Nectar-drinking Elephantulus edwardii as a potential pollinator of Massonia echinata, endemic to the Bokkeveld plateau in South Africa

Introduction

Pollination of flowers by nonflying mammals is a rare phenomenon conducted mostly by rodents, marsupials and primates (Carthew & Goldingay, 1997; Wester, Stanway & Pauw, 2009). Plants visited and pollinated by nonflying mammals belong to about ten different families, mainly from the Southern Hemisphere (Wester, Stanway & Pauw, 2009 and citations therein). One example is the tribe Hyacintheae (Asparagaceae family) of which three species, Massonia depressa Houtt., Whitedia bifolia (Jacq.) Baker and Eucomis regia (L.) L'Hér., were discovered to be pollinated by different species of mice in South Africa (Johnson, Pauw & Midgley, 2001; Wester, Stanway & Pauw, 2009; Wester, Johnson & Pauw, 2013). In addition, nectar-drinking elephant shrews (order Macroscelidea) were found to pollinate these species (Wester, 2010; Wester, Johnson & Pauw, 2013; Wester, 2015; P. Wester, unpubl. data). This study addresses a further representative of the Hyacintheae, Massonia echinata L.f. (species concept after Martínez-Azorín et al., 2015), endemic to the Bokkeveld plateau in South Africa. First observations of floral visitors are presented and discussed in relation to floral characters, regarding the animals' role as pollinators.

Materials and methods

Massonia echinata was studied in Oorlogskloof Nature Reserve (Driefontein 31.50410°S 19.11796°E, 670 m; near Kleinheiveldvoetpad 31.46790°S, 19.03624°E, 800 m; near Saaikloof 31.44721°S, 19.06951°E, 720 m) south of Nieuwoudtville, Northern Cape, South Africa. The plant grows in rocky habitats within Mountain Fynbos. Floral measurements were undertaken to the nearest 0.5 mm. The Saaikloof population was monitored with motion and infrared sensor camera traps (Bushnell nature view 119440, Kansas City, U.S.A.) for potential pollinators. The camera traps have 0.7-s shutter lag and were set on maximum sensitivity, 1-min video recording, 1-s interval and low IR illumination. Close-up lenses enabled 50–150 cm operating distances. One to five camera traps were running for 9 days and nights (580 h in total, 28.8.−6.9.2015), monitoring one to twelve inflorescences per camera trap (about 50 in total).

Results

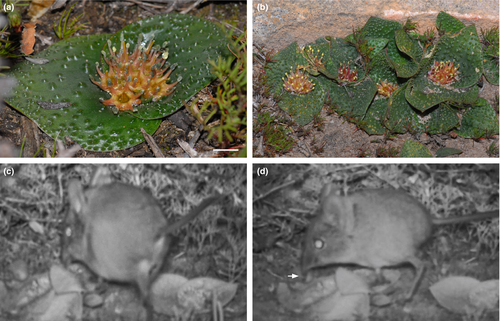

Massonia echinata has inflorescences at ground level with up to fourteen densely arranged flowers (Fig. 1a–b, Table 1). The inconspicuous flowers are similar in colour to the surrounding ground (Fig. 1b, Table 1). The radially symmetrical flowers have small, flimsy tepals, but sturdy filaments and styles. The stamens are slightly longer than the carpel (Table 1). The somewhat curved, awl-shaped filaments are fused at their base, forming a bowl, which contains easily accessible, colourless nectar (Fig. 1a, Table 1). Floral odour is buttery and somewhat rancid, sometimes similar to old oil and Parma ham.

| Floral character | Floral dimension (mm) or character description |

|---|---|

| Inflorescence height | 12.5 ± 4.9 (7.2–27.4), n = 26 |

| Inflorescence diameter | 17.8 ± 5.7 (9.2–30.7), n = 29 |

| Stamen length | 7.8 ± 0.9 (7.0–9.5), n = 9 |

| Carpel length | 7.1 ± 1.0 (6.0–9.0), n = 9 |

| Inner diameter of nectar chamber | 3.5 ± 0.7 (2.8–5.3), n = 10 |

| Nectar chamber height | 2.8 ± 0.4 (2.0–3.4), n = 10 |

| Tepal colour | Green or greenish, flushed purple or also almost completely purplish with less green, margin white-transparent |

| Filament colour | Distally whitish or rose, often flushed purple, base green or greenish, sometimes all over beige to cream |

| Pollen sac colour | Dark blue |

| Pollen colour | Yellow |

| Ovary and style colour | Greenish or green, sometimes beige to cream, often flushed purple |

Cape rock elephant shrews Elephantulus edwardii (A. Smith 1839) were observed drinking nectar from M. echinata during two different nights between 6:50 pm (shortly after dusk) and 6:30 am (around dawn). The elephant shrews repeatedly extended their tongues into the flowers (Fig. 1c, Video S1–S4). In total, the animals licked nectar from thirteen different inflorescences during six foraging bouts (continuous time of visiting one or more inflorescences). During one foraging bout, two to eight different inflorescences were visited. Foraging bouts lasted 3- > 60 s, while time spent per individual inflorescence was 1.1–13.3 s. In one video, pollen was noticed as a circle on the elephant shrew's tip of the nose (Fig. 1d, Video S4). Although pollen transfer was not visible, the position of the pollen on the nose matched the position of the pollen sacs. Flower visits were nondestructive; no pollen, flower parts or insects were eaten. Elephant shrews were seen three times only sniffing at a flower but not extending their tongues, probably due to missing nectar.

Between midnight and 5:30 am, Namaqua rock mice Micaelamys namaquensis (A. Smith 1834) were observed three times next to the Massonia plants in the videos, but showing no interest in flowers. Only once, a mouse was nosing the flowers briefly but without touching or drinking nectar. In contrast to the elephant shrews, at least once a mouse appeared to be nervous. Cockroaches and flies were moving nonspecifically all over the plants while a Smith's red rock rabbit Pronolagus rupestris (A. Smith 1834) and a Dwarf plated lizard Cordylosaurus subtesselatus (A. Smith 1844) were noticed only near the plants.

Discussion

The present study shows that E. edwardii visits several M. echinata plants for nectar. As the animal's nose's tip is level with the flower's pollen sacs and stigma and as pollen was found at the tip of the nose, pollen transfer to the nose and the stigma is very likely.

Elephantulus edwardii has been identified as pollinator of other plant species that share several floral characters with M. echinata (e.g. M. depressa and W. bifolia). These features are likely adaptations to facilitate pollination by nonflying mammals (Wester, Stanway & Pauw, 2009 and citations therein). Whereas floral scent plays an important role in attracting crepuscular and nocturnal animals (Johnson et al., 2011; Wester, Johnson & Pauw, 2013; P. Wester unpubl. data; e.g. the predominantly nocturnal E. edwardii, Skinner & Chimimba, 2005), visual inconspicuousness excludes or does not attract other animals such as bees and birds. Bowl-shaped flowers with easily accessible nectar and protruding reproductive organs promote pollen transfer onto the mammal's snout and the flower's stigma (Wester, Stanway & Pauw, 2009). Robustness of the flowers' reproductive organs prevents damage by nectar-foraging small mammals.

There was no indication of interest in M. echinata nectar by M. namaquensis. However, it cannot be ruled out that this species or other rodents are flower visitors and pollinators of M. echinata, referring to nectar accessibility to mice and the similarly structured plant species, pollinated by M. namaquensis and other mice (Wester, Stanway & Pauw, 2009 and citations therein). Reasons for the lack of interest in nectar might be disturbance due to camera traps, or lack of nectar after elephant shrew flower visits. Overall, to evaluate the influence of mice and elephant shrews on the pollination of M. echinata in detail, further investigations should include long-term observations and proof of pollen transfer to the animals and to the stigma.

Massonia echinata and several other plants adapted to nonflying mammals (elephant shrews and mice) for pollination are dependent on their pollinators (Wester, Stanway & Pauw, 2009). Contrary, the animals as ecological generalists have access to a wider range of other resources (Skinner & Chimimba, 2005; Rathbun, 2009). Consequently, the animals are not dependent on the spatially and temporally restricted floral nectar, and thus, adaptations for flower feeding are unlikely.

Acknowledgements

We thank Johannes Afrika for locality information, Mandy Schumann for logistic support and permission to work in Oorlogskloof NR, Northern Cape Department of Environment and Nature Conservation for permits (FLORA 023/2/2015 and 024/2/2015), the Heinrich-Heine-University (Düsseldorf, Germany) for supporting L.F. (SCMG), the Schimper-Stiftung (Hohenheim, Germany), the Anton-Betz-Stiftung der Rheinischen Post (Düsseldorf, Germany) and Idea Wild (Fort Collins, U.S.A.) for supporting P.W.