Who cares about Aboriginal Aged Care? Evidence of home care support needs and use in rural South Australia

Abstract

Objective

To assess awareness, needs and use of Australian Government-funded home aged care services among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples from rural and remote South Australia.

Design

Mixed-method study.

Setting

Four rural and remote communities with a higher proportion of Aboriginal populations (Ceduna, Port Augusta, Port Lincoln and Whyalla).

Participants

Fifty Aboriginal peoples aged 50–89 years (68% females) interviewed between August 2020 and October 2021.

Main Outcome Measures

Participant awareness, needs and unmet needs.

Results

88% of the participants indicated they needed home care support with daily activities (median number of needs = 3; interquartile range 2–6 needs), especially housework (86%) and transportation (59%). However, only 41% of those reporting current needs were receiving home care services. The most prevalent unmet needs were allied health (87%), housework (79%), help with meals/meals preparation (76%), shopping (73%) and personal care (73%). Overall, 62% of the participants were unaware of the Commonwealth Home Support Programme, and 54% were unaware of the Home Care Packages program. Qualitative data showed participants felt there is insufficient information and public consultation about these services for older Aboriginal adults. Regular communication in group activities was the preferable approach to becoming aware of these services rather than websites, posted materials or phone calls.

Conclusion

Further work is needed to increase home aged care service access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples living in rural and remote settings. Promotion of these programmes through local group activities could facilitate access to these services and facilitate community engagement in decision-making.

What is already known on this subject?

- Significant reforms to home aged care were introduced in February 2017 to give consumers more choices in selecting home aged care providers and services.

- Little is known about how older Aboriginal adults access and exercise their entitlements to aged care services through the Department of Health in rural and remote settings.

What this paper adds

- This paper exposes the unique challenges faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples living in rural and remote communities of South Australia in accessing and receiving home aged care services.

- Nine out of ten older Aboriginal adults declared home care support needs with daily activities, but less than half of them were accessing these services.

- Better promotion of available services and accessibility during regular group activities might lead to more awareness and use of these services based on the client's needs.

1 INTRODUCTION

Aged care is the support provided to older people to attend to their physical, medical, psychological, cultural and social needs. It is centred on the individual, responding to their capacities, abilities and requirements. Most aged care is informal, provided by families, friends, communities and volunteers.1 In Australia, the delivery of aged care services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is embedded in the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Aged Care Program Quality Standards.2, 3

With a demographic shift towards older Australians and an ageing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, these services are experiencing increased pressure to meet the needs of this growing section of the community.4 Moreover, the earlier onset of a range of chronic diseases faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations presents considerable challenges in providing culturally appropriate services and policies.5-7 According to a 2016–17 Auditor-General report, fewer than one per cent of residential aged care places are taken up by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Peoples.8 Nonetheless, they access home aged care services at rates consistent with their share of the aged care population.2, 9

There are two Australian Government-funded aged care programs providing in-home support. The Commonwealth Home Support Programme (CHSP)4, 10 is intended to provide entry-level services focused on supporting older people to maintain their health, independence and safety at home and in the community by offering home support services. These services can include home maintenance and cleaning, meals and transport services.1, 8, 11 The Home Care Packages (HCP) is another government-funded program that offers many of the same support services available under the CHSP, but they may be provided as a more structured and comprehensive bundle of services. HCP services are delivered on a ‘consumer-directed care’ (CDC) basis, which means that people can choose the provider of these services and change providers over time. There are four HCP levels of assistance, extending from basic care to high care needs.10, 12-14

Evidence from the literature shows Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations represent a ‘special needs group’ for these home aged care services.13, 15 In 2017, this was recognised within Australian Government-aged care policy by defining 50 years as the age for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples to start receiving these services. The aged care reforms introduced in 2017 also aimed to give consumers more choices in selecting a home aged care provider to make the aged care system more client-driven, market-based and streamlined.8 However, there are unique challenges faced by rural and remote communities, especially Aboriginal people, when they try to access and receive aged care services. To address these challenges, these programs should focus on appropriate engagement and developing culturally appropriate approaches to aged care.3, 16, 17

Finding a culturally safe service can be difficult in regional and rural areas.2, 16 Additionally, the lack of choice concerning health and aged care services is particularly evident for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.2 For example, few providers specialise in providing culturally appropriate and flexible models of care targeted at older Aboriginal and Torres Islander Peoples.4, 16, 17 At present, these services are largely delivered by local non-government organisations (i.e. religious, community-based, charitable), which are more likely to implement the required adjustments to their operations and outlook.18

Given that most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples need to access aged care services through the CHSP, HCP or residential care programs, it is imperative that the Department of Health can provide continuity of services with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations focus, especially in rural and remote regions. However, there is evidence that those with limited access to technology cannot access aged care services as they should.1 In addition, the failure to properly value and engage with older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations and families has resulted in unequal access to home aged care services.18 Therefore, there is a need to improve the targeting, access and delivery of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-focused services and to monitor the ongoing impacts of aged care policies and programs upon Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.4, 11, 16, 17

This original research aimed to explore the home aged care service needs and the current use of CHSP and HCP services among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples living in rural and remote South Australia (SA).

2 METHODS

This is a mixed-method study combining quantitative and qualitative data collection using yarning-based methodologies. One of the critical strengths of yarning-based methodologies is that the project design configures the researcher's power relations; utilising Aboriginal storytelling or yarning provides a deeper understanding, complementing a two-way research paradigm for collaborative research.19-21 The first author, a Nukunu Aboriginal person based in Port Augusta, led the study team. Author 1. also acted as an Aboriginal Engagement Coordinator to ensure that ‘spirit and integrity’ were at the forefront of all community and stakeholder engagement activities.

2.1 Sample and recruitment

A purposive sampling method was used to achieve a total sample of 50 older Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Peoples across four rural locations in the Eyre Peninsula (SA): Ceduna, Port Augusta, Port Lincoln and Whyalla.22 These locations were selected to obtain a broader perspective on current needs, use and preferences related to aged care services in areas with different socioeconomic profiles, service availability, population size and remoteness classification.22

Since 2017, aged care eligibility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples has been extended to those aged 50 years or older, compared with 65 years or older for non-Indigenous Australians.1, 7, 23 Therefore, participants were included if they were Aboriginal people aged 50 years or older with a residential address in one of the four locations, independent of whether they were currently receiving home care services. The recruitment process aimed to include 5–10 Aboriginal participants aged 50 years or older from each of the four rural locations. Participants were excluded if they were aged <50 years, unable to communicate directly or through family or other relatives, or had any neurological condition that affected their capacity to understand the project objectives.

The initial step involved consulting with local Aboriginal community representatives, Aboriginal workers from different organisations and non-Aboriginal people representing service providers. Those groups provided insightful and preliminary information about the current lack of culturally appropriate services and perceived barriers to aged care service delivery. They also acted as brokers for participant recruitment.

Finally, face-to-face meetings with community representatives and potential participants were conducted to explain the significance of the study and its potential benefits to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Aboriginal Community-Controlled services supported word-of-mouth recruitment and assisted in subduing distrust with the intent of the research. In addition, these services shared the invitation flyers seeking volunteers to participate in the study.

The original proposal was designed to complete the interviews between March and August 2020. However, due to restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic to organise acceptable and safe face-to-face meetings with the Aboriginal community, the interviews and Yarning sessions occurred between August 2020 and October 2021.

2.2 Data collection

Pilot group questionnaires were trialled in two locations (Port Augusta and Port Lincoln), including Aboriginal participants not included in the final sample. After revising the original material, a semi-structured group interview process (yarning circles) was implemented to suit participants from the four locations.19-21 The final instrument included multiple-choice questions, Likert scale rating (quantitative) and open-ended questions (qualitative) to encourage people to speak about and engage with different aspects of their care (see Appendix S1).

The lead Aboriginal researcher Author 1, worked with the participants through group interviews. Participants nominated their preferred local cultural brokers for the group interviews. Each session was organised to last between 45 and 60 min. Transportation services to and from the meeting venue were offered to all participants, as well as financial reimbursement for their time and contribution to the study. Recommended protocols were also followed to reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection.

Based on the pilot study, reading, writing and comprehension were expected to be an issue for some participants. For these participants, their cultural broker or other elected participant transcribed their answers and any verbal comments into the written survey. In addition, any verbal participant comments not directly related to the survey questions were recorded as qualitative contributing field notes.

2.3 Data analysis

Participants' data were manually entered into a database using SurveyMonkey®, exported as a Microsoft Excel® document and then analysed in Stata MP version 15 (StataCorp). Descriptive statistics were applied to report data from multiple-choice answers and Likert scale questions. Results were presented in tables or figures displaying percentages. Comparisons between participants aged 50–69 years or 70+ years were performed using chi-squared tests (χ2) or Kruskal–Wallis test, depending on the nature of the outcome. These comparisons were made considering the different needs these age groups may face due to a higher prevalence of chronic health conditions in older ages.1, 5, 8, 11, 23

Qualitative information was analysed for commonalities between sites and common themes across groups. Qualitative data (from open-ended questions and notes obtained during the group sessions and discussions) were extracted from the Microsoft Excel® document and field notes and then analysed by the qualitative researcher Author 2 to identify the common themes. All team members had the opportunity to discuss these themes, considering the objectives of the study, the local context and literature findings. All researchers agreed on the findings.

2.4 Ethics

We established community advisory groups in each location and respected the community decisions regarding how the research would be conducted from project conception to conclusion. This enabled us to address existing or emerging needs articulated by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and communities.24 Ethics clearance was sought and granted by the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee of South Australia on 04-08-2018 (Protocol No. 04-18-780, approved on 20-09-2018). All participants received an information sheet and signed a consent form before the interviews.

3 RESULTS

The final sample included 50 Aboriginal participants (Port Augusta = 22, Whyalla = 11, Ceduna = 9, Port Lincoln = 8; see Table 1). Most participants were females (68%) or aged between 60–70 years (74%). One participant received disability benefits, and all lived at home or in assisted facilities. Table 1 also shows that 54% of the sample disagreed with the statement that they knew what kind of aged care services were available.

| Participant characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Place of residence | |

| Port Augusta | 22 (44%) |

| Whyalla | 11 (22%) |

| Port Lincoln | 8 (16%) |

| Ceduna | 9 (18%) |

| Females | 34 (68%) |

| Age distribution | |

| 50–59 years | 10 (20%) |

| 60–69 years | 19 (38%) |

| 70–79 years | 18 (36%) |

| 80–89 years | 2 (4%) |

| Not reported | 1 (2%) |

| Knows what kind of aged care services are available to them | |

| Disagree | 27 (54%) |

| Neutral | 7 (14%) |

| Agree | 16 (32%) |

| Awareness of the Commonwealth Home Support Programme | |

| Unaware | 31 (62%) |

| Aware, but not using | 15 (30%) |

| Aware and using | 4 (8%) |

| Awareness of the Home Care Packages Program | |

| Unaware | 27 (54%) |

| Aware, but not using | 10 (20%) |

| Aware, using Level 1 | 7 (14%) |

| Aware, using Level 2 | 4 (8%) |

| Aware, using Level 3 | 2 (4%) |

When asked about their awareness and use of aged care services, only 8% of the participants used CHSP services and 26% HCP services. The proportion of participants who were aware of the age care services available to them was lower among those aged 50–69 years (20.7%) than those aged 70–89 years (50.0%; χ2 [1] = 4.62, p-value = 0.032).

Participant #18: “I am not happy with the information provided by the services about Aged Care packages, the amount individuals are entitled to use and what options are available.”

Participant #5: “More awareness. More promotion.”

Participant #2: “We need someone to explain, to give more information, I think. Follow up sessions.”

Participant #43: “To have meetings to keep us up to date on services available and any changes that may occur.”

3.1 Service needs, services received and unmet needs.

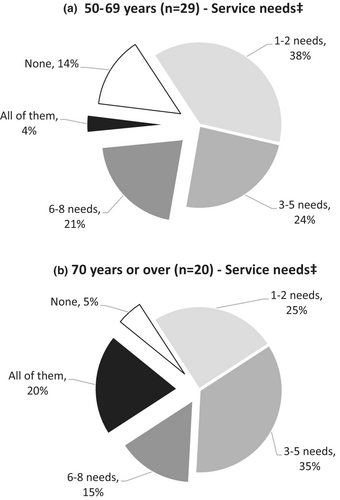

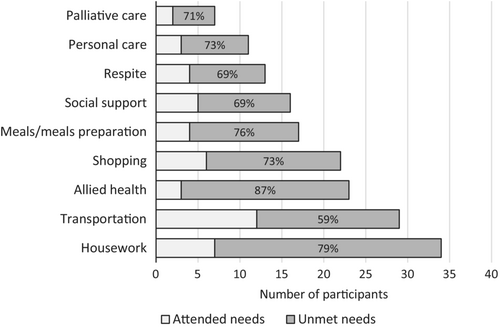

Eighty-eight per cent (n = 44) of all participants reported they had current needs requiring home care support. This proportion was similar among those aged 50–69 or 70–89 years (χ2 [1] = 0.99, p-value = 0.318). The most frequent home care support needed was housework (86%), followed by transportation (59%), allied health (46%), shopping (44%), meals or meals preparation (34%), social support (32%), respite (26%), personal care (22%) and palliative care (14%). The median number of home care service needs was three (interquartile range 2–6 needs), and 10% required assistance with all nine investigated activities. Figure 1 shows older participants were more likely to report they required support with all investigated services (20%) than those aged 50–69 years (4%), but the p-value was borderline (Kruskal–Wallis test = 2.90 [1], p-value = 0.09).

Participant #43: “How long do you need to wait? Where are our services?”

Participant #46: “Where are my/our services in my town?”

Participant # 47: “Does anyone care about our services in town?”

Combining the reported home care service needs with the current use of these services enabled us to explore the burden of unmet needs among the participants. Figure 2 shows that between 59% and 87% of participants had unmet home care service needs. The most prevalent unmet need was allied health (87%), followed by housework (79%), meals/meals preparation (76%), shopping (73%) and personal care (73%). This was also evident in some participants' open-ended responses.

Participant #42: “Not enough services, need more support. Help in everything. More health services.”

Participant #21: “We need more trained Aboriginal people workers in aged care programs.”

Participant #22: “We need more trained Aboriginal people in aged care to explain to us.”

Participant #40: “the ACAT (Aged Care Assessment Team) assessor is driving from Port Lincoln every 6 months and is not Aboriginal.”

Participant #29: “I have constant contact with health workers; not everything is understandable.”

Participant #12: “No services during Covid-19: services slowed right down.”

Participant #17: “They are restricted by policies; what they can do and cannot do in your home.”

3.2 Receiving information about aged care services.

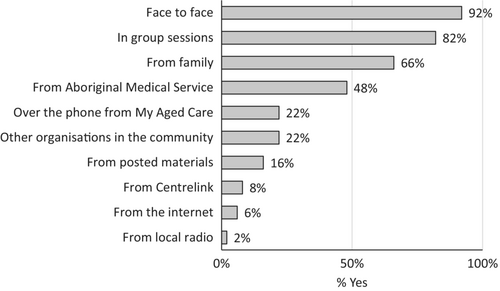

Figure 3 shows that the preferred means of receiving information about accessing aged care services reported by the 50 participants were face-to-face (92%) and group information sessions (82%).

Participant #6: “We want more information as a group. More meetings.”

Participant #18: “I am not happy with the information provided and where to get it.”

Participant #19: “…keep me connected with the other Elders, getting out of the house and talking to people”.

Participant #50: “Don't know how to use the website, as it is too complicated.”

4 DISCUSSION

The main finding of this community-engaged research is the substantial disparity between current needs and home aged care services received by older Aboriginal adults in rural SA (between 59% and 87%). Moreover, different barriers exist to accessing these services and/or receiving them in a timely manner. In the 2016 Census (before the 2017 Aged Care Reform), 27% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples aged 65 years and over reported needing assistance with core activities, self-care, mobility or communication tasks, compared with 19% among non-Aboriginal people.14 In 2021, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety acknowledged that geographical diversity presents a range of challenges for delivering all aged care services across remote and very remote Australia. This is particularly relevant to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, who comprise 16% of remote and 46% of very remote populations.14 In remote communities, with few aged care services and a lack of respite, providing these services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is challenging. The ‘one size fits all’ approach for the cities did not work in remote settings with little or no alternative care options.14, 25

All study participants were over 50 years old, and none used aged care residential facilities; they were ‘pretty proud of being independent and self-assessing their needs’. This finding is consistent with a systematic review published in 2016 by a group led by Davy and Kite.2 That study highlighted the importance of promoting independence by distinguishing between requiring some assistance instead of being treated as ill. Access to aged care services in Australia is determined by people's needs rather than their age. The Aged Care Act 1997 designates some groups as ‘people with special needs.’ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples are one of these special needs groups.6 Based on our findings, nine out of ten participants reported current home care support needs regardless of their age. A previous study also reported that Community Aged Care Package (CACP) usage rates were much higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples aged 50–69 (12 times more likely) or 70+ years (twice more likely) than their non-Indigenous counterparts. Authors of that study remarked that the lower eligibility age for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples better matches the use of CACPs than residential care.9 This is in recognition that health conditions associated with ageing often affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples at an earlier age.6, 9

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 3400 older Indigenous Australians were using home care services in 2020. Home care is the most common aged care service type used by Indigenous people aged 50 and over, especially among women – 67% compared with 58% of men. The same report also showed that 44% of older Indigenous Australians using HCP services received level 2 care (low care needs), and 31% received level 4 care (high care needs). Level 1 care (basic care needs) was the least common level of home care being received (1.1%).6 In our study, most participants receiving HCP services reported using Level 1 services. This result is probably biased, considering we used a convenience sample and participants with less complex needs were more likely to be able to attend these sessions. Moreover, unfamiliarity with these programmes and unmet needs are additional factors that may have influenced our results: half of our sample indicated they had three or more needs, and 10% required support with all nine investigated services.

The Australian Department of Health has made information about these services available through websites (My Aged Care portal) and printed material. Nonetheless, between 54% and 62% of the participants were unaware of the available home care service programs, especially those aged 50–69 years. This result is not surprising, as more than 90% of the participants indicated the best means of receiving information about accessing aged care services was face-to-face or during informative in-group sessions, whilst less than 20% mentioned the internet or printed material. Advocating, encouraging and facilitating aged care services education would enable Aboriginal families to articulate better informed and culturally appropriate care choices for their older people to improve their quality of life and well-being in their remaining years.

Meeting the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be guided by consumer input and recommendations of independent reviews based on research evidence. Similar findings were reported by Brooke 10 years ago, suggesting there has been little progress in improving access to aged care services.15 Notably, the failure to properly value and engage with older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and families has resulted in additional challenges and inequalities in accessing aged care services, with implications for workforce planning.2, 26-28 Moreover, the collaboration between health services and aged care assessment should underpin streamlined evaluation, especially in regional and remote areas.

Better collaboration would also allow a timely and consistent response to consumer requirements, especially if these programmes involve highly skilled tertiary qualified workers from health-related disciplines with experience in aged care and assessors who meet the required competencies (e.g. Aboriginal Health Workers and Aboriginal Health Practitioners).28

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety heard that despite poorer health, higher levels of disability and early access to aged care, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples are underrepresented in the aged care system.14, 25 Moreover, recommendation 51 of the Australian Government Response to the Final Report of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety highlighted the need for workforce planning and development, including setting and refining requirements for minimum staffing levels and qualifications.29 The period for attending that and other recommendations was December 2022, representing a significant time wasted considering the previously reported issues.14, 25 Our study participants indicated they waited over 12 months for a reply on their assessments to receive HCP or CHSP. Martin Luther King Jr said “A right delayed is a right denied”. This could be alleviated if the Australian Government accepted recommendation 39: to clear the HCP waiting list, otherwise known as the National Prioritisation System.29 However, this depends on factors that vary across urban, regional, rural and remote areas, such as the availability of providers and workforce supply.30 Different leading aged care consumer organisations led by the Council on the Ageing (COTA) are advocating for faster actions by the Aged Care Royal Commission to deliver appropriate, safe and timely aged care services, especially for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples living in rural Australia.31 This includes recruiting and retaining quality staff and evolving next-generation service models that facilitate viability. Sadly, the sheer volume of reviews in the aged care sector is itself indicative of profound and entrenched systematic flaws. After so many reviews, the problems still exist.1, 14, 25

To ensure that aged care services are safe and culturally appropriate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander older people, the Australian Government is now working in partnership with the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Ageing and Aged Care Council Limited (NATSIAACC), and the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People.32 A start is encouraging, but it is the finish that counts.

4.1 Limitations

There are limitations of this study relating to the size sample and the choice of rural locations that might prevent the generalisation of the findings. However, considering the original question was initiated by the local community in Port Augusta, the Eyre Peninsula region (SA) provided a large area for investigation. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic circumstances constrained the level of engagement and the final number of participants willing to contribute. Nevertheless, the study provides unique insights into the access to aged care services by older Aboriginal people in rural and remote SA, adding to the body of other studies undertaken with aged care providers.

5 CONCLUSION

This original research study has provided insights into older Aboriginal adults' awareness, needs and use of home care services. The Department of Health needs further work to maintain the service continuity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-focused aged care services in rural and remote areas. Incorporating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples' voices is essential for advancing the well-being planning for this part of the population with limited access to appropriate services, either because of their unavailability in rural and remote settings or cumbersome processes. Dissemination of information about these programs through local group activities could facilitate access to these services and promote community engagement in decision-making. Moreover, the availability of trusted, culturally safe providers is crucial. If there are no such providers, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples may not engage with mainstream services.14, 25 Exploring the providers' services in this region and engaging with families and carers will bring additional perspectives on home care services for older Aboriginal adults.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kym Thomas: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; formal analysis; project administration. Pascale Dettwiller: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; supervision; formal analysis. David Gonzalez-Chica: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; supervision; formal analysis; methodology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are thankful to the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities, individuals and organisations for participating in our research, as well as to the Australian Department of Health for supporting the Adelaide Rural Clinical School through the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program. This paper is an outcome of the research ‘Recent and Future Changes in Home Care and the Unique Challenges Associated with Service Delivery for Aboriginal People’. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Adelaide, as part of the Wiley - The University of Adelaide agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research did not receive financial support from any particular source, nor has it been published elsewhere.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

We established community advisory groups in each location and respected the community decisions regarding how the research would be conducted from project conception to conclusion. This enabled us to address existing or emerging needs articulated by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and communities. Ethics clearance was sought and granted by the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee of South Australia on 04-08-2018 (Protocol No. 04–18-780, approved on 20-09-2018). All participants received an information sheet and signed a consent form before the interviews.