Prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy to improve wound healing rates following ileostomy closure: a randomized controlled trial

Thomas Tiang and Corina Behrenbruch are equal first author.

Abstract

Background

Reversal of ileostomy is associated with morbidity including wound infection and prolonged wound healing. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been shown to reduce time to wound healing by secondary intention. The aim of this study was to determine whether NPWT improved wound healing rates, compared with simple wound dressings, in patients undergoing reversal of ileostomy where the skin wound is closed with a purse-string suture.

Methods

This was a dual-centre, open-label, randomized controlled trial with two parallel intervention arms. Patients undergoing elective loop ileostomy reversal were randomized 1:1 to receive NPWT or simple wound dressings. The primary endpoint of the study was assessment of complete wound healing at day 42 post reversal of ileostomy and the secondary endpoints were patient-reported wound cosmesis using a visual analogue scale and rates of surgical site infection (SSI).

Results

The study was conducted from June 2018 to December 2021. The trial was approved by the local ethics committee. We enrolled 40 patients, 20 in each arm. One patient in each arm was lost to follow up. Nine patients (9/19, 47.36%) in the simple dressing group had wound healing vs. 13 patients (13/19, 68.42%) in the NPWT group (P = 0.188). There was no significant difference in patient- reported wound cosmesis or SSI.

Conclusion

There was no difference in wound healing rates when comparing NPWT to simple wound dressings at early and late time points post reversal of ileostomy, where the skin wound was closed with a purse-string suture.

Introduction

Advances in surgical techniques and neoadjuvant treatment have led to an increase in sphincter preserving, restorative rectal resections. Unfortunately, low rectal anastomoses, particularly those following neoadjuvant radiotherapy, carry a significant risk of anastomotic leak. As a result, a diverting loop ileostomy is often formed to mitigate the clinical consequences of an anastomotic leak.1, 2

Ileostomy closure is associated with a post-operative morbidity of 17.3% and mortality of 0.4%, with surgical site infections (SSI) accounting for about 5% of overall post-operative morbidity.3 The risk factors associated with wound complications include patient factors such as diabetes, smoking, obesity, immunosuppression and technical factors including wound closure techniques.4 A near-complete closure with a purse-string suture closure (PSC), as compared to linear primary closure (LPC), has been shown in three meta-analyses to have a significantly lower risk of SSI, but a longer healing time and a potentially worse cosmetic scar.5-8

Negative pressure, wound therapy (NPWT) was initially developed for use in 1997 for the treatment of open abdominal and complex trauma wounds.9 This wound management system consists of an open-cell foam or gauze dressing covered with an adhesive drape that is connected via suction tubing to a vacuum pump that creates a sub-atmospheric pressure. NPWT has been shown effective in reducing rates of SSI and has shown superiority over simple wound dressings in reducing wound healing times.10, 11 This reduction in time to wound healing is thought to be due to creation of a moist environment, less tissue oedema and stimulation of angiogenesis and granulation.12, 13

The SNaP™ (Smart Negative Pressure) wound care system (Spiracur, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA), an alternative traditional Vacuum-Assisted Closure (VAC) therapy, has shown to be non-inferior in terms of wound healing.14 It is a single-patient use, ultra-portable, lightweight unit, and it does not require recharging or batteries.15 It utilizes specialized springs to generate a continuous sub-atmospheric pressure level to the wound bed.16 This is in contrast with traditional electrically powered systems, which are limited by size and bulk, noise generated from the machine, battery replacement, costs and potentially lengthier dressing placement times. In reported case series patients using SNaP™ reported high levels of device-related satisfaction in addition to efficacy in decreasing wound area and exudate levels.17 In a cost analysis of diabetic lower extremity wounds, SNaP™ saved over $9000 per wound over standard dressings and $2300 per wound over electrically-powered NPWT.18

There are very few studies reporting on the efficacy of NPWT on wound healing compared with simple dressings, in patients where the ileostomy site is closed with a PSC.19, 20 This randomized controlled trial (RCT) was designed to determine whether the application of a mechanically-powered NPWT (SNap™ Therapy System) to wounds specifically following PSC of an ileostomy site, resulted in a clinically significant improvement in the rate of wound healing, compared to simple wound dressings. The primary endpoint was wound healing as defined by the proportion of patients achieving complete epithelialization at 42 days (6 weeks) post stoma closure. The depth of the wound was also measured at two time periods post-reversal. The secondary endpoints of the study were assessment of patient-reported scar cosmesis and surgical site infection rate.

Methods

Study setting and design

This was a dual centre, open-label, RCT with two parallel intervention arms. Sequential patients undergoing elective loop ileostomy reversal were randomized 1:1 to receive NPWT or simple wound dressings. Neither the participants nor the clinicians who administered the intervention were blinded to the treatment arm; however, the surgeons involved in the closure of the stoma site were blinded up to the point the purse string closure was performed. The study was undertaken at St Vincent's Public and Private Hospitals, Fitzroy. Five colorectal surgeons operating across both institutions participated. The study was conducted from June 2018 to December 2021. The trial was approved by the local ethical committee (HREC 18/SVHM/18).

Trial participants

Recruitment

Participants were recruited by the treating surgeon or another member of the colorectal unit, prior to their surgery. Written information pertaining to the trial was provided to participants at the time of the consent for their procedure.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All consenting patients over the age of 18 presenting for elective ileostomy closure were screened for eligibility and enrolled after informed consent was obtained. All indications for initial stoma creation (malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease or iatrogenic) were included. Participants in whom stoma closure was part of an emergency operation or involved a concomitant laparotomy were excluded from the study; the reason being because wound-specific quality of life measures would be uninterpretable in the context of a co-existing laparotomy wound.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoints included

- The rate of wound healing at day 42, defined as complete wound epithelialization with no discharge within a 24-h period.

- The percentage decrease in the depth of wound (measured from skin level to fascia, in millimetres), compared from intra-operative to 7th and 14th post-operative day.

The secondary endpoints included

- Wound cosmesis defined by a patient reported visual analogue score (VAS) for scar at day 42 post-reversal.

- Rate of surgical site infection.

Randomization

A one-to-one randomization was achieved using a computer-generated randomization sequence, stratified by site; this information was conveyed by a sealed envelope that was opened at the time of the surgery. The operating surgeons were blinded to the randomization outcome at the time of closure. The simple dressing or NPWT therapy was applied by the trial investigator under sterile conditions at the completion of the case.

Sample size

An initial power calculation indicated that a sample size of 16 in each group was required to detect a significant difference of 20% in rates of complete wound healing between simple wound dressings and NPWT, with a power of 0.8, standard deviation of 14, alpha level of 0.05 and sampling ratio of 1. We aimed to recruit 20 participants in each arm to account for patients who might withdraw from the study and potential exclusions.

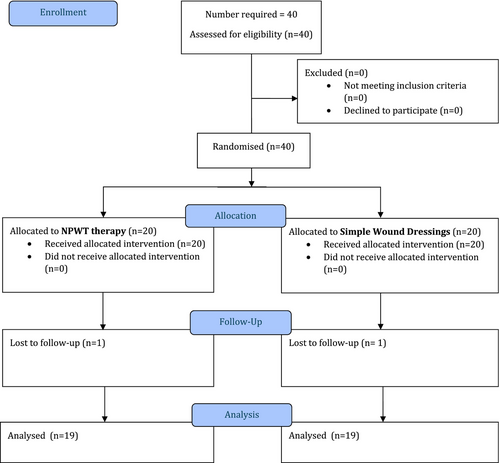

Study procedures and data collection

The study procedure is detailed in Figure 1. After the patients were screened for eligibility and informed consent obtained, baseline demographic and clinical data were prospectively recorded. Patients were then randomized to either intervention arm. Details of the surgical procedure and post-operative course were recorded during their hospitalization.

Perioperative care

Interventions

The patients were managed using enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols in the perioperative period. Prophylactic intravenous cefazolin and metronidazole were administered for all participants with no further post-operative prophylactic antibiotics. The skin incision was circumstomal, with a small skin cuff to facilitate retraction (<3 mm). Dissection was performed to completely mobilize the proximal and distal bowel limbs. The bowel anastomosis technique was performed based on surgeon preference, either by a stapled side-to-side or handsewn end-to-end technique. The fascia was closed with interrupted polydioxanone sutures. All participants, regardless of the primary surgeon, had their skin closure performed with a PSC in a standardized fashion. Prior to skin closure, the diameter of the wound in its longest dimension was measured. Skin edges were approximated with a continuous, near complete PSC using 3–0 poliglecaprone 25 (Fig. 2). The wound was narrowed around a suction tubing placed in the wound to create a standardized defect size. A depth measurement from the skin to the fascia in the centre of the wound, was taken prior to dressing placement.

The participants in the NPWT group had a 10 × 10 cm gauze interface wick dressing inserted into the wound (cut into a 2.5 cm width strip, with a length measured at 4 times the depth of the wound), followed by a hydrocolloid dressing that was connected via tubing to a 125 mmHg pressure, 60 mL cartridge. The NPWT dressing was left in situ until the third post-operative day, whereby it was changed by ward nursing staff as an inpatient. The dressing was completely removed and discarded on the seventh post-operative day in either an inpatient or outpatient setting. If participants were ready for discharge prior to the seventh post-operative day, they were not discharged with any hospital in the home or district nursing service. However, they were given some written information and ward contact details if there were dressing issues.

The participants in the control arm had a simple, non-woven, absorbent cotton dressing applied to the wound, with no further dressings inserted into the wound. These absorbent dressings were changed daily (or more frequently if exudate was significant) until complete epithelialisation was achieved.

Follow-up

Initial follow-up was carried out on the seventh post-operative day, which occurred as either an inpatient or outpatient. On that appointment, healing of the wound was assessed and the depth from skin to fascia measured. Following day seven review participants were required to take a photo of their wound and email this to a member of the research team to a common email address on a second-daily basis until complete epithelialisation occurred (Fig. 2). Visual analogue scale cosmesis scores were completed by the patient on day 14 and 42 post-reversal.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and aetiology were measured in frequencies and percentages. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using the chi-square test and student t-test respectively. Analysis of variance was calculated given the unbalanced distribution of VAS scores between the two groups All analysis was performed using the SPSS version 24 (Microsoft).

Results

Patients

A total of 40 patients were enrolled in the study period between June 2018 and December 2021. After randomization, 20 patients were allocated to undergo the NPWT and 20 patients in the control arm with simple wound dressings. One patient was lost to follow up from each group leaving 19 patients in each intervention arm. These were followed for the study period. There were no wound related complications during the study period.

Baseline characteristics and clinical features were similar in both groups. There were an equal number of males and females in each group. The mean age of the subjects in the control arm was 62 ± 15.1, and in the NPWT group was 55.67 ± 17.1 years (t(38) = 1.723, P = 0.093). All study patients were in the overweight BMI (body mass index) range. The mean BMI of the control group was 26.12 kg/m2 ± 4.50 and 27.62 kg/m2 ± 6.21 (t(30) = −0.78, P = 0.441) in the NPWT therapy arm. Most of the patients had stoma formation following bowel resection for malignancy, 14/19 patients in the simple dressings arm compared with 11/19 in the NPWT arm. There were eight patients undergoing diversion for inflammatory bowel disease in the NPWT arm compared with five in the simple dressing arm. There was one patient in each group who had a stoma formed in the setting of a diverticular resection.

Wound related outcomes

A total of 19/20 patients in each group were assessed at day 42 to determine if their wound had completely healed. Nine patients (9/19, 47.36%) in the standard dressing had healed vs. 13 patients (13/19, 68.42%) in the NPWT group. This difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 1.72, P value = 0.188).

When assessing the percentage reduction in the depth of the wound, only those patients where the defect in the skin had not yet closed could be assessed. In those that had wound depth measured, there was a greater mean reduction in wound depth in the standard dressing group at both day 7 (44 vs. 38%) and day 14 (75 vs. 50%).

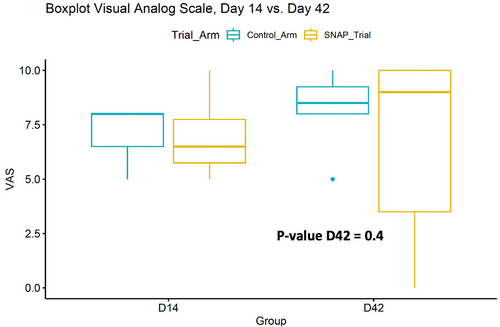

Cosmesis related outcomes

Patient-reported cosmesis was assessed using a VAS. A type III. There was no difference between the NPWT and simple dressing (F = 0.815, P = 0.4) (Fig. 3).

Surgical site infection

There were no surgical site infections identified in either group for the study period.

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, the efficacy NPWT in promoting wound healing was compared with simple dressings after elective loop ileostomy reversal with purse-string closure. Our study observed that there was a greater proportion of patients with healed stoma closure wound sites at day 42 in the NPWT group compared with simple dressing arm (68.4% vs. 47.4%), however the result was not statistically significant (P = 0.188). Additionally, there was no significant difference in patient-reported cosmesis of the wound using a visual analogue scale. Within our cohort there were no SSI identified in either group.

Other studies assessing the benefits of NPWT in the setting of stoma closure, focus on complication rates including SSI, seroma, and hematoma as well as patient length of stay (LOS). Surgical site infection rates with NPWT compared with simple dressings following stoma reversal are inconsistent. Two meta-analyses by Zhu (9 studies, n = 825) and Suheb et al. (unpublished, 10 studies, n = 1097) showed reduced SSI rates (OR = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.29, 0.84; P = 0.01) and no difference respectively (RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.37–1.10, P = 0.11).19, 20 Rates of seroma, hematoma and LOS were not different between groups within these two studies. Studies included in these meta-analyses were heterogenous in the type of stoma (colostomy vs. ileostomy) and configuration (end vs. loop), indication for stoma, skin closure technique and material used (PSC vs. LSC, sutures vs. staples), wound apertures of PSC, NPWT systems and their settings, simple dressings, definitions of SSI and peri-operative antibiotic usage. These meta-analyses did not compare healing rates, time to healing, cosmetic outcomes, patient satisfaction or cost between NPWT and simple dressings.

The pool of trials directly comparing wound healing with NPWT vs. simple dressings following closure of stoma sites with PSC is much smaller, with only four published studies (Table 1).21-24 Rates of SSI in all four studies did not show statistical significance between groups. Two of the studies reported on the proportion of wounds that had healed, and the other two time to wound healing. There was no significant difference seen between NPWT and simple dressings for either of these outcomes, consistent with our study results. There was still heterogeneity of stoma type and configuration, with studies by Kang and Carrano et al. including colostomies and ileostomies, either loop or end.21, 23 In the case of Hartmann's reversal, a concurrent laparotomy wound is required in a significant number of patients, which may affect patients return to bowel function, nutrition, and wound healing. The study by Uchino et al. only included patients who had previously had creation of a J-pouch and all patients were given bowel prep and oral antibiotics prior to stoma closure.22 Only one study by Kojima et al. had patients within the overweight BMI range and excluded patients with characteristics that may affect wound healing.24 Two out of the 4 studies assessed on patient-reported cosmesis, which was more acceptable in the NPWT group in a single study.21, 23

| Study, year | n, I/C | Wound aperture (mm) | Simple dressing | Duration of dressings | SSI rate (P) | Wound healing time (days), I/C (P) | Wound healed %, I/C (P) | Patient cosmesis score D30 | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kang et al. 202323 | 18/16 | ≤5 | Foam dressing | Until wound healed Twice weekly change |

ND (0.471) | Reduced in NPWT (0.006) | NR | ND (0.742) at | ND (0.365) |

| Carrano et al. 202121 | 49/48 | 8 (over suction tubing) | Saline irrigation | 7D | ND (1.000) | NR | ND (0.081) | Improved NPWT (0.003) | NR |

| Kojima 202124 | 10/10/10 | 15 (over syringe) | Gauze | 7D or 14D Initial change after 3D | ND (0.507) | ND I/C (7 days) (0.2448) I/C (24 days) (0.2946) |

NR | NR | NR |

| Uchino 201622 | 28/31 | 8 (over suction tubing) | Simple adhesive plaster | 14D Change every 3–4 days | ND (0.76) | NR | ND (0.18) | NR | NR |

- D, day; I/C, interventional arm/ control arm; mm, millimetre; n, number of patients; ND, no statistical difference; NPWT, negative pressure wound therapy; NR, not recorded.

Our study is limited by low numbers, and no adjustment for potential confounders. Additionally, wound evaluation was subjective and not blinded. There were no SSI detected in either group, however rates of seroma or hematoma formation were not assessed. The follow up period did not allow assessment of long-term complications such hernia. Finally, there was no formal cost comparison of the two study arms. Wound management present a significant cost to the health care system. In Australia it is estimated at 2% of national health care expenditure.25 The NPWT cost was $260 AUD (Australian dollars) for 7 days in our study. It is difficult to estimate the exact cost of the control arm, as simple dressings were used at variable frequency which was not recorded. Kang et al. showed no difference in cost between the NPWT and control group (P = 0.365).23 In their study an occlusive foam dressing was used as the simple dressing. A non-woven, cotton dressing was used in our study which is considerably cheaper than the foam dressing.

Conclusion

There was no significant difference in wound healing rates when comparing NPWT to simple wound dressings at both early and late time points post elective reversal of loop ileostomy, where the skin was closed with a purse-string closure. Additionally, there was no difference in patient-reported cosmesis in this study. Given the findings of this study, it would be important to formally assess financial and environmental cost differences in future studies prior to wide-spread adoption of NPWT in this clinical setting. There may be specific patient groups that may benefit from NPWT not identified in this study.

Funding information

This funding from Wounds Australia to cover NPWT costs.

Acknowledgement

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley - The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Author contributions

Thomas Tiang: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; project administration; writing – original draft. Corina Behrenbruch: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Jawed Noori: Writing – original draft. Madhu Bhamidipaty: Data curation; methodology. David Lam: Data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; methodology; project administration. Michael Johnston: Conceptualization; supervision. Rodney Woods: Conceptualization; project administration; supervision. Basil D'Souza: Conceptualization; project administration; supervision.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.