Camera-trapping confirms unheralded disappearance of the leopard (Panthera pardus) from Waza National Park, Cameroon

Introduction

Africa's megafauna are currently experiencing broad, continent-wide population declines. Large carnivores in particular, including lions, African wild dogs and cheetahs, have suffered extensive range contractions and population collapses (Breuer, 2003; Ray, Hunter & Zigouris, 2005; De Iongh et al., 2009; Riggio et al., 2013; Brugiere, Chardonnet & Scholte, 2015), nowhere more severe than in West and Central Africa (Burton et al., 2011; Henschel et al., 2014; Brugiere, Chardonnet & Scholte, 2015). The recent history of large carnivore declines in northern Cameroon may best illustrate this urgent conservation context (Breuer, 2003; Bauer, 2007; Tumenta et al., 2010; De Iongh et al., 2011; Brugiere, Chardonnet & Scholte, 2015). Waza National Park (WNP), historically home to many more of the continent's large mammals, continues to suffer declines in its large carnivore guild. Waza's cheetah population disappeared some time ago (Bauer, 2003; Breuer, 2003; Brugiere, Chardonnet & Scholte, 2015) and only about 20 lions remain in the park, making it one of the most endangered lion population in West and Central Africa (De Iongh et al., 2009; Tumenta et al., 2010; Henschel et al., 2014). In addition, although it is unclear whether African Wild Dogs ever occupied the Waza-Logone floodplain (Woodroffe, Ginsberg & MacDonald, 1997), the species is now extinct in the country (De Iongh et al., 2011).

Among Africa's large carnivores, the regional status of the leopard (Panthera pardus) has received comparably less attention, but is believed to be declining (Henschel et al., 2008). Prior anecdotal interviews at Waza suggested that the leopard may also have become extirpated from the region (Bauer, 2003). Due to the cryptic, solitary nocturnal behaviour of the leopard and its possibly low population size around this time, however, there was little consensus as to when or whether indeed this happened. Our efforts here in part represent the first direct attempt to answer the lingering question: Does the leopard still occupy the WNP?

Methods

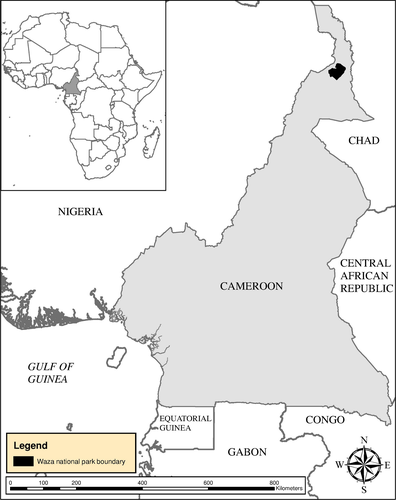

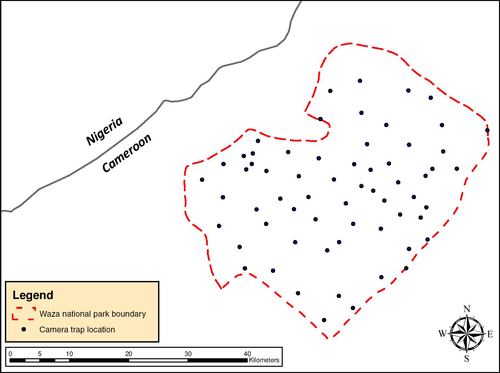

Over a 6-week period during the hot/dry season (March–April) of 2008, we conducted a rapid camera-trap assessment of Waza National Park (Fig. 1), a 1700 km2 protected area of Far North, Cameroon, with habitats considered typical of the Sundanian–Sahelian ecoregion. Twenty-one stations each consisting of a single camera-trap operated concurrently for each of three consecutive fourteen- to fifteen-day sampling sessions, yielding a total of 63 stations deployed across the protected area. Cameras were of varying designs and were deployed under default manufacturer settings. Whenever possible, we placed camera-traps in proximity to watering holes, expecting this would maximize the probability of detecting most fauna (Fig. 2). As we sought wide sampling coverage and representation, the maximum distance between any two stations was fairly high (7.55 km). To optimize camera-traps for the detection of the park's resident carnivores over this relatively short survey period, all stations were baited with the partial carcasses of ungulates (e.g. kob Kobus kob) obtained from hunting zones in the Benoue Protected Area complex in the Sudano-Guinean ecoregion of north Cameroon, south of Waza National Park. Bait was used to create two scent trails for each station approximately 150 m long before it was suspended 1.5–2.0 m in a tree opposite a camera-trap; catnip was also applied to the base of each ‘bait’ tree as a secondary attractant. After each of three sampling sessions and therefore before being rotated to survey another portion of the park, the batteries for all camera-traps were replaced.

Results and discussion

One camera-trap in each of the second and third sampling sessions was stolen, while the batteries of two other units during the second sampling session expired due to excessive false triggers. Accounting for these failures, we still logged a total of 798 camera-trap nights during our rapid survey. We recorded numerous independent photographs (one species detection/camera-trap/night) of the park's known native medium–large carnivores, including the critically endangered lion (n = 21), spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta) (n = 17), striped hyaena (Hyaena hyaena) (n = 5), jackals (Canis aureus, C. adustus; n = 109), as well as a diversity of potential leopard prey (e.g. Kob Kobus kob; Roan Antelope Hippotragus equinus; Topi Damaliscus korrigum; Red-fronted Gazelle Eudorcas rufifrons; Warthog Phacochoerus africanus; Patas Monkey Erythrocebus patas). However, we failed to record a single photograph of a leopard during any of these sampling sessions.

Leopards present elsewhere in isolated West African parks appeared to have a detection rate similar to or higher than lions. For example, during two camera-trapping surveys of different portions of Niokolo Koba National Park in Senegal, Kane (2014) achieved an independent detection rate of 0.67–1.91/100 camera-trap nights for leopards without using any kind of additional attractant (e.g. carcasses as bait, catnip). In conservatively assuming the lower of these rates for our study area, we would have expected then to record one or more leopards on at least five independent occasions based on our sampling effort. This includes at least one to two detections per different habitat and sampling session assuming the use of unbaited stations. It is worth noting that Kane's (2014) maximum detection rate of lions (2.06/100 camera-trap nights) was lower than ours (2.6/100 camera-trap nights), despite the Waza population being widely regarded as one of the most threatened in Africa (De Iongh et al., 2009; Tumenta et al., 2010; Henschel et al., 2014). This was most likely due to our use of bait to encourage repeat, independent visits to sites. In Ghana's Mole National Park, Burton et al. (2011) detected leopards at a much higher rate (2.91/100 camera-trap nights) than Kane (2014) and also did not use bait or another kind of attractant; furthermore, they failed to record a single lion on camera despite confirmation of their presence in the park. In Zimbabwe, du Preez, Loveridge & Macdonald (2014) showed that camera-trap detection rates for leopards were significantly greater when using bait as an attractant as compared to using unbaited camera-trap stations. In considering our spatial coverage of the park with camera stations; the use of game carcasses and catnip as carnivore attractants; our ability to detect the park's critically endangered lions as well as its more common resident carnivores; and the sampling effort needed to detect leopards in other isolated West African parks, we are confident we would have detected the leopard if it still occupied WNP. Moreover, since the completion of all field activities and through the preparation of this manuscript, no confirmed observations or other evidence (e.g. sign, second-hand reports) of the leopard have occurred among Waza National Park staff and officials, or local people in villages surrounding the park (P. Tumenta, unpub. data). Included among the latter group are those experiencing regular conflict with other native carnivores of the region (e.g. lions, hyaenas, jackals), but never leopards. Because Waza otherwise appears to contain less degraded and more intact Sundanian–Sahelian woodland structure than adjacent areas, this evidence in total would suggest that the leopard has indeed been extirpated from the immediate region, and not just the park.

It is probable that direct anthropogenic pressures resulting from continent-wide, habitat conversion is driving the decline of leopards on the geographical scale it is impacting lions (e.g. Bauer et al., 2015); however, it is unclear whether land management implications for both species are similar. In Waza, however, direct anthropogenic pressures may have acted in concert with a heightened competitive dynamic among lions, hyaenas and leopards to cause the latter's disappearance, possibly facilitated by a decline in local abundance and diversity of potential prey. Scholte, Adam & Serge (2007) offered evidence that the declining long-term trend in Waza's kob population and the disappearance of its waterbuck (Kobus elypsiprymmus) may have been due to the long-term interaction of low rainfall, the construction of the Maga dam and increased livestock grazing and poaching. They also refer to the probable disappearance of other ungulates, including bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus) and red-flanked duiker (Cephalophus rufilatus), which, along with waterbuck, our surveys also failed to detect. More directly, it is possible that historical patterns of conflict between local villages living in the Waza region and the park's carnivores, particularly the lion (e.g. De Iongh & Bauer, 2008; Tumenta et al., 2010), may have also involved the leopard and thus included retaliatory killings. Targeted poaching could have also played a role in why leopards disappeared from Waza National Park. There are reports of tourist markets outside of Mole National Park in Ghana for example openly selling leopard skins (Burton et al., 2011). Additional threats posed by extra-national militants and/or poachers with automatic weapons, known to enter the Park and shoot at wildlife (P. Tumenta & A. J. Giordano, unpub. data), may have also contributed to the decline of leopards and leopard prey. Ultimately, that most investigations of conflict over the past decade or more have focused on the park's lion population, the relatively higher visibility of social carnivores such as lions and hyaenas, the solitary habits of leopards and possibly a long-standing mistaken presumption that leopards were not threatened in Waza may have all contributed to its unheralded extirpation.

The leopard's ‘quiet’ disappearance from Waza National Park is indicative of a trend occurring more widely (Jacobson et al., 2016). Also, whereas the decline of other large carnivores in West and Central Africa has received considerably more attention, leopards had already disappeared from approximately 37% of their historical range in Africa a decade ago (Ray, Hunter & Zigouris, 2005). Aside from South Africa, the most pronounced decline in African leopard populations appears to be in the Sahel belt, of which northern Cameroon and neighbouring Nigeria are a part (Henschel et al., 2008). As additional leopard declines may be occurring unnoticed, we recommend more large-scale, rapid camera-trapping assessments of local populations in and around protected areas across the region. We call on investigators to pay particular attention to monitoring the status of local leopard populations and identifying immediate threats to their survival.

Acknowledgements

Research conducted here was supported in part by the Institute of Environmental Sciences (CML) at Leiden University (The Netherlands) in collaboration with the Centre for Environment and Development Studies at the University of Dschang in Cameroon. We would also like to thank Mike Shaffer for his assistance with the preparation of the maps for the figures herein.