Donor organ intervention before kidney transplantation: Head-to-head comparison of therapeutic hypothermia, machine perfusion, and donor dopamine pretreatment. What is the evidence?

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Abstract

Therapeutic hypothermia, hypothermic pulsatile machine perfusion (MP), and renal-dose dopamine administered to stable brain-dead donors have shown efficacy to reduce the dialysis requirement after kidney transplantation. In a head-to-head comparison of the three major randomized controlled trials in this field, we estimated the number-needed-to-treat for each method, evaluated costs and inquired into special features regarding long-term outcomes. The MP and hypothermia trials used any dialysis requirement during the first postoperative week, whereas the dopamine trial assessed >1 dialysis session as primary endpoint. Compared to controls, the respective rates declined by 5.7% with MP, 10.9% with hypothermia, and 10.7% with dopamine. Costs to prevent one endpoint in one recipient amount to approximately $17 000 with MP but are negligible with the donor interventions. MP resulted in a borderline significant difference of 4% in 3-year graft survival, but a point of interest is that the preservation method was switched in 25 donors (4.6%) for technical reasons. Graft survival was not improved with dopamine on intention-to-treat but suggested an exposure–response relationship with infusion time. MP was less efficacious and cost-effective to prevent posttransplant dialysis. Whether the benefit on early graft dysfunction achieved with any method will improve long-term graft survival remains to be established.

Abbreviations

-

- ARR

-

- absolute risk reduction

-

- BD

-

- brain death

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- CIT

-

- cold ischemic time

-

- DBD

-

- donation after brain death

-

- DCD

-

- donation after circulatory death

-

- DGF

-

- delayed graft function

-

- ECD

-

- expanded–criteria donor

-

- EP

-

- endpoint

-

- ET

-

- Eurotransplant International Foundation

-

- HR

-

- hazard ratio

-

- ITT

-

- intention-to-treat

-

- ICU

-

- intensive care unit

-

- NNT

-

- number-needed-to-treat

-

- OPO

-

- organ procurement organization

-

- OPTN

-

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

-

- RCT

-

- randomized controlled trial

-

- SCD

-

- standard-criteria donor

1 INTRODUCTION

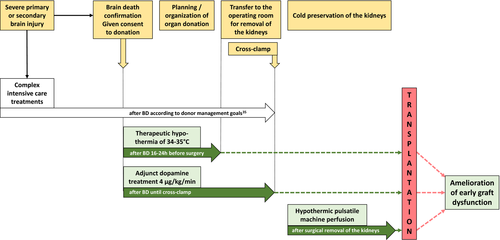

Kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice in end-stage renal disease. However, a substantial gap exists between demand and availability of organs for transplantation. In the United States, approximately 14 000 patients received a kidney transplant from a deceased donor in 2017, but >100 000 patients are currently registered on the transplant waiting list.1 Efforts have been made to optimally use the limited resource of transplantable kidneys by applying sophisticated allocation algorithms, better logistics to shorten ischemic times, and advances in immunosuppressive therapies.2, 3 The quality of donor kidneys can be improved by therapeutic interventions targeting the organ prior to transplantation by means of donor management, medications, and the use of devices for conditioning of organs after removal from a deceased donor.4 In this regard, the European multicenter trial of hypothermic pulsatile machine perfusion (MP) attracted great attention.5 This randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed reduced dialysis requirement after transplantation with machine preserved kidneys as compared to kidneys preserved by simple cold storage. Other strategies, such as donor dopamine pretreatment6 and the induction of mild hypothermia in the brain-dead donor (DBD) before kidney procurement,7 have also been shown to reduce posttransplant dialysis requirement (Figure 1). Reducing delayed graft function (DGF) is an important achievement, because dialysis of patients with nonfunctioning grafts is costly8 and medically burdensome.9, 10 In the current study, we undertook a head-to-head comparison of MP, therapeutic hypothermia, and donor dopamine pretreatment on basis of the three most prominently published RCTs in this field.5-7 The aim of this review article is to carry out a qualitative and, as best as possible, a semiquantitative assessment of the three methods, because they largely differ in availability and technical feasibility with consequences on transplant-related expenses. We inquired into specificities of trial design, enrollment of study participants, and outcome analyses; estimated the effectiveness in relation to cost; and critically reviewed the results on long-term graft survival if available.11, 12

2 METHODS

The design of each trial was revisited with respect to eligibility criteria, subject recruitment and dropouts, randomization procedure, definition of trial endpoints, data analysis, and interpretation of the data. To enable a semiquantitative comparison, we calculated measures such as absolute risk reduction (ARR) and numbers-needed-to-treat (NNT) from raw data reported with the trial outcomes. The ARR was calculated from the difference between the rate of the primary endpoint in recipients of an untreated and treated graft. The NNT constitutes the inverse of the ARR. Because all trials applied multivariable logistic regression analysis with adjustments, we computed unadjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) conditional on the trial intervention to enhance comparability. These statistical calculations were carried out with Stata Statistical Software for MS Windows (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). On the basis of ARR and NNT, we estimated the cost of treatment, in particular for prevention of one primary trial endpoint, namely posttransplant dialysis in one recipient.

3 OBSERVATIONS

3.1 Trial design and enrollment

Each of the three studies was designed as a multicenter RCT. The hypothermia and dopamine trials involved cardiac donors in the intensive care unit (ICU) after brain death (BD) confirmation before organ procurement. The MP trial commenced at a later point, after organ removal, and additionally included kidneys from donors after circulatory death (DCD). Block randomization stratified by procurement organization, expanded–criteria donor status (ECD), and hypothermic treatment prior to BD confirmation was applied in the hypothermia trial, whereas no blocking or stratification was used in the dopamine trial. The MP trial was based on a paired design, meaning that one kidney from each donor was randomly assigned to MP and the other to static cold storage. However, in 25 of 543 donors (4.6%) the preassigned preservation methods were switched due to aberrant vascular anatomy, which is understandable from the viewpoint of technical feasibility of MP but constitutes a violation of the randomization procedure. Sensitivity analyses excluding these kidney pairs or excluding kidneys with aberrant vessels were not reported. The investigators found in post hoc multivariable analysis that aberrant vascular anatomy had no effect on graft outcome. However, the definition of aberrant vascular anatomy used in the multivariable statistical adjustments (>1 renal artery) was different from the reasons that mandated switching of the preservation method (too small aortic patch/too many renal arteries for a reliable connection to the MP device).5

Eligibility required given consent for donation, and hemodynamic stability in the donor intervention trials, with the particular restriction in the dopamine trial that donors were not treated with adrenergic agents other than norepinephrine <0.4 μg/kg/min. Whereas the hypothermia trial demanded a lower age limit at 18 years for enrollment of donors, the dopamine and MP trials accepted kidneys from donors 16 years or older. Regarding the recipients, both of the donor intervention trials restricted the analyses to ages >18 years, whereas the MP trial also evaluated pediatric transplants in an unspecified number of patients.

Due to the paired design, the number of dropouts was large in the MP trial because preassigned donors from whom one kidney was not transplantable or who had provided one or both kidneys plus another organ to one recipient were excluded (Table 1). Consequently, only 336 of 543 randomized kidney pairs were available for primary analysis in the MP trial, which corresponds to 62%. In the hypothermia and dopamine trials, the percentages were 76 and 92, respectively. A higher rate of kidneys in the hypothermia trial were judged as nontransplantable as compared to the dopamine trial (Table 1).

| Therapeutic hypothermia | Machine perfusion | Donor dopamine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Multicenter RCT | Multicenter RCT | Multicenter RCT |

| Setting/trial region | UNOS region 5, United States | The Netherlands, Belgium, and North-Rhine Westphalia, Germany | Bavaria/BW, Germany |

| Recruitment period | March 2012 – October 2013 | November 2005 – August 2007 | March 2004 – August 2007 |

| Randomization |

Block randomization stratified by OPO ECD status Hypothermic treatment prior to BD |

Block randomization according to trial region 25 preservation methods switched due to aberrant vascular anatomy |

Computer-generated randomization No blocking or stratification |

| Allocation of kidneys to recipients |

According to standard OPTN guidelines and local transplant center acceptance criteria |

According to standard ET rules of organ sharing involving 60 European transplant centers | According to standard ET rules of organ sharing involving 60 European transplant centers |

| Intervention | Induced hypothermia (34-35°C) vs normothermia (36.5-37.5°C) prior to procurement | Hypothermic machine perfusion vs static cold storage after organ removal | Dopamine of 4 μg/kg/min until cross-clamp vs no dopamine |

| Mode of action | Unknown | Unknown | Related to antioxidant properties of dopamine |

| Primary endpoint | Need for dialysis during 1st wk |

Need for dialysis during 1st wk |

Need for >1 dialysis during 1st wk |

| Trial subjects | Donors after declaration of BD | Donated kidneys from DBD plus 42 DCDa | Donors after declaration of BD |

| Eligibility of donors |

Given consent to donation Authorization for research Age >18 years Hemodynamic stability according to UNOS Region 5 DMGs35 |

Given consent to donation Age >16 years |

Given consent to donation Current S-creatinine <2.0 mg/dL S-creatinine <1.3 mg/dL on admission No vasopressors other than norepinephrine<0.4 μg/kg/min |

| Eligibility of recipients | Age >18 years |

Only transplanted kidney pairs considered Combined transplants excluded Recipient death during 1st wk excluded |

Age >18 years |

| No. of donors randomized | 370 | 543 | 264 |

| No. of recipients evaluated | 566 | 672 (main data set)a | 487 |

| Reasons for exclusion from primary efficacy analysis after trial assignment |

68 donors excluded 14 had all organs discarded 54 had both kidneys not transplantable 21 donors had one kidney not transplantable 6 kidneys with missing data on DGF excluded |

184 donors excluded 14 donation procedures cancelled 45 had both kidneys not transplantable 25 donors had one kidney not transplantable 80 donors provided a dual or combined organ transplantation 20 donors had other reason 23 additional kidney pairs excluded 14 rejection of one kidney at center 7 technical failures of machine perfusion one death during 1st week one lost to follow-up |

5 donors excluded 5 had both kidneys not transplantable 13 donors had one kidney not transplantable 18 kidneys allocated to recipients <18 years excluded |

| Dual kidney transplants |

11 donors provided a dual transplantation to one recipient |

Excluded from analysis | Not done |

- BD, brain death; BW, Baden-Wuerttemberg; DBD, donation after brain death; DCD, donation after circulatory death; DGF, delayed graft function; DMG, Donor Management Goal; ECD, expanded-criteria donor; ET, Eurotransplant International Foundation; OPO, organ procurement organization; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; RCT, randomized controlled trial; UNOS, United Network of Organ Sharing.

- a Main data set including 588 DBD and 84 DCD kidneys.

The allocation of kidneys to recipients was not study driven but obeyed current national standards of organ sharing in the country where the trial was conducted. Requirement for any dialysis during the first week after transplantation was taken as the primary outcome measure in the hypothermia and MP trials, whereas need for >1 dialysis posttransplant during the first week was defined as primary endpoint in the dopamine trial (Table 1).

Outcomes were evaluated according to the intention-to-treat principle in the hypothermia and dopamine trials, in the sense that any kidney transplanted from a randomized donor was considered in the efficacy analysis. Due to incomplete data on DGF, 6 recipients (1%) were lost in the hypothermia trial. The dopamine trial had no missing data on the primary trial endpoint (Table 1). In the MP trial, analyses were carried out per protocol according to the paired study design.

3.2 Primary trial outcome – reduction of dialysis during the first posttransplant week

All trials reported numbers and percentages of the primary outcome in treatment and control groups, respectively. For statistical comparisons, the hypothermia and dopamine trials used 2-sided Fisher's exact tests, whereas the MP trial applied McNemar's test for evaluation of paired data (Table 2). All trials also used multivariable logistic regression to adjust for possible confounding influences, which uniformly resulted in significantly reduced ORs of the trial interventions. Unadjusted 2-sided ORs were likewise significant in the hypothermia and dopamine trials but were neither reported nor significant after recalculation from the raw data in the MP trial (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.51-1.04; P = .10).

| Therapeutic hypothermia | Machine perfusion | Donor dopamine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conduct of analysis | On intention-to-treat | Per protocol | On intention-to-treat | |||

| Relevant covariates | ||||||

| Donor age, y | 45 vs 45 | P = .82 | 51 | - | 51 vs 51 | P = .89 |

| ECD, n (%) | 40 (26.7) vs 41 (27.0) | P > .99 | 94 (28.0) | - | 37 (30.3) vs 39 (28.5) | P = .79 |

| CIT, h | 13.9 vs 15.6 | P = .02 | 15.0 vs 15.0 | P = .30 | 13.7 vs 14.2 | P = .25 |

| Incidence of primary EP, n (%) | 79/280 (28.2) vs 112/286 (39.2) | P = .008a | 70/336 (20.8) vs 89/336 (26.5) | P = .05b | 56/227 (24.7) vs 92/260 (35.4) | P = .01a |

| Absolute risk reduction, % | 10.9 | 5.7 | 10.7 | |||

| Number-needed-to-treat | 10 donors for prevention of primary EP in two recipients | 18 kidneys for prevention of primary EP in one recipient | 10 donors for prevention of primary EP in two recipients | |||

| Crude OR (95% CI) | 0.61 (0.43-0.87) | P = .006 | 0.73 (0.51-1.04) 0.75 (0.49-1.13) | P = .10 P = .20c | 0.60 (0.40-0.89) | P = .01 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 0.62 (0.43-0.92) | P = .02d | 0.57 (0.36-0.88) 0.61 (0.37-1.00) | P = .01eP = .05c | 0.54 (0.35-0.83) | P = .005f |

| Attributable costs of intervention | None | $948 per kidneyg | $11.55 per donorh | |||

| Costs for prevention of primary EP in one recipient | None | $17 064 | $58 | |||

- ECD, expanded-criteria donor; EP, endpoint; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CIT, cold ischemic time.

- a P value calculated using 2-sided Fisher's exact tests.

- b P value calculated using McNemar's test for paired data.

- c Brain-dead donors only.

- d Adjusted for procurement organization, ECD vs SCD donors, creatinine level at enrollment, donor age, cold ischemic time.7

- e Adjusted for donor and recipient age, ECD vs SCD donors, cold ischemic time, panel reactive antibodies, HLA-mismatches, duration of pretransplant dialysis, repeat transplant, cardiac donor vs heart beating donor.5

- f Adjusted for donor age, donor treatment with norepinephrine, blood pressure, urine output, cold ischemic time, recipient body weight.6

- g Calculated from the difference in costs of machine perfusion and static cold storage.16

- h Underlying the requirement of a 250 mL bag of dopamine intravenous infusion solution (1.6 mg/mL-D5%) per donor.15

The NNT for prevention of the primary trial endpoint was higher in the MP trial (Table 2). In this trial, there were no significant differences in the magnitude of the treatment effect comparing kidneys from ECD vs SCD and DBD vs DCD. It is of interest that a recent post–hoc subgroup analysis of the trial indicated that a significant effect of MP on a reduced incidence of DGF was restricted to kidneys transplanted with cold ischemic times (CIT) <10 hours.13

Owing to overwhelming efficacy, the data and safety monitoring board recommended to terminate the trial of therapeutic hypothermia after approximately half the anticipated donors were enrolled.7 A prespecified subgroup analysis demonstrated enhanced efficacy particularly in ECD kidneys from brain-dead donors (DBD) with an OR of 0.35, 95% CI 0.17-0.69, P = .003.

Post hoc analyses in the dopamine trial suggested that the treatment effect was greater in recipients whose kidneys were transplanted with prolonged CIT (P = .008). In addition, reanalyzing the data in strata of dopamine infusion time suggested positive correlations between treatment duration, dialysis independency, and recovery of kidney function by day 7 (P = .01).6

3.3 Costs of intervention

Induction and maintenance of therapeutic hypothermia in the ICU took 16 to 24 hours after BD declaration.7 The trial intervention did not cause additional cost, because the median time interval in the United States from BD declaration to cross clamp is 23.8 hours (interquartile range 17.8-31.0 hours).14 The extra cost from adjunct donor dopamine treatment is equivalent to the commercial price of one bag of dopamine intravenous infusion solution.15 Treatment costs of hypothermic MP are derived from the cost for use of the LifePort Kidney Transporter machine relative to the cost of static cold preservation. According to an economic evaluation of cost-effectiveness, the MP trial investigators have calculated the unit costs for MP at $1182 and for static cold storage at $234, thus resulting in a difference of $948 per kidney.16 Hence, the estimate of the NNT cost for preventing one primary trial endpoint in one recipient approximated $17 000 with MP but was zero or negligible with the donor interventions before procurement (Table 2).

3.4 Graft survival

Data on graft survival are not yet available from the hypothermia trial but are expected to be published in 2019 (personal communication with the authors). The MP trial provided survival data after 3 years and the dopamine trial after 5 years released in a separate publication after the report of the primary trial results.11, 12 The MP trial depicted several graft survival curves, including post hoc subgroup analyses, which indicated a small advantage in favor of the trial intervention. P values are based on adjusted hazard ratios (HR). A 2-sided log rank test, which would be of interest in this MP trial because the distribution of confounders was virtually identical in the treatment and control groups, was not provided. Death-censored graft survival was 91% vs 87% at 3 years, with an adjusted HR of 0.60, 95% CI 0.37-0.97, P = .04, when the entire study population was considered, including 588 kidneys from a brain-dead donor (DBD) and 84 kidneys from donors after circulatory death (DCD). The benefit appeared to be particularly enhanced in the subgroup of 188 recipients who had received an ECD kidney from a DBD, showing graft survival rates of 86% vs 76%, adjusted HR 0.38, 95% CI 0.18-0.80, P = .01. Another conclusion from this observation is that the effect of MP on graft survival is marginal in kidneys from SCD. Given an overall survival of 91% vs 86% in favor of MP for 588 DBD kidneys analyzed, and a 10% difference for the subgroup of 188 ECD kidneys, the remainder of the survival advantage approximates at only about 2% in SCD kidneys.

The dopamine trial failed to demonstrate a graft survival advantage on intention-to-treat (83% vs 80%, log rank P = .42). An association between duration of the dopamine infusion and 5-year graft survival was noted, which was borderline significant in univariate analysis (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.92-1.00 per hour, P = .05), but reached significance in multivariable analysis after adjustment for potential confounding influences (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.90-0.99 per hour, P = 0.03). In a secondary post hoc analysis, a threshold of 7 hours of donor dopamine treatment could be identified above which a survival advantage was evident (90% vs 80%, log rank P = .04).12

3.5 Safety aspects

Induction of therapeutic hypothermia appears to be safe in the DBD. None of the side effects (one episode of dysrhythmia and hypertension each) associated with this trial intervention rendered the donor unsuitable for donation. To date, safety assessments are restricted to hemodynamic and respiratory stability of the DBD and the number of organs transplanted from these donors.7 Outcomes of nonrenal organs after transplantation are pending.

In the dopamine trial, circulatory side effects (hypertension >160/90 mm Hg and/or tachycardia >120 beats/min) occurred in 15 of 120 DBD (12.5%) after administration of the trial drug, but were fully reversible within a few minutes in all instances after premature termination of the dopamine infusion. Consequently, not a single donor was prevented from organ donation and all kidneys transplanted from these donors were evaluated according to trial group assignment on intention-to-treat.6 Furthermore, the outcomes of kidneys from donors who were withdrawn from dopamine treatment for side effects (n = 15) or remained untreated despite assignment to dopamine (n = 6) were compared with kidneys from untreated controls and exhibited similar results.12 Different from the hypothermia trial, the dopamine trial has already evaluated posttransplant performance of livers and hearts from multiorgan donors. Donor dopamine of 4 μg/kg/min did not confer harmful effects on short- and midterm outcomes after liver transplantation17 and was associated with improved outcome of cardiac allografts.18 Three-year cardiac graft survival was 87.0% with hearts from dopamine–treated donors vs 67.8% with controls, log rank P = .03 (Table 3).

| Therapeutic hypothermia | Machine perfusion | Donor dopamine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention related adverse events, n (%) |

One episode of dysrhythmia and hypertension each n = 2 (1.1) |

Technical failure of machine perfusion n = 7 (2.1) |

Hypertension >160/90 mmHg and/or tachycardia >120 beats/min n = 15 (12.5) |

||

| Action taken | Not reported | Organ automatically preserved by means of cold storage inside the machine | Fully reversible after reduction/termination of the dopamine infusion | ||

| Included in analysis of efficacy | Included in ITT analysis | Excluded from analysis | Included in ITT analysis | ||

| No. of nonrenal organs transplanted | |||||

| Livers, n (%) | 129 (71.7) vs 135 (71.1)a | P = .91 | - | 99 (79.8) vs 106 (75.7)b | P = .46 |

| Hearts, n (%)c | 46 (25.6) vs 49 (25.8)a | P > .99 | - | 49 (39.5) vs 50 (35.7)b | P = .53 |

| Pancreases, n (%) | 19 (10.6) vs 15 (7.9)a | P = .47 | - | 23 (18.5) vs 24 (17.1)b | P = .87 |

| Liver allograft survival, % | Pending | - | 59.6 vs 62.0d | P = .71 | |

| Heart allograft survival, % | Pending | - | 87.0 vs 67.8e | P = .03 | |

- ITT, intention-to-treat.

- a Referred to 180 and 190 donors of the hypothermia and control group who underwent initial randomization for trial enrollment.

- b Referred to 124 and 140 donors of the dopamine and control group who underwent initial randomization for trial enrollment.

- c Organ donors anticipated to donate thoracic organs were not enrolled during initial phase of the trial.

- d Including 15 split liver transplants and 22 acute retransplants until 3 years after transplantation.17

- e Primary heart transplants until 3 years after transplantation.18

The MP trial reported on 7 kidneys (2%) with technical failure of MP. The investigators mentioned in a footnote to a summary table of adverse events that none of these technical perfusion failures rendered the kidney unsuitable for transplantation, because the kidney was automatically preserved by means of cold storage inside the machine. However, these kidneys were excluded from the efficacy analyses and their performance after transplantation was not reported.5 In this context, it should be pointed out that even if only two instances of DGF were attributable to a complication of MP, the findings on the level of statistical significance in the MP trial would be obscured given the moderate effect.

4 DISCUSSION

All three trials examined in this study showed a significantly reduced dialysis requirement during the first week posttransplant. The MP trial was based on a strictly paired design, which led to a large dropout rate of almost 40% after randomization. This large dropout rate limits to some extent the ability of this trial to inform about the prospective use of MP, because it is difficult to discern what part of the initial trial population is represented in the outcome data. Nevertheless, in support of the MP method, several meta-analyses showed that MP reduces DGF of kidneys from all donor types, including DBD, DCD, and ECD.19-22

The difference in the definition of the primary endpoint constitutes a limitation in the comparison of the study results. At variance with the MP and hypothermia trials, the dopamine trial focused on the requirement of >1 posttransplant dialysis session during the first week to address possible confounding by indication. To date, there is no agreement among nephrologists on specific criteria for initiation of dialysis after transplantation. A single dialysis session only, particularly in the immediate postoperative period, may foremost be necessary because of the recipient's medical condition, ie, for the correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalance, rather than reflecting graft dysfunction. Accordingly, the dopamine trial defined in our opinion a more appropriate surrogate of graft dysfunction by eliminating a few recipient-related dialysis indications. In support of this notion, the need for more than one dialysis session was found to profoundly reduce the ultimate prognosis of the kidney graft (P < .001), whereas a single dialysis did not (P = .93).12 It is very unlikely that the effect of dopamine pretreatment was arbitrarily overestimated by the use of a more specific surrogate endpoint of early graft dysfunction. It is furthermore of interest that, even if the three methods were equally protective for the kidney, unlike with MP that by definition affects one kidney, intervening in the donor before organ procurement will subsequently affect the transplant outcomes in two recipients.

Another limitation may come from the higher dialysis rate in controls in the hypothermia and dopamine trials (Table 2). A higher overall dialysis rate also influences the amplitude of the ARR, which was one of the metrics used to compare the efficacy of the three interventions in the present analysis. The MP trial investigators suspected that the relative large number of exclusions, in particular the exclusion of donors of whom one kidney was discarded due to the paired trial design, may have incurred a bias toward a selection of better donors,5 whose kidneys were less likely to experience DGF after transplantation. However, the beneficial effect on DGF was even stronger in the MP trial as compared to the effects obtained from meta-analyses of former smaller trials and of retrospective studies.23 The kidneys investigated in these studies had also markedly longer CITs predisposing them to an increased risk of DGF after transplantation. Interestingly, and supporting a notion that CIT length may influence the efficacy of MP, the MP trial investigators found in a recent post hoc analysis that the effect on DGF was largest for kidneys exposed to CIT <10 hours.13 These findings make it appear unlikely that the lessened ARR in the MP trial was merely caused by the lower baseline dialysis rate. One also needs to bear in mind that any donor organ treatment administered before organ procurement will affect the outcome of two kidneys. This will enhance the quantitative effect irrespective of the estimated ARR and reduce the NNT by half. Not surprisingly therefore, compared to MP, therapeutic hypothermia and dopamine provided superior cost-effectiveness. The hypothermia trial was conducted in the United States, where the duration of trial intervention of 16–24 hours did not affect ICU stay. However, it should be noted that there is variation between practice in the United States and Europe, with reported longer periods of donor management in the former.14, 24 This should be taken into account from the viewpoint of cost when extrapolating the data of the hypothermia trial to a European setting. Nevertheless, additional expenses arising from a lengthened ICU stay are limited and likely negated by savings of posttransplant dialysis costs. It also remains to be seen whether shorter time periods of hypothermia are equally protective.

Dopamine is inexpensive and easy to use and no organizational effort is necessary for prolonged stay in the ICU or the use of additional facilities, such as the LifePort Kidney Transporter. During recent years, due to its ineffectiveness for prevention or amelioration of renal failure in the critically ill, renal-dose dopamine has decreased in importance as a first-choice drug in intensive care medicine. Dopamine's reintroduction as a routine adjunct treatment in the stable DBD, administered during the time from brain death declaration to cross-clamp, would offer an easy and safe procedure for improvement of immediate graft function. In addition, preliminary observational data suggest that low-dose dopamine may provide an additive effect to the benefit of a lower core body temperature in the DBD.25 This may open the perspective of combining therapeutic hypothermia with dopamine pretreatment in the deceased kidney donor.

With respect to graft survival, a small advantage in favor of MP preserved kidneys was noted in the MP trial. Overall, graft survival of MP preserved kidneys was 4% better at 3 years than that of cold stored control kidneys, a result that reached marginal significance after multivariate statistical modeling. The improvement was pronounced in the subgroup of ECD kidneys,11, 26, 27 suggesting that normal risk kidneys scarcely survived better. Whether MP preservation indeed would confer a survival benefit for the latter (the largest) subgroup of kidneys is therefore doubtful. Several meta-analyses involving either RCTs or observational nonrandomized studies19-21 as well as registry analyses28 failed to demonstrate that MP – despite a consistent beneficial effect on DGF – confers an overall graft survival advantage. It should also be noted that previous reports on the relevance of DGF for graft survival varied considerably, because the definition of DGF was poorly standardized.28, 29 Because graft survival is influenced by a great number of additional, mainly recipient–related factors, multifactorial analysis of large transplant series considering multiple confounders will be required for obtaining a conclusive answer whether graft survival is superior depending on the preservation method. With a statistical power of 0.8 and a 2-sided type I error of 0.05, the required sample size approximates 1000 kidney pairs at minimum for reliable detection of a 4% improved graft survival.

Although donor dopamine treatment did not translate into a significant graft survival advantage on intention-to-treat analysis, a significant association of the dopamine infusion time with graft survival was found in multivariable Cox regression analysis after 5-year posttransplant follow-up.12 The significance of this finding awaits confirmation. The molecular mechanisms conferring kidney protection by dopamine are not related to circulatory effects but rather depend on dopamine's antioxidant properties.30-33 Dopamine's effectiveness requires diffusion into cells,34 which under the steady–state conditions of continuous infusion is a time-dependent process. That the dopamine infusion time may be a critical entity is therefore conceivable. In retrospect, it was a protocol shortcoming that the dopamine trial did not specify a minimum infusion time, with the result that a number of the donors may have been treated for an insufficiently short time period.12

5 CONCLUSIONS

All three methods examined in this study had shown efficacy in previously published RCTs for the reduction of dialysis requirement after kidney transplantation. Based on our analysis, we conclude that, compared to therapeutic hypothermia and dopamine pretreatment, MP provides the smallest treatment effect and incurs by far higher cost for achieving a reduced rate of DGF. Whether the beneficial effect of any of the three methods on early graft dysfunction will translate into improved graft survival has not yet been conclusively clarified.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.