Survival of Recipients of Livers From Donation After Circulatory Death Who Are Relisted and Undergo Retransplant for Graft Failure

Abstract

Use of grafts from donation after circulatory death (DCD) as a strategy to increase the pool of transplantable livers has been limited due to poorer recipient outcomes compared with donation after brain death (DBD). We examined outcomes of recipients of failed DCD grafts who were selected for relisting with regard to waitlist mortality and patient and graft survival after retransplant. From the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database, we identified 1820 adults who underwent first deceased donor liver transplant January 1, 2004 to June 30, 2011, and were relisted due to graft failure; 12.7% were DCD recipients. Compared with DBD recipients, DCD recipients had better waitlist survival (90-day mortality: 8%, DCD recipients; 14–21%, DBD recipients). Of 950 retransplant patients, 14.5% were prior DCD recipients. Graft survival after second liver transplant was similar for prior DCD (28% graft failure within 1 year) and DBD recipients (30%). Patient survival was slightly better for prior DCD (25% death within 1 year) than DBD recipients (28%). Despite higher overall graft failure and morbidity rates, survival of prior DCD recipients who were selected for relisting and retransplant was not worse than survival of DBD recipients.

Abbreviations

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- DBD

-

- donation after brain death

-

- DCD

-

- donation after circulatory death

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- HR

-

- hazard ratio

-

- MELD

-

- Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

-

- OPTN

-

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

-

- SRTR

-

- Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

Introduction

Although liver transplant outcomes have improved significantly over the past decades, organ shortage remains a major problem; in the recent past, more than 12 000 patients were waiting for an organ at any given time 1. In 2003, federal policies endorsed increasing the use of donation after circulatory death (DCD) as a strategy to enlarge the donor pool 2. Consequently, the proportion of DCD donors surged from 1.6% in 2002 to 5.2% in 2007 3. However, enthusiasm was tempered around 2007 after a growing body of evidence indicated that transplant outcomes after DCD were inferior compared with outcomes of grafts obtained from donation after brain death (DBD), and the number of DCD transplants has been stagnant since 1, 4.

DCD grafts are procured after a variable period of ischemia following withdrawal of life support; hence, they are prone to ischemic cholangiopathy, reported in 15–37% of patients 5, 6, and subsequent nonanastomotic biliary strictures or biliary cast syndrome 7-9. Consequently, DCD transplants are associated with higher morbidity, longer hospital stays, increased costs 10, higher graft failure rates and higher mortality 11. Simultaneous with documentation of these limitations of DCD grafts, discard rates of DCD livers have increased in recent years. Between 2004 and 2010, the proportion of discarded livers that were DCD livers increased from 8.7% to 28.4%, a fourfold increase in a multivariable analysis 4.

Although the extent to which this rising trend of discarded DCD livers is attributable to concerns about their inferior outcomes is unclear, DCD remains the fastest growing potential source of transplanted livers. Clearly, appropriate use of DCD livers should be encouraged to increase the number of transplantable organs. A strategy to achieve that end may involve granting exception scores to recipients of DCD livers that fail, in order to facilitate retransplant and remove disincentives to use DCD livers 6, 8, 12. Ideally, such a policy should be based on an objective analysis that accounts for not only rates of graft failure and patient survival after DCD transplant, but also associated morbidity leading to suffering and poor quality of life. However, as the current guiding principle for liver allocation is risk of mortality, the extent to which patient morbidity and poor quality of life may be considered in transplant allocation remains uncertain. An important barrier to this consideration is lack of data that allow appropriate translation between quantity and quality of life in DCD recipients whose grafts are failing. While morbidity data continue to accumulate for specific patient groups, currently available registry data are the most useful for analyzing mortality data in patients with failed grafts, an integral part in this consideration.

We studied patients who, after receiving a primary DCD graft, experienced graft failure, and were selected to be relisted for repeat transplant, compared with patients who were relisted after failure of DBD grafts. The aims of the study were to compare (i) waitlist mortality after relisting and (ii) graft and patient survival after retransplant. An important caveat of this analysis is that, by definition, it did not include patients with failing grafts who were not re-registered on the waiting list for reasons such as too low a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score or being too sick to be considered for transplant.

Materials and Methods

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, waitlisted candidates and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and has been described elsewhere 13. The Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services, provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.

Study population

The study population included all adults included in the SRTR database who underwent first deceased donor liver transplant between January 1, 2004 and June 30, 2011, and were relisted for graft failure. Recipients of multi-organ transplants were excluded from the analysis.

In analyzing waitlist survival after relisting, we identified DCD and DBD recipients who were registered on the OPTN waiting list after initial graft survival of at least 14 days. This time frame was chosen to eliminate early graft failure from catastrophic events such as primary nonfunction. DBD and DCD graft failure rates are parallel during the first 20 days posttransplant and diverge thereafter; failure rates for DCD grafts continue to increase up to 180 days posttransplant 6. Thus, excluding graft failures in the first 14 days allowed our analysis to reflect the difference in graft failure patterns between the two graft types. Sensitivity analysis including all patients relisted at any time was subsequently performed to evaluate whether the outcomes differed after removing this exclusion criterion. Patients were followed forward from the date of relisting until the first of retransplant, death or study end (November 1, 2011). Deaths that occurred after removal from the waiting list were also counted as deaths. For this analysis, patients were divided into three groups: (i) DCD recipients who were relisted for any reason (DCD group), (ii) DBD recipients who were relisted due to vascular thrombosis or biliary tract complications (DBD-1 group), and (iii) DBD recipients who were relisted for any other reason (DBD-2 group).

The analysis of survival after retransplant included all DCD and DBD recipients who received a second transplant more than 30 days after the primary transplant. Again, this time frame was chosen to eliminate early retransplants in an attempt to focus our analysis on longer-term graft failure from complications such as biliary strictures. Sensitivity analysis including patients who underwent retransplant any time after the initial transplant was subsequently performed. We explored whether outcomes changed over time by comparing outcomes in the first half of the study period (era 1, primary transplant January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2007) with outcomes in the second half (era 2, primary transplant January 1, 2008 through June 30, 2011).

Data analysis

For the waitlist analysis, the outcome of primary interest was 90-day mortality after relisting, censoring retransplants that occurred within 90 days. This time frame was based on the convention of assessing the 90-day waitlist mortality by the MELD score and other indicators of mortality, and on the fact that a majority of waitlist outcomes tend to occur within 90 days. To test the robustness of the results, we conducted sensitivity analysis evaluating waitlist mortality beyond 90 days.

In the analysis of graft and patient survival after retransplant, we examined 1-year mortality. One year is a sufficiently long time interval to allow most influences of pretransplant conditions to materialize. For the graft survival analysis, patients were followed from the second transplant date to the earliest date of all-cause graft failure including death or third transplant. Patient survival was analyzed for the period from the date of the second transplant to death.

Survival was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression models adjusted for covariates were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for patient and graft survival for DCD and DBD recipients. The covariates considered for model adjustment consisted of variables included in risk-adjustment models for 1-year adult graft survival for the liver program-specific reports. They included donor characteristics: age, height, race/ethnicity, ABO compatibility, malignancy, hepatitis C virus (HCV), metabolic disease, history of cancer, cocaine use, hypertension, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention high-risk indicator, receipt of inotropic agents, desmopressin and diuretics; recipient characteristics: age, race/ethnicity, albumin, international normalized ratio, creatinine, receipt of dialysis, life support, split/partial graft, functional status, medical condition, portal vein thrombosis, previous abdominal surgery, previous liver transplant, previous malignancy and insurance coverage; and transplant characteristics: donor and recipient geography, cold ischemia time and interaction between diagnosis of HCV by donor age. Backward variable selection with p-value = 0.10 was employed to limit the model to relevant covariates.

Results

Waitlist survival after graft failure in DCD versus DBD recipients

In all, 1820 patients were included in the analysis; 231 (12.7%) were previous DCD recipients, 428 (23.5%) DBD-1 patients, and 1161 (63.8%) DBD-2 patients. Table 1 compares the characteristics of the three groups. Notably, DCD recipients overall were listed with lower biological MELD scores than their counterparts (approximately 58% of DCD recipients were relisted with MELD scores < 20, compared with 48% of DBD-1 and 35% of DBD-2 patients). Similarly, DBD recipients were likely to need life support and hemodialysis and to display poorer functional status than DCD recipients. Comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hepatocellular carcinoma, or increased albumin levels did not differ significantly between the three groups (data not shown).

| Characteristics | Study group | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCD | DBD-1 | DBD-2 | ||

| n | 231 | 428 | 1161 | |

| Age (year) | 52.5 (10.1) | 51.4 (10.5) | 50.5 (10.6) | 0.01 |

| Height (cm) mean (SD) | 172.9 (11.2) | 173 (10.1) | 173 (10.6) | 0.91 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.18 | |||

| White | 163 (70.6) | 318 (74.3) | 791 (68.1) | |

| Black or African American | 6 (2.6) | 12 (2.8) | 32 (2.8) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 24 (10.4) | 39 (9.1) | 167 (14.4) | |

| Asian/Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 36 (15.6) | 53 (12.4) | 154 (13.3) | |

| Multi-racial/American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.9) | 6 (1.4) | 17 (1.5) | |

| Time from original transplant to relisting (month)1 | 9.7 (13.0) | 8.2 (11.3) | 16.1 (17.8) | <0.01 |

| Medical urgency status at listing | <0.012 | |||

| Status 1/1A | 6 (2.6) | 19 (4.4) | 44 (3.8) | |

| MELD 6–103 | 15 (6.5) | 39 (9.1) | 75 (6.5) | |

| MELD 11–143 | 34 (14.7) | 60 (14.0) | 92 (7.9) | |

| MELD 15–203 | 81 (35.1) | 97 (22.7) | 226 (19.5) | |

| MELD 21–303 | 64 (27.7) | 134 (31.3) | 395 (34.0) | |

| MELD 31–403 | 31 (13.4) | 79 (18.5) | 329 (28.3) | |

| Serum creatinine | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.4 (1) | 1.4 (1) | 0.37 |

| Hepatitis C virus | 108 (46.8) | 175 (40.9) | 670 (57.7) | <0.01 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 75 (32.5) | 109 (25.5) | 305 (26.3) | 0.12 |

| Dialysis 2 times/week in prior week | 5 (2.2) | 19 (4.4) | 67 (5.8) | 0.06 |

| On life support | 7 (3.0) | 23 (5.4) | 83 (7.2) | 0.04 |

| Functional status | 0.01 | |||

| No assistance | 125 (54.1) | 209 (48.8) | 585 (50.4) | |

| Some assistance | 59 (25.5) | 96 (22.4) | 230 (19.8) | |

| Total assistance | 36 (15.6) | 98 (22.9) | 238 (20.5) | |

| Missing | 11 (4.8) | 25 (5.8) | 108 (9.3) | |

| Portal vein thrombosis prior to primary transplant | 11 (4.8) | 42 (9.8) | 55 (4.7) | <0.01 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 82 (35.5) | 159 (37.2) | 386 (33.3) | 0.33 |

| Donor age (year) | 39.5 (14.5) | 48.2 (17.1) | 48.2 (17.7) | <0.01 |

| Donor race/ethnicity | <0.01 | |||

| White | 195 (84.4) | 259 (60.5) | 741 (63.8) | |

| Black or African American | 18 (7.8) | 101 (23.6) | 202 (17.4) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 16 (6.9) | 53 (12.4) | 179 (15.4) | |

| Asian/Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2 (0.9) | 11 (2.6) | 33 (2.8) | |

| Multi-racial/American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 4 (0.9) | 6 (0.5) | |

| Donor and candidate geography | 0.14 | |||

| In same OPO | 137 (59.3) | 285 (66.6) | 783 (67.4) | |

| In same region but not same OPO | 67 (29.0) | 109 (25.5) | 270 (23.3) | |

| Not in same region or OPO | 27 (11.7) | 34 (7.9) | 108 (9.3) | |

| Partial or split liver | 0 | 5 (1.1) | 12 (1) | 0.28 |

| Cold ischemia time (h) | 0.03 | |||

| Less than 9 | 151 (65.4) | 274 (64.0) | 787 (67.8) | |

| 9–11 | 39 (16.9) | 83 (19.4) | 227 (19.6) | |

| 12 or more | 20 (8.7) | 48 (11.2) | 75 (6.5) | |

| Missing | 21 (9.1) | 23 (5.4) | 72 (6.2) | |

- Unless otherwise indicated, values are mean (standard deviation) or n (percent).

- DBD-1, donation after brain death recipient relisted due to vascular thrombosis or biliary tract complications; DBD-2, donation after brain death recipient relisted due to any other causes; DCD, relisted donation after circulatory death recipient; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; OPO, organ procurement organization.

- 1 Time to relisting for all patients (including those listed within 14 days) was: DCD, 74 days; DBD-1, 31 days; and DBD-2, 63 days.

- 2 The chi-square test excluded status 1/1A patients.

- 3 Calculated MELD score without additional adjustment or exception points.

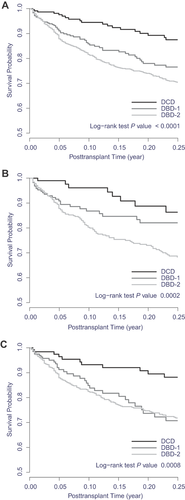

Waitlist outcome data were available for 1722 (95%) of the 1820 included patients; the remainder of patients were administratively censored at study end. Of patients with available waitlist outcome data, 1264 (73.4%) were removed within 90 days after relisting (896 due to transplant, 192 due to death, 176 due to other reasons) and the remaining 458 patients (26.6%) remained on the waiting list for more than 90 days after relisting. Waitlist deaths occurred in 19 DCD recipients (8%), 58 DBD-1 patients (14%) and 240 DBD-2 patients (21%) (Figure 1). DCD recipients survived longer compared with either DBD group (log-rank test p-value < 0.001). Regarding the two eras, waitlist survival rates were poorer in era 2 than in era 1 for DBD-1 patients (those relisted for graft failure due to vascular thrombosis or biliary complications).

Adjusted mortality hazards were significantly higher for both the DBD-1 and DBD-2 groups than for the DCD group (Table 2). Adjusted HRs were 2.32 (95% CI 1.36–3.97) for the DBD-1 group and 2.88 (95% CI 1.77–4.67) for the DBD-2 group. Other variables affecting waitlist mortality included recipient age, HCV diagnosis, renal function, functional status and cold ischemic time. Results of the waitlist mortality analysis extended beyond 90 days did not change: HRs were 2.07 (95% CI 1.36–3.15) for the DBD-1 group and 2.44 (95% CI 1.70–3.51) for the DBD-2 group. When the study period was split into two eras, waitlist survival remained better for DCD versus DBD-1 recipients (HRs 1.77 for era 1 and 2.92 for era 2) and DBD-2 recipients (HRs 2.54 for era 1 and 3.17 for era 2).

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| DBD-1 (ref: DCD) | 2.32 (1.36–3.97) | <0.01 |

| DBD-2 (ref: DCD) | 2.88 (1.77–4.67) | <0.01 |

| Cold ischemia time | ||

| 9–11 h | 0.72 (0.53–0.99) | 0.04 |

| ≥12 h | 0.83 (0.53–1.30) | 0.42 |

| Diagnosis of HCV | 1.40 (1.10–1.78) | <0.01 |

| Functional status | ||

| Some assistance | 1.36 (1.01–1.84) | 0.04 |

| Total assistance | 1.52 (1.12–2.07) | <0.01 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1.44 (0.94–2.20) | 0.10 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 1.27 (1.00–1.61) | 0.048 |

| Candidate age at first transplant (year) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <0.01 |

| Candidate height (cm) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.07 |

| Candidate race (ref: White) | ||

| Black or African American | 0.80 (0.37–1.74) | 0.57 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.74 (1.27–2.39) | <0.01 |

| Asian | 0.98 (0.70–1.37) | 0.89 |

| Candidate serum creatinine (ln) | 1.26 (1.02–1.57) | 0.03 |

| Candidate dialysis (2×/week) in prior week | 1.68 (1.09–2.59) | 0.02 |

- CI, confidence interval; DBD-1, donation after brain death recipient relisted due to vascular thrombosis or biliary tract complications; DBD-2, donation after brain death recipient relisted due to any other causes; DCD, relisted donation after circulatory death recipient; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HR, hazard ratio; ln, natural logarithm.

- 1 All patient characteristics included in risk-adjustment models for 1-year adult graft survival for the liver program-specific reports were considered for model adjustment.

Sensitivity analysis of all relisted patients (after removing the exclusion criterion of the first 14 days after primary transplant) included an additional 97 DCD, 222 DBD-1 and 708 DBD-2 recipients. Compared with failed DCD grafts, waitlist mortality risk for the DBD-1 group remained higher but was no longer significant (HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.76–1.67), while that of DBD-2 group remained significantly higher (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.33–2.56).

Patient and graft survival after second liver transplant

Of 950 patients included in the survival analysis following retransplant, 138 (14.5%) were DCD recipients and 812 (85.5%) were DBD recipients. The DCD patients had lower biological MELD scores, better functional status, fewer HCV diagnoses, and less intensive unit care, and they required less life support (Table 3). In contrast, although the differences were not statistically significant, DBD recipients seemed to receive better retransplant donor organs (less cold ischemia time; less donor history of cancer, hypertension, or desmopressin use; more local donors).

| Characteristics | Recipients | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCD | DBD | ||

| n | 138 | 812 | |

| Recipient age (year) | 52.3 (10.1) | 51.6 (10.1) | 0.38 |

| Recipient height (cm) mean (SD) | 172.9 (11.2) | 173.4 (11.1) | 0.91 |

| Recipient race/ethnicity | 0.15 | ||

| White | 100 (72.46) | 593 (73.0) | |

| Black or African American | 2 (1.45) | 23 (2.8) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12 (8.70) | 96 (11.8) | |

| Asian/Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 24 (17.39) | 92 (11.3) | |

| Multi-racial, American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 8 (1.0) | |

| Time between first and second liver transplant (month) | 13.6 (15.2) | 15.6 (16.7) | 0.17 |

| Medical urgency status at second liver transplant | <0.011 | ||

| Status 1/1A | 1 (0.7) | 31 (3.8) | |

| MELD 6–102 | 9 (6.5) | 49 (6.0) | |

| MELD 11–142 | 11 (8.0) | 47 (5.8) | |

| MELD 15–202 | 35 (25.4) | 113 (14.0) | |

| MELD 21–302 | 58 (42.0) | 305 (37.6) | |

| MELD 31–402 | 24 (17.4) | 267 (32.8) | |

| Recipient serum creatinine—mean (SD) | 1.5 (1) | 1.7 (1.1) | <0.01 |

| Recipient INR—mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.8) | <0.01 |

| Recipient albumin—mean (SD) | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.7) | 0.08 |

| Recipient diagnosis of hepatitis C | 35 (25.4) | 306 (37.7) | <0.01 |

| Recipient metabolic liver disease | 10 (7.3) | 23 (2.8) | 0.02 |

| Recipient dialysis 2 times/week in prior week | 6 (4.4) | 83 (10.2) | 0.04 |

| Recipient in intensive care unit | 12 (8.7) | 175 (21.6) | <0.01 |

| Recipient on life support | 3 (2.2) | 92 (11.3) | <0.01 |

| Recipient functional status | 0.02 | ||

| No assistance | 44 (31.9) | 208 (25.6) | |

| Some assistance | 42 (30.4) | 183 (22.5) | |

| Total assistance | 48 (34.8) | 378 (46.6) | |

| Missing | 4 (2.9) | 43 (5.3) | |

| Recipient previous portal vein thrombosis | 5 (3.6) | 70 (8.6) | 0.07 |

| Donor age (year) | 40.0 (15.3) | 36.9 (15.4) | 0.03 |

| Donor risk index | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.3) | 0.06 |

| Donor race/ethnicity | 0.68 | ||

| White | 92 (66.7) | 508 (62.6) | |

| Black or African American | 21 (15.2) | 167 (20.6) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 19 (13.8) | 109 (13.4) | |

| Asian/Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 5 (3.6) | 24 (3.0) | |

| Multi-racial, American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.7) | 4 (0.5) | |

| Donor received desmopressin | 34 (24.6) | 156 (19.2) | <0.01 |

| Donor and recipient geography | 0.62 | ||

| In same OPO | 92 (66.7) | 569 (70.1) | |

| In same region but not same OPO | 38 (27.5) | 208 (25.6) | |

| Not in same region or OPO | 8 (5.8) | 35 (4.3) | |

| Second liver transplant with DCD | 1 (0.7) | 12 (1.5) | 0.76 |

| Partial or split liver | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 1.00 |

| Cold ischemia time (h) | 0.53 | ||

| Less than 9 | 89 (64.5) | 574 (70.7) | |

| 9–11 | 29 (21.0) | 139 (17.1) | |

| 12 or more | 10 (7.3) | 47 (5.8) | |

| Missing | 10 (7.3) | 52 (6.4) | |

- Unless otherwise indicated, values are mean (standard deviation) or n (percent).

- DBD, donation after brain death; DCD, donation after circulatory death; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; OPO, organ procurement organization.

- 1 The chi-square test excluded status 1/1A patients.

- 2 Calculated MELD score without additional adjustment or exception points.

We sought to determine the degree to which MELD exception scores at retransplant influenced graft allocation for DCD and DBD recipients. The distribution of biological and match MELD scores for the two groups are listed in supplementary Table S1. Compared with DBD recipients, more DCD recipients received exception scores at retransplant, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (17% vs. 24%, p = 0.07). However, comparing the means and distributions of additional MELD exception scores, DBD recipients received more MELD exception points than DCD recipients (mean additional points, 14.9 and 11.3, respectively).

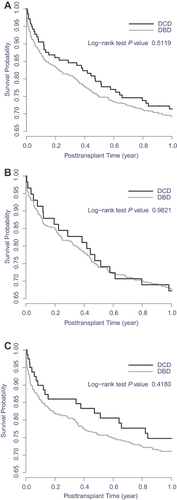

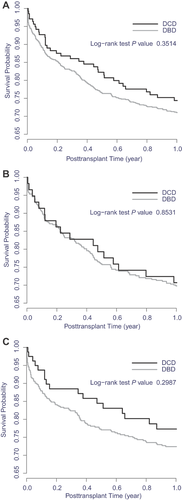

Graft survival after second liver transplant was comparable for prior DCD recipients (28% graft failures) and prior DBD recipients (30% graft failures; Figure 2). Patient survival after retransplant was also similar in the two groups (Figure 3). Retransplant recipient survival was slightly better when the initial graft was from DCD (25% of initial DCD recipients died) than when it was from DBD (28% of initial DBD recipients died), with the trend more notable more recently. After adjustment for relevant covariates, a primary DCD graft had no effect on survival of the second graft (HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.73–1.49, p = 0.81; Table 4) or the patient (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.65–1.40, p = 0.80; Table 5).

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Primary transplant donor type: DCD (ref: DBD) | 1.04 (0.73–1.49) | 0.81 |

| Diagnosis of HCV | 1.30 (1.02–1.66) | 0.03 |

| Recipient metabolic liver disease | 2.08 (1.22–3.54) | <0.01 |

| Donor age (year) | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.12 |

| Donor received desmopressin | 0.65 (0.47–0.90) | <0.01 |

| Regional sharing | 1.29 (1.00–1.68) | 0.05 |

| National sharing | 2.09 (1.32–3.31) | <0.01 |

| Functional status | ||

| Some assistance | 1.86 (1.25–2.78) | <0.01 |

| Total assistance | 2.01 (1.39–2.92) | <0.01 |

| Recipient in intensive care unit | 1.83 (1.31–2.56) | <0.01 |

| Recipient age (year) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.06 |

| Recipient albumin (ln) | 0.68 (0.43–1.07) | 0.09 |

| Recipient life support | 1.57 (1.06–2.33) | 0.02 |

- CI, confidence interval; DBD, donation after brain death; DCD, donation after circulatory death; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HR, hazard ratio; ln, natural logarithm.

- 1 All patient characteristics included in risk-adjustment models for 1-year adult graft survival for the liver program-specific reports were considered for model adjustment.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Primary transplant donor type: DCD (ref: DBD) | 0.95 (0.65–1.40) | 0.80 |

| Diagnosis of HCV | 1.26 (0.97–1.64) | 0.097 |

| Regional sharing | 1.31 (0.99–1.74) | 0.05 |

| National sharing | 2.12 (1.28–3.51) | <0.01 |

| Recipient age (year) | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.01 |

| Recipient albumin (ln) | 0.62 (0.38–1.01) | 0.05 |

| Recipient height (cm) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.03 |

| Recipient INR (ln) | 1.44 (1.02–2.03) | 0.03 |

| Recipient life support | 2.36 (1.68–3.32) | <0.01 |

- DBD, donation after brain death; DCD, donation after circulatory death; CI, confidence interval; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HR, hazard ratio; INR, international normalized ratio; ln, natural logarithm.

- 1 All patient characteristics included in risk-adjustment models for 1-year adult patient survival for the liver program-specific reports were considered for model adjustment.

In a sensitivity analysis including patients who underwent retransplant at any time (including the first 30 days) after initial transplant, the effect of primary DCD graft on graft and patient survival after retransplant remained nonsignificant (HRs 0.98 and 1, respectively).

Discussion

Previous studies 6, 14, 15, including a recent SRTR analysis 16, have shown that recipients of DCD livers are more likely to experience graft failure than recipients of DBD livers. After adjustment for factors that affect graft survival and other relevant variables, DCD was associated with a 40% increase in graft failure and a 15% increase in death 16. In contrast to the overall outcome after DCD transplant, this analysis, based on patients who were selected to be relisted and undergo retransplant, showed that patient and graft survival was not worse for primary DCD than for primary DBD recipients.

We initially postulated that outcomes may be worse for DCD than for DBD recipients whose grafts fail. However, the results of this analysis indicate that waitlist and postretransplant survival of primary DCD recipients was not inferior to survival of primary DBD recipients once they were relisted or underwent retransplant. In fact, our data show that DCD patients fared better than DBD patients on the waiting list, and this difference seems to have increased in the more recent era. In the multivariable analysis, DBD recipients with vascular or biliary complications were associated with an adjusted HR of 1.8 (p = 0.002) in era 1 (2004–2007), which increased to 2.9 (p = 0.004) in era 2 (2008–2011). A similar trend was seen in the analysis of retransplant outcomes. In multivariable models (Tables 4 and 5), there was no evidence that outcomes after retransplant were inferior for prior DCD recipients compared with prior DBD recipients. Adjusting for covariates in multivariable models tended to increase the HRs associated with prior DCD, consistent with DCD recipients tending to be healthier. While the multiple covariates considered in our multivariable analysis were designed to adjust for systematic differences between the patient categories, those variables may not have identified subtle differences. However, the magnitude of the HRs in the multivariable analyses suggests that it is unlikely that unaccounted variables could negate the observed difference.

A previous analysis by Selck et al 6 showed that failure patterns differ for DCD and DBD grafts. DCD organs tend to fail as a result of biliary and vascular complications via a protracted course of gradual decline in graft function. Patients often endure significant reduction in quality of life due to frequent biliary complications, commonly with percutaneous indwelling biliary drainage catheters, and they often experience recurrent infections and multiple hospitalizations. Unfortunately, these events are not reported in registry databases. Severe hepatic parenchymal malfunction occurs late; hence, MELD scores tend not to reflect the complexity of the morbidity and risk of mortality specific to biliary sepsis. Both our and Selck's analyses showed that DCD retransplant candidates appear less sick at relisting (Table 1). Similarly, at retransplant, DCD recipients had lower frequency of very high MELD scores, better functional status, and lower likelihood of requiring life support or hemodialysis compared with DBD recipients who experience graft failure (Table 3).

One potential limitation of these waitlist analyses is that the threshold at which transplant physicians/surgeons list patients for repeat transplant may differ for prior DCD and prior DBD recipients. Transplant physicians/surgeons may be more aggressive in ensuring that recipients of “marginal” organs initially are given a chance for repeat transplant over recipients of more optimal organs initially. These efforts may be reflected in the proportion of patients who received MELD exception scores, which tended to be more frequent for DCD than for DBD recipients (24% vs. 17%). We emphasize that this analysis included patients who were selected to be relisted and to undergo retransplant; our data should not be extrapolated to all DCD recipients or to DCD recipients with graft dysfunction in general.

Within the current allocation constructs, access to retransplant for patients who receive an organ from a DCD donor may partially compensate for the decreased longevity and the morbidity associated with DCD grafts. A system that incentivizes primary liver candidates to opt for a DCD organ may offer a retransplant soon after the original graft fails and not subject the patient to a long waiting period. While the current analysis of mortality is an important element in this policy consideration, it does not preclude a system that grants exception scores for DCD recipients with graft failure, in recognition of the fact that their acceptance of a DCD organ contributed to expansion of the donor pool and that their morbidity is not taken into account in the current MELD system. We believe that further discussion and exploration of data, including standardized reproducible measures of biliary complications and resulting decreased quality of life and suffering, are needed to consider a system that provides appropriate incentives to increase use of DCD organs while not disadvantaging either DCD or DBD recipients.

In summary, in this analysis of liver transplant recipients who were selected to be relisted and undergo retransplant, waitlist mortality for DCD recipients was not higher than for DBD recipients relisted due to vascular thrombosis, biliary tract complications, or other reasons. On the contrary, there is some evidence that waitlist survival for relisted DCD recipients is better than for relisted DBD recipients. Of patients who received a second graft, prior DCD recipients fared at least as well as prior DBD recipients regarding both graft and patient survival. These results, along with data unavailable in registration data sets, are helpful in policy considerations to promote optimal use of all available organs, including DCD organs.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted under the auspices of the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, as a deliverable under contract no. HHSH250201000018C (US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation). As a US Government-sponsored work, there are no restrictions on its use. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the United States Government. The authors thank Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients colleagues Delaney Berrini, BS, for manuscript preparation and Nan Booth, MSW, MPH, ELS, for manuscript editing.

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.