Venous outflow in partial heterotopic liver transplantation with spleen replacement: Evidence of no chronic venous hypertension

We recently described the first case of partial heterotopic liver transplantation replacing the spleen with delayed recipient hepatectomy to overcome the problem of organ shortage and to make possible debated indications for liver transplantation.1, 2

The surgical technique of the RAVAS procedure was described in different steps: before planning the operation1 and after the first procedure performed, with a case report and video of the technique.2

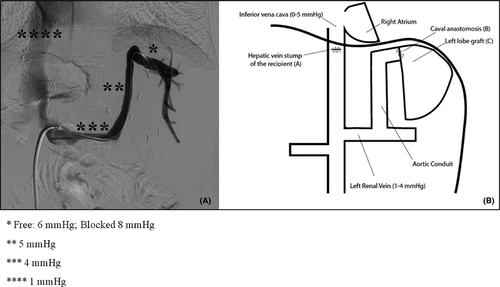

An important criticism comes from Rela et al.,3 who focus on the sub-optimal venous outflow related to the technique. The authors have great experience with heterotopic liver transplantation, and they reported that the pressure in the inferior vena cava increases by 0.77 mmHg for every centimeter below the right atrium. They expected a chronic outflow venous hypertension to occur, and they considered that long-term good outcomes with the RAVAS procedure would not be possible.

We replied to the criticism by showing the optimal Doppler ultrasound examination after one year and the normal liver histology of the graft.4 Furthermore, we involved an expert physiologist (M.C.), who addressed the theoretical hydrostatic pressure within the graft efferent vessel (Figure 1B). Finally, after the proper patient consent, we decided to perform a cavography with the direct measure of the vein pressure at different points, starting from the graft to the atrium.

Our theoretical evaluation was correct: the free pressure in the sovra-hepatic left vein was 6 mmHg and the blocked pressure was 8 mmHg; finally, the pressures were 5 mmHg in the graft conduit, 4 mmHg in the left renal vein, and 1 mmHg in the atrium (Figure 1A).

These gradients are compatible with normal liver function, as presented by the patient after 2 years from the procedure. Moreover, in all imaging examinations performed as a follow-up of the oncological pathology, most of which involved CT with contrast media, no indirect imaging signs of chronic outflow venous hypertension of the liver, such as the diffuse patchy pattern or the clover-like sign, were ever identified.5 Therefore, both laboratory data and imaging examinations confirmed our theoretical evaluation.

Unfortunately, our patient has developed a recurrence of the tumor disease and he has started chemotherapy treatment. Interestingly, the tumor relapse did not involve the transplanted liver.

This preliminary experience needs further refinement, but it seems to have a reasonable theoretical and practical basis to be applied, as reported by other authors.6

The possible expanding indications for liver transplantation with this technique still remain a debated issue, but the opportunity to treat patients without any disadvantage for other liver transplant candidates is a relevant aspect.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.