Comparative effectiveness of anti-IL5 and anti-IgE biologic classes in patients with severe asthma eligible for both

Abstract

Background

Patients with severe asthma may present with characteristics representing overlapping phenotypes, making them eligible for more than one class of biologic. Our aim was to describe the profile of adult patients with severe asthma eligible for both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R and to compare the effectiveness of both classes of treatment in real life.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study that included adult patients with severe asthma from 22 countries enrolled into the International Severe Asthma registry (ISAR) who were eligible for both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R. The effectiveness of anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R was compared in a 1:1 matched cohort. Exacerbation rate was the primary effectiveness endpoint. Secondary endpoints included long-term-oral corticosteroid (LTOCS) use, asthma-related emergency room (ER) attendance, and hospital admissions.

Results

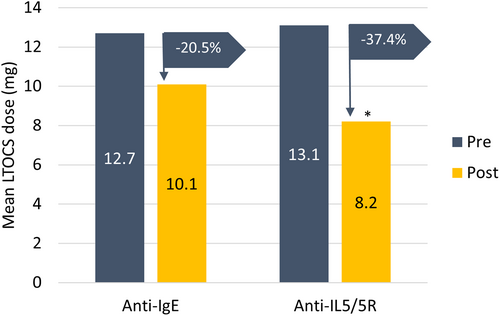

In the matched analysis (n = 350/group), the mean annualized exacerbation rate decreased by 47.1% in the anti-IL5/5R group and 38.7% in the anti-IgE group. Patients treated with anti-IL5/5R were less likely to experience a future exacerbation (adjusted IRR 0.76; 95% CI 0.64, 0.89; p < 0.001) and experienced a greater reduction in mean LTOCS dose than those treated with anti-IgE (37.44% vs. 20.55% reduction; p = 0.023). There was some evidence to suggest that patients treated with anti-IL5/5R experienced fewer asthma-related hospitalizations (IRR 0.64; 95% CI 0.38, 1.08), but not ER visits (IRR 0.94, 95% CI 0.61, 1.43).

Conclusions

In real life, both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R improve asthma outcomes in patients eligible for both biologic classes; however, anti-IL5/5R was superior in terms of reducing asthma exacerbations and LTOCS use.

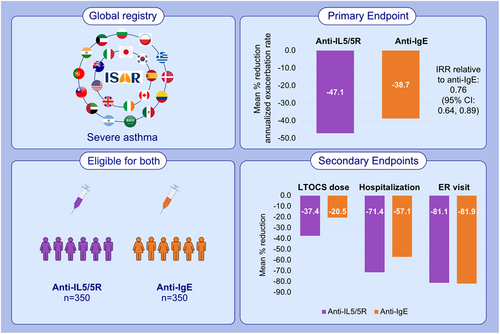

Graphical Abstract

The effectiveness of anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R was compared in this prospective cohort study including patients with severe asthma enrolled in ISAR and eligible for both biologic classes. Both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R improved asthma outcomes; however, anti-IL5/5R was superior in reducing asthma exacerbations and LTOCS use. These findings may be useful in assisting treatment decisions for patients with severe asthma.Abbreviations: Anti-IgE, anti-immunoglobulin E; Anti-IL5/5R, anti-interleukin 5/5R; CI, confidence interval; ER, emergency room; IRR, incidence rate ratio; ISAR, International Severe Asthma Registry; LTOCS, long-term oral corticosteroid

Abbreviations

-

- Anti-IgE

-

- anti-immunoglobulin E

-

- Anti-IL5/5R

-

- anti-interleukin 5/5R

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- ER

-

- emergency room

-

- IRR

-

- incidence rate ratio

-

- ISAR

-

- International Severe Asthma Registry

-

- LTOCS

-

- long-term oral corticosteroid

1 INTRODUCTION

Improved knowledge about the underlying pathogenesis of asthma has paved the way for the development of biologics, a tailored approach for the subset of patients with severe asthma whose asthma remains uncontrolled on standard non-biologic therapy.1-3 Anti-immunoglobulin (Ig) E (omalizumab) was the first of these biologics and showed effectiveness in those with severe allergic asthma.2 However, with the knowledge that the eosinophil was a hallmark of allergic asthma,4 and that, at that time, eosinophilic asthma was thought to comprise approximately 50% of adult severe asthma,5 the biologic target shifted to interleukin (IL) 5/5R, known to be important for the development and maturation of eosinophils.6 Subsequently, benralizumab,7, 8 reslizumab,9, 10 and mepolizumab were developed.11, 12 This biologic class has become even more important with recent knowledge that the prevalence of the eosinophilic phenotype in severe asthma is higher than previously thought and could be greater than 80%.13 Furthermore, the effectiveness of anti-IL5/5R biologics is well established not only in patients with severe asthma, but also in those with other atopic diseases (e.g., atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic esophagitis).14

Biologics are now appearing in asthma guidelines as add-on treatment for patients with severe asthma, in preference to LTOCS in those who meet eligibility criteria.5, 15 While the specific eligibility criteria for anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R biologic classes differ between countries (and between payers), their criteria overlap in many areas, including exacerbation rates, IgE concentrations, and/or blood eosinophil count (BEC).5, 16, 17 In clinical practice, patients may present with characteristics representing overlapping phenotypes, making them eligible for both biologic classes.18 However, this overlap population is poorly described in the literature in terms of both size and clinical characteristics.

Information on the relative clinical effectiveness of these two biologic classes is also limited and conflicting. For example, a large systematic review found no difference in the comparative effectiveness and tolerability of either anti-IgE and an anti-IL5 biologic.19 On the contrary, a small multicenter (albeit open label) study of patients with severe asthma, who were eligible for both biologic classes, but not optimally controlled with anti-IgE, found that these patients experienced improvements in asthma control, health status, and exacerbation rates upon switching to anti-IL5/5R.20

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) has recognized an ‘urgent need for head-to-head comparisons of different biologics in patients eligible for more than one biologic’.15

The International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR; https://isaregistries.org) contains the data necessary to perform such a head-to-head comparison. ISAR is a multi-country, multicenter, observational epidemiologic data repository, containing retrospective and prospective standardized data on > 12,000 patients with severe asthma from 25 countries.21-23 The aims of this study were to characterize patients with severe asthma who were eligible for both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R biologic classes (prior to treatment), and to compare their real life effectiveness.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and data source

This study was designed, implemented, and reported in compliance with the European Network Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (ENCEPP) Code of Conduct (EMA 2014; EUPAS 38128), with all applicable local and international laws and regulation, and registered with ENCEPP (https://www.encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=38129). Governance was provided by The Anonymous Data Ethics Protocols and Transparency (ADEPT) committee (registration number: ADEPT0920). All data collection sites in ISAR have obtained regulatory agreement in compliance with specific data transfer laws, country-specific legislation, and relevant ethical boards and organizations. The ISAR database has ethical approval from ADEPT (ADEPT0218) and is registered with the European Union Electronic Register of Post-Authorization studies (ENCEPP/DSPP/23720).

This was a cohort study which included adult patients with severe asthma enrolled in ISAR from September 2015 to October 2021. Prospective, de-identified patient data incorporating standardized variables from new and pre-existing severe asthma registries were pooled from 22 countries (Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, India, Italy, Japan, Kuwait, Mexico, Poland, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, United Arab Emirates, UK, and USA).

2.2 Objectives

The objectives of this study were twofold. Firstly, to describe the demographic and clinical features of the severe asthma population in ISAR, who were eligible for both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R at or before the date of starting therapy, and secondly, to compare the effectiveness of initiating anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R treatment in a matched cohort of patients eligible for both biologic classes.

2.3 Patients

Patients were required to be aged ≥18 years at enrolment and have severe asthma (i.e., receiving treatment at GINA 2020 Step 5 or with uncontrolled asthma at GINA Step 4).24 A summary of how each registry diagnoses asthma and categorizes severe asthma is provided in Appendix S1. Patients were also required to be eligible for both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R, with a minimum of 1-year longitudinal data prior to therapy. To be included in the comparative assessment analysis, patients were also required to subsequently receive one of these biologic classes (initially prescribed no earlier than January 01, 2014, when both biologic classes were available in all countries included in this study) and have 24 weeks continuous data post-biologic initiation. A patient was considered eligible for both biologic classes if they had an allergic phenotype defined by a positive skin prick or specific IgE test to perennial environmental aeroallergens, or, in the absence of these tests, had atopic asthma (allergic rhinitis or atopic), had a pre-therapy total serum IgE ≥30 IU/mL and a pre-therapy BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL (or ≥ 150 cells/μL for long-term oral corticosteroid (LTOCS) users), and had experienced ≥2 exacerbations in the last year or be on LTOCS. These biologic eligibility criteria were based on survey data from 28 ISAR contributing countries, taking into account the large international variation in country-specific criteria.17 Assumptions made about eligibility criteria are based on ISAR consensus work and are provided in Appendix S1. Patients who had received bronchial thermoplasty or who had a previous history of biologic use before enrollment in ISAR were excluded.

2.4 Variables collected

A full description of variables collected is provided in Appendix S1.

2.5 Outcomes and endpoints

The primary endpoint was annualized rate of severe asthma exacerbations in the year after biologic initiation. A severe exacerbation was defined as an asthma-related hospital attendance/admission and/or an asthma-related emergency room (ER) attendance, and/or an acute oral corticosteroid (OCS) course of ≥3 days. Exacerbations recorded within 14 days of each other were considered the same exacerbation. Secondary endpoints included LTOCS use (dose and duration) and number of ER visits, hospital admissions and invasive ventilations for asthma. LTOCS was defined as OCS therapy for at least 3 months.

2.6 Statistical analyses

The statistical analysis plan was pre-defined to meet standards of analysis. Stata version 14.2 (College Station) or SAS version 9.4/9.5 (Cary) were used to conduct all statistical analyses.

2.6.1 Selection of analysis population

We selected patients eligible for both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R, who subsequently received a biologic in either class post-2014, and who had at least 1 year of pre-biologic initiation information, at least 24 weeks of follow-up data, and both pre-and post-biologic initiation exacerbation data. The date from which effectiveness was compared was the day of biologic initiation for new biologic users or the day of ISAR enrolment for the non-biologic users.

2.6.2 Comparison of baseline characteristics (unmatched cohort)

Descriptive statistics were computed for all demographic and clinical characteristics in the form of continuous variables or categorical measures as appropriate. We compared baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and tested for difference by chi-square tests for comparison of counts data and t-test, or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. A standardized mean difference ≥ 10% indicated a clinically meaningful difference.

2.6.3 Comparative effectiveness analyses (matched cohort)

In the main analysis, of those eligible for both biologic classes, patients who initiated anti-IL5/5R were matched (1:1) to those who initiated anti-IgE by age group, gender, and LTOCS use. A post hoc sensitivity analysis was also performed using a 1 anti-IgE: 2 anti-IL5/5R matching ratio. Switchers (i.e., those who received >1 biologic during follow-up) were censored at the time of switch and were excluded from this analysis if they did not have 24 weeks of follow-up with the initiation biologic.

Exacerbation rate (mean total exacerbations per year and % patients with 0, 1,2, etc.), ER attendance, hospitalizations, and invasive ventilations (mean number in the past 12 months and % patients who experienced 1, 2, and 3 of these events) and LTOCS use (dose, % patients who stopped OCS, % who stopped or achieved a daily dose of <5 mg daily prednisolone equivalent) were described pre-and post-biologic therapy. In the matched analysis, exacerbations, hospitalizations, and ER attendance were compared using a Poisson regression to calculate crude incidence rate ratios (IRRs). These crude IRRs were further adjusted for pre-therapy exacerbation rate, asthma-related ER visits, hospitalizations, and invasive ventilations, BMI and pre-therapy asthma control to calculate adjusted IRRs, 95% confidence intervals and p values. A t-test was used to compare LTOCS dose between groups based on patients who had both pre-therapy and post-therapy doses for overall LTOCS.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Subject disposition

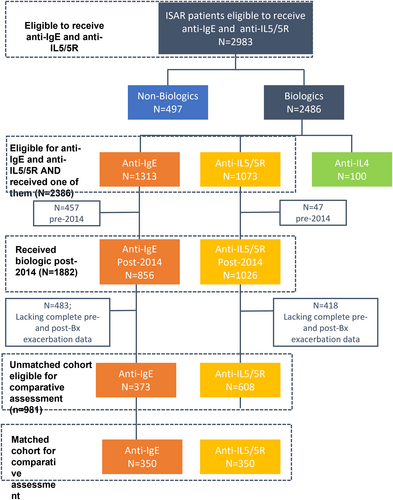

At baseline, 2983 patients were eligible for both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R therapy, of whom 2386 patients subsequently initiated either anti-IgE or anti-IL5/5R, 1882 of them post-2014 (Figure 1). Overall, 981 of these patients had pre-and post-biologic initiation exacerbation data and were eligible for the comparative effectiveness assessment, which was performed on a matched cohort of patients (n = 350 per group) (Figure 1). Data availability per country is provided in the online supplement, per biologic and per analysis eligibility criteria (Appendix S1).

3.2 Baseline characteristics (pre-treatment)

All patients eligible for anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R and who subsequently received one of them (n = 2386).

These data are provided in Appendix S1.

3.2.1 Unmatched cohort, eligible for comparative assessment (n = 981; anti-IgE: n = 373; anti-IL5/5R: n = 608)

Compared to patients who subsequently started anti-IgE therapy, those subsequently treated with anti-IL5/5R (mepolizumab: 78.8%, benralizumab: 17.6%, reslizumab: 3.1%, and unknown: 0.5%) tended to have later asthma onset (24.6 vs 30.1 years) and were older at biologic initiation (Table 1). Although the proportion of patients with uncontrolled asthma and the exacerbation frequency pattern were similar between groups at baseline, anti-IL5/5R initiators were more likely to be LTOCS users at baseline, with 46.7% of them on LTOCS compared with 32.2% of patients who subsequently received anti-IgE (Table 1).

| Anti-IgE (n = 373) | Anti-IL5 (n = 608) | p-value (SMD) | Anti-IgE (n = 350) | Anti-IL5 (n = 350) | p-value (SMD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmatched* | Matched (1:1)+ | |||||

| Age at biologic initiation, years | N = 350 | N = 350 | ||||

| 18–42, n (%) | 114 (30.6) | 138 (22.7) | 104 (29.7) | 104 (29.7) | ||

| 42–53, n (%) | 119 (31.0) | 157 (25.8) | <0.001 (−0.283) | 106 (30.3) | 106 (30.3) | NA |

| 54–63, n (%) | 79 (21.2) | 161 (26.5) | 79 (22.6) | 79 (22.6) | ||

| > 64, n (%) | 61 (16.4) | 152 (25.0) | 61 (17.4) | 61 (17.4) | ||

| Age of onset of asthma, years | N = 271 | N = 449 | N = 258 | N = 257 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 24.6 (17.9) | 30.1 (18.5) | <0.001 (−0.303) | 24.7 (18.2) | 27.7 (17.1) | 0.06 (−0.181) |

| BMI at biologic initiation | N = 292 | N = 483 | N = 274 | N = 271 | ||

| mean (SD) | 30.0 (7.1) | 28.8 (6.3) | 0.019 (0.172) | 30.0 (7.2) | 28.8 (6.6) | 0.04 (0.132) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female, N (%) | 234 (62.7) | 339 (55.8) | 0.031 (0.142) | 216 (61.7) | 216 (61.7) | NA |

| Asthma control at biologic initiation | N = 228 | N = 357 | N = 213 | N = 192 | ||

| Not controlled, n (%) | 173 (75.9) | 270 (75.6) | 0.05 | 163 (76.5) | 150 (78.1) | 0.004 |

| Partially controlled, n (%) | 27 (11.8) | 62 (17.4) | (−0.0715) | 25 (11.7) | 35 (18.2) | (−0.0617) |

| Well controlled, n (%) | 28 (12.3) | 25 (7.0) | 25 (11.7) | 7 (3.7) | ||

| Smoking status | N = 292 | N = 495 | N = 273 | N = 280 | ||

| Current, n (%) | 9 (3.1) | 8 (1.6) | 0.069 | 9 (3.3) | 4 (1.4) | 0.290 |

| Ex, n (%) | 77 (26.4) | 164 (33.1) | (0.0732) | 74 (27.1) | 84 (30.0) | (0.0395) |

| Never, n (%) | 206 (70.6) | 323 (65.3) | 190 (69.6) | 192 (68.6) | ||

| Pre-therapy exacerbation | N = 373 | N = 608 | N = 350 | N = 350 | ||

| 0, n (%) | 41 (11.0) | 70 (11.5) | 40 (11.4) | 37 (10.6) | ||

| 1, n (%) | 62 (16.6) | 88 (14.5) | 0.567 | 57 (16.3) | 53 (15.1) | |

| 2, n (%) | 60 (16.1) | 99 (16.3) | (0.0118) | 52 (14.8) | 60 (17.1) | 0.371 |

| 3, n (%) | 32 (8.6) | 70 (11.5) | 30 (8.6) | 46 (13.1) | (−0.0769) | |

| 4, n (%) | 41 (11.0) | 77 (12.7) | 40 (11.4) | 40 (11.4) | ||

| ≥ 5, n (%) | 137 (36.7) | 204 (33.6) | 131 (37.4) | 114 (32.6) | ||

| Receiving LTOCS, n (%) | 120 (32.2) | 284 (46.7) | <0.001 (−0.300) | 120 (34.3) | 120 (34.3) | NA |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IL-5/5R, interleukin 5/5 receptor; LTOCS, long-term oral corticosteroid; NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation.

- Note: * The unmatched group shows the population who have started their respective therapy from 2014 onwards, who have both pre-and post-biologic initiation exacerbation data. +The matched group shows those who have both pre-and post-biologic initiation exacerbation data and can be matched for LTOCS use, gender, and age.

3.2.2 Matched cohort (1:1), eligible for comparative assessment (anti-IgE: n = 350; anti-IL5/5R: n = 350)

Patients were well-matched in terms age of at biologic initiation and asthma onset, BMI, gender, and smoking status (Table 1). The proportion of patients with uncontrolled asthma, ≥2 pre-therapy/exacerbations in the previous 12 months and who were on LTOCS were similar between groups (Table 1).

3.3 Comparative effectiveness (1:1 matched cohort)

3.3.1 Exacerbations

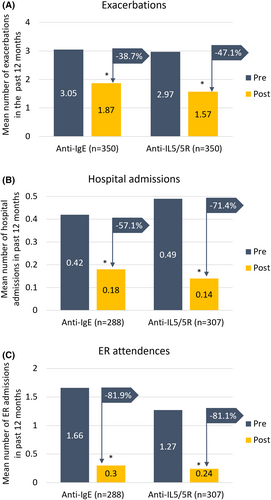

Patients treated with anti-IL5/5R had a 24% lower annualized rate of a future asthma exacerbation relative to those treated with anti-IgE (IRR 0.76; 95% CI 0.64, 0.89, p < 0.001) (Figure 2). See online supplement for unadjusted values (Appendix S1). The mean annualized exacerbation rate decreased in both groups but was more marked in the anti-IL5/5R cohort, reducing by 47.1% compared to by 38.7% for those in the anti-IgE group (Table 2; Figure 3A). In addition, the proportion of patients who experienced ≥3 exacerbations per year decreased from approximately 57% pre-treatment in both groups to 22.9% in the anti-IL5/5R group compared to 30.3% in the anti-IgE group (Table 2).

| Anti-IgE | Anti-IL5/5R | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Mean Difference (SD) and p-value | Pre | Post | Mean difference (SD) and p-value | |

| Exacerbations | N = 350 | N = 350 | N = 350 | N = 350 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.05 (1.86) | 1.87 (1.72) | 1.17 (1.99) | 2.97 (1.78) | 1.57 (1.64) | 1.44 (1.95) |

| 0, n (%) | 40 (11.4) | 89 (25.4) | p < 0.001 | 37 (10.6) | 116 (33.1) | p < 0.001 |

| 1, n (%) | 57 (16.3) | 97 (27.7) | 53 (15.1) | 95 (27.1) | ||

| 2, n (%) | 52 (14.8) | 58 (16.6) | 60 (17.1) | 59 (16.9) | ||

| 3, n (%) | 30 (8.6) | 36 (10.3) | 46 (13.1) | 23 (6.6) | ||

| 4, n (%) | 40 (11.4) | 17 (4.9) | 40 (11.4) | 19 (5.4) | ||

| ≥ 5, n (%) | 131 (37.4) | 53 (15.1) | 114 (32.6) | 38 (10.9) | ||

| Hospital admissions | N = 288 | N = 288 | N = 307 | N = 307 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.42 (1.60) | 0.18 (0.76) | 0.14 (0.75) | 0.49 (1.20) | 0.14 (0.76) | 0.27 (0.79) |

| 0, n (%) | 247 (85.8) | 262 (91.0) | 239 (77.9) | 282 (91.9) | ||

| 1, n (%) | 17 (5.9) | 16 (5.6) | p < 0.001 | 32 (10.4) | 20 (6.5) | p < 0.001 |

| 2, n (%) | 11 (3.8) | 4 (1.4) | 13 (4.2) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| ≥ 3, n (%) | 13 (4.5) | 6 (2.1) | 23 (7.5) | 3 (1.0) | ||

| ER admissions | N = 288 | N = 288 | N = 307 | N = 307 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.66 (4.50) | 0.30 (1.10) | 0.53 (1.20) | 1.27 (3.80) | 0.24 (1.00) | 0.32 (0.99) |

| 0, n (%) | 199 (69.1) | 241 (83.7) | 221 (72.0) | 271 (88.3) | ||

| 1, n (%) | 15 (5.2) | 34 (11.8) | p < 0.001 | 31 (10.1) | 23 (7.5) | p < 0.001 |

| 2, n (%) | 19 (6.6) | 5 (1.7) | 17 (5.5) | 6 (2.0) | ||

| ≥ 3, n (%) | 55 (19.1) | 8 (2.8) | 38 (12.4) | 7 (2.3) | ||

| Invasive ventilations | N = 288 | N = 288 | N = 307 | N = 307 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.06 (0.50) | 0.03 (0.06) | 0.042 (0.27) | 0.11 (0.80) | 0.03 (0.20) | 0.036 (0.35) |

| 0, n (%) | 277 (96.1) | 287 (99.7) | 291 (94.8) | 299 (97.4) | ||

| 1, n (%) | 9 (3.1) | 1 (0.3) | 9 (2.9) | 8 (2.6) | ||

| 2, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | p = 0.998 | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | p = 0.763 |

| ≥ 3, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

- Abbreviations: Anti-IgE, anti-immunoglobulin E (omalizumab); anti-IL5/5R, anti-interleukin 5/5 receptor (benralizumab, mepolizumab or reslizumab); ER, emergency room; ISAR, International Severe Asthma Registry; SD, standard deviation.

3.3.2 Asthma-related hospitalizations and ER admissions

There was some evidence to suggest that patients treated with anti-IL5/5R experienced less asthma-related hospitalization (IRR 0.64, 95% CI 0.38, 1.08), but not ER visits (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.61, 1.43) due to asthma relative to those treated with anti-IgE, (Figure 2). The mean hospitalization rate decreased in both groups, but this reduction was more marked in the anti-IL5/5R group, reducing by 71.4% compared to 57.1% in the anti-IgE group (Table 2, Figure 3B). ER attendance rates were reduced by about 81% in both groups (Figure 3C). Invasive ventilation numbers pre-and post-treatment were low in both groups.

3.3.3 LTOCS dose

The mean LTOCS dose reduced by 37.4% in the anti-IL5/5R compared with a 20.5% reduction in the anti-IgE group (p = 0.023) (Figure 4). Overall, 45.9% (n = 28/61) of patients on anti-IL5/5R had a LTOCS dose reduction compared to 30.6% (n = 15/49) of those on anti-IgE (p = 0.1042). In terms of extent of LTOCS dose reduction, 23.0% of anti-IL5/5R patents who reduced their LTOCS dose achieved a 50% to <75% LTOCS dose reduction compared to 14.3% of those who received anti-IgE. Furthermore, 26.2% of patients in the anti-IL5/5R group eliminated their LTOCS completely or achieved a daily dose of ≤5 mg compared with 16.3% of those in the anti-IgE group (p = 0.18).

3.4 Matching sensitivity analysis

Baseline and comparative effectiveness data for patients eligible for comparative assessment and matched 1:2 (anti-IgE (n = 373); anti-IL5/5R (n = 746)) confirmed our findings; those treated with anti-IL-5/5R had a lower rate of exacerbations (IRR 0.82; 95% CI 0.75, 0.90) and less asthma-related hospitalizations (IRR 0.68; 95% CI 0.42, 0.99).(Appendix S1)

4 DISCUSSION

Both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R were effective in reducing exacerbations, hospitalizations, and LTOCS use in this global, real life, severe asthma cohort, eligible for both biologics. However, anti-IL5/5R was more effective in this regard, even in comparison with a generally improving anti-IgE-treated cohort. Those treated with an anti-IL5/5R biologic had 24% and 36% lower rates of asthma exacerbation and hospitalizations for their asthma, respectively, compared to those treated with anti-IgE. More patients treated with anti-IL5/5R also had a LTOCS dose reduction compared to their anti-IgE counterparts (41.3% vs 25.9%; p = 0.014), while still experiencing a greater exacerbation rate reduction. These results are pertinent considering the high exacerbation burden (approximately 3 exacerbations/year) and high mean daily OCS dose (13.5 mg and 12.4 mg for patients subsequently treated with anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R, respectively) pre-therapy. The reductions noted here are also clinically relevant since the cost associated with managing exacerbations is high,25 and OCS use has been associated with considerable adverse effects, including osteoporosis, pneumonia, cataract, and cardiovascular disease.26

Interestingly, despite potentially overlapping clinical indications for these biologics, we found that anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R treated patients showed distinctive asthma phenotypes, pre-matching. Patients, who received anti-IL5/5R tended to have later onset disease, be older at biologic initiation and have a higher OCS burden (compared to anti-IgE patients). Others have confirmed phenotype-directed preferences for anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R prescription in real life.27, 28 Data from the UK severe asthma registry, for example, found that younger, atopic patients with an earlier disease onset were proportionately more likely to be prescribed anti-IgE, whereas a pattern of adult-onset, older patients with comorbid nasal polyposis and OCS use was noted in those who received anti-IL-5/5R.28 Data from the Wessex Asthma cohort of difficult asthma also reported a preponderance of older males, with late onset asthma and nasal polyposis in those who received mepolizumab versus omalizumab.27

The clinical utility of biologics for severe asthma has been demonstrated in multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs), with all biologics shown to reduce exacerbation rates compared with standard of care with a high certainty of evidence (benralizumab: IRR 0.53; dupilumab: 0.44; mepolizumab: 0.49; omalizumab: 0.56; and reslizumab: 0.46).29 However, these RCT populations are not reflective of real life, thought to represent <10% of patients with severe asthma by recent estimates30 and type 2 low asthma has been largely neglected, most likely due to the relatively low proportion of patients with severe asthma with this phenotype.13 Real-life studies have consistently shown better biologic-associated exacerbation rate reductions in the range of 72.8% for benralizumab,31 77.5% for mepolizumab,32 66.9% for reslizumab,33 and 73.2% for omalizumab.34 These exacerbation rate reductions are greater than those seen in our study (i.e., Anti-IL-5/5R: 47.1%; Anti-IgE: 38.7%), most likely due to differences in patient cohorts, exacerbation definitions, exacerbation rates at baseline and the presence of other confounding factors such as country, LTOCS use, and presence of nasal polyps. However, a recently published US claims database reporting a similar anti-IL5/5R-induced exacerbation rate reduction to that seen in our study (55%) found that this level of reduction is associated with a reduction in exacerbation-related costs per patient of USD $6439.35

The real-life effectiveness of biologics in improving other asthma outcomes is also well documented, most recently in a large global cohort of patients with severe asthma with high OCS exposure.36 In that study, biologic initiation was associated with an average reduction of 1.43 exacerbations relative to non-initiators after 1 year of treatment, but also an approximate halving of the risk and frequency of asthma-related ED visits and hospitalizations.36 Importantly, this superiority of biologics occurred compared to a high OCS exposure cohort with generally improving asthma control and in an environment of reduced OCS exposure in the biologic group. Indeed, biologic initiators were 2 times more likely to achieve a daily long-term OCS dose <5 mg and 4 times more likely to achieve a reduction in total OCS dose of 75–100% from baseline.36 The current study goes one step further, providing some evidence of superiority of one biologic class (anti-IL5/5R) over another (anti-IgE).

Comparing the efficacy of biologics for asthma is challenging as no direct head-to-head RCT comparisons have been published, and indirect comparisons have produced conflicting results.37, 38The most recently published indirect comparison of biologics found no clinically significant differences in RCT efficacy outcomes between dupilumab, mepolizumab, and omalizumab in patients aged >12 years with severe type 2 asthma characterized by eosinophilia and/or perennial allergy.38 However, the effectiveness of biologics in real life has recently been directly compared.39, 40 The first of these studies including a small population of Finnish patients with severe asthma provided some evidence of anti-IL5/5R superiority over anti-IgE for some asthma outcomes (albeit not in patients eligible for both classes).39 The authors found that patients treated with anti-IL5/5R experienced a significant reduction in mean daily OCS dose, an effect which was not seen in the anti-IgE group.39 Furthermore, although both anti-IL5/5R and anti-IgE significantly reduced the number of OCS courses and total number of exacerbations compared to baseline, these reductions were more apparent in the anti-IL5/5R group; 65.8% vs. 52.8% reduction for number of OCS courses and 58.5% vs. 32.1% reduction in total number of exacerbations.39 A more recent direct comparison of biologics found that mepolizumab, benralizumab, and omalizumab all had significant positive effects on symptom control but not lung function as measured by FEV1 and PEF in this cohort. While there were some minor differences in FEV1 and PEF responses between those taking mepolizumab and benralizumab and a tendency towards greater control of exacerbations in the benralizumab group, these observations did not reach statistical significance.40 However, others have reported biologic-associated improvement in lung function.41

Our study, including a matched cohort of 700 patients from 22 countries, found remarkably similar reductions in exacerbation rate and LTOCS dose, with anti-IL5-5R reducing mean exacerbation rate by 58.5% (vs. 32.1% for anti-IgE), and 51.7% of anti-IL5/5R patients completely eliminating LTOCS or reducing LTOCS daily dose to ≤5 mg (vs. 40.7% for anti-IgE). Others have found a greater LTOCS dose elimination or reduction potential with benralizumab than that reported here.42 The PONENTE study found that when using a personalized dosage reduction algorithm, over 80% of patients treated with benralizumab could eliminate or achieve a dosage of 5 mg or less,42 suggesting that a more aggressive and personalized LTOCS dose tapering schedule may be warranted in biologic treatment patients. The benefits of anti-IL5/5R over anti-IgE observed in our study and by others suggest the need to be more aggressive with biologic decisions and a greater readiness to consider switching if the desired or expected outcome is not achieved. Currently, switching biologics is not a common practice. A recently published study from ISAR found that 79% of biologic-treated patients continue with their first biologic; only 11% switched to an alternate; the most frequent first switch being from omalizumab to an anti–IL-5/5R the largest class which includes 3 biologics.43 Predictors of response to biologic classes are currently being investigated as part of the ISAR initiative.

Limitations include those common to observational studies such as missing data and recall bias. Reasons for choice of one class of biologic over another were also not collected, introducing the possibility of a phenotype selection bias, and criteria of eligibility were simplified to encompass eligibility for both biologic classes including a broad definition of allergic phenotype, defined as a positive skin prick or specific IgE test, but also, the presence of atopy and/or pre-therapy BEC cut-offs. More definitive evidence of allergy driven disease would have been preferable, but this is rarely collected in real life. Future work to assess the effectiveness of anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R in patients eligible for both according to age of asthma onset is planned. Additionally, the LTOCS dose reduction analysis was not adjusted by country which could have confounded results due to inter-country variability in steroid tapering schedules. Some of these limitations are mitigated by the rigor of our statistical analyses. For example, the matched design and analysis help ensure efficient adjustment for potential confounders. Effectiveness was also assessed post-2014 when both biologic classes were available in all countries included, and eligibility criteria for biologic assesses were based on a large biologic prescription criteria survey, which included 28 countries.17 Additional strengths of our study are its large size, incorporating a large, heterogeneous asthma cohort (n = 350 for comparative effectiveness assessment) from 22 countries, and generalizability of our findings to the global severe asthma population.

In real life, patients eligible for both anti-IgE and anti-IL5/5R who subsequently initiated anti-IL5/5R tended to have later onset asthma and a greater LTOCS exposure than their anti-IgE counterparts pre-treatment, and experienced a greater reduction in future exacerbations, and were more like to reduce their LTOCS dose on treatment in patients matched for phenotype characteristics. These findings may be useful in assisting treatment decisions for patients with severe asthma, and add to the growing body of robust real-life data on biologics, which provide insight not only on biologic effectiveness in real life and in different patient cohorts, but also on severe asthma itself. Adequately powered, randomized controlled head-to-head comparisons of biologics for severe type 2 asthma are required to confirm these findings. A study to directly compare omalizumab and mepolizumab is currently recruiting.44

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

David B. Price agrees to be accountable for all content and aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Nasloon Ali, Ruth Murray, Celine Goh, Juntao Lyu, Anthony Newell, and David B. Price had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were involved in data acquisition or analysis and interpretation, as well as the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study. All authors were responsible for drafting the manuscript. Nasloon Ali, Ruth Murray, Celine Goh, Juntao Lyu, Anthony Newell, and David B. Price provided additional administrative, technical, and material support. The study was supervised by Paul E. Pfeffer, Nasloon Ali, Ruth Murray, Charlotte Ulrik, Trung N. Tran, and David B. Price. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In memory of Professor J. Mark Fitzgerald, the authors would like to acknowledge him for his valuable contribution to the development of the manuscript. The authors also acknowledge Ms. Daniela Morrone (MSc) of Cromsource, Verona, Italy, for her contribution during the development of the manuscript and Mr. Joash Tan (BSc, Hons) of the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute (OPRI), for editorial and formatting assistance that supported the development of this publication.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was conducted by the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute (OPRI) Pte Ltd and was partially funded by Optimum Patient Care Global and AstraZeneca Ltd. No funding was received by the Observational & Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd (OPRI) for its contribution.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Paul E. Pfeffer has attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi; has given lectures at meetings supported by AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline; has taken part in clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Sanofi, for which his institution received remuneration; and has a current research grant funded by GlaxoSmithKline. Nasloon Ali was an employee of OPRI at the time this research was conducted. OPRI conducted this study in collaboration with Optimum Patient Care and AstraZeneca. Ruth B. Murray declares no relevant conflicts of interest. Charlotte Ulrik has attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca, ALK-Abello, GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Chiesi, TEVA,Covis Pharma, and Sanofi-Genzyme; has given lectures at meetings supported by AstraZeneca, Sandoz, Mundipharma, Chiesi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Orion Pharma, Novartis, TEVA, Sanofi-Genzyme, and GlaxoSmithKline; has taken part in clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, Novartis, Merck, InsMed, ALK-Abello, Sanofi-Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Regeneron, Chiesi, and Novartis; and has received educational and research grants from AstraZeneca, MundiPharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, TEVA, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi-Genzyme. Trung N. Tran is an employee of AstraZeneca; AstraZeneca is a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry. Jorge Maspero reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from IMMUNOTEK, personal fees from SANOFI, outside the submitted work. Matthew Peters declares personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline. George C. Christoff declares no relevant conflicts of interest. Mohsen Sadatsafavi has received honoraria from AZ, BI, TEVA, and GSK for purposes unrelated to the content of this manuscript and has received research funding from AZ and BI directly into his research account from AZ for unrelated projects. Carlos A. Torres-Duque has received fees as advisory board participant and/or speaker from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Sanofi-Aventis; has taken part in clinical trials from AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Sanofi-Aventis; has received unrestricted grants for investigator-initiated studies at Fundacion Neumologica Colombiana from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, and Novartis. Alan Altraja has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Norameda, Novartis, Sanofi, Zentiva, and Orion; sponsorships from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Norameda, Sanofi, and Novartis; and has been a member of advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva. Lauri Lehtimäki declares personal fees for consultancy, lectures and attending advisory boards from ALK, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Circassia, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, Novartis, Orion Pharma, Sanofi, and Teva. Nikolaos G. Papadopoulos declares research support from Gerolymatos, Menarini, Nutricia, and Vian; and consultancy/speaker fees from ASIT, AZ, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, HAL Allergy, Medscape, Menarini, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, and Nutricia, OM Pharma, Sanofi, and Takeda. Sundeep Salvi: declares research support and speaker fees from Cipla, Glenmark, GSK. Richard W. Costello has received honoraria for lectures from Aerogen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Teva. He is a member of advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis, has received grant support from GlaxoSmithKline and Aerogen and has patents in the use of acoustics in the diagnosis of lung disease, assessment of adherence and prediction of exacerbations. Breda Cushen has received honoraria for lectures from Astra Zeneca, Novartis, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Enrico Heffler participates in speaking activities and industry advisory committees for AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Genzyme, GSK, Novartis, TEVA, Circassia, and Nestlè Purina. Takashi Iwanaga declares grants from Astellas, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Kyorin, MeijiSeika Pharma, Teijin Pharma, Ono, and Taiho, and lecture fees from Kyorin, GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca. Mona Al-Ahmad has received advisory board and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline. Received a grant from Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS). Désirée Larenas Linnemann reports personal fees from Allakos, Amstrong, Astrazeneca, Bayer, Chiesi, DBV Technologies, Grunenthal, GSK, Mylan/Viatris, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Sanofi, Siegfried, UCB, Carnot, grants from Sanofi, Lilly, Pfizer, Abbvie, Astrazeneca, Novartis, Circassia, UCB, GSK, Purina institute, outside the submitted work. Piotr Kuna reports personal fees from Adamed, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Berlin Chemie Manarini, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Lekam, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from Polpharma, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Teva, personal fees from Zentiva, outside the submitted work. João A Fonseca reports grants from or research agreements with AstraZeneca, Mundipharma, Sanofi Regeneron and Novartis. Personal fees for lectures and attending advisory boards: AstraZeneca, GSK, Mundipharma, Novartis, Sanofi Regeneron, and TEVA. Riyad Al-Lehebi has given lectures at meetings supported by AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi, and participated in advisory board fees from GlaxoSmithKline. Chin Kook Rhee declares consultancy and lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, MSD, Novartis, Sandoz, Sanofi, Takeda, and Teva-Handok. Luis Perez-de-Llano declares non-financial support, personal fees, and grants from Teva; non-financial support and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Esteve, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, and Novartis; personal fees and grants from AstraZeneca and Chiesi; personal fees from Sanofi; and non-financial support from Menairi outside the submitted work. Diahn-Warng Perng (Steve) received sponsorship to attend or speak at international meetings, honoraria for lecturing or attending advisory boards, and research grants from the following companies: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo, Shionogi, and Orient Pharma. Bassam Mahboub reports no conflict of interest. Eileen Wang has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Wefight, and Clinical Care Options. She has been an investigator on studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Sanofi, Novartis, and Teva, for which her institution has received funding. Celine Goh is an employee of the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute OPRI. OPRI conducted this study in collaboration with Optimum Patient Care and AstraZeneca. Juntao Lyu is an employee of Optimum Patient Care (OPC), OPC a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry. Anthony Newell was an employee of OPC at the time this research was conducted, OPC a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry. Marianna Alacqua was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time this research was conducted. AstraZeneca is a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry. Andrey S. Belevskiy has received lecture grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi. Mohit Bhutani has received advisory board and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, and Covis pharmaceuticals; has been an investigator on clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Genzyme, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Leif Bjermer has (in the last 3 years) received lecture or advisory board fees from Alk-Abello, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, Novartis, Sanofi, Genzyme/Regeneron, and Teva. Unnur Bjornsdottir receives gratuities for lectures/presentations from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Novartis. Arnaud Bourdin has received industry-sponsored grants from AstraZeneca-MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cephalon/Teva, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi-Regeneron and consultancies with AstraZeneca-MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Regeneron-Sanofi, Med-in-Cell, Actelion, Merck, Roche, and Chiesi. Anna von Bülow reports speakers' fees and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis, outside the submitted work. She has also attended advisory board for Novartis and AstraZeneca. John Busby declares no relevant conflicts of interest. Giorgio Walter Canonica has received research grants, as well as lecture or advisory board fees from A. Menarini, Alk-Albello, Allergy Therapeutics, Anallergo, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Circassia, Danone, Faes, Genentech, Guidotti Malesci, GlaxoSmithKline, Hal Allergy, Merck, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Orion, Sanofi Aventis, Sanofi, Genzyme/Regeneron, Stallergenes, UCB Pharma, Uriach Pharma, Teva, Thermo Fisher, and Valeas. Borja G. Cosio declares grants from Chiesi and GSK; personal fees for advisory board activities from Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi and AstraZeneca; and payment for lectures/speaking engagements from Chiesi, Novartis, GSK, Menarini, and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. Del Dorscheid is supported by the following grants and clinical trials: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, British Columbia Lung Association, and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and AstraZeneca, Teva and Sanofi Regeneron. He has received speaking fees, travel grants, unrestricted project grants, writing fees and is a paid consultant via ad boards and other mechanisms for Sanofi Regeneron, Novartis Canada, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and ValeoPharma. Mariana Muñoz-Esquerre has attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca, ALK-Abello, GSK, Chiesi, TEVA, and Sanofi-Genzyme; has given lectures at meetings supported by AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Novartis, TEVA, Sanofi-Genzyme, Ferrer, and GlaxoSmithKline; has taken part in clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Regeneron, Palobiofarma, Chiesi, and Novartis; and has received educational and research grants from AstraZeneca, Novartis, ALK-Abello, TEVA, GlaxoSmithKline, Chiesi, and Sanofi-Genzyme. J. Mark FitzGerald reports grants from AstraZeneca, GSK, Sanofi Regeneron, Novartis paid directly to UBC. Personal fees for lectures and attending advisory boards: AstraZeneca, GSK, Sanofi Regeneron, TEVA. Peter G. Gibson has received speakers and grants to his institution from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis. Esther Garcia Gil was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time this research was conducted. AstraZeneca is a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry. Liam G. Heaney declares he has received grant funding, participated in advisory boards and given lectures at meetings supported by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Circassia, Evelo Biosciences, Hoffmann la Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Theravance, and Teva; he has taken part in asthma clinical trials sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffmann la Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline for which his institution received remuneration; he is the Academic Lead for the Medical Research Council Stratified Medicine UK Consortium in Severe Asthma which involves industrial partnerships with a number of pharmaceutical companies including Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann la Roche, and Janssen. Mark Hew declares grants and other advisory board fees (made to his institutional employer) from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi, and Seqirus, for unrelated projects. Ole Hilberg declares lecture and advisory board fees from GSK, AZ, BI, TEVA, Chiesi, Novatis, MSD, and Sanofi. Flavia Hoyte declares honoraria from AstraZeneca. She has been an investigator on clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Teva, and Sanofi, for which her institution has received funding. David J. Jackson has received advisory board and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Teva, Napp, Chiesi, Novartis and research grant funding from AstraZeneca. Mariko Siyue Koh reports grant support from AstraZeneca, and honoraria for lectures and advisory board meetings paid to her hospital (Singapore General Hospital) from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. Ko, Hsin-Kuo Bruce has received advisory board and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, and Novartis. Jae Ha Lee reports no conflict of interest. Sverre Lehmann declares receipt of lecture (personal) and advisory board (to employer) fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis. He has participated in research with AstraZeneca and GSK for which his institution has been remunerated. Cláudia Chaves Loureiro has received advisory board and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva, and research grant funding from GlaxoSmithKline. Dora Ludviksdottir reports no conflict of interest. Andrew N. Menzies-Gow has attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva, and has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Teva, and Sanofi. He has participated in research with AstraZeneca for which his institution has been remunerated and has attended international conferences with Teva. He has had consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca and Sanofi. Patrick Mitchell has received speaker fees from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Teva, and Novartis, and has received grants from AstraZeneca and Teva. Daniela Morrone declares no relevant conflicts of interest. Andriana I. Papaioannou has received fees and honoraria from Menarini, GSK, Novartis, Elpen, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and Chiesi. Todor A. Popov declares relevant research support from Novartis and Chiesi Pharma. Celeste M. Porsbjerg has attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Novartis, TEVA, and Sanofi-Genzyme; has given lectures at meetings supported by AstraZeneca, Novartis, TEVA, Sanofi-Genzyme, and GlaxoSmithKline; has taken part in clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, Novartis, MSD, Sanofi-Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis; and has received educational and research grants from AstraZeneca, Novartis, TEVA, GlaxoSmithKline, ALK, and Sanofi-Genzyme. Laila Salameh declares no relevant conflicts of interest. Concetta Sirena declares no relevant conflicts of interest. Camille Taillé has received lecture or advisory board fees and grants to her institution from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Chiesi, and Novartis, for unrelated projects. Christian Taube declares no relevant conflicts of interest. Yuji Tohda declares honoraria from Kyorin Pharma and Teijin Pharma, and research funding from Kyorin Pharma and Meiji Seika Pharma. Michael E. Wechsler reports grants and/or personal fees from Novartis, Sanofi, Regeneron, Genentech, Sentien, Restorbio, Equillium, Genzyme, Cohero Health, Teva, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Amgen, GlaxosmithKline, Cytoreason, Cerecor, Sound biologic, Incyte, Kinaset. David Price has advisory board membership with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Circassia, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Thermofisher; consultancy agreements with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Theravance; grants and unrestricted funding for investigator-initiated studies (conducted through Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd) from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Circassia, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Respiratory Effectiveness Group, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Theravance, UK National Health Service; payment for lectures/speaking engagements from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Kyorin, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals; payment for the development of educational materials from Mundipharma, Novartis; payment for travel/accommodation/meeting expenses from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mundipharma, Mylan, Novartis, Thermofisher; funding for patient enrolment or completion of research from Novartis; stock/stock options from AKL Research and Development Ltd which produces phytopharmaceuticals; owns 74% of the social enterprise Optimum Patient Care Ltd (Australia and UK) and 74% of Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd (Singapore); 5% shareholding in Timestamp which develops adherence monitoring technology; is peer reviewer for grant committees of the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme, and Health Technology Assessment; and was an expert witness for GlaxoSmithKline.