Mature-Aged People in the Rural Health Workforce System: A Systems Modelling Approach

Funding: This study was supported by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program. J.T. is supported by Australian Research Council FF220100650.

ABSTRACT

Objective

The median age of people in rural areas is older than those living in metropolitan areas. Harnessing the potential of the mature-aged population in rural communities may present a uniquely sustainable approach to strengthening the rural health workforce system. The objective of this study was to map the rural health workforce system in Australia and identify the current and potential role of mature-aged people in the workforce system.

Setting

Not applicable.

Participants

Not applicable.

Design

Systems thinking, specifically causal loop diagramming.

Results

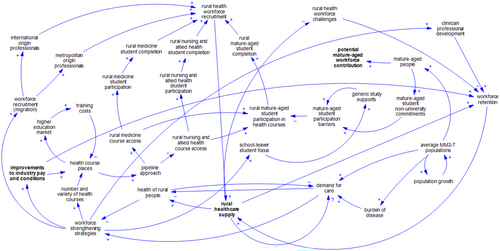

The causal loop diagram illustrates the interrelated variables in the rural health workforce system. It also illustrates that the potential contribution of mature-aged people living in rural communities has been overlooked in the strategies to address the rural workforce undersupply.

Conclusion

Health workforces in regional, rural and remote communities in Australia have experienced constant undersupply despite ongoing government and community effort. Novel approaches are required to determine potential strategies to harness the capacity of rural mature-aged people to strengthen the rural health workforce.

Summary

-

What this paper adds?

- ○

Applies a complexity science tool to the field of rural health.

- ○

Provides a mental model illustrating the variables in rural health workforce in Australia, and how these variables relate.

- ○

Illustrates the untapped capacity of rural mature-aged people in rural health workforce strengthening strategies.

- ○

-

What is already known on this subject?

- ○

Several strategies are used to address the rural health workforce undersupply.

- ○

The median age of rural people is older in rural communities than in metropolitan areas.

- ○

Place-based workforce strategies support sustainable rural health workforce development.

- ○

1 Background

People living in regional, rural and remote Australian communities (rural herein) have, on average, lower life expectancy and increased burden of disease than their metropolitan counterparts [1]. The health of rural people is determined by a number of factors, although timely access to appropriate healthcare services is a significant determinant that continues to impact rural people and communities [2]. An undersupply of health workforces exists in rural communities despite ongoing efforts addressing issues at national, state and local government levels [3]. Healthcare access in rural areas is significantly hampered by workforce undersupply and is of increasing concern for rural communities due to the ageing population [4] and the addition of post-COVID-19 service demands [5].

In Australia, two main strategies are used to address the healthcare workforce undersupply, among others. The first strategy focuses on health workforce importation, where services are delivered to rural people by others not originally from their community. This strategy includes international migration and metropolitan-to-rural migration—the latter often supported via rural work-integrated-learning placements typically engaging metropolitan students [6, 7], the use of visiting professionals [8] and telehealth for offsite provision [9]. The second strategy is the rural health workforce pipeline approach where higher education health courses are made available to rural people so they can successfully complete their study and join the rural health workforce [10]. The latter approach follows recommendations by the World Health Organization [11] to offer health professions education to students with a rural background, to locate this training closer to rural areas and to engage local communities to support student selection.

The pipeline approach should be well positioned to become the main workforce mechanism in Australia. Driven by an equity lens, the Australian Universities Accord Final Report called for an ambitious increase in rural student higher education attainment by 2035 and offered several policy recommendations to support this, including expansion of the Regional University Study Hubs Program, financial supports for health students undertaking compulsory placements and course redesign to support people to take a life-long approach to study [12]. However, given that few rural health academics have shaped the Accord dialogue, there is a risk that initiatives from this review of the higher education system will not benefit the health of rural people and communities [13].

The pipeline approach is not without flaws. Historically, it has focused on the field of medicine and has yet to be fully extended to nursing and allied health, particularly in Australia [14, 15], as illustrated by the relative lack of nursing and allied health courses provided in rural and remote communities [16]. Funding models for supervision of medical students and trainee doctors have varied and at times been inadequate, making it difficult to educate specialist doctors in rural areas [17]. More recently, the Australian Government has provided supervision funding via the Specialist Training Program [18] for specialist trainees. However, in practice, inflexibility in implementation, incompatibility between funding pathways and lack of coverage of full costs limit the ability of rural agencies to adapt to the specific health workforce needs of their communities. The National Rural Generalist Pathway supports end-to-end education for trainee doctors considering rural health as their specialisation, although many other postgraduate specialist training programmes require trainees to attend training for a significant proportion of their training in metropolitan areas, making it difficult to retain medical trainees in rural areas [19]. Furthermore, the pipeline approach largely targets school-leavers [15], who are typically considered to have commenced higher education study at the completion of their secondary education or following a gap year.

Mature-aged people (also referred to as older students in the literature) living in rural communities are an additional cohort that could play a role in addressing the rural health workforce under supply [20]. Rural populations have an older median age than metropolitan populations [21], and indeed, the proportion of mature-aged students increases with rurality [22]. Although there is no universal definition for mature-aged students, Crawford [22] defined mature-aged students as those commencing studies at 21 years of age or older.

Mature-aged students bring particular skill sets to their learning experience that enable them to overcome barriers to study [23]. However, mature-aged students also have non-university commitments unrecognised by universities that can make participation and study completion challenging [24]. A recent study by Quilliam et al. [25] suggests that rural mature-aged health students may not receive the optimal mix or level of support to succeed in their studies because their support needs are often different to that of school-leaver students. Mature-aged students require supports that are age and life-stage appropriate. Additional supports provided to these students need to draw on existing resources within rural communities, including local connections and relationships [25, 26]. It is difficult to predict the potential impact that well-supported rural mature-aged people could have on the development of a rural health workforce without first understanding the health workforce training and recruitment system in which rural mature-aged people might engage. This requires a systems thinking view.

Drawn from complexity science, systems thinking methods are well suited to investigating rural health challenges, including rural health workforce development and sustainability [27]. Systems thinking aims to explore the complex nature of phenomena at higher levels of abstraction that constitute ‘epiphenomena’ (e.g., a health or education system) through understanding the interrelatedness and interactions between system entities and inputs [28]. This contrasts with reductionist approaches that might seek to understand a phenomenon through analysis of its smallest measurable units (e.g., at an atomic level) or as independent units [29]. Despite the utility of methods from systems science approaches in rural health (see Wheaton et al. [30] and Pamungkas et al. [31]), they have not been traditionally used in the field [27]. Systems thinking methods can assist us to understand how issues affecting rural healthcare worker supply might emerge or be reinforced, how they might be ameliorated, or how (and why) interventions might also fail [32].

Causal loop diagrams (CLDs) are a commonly used qualitative method to identify variables and illustrate either established or proposed positive and negative feedback loops within systems [33]. They are tools for thinking that can help to record and describe mental models of how interrelated variables influence each other within a modelled system [34]. CLDs can also be useful in creating initial conceptualisations that can later form the basis of dynamic system representations (system dynamics models) to test hypotheses and calibrate models against the real world. In this regard, relationships between included variables form a set of ‘candidate mechanisms’ by which phenomena (e.g., rural health workforce shortages) may come about. CLDs are well suited to rural health workforce research for several reasons. First, they can help to map out the boundaries of systems in which workforce interventions are designed to operate, assisting users to understand the logic of both primary and secondary envisaged effects of enacted policies and strategies. Second, CLDs suit a participatory approach, providing an opportunity to engage experts who have research, professional and/or lived experience of a system's dynamics, to ensure that expertise and experience is faithfully represented [35].

In this paper, we used a CLD with the aim of mapping the rural health workforce training and recruitment regime in Australia and identifying the current and potential role of rural mature-aged people in the system. We aim to identify features of the system that facilitate current recruitment dynamics leading to rural healthcare worker shortages, as well as highlight opportunities for intervention through the recruitment of rurally based mature-aged students.

2 Methods

2.1 CLD Development

The CLD was constructed iteratively via a group modelling process (Sterman, 2000). The CLD team, listed as the author and co-authors, comprised of seven subject matter experts (SMEs), including an experienced health systems modeller, experts on rural health workforce strategy, higher education course selection and development, rural and mature-aged student experiences, and rural health professionals with experience recruiting qualified nursing and allied health professionals to rural health and community services in a large rural town in Victoria, Australia. Involving a range of experts allowed the team to identify diverse variables within the rural health workforce system and the way it interacts with rural mature-aged people. Ethics approval was deemed not required by The University of Melbourne because the development of the CLD did not involve participants or the collection of data.

- Are the variables in the CLD appropriate for our aim?

- Are there any relevant variables not included in the CLD?

- Are the relationships between variables and the direction of the relationships included in the CLD, appropriate?

- Are there any relevant relationships between variables not included in the CLD?

Following the first SME meeting, researcher CQ revised the variables and relationships in line with feedback and overall agreement from the SMEs. In the second meeting, the updated CLD was presented to the SMEs and they were asked for reflections on the model. Discussion during this workshop resulted in a recommendation to making minor changes to the CLD, including a variable around changing industry pay and conditions as a policy response, and the inclusion of an unknown polarity relationship between rural healthcare supply and demand for care. In the third meeting, there was SME agreement that the CLD largely reflected the rural health workforce system. The final CLD was constructed using software Vensim [38]. In the fourth meeting, the team made final minor changes to the variables, including variable names and their descriptions, and agreed to the final version of the CLD. The team also identified the problem statement arising from reflections on the CLD.

3 Results

The CLD of the rural health workforce system in Australia is presented in Figure 1, as are the proposed variables and relationships between these variables. Consistent with the ‘causal’ language ethos of CLD, results are described in a causal manner. We emphasise, however, that the model consists only of hypothesised relationships that the SME team suggests may be true but have not been empirically validated in this work. We encourage the reader to consider the results of the model with this interpretation in mind; that is, we aim to describe the causal relationships in the model and hypothesise that these relationships map onto the real world.

As illustrated, SMEs agreed that the population growth of regional, rural, and remote populations and the increased burden of disease within this population leads to increased demand for care and reduced health of rural people. When rural people experience relatively ‘good’ health, there is less imperative to improve the rural workforce, and therefore, the focus on developing strategies to strengthen the rural health workforce decreases. This includes the decreased emphasis on targeted workforce recruitment of international and metropolitan-origin health professionals to rural areas, and professional development for clinicians seeking career advancement. Another workforce strengthening strategy includes improvements of health industry pay and conditions, which may increase the incentive to join the workforce, create health course place uptake in rural areas and positively impact workforce retention. The number and variety of healthcare industry courses increases health course places in rural areas, strengthens the higher education market and increases total training costs. An increase in training costs then reduces the number of available health course places in a balancing (negative feedback) loop. Rural health course places increase the number of students in the pipeline approach, where courses are delivered to rural people in rural communities. The pipeline approach prioritises access to medicine courses in rural areas, which results in increased participation of medical students in rural courses, medical student completion and rural health workforce recruitment. The prioritisation of medicine course delivery in rural areas means less attention to nursing and allied health courses in rural areas. The provision of nursing and allied health courses in rural areas results in nursing and allied health student participation and completion, and rural health workforce recruitment. As rural people's access to medicine, and nursing and allied health courses increases, the participation of rural mature-aged people in courses increases, which in turn drives mature-aged student completion of health courses and rural health workforce recruitment.

A further workforce strengthening strategy is to focus on school-leaver students (aged 20 years or younger on course enrolment) as the primary cohort for the rural healthcare workforce. This focus on school-leaver students requires an increase in availability of generic study supports for students by universities, rather than those that are tailored for particular student cohorts, including mature-aged students (aged 21 years or older on course enrolment). A focus on generic study supports increases barriers for mature-aged people to participate in university health courses.

The rural health workforce is developed via several strategies, including international and metro-origin professional recruitment, retention through clinician professional development, and rural medicine, nursing and allied health student participation in preregistration courses. The recruited health workforce increases rural healthcare supply. The rural healthcare supply increases workforce retention and reduces rural health workforce challenges (such as lacking professional development opportunities, burnout, peer and collegial support, poor housing, and poor belonging-in-place for metro and international origin staff). Workforce challenges reduce workforce retention. Workforce retention leads to increased rural healthcare supply. The relationship between rural health supply and demand for care is complex, as demand for care is determined by population growth, burden of disease and the health of rural people.

The higher proportion of mature-aged people in rural populations may produce a higher proportion of students with mature-aged related non-university commitments and an increase in the potential for mature-aged people to contribute to the rural health workforce, although this potential is not realised. Rather, an increase in non-university commitments, combined with the provision of generic study supports, which do not adequately meet the needs of mature-aged students, leads to further participation barriers for rural mature-aged students.

The CLD suggests that strategies to: (i) support recruitment via international and metropolitan migration to rural communities and retention through professional development opportunities, and (ii) prioritise medical and school-leaver students in rural communities to access, participate and complete health courses, play a significant role in the effort to strengthen the rural workforce in Australia. However, current efforts do not emphasise mature-aged people and therefore do not harness the potential capacity of a range of mature-aged people in rural communities to contribute to the rural healthcare supply.

- Strategies aimed at strengthening the current rural health workforce do not fully address the rural health shortages in regional, rural and remote Australian communities. These communities continue to experience health professional shortages and, in turn, poor health service access.

- A focus in higher education on school-leaver students may contribute to poorer support for rural mature-aged people to join the rural health workforce, reinforcing existing rural health workforce supply issues.

4 Discussion

A CLD was used to map the rural health workforce system in Australia and identify the potential role of rural mature-aged people in the system as a partial solution to rural health workforce shortage issues. The CLD suggests that current workforce strengthening strategies to meet demand for health care in rural areas are complex and interconnected but could be improved through consideration of the entire pool of potential workforce contributors, including rural mature-aged people.

The process of developing the CLD generated discussion among the SMEs on the nuances within mature-aged populations in rural communities. Rural mature-aged people are a heterogenous group, diverse in age, life and work experience, and skills and knowledge [39]. This diversity sits in contrast to school-leaver students, who have had less time and opportunity to gather responsibilities alongside a range of life and work experiences. Mature-aged people may fit into several prospective rural health workforce sub-cohorts: for example, those who have previously worked in the health field, those that currently work in the health field and those who have not worked in health but may have other relevant work or life experience. These sub-groups are likely to require varying supports to join the workforce that acknowledge and accommodate this heterogeneity and supports that are presently uncertain [20]. The workforce recruitment of mature-aged people has received increased attention in recent years, due to ageing populations and the impact of COVID-19 on employment patterns [40]. Further research is required to understand how rural health and human services currently consider heterogeneity in the mature-aged population during recruitment, and how these processes can be improved. For instance, how do the skills and experiences of mature-aged people impact their pathway into the industry? How can rural health and human services better accommodate for the skills and experience of prospective rural mature-aged people? Recent higher education policy discussion in Australia suggests innovation is required to support the connection between life-long learning and employment, particularly in rural areas [12].

Another significant issue raised through the CLD development and its requirement to explicitly define the structure of the system was the effect of pay conditions and competition in the health and human services sector on the retention of health professionals in rural areas (See Figure 1). Modelled improvements in industry pay have been proposed to positively impact job satisfaction and also workforce retention [41], and financial incentives have been considered important for rural health workforce retention for some time [42, 43]. However, rural mature-aged people have financial commitments and additional costs that may impact their decision to undertake or continue their studies to join the chosen workforce [20, 26]. The undersupply and demand for rural health professionals in rural areas means that health services often draw from the same pool of local people as potential employees. This leads to a level of competition and ‘poaching’ of staff between organisations in smaller communities [44]. Accounting for the more relational nature of rural communities when compared with urban counterparts [45], it is possible that rural health service managers draw on relationships with other managers to reveal knowledge about the capacity of and previous work undertaken by potential employees. This relational element places rural mature-aged students in a different situation to rural school-leaver students, where their work experience may inform their post-graduation employment. Improvement in pay and other employment conditions are important, particularly for utilising the potential of the prospective rural mature-aged cohort. However, innovative workforce strategies are needed to expand the rural health workforce to reduce unproductive competition between rural health services and ensure rural health service demands are met in a sustainable manner.

The systems thinking approach employed here has been helpful for understanding the variables involved in the rural health workforce system and the relationships between these variables. The variables and relationships between variables proposed in this model could be further explored using systems thinking to understand the role of rural mature-aged people in the development of the rural health workforce. For example, the capacity of rural mature-aged populations in hypothetical rural communities to contribute to the rural healthcare workforce supply could be examined via systems dynamics modelling, drawing on variables such as the eligible mature-aged population, higher education attainment rates and workforce retentions rates. In such a study, a model would be constructed and a stock and flow approach used to align and observe variable interactions, drawing on existing data [38]. This type of study may identify rural health workforce strengthening strategies worthy of investment and, importantly, could test the assumptions made in the current, static representation through model verification processes, and the collection of empirical evidence to validate proposed causal relationships [46]. These aspects of verification and validation will be crucial to the construction of future iterations of the proposed model.

4.1 Conclusion

The saying goes that ‘all systems are perfectly designed to produce the results they get’, and rural health workforces are no exception. The rural health workforce regime in Australia comprises a set of interrelated entities and inputs that work to generate a shortage of healthcare workers in rural locations. Although a range of workforce strengthening strategies are in place to address the undersupply of rural health professionals in rural areas, further innovation is required to ensure rural people have access to health professionals and health services. Our discussions indicate that mature-aged people in rural communities are a cohort that could be utilised to strengthen the regional, rural and remote health workforce in Australia.

Author Contributions

C.Q., J.T., N.C., C.M., A.C., R.B. and L.S. made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work, drafted the work, revised it critically for important intellectual content, contributed to the final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics Statement

Ethics approval was deemed not required by The University of Melbourne because the development of the CLD did not involve participants or the collection of data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.