Barriers and enablers to accessing perinatal health services for rural Australian women: A qualitative exploration of rural health care providers perspectives

Abstract

Objective

To identify perceived barriers and enablers for rural women in accessing perinatal care within their own community from the perspective of perinatal health care providers.

Design

A qualitative descriptive study design utilising reflexive thematic analysis, using the socioecological framework to organise and articulate findings.

Setting

Victoria, Australia.

Participants

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine perinatal health care providers who provide care to pregnant women or new mothers in rural communities. Participants were recruited across Victoria in 2023.

Results

Providers reported multi-level barriers and enablers that exist for rural women in accessing perinatal care within their communities. Barriers included women's personal circumstances, challenging professional relationships, inequitable service provision, ineffective collaboration between services and clinicians and government funding models and policies. Enablers included strength and resilience of rural women, social capital within rural communities, flexible care delivery and innovative practice, rural culture and continuity of care models.

Conclusion

Rural perinatal health care providers perceived that rural women face multiple barriers that are created or sustained by complex interpersonal, organisational, community and policy factors that are intrinsic to rural health care delivery. Several addressable factors were identified that create unnecessary barriers for rural women in engaging with perinatal care. These included education regarding health systems, rights and expectations, equitable distribution of perinatal services, improved interprofessional relationships and collaborative approaches to care and equity-based funding models for perinatal services regardless of geographical location.

What is already known about this subject

- Rural women and their infants continue to experience poorer perinatal outcomes than their urban counterparts.

- Rural women face challenges in accessing perinatal care close to their homes, when compared to women living in urban environments, primarily due to increasing service closures and persistent workforce crises.

What this paper adds

- This paper identifies barriers and enablers that exist for rural women in accessing perinatal care from the perspective of the perinatal health care providers.

- This paper articulates multifaceted influences at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy levels. Several addressable factors are identified that create unnecessary barriers for rural women in engaging with perinatal care.

1 INTRODUCTION

Australia is a vast continent,1 and delivery of equitable health care to geographically diverse rural and remote populations is challenging.2 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare considers ‘rural and remote’ to be all populations outside Australia's major cities.2 The geographically diverse population results in disparate access to services rural and remote Australians, who comprise 28.2% of the entire population.2-4 In addition, the life expectancy of Australians living in rural areas are lower than Australians living in urban areas, and they experience higher rates of potentially avoidable deaths and potentially preventable hospitalisations.2 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data from 2018 confirm that the burden of disease (i.e., the quantified impact of a disease or injury on a population, which captures overall health loss) increases with increasing remoteness for rural Australians with the ABS acknowledging that rural and remote Australians face barriers to accessing health care, related to the influence of geographic spread, low population density, limited infrastructure and the higher costs of delivering rural and remote health care.2

This inequity with respect to health care and health outcomes is also experienced by rural women and their infants, who have been shown to experience poorer birth outcomes than those living in urban environments.5 Rural women are more likely to experience haemorrhage after birth or be admitted to ICU.5 Infants born to rural or remote mothers are at greater risk of being born preterm, being born low birthweight, have a low Apgar score (a measure of neonatal well-being at birth) at 5 min or be admitted to a special care nursery (SCN) or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).6

Rural women face unique challenges with respect to the ‘rural determinants of health’, which incorporate the issues of geography and isolation in addition to economic, social and political influences that act together to strengthen or undermine the health and well-being of individuals and communities.7, 8 This impact is further compounded by the inequitable distribution of social disadvantage amongst rural communities, with rural and remote Australians experiencing lower levels of education, higher rates of unemployment and lower income levels than people living in urban areas.2 In addition, ‘the inverse care law’ exists for vulnerable populations, whereby those who could benefit from health care the most are least likely to receive it, further perpetuating poorer health outcomes.9 Understanding the barriers that rural women and their families face in accessing perinatal care is critical to developing strategies to mitigate addressable factors and reduce the impact of the rural determinants of health. The perceptions of perinatal care providers of the barriers and enablers to accessing care for rural women have not been examined and as key providers and stakeholders in rural perinatal health care, the value of exploring these perceptions is advantageous to health services and policy developers. This study aimed to identify barriers and enablers for rural women in accessing perinatal care from the perspective of the health care providers with a focus on identifying addressable factors.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

We employed a qualitative descriptive study design utilising reflexive thematic analysis to identify, analyse and interpret ‘themes’ in the data.10 Qualitative description seeks to examine a phenomenon in its natural state, drawing from a naturalistic perspective, which enables the researcher to stay close to the data and its intended meaning at every stage.11 Reflexive thematic analysis was considered the most appropriate method to enable organic theme development, affording flexibility in identifying patterns in relation to the views, perceptions and lived experiences of the participants whilst also acknowledging the role of the researcher subjectivity/reflexivity in knowledge generation10 The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) checklist was used to guide the quality of reporting.12

2.2 Setting

This study was conducted in the state of Victoria, Australia, in rural and regional areas. Health care in Australia is state and nationally funded through Medicare (General Practice and primary health care services) and state-run public health services.13 Victorian maternity care is delivered through a number of different models largely dependent on location, workforce and health service priorities.14 In 2023, there were just over 1000 models of care in use across the nation (across 251 maternity services); however, 81% of the models consist of four model categories—public hospital maternity care (41% of models), shared care (15%), midwifery group practice caseload care (14%) and private obstetrician specialist care (11%).15 Rural women have access to fewer options in terms of maternity models of care compared with women who live in urban areas due to workforce, funding and service structure restrictions existing in rural communities.16 Rural health services operate via a devolved governance framework in which health services determine their own operational and funding priorities driven by local strategic priorities and the ‘statement of priorities’ (issued by the state Government).17 Whilst this provides an opportunity for contextual health service planning based on community need, this model can create inequitable distribution of resources and services due to reliance upon leadership that is informed and committed to providing maternity services.16

2.3 Reflexivity statement

Reflexivity involves not only interrogating one's own social location and its impact on the research but also examining positionality and being cognisant of the shifting power relations that exist between researcher and participant.18 The first author is a female who has been a registered midwife for over 30 years. She has worked in small rural, large regional and metropolitan maternity services and has personal experience of pregnancy and birth in a rural community. Reflexivity was addressed through the methods of this study and in the constant examination of assumptions being made during the interpretation and coding of data.

2.4 Participants

Health professionals were considered ‘perinatal health care providers’ in this study if they provided care for a woman and her newborn during pregnancy, labour and birth or the postnatal period for conditions related to the pregnancy or birth. Primary providers of perinatal health care in rural Victoria are general practitioners (or general practitioner obstetricians), registered midwives, Maternal and Child Health Nurses (MCHNs), lactation consultants and perinatal mental health clinicians (nurses, psychologists and psychiatrists).

Rurality was determined through the Modified Monash Model (MMM) and communities were considered rural if they were MMM3 (large rural town), MMM4 (medium rural town) or MMM5 (small rural town).19 There were no participants from remote (MMM6) or very remote (MMM7) communities.

2.5 Recruitment

A purposive sampling approach was used to ensure a diverse group of participants were recruited with respect to area of perinatal clinical practice, and region. Participants were recruited through unpaid social media advertisements (via Twitter, LinkedIn and Facebook). Participants could express their interest in participating by following a link on the advertisement to a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)20 page to complete a set of eligibility screening questions, read the participant information and give consent to participate. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform to support data capture for research studies.20 Participants were asked some demographic questions about their profession, postcode, the type of perinatal care they provide, their age (in 10-year interval categories, i.e., 40–49) and the number of years that they have been providing perinatal care to rural women (in 5-year interval categories, i.e., 6–10 years). Participants who consented to participate were contacted via email by the first author to schedule an interview at a time that suited them.

2.6 Data collection

Interviews were conducted between February and April 2023 by the first author with experience and training in qualitative inquiry. We developed an interview schedule (Table 1) based on clinical experience and current evidence on perinatal care provision in rural and remote communities in high income nations.16, 21, 22 The interview schedule was piloted with a rural perinatal health care provider (midwife) and minor changes to content, and format were made based on feedback provided. A total of 12 rural perinatal health care providers read the participant information and provided their consent to participate. Two health care providers did not respond to requests for scheduling of interviews, and contact was ceased after four attempts to arrange an interview. One was unable to participate due to extended leave. Interviews were conducted via a virtual platform (Zoom©) by the first author and were audio-recorded with consent of the participants to enable accurate transcription. All participants were alone during the interviews with seven of the participants being interviewed online from their workplace and two being interviewed online from their homes. Audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim by the first author in order to facilitate in-depth familiarisation with the data23 as soon as practicable after the interview and coding commenced soon thereafter. Concurrent transcription and coding of interviews continuously informed sampling until saturation was achieved. Participants were asked at the commencement of the interview if they would like to receive a transcript of the interview, and all accepted this offer. Transcriptions were emailed to all participants; however, only two participants elaborated on some views expressed to ensure accurate interpretation of their meaning. Saturation was determined when no new codes (or themes) had been developed in three sequential transcripts. That is, the themes or sub-themes that had been determined previously were applicable to all elements identified in the subsequent transcripts. This is a widely accepted definition of data saturation in qualitative research.24

| No. | Question | Prompts |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | What is your profession? How long have you been in this role? | |

| 2 | What type of care do you provide to pregnant women or new mothers? | What are the current services provided by the organisation for which you work? Do they provide any specialist services for vulnerable women or women with additional needs? |

| 3 | Can you tell me what it is like being a perinatal care provider in rural Victoria? | |

| 4 | Can you tell me how women living in your community access perinatal care? Are there any challenges in accessing perinatal care? Can you describe these for me in relation to the following services:

|

Any barriers to accessing care? Do you think there are any differences in how women from particular groups (for example, teenage mothers or women from CALD backgrounds) access or experience accessing care? How so? |

| 5 | Can you tell me a little about any differences that may exist for rural women in accessing maternity care compared to women living in a city? | Do you perceive there are any gaps in service provision in rural areas? Is there anything you can think of that may improve access to these services for women living in your community? |

| 6 | Can you describe any benefits or particularly rewarding elements of receiving perinatal care or having a baby in a rural community? | |

| 7 | Do you believe there is anything that would make accessing perinatal care easier or more effective? What do you think that would be? | At a system level, organisational level (how care is organised, including location of services), society level (community perceptions or attitudes), individual level (knowledge, skills, family circumstances, English proficiency) |

2.7 Data analysis

We used reflexive thematic analysis utilising both inductive and deductive approaches to code development and theme identification employing Braun and Clarke's six-phase process for analysis.10, 25 The six phases include data familiarisation; systematic data coding; generating initial themes from coded and collated data; developing and reviewing themes; refining, defining and naming themes; and writing the report.25 A deductive approach to analysis was necessitated by the research question, which inherently provided some direction to the analysis in seeking barriers and enablers to accessing care. A predominantly inductive (or data-driven) approach to coding was utilised, however, whereby codes produced only reflected the content and meaning of the data.26 Reflexive thematic analysis enables an interpretation of qualitative data whilst also acknowledging the subjectivity of the researchers' perspectives and how those perspectives may contribute to interpretation of the data.10 Coding was an iterative process whereby codes were initially identified, utilising a mix of semantic and latent coding, by the first author who had conducted and transcribed the interviews due to intimate and in-depth knowledge of the content and research aims.27 The transcripts were read and re-read to ensure the code development was derived from the data and accurately reflected the context and meaning of the data. Coding involved assigning short phrases or words to segments of data that captured the data's core meaning or significance. For example, the statement, ‘most of the time it's that they possibly couldn't afford to make their own way to the [regional centre]’, was coded to ‘financial resources inhibiting access to perinatal care’. Other members of the research team then coded two of the transcripts based on the developed codes and the applied definitions. Codes were then discussed amongst the team, and some codes were altered slightly to facilitate clarity with respect to their intended meaning. Themes were then developed to summarise the meaning of the codes generated in the initial analysis, with codes being grouped under appropriate themes.10 These were further defined and labelled in discussion amongst authors. Table 2 illustrates the themes with comprised codes. Members of the team refined the code set through further discussion until the final set of codes and themes was agreed upon. QSR International NVivo (version 14) was used for managing the data and generating codes and themes.

| Level | Barriers | Enablers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | Codes | Theme | Codes | |

| Intrapersonal | Personal circumstances |

Social disadvantage or isolation impedes access to perinatal care Financial resources inhibit access to perinatal care Employment conditions impact on access to perinatal care Transportation (routes/modes/cost) prevents access to perinatal care Education and understanding of rights and expectations Family violence/coercive control preventing access to perinatal care |

Strength/resilience |

Rural communities embolden resourcefulness Rural living creates a sense of independence and self-reliance |

| Interpersonal | Challenging interprofessional relationships |

Tensions between professional groups leading to limitations in information provision to women regarding options for care or referral pathways Internal relationships (politics) impacting on workforce and service availability Poor leadership in rural health services can create a toxic work environment and impact on workforce sustainability |

Social capital |

Relationships enabling access to care Relationships supporting transition to motherhood |

| Organisational | Inequitable service provision |

Limited choice of carer due to lack of diversity of models of care Limited choice of services due to service funding priorities Limited service availability due to workforce shortages Restrictive organisational policies that limit choice in accessing different clinicians/models |

Flexible care delivery and innovative practice |

Workforce flexibility increasing availability of services to rural women Flexibility in how care is organised/delivered |

| Community | Ineffective collaboration |

Ineffective systems (siloed, inefficient, fragmented) impeding access to perinatal care Inefficient or unavailable documentation sharing across health services |

Rural culture | Rural culture sustaining the rural workforce, enabling access to perinatal health care providers |

| Policy | Government policy and funding models |

Requirement for GP referral to perinatal care impedes information exchange regarding choices Funding models impede development and sustaining of public antenatal care models Funding models for mental health care impede access for rural women Inadequate funding/resources for rural perinatal care providers Lack of support for digital solutions to enable access to care |

Continuity of care models |

Rural continuity models with care provided by GPO Rural midwifery continuity of care models supported by Executive and Board |

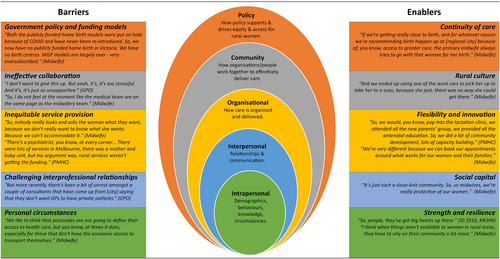

The socio-ecological model (SEM) was used following analysis to articulate the barriers and enablers health care providers perceive exist for rural women in accessing comprehensive perinatal care. The themes developed from the data demonstrated multilevel characteristics. The SEM framework has been adapted widely across health disciplines to acknowledge the complex interaction between intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy factors in determining health behaviours and outcomes.28 This was considered appropriate given the complex interplay between different dimensions of perinatal care and rurality.

2.8 Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from SHE Low Risk Human Ethics Committee, La Trobe University, and this study was conducted in compliance with the NHMRC National Statement on ethical Conduct in Human Research (2018). Participants were informed about their choice to withdraw from the study in writing at registration. At the commencement of the interviews, participants were provided with information regarding the purpose of the study, how the interview would be conducted and informed that they could stop the interview at any time.

3 RESULTS

Nine rural perinatal health care providers participated in online interviews with duration ranging between 30 and 60 min. Table 3 outlines the participant characteristics for this study. Their age groups ranged between 20–29 and 60–69 with years of clinical experience ranging from 3–5 to more than 20 years, and all participants were female. Participants provided a range of perinatal services to rural women. Rural perinatal health care providers identified several barriers and enablers they perceived exist for women in rural areas in accessing comprehensive perinatal care. Figure 1 illustrates the findings organised into the SEM framework.

| Participant no. | Profession | Modified Monash model category | No. of years providing perinatal care to rural women | Age (in years) | Type of perinatal care provided | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy care | Labour and birth care | Postnatal care (inpatient) | Postnatal care (in the home) | Early parenting support (in the home) | Early parenting support (in office/clinic) | Lactation support | Perinatal mental health care | |||||

| 1 | Registered midwife (mainstream) | 4 | 6–10 | 60–69 | √ | |||||||

| 2 | Mental health clinician | 3 | >20 | 50–59 | √ | |||||||

| 3 | Endorsed midwife (privately practicing) | 3 | >20 | 60–69 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 4 | Registered midwife (mainstream) | 5 | 11–20 | 40–49 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 5 | Registered midwife (MGP) | 4 | 6–10 | 30–39 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 6 | Registered midwife (MGP) | 5 | 3–5 | 30–39 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 7 | General practitioner obstetrician (GPO) | 4 | 11–20 | 50–59 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 8 | Registered midwife (mainstream) | 3 | 3–5 | 20–29 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 9 | Maternal and child health nurse (MCHN) and midwife | 5 | >20 | 50–59 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

- Abbreviation: MGP, Midwifery Group Practice.

3.1 Barriers

3.1.1 Intrapersonal-level factors

We like to think that postcodes are not going to define their access to health care, but you know, at times it does, especially for those that don't have the economic access to transport themselves. (ID 6, Midwife, 30–39, MMM5)

We have a lot of women that don't access care, because their partners don't want them to… we do have a high rate of domestic violence in [rural town]. So, people can then have less access. (ID 8, Midwife, 20–29, MMM3)

You can't ask for a choice that you don't know exists. (ID 3, Midwife, 60–69, MMM3)

Everyone knows what nurses do, and what doctors do, but people don't really understand what midwives do and not even to the full extent of what we do, I think. (ID 5, Midwife, 30–39, MMM4)

3.1.2 Interpersonal-level factors

I don't want to give this up. But yeah, it's, it's too stressful. And it's, it's just so unsupportive. (ID 7, GPO, 50–59, MMM4)

So, a woman goes along to her GP obstetrician and says, I want to see a private midwife. Can you give me a referral? The answer is outstandingly usually no. (ID 3, Midwife, 60–69, MMM3)

A lot of it was about control by the unit manager – she had a reputation of doing you in if you were a fairly senior midwife. (ID 1, Midwife, 60–69, MMM4)

3.1.3 Organisational-level factors

Perinatal mental health care access is incredibly difficult. There are not enough local perinatal mental health specialists full stop. The wait to get into them is huge. (ID 7, GPO, 50–59, MMM4)

Overall, participants reported a severe shortage of GPs providing services in rural towns—particularly those with expertise or interest in maternal and infant health.

The women have no choice but to access their birthing hospital's service with unknown care providers. (ID 4, Midwife, 40–49, MMM5)

Further to this, participants reported that some rural areas in the state do not have domiciliary midwifery services for new mothers. This can be particularly challenging for Maternal and Child Health Nurses (MCHNs) who struggle to bridge this gap in the context of high activity, large distances and inadequate workforce.

So therefore, even if the woman pays the privately practicing midwife to attend her, she can only come in as a support person. So, this whole incredible concept that we know is research evidence-based – about continuity of care being gold standard maternity care – we can't access that here. (ID 4, Midwife, 40–49, MMM5)

3.1.4 Community-level factors

Some of them are actually getting, like, discharged after 12 h or 24 h, they haven't even had all their hospital tests…but we don't have the, you know, equipment or labs or transport options to be doing things like that. (ID 9, MCHN, 50–59, MMM5)

3.1.5 Policy-level factors

So, what happens for women is that they pay a fee for every antenatal appointment… So, it's not… they can't just go and get pregnancy care for free. (ID 5, Midwife, 30–39, MMM4)

150 bucks out of pocket even with a mental health care plan… And then in the beginning, she might need to see someone every week, every fortnight. And yeah, people just aren't in a position to afford it. (ID 7, GPO, 50–59, MMM4)

In addition, participants indicated that the funding overall for perinatal services is inadequate with clinicians' experiencing high workloads, inadequate time to provide quality care and inefficient, outdated infrastructure. A lack of commitment and advancement in digital health solutions further contributes to fragmented perinatal care systems, according to participants.

3.2 Enablers

The participants universally noted the strengths of the communities and health services in which they work, despite the inherent challenges they face.

3.2.1 Intrapersonal-level factors

I think when things aren't available to women in rural areas, they have to rely on their community a lot more. (ID 1, Midwife, 60–69, MMM4)

3.2.2 Interpersonal-level factors

We are from a rural background, we understand the difficulties, we understand the socioeconomic struggles. We understand housing issues… We know the women's stories. We know the women's families. (ID 6, Midwife, 30–39, MMM5)

3.2.3 Organisational-level factors

We like to remove any obstacle for women accessing the service, so women can self-refer. (ID 2, Perinatal Mental Health Clinician, 50–59, MMM3)

3.2.4 Community-level factors

Look, you can't really put into words what that sort of satisfaction and feeling is. That's what…that's what draws people to rural…draws doctors to rural general practice – continuity and knowing people and knowing your community. (ID 7, GPO, 50–59, MMM4)

3.2.5 Policy-level factors

Midwives go into private practice for their own reasons… it's because you believe in the model of care. And you want to be able to offer that, which is why I went into it, I wanted to be able to do continuity care. And there was no other way to do that, in [rural town]. (ID 3, Midwife, 60–69, MMM3)

4 DISCUSSION

Perinatal health care providers who participated in this study identified multi-level, complex barriers that exist for rural women in accessing perinatal care in their own communities. The impact of the rural determinants of health on rural women's capacity to access and remain engaged with perinatal care was highlighted in this study. These findings align with a recent Australian study examining barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health care for rural women, which found that access to services was affected by women's knowledge and awareness of services, the cost of health care, distance, insufficient staff to deliver care, limited service availability and a lack of woman-centred approaches to care.29 Further to this, a recent systematic review examining barriers and facilitators of maternal health care utilisation in the perinatal period for women experiencing social disadvantage found that relationships with caregivers was both a barrier and a facilitator with women choosing to disengage from care if their caregiver was unapproachable, unavailable or culturally insensitive.30 This review also found that costs (both direct and indirect) associated with perinatal care and a lack of co-ordination and continuity also created barriers to accessing care.30 These findings align with those of this study.

Consistent with our findings, internationally, in other high-income nations, similar barriers of a multidimensional nature have been reported by health care providers. Poor communication between health care providers, time and workforce constraints on the rural health workforce and fragmented care systems create barriers to accessing health care in rural areas.31 Persistent workforce shortages, clinician burnout and the cost of care have also been acknowledged by rural health care providers as contributing to inequity in access and outcomes for rural people.32

Rural perinatal health care providers who participated in this study also identified several key enablers that they believe facilitate access to perinatal care for rural women. The positive impact of community and social capital in rural areas was acknowledged as a supportive mechanism for women generally and also beneficial in the development of therapeutic relationships. Social capital refers to the resources (both tangible and intangible) that individuals and groups can access by virtue of their social networks.33 The beneficial impact of social capital on health outcomes has been acknowledged broadly in the international literature33-35 and more specifically in the rural context in relation to a sense of community and neighbourhood cohesion.36

In this study, rural perinatal health solutions such as continuity of care models and digital health practices were recognised as enablers to rural women accessing perinatal care by participants in this study. Midwifery continuity of care models (midwifery group practice), which are supported by strong evidence of effectiveness37 are available to only 10.1% of women in Victoria14 with access for rural women being further restricted. This study found, however, that when these models are available in rural areas health care providers believe this enhances access to care. ‘Virtual’ or technology enabled consultations have been shown to be effective modes of providing care to pregnant women particularly in rural or remote contexts,38 demonstrating improved engagement with recommended perinatal care schedules without changes in perinatal outcomes.39

4.1 Implications for policy and practice

This study has identified a number of addressable factors that, if addressed, could improve access to perinatal care for rural women. Modifiable factors include education for women and families regarding health systems, models of care and their rights as consumers of maternity care, equitable distribution of perinatal services, improved interprofessional relationships enabling collaborative approaches to care and equity-based funding models for perinatal services regardless of geographical location.

In Australia, Woman-centred care: Strategic directions for Australian maternity services, recognises access as one of four core values in the provision of woman-centred care.13 A key principle of improving access to maternity care is ensuring women have access to appropriate maternity care where they choose, from conception until 12 months after birth, with the rationale for this principle cited as ‘women want to be able to access maternity care in their geographic location’.13 A recent evaluation of the implementation of the strategy, however, found that it remains largely aspirational and is yet to be operationalised, particularly with respect to access to woman-centred care.40 Our study highlights the importance of strengthening the commitment to achieving this strategy for rural and remote women and their families.

Optimising the rural perinatal workforce, thereby ensuring choice for rural women, will create sustainable models of care that do not disintegrate the integrity of the care provided. This study has demonstrated that rural communities experience severe shortages of GPs (particularly GPs with procedural skills and expertise in maternal and infant health), midwives, maternal and child health nurses and perinatal mental health care specialists. In the nursing profession, rural health care deficits are often addressed through advanced practice roles—for example, rural and isolated practice registered nurses (RIPRN) and nurse practitioner roles.41 For midwives, a similar registration and practice pathway exists but is yet to be fully implemented in rural Victoria largely due to a lack of acceptance by health services and obstetric colleagues.42 Functional and effective collaborative relationships between rural health services and endorsed midwives could enable expansion of the rural perinatal workforce and enhance care options for rural women (including continuity models).43

Examples of flexible and innovative perinatal care models were identified as enablers and celebrated by participants in this study and were used to illustrate how barriers could be removed for rural women. For example, rural midwifery continuity of care models were identified as an enabler by participants,37 and yet14 access to these models for rural women is profoundly restricted. Collaborative funding models (state and federal) that support the development and implementation of woman centred models of care in rural and remote regions at no cost to women may induce sustained engagement with care and better perinatal outcomes.

4.2 Strengths & limitations

Strengths of this study include recruitment of a range of professionals groups, including a GP obstetrician and midwives from private, mainstream and MGP models across the state, and data saturation was achieved. Participants worked in a range of rural communities spanning Modified Monash Models 3–5 (large-to-small rural towns), which ensured the small but important differences in the context of their experiences were captured.

The sample size of this study was comprised of nine rural perinatal health care providers and, as such, there may be barriers and enablers perceived by rural perinatal health care providers that have not been acknowledged or explored in this work. A recent systematic review found that between 9 and 17 interviews, particularly in homogenous study populations and narrowly defined objectives, are adequate for saturation in qualitative research.44 Importantly, in this study, analysis of the last three sequential transcripts did not develop any new codes or themes indicating data saturation.

The data presented here represent the perspectives of rural perinatal health care providers, informed by the experience of providing care to, and the interactions with, rural women, and the authors acknowledge these views may not align with the perspectives of rural women.

4.3 Recommendations for further research

This study has not sought to illuminate the inequitable impact experienced by First Nations women living in rural and remote Victoria; however, First Nations women are disproportionately affected by the disparities that exist in rural perinatal care provision with 32% of First Nations people living in remote or very remote areas.2 Evaluating health care providers' perspectives of barriers and enablers that exist for First Nations women (in addition to women's perspectives) in accessing perinatal care would be beneficial in developing a deeper understanding of the perinatal landscape in rural areas. Similarly, the barriers faced by refugee and culturally and linguistically diverse women living in rural communities need to be evaluated acknowledging that challenges relating to language and culture may create additional barriers to accessing perinatal care45 that have not been addressed by this study.

5 CONCLUSION

This study has highlighted the perceived barriers that rural women face in accessing perinatal care schedules from the perspective of rural perinatal health care providers. The impact of social determinants of health is significant and the inequitable distribution of disadvantage in rural communities amplifies the effect. In addition, health care providers perceive that rural women face barriers that are created or sustained by complex interpersonal, organisational, community and policy factors that are intrinsic to rural health care delivery. The persistent and inequitable barriers that exist for rural women, coupled with poorer perinatal outcomes, should be viewed as the burning platform that indicates an urgent need to change the way we finance, structure and deliver perinatal care in rural communities with consideration given to all socioecological factors that hinder or enable effective care access. The strength and importance of rural culture has also been highlighted in this study and contributes to the well-being of rural women despite challenging circumstances.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Fiona Faulks: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – original draft; methodology; validation; writing – review and editing; formal analysis; data curation; visualization; project administration; software. Kristina Edvardsson: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing; supervision; validation. Touran Shafiei: Conceptualization; validation; methodology; writing – review and editing; supervision.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FF is a PhD student and is the recipient of a stipend scholarship from La Trobe University and has been awarded the Betty Jeffrey Award by the Australian Nurses Memorial Centre to support completion of this PhD project. Open access publishing facilitated by La Trobe University, as part of the Wiley - La Trobe University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest to declare.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Committee: SHE Low Risk Human Ethics Committee, La Trobe University. Date of approval: 19/09/2022. HEC number: HEC22233.