Hyperepilithics—An overlooked life form of vascular plants on tropical vertical rock walls

Abstract

Vascular epiphytes are a characteristic life form in many tropical regions and often occur growing on bare rocks. South America has the highest diversity. Here, we describe a neglected life form: hyperepilithics adapted and restricted to growing on vertical (inclination above 70°) and bare rock walls without having roots intruding the substrate. Hyperepilithics are in particular present on Brazilian inselbergs and dominated by highly specialized Bromeliaceae, mainly of the genera Stigmatodon, Tillandsia and Alcantarea, whereas Orchidaceae surprisingly has a low representation. An overview of this habitat, the life form hyperepilithics and a comparison with similar paleotropical habitats (mainly inselbergs in Western/Eastern Africa and India) are provided. Attention is drawn to hyperepilithics as a most promising and not yet exploited source for a sustainable urban ‘vertical gardening’, for example in tropical megacities.

INTRODUCTION

Vascular epiphytes grow on trunks and branches of other plants without parasitizing them and are even often highly specialist to particular host plants (Zotz, 2013). Epilithic plants grow on rock surface and are usually treated under the term ‘epiphyte’ without being epiphytic (Porembski, 2007). Tree bark and rocks have a limited availability and storage capability of water (Porembski, 2007; Zotz, 2013), requiring similar adaptations to overcome to similar stresses (Givnish et al., 2007). Bromeliaceae, Orchidaceae and ferns have many lithophyte taxa and show high diversity in Neotropical ecosystems (de Paula et al., 2020; Zotz, 2013). This suggests that most current epiphytes may have evolved from lithophytes or terrestrial predecessors – or vice versa (Zotz, 2013).

On tropical inselbergs, not vertical bare rock surfaces are colonized by epilithic vascular plants often forming mats. Only few studies have addressed the diversity and ecology of mat communities (e.g. de Paula et al., 2016), however, without taking into account the plants of vertical rock walls. Thus, we present an overview of this overlooked habitat and the life form hyperepilithics and provide a comparison with similar paleotropical habitats. We expect hyperepilithics to provide a promising source for a sustainable urban ‘vertical gardening’ in tropical megacities.

VERTICAL ROCK WALLS: A NEGLECTED HABITAT FOR VASCULAR PLANTS

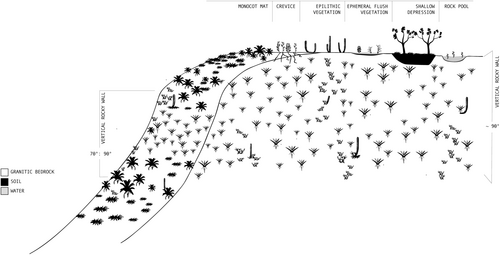

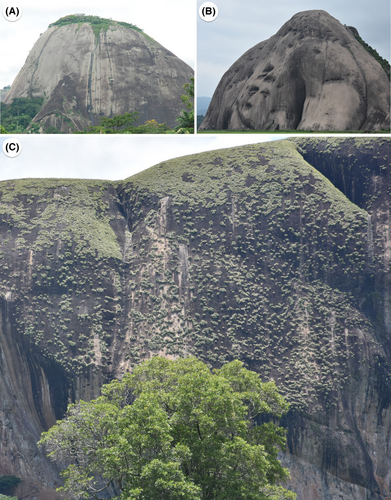

Vertical or almost vertical rock walls (VRWs) form a distinct habitat type in inselbergs with an inclination between 70 and 90° (see Figure 1). They represent important elements of inselbergs, as they can reach a height of several hundred meters. The access to them is very difficult and that imposes great physical challenges for scientists. In the Neotropics, VRWs are especially common on Brazilian inselbergs in the semi-arid Caatinga (north-eastern region) and in the Atlantic Forest (south-eastern region). The Atlantic Forest VRWs are mainly present on lowland, dome-shaped outcrops also known as sugarloaves sensu de Paula et al. (2016, 2020). For instance, VRWs are present in the iconic Sugarloaf Mountain in Rio de Janeiro, south-eastern Brazil (Figure 2). They are also present on the inselbergs in the Amazon Forest (e.g. Villa et al., 2018) and in Colombia (e.g. Aristizábal-Botero et al., 2020), but we have little information about the VRW flora in these regions. VRWs can also occur in karst formations in the Paleotropics (e.g. karsts of East Asia, Wang et al., 2019) and Neotropics (e.g. Brazilian karst, Bystriakova et al., 2019), as well as in Neotropical quartzite and sandstone rock outcrops (e.g. Tepuis from Guiana Shield, Riina et al., 2019).

HYPEREPILITHICS: DEFINITION AND CHARACTERIZATION

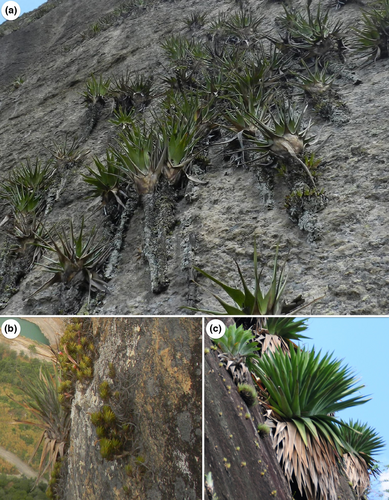

We propose the new term ‘hyperepilithics’ for vascular plants that grow on vertical or almost vertical (inclination over 70°) rock walls (Figure 3). Although VRWs are extensively covered by lichens and cyanobacteria (Porembski, 2007), only relatively few vascular plants grow exclusively on this habitat (hyperepilithic specialist), and they never appear on more gentle slopes. On the contrary, some species are not restricted to VRWs, but are commonly found on slopes with 70–90° inclination, which we call facultative hyperepilithic. A notable example of a facultative hyperepilithic bromeliad is Encholirium horridum (subfamily Pitcairnioideae), that occur in the Atlantic Forest inselbergs (de Paula et al., 2016). Other examples of facultative hyperepilithic species are some orchids (e.g. Brassavola tuberculata, Cattleya lobata and Pseudolaelia dutrae), cacti (e.g. Rhipsalis cereoides and Coleocephalocereus fluminensis) and lycophytes (e.g. Selaginella convoluta and S. sellowii). Finally, we highlight that many species can accidentally occur on VRWs, as they preferentially grow on flat to somewhat inclined (<40°) slopes, represented by example of Araceae, Cactaceae and Orchidaceae.

NEOTROPICAL HYPEREPILITHICS: TAXONOMIC GROUPS AND ADAPTATIONS

The centre of diversity for hyperepilithics lies undoubtedly in South America in the inselbergs of south-eastern Brazil, a hotspot of lithophytes plants (de Paula et al., 2020). In this region, hyperepilithic bromeliads stand out, especially the genera belonging to the subfamily Tillandsioideae. Within the hyperepilithic specialist members, the most remarkable example is Stigmatodon, with most species being restricted to VRWs (Couto et al., 2022). Equally important are species of Tillandsia subgenus Anoplophytum (e.g. T. araujei, T. castelensis and T. grazielae), which generally occur in sympatry with Stigmatodon species (see Figure 3b) on large VRWs of lowland inselbergs. Furthermore, some species in the genera Alcantarea (e.g. A. acuminatifolia, A. cerosa and A. robertokautskyi) and Vriesea (e.g. V. saundersii and V. botafogensis) are also examples of hyperepilithic specialists. Of these genera, Stigmatodon and Alcantarea are almost exclusively epilithic (but see exceptions in Couto et al., 2022), while Vriesea and Tillandsia are highly important in epiphytic communities in Neotropical Rainforests (Zotz, 2013). On the contrary, Orchidaceae genera, such as Bulbophyllum, Cattleya and Epidendrum (similarly important as lithophytes and epiphytes), preferentially grow on flat to somewhat inclined slopes in inselbergs, and are not notable in VRWs.

All hyperepilithic species possess relevant adaptations for survival on VRWs. They are able to secure themselves firmly to the bare rock so as to persist for long time spans and to survive long periods of drought. However, there appear to be no specific morphological traits that are unique to hyperepilithics, many adaptations are similar to epiphytic plants, for example CAM, succulence, presence of a velamen radicum and clonal reproduction (Zotz, 2013). Mainly in Stigmatodon and Tillandsia, we note that they: (i) are small or medium in size (ca. 5–110 cm tall when flowering; Couto et al., 2022; Tardivo, 2002) and display water-impounding tanks or non-impounding; and (ii) have xeromorphic leaves that are densely lepidote on both surfaces, which in many cases, are completely covered with a dense layer of cinereous trichomes, giving the leaf blade a silvery colour. On the contrary, larger hyperepilithic bromeliads (ca. 200–370 cm tall when flowering; Versieux & Wanderley, 2015), such as species of Alcantarea (see Figure 3c), comprise large water-storing tanks, that can accumulate considerable amounts of water per rosette (Lehmann et al., 2022), and usually comprise mesomorphic leaves covered sparsely with trichomes. It remains difficult to understand how old, large and heavy Alcantarea species attach themselves to VRWs.

Another remarkable characteristic is that, generally, hyperepilithic bromeliads possess prostrate stems that either grow strictly upwards (e.g. various species of Stigmatodon, Figure 3a, and Alcantarea) or downwards (e.g. Tillandsia araujei, Figure 3b). Consequently, hyperepilithics slowly creep across the vertical slopes. Further studies are necessary to better understand the particularities of hyperepilithics.

HYPEREPILITHICS ON PALEOTROPICAL INSELBERGS

In the Paleotropics, VRWs in dome-shaped inselbergs are frequent in Africa, for example around Idanre, Nigeria (Figure 4a), around Ambalavao, Madagascar (Figure 4c), and in India, near Bangalore (Figure 4b). In this region, VRWs are usually not colonized by vascular plants. Only very occasionally mat-forming, desiccation-tolerant Cyperaceae, such as Afrotrilepis pilosa in West Africa, and Coleochloa setifera in East Africa and Madagascar (Porembski, 2007), can be observed as colonizers (Figure 4c). These species, however, primarily grow on flat to slightly inclined rocky slopes.

HYPEREPILITHICS ON NEOTROPICAL TEPUIS AND PALEOTROPICAL ASIAN KARST FORMATIONS

Tepuis are considered a centre of richness and endemism of the neotropical flora (Riina et al., 2019). In the Pantepui, two main different rocky plant habitats are recognized: (i) the more or less flat summits that have been extensively studied in recent decades (e.g. Riina et al., 2019) and (ii) the vertical cliffs, that due to the difficult accessibility, almost nothing is known about its flora (Huber & Rull, 2019). It is possible that hyperepilithic species inhabit these vertical cliffs, considered here as VRWs, for example members of the Bromeliaceae. In the Pantepui, Bromeliaceae represent ancestral lineages within the family, such as Lindmania and Brochinia (Givnish et al., 2007). Another example is Pitcairnia patentiflora, a bromeliad endemic to the Pantepui and sister group to other lineages that widely diversified in the inselbergs of south-eastern Brazil (Givnish et al., 2007). Therefore, it would not be surprising to find hyperepilithic bromeliads (and perhaps other taxa) growing on VRWs of the Pantepui.

In the Paleotropics, vertical Karst habitats seem to occur mainly in southwestern China. There, the towers karst (fenglin) form large vertical walls, with towers over 100 m tall and a mean slope angle of 75° (Tang & Day, 2000). In Southeast Asia, karst occurs mainly in Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam, we expect that hyperepithics plants may occur in these vertical karst walls. However, published information is absent.

HYPEREPILITHICS AS A NEW SOURCE FOR FUTURE SUSTAINABLE URBAN VERTICAL GARDENING

The demand for ‘green nature’ and gardens, not only for aesthetical reasons but also with regards to environmental aspects of CO2 fixation and temperature control in our modern (mega-) cities, dominated by bare concrete architecture, has led to the concept of ‘vertical gardening’. One of the pioneers of vertical gardens was Roberto Burle Marx (Montero, 2001), but since then, the concept has worldwide gained great public attention (e.g. Davis et al., 2016; Lotfi et al., 2020).

Usually, climbers or hanging plants in particular containers are attached or integrated in building facades. The maintenance of these gardens is still a challenge concerning water and nutrient supply for plants. Hyperepilithics could open a completely new dimension for vertical gardens in the humid tropics: The plants can grow directly on the vertical concrete wall without continuous horticultural care or even containers. This could reveal new and unexpected aspects for ‘future cities’.

The best candidates will probably be hyperepilithics plants, from Brazilian inselbergs. According to our observations of natural vertical gardens, the hyperepilithic Bromeliads are most promising for urban vertical gardening: for example Alcantarea acuminatifolia, A. cerosa, A. robertokautskyi, A. simplicisticha, Stigmatodon costae, S. euclidianus, S. goniorachis, Tillandsia araujei, T. gardneri, T. graomogolensis, T. nuptialis, T. reclinata, Vriesea saundersii and V. botafogensis. Possibly, some other families could be interesting, for example epiphytic Cacti belonging to the genera Rhipsalis, Epiphyllum and Hylocereus.

The selection of suitable clones and breeding work will generate optimized candidates. On the contrary, architects and building constructors in cooperation with horticulturists have to develop optimized concrete architectural surfaces for the vertical gardening of these plants. It is a new challenge, but already the spatial dimension of concrete vertical walls in megacities like Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo or Singapore justifies high efforts for a sustainable green urban future.

CONCLUSIONS, CONSERVATION ASPECTS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

In this study, we demonstrate that VRWs represent a unique habitat type, colonized by hyperepilithic plants, represented mainly by Tillandsioid bromeliads. Even though VRWs are common features on inselbergs, characteristic species of this habitat are endangered due to increasing human activities. In particular, mining and the destruction and degradation of the flanking vegetation in the surrounding region for agriculture and urban development (Porembski et al., 2016) are particularly damaging to VRW species. Also, despite the difficult access to VRWs, recreational activities such as rock climbing can result in damage to the vascular hyperepilithic flora (Couto et al., 2022) as occurs for non-vascular plants (Clark & Hessl, 2015). Thus, climbers and mountaineering societies should be aware of this specialized plant group in the tropics and avoid opening new routes in regions rich in hyperepilithics. Future studies should concentrate on the phylogenetic (but see Couto et al., 2022) and functional aspects of hyperepilithic plants to understand why some of them are exclusive to VRWs while others are more variable in their habitat preferences. In addition, inventories and phytosociological data could be accessed using drones (see Lehmann et al., 2022) and by climbing techniques that enable sampling of VRWs, which were already described for cliff communities (Larson et al., 2000). In these respects, special attention should be paid to regions where data on the hyperepilithic flora is very limited, such as Amazonian inselbergs from northern Brazil and Colombia, the quartzite and sandstone rock outcrops of the Tepuis from Guiana Shield and the tropical Asian Karst formations. We also see a great potential of using hyperepilithics on vertical urban gardens. Finally, we hope to draw attention of researchers working on inselberg vegetation, as well as on other rocky type ecosystems, on the existence of the life form and encourage further studies on hyperepilithics in other parts of the world.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dayvid Rodrigues Couto: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); investigation (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Stefan Porembski: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (equal); investigation (lead); supervision (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Wilhelm Barthlott: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); investigation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Luiza de Paula: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); investigation (lead); supervision (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Vertical rock walls were first noticed by S. Porembski and W. Barthlott years ago, and their own fieldwork on inselbergs in both tropical and temperate regions has been necessary to fully understand the uniqueness of vertical rock walls as a habitat type. We would like to thank Doug S. Larson (Guelph), Mandar Datar and Aparna Watve (both Pune) for insightful discussions, which draw our attention to cliff ecosystems. This resulted in our description of this new inselberg habitat type. We express our gratitude to Peggy Fiedler for English proofreading. D.R. Couto thanks a research grant by the Nacional Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Programa de Capacitação Institucional—PCI/INMA—317789/2021-0) of the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI), and L.F.A. de Paula thanks the grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico-CNPq (150683/2022-7) and from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-CAPES (88887.569558/2020-00).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There is no conflict of interest to report.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data will be available on request.