organized and ongoing support, while animal-based training is similarly complex to maintain.39, 40 Conversely, access to certain modalities, such as mannequins or synthetic PTTs, is likely to persist until resources are depleted or equipment breaks down.

Participants expressed strong support for SBE, a reaction which has also been noted in response to previous simulation-based programmes in this setting.19, 21, 22 Given the importance of learner engagement for effective SBE, this is a positive sign for future SBE programmes in the Pacific Islands.41

There was minimal difference between surgeons and non-surgeons, as well as Fijians and non-Fijians, when subgroup analysis was conducted. While the responses to two perspective statements differed significantly, their clinical (or practical) significance is likely minor due to their small median difference.

Reported barriers provide insight into difficulties conducting SBE and have been referenced in previous publications to varying degrees. Equipment access has been widely referenced across the simulation literature in LMICs.4, 40, 42, 43 This is a greater barrier for high-technology modalities, which is consistent with the findings of this study. However, given many modalities of simulation can be conducted effectively with minimal equipment, it is important that excessive emphasis is not placed on physical resources.5 Excessive clinical workloads have also been identified as a major challenge in LMICs with significantly lower provider density than HICs. A study by Bulamba et al. discussed this when implementing a simulation-based programme in Uganda.44 In the Pacific context, establishing that clinical workload inhibits educational participation for some clinicians is notable. This is a complex, multi-faceted issue should be considered in the initiation of new programmes. With workload inhibiting engagement in training, enablers such as accessible training, institutional support and funding for professional development may need to be leveraged.45

Additional challenges uncovered in this study include COVID-19 restrictions, unfamiliarity with SBE and reliance on visiting teams, factors which are less reported in the literature. Several publications elsewhere report positive impacts of COVID-19 on SBE use, suggesting the pandemic had a catalysing effect.46, 47 While this may be true sometimes, it is evident that COVID-19 restrictions can also have a negative effect on medical education, particularly on in-person education.48 The results of this study suggest that this was the case for the Pacific Islands, which may be due to difficulty transitioning to an online education model in low-resource settings.49 While the impact of COVID-19 is reduced at the time of writing, proactively strengthening health education systems may reduce the impacts of future challenges that inhibit in-person activites.50 Finally, the challenge of unfamiliarity with SBE and reliance on visiting teams is consistent with the high prevalence of externally delivered training and large number of short courses reported. This may suggest insufficient integration of SBE into educational curricula within this region; however, further investigation of training programmes would be required to confirm this.

The primary limitation of this study is its sample size. It proved difficult to receive responses from healthcare workers outside of prospectively sampled professional networks. As such, the disciplines of participants did not accurately reflect the proportions of the region's workforce. This may have been exacerbated by gendered and occupational hierarchies between doctors and nurses, with nurses potentially feeling less empowered to contribute.51 There was also significant representation of Fiji in the sample, which may have greater resources than other Pacific Island countries. Despite largely non-significant findings for subgroup analysis, it is possible this influenced the results. Another limitation is the absence of a response rate. This is due to the survey being online and using snowball sampling, which meant the total number of recipients could not be determined. Despite this, it is evident that survey sample was a small proportion of the total population of Pacific Island healthcare workers. However, we remain confident that this insight into the experiences of a number of Pacific Island healthcare workers remains useful to plan educational programmes. Regarding question types, one issue with using multiple choice questions is that they cannot provide context or investigate a phenomenon's complexity.52 Likert scales have also been criticized for bias, as well as their analysis as interval data.53-55 Nonetheless, they remain useful methods of measuring participant opinion, and both are quick and convenient to administer.56, 57 To address limitations of other techniques, open-ended questions enabled capture of any additional perspectives.58 As for any questionnaires of this nature, there is potential for recall and response bias. Participants with negative views of simulation may have been less likely to respond, while others may have felt obliged to respond positively to initiatives suggested by an external provider. We aimed to minimize this by reassuring participants that their responses would be anonymous. Despite these limitations, questionnaires remain a valuable approach for gathering baseline data to guide future research. A final issue to note is that conducting multiple subgroup analyses has potential to result in false positives, which may have been the case for the two statistically significant differences observed in our comparisons.59

This study provides the first insights into the landscape of SBE in the Pacific Islands. The findings suggest that some Pacific Island healthcare workers have previous experience with SBE, but their ongoing access is largely limited to low-technology modalities. Despite several reported challenges, there is significant interest in further SBE. These results can be used to guide implementation of educational programmes in this setting. Where appropriate, SBE should be considered as a method of healthcare worker education, and simulation educators should consider the perspectives and barriers reported in this study to optimize their programmes. Future research should focus on engaging greater numbers of Pacific Island healthcare workers through a wider variety of clinical networks, including those of nursing staff and allied health. The experiences and perspectives of healthcare workers reported in this study may be considered prior to the implementation of future SBE in the Pacific Islands.

Author contributions

Samuel James Alexander Robinson: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Elizabeth McLeod: Conceptualization; methodology; supervision; writing – review and editing. Debra Nestel: Formal analysis; methodology; supervision; writing – review and editing. Maurizio Pacilli: Investigation; supervision; writing – review and editing. Ramesh Mark Nataraja: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; writing – review and editing.

Funding information

No funding was acquired for the purposes of this publication.

Acknowledgement

Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley - Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

Dr. Elizabeth McLeod is an Editorial Board member of ANZ Journal of Surgery and a co-author of this article. To minimize bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication. Ethical approval was granted prior to conducting this study.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.