Ipilimumab for the treatment of advanced melanoma in six kidney transplant patients

Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are new therapeutic options for metastatic melanoma, but few data are available in organ transplant recipient populations. Six French patients, three men and three women, mean age 66 years (range 44-74), all kidney transplant recipients, received ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor) for metastatic melanoma. At diagnosis of advanced melanoma, immunosuppressive therapy had been minimized in all but one. Adverse effects included one case of grade 1 diarrhea and one of grade 1 pruritus. One patient had acute T cell–mediated rejection confirmed by histology after the first injection of ipilimumab. After a median follow-up of 4.5 (3-20) months, one patient achieved partial response, one had stable disease, and four had disease progression. All the patients died, five from melanoma, one from another cause. In this series and in the literature, ipilimumab proved to be safe and possibly active. The acute rejection we encountered was probably related to both a rapid, drastic reduction of immunosuppression and the use of ipilimumab. Our safety data on ipilimumab contrast with the organ transplant rejections already reported with PD-1 inhibitors. We consider that immunosuppression should not be minimized, as the impact on metastatic disease control is probably small.

Abbreviations

-

- ADPKD

-

- autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

-

- BRAF

-

- B- rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma

-

- CTLA-4

-

- cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

-

- EVR

-

- everolimus

-

- ICI

-

- immune checkpoint inhibitors

-

- IS

-

- immunosuppression

-

- MM

-

- metastatic melanoma

-

- MMF

-

- mycophenolate mofetil

-

- mTOR

-

- mammalian target of rapamycin

-

- OTR

-

- organ transplant recipients

-

- P

-

- prednisone

-

- PD-1

-

- programmed death 1

-

- Po

-

- prednisolone

-

- TAC

-

- tacrolimus

1 INTRODUCTION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), such as anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), ipilimumab, or antiprogram death 1 (PD-1), are widely used in advanced tumors. In the setting of metastatic melanoma (MM), previous studies have shown prolonged responses and improved survival rates, and these treatments have become the standard of care.1-3

Organ transplant recipients (OTR) have an increased risk for various types of cancer, including melanoma, but are not included in clinical trials. Data on the use of ICI in this population are sparse. Cases have been recently published reporting the efficacy and safety of ipilimumab for MM in kidney,4 liver,5, 6 or heart7 recipients, whereas anti-PD-1 ab therapy is widely reported to cause transplant rejection.8-14

We present here a French nationwide retrospective study on OTR patients treated with ICI for MM.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

This multicenter retrospective study included OTR patients treated with ICI: ipilimumab or anti-PD-1 (nivolumab or pembrolizumab) for MM in France from July 2012 to June 2015. Cases were identified by the members of the French Oncodermatology Group (Groupe de Cancérologie Cutanée), which includes general and university hospitals. We collected demographic data, history of the kidney transplantation, history of the melanoma, and outcomes under ICI. Institutional review board approval was obtained from CPP Ile de France XI for this study performed on the Melbase cohort. Clinical follow-up was completed by September 2017.

3 CASE DESCRIPTIONS

We report the cases of six kidney transplant recipients treated with ipilimumab for MM in five centers (Table 1). The mean time from renal transplantation (RT) to the initiation of ICI was 5 years (range 0.8-23). Five patients were first-time kidney recipients; one had had two previous RTs. Two patients had a medical history of cancer before RT, including localized cutaneous melanomas.

| Patient | Gender, age | Past medical history before RT | Etiology of underlying renal failure | Time from RT to primary melanoma diagnosis (months) | Time from primary melanoma to metastatic disease (months) | Time from RT to initiation of ipi | AJCC stage at the initiation of ipi | Baseline creatinine serum level (μM) (normal <106) | Baseline eGFR (MDRD, ml/min/1.73 m2)(normal >60) | Baseline LDH serum level (normal <250) | Number of ipi injections | Nephrologic changes | Melanoma outcome | Overall outcome | Advanced melanoma treatment after ipi | Follow up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M, 67 | 0 | Diabetic nephropathy and nephroangiosclerosis | 23 | 4 | 27 | IIIc | 180 | 35 | 1.5ULN | 4 | Increased proteinuria | PD | Death due to melanoma | 0 | 4 |

| 2 | F, 57 | 0 | ADPKD | 37 | 0 | 67 | IV M1ca | 85 | 64 | N | 4 | No | PD | Death due to melanoma | 0 | 5 |

| 3 | M, 74 | Prostate carcinoma, renal papillary carcinoma | IgA nephropathy | 7 | 48 | 57 | IV M1c | 90 | 76 | N | 3 | No | PD | Death due to melanoma | nivolumab 1 injection | 4 |

| 4 | F, 68 | 2 primary cutaneous melanomas | ADPKD | 21 and 29 before | 37 | 10 | IV M1c | 76 | 70 | N | 4 | No | PD | Death due to melanoma | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | F, 44 | 0 | Reflux nephropathya | 294a | 15 | 311 | IV M1c | 120 | 45 | N | 1 | Acute cellular rejection | SD | Death due to infection and melanoma | dacarbazine 1 injection | 15 |

| 6 | M, 66 | 0 | IgA nephropathy | 271 | 6 | 281 | IIIc | 139 | 47 | N | 4 | No | PR | Death due to cardiac disorder | 0 | 26 |

- ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer 2009; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; F, female; ipi, ipilimumab; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; M, male; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; N, normal range; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RT, renal transplantation; SD, stable disease; ULN, upper limit of normal range.

- Dacarbazine as 1st line therapy.

- 2 previous RTs, complicated with chronic and superacute rejection.

- After first RT.

Primary melanomas were diagnosed on average 37 (range 7-271) months after RT in five other patients.

Metastatic disease was diagnosed within a median of 11 (range 0-48) months after the primary melanoma. No patient had brain metastasis or BRAF-mutant melanoma; all but one were treatment naïve.

Screening for donor-specific antibodies (DSA) at initiation of ICI was positive for one patient out of five tested.

The management of advanced melanoma also involved a change in immunosuppressive regimen in all patients but one, who was already under minimal therapy on account of his past history of cancers (Table 2). The median time between the last immunosuppression (IS) modification and initiation of ICI was 5 months (range 0-38).

| Patient | IS at time of advanced melanoma diagnosis | IS modifications at time of advanced melanoma diagnosis | IS at time of ipi initiation | Time between last change in IS and first ipi injection (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TAC MMF Po | Switch TAC > EVR, MMF Po continued | MMF EVR Po10 | 0 |

| 2 | TAC MMF | ↓MMF, ↓TAC | SRL P | 8 |

| 3 | AZA EVR P5 | None | AZA EVR P5 | 38 |

| 4 | TAC EVR P5 | ↕TAC, ↑P20, ↑EVR, add MMF | MMF EVR P20 | 1 |

| 5 | EVR P | ↕EVR, P continued | P20 | 1 |

| 6 | CSA P5 | Switch CSA > EVR, P continued | EVR P5 | 8 |

- AZA, azathioprine; CSA, cyclosporin; EVR, everolimus; IS, immunosuppressive treatment; ipi, ipilimumab; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; N, normal range; NA, not available; P, prednisone (mg/day); Po, prednisolone (mg/day); PD, progressive disease; RT, renal transplantation; SD, stable disease; SRL, sirolimus; TAC, tacrolimus; ULN, upper limit of normal range. ↓, dose reduction; ↕, discontinuation; ↑, dose increase.

Ipilimumab (3 mg per kilogram every 3 weeks for 4 scheduled injections) was administered to all patients, as it was the approved first-line therapy at that time, anti-PD-1 being restricted to ipilimumab failure. Their outcomes are detailed hereafter. All six patients ultimately died, median 4.5 (range 3-26) months after ICI initiation, five from melanoma, one from another cause.

3.1 Patient 1

A 67-year-old man had RT for nephroangiosclerosis and diabetic nephropathy in December 2012. He was diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma in October 2014, while on tacrolimus (TAC), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and prednisolone 10 mg/day (Po10). Despite wide excision, he rapidly presented with unresectable cutaneous and lymph node metastases, BRAF wild type, NRAS mutant. TAC was replaced by everolimus (EVR) just before the first ipilimumab injection in March 2015. Tolerance was good, with grade 1 pruritus and stable creatinine serum levels. Proteinuria increased from 0.7 g/l to 1.5 g/l after the fourth injection, attributed to the switch to EVR. He developed pleural effusion, bone, small intestine, and brain metastases and died from melanoma in July 2015.

3.2 Patient 2

A 57-year-old woman was diagnosed with lentigo malignant melanoma in January 2010. She first noticed this lesion in 2008, 1 year after RT for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). At the time of the melanoma diagnosis, she was receiving MMF and TAC, and she had lymph node metastases. Management of this tumor involved wide cutaneous excision, superficial parotidectomy, cervical node dissection, and reduction of the dosage of MMF and TAC. Three months later, liver BRAF wild type metastases were found. She was treated with three cycles of dacarbazine, resulting in an ongoing disease progression. In November 2011, MMF and TAC were replaced by sirolimus (SRL) and prednisone (P). Screening for DSA was negative before starting ipilimumab in July 2012. Tolerance was good, with stable creatinine serum levels, and grade 1 diarrhea. She unfortunately developed brain and bone metastases and died from melanoma in December 2012.

3.3 Patient 3

A 74-year-old man had RT in May 2010 for IgA nephropathy diagnosed in 1992. He was on peritoneal dialysis since June 2009. Prior to RT, he had class I anti-HLA antibodies. During the perioperative period, he received TAC, MMF, and P15. He was diagnosed with prostate carcinoma in 2004 and localized kidney papillary carcinoma in 2009, both treated surgically. Given his past history of cancer, TAC was replaced by EVR 6 months after RT; at this time, in November 2010, he developed a melanoma on the trunk treated by wide-margin excision. In November 2011, MMF was replaced by azathioprine (AZA) because of BK viremia. In July 2014, he received intravenous immunoglobulins after detection of DSA. In November 2014, metastatic progression of the melanoma was diagnosed, localized in the nodes, lung, and liver, BRAF wild type, NRAS mutant. First-line treatment with ipilimumab started in December 2014. Screening for DSA remained positive. After the second injection, EVR dosage was increased and AZA reduced. Ipilimumab was stopped after three injections because of rapid clinical progression. PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab, available as second line in an expanded-access program, was introduced in March 2015, at the usual dose of 3 mg per kilogram every 2 weeks, combined with stereotaxic radiotherapy on hilar compressive adenopathy. He rapidly presented with fever, dyspnea, grade 1 diarrhea, and renal dysfunction; Escherichia coli sepsis on the renal graft was diagnosed. After an initial improvement, respiratory distress relapsed; bronchoalveolar lavage showed hyperlymphocytosis, slight hypereosinophilia (3.5%), and no pathogen. His condition continued to deteriorate and he ultimately died from melanoma in April 2016.

3.4 Patient 4

A 68-year-old woman had RT for ADPKD in August 2014. She had a past history of two primary skin melanomas on the left thigh, in March and November 2012, 21 and 29 months before RT. RT was not contraindicated at the time because they were thin melanomas (Breslow 0.5 and 0.6 mm, AJCC 2009 T1N0M0), with a low risk of recurrence. Prior to RT, screening for DSA and anti-HLA antibodies was negative. During the perioperative period, she received basiliximab, TAC, MMF, corticosteroids, and a switch to EVR was scheduled at 3 months posttransplant. Her posttransplantation history showed a villous colon adenoma with high-grade dysplasia 3 months after transplantation in December 2014. At that time, she also had a left inguinal lymph node, which led to the diagnosis of BRAF NRAS wild type MM in April 2015, with liver, lymph nodes, lung, and bone metastases. TAC was replaced by MMF and the dosage of EVR and P was increased 1 month before the initiation of ipilimumab in June 2015. After the second injection, she had clinical progression with the occurrence of a symptomatic pleural effusion. She died on September 2015 from respiratory distress and melanoma progression.

3.5 Patient 5

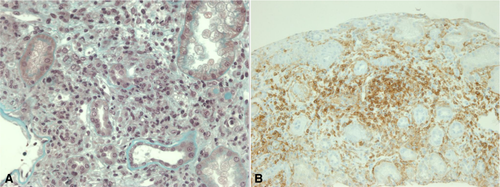

A 44-year-old woman had a third RT in June 2002 for reflux nephropathy. She had had two previous RTs, complicated with chronic and superacute rejection respectively, leading to the removal of both failed transplanted kidneys. In November 2013, she was diagnosed with dorsal desmoplastic melanoma, with in-transit nodules and positive sentinel node biopsy. Surgery was followed by radiation therapy on the primary tumor site, and IS was changed: TAC and MMF were replaced by EVR and P. In October 2014, a DSA DP02 was detected at low titer. In February 2015, a single liver metastasis was found. In March 2015, EVR was stopped and IS was reduced to P20; ipilimumab was started in April 2015. Twenty-seven days after the first injection, she presented with fever and elevated creatinine serum levels from 120 to 430 µmol/L. Transplant renal biopsy showed acute T cell rejection, grade IA, 2005 Banff classification (Figure 1): edema and interstitial infiltration by T-lymphocytes associated with mild glomerulitis lesions. Immunofluorescence showed no C4d deposits. Screening for DSA was negative. She received corticosteroid pulse treatment and TAC and MMF were reintroduced, with an improvement in creatinine serum levels. The last DSA screening, a year later, showed the appearance of a DSA Cw07 (MFI 1000) without any consequence on renal function. Melanoma evaluation at 4 months showed stable disease; she then received a second-line therapy with dacarbazine but died in July 2016 from infectious complications and melanoma progression.

3.6 Patient 6

A 66-year-old man with IgA nephropathy had a RT in 1992. In April 2014, locally advanced melanoma with lymph node involvement was found on his left arm, treated by resection of the primary lesion, and synchronous cutaneous local metastases treated by elective node dissection. He was receiving P5 and cyclosporine; the latter was stopped and replaced by EVR in June 2014. In October 2014, unresectable cutaneous locoregional recurrence was found, BRAF wild type, NRAS mutant. In February 2015, he received a first dose of ipilimumab. Tolerance was excellent, creatinine serum levels remained stable, and screening for DSA was negative at baseline and monthly under treatment. He had a partial response, and a remaining nodule was removed in October 2016. Complete response after surgery was maintained until his death on March 2017, from a cardiac disorder unrelated to melanoma. No postmortem evaluation was performed to rule out the hypothesis of an immune cardiac adverse event, but the cardiologist’s expertise did not support this, even if delayed immune adverse events for ipilimumab, including cardiotoxicity were reported.15

4 DISCUSSION

ICI, first using anti-CTLA-4 then anti-PD-1 and currently combining both, has considerably improved the prognosis of MM. However, the efficacy and safety of treatments increasing T cell activation in patients with therapeutic IS are questionable.

Our first observation is that ICI can show clinical benefit in the OTR population. In this real-life series of six kidney transplant recipients, we observed one stable disease and one partial response opening the possibility for resection and secondary complete response. Although the response rate cannot be accurately evaluated because of the small number of patients, efficacy seems comparable to that usually observed in immunocompetent patients.1 This suggests that therapeutic IS is not systematically deleterious to efficacy, in line with reported data.16 In contrast, a study among patients with autoimmune disease showed a lower response rate to anti-PD-1 for patients on immunosuppressants (15%) than for those not on immunosuppressants (44%).17 In our study, prognosis was poor, with two patients alive at 1 year, one at 2 years, and none at 3 years, as a result of underlying fragility and comorbidities.

Second, the impact of the reduction of IS on disease control cannot be excluded but is doubtful17 and difficult to evaluate in our small series. All but one patient had minimization of their IS. Four patients had disease progression and died, including the patient who did not have any change in IS; the last patient, who responded, had a switch to an mTOR inhibitor at initiation of ICI. The patient who experienced kidney graft rejection received high-dose IS, without any flare in melanoma evolution. To sum up, we consider progression of the melanoma in our patients as evidence of the absence of efficacy of the ICI rather than the inadequacy of IS management. Reducing the IS probably had a little impact on the long-term outcome of a cancer that occurred some time after the transplant. Thus, IS may not need to be reduced prior to ICI, in order to minimize the risk of kidney transplant rejection, and because it has a little impact on advanced oncologic disease control.

Based upon the number of patients that was compiled from the literature review, the organ rejection rate with ipilimumab as monotherapy in OTRs is smaller but not insignificant (23%, 3/13 patients)4, 5, 18-20 (Table 3). Only one of our patients had an acute graft rejection after the first ipilimumab injection in the context of rapid and drastic reduction of IS. Thus the specific roles of each factor (reduction of IS versus immune boost from ipilimumab) cannot be fully determined.

| Reference | Type of ICI | Transplanted organ | Number of patients | Organ rejection? | Type of change in IS regimen | Response or disease control? | Type of tumor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipson et al4 | ipi | Kidney | 1 | 0 | ↓: ↕TAC, P5 continued | 1 | Cutaneous melanoma |

| Ipi | Kidney | 1 | 0 | ↓: ↕TAC, ↕MMF, P5 continued | 1 | Cutaneous melanoma | |

| Qin &Salama19 | ipi | Heart | 1 | 0 | ? | 0 | Melanoma |

| Morales et al5 | ipi | Liver | 1 | 0 | ↓: ↕MMF, ↓SRL | 1 | Cutaneous melanoma |

| Ranganath & Panella20 | ipi | Liver | 1 | 0 | ? | 0 | Cutaneous melanoma |

| Boils et al8 | nivo | Kidney | 1 | 1 | ↓: ↕CSA, P continued | ? | NSCLC |

| Alhamad et al9 | ipi then pembro | Kidney | 1 | 1 | ↓: ↕CSA, P continued | ? | Cutaneous melanoma |

| Spain et al10 | ipi then nivo | Kidney | 1 | 1 | ↓: ↕TAC, Po5 continued | 1 | Cutaneous melanoma |

| Lipson et al11 | pembro | Kidney | 1 | 1 | No: P5 (6 months before, ↕CSA) | 1 | Cutaneous SCC |

| Herz23 | ipi then nivo | Kidney | 1 | 0 | No: TAC, P5 | 0 | Cutaneous melanoma |

| Ong et al12 | nivo | Kidney | 1 | 1 | ↓: ↕TAC, ↕MMF, P10 continued | 1 | Cutaneous melanoma |

| Jose A24 | ipi | Kidney | 1 | 1 | ↓: ↕TAC, Po 5 started | 0 | Ocular melanoma |

| Barnett25 | nivo | Kidney | 1 | 0 | Add Po 40, switch TAC > SRL | 1 | Duodenum |

| Owonikoko et al13 | nivo | Heart | 1 | 1 | ↑: add SRL, TAC and P continued | ? | Cutaneous SCC |

| Kwatra et al14 | pembro | Kidney | 1 | 1 | ↕TAC, ↕MMF, AZA EVR started | 0 | Cutaneous melanoma |

| Kittai et al7 | nivo | Kidney | 1 | 0 | ↕TAC, ↕MMF, P5 continued, SRL started | 1 | Cutaneous SCC |

| nivo | Heart | 1 | 0 | ? cyclosporine, MMF | 1 | NSCLC | |

| Winkler26 | nivo | Kidney | 1 | 0 | ↓: ↕CSA, Po MMF continued | 0 | Cutaneous melanoma |

| Pembro | Kidney | 1 | 0 | No: CSA continued | 0 | Uveal melanoma | |

| Varkaris27 | pembro | Liver | 1 | 0 | ↓: ↓TAC | 0 | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Dueland et al21 | ipi | Liver | 1 | 1 | ↓: ↕SRL ↕MMF, Po10 | 0 | Ocular melanoma |

| Kuo et al6 | ipi then pembro | Liver | 1 | 0 | No: MMF and SRL continued | 1 | Melanoma |

| current series | ipi | Kidney | 1 | 0 | ↕TAC, MMF and P continued, EVR started | 0 | Cutaneous melanoma |

| ipi | Kidney | 1 | 0 | No: ↕TAC, ↕MMF, SRL P started 8 months before | 0 | Cutaneous melanoma | |

| ipi then nivo | Kidney | 1 | 0 | No: AZA EVR P5 | 0 | Cutaneous melanoma | |

| ipi | Kidney | 1 | 0 | ↕ TAC, ↑P20, ↑EVR, MMF started | 0 | Cutaneous melanoma | |

| ipi | Kidney | 1 | 1 | ↓:↕EVR, P continued | 1 | Cutaneous melanoma | |

| ipi | Kidney | 1 | 0 | No: ↕CSA, P5 continued, EVR started 8 months before | 1 | Cutaneous melanoma |

- CSA, cyclosporine; EVR, everolimus; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; ipi, ipilimumab; IS, immunosuppression; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; nivo, nivolumab; NSCLC, non small-cell lung cancer; P, prednisone (mg/day); pembro, pembrolizumab; Po, prednisolone (mg/day); SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SRL, sirolimus; TAC, tacrolimus↓, dose reduction; ↕, discontinuation; ↑, dose increase.

Our safety data obtained for ipilimumab contrasts with the poor tolerance described in the literature toward PD-1 inhibitors among OTRs: transplant rejection was reported in 5 out of 11 patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors alone.8-13, 21 However, ipilimumab is not the best treatment because of a modest response rate, around 15%, and a high toxicity profile; current ICI strategies rely on first-line anti-PD-1, alone or in combination with ipilimumab. No data are available in OTR patients receiving this combination, and physicians and patients should be aware of the risk of organ rejection, which should be closely monitored.

To conclude, ICI have revolutionized the management of MM. They can be used in OTR patients with some efficacy. Ipilimumab could be safer than anti-PD-1 for the risk of organ rejection, but tolerance toward the transplanted organ needs to be documented for combination of ICI. IS alterations should be carefully discussed and probably avoided. Indeed the priority in these life-threatening conditions should focus on defining the most effective anticancer therapy. This needs to be confirmed by further cases, using the European register of organ transplant patients receiving immunotherapy for skin cancer led by the European Academy of Dermato Oncology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Angela Swaine Verdier for language editing.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have potential conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation. CL: employment and research funds from MSD, BMS (board, investigator). LM: employment and research funds from BMS (board, investigator). HM: research funds from BMS and LeoPharma (investigator), employment by Merck, BMS, ROCHE, Pfizer (board). The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.