Acute and long-term management of food allergy: systematic review

Abstract

Background

Allergic reactions to food can have serious consequences. This systematic review summarizes evidence about the immediate management of reactions and longer-term approaches to minimize adverse impacts.

Methods

Seven bibliographic databases were searched from their inception to September 30, 2012, for systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, quasi-randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, controlled before-and-after and interrupted time series studies. Experts were consulted for additional studies. There was no language or geographic restrictions. Two reviewers critically appraised the studies using the appropriate tools. Data were not suitable for meta-analysis due to heterogeneity so were narratively synthesized.

Results

Eighty-four studies were included, but two-thirds were at high risk of potential bias. There was little evidence about acute management for non-life-threatening reactions. H1-antihistamines may be of benefit, but this evidence was in part derived from studies on those with cross-reactive birch pollen allergy. Regarding long-term management, avoiding the allergenic food or substituting an alternative was commonly recommended, but apart from for infants with cow's milk allergy, there was little high-quality research on this management approach. To reduce symptoms in children with cow's milk allergy, there was evidence to recommend alternatives such as extensively hydrolyzed formula. Supplements such as probiotics have not proved helpful, but allergen-specific immunotherapy may be disease modifying and therefore warrants further exploration.

Conclusions

Food allergy can be debilitating and affects a significant number of people. However, the evidence base about acute and longer-term management is weak and needs to be strengthened as a matter of priority.

Food allergy affects many millions of people and is responsible for substantial morbidity, impaired quality of life, and costs to the individual, family, and society 1. In some cases, it may prove fatal 2. Allergy may develop to almost any food, but is triggered most commonly by cow's milk, hen's eggs, wheat, soy, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, and seafood 3, 4. There are two main approaches to managing food allergy: those targeting immediate symptoms and those aiming to support longer-term management. This review summarizes research about strategies for the acute and long-term management of children and adults with IgE- and non-IgE-mediated food allergy.

The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) is developing EAACI Guidelines for Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis. This systematic review is one of seven interlinked syntheses undertaken to provide a state-of-the-art synopsis of the evidence base in relation to the epidemiology, prevention, diagnosis, management, and impact on quality of life, which will be used to inform clinical recommendations. The aims of the review were to examine what pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions have been researched to (i) manage immediate non-life-threatening symptoms of food allergy (i.e., acute treatment) and (ii) manage long-term symptoms and promote desensitization/tolerance (i.e., longer-term management).

Methods

Protocol and registration

The review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. The protocol has been published previously 5 so only brief details about the methodology are provided here.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched: Cochrane Library; MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, ISI Web of Science, TRIP Database and Clinicaltrials.gov. Experts in the field were contacted for additional studies. Further details are included in the review protocol 6.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies of children or adults diagnosed with food allergy or reporting that they had food allergy were included. This included allergy where food was the primary sensitizer and pollen-associated food allergy if there was a direct diagnosis of food allergy. Studies of interventions for life-threatening manifestations were excluded because they were the focus of another review in this series 7.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, quasi-randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, controlled before-and-after studies, and interrupted time series studies published up until September 30, 2012, were eligible. No language restrictions were applied and, where possible, relevant studies in languages other than English were translated.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts of articles were checked by two independent reviewers and categorized as included, not included and unsure (DdS and MG). Full-text copies of potentially relevant studies were obtained, and their eligibility for inclusion was independently assessed by two reviewers (DdS and MG). Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus or discussion with a third reviewer (AS).

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias was independently carried out by two reviewers (DdS and MG) using adapted versions of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool (http://www.casp-uk.net/) and the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of care Group (EPOC) Risk of Bias tools. An overall grading of high, medium, or low quality was assigned to each study.

Analysis, synthesis, and reporting

A customized data extraction form was used to abstract data from each study, this process being independently undertaken by two reviewers (DdS and MG). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Three experts in the field checked all of the data extraction for accuracy and relevance (AS, RvR, TW). Meta-analysis was not appropriate because the studies were heterogeneous in focus, design, target populations, and interventions. Findings were synthesized narratively by grouping studies according to topic, design, quality, and outcomes. The narrative synthesis was checked by a group of methodologists and subject experts to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

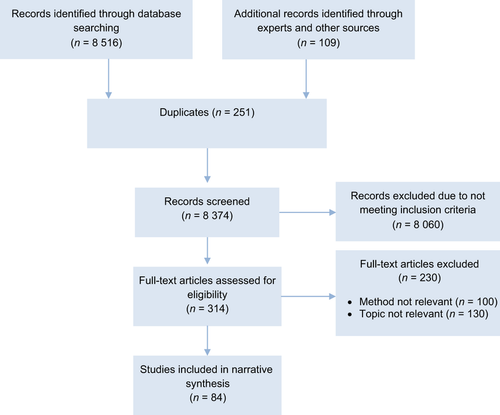

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart. Eighty-four studies were included, comprising 12 systematic reviews (15%), 54 randomized controlled trials (64%), and 18 nonrandomized comparative or controlled cross-over studies (21%). Based on the risk of bias assessment, nine of the studies were deemed to be of high quality (11%), 20 were of moderate quality (24%), and 55 were of low quality (65%), often due to small sample sizes. Further details about each study are available in the online Supporting Information.

Managing acute reactions

Table 1 lists the key findings.

| Intervention | Studies | % High quality | Overall findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies to treat acute symptoms | |||

| Antihistamines | 5 | 0 | Three randomized trials and two nonrandomized comparisons found that antihistamines may reduce immediate symptoms or severity in children and adults 8-12 |

| Long-term management strategies | |||

| Antihistamines | 1 | 0 | One trial found prophylactic antihistamines improved symptoms 22 |

| Mast cell stabilizers | 9 | 0 | Four randomized trials and two nonrandomized comparisons found that prophylactic mast cell stabilizers reduced symptoms or severity in children, adults, or both 13-18. Three randomized trials found no benefits. Side-effects were noted 19-21 |

| Other pharmacological treatments | 2 | 0 | One trial of calf thymus acid lysate derivative found improved skin lesions 23. One trial of a herbal treatment found no improvement in symptoms 24 |

| Dietary elimination | 4 | 0 | One trial and one nonrandomized comparison found that dietary elimination worked well for children allergic to cows' milk or eggs 41, 42, but a systematic review and a nonrandomized comparison suggested no benefits for spices or fruit allergies in children 43, 44. No relevant studies were identified in adults |

| Dietary substitution: cows' milk formula substitutes | 17 | 12 | One trial and one nonrandomized comparison found extensively hydrolyzed formulas to be well tolerated 25, 26. A systematic review and three randomized trials found that amino acid-based formulas were well tolerated and may reduce symptoms among infants with cows' milk allergy 27-30. A systematic review and a randomized controlled trial concluded that soy milk is nutritionally adequate and well tolerated 31, 32, but a randomized trial concluded that soy may be less well tolerated than extensively hydrolyzed whey formula 33. Two randomized controlled trials found that rice hydrolyzate formula was well tolerated 34, 35, but one randomized trial found no benefits 36. One randomized trial found that almond milk was well tolerated 37. Another randomized trial found that chicken-based formula was better tolerated than soy-based formula 38. A systematic review concluded that donkey or mare's milk was as allergenic as cows' milk 31, but a randomized trial suggested that donkey's milk was better tolerated than goat's milk 39. A nonrandom comparison found that meat-based formulas were well-tolerated and reduced symptoms in infants with other food allergies 40 |

| Probiotic supplements | 11 | 27 | One systematic review, three randomized trials, and one nonrandomized comparison found that probiotic supplements may reduce symptoms and support long-term tolerance in infants with cows' milk allergy or other allergies 45-49. Five randomized trials found no benefits in infants and one trial found no benefits in young adults 50-55. |

| Subcutaneous immunotherapy | 9 | 11 | Five randomized trials and four other studies found improved tolerability in children and adults 56-63. One trial found no benefits 64 |

| Sublingual immunotherapy | 5 | 0 | Four trials found that sublingual immunotherapy was associated with improved tolerability for those with peanut and fruit allergies 65-68. One trial found no benefit 69 |

| Oral immunotherapy | 18 | 22 | Two systematic reviews, nine randomized trials, and four nonrandomized comparisons found that oral immunotherapy was associated with improved tolerability for children and adults with various food allergies 70-83. One randomized trial found no benefit 84. Two systematic reviews found mixed evidence and concluded that oral immunotherapy should not be routine treatment 85, 86 |

People with food allergy are often advised to completely avoid allergenic foods, but this may not always be possible. Pharmacological treatments are available to help people manage the symptoms when they are exposed to food allergens. The most common class of drugs assessed for this purpose is H1-antihistamines, taken as required when symptoms occur.

Three randomized trials and two nonrandomized comparisons, all with methodological issues, suggested that H1-antihistamines may have some benefit, particularly in combination with other drugs 8-12. Some of the literature about H1-antihistamines focused on treating those with a primary birch pollen allergy and cross-reactive symptoms with biological-related foods (pollen-food syndrome), while other studies included people with a diverse range of disease manifestations. The safety profile of H1-antihistamines in people with food allergy was not well reported.

Other medications have been used in people with food allergy, but we failed to identify any studies investigating these medicines that fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Longer-term management

Pharmacological treatment

Pharmacological strategies for long-term management involve taking ongoing treatment to prevent symptoms from reappearing or worsening (as well as potentially treating existing manifestations).

There were mixed findings about mast cell stabilizers used prophylactically for food allergy symptoms. Four randomized trials and two nonrandomized comparisons found that mast cell stabilizers reduced symptoms or severity in children, adults, or both 13-18. Three randomized trials found no benefits 19-21. Side-effects were noted, but were usually not severe.

There was insufficient evidence upon which to base recommendations about other pharmacological treatments. One randomized trial found that H1-antihistamines could have a prophylactic effect 22 and one trial of calf thymus acid lysate derivative found improvement in skin lesions 23. A trial of a herbal treatment was not effective 24.

Dietary interventions

More research was available about dietary interventions. For instance, a number of studies investigated alternatives to cow's milk formula for infants with cow's milk allergy. Here, the evidence base was moderate. Although in common use, cow's milk hydrolyzates were not rigorously compared with standard cow's milk formula alone. Instead, extensively hydrolyzed cow's milk formulas were often used as a comparator in studies of other alternatives such as soy or amino acid-based formulas.

There was some evidence to suggest that extensively hydrolyzed cow's milk formula and amino acid-based formula may be useful long-term management strategies for infants with cow's milk allergy of which extensively hydrolyzed formulas are the first choice. For example, one randomized trial and one nonrandomized comparison found that extensively hydrolyzed cow's milk formulas were well tolerated 25, 26. One systematic review and three randomized trials found that amino acid-based formulas were well tolerated and may reduce symptoms among infants with cow's milk allergy 27-30. The research suggested that amino acid-based formulas may be as effective, or more effective, than extensively hydrolyzed whey formula.

Another systematic review and a randomized controlled trial concluded that soy milk was nutritionally adequate and well tolerated in children allergic to cow's milk (31, 32), but a randomized trial found that soy may be less well tolerated than extensively hydrolyzed whey formula, especially among infants younger than 6 months 33. Two randomized controlled trials suggested that rice hydrolyzate formula was well tolerated among infants with cow's milk allergy and may even reduce the duration of allergy 34, 35. However, another randomized trial found no improvements 36.

There was less evidence about other alternatives to cow's milk. One randomized trial found that almond milk was well tolerated 37. Another randomized trial found that chicken-based formula was better tolerated than soy-based formula 38. A systematic review concluded that donkey or mare's milk was as allergenic as cow's milk 31, but a randomized trial suggested that donkey's milk was better tolerated than goat's milk and reduced symptoms in infants with cow's milk allergy 39.

Our review identified no high-quality studies about other alternatives such as camel's milk or oat milk.

In infants with allergies to food other than cow's milk, a nonrandom comparison found that meat-based formulas were well-tolerated and reduced symptoms 40.

Another key strategy in the long-term management of food allergy involved eliminating the offending food from the diet. Apart from the studies above about eliminating cow's milk for infants, this intervention has received relatively little research attention, perhaps because it is deemed ‘common sense’ that avoidance will reduce symptoms. One randomized trial and one nonrandomized comparison found that eliminating the foods that children were allergic to from the diet was associated with remission of symptoms and reduced reactions to allergens over time 41, 42. This worked well for children allergic to cow's milk or hen's eggs. However, a review and a nonrandomized comparison suggested that dietary elimination may be more difficult for spices 43 or fruit allergies 44. No relevant studies were identified solely focusing on adults.

Dietary supplements

Evidence about the effectiveness of using probiotic supplements as a way to minimize food allergy was mixed. A systematic review, three randomized controlled trials, and one nonrandomized comparison found that probiotic supplements may reduce symptoms and support long-term tolerance in infants with cow's milk allergy or other allergies 45-49. However, five randomized trials found no benefits in infants and one trial found no benefits in young adults 50-55. Some of the studies found that probiotics were more effective in IgE-mediated food allergy.

The review identified no studies meeting the inclusion criteria that focused on prebiotics or other supplements for the long-term management of food allergy.

Allergen-specific immunotherapy

The greatest amount of research focused on different forms of immunotherapy, either with food extracts or cross-reactive pollen extract. Studies generally found that subcutaneous immunotherapy with food extract was associated with improved tolerance and reduced symptoms in children and adults with various food allergies 56, 57. The same was true with cross-reactive pollen extract 58-61 and other extracts. 62 However, the amount of food tolerated remained small and side-effects were common. One randomized trial found no benefit 63.

Another option is sublingual immunotherapy, where allergen extracts are placed under the tongue to promote desensitization. Four randomized trials found that sublingual immunotherapy with food extracts was associated with improved tolerance and reduced symptoms for those with peanut, hazelnut, and peach allergies 64-67. The treatment was generally well tolerated, with few suffering adverse reactions. One randomized trial with cross-reactive pollen extract found no benefit 68.

Two systematic reviews, nine randomized trials, and four nonrandomized comparisons found that oral immunotherapy (or specific oral tolerance induction [SOTI]) was associated with improved tolerance and reduced symptoms for children and adults with various food allergies 69-82. Around half of participants suffered side-effects, although these were not usually severe. One randomized trial found no benefit 83. One systematic review of oral immunotherapy found mixed evidence and suggested that this should not be recommended as routine treatment 84.

Immunotherapy is currently only a research intervention, but may be promising therapeutically. As with all of other interventions considered in this review, however, the evidence base was overall of low quality. Another issue is that most immunotherapy studies did not explore what happens once the relatively short-term treatment-phase ceases. Whereas most studies of dietary interventions and probiotic supplements have focused on children, the majority of research into injection immunotherapy for food allergy has targeted adults. Studies of oral ingestion have included both children and adults.

There were no high-quality studies identified about other long-term management strategies such as educational or behavioral interventions. Nor did any studies about cost-effectiveness meet the inclusion criteria.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

This is one of the most comprehensive systematic reviews about the management of food allergy ever undertaken. There was a substantial body of experimental evidence uncovered. However, much of it comprises small-scale, relatively low-grade studies. Nonetheless, there was some evidence that H1-antihistamines can be effective in improving acute cutaneous manifestations of food allergy.

Regarding longer-term management, avoiding or substituting food was a common approach. There was evidence that cow's milk substitutes can be particularly beneficial for cow's milk allergy. There was no evidence to recommend probiotic supplements to improve outcomes in children or adults with food allergy.

A large quantity of research has been undertaken about different forms of immunotherapy. Although immunotherapy is not currently used in routine practice, the preliminary data were encouraging and further study is warranted. It is important to balance the benefits with the risks of immunotherapy, and further investigation is required to explore any subgroups that may benefit most. It is uncertain whether any gains in tolerance will continue while on treatment or when treatment ceases. Where studies did examine this, tolerance tended to persist only for a few months after immunotherapy ceased.

Strengths and limitations

This review included the most up-to-date research about both the acute and long-term management of food allergy, with studies from Europe, North America, Asia, and Australasia. It was conducted using stringent international standards and drew on a substantially greater evidence base than previous reviews on this subject (85, 86).

However, the studies included were heterogeneous, meaning that meta-analysis was not possible. The inclusion criteria meant that studies about educational, behavioral, and psychological interventions were omitted as these tended to be investigated using uncontrolled before-and-after designs or lower quality methods. Safety was assessed only in some studies. Further trials using standardized measures of side-effects are required to assess the risks associated with different treatments. Furthermore, the review was unable to quantify overall treatment effects, draw conclusions about the comparative effectiveness of different management approaches or the population subgroups that may benefit most.

Conclusions

Food allergy is complex because the best management strategy is likely to depend on exactly what the person is allergic to, the ways this manifests, the types of treatments they have tried in the past and their responses to those treatments.

There is weak evidence to recommend H1-antihistamines to alleviate immediate, non-life-threatening symptoms in children and adults with food allergy. There is also weak evidence to recommend mast cell stabilizer drugs for the prophylactic treatment of symptoms in some children or adults with food allergy.

There is moderate evidence to recommend alternatives to cow's milk formula for infants with cow's milk allergy. Extensively hydrolyzed whey formula and amino acid-based formula have been found to have benefits, with less evidence for soy and rice hydrolyzate. There is no evidence for other foods or for how foods should be re-introduced to the diet.

There is more encouraging evidence to support further exploration of immunotherapy, although the quality of the evidence base is questionable and the treatment is often associated with adverse effects. Further research could usefully explore whether the benefits of treatment continue after the intervention is stopped, as this is an area where there are limited data.

Overall, the review suggests that there is an urgent need to better understand how to support the millions of people who suffer from food allergy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of EAACI and the EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group in developing this systematic review. We would also like to thank the EAACI Executive Committee for their suggestions.

Funding

EAACI.

Author contributions

AS, AM, DdS, and GR conceived this review. The review was undertaken by DdS, MG, and colleagues at The Evidence Centre. DdS led the drafting of the article, and all authors commented on drafts of the article and agreed the final version. This review was undertaken as part of a series managed by SSP and overseen by AS.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.