Federal judge ideology, securities class action litigation, and stock price crash risk

Abstract

This study investigates whether and how federal judge ideology affects firm-specific stock price crash risk. Using a comprehensive sample of US firms, we find a decline in the likelihood of future stock price crashes for firms headquartered in more liberal circuits. In identifying potential mechanisms, we show that liberal judge ideology reduces information opacity, risk-taking behaviours and overinvestment, and thus curbs stock price crash risk. Furthermore, the curbing effect is more salient for firms with poor monitoring quality and those in low social capital areas. Overall, this study elucidates how federal judge ideology affects capital markets.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the global financial crisis, stock price crash risk (crash risk) has attracted increasing attention. The literature theorises that concerns about job security, performance-based incentive compensation and other contractual arrangements motivate managers to conceal negative information and maintain inflated stock prices (Ball, 2009; Hong et al., 2017; Jin & Myers, 2006; Kim et al., 2011a, 2011b). When accumulated negative information eventually reaches a tipping point, managers realise that the costs of hoarding behaviours exceed the associated benefits; thus, the stockpile of bad news is suddenly released, which leads to a large-scale, unforeseen decline in stock price or simply a stock price crash (Hutton et al., 2009; Jin & Myers, 2006). Stock price crashes damage investor confidence and lead to huge losses in investor wealth.

US securities laws play a crucial role in facilitating the effectiveness and stability of the US capital market (Roychowdhury & Srinivasan, 2019). Securities class action litigation is one of the most important mechanisms to protect outside investors from wealth loss. It thus could exert a significant influence on corporate policies and practices. A question arises: whether the likelihood of being sued in securities class action lawsuits affects managerial behaviours and how this impact extends to the capital market. Therefore, this study focuses on crash risk, a market-based measure that can comprehensively reflect managerial information manipulation (e.g., accrual manipulation, classification shifting, tax avoidance, off-balance sheet devices and earnings guidance) (Callen & Fang, 2017; Kim et al., 2011b). As the perceived litigation risk of a given firm largely depends on judge ideology in the corresponding circuit (Huang et al., 2019), we aim to provide systematic evidence from the perspective of judicial ideology, based on a large sample, for the effect of securities class action litigation risk on the likelihood of stock price crashes.

Class-action and derivative lawsuits are two primary types of legal recourse available to shareholders (Obaydin et al., 2021). Generally, securities class action lawsuits, the mechanism to enforce federal securities laws, directly allege securities fraud (e.g., disseminating misleading statements, making delayed disclosure, omitting material information). This kind of litigation is always filed by shareholders and leads to monetary compensation. By contrast, derivative lawsuits, the procedural mechanism to implement state fiduciary duty laws, allege managers' breach of fiduciary duties (e.g., engaging in illegal activities, self-dealing). The actual plaintiff of derivative litigation is corporate rather than shareholders (Huang et al., 2023). Prior studies document that the perceived risk from different shareholder litigation can affect corporate policies and practices differently (Bourveau et al., 2018; Houston et al., 2019). This study focuses on the litigation risk from securities class action lawsuits. For one thing, based on ‘fraud on the market’ theory, a one-time stock price slump tends to incur the filing of class-action lawsuits (Field et al., 2005; Francis et al., 1994). Therefore, we aim to move beyond derivative litigation which generally exerts influence through corporate governance (Bourveau et al., 2018; Dong & Zhang, 2019), and directly examine how ex-ante class-action litigation risk affects the likelihood of stock price crashes. For another, there is mixed evidence regarding the complementary relationship between the two types of shareholder litigation (Houston et al., 2018; Obaydin et al., 2021). Houston et al. (2018) found that the decrease in derivative litigation does not lead to an increase in class-action lawsuits. In this context, it is worthwhile to separate securities class action litigation and empirically interpret its impact on crash risk.

Judicial preferences to the investors are associated with a higher risk of securities class action lawsuits (Huang et al., 2019). We propose that perceived litigation risk can curb the likelihood of stock price crashes by reducing information opacity, constraining risk-taking behaviours, and deterring overinvestment, considering that bad news withholding and suboptimal investments are the primary inducements of stock price crashes (DeFond et al., 2015; Khurana et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2011b; Kim, Li, et al., 2016; Kim & Zhang, 2014). To be specific, based on the political science literature, circuit courts dominated by liberal ideology favour the interests of investors, while circuit courts, where conservative ideology prevails, favour ‘free and less regulated markets’ (Cross, 2007; Fedderke & Ventoruzzo, 2016; Sunstein et al., 2004). Therefore, a more liberal circuit court could pose a higher litigation threat to firms in the corresponding jurisdictions. Firms and their managers are incentivised to avoid securities action lawsuits because of high litigation costs (Cox, 1999; Field et al., 2005; Romano, 1991). Across class-action litigation, the issues frequently raised in claims are misleading statements and omitted material information disclosure. It can be assumed that, in a more liberal circuit, managers tend to disclose negative information in a timely manner to mitigate litigation concerns regarding reputation costs and potential employment termination. Thus, because the concealment of bad news is mitigated and information opacity is reduced, we expect a decline in crash risk for firms in liberal circuits. Additionally, perceived litigation risk can influence firms' operating and investment decisions (Li et al., 2023). In this regard, we consider that liberal judge ideology has a deterrent effect on inefficient investment and risk-taking behaviours, which also results in a lower likelihood of stock price crashes.

Conversely, a competing viewpoint suggests that higher litigation risk leads to higher crash risk. Specifically, for corporate defendants, being sued in class-action lawsuits is associated with negative market reactions (Bhagat et al., 1998; Koku, 2006). As litigation risk increases due to liberal judge ideology, the incidence of lawsuits may directly lead to a significant decline in stock prices. Given the opposing viewpoint, the directional effect of litigation risk on crash risk is ultimately a matter for empirical investigation.

However, measuring a firm's ex-ante litigation risk is challenging. Previous studies use industry membership as a major proxy for litigation risk, which includes industry and firm characteristics unrelated to litigation risk (Kim & Skinner, 2012). Huang et al. (2019) constructed a new measure based on federal judge ideology to capture a firm's external litigation environment, which is suggested as an efficient proxy for ex-ante litigation risk.1 Therefore, we calculate court liberalism following Huang et al. (2019). Specifically, we identify each judge's appointing president and measure court liberalism by calculating (1) the probability of appointees of Democratic presidents dominating a panel of three judges selected randomly from the circuit and (2) the proportion of appointees of Democratic presidents in a circuit court. Finally, we obtain a firm's litigation risk based on the degree of liberalism in the circuit in which it is headquartered.

We capture a firm's crash risk by (1) the negative skewness of firm-specific weekly returns (after netting out common returns) and (2) the asymmetric volatility of negative versus positive firm-specific returns (Callen & Fang, 2013, 2015a, 2015b; Chen et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2011a, 2011b; Kim, Wang, et al., 2016). Using a sample of 20,760 firm-years between 2008 and 2017, we find that liberal judge ideology is negatively associated with the likelihood of a firm experiencing future stock price crashes, which is statistically and economically significant.

Next, we perform tests to alleviate endogeneity concerns. Specifically, we construct matched samples comprising firms in high- and low-liberalism jurisdictions using an entropy-balanced technique and propensity score matching (PSM), respectively. We re-examine the association between liberal judge ideology and crash risk in these matched samples, and the results corroborate our baseline findings. In addition, we conduct analyses to verify that our results are robust to alternative measurements of crash risk and court liberalism, additional control variables and alternative sample selection. Overall, the aforementioned tests enhance the validity of the empirical evidence.

In our mechanism analyses, we observe that the curbing effect of liberal judge ideology on crash risk is concentrated in firms with less analyst coverage, firms with higher cash flow volatility, and firms engaged in more severe overinvestment, providing empirical evidence that liberal judge ideology can exert a deterrent effect on information opacity, risk-taking behaviours and overinvestment, and thus reduce crash risk. In our additional analyses, we examine the heterogeneity in the main effect. The results show that the negative association between liberal judge ideology and crash risk is more pronounced for firms with weak internal monitoring and firms located in regions with lower social capital.

This study contributes to existing literature in several ways. First, it extends the understanding of federal judge ideology by examining its effects on capital markets. The political science literature finds that judge ideology influences judicial votes in federal courts, with judges appointed by Democratic presidents being more protective of private plaintiffs and more in favour of government intervention than those appointed by Republican presidents (Cross, 2007; Sunstein et al., 2004). Drawing on this stream of research, Huang et al. (2019) proposed judge ideology as a new measure of ex-ante litigation risk, and Chen et al. (2022) and Huang et al. (2024) applied judge ideology to initial public offering (IPO) underpricing and insider trading, respectively. We provide further evidence on how judicial appointments affect the capital market through their impact on crash risk. Moreover, we demonstrate that judges play a gatekeeping role in the capital market (Roychowdhury & Srinivasan, 2019), with real economic consequences for firms regarding the political risk generated by judicial appointments and how firms proactively manage that risk.

Second, this study adds to the related literature by examining the determinants of crash risk. Prior studies investigate a series of internal corporate factors such as managerial compensation incentives, quality of financial reporting, structure of the managerial labour market and efficiency of internal monitoring (Chen et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2011b; Kim, Li, et al., 2016; Kim & Zhang, 2014). The literature on ways to mitigate crash risk mainly discusses the strength of external monitoring by outside stakeholders such as institutional investors (An & Zhang, 2013), analysts (Kim et al., 2019) and foreign investors (Kim et al., 2020). We contribute to this stream of research by identifying a critical external factor in firms' corresponding jurisdictions: judge ideology.

Apart from that, we complement Obaydin et al. (2021) who examine the association between the adoption of universal demand (UD) laws and crash risk. However, our study focuses on the litigation risk from securities class action lawsuits rather than derivative lawsuits. In general, class-action litigation directly alleges securities frauds such as disseminating misleading statements, making delayed disclosure and omitting material information. Compared to derivative litigation that exerts influence on corporate defendants through corporate governance reforms, class-action litigation can affect information manipulation more directly (Bourveau et al., 2018; Dong & Zhang, 2019). Furthermore, the complementary relationship between the two types of shareholder litigation is an open question. Obaydin et al. (2021) provided evidence that they complement each other, whereas Houston et al. (2018) found that the decrease in derivative litigation does not lead to an increase in class-action lawsuits. This study directly interprets the association between class-action litigation risk and the likelihood of stock price crashes, highlighting the distinction and relation between the two types of legal recourse.

The paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, we discuss the institutional background. In Section 3, we review the relevant literature and develop our research hypothesis. We describe the research design in Section 4 and present the empirical results in Section 5. Sections 6 and 7 provide the mechanism analyses and additional analyses. The final section concludes this study.

2 INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND

A securities class action lawsuit typically alleges that managers violate Rule 10b-5 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 by fraudulently making false or misleading statements and/or failing to disclose negative material information to the market in a timely manner (Niehaus & Roth, 1999). Securities class action lawsuits give shareholders the right to bring private actions in federal courts to recover damages caused by securities frauds. These lawsuits are very costly for both firms and managers. Aside from the settlement payouts, legal fees and procedural costs, litigation also leads to a significant decline in stock price, increased directors' and officers' (D&O) insurance premiums, as well as distraction from business routine, damaged reputation and potential termination for managers (Bhagat et al., 1998; Cox, 1999; Donelson & Yust, 2019; Field et al., 2005; Hutton et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2000; Romano, 1991). Therefore, avoiding involvement in securities class action lawsuits is attached great emphasis.

In the US judicial system, there are 94 district courts (trial courts) and 12 circuit courts (courts of appeal).2 In a class action lawsuit, the plaintiff first files a complaint against the defendant in one of these 94 district courts, depending on the location of the defendant firm's headquarters.3 In the district court, dismissal and out-of-court settlement are the commonest outcomes, while trial verdict and summary judgment are rare for such lawsuits (Choi et al., 2013). If a case is dismissed in the district court, a plaintiff can appeal the decision to the appropriate circuit court, and the case is assigned to a panel of three judges selected at random. The decision rests with the panel's majority opinion, namely, at least two of the three judges on the panel must agree with the decision.4

What matters most for decisions on lawsuits are the votes of judges in the circuit courts. Therefore, we focus on a vital determinant of judicial votes: judge ideology (Bonica & Sen, 2021; Helland, 2019). Judges in all federal courts are appointed by the President of the United States, subject to the approval of the US Senate. Presidents always appoint judges whose ideology reflects that of their own political party, with the result that judicial outcomes tend to be consistent with the president's own policy preferences (Dorsen, 2006; Federal Judicial Center, 2006). Following their appointments, federal judges have guaranteed tenure and salary (Federal Judicial Center, 2006), which ensures the independence of the judiciary and enables judges to vote according to their political inclination. In addition, although legal doctrine appears to play an important role in deciding case outcomes, judges are more (less) likely to follow legal doctrine when that doctrine supports (conflicts with) their partisan or ideological policy preferences (Cross & Tiller, 1998). And following the Tellabs ruling (Cox et al., 2009; Miller, 2009), judges have increasingly high levels of discretion in judicial decision making, providing a further reason for them to vote in accordance with their ideology.

It is well documented in the political science literature that judge ideology influences judicial votes in federal courts, with judges appointed by Democratic presidents more liberal than those appointed by Republican presidents (Cross, 2007; Sunstein et al., 2004). Democratic (liberal) ideology results in outcomes that are to the benefit of the ‘have-nots’, while Republican (conservative) ideology results in outcomes that are to the benefit of the ‘haves’. Applying the ‘liberal versus conservative’ coding protocol to securities class action lawsuits, studies find that liberal judges are more likely to vote in favour of investors (as plaintiffs), whereas conservative judges favour ‘free and less regulated markets’ and are more likely to vote in support of firms (as defendants) (Fedderke & Ventoruzzo, 2016; Grundfest & Pritchard, 2002; Sullivan & Thompson, 2004). Huang et al. (2019) found that firms headquartered in more liberal circuits (namely, circuits where Democratic judges dominate) are more likely to be sued and that securities class action lawsuits filed in those circuits are less likely to be dismissed; firms also have to accept higher settlement amounts. As such, judges with liberal ideology pose a higher litigation risk than conservative judges to firms headquartered in the corresponding circuit.5

3 RELATED LITERATURE AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

Our study seeks to extend the line of research that examines the role of judge ideology in the capital market context, focusing particularly on its impact on crash risk. Specifically, motivated by equity incentives, career concerns and empire-building (Ali et al., 2019; Ball, 2009; Benmelech et al., 2010; Kothari et al., 2009), managers can strategically withhold bad news and/or delay its release to external stakeholders (Kothari et al., 2009), leading to the stockpiling of negative information and increasing the likelihood of stock price crashes (Hong et al., 2017; Hutton et al., 2009; Jin & Myers, 2006). In other words, when reaching a tipping point, a large amount of negative information is suddenly released into the market, resulting in an abrupt, large-scale decline in stock price or simply a crash in the stock price (Hutton et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011a). Nor is manager misbehaviour limited to hoarding bad news; to support an illusion of strong performance and growth opportunities, managers can choose suboptimal investment policies or risk-taking behaviours (Kedia & Philippon, 2009; McNichols & Stubben, 2008). Overinvestment during periods of inflated performance can also lead to undercapitalisation and cause stock price crashes (Benmelech et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2011b).

Based on the discussion in Section 2, securities class-action lawsuits are more likely to be filed, less likely to be dismissed, and more likely to result in high-value settlements in liberal circuits (Huang et al., 2019). In other words, firms headquartered in such jurisdictions could perceive a substantial litigation threat due to the liberal judges' dominance in the circuit court. We argue that the litigation threat posed by the liberal judge ideology reduces the likelihood of stock price crashes for the following reasons.

First, the litigation threat from judges' liberal ideology could heighten managers' concerns about litigation costs, deter managers from hoarding bad news and thus reduce crash risk. Higher litigation risk could increase the costs of concealing bad news, encourage timely disclosure and reduce opacity, which is related to the pre-emption effect of litigation threat (Skinner, 1994, 1997). For example, Houston et al. (2019) found a positive association between perceived class-action litigation risk and voluntary disclosure, especially disclosure conveying negative information. Huang et al. (2019) found that firms facing higher class-action litigation risk are more likely to issue earnings warnings. Since liberal judges are to the benefit of plaintiffs (investors) rather than to the benefit of defendants (firms), investors could be willing to file class action lawsuits to protect their rights and interests, and neither dismissal decisions nor outcomes are likely to be in favour of the ‘haves’. For firms in the liberal circuit, deliberate concealment behaviour is more likely to incur class-action lawsuits.6 The perceived litigation risk due to liberal judge ideology mitigates managerial incentives for withholding bad news by enhancing the concerns regarding penalties, damaged reputation and even potential termination. Managers tend to pre-empt bad news and update market expectations with their material private information in a timely manner (Heitzman et al., 2010), and thus lower the likelihood of stock price crashes.

In addition, although the above discussion focuses on how the threat posed by liberal judge ideology reduces the crash risk by deterring the hoarding of bad news and improving information transparency, perceived litigation risk can also reduce crash risk through its impact on real decision-making. Arena and Julio (2015) found that corporate operating and investment decisions are affected by litigation risk, as firms increase cash holdings and reduce their capital expenditures in response to risk, implying that firms exposed to litigation risk could be cautious in future business activities. Thus, the litigation threat resulting from judges' liberal ideology could deter inefficient corporate investment and risk-taking behaviour and reduce the likelihood of stock price crashes.

The above discussions lead to the following hypothesis:

H1.All other things being equal, the ex-ante litigation risk caused by liberal judge ideology is negatively associated with the likelihood of stock price crashes.

Meanwhile, prior literature argues that litigation risk has a chilling effect on corporate disclosure. Specifically, in face of high litigation risk, managers may be reluctant to make voluntary disclosures because investors can use the information provided in the disclosure as a rationale for bringing a lawsuit (Francis et al., 1994; Johnson et al., 2001; Rogers & Van Buskirk, 2009). Huang et al. (2019) found that litigation risk reduces positive long-horizon management forecasts. However, issuing upward-biased forecasts can be a way to camouflage bad news (Hermalin & Weisbach, 2012). Long-term optimistic guidance is generally associated with greater agency conflicts and eventually leads to higher crash risk (Hamm et al., 2012). Therefore, the chilling effect that class-action litigation risk deters long-term positive earnings guidance is not mutually exclusive with H1.

Nevertheless, counterarguments suggest that the effect of liberal judge ideology on crash risk may go in the other direction. Specifically, for the defendant firms, being sued in class-action lawsuits is associated with negative market reactions (Bhagat et al., 1998; Johnson et al., 2000; Koku, 2006). In more liberal circuits, securities class action lawsuits are more likely to be filed and less likely to be dismissed. The actual occurrence of class-action litigation directly results in a significant decline in stock prices of corporate defendants. In this case, the association between ex-ante litigation risk caused by liberal judge ideology and the likelihood of stock price crashes remains an open issue.

4 SAMPLE AND RESEARCH DESIGN

4.1 Sample and data source

We obtain the Federal Judicial Center website's biographical data on circuit court judges. Our initial sample is drawn from the intersection of the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) and Compustat databases. In addition to deleting observations with missing data, we also exclude those with (1) non-positive book value and total assets, (2) fiscal year-end prices less than $1, and (3) fewer than 26 weeks of stock return data. After applying these selection criteria, we obtain a sample of 20,760 firm-year observations from 2008 to 2017 for the main regressions.7

4.2 Measuring firm-specific crash risk

Our second measure is the asymmetric volatility of negative versus positive returns. For each firm j over a fiscal year t, we separate all the weeks with firm-specific weekly returns below the annual mean (‘down’ weeks) from those with firm-specific returns above the annual mean (‘up’ weeks) and calculate the standard deviation for each subsample. The variable DUVOLj,t is the log of the ratio of the standard deviation on the down weeks to the standard deviation on the up weeks.

4.3 Measuring federal judge ideology

4.4 Empirical design

In Equation (4), the dependent variable CrashRiskt+1 is one of the proxies for crash risk: NCSKEWt+1 and DUVOLt+1. All independent variables are measured in year t. The key variables of interest, LIB_COURT and LIB_JUDGE, are proxies for ex-ante litigation risk; they capture the probability of appointees of Democratic presidents dominating a panel of three judges selected at random from the circuit and the percentage of judges appointed by Democratic presidents in the circuit, respectively.

We include in Equation (4) a set of control variables including detrended turnover (DTURN), negative conditional return skewness (NCSKEW), return volatility (SIGMA), average firm-specific returns (RET), firm size (SIZE), market-to-book ratio (MB), financial leverage (LEV), profitability (ROA) and average absolute discretionary accruals (ACCM), taken from Chen et al. (2001), Hutton et al. (2009) and Kim et al. (2011a, 2011b). Continuous variables are winsorised at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of outliers. Appendix 1 provides detailed definitions of the variables. In addition, we include year fixed effects to control for time-varying macroeconomic conditions and regulatory environments, as well as firm fixed effects to mitigate the concern that time-invariant firm-specific characteristics drive our main findings. Standard errors are adjusted for heteroscedasticity and clustered at the state level.9

5 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

5.1 Descriptive statistics

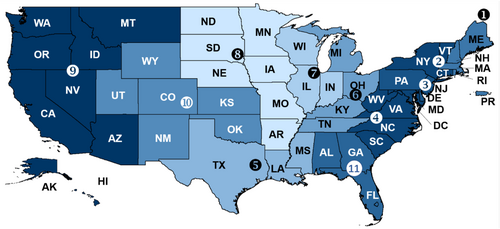

Appendix 2 reports our measure of federal judge ideology (LIB_COURT) by circuit and year. Judge ideologies vary significantly across circuits. In the 9th circuit, known as the most liberal circuit, the mean of LIB_COURT is 0.724; that is, there is a 72.4% chance that liberal judges will dominate a three-judge panel selected at random from that circuit. At the other extreme, in the 8th circuit, the most conservative circuit during the sample period, the mean of LIB_COURT is 0.074; that is, there is only a 7.4% chance that liberal judges will dominate a three-judge panel selected at random from that circuit. Additionally, although circuit court judges have a lifetime tenure, the ideology of a circuit judge panel can change dramatically over time because of the continuous cycle of terminations and appointments. For example, the 1st circuit was dominated by conservative judges until 2012 (LIB_COURT was lower than 0.5 in the preceding years) but was decidedly liberal from 2013 to 2017 (LIB_COURT was higher than 0.5). Figure 1 shows the geographic boundaries of the 12 circuits and the average LIB_COURT at the circuit level for 2008–2017. Darker shades indicate a higher degree of liberalism.

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics of the sample of 20,760 observations. The means of NCSKEWt+1 and DUVOLt+1 are 0.057 and −0.023, respectively. The descriptive statistics for the regression variables are comparable to those reported in other studies.

| Variable | Mean | SD | P10 | P25 | Median | P75 | P90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCSKEW t+1 | 0.057 | 0.870 | −0.915 | −0.428 | 0.014 | 0.487 | 1.075 |

| DUVOL t+1 | −0.023 | 0.387 | −0.507 | −0.280 | −0.035 | 0.225 | 0.473 |

| LIB_COURT | 0.481 | 0.251 | 0.151 | 0.237 | 0.533 | 0.696 | 0.778 |

| LIB_JUDGE | 0.487 | 0.164 | 0.270 | 0.333 | 0.519 | 0.628 | 0.679 |

| DTURN | −0.099 | 0.524 | −0.661 | −0.287 | −0.013 | 0.212 | 0.413 |

| SIGMA | 0.051 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.031 | 0.044 | 0.063 | 0.088 |

| RET | −0.169 | 0.217 | −0.383 | −0.194 | −0.095 | −0.047 | −0.025 |

| SIZE | 6.641 | 2.022 | 3.903 | 5.256 | 6.649 | 8.007 | 9.289 |

| MB | 3.286 | 3.970 | 0.877 | 1.317 | 2.094 | 3.606 | 6.345 |

| LEV | 0.477 | 0.216 | 0.176 | 0.309 | 0.483 | 0.640 | 0.760 |

| ROA | −0.001 | 0.173 | −0.166 | −0.011 | 0.038 | 0.077 | 0.124 |

| ACCM | 4.594 | 12.228 | 0.098 | 0.221 | 0.731 | 3.029 | 10.270 |

- Note: This table presents the descriptive statistics (Obs. = 20,760). All continual variables are winsorised at the top and bottom 1st percentiles. See Appendix 1 for variable definitions.

5.2 Main regressions

Table 2 presents the results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression results for Equation (4). The key variables of interest are LIB_COURT in columns (1) and (3) and LIB_JUDGE in columns (2) and (4). Note that our dependent variables are NCSKEWt+1 and DUVOLt+1 in columns (1) and (2) and columns (3) and (4), respectively. Table 2 shows that the coefficients of LIB_COURT and LIB_JUDGE are negative and highly significant at the 0.01 level. To assess the economic significance of the results, following Callen and Fang (2015a), we set LIB_COURT to shift by 1% and hold all other variables at their mean values; an increase of 1% in the probability of liberal judges dominating a selected panel (LIB_COURT) is related to 3.04% and 3.39% decreases in the average levels of NCSKEWt+1 and DUVOLt+1, respectively. From another perspective, the coefficients of LIB_JUDGE imply that an additional liberal judgment on the average circuit is associated with declines of 13.83% and 15.43% in the average levels of NCSKEWt+1 and DUVOLt+1, respectively.10 Thus, the curbing effect of liberal judge ideology on crash risk is statistically and economically significant.

| Dependent variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| LIB_COURT | −0.173*** | −0.078*** | ||

| (−2.70) | (−2.85) | |||

| LIB_JUDGE | −0.302*** | −0.136*** | ||

| (−2.77) | (−2.87) | |||

| DTURN | 0.039*** | 0.039*** | 0.017*** | 0.017*** |

| (3.67) | (3.68) | (3.53) | (3.53) | |

| NCSKEW | −0.120*** | −0.120*** | −0.052*** | −0.052*** |

| (−17.02) | (−17.01) | (−17.88) | (−17.87) | |

| SIGMA | 0.934 | 0.940 | 0.454 | 0.456 |

| (0.75) | (0.76) | (0.78) | (0.79) | |

| RET | 0.176 | 0.177 | 0.092 | 0.092 |

| (1.06) | (1.06) | (1.22) | (1.22) | |

| SIZE | 0.259*** | 0.259*** | 0.124*** | 0.124*** |

| (9.65) | (9.64) | (10.31) | (10.31) | |

| MB | −0.004 | −0.004 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| (−1.38) | (−1.38) | (−0.99) | (−0.99) | |

| LEV | 0.092 | 0.092 | 0.017 | 0.017 |

| (0.99) | (0.99) | (0.43) | (0.44) | |

| ROA | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.051 | 0.051 |

| (0.79) | (0.78) | (1.67) | (1.67) | |

| ACCM | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.24) | (0.24) | (0.21) | (0.21) | |

| Constant | −1.618*** | −1.554*** | −0.817*** | −0.788*** |

| (−7.43) | (−7.00) | (−8.56) | (−8.09) | |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 20,760 | 20,760 | 20,760 | 20,760 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.076 | 0.076 | 0.084 | 0.084 |

- Note: This table reports the results of regressing crash risk on federal judge ideology. Year and firm dummies are included in all regressions. The t-values in parentheses are based on standard errors that are adjusted for heteroscedasticity and clustered by state. *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.10, 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively. See Appendix 1 for variable definitions. The bold values in parentheses are t-statitics.

These findings suggest that crash risk is relatively low when the ideology of federal circuit court judges is liberal. Overall, the results in Table 2 support H1, confirming that liberal judges are perceived as imposing higher litigation risk on firms, thereby mitigating the probability of a stock price crash.

5.3 Mitigating endogeneity concerns

It is plausible that firms headquartered in high-liberal jurisdictions have different characteristics from those headquartered in low-liberal jurisdictions. To control for these differences, we construct matched samples using the entropy balancing technique and the PSM approach, respectively, to re-examine the effect of judge ideology, and the results are reported in Table 3. We classify an observation into a high-liberalism group if LIB_COURT is above 0.5 and a low-liberalism group if LIB_COURT is below 0.5. First, we estimate our main specification using an entropy-balanced sample and include all the control variables in Equation (4). Entropy balancing reweighted each observation in the low-liberalism group to ensure that the mean value, variance and skewness of all covariates are not statistically different between the high- and low-liberalism groups. As shown in columns (1) and (2) of Panel A, the coefficients of LIB_COURT are all negative and significant at 0.05. Additionally, we use a logit model that includes all the control variables in the baseline regression to estimate the propensity for a firm-year in the high-liberalism group. We then match each firm-year in the high liberalism group to one observation in the low liberalism group in the same industry and year. The matching procedure yields 2542 firm-year pairs.11 We re-examine the association between liberal judge ideology and crash risk in the PSM sample. As shown in columns (3) and (4) of Panel A, the coefficients of LIB_COURT are all negative and significant at the 0.01 level. In Panel B, the matched samples are constructed based on LIB_JUDGE, and our main findings hold. These tests mitigate endogeneity concerns and provide further evidence to support H1.

| Dependent variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Entropy balanced sample | PSM sample | |||

| Panel A: Using LIB_COURT as the judge ideology measure | ||||

| LIB_COURT | −0.177** | −0.070** | −0.773*** | −0.340*** |

| (−2.39) | (−2.29) | (−3.36) | (−3.36) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 20,760 | 20,760 | 5084 | 5084 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.085 | 0.092 | 0.162 | 0.170 |

| Panel B: Using LIB_JUDGE as the judge ideology measure | ||||

| LIB_JUDGE | −0.297** | −0.117** | −0.794** | −0.344** |

| (−2.36) | (−2.23) | (−2.48) | (−2.45) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 20,760 | 20,760 | 4952 | 4952 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.085 | 0.092 | 0.160 | 0.179 |

- Note: This table reports regression results for matched samples that ensure balance between observations with high- and low-liberalism. Panel A (Panel B) presents the results of using LIB_COURT (LIB_JUDGE) as the judge ideology measure. Year and firm dummies are included in all regressions. The t-values in parentheses are based on standard errors that are adjusted for heteroscedasticity and clustered by state. *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.10, 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively. The bold values in parentheses are t-statitics.

5.4 Robustness checks

5.4.1 Alternative measure of crash risk

We perform a battery of robustness checks to verify the results. First, we employ an alternative measure of crash risk. Specifically, CRASHt+1 is a dummy variable that equals one if there is at least 1 week with firm-specific weekly returns of 3.09 standard deviations (chosen to generate a probability of 0.1% in the normal distribution) below the annual mean weekly return during the measurement window, and zero otherwise. We replace CrashRiskt+1 with CRASHt+1 in Equation (4) and rerun the regressions. Table 4, Panel A reports the results, and our main findings hold.

| Panel A: Alternative crash risk measure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable = CRASHt+1 | ||

| (1) | (2) | |

| LIB_COURT | −0.076* | |

| (−1.82) | ||

| LIB_JUDGE | −0.133* | |

| (−1.90) | ||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes |

| N | 20,760 | 20,760 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.058 | 0.058 |

| Panel B: Alternative judge ideology measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||||

| NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| LIB_COURT1 | −0.279 ** | −0.126 *** | ||||

| (−2.29) | (−2.68) | |||||

| LIB_JUDGE1 | −0.452 ** | −0.210 *** | ||||

| (−2.43) | (−2.86) | |||||

| CF_SCORE | −0.213 *** | −0.092 *** | ||||

| (−3.08) | (−3.37) | |||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 20,760 | 20,760 | 20,760 | 20,760 | 20,760 | 20,760 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.076 | 0.084 | 0.084 | 0.084 |

- Note: This table presents the results for robustness checks regarding alternative crash risk and judge ideology measures, which are reported in Panels A and B, respectively. CRASHt+1 is a dummy variable which is equal to one if there is at least 1 week with firm-specific weekly returns 3.09 standard deviations below the annual mean weekly return during the measurement window, and zero otherwise. The calculation of LIB_COURT1 (or LIB_JUDGE1) is similar to LIB_COURT (or LIB_JUDGE), which includes the senior judges. CF_SCORE is another alternative federal judge ideology measure, which is based on political contributions of judges. Year and firm dummies are included in all regressions. The t-values in parentheses are based on standard errors that are adjusted for heteroscedasticity and clustered by state. *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.10, 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively. The bold values in parentheses are t-statitics.

5.4.2 Alternative measures of court liberalism

Second, we examine whether our main results are robust to alternative measures of court liberalism. Thus far, our analyses have excluded senior judges, who can take a reduced caseload. For robustness checks, we reconstruct the variables LIB_COURT1 and LIB_JUDGE1 to include senior judges. Table 4, Panel B reports the regression results. The coefficients of LIB_COURT1 and LIB_JUDGE1 are negative and statistically significant in columns (1) and (2) and columns (4) and (5), suggesting that the results are robust to whether senior judges are excluded from court liberalism measures.

In addition, we use the partisanship of judges' nominating presidents in the main regressions to measure judges' ideologies. In this subsection, we consider a strategy for measuring judicial ideology that uses the political contributions made by judges (Bonica & Sen, 2021) based on the logic that donors always prefer candidates with whom they are ideologically aligned (Bonica, 2014). Bonica and Sen (2017) applied a campaign finance-based methodology to federal judges and estimate common space (CF) scores, which continuously range from −2 to +2. A higher CF score indicates a more conservative ideology. We first assign each judge a CF score developed by Bonica and Sen (2017). Then, to obtain the firm-year-level alternative judge ideology measure, we take the average scores across all active judges in a given circuit court and measurement window. The average scores are multiplied by −1 to get CF_SCORE, and thus, a higher value of CF_SCORE indicates that the firm is located in a more liberal circuit. Columns (3) and (6) of Table 4, Panel B report the regression results. The coefficients of CF_SCORE are negative and statistically significant, suggesting that the negative association between liberal judge ideology and crash risk persists if judicial ideology is estimated using campaign contributions.

5.4.3 Additional control variables

Next, based on findings in prior literature, we add several variables that could potentially influence crash risk to the baseline regressions. Table 5, Panel A presents these results. In columns (1) and (2), we further control for the firm age (AGE), going concern opinion (GCOS), cash ratio (CASH) as well as dividend rate (DIV) (Andreou et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2020); in columns (3) and (4), we add several corporate governance factors, CEO-chairman duality (DUAL), internal control material weaknesses (ICMW), boardroom size (BRDSIZE) and boardroom independence (INDP) (Chen et al., 2017, 2021); in columns (5) and (6), we include tax avoidance measure (ETR) and social capital index (SK) in the regressions (Kim et al., 2011a; Li et al., 2017). The coefficients on LIB_COURT are negative and statistically significant. These results are not materially affected if LIB_JUDGE serves as the judge ideology measure (untabulated).

| Panel A: Additional control variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||||

| NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Firm-specific characteristics | Corporate governance factors | Tax avoidance and social capital | ||||

| LIB_COURT | −0.170 ** | −0.077 *** | −0.172 ** | −0.080 *** | −0.157 ** | −0.074 ** |

| (−2.60) | (−2.74) | (−2.64) | (−2.80) | (−2.37) | (−2.58) | |

| AGE | −0.019 | −0.010 | ||||

| (−0.37) | (−0.44) | |||||

| GCOS | 0.026 | 0.017 | ||||

| (0.26) | (0.38) | |||||

| CASH | −0.115* | −0.031 | ||||

| (−1.69) | (−1.06) | |||||

| DIV | 0.485 | 0.167 | ||||

| (1.59) | (1.21) | |||||

| DUAL | −0.024 | −0.011 | ||||

| (−1.05) | (−1.14) | |||||

| ICMW | 0.010 | 0.005 | ||||

| (0.30) | (0.31) | |||||

| BRDSIZE | −0.005 | −0.004 | ||||

| (−0.10) | (−0.19) | |||||

| INDP | 0.023 | 0.023 | ||||

| (0.23) | (0.53) | |||||

| ETR | 0.002 | 0.001 | ||||

| (0.21) | (0.26) | |||||

| SK | −0.048 | −0.013 | ||||

| (−1.40) | (−0.91) | |||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 20,760 | 20,760 | 19,991 | 19,991 | 20,760 | 20,760 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.075 | 0.084 | 0.076 | 0.081 | 0.075 | 0.084 |

| Panel B: Alternative sample selection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Isolate the effect of global financial crisis | Exclude observations in the 9th circuit | |||

| LIB_COURT | −0.153 ** | −0.083 *** | −0.173 ** | −0.079 ** |

| (−2.27) | (−2.96) | (−2.50) | (−2.65) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 18,699 | 18,699 | 16,065 | 16,065 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.080 | 0.091 | 0.074 | 0.082 |

- Note: This table presents the results for robustness checks regarding additional control variables and alternative sample selection, which are reported in Panels A, and B, respectively. Additional firm-specific controls include firm age (AGE), going concern opinion (GCOS), cash ratio (CASH) and dividend rate (DIV); additional corporate governance controls include CEO-chairman duality (DUAL), internal control material weaknesses (ICMW), boardroom size (BRDSIZE) and boardroom independence (INDP). Apart from that, GAAP effective tax rate (ETR) is used to measure tax avoidance, and social capital index (SK) from the Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development (NRCRD) is used to measure social capital. Different numbers of observations result from missing values or sample selection. Year and firm dummies are included in all regressions. The t-values in parentheses are based on standard errors that are adjusted for heteroscedasticity and clustered by state. *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.10, 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively. The bold values in parentheses are t-statitics.

5.4.4 Alternative sample selection

Finally, we check whether the main findings are sensitive to alternative sample selection, and the results are reported in Table 5, Panel B. We isolate the potential influence of the global financial crisis, which propagated a large negative price shock in the market, by excluding 2008. As columns (1) and (2) show, the signs and significance of the coefficients of LIB_COURT remain unchanged. Additionally, because the 9th circuit has the largest number of liberal judges and firms, we exclude the observations in this circuit and rerun the regressions. As columns (3) and (4) show, the coefficients of LIB_COURT remain negative and statistically significant. The findings in Table 5, Panel B persist if LIB_JUDGE serves as the judge ideology measure (untabulated). Overall, these robustness checks enhance the validity of the empirical evidence.

6 MECHANISM ANALYSES

6.1 Reducing information opacity

One of the key points underlying H1 is that liberal judge ideology in the corresponding jurisdiction curbs the managerial concealment of private negative information and improves transparency, thus reducing crash risk. The literature suggests that higher analyst coverage is associated with less earnings manipulation and information asymmetry in the equity market (Lang et al., 2003; Yu, 2008). Therefore, we employ analyst coverage (ANA) as a proxy for information asymmetry. We classify observations with ANA below the median into a subgroup with more opacity, whereas the other observations are classified into subgroups with less opacity. We then conduct separate regressions, and the results are reported in Table 6, Panel A.12 Regardless of how we measure crash risk, the coefficient of LIB_COURT is negative and statistically significant for the low ANA subsample while insignificant for the high ANA subsample. Moreover, the difference in the coefficients of LIB_COURT is statistically significant between the two subsamples, which means that the curbing effect of liberal judge ideology is more pronounced for firms with greater opacity. These results provide evidence for the argument that liberal judge ideology can lower crash risk by improving information transparency.

| Panel A: Information opacity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | |||

| Low ANA | High ANA | Low ANA | High ANA | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| LIB_COURT | −0.265*** | −0.098 | −0.121*** | −0.048 |

| (−2.68) | (−0.94) | (−2.82) | (−1.03) | |

| Coef test: |diff| | 0.167* | 0.073* | ||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,650 | 9872 | 10,650 | 9872 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.091 | 0.064 | 0.099 | 0.066 |

| Panel B: Risk taking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | |||

| High CFVOL | Low CFVOL | High CFVOL | Low CFVOL | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| LIB_COURT | −0.293** | −0.049 | −0.130*** | −0.019 |

| (−2.54) | (−0.44) | (−2.80) | (−0.34) | |

| Coef test: |diff| | 0.244** | 0.112** | ||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 9714 | 9711 | 9714 | 9711 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.077 | 0.086 | 0.088 | 0.090 |

| Panel C: Overinvestment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | |||

| High ABINV | Low ABINV | High ABINV | Low ABINV | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| LIB_COURT | −0.231** | −0.060 | −0.119*** | −0.028 |

| (−2.17) | (−0.59) | (−2.77) | (−0.62) | |

| Coef test: |diff| | 0.171* | 0.091** | ||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,105 | 10,105 | 10,105 | 10,105 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.079 | 0.075 | 0.084 | 0.079 |

- Note: This table reports the results for mechanism analyses. The results of information opacity channel, risk-taking behaviours channel and overinvestment channel are reported in Panels A, B and C, respectively. ANA, CFVOL and ABINV are proxies for analyst coverage, operating cash flow volatility and overinvestment, respectively. Different numbers of total observations result from missing values. Year and firm dummies are included in all regressions. The t-values in parentheses are based on standard errors that are adjusted for heteroscedasticity and clustered by state. *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.10, 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively. The bold values in parentheses are t-statitics.

6.2 Constraining risk-taking behaviours

We propose that liberal judge ideology could constrain managerial risk-taking and reduce crash risk. We calculate cash flow volatility as the standard deviation of operating cash flows (scaled by total assets) over the past 5 years (CFVOL) to capture corporate risk-taking behaviours. A higher cash flow volatility indicates managers are more willing to take risks. We classify observations with CFVOL above the median into a subgroup with more risk-taking, while the other observations are classified into a subgroup with less risk-taking. The results of separate regressions are reported in Table 6, Panel B. For both measures of crash risk, the coefficient of LIB_COURT is negative and statistically significant only for the high CFVOL subsample. The difference in the coefficients of LIB_COURT is statistically significant between the high CFVOL and low CFVOL subsamples, indicating that the effect of the liberal judge ideology on crash risk is more salient for firms with more risk-taking behaviours. These results confirm that liberal judge ideology can constrain risk-taking behaviours and thus reduce crash risk.

6.3 Deterring overinvestment

Corporate overinvestment is a major source of underperformance, negative news and another factor in the likelihood of stock price crashes. We consider that the litigation threat posed by liberal judge ideology could reduce the tendency for managers to overinvest and, therefore, lower crash risk. We obtain a measure of overinvestment (ABINV) from Richardson (2006), in which a higher value of ABINV indicates a more severe overinvestment problem.13 Similarly, we partition the full sample based on the median of ABINV and conduct separate regressions. As shown in Table 6, Panel C, for both measures of crash risk, the coefficient of LIB_COURT is negative and statistically significant for the subsample with high ABINV, while it is insignificant for the subsample with low ABINV. Furthermore, the difference in the coefficients of LIB_COURT is statistically significant between the high ABINV and low ABINV subsamples, suggesting that the curbing effect of liberal judge ideology on crash risk is concentrated in firms engaged in more severe overinvestment. These results indicate that firms located in jurisdictions with a higher level of liberalism can inhibit overinvestment, leading to a reduced likelihood of stock price crashes.

7 ADDITIONAL ANALYSES

To gain a deeper understanding of the role of judge ideology, we examine heterogeneity in the association between court liberalism and crash risk from two other governance mechanisms: boardroom independence and social capital.

7.1 The role of internal monitoring: Independent board

Effective internal monitoring can improve the information environment and deter managers from opportunistic investment, operating and disclosure behaviours. We predict that the curbing effect of liberal judge ideology on crash risk is more salient for firms with weak internal monitoring. As it is well documented that independent boards are associated with more effective monitoring roles and improved reporting and disclosure practices (Aggarwal et al., 2011; Armstrong et al., 2014), we employ boardroom independence (INDP) to capture the quality of internal monitoring and partition the full sample based on the median of INDP. Table 7, Panel A reports the results of separate regressions.14 In columns (1) and (2), we find that the coefficient of LIB_COURT is negative and statistically significant for the low INDP subsample and insignificant for the high INDP subsample. The difference in the coefficients of LIB_COURT is statistically significant between the two subsamples. These findings hold in columns (3) and (4) when DUVOL is the dependent variable. Collectively, the curbing effect of the liberal judgment ideology on the likelihood of stock price crashes is concentrated in firms with weak internal monitoring.

| Panel A: Internal monitoring | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| NCSKEW t+1 | DUVOL t+1 | |||

| Low INDP | High INDP | Low INDP | High INDP | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| LIB_COURT | −0.365*** | −0.076 | −0.173*** | −0.026 |

| (−2.69) | (−0.56) | (−2.91) | (−0.45) | |

| Coef test: |diff| | 0.289*** | 0.146*** | ||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,258 | 10,043 | 10,258 | 10,043 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.080 | 0.081 | 0.090 | 0.088 |

| Panel B: Informal institution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| NCSKEWt+1 | DUVOLt+1 | |||

| Low SK | High SK | Low SK | High SK | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| LIB_COURT | −0.290*** | −0.033 | −0.119*** | −0.031 |

| (−2.85) | (−0.34) | (−3.04) | (−0.67) | |

| Coef test: |diff| | 0.256*** | 0.088** | ||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm/Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,517 | 10,243 | 10,517 | 10,243 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.082 | 0.080 | 0.087 | 0.088 |

- Note: This table reports the results for additional analyses. The effects of internal monitoring and informal institution on the curbing effect of liberal judge ideology are shown in Panels A and B, respectively. The subsamples are divided based on the medians of the proportion of independent directors (INDP) and social capital index (SK), respectively. Different numbers of total observations result from missing values. Year and firm dummies are included in all regressions. The t-values in parentheses are based on standard errors that are adjusted for heteroscedasticity and clustered by state. *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.10, 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively. The bold values in parentheses are t-statitics.

7.2 The role of informal institution: Social capital

Next, we focus on social capital, which captures the strength of social norms and the density of associational networks in a given region (Guiso et al., 2004). Studies find that opportunistic managerial behaviours can be constrained, and agency conflicts can be mitigated, when firms are headquartered in regions with higher levels of social capital (Hasan et al., 2017; Hoi et al., 2019). Thus, we predict that the negative association between liberal judge ideology and crash risk is more pronounced for firms in low social capital environments. We obtain the social capital index (SK) from the Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development (NRCRD) and partition the full sample based on the median of SK. The results of separate regressions are reported in Table 7, Panel B. Similarly, the coefficient of LIB_COURT is negative and statistically significant only for the subsample with low social capital. The difference in the coefficients of LIB_COURT is statistically significant between the low SK and high SK subsamples, indicating that liberal judge ideology plays a more pronounced curbing role in the likelihood of stock price crashes for firms headquartered in areas with lower levels of social capital.

8 CONCLUSION

In this study, we investigate how federal judge ideology impacts firm-specific crash risk. We found that the degree of court liberalism is significantly and negatively associated with the likelihood of a firm experiencing future stock price crashes. The results are robust to alternative measurements of crash risk, judgment ideology, additional control variables and sample selection. The main findings remain consistent when we mitigate potential endogeneity concerns using matched samples. Regarding the potential mechanisms, we provide empirical evidence that liberal judge ideology negatively influences the likelihood of stock price crashes by reducing information opacity, constraining risk-taking behaviours and deterring overinvestment. Additionally, we find that the negative association between liberal judge ideology and crash risk is more salient for firms with weak internal monitoring and those located in regions with lower social capital.

Our study contributes to the understanding of judge ideology by examining its effects on extreme downside risks in the equity market. We provide evidence on how judicial appointments and political inclinations alter managerial behaviour, which further affects firm-specific crash risk. Additionally, we identify judge ideology as an important determinant of crash risk from the perspective of securities class action lawsuits. We also complement Obaydin et al. (2021) and emphasise the importance of distinguishing between primary types of legal recourse when discussing the impact of litigation threats.

This study also offers significant practical implications to managers, market participants and policymakers. First, our findings inform managers about the influence of federal judge ideology, facilitate their better understanding of the economic consequences of political appointments, and highlight the importance of considering judicial factors in decision-making process. Second, this study identifies federal judge ideology as a novel determinant that could be used to predict the likelihood of stock price crashes, which provides a beneficial reference for investors aiming to incorporate crash risk in their portfolios and risk management decisions. Finally, stock price crashes generally lead to huge losses in shareholder wealth and deteriorate capital market stability. Our results demonstrate that judges play a gatekeeping role in the capital market, which could also be of interest to policymakers when changing regulations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful for useful comments and suggestions they received from Xin Chen, Siwen Fu, Jinxing Qu, Yuyan Tang, Tracy Yeung, PhD seminars/workshop participants at City University of Hong Kong and Xian Jiatong University. The usual disclaimer applies. Open access publishing facilitated by Macquarie University, as part of the Wiley - Macquarie University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

APPENDIX 1: VARIABLE DEFINITIONS

| Variable | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Panel A: Dependent variables – Crash risk | |

| NCSKEW | The negative skewness of firm-specific weekly returns over the 12-month period ending 3 months after fiscal year-end |

| DUVOL | ‘Down’ weeks are the weeks with firm-specific weekly returns below the annual mean, while ‘up’ weeks are those with firm-specific returns above the annual mean. The variable DUVOL is the log of the ratio of the standard deviation on the down weeks to the standard deviation on the up weeks |

| Panel B: Independent variables – Judges' ideology | |

| LIB_COURT |

The probability that a three-judge panel randomly selected from a circuit court has at least two judges appointed by Democratic presidents, that is, [C (D, 3) + C (D, 2) × C (T − D, 1)]/C (T, 3) where T is the total number of judges in the circuit court, and D is the number of judges in the circuit court who are appointed by Democratic presidents. C (x, y) is the number of combinations of selecting y objects from x distinct objects. We exclude senior judges and first measure LIB_COURTm at the end of each month and then average it over a 12-month period consistent with the measurement window of crash risk variables to obtain an annual measure. We assign a value of LIB_COURT to each firm-year observation based on the location of the firm's headquarters by matching a circuit court-year with the firms' fiscal year |

| LIB_JUDGE | The number of judges appointed by Democratic presidents, scaled by total number of judges in a circuit court. We exclude senior judges and first measure LIB_JUDGEm (D/T) at the end of each month and then average it over a 12-month period consistent with the measurement window of crash risk variables to obtain an annual measure. We assign a value of LIB_JUDGE to each firm-year observation based on the location of the firm's headquarters by matching a circuit court-year with the firms' fiscal year |

| Panel C: Control variables | |

| DTURN | The average monthly share turnover over the current fiscal year period minus the average monthly share turnover over the previous fiscal year period, where monthly share turnover is calculated as the monthly trading volume divided by the total number of shares outstanding during the month |

| SIGMA | The standard deviation of firm-specific weekly returns over the fiscal year period |

| RET | The mean of firm-specific weekly returns over the fiscal year period, times 100 |

| SIZE | The log of the market value of equity |

| MB | The market value of equity divided by the book value of equity |

| LEV | The debt-to-assets ratio |

| ROA | Net income before extraordinary items and discontinued operations divided by lagged total assets |

| ACCM | The prior 3 years' moving sum of the absolute value of discretionary accruals, where discretionary accruals are estimated from the modified Jones model |

APPENDIX 2: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF LIB_COURT MEASURE

| Data year | Circuit court | Annual mean | Annual SD | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | D.C. | |||

| 2008 | 0.300 | 0.517 | 0.500 | 0.446 | 0.123 | 0.313 | 0.168 | 0.055 | 0.643 | 0.236 | 0.247 | 0.201 | 0.368 | 0.203 |

| 2009 | 0.303 | 0.406 | 0.511 | 0.514 | 0.130 | 0.243 | 0.190 | 0.055 | 0.639 | 0.262 | 0.294 | 0.226 | 0.366 | 0.197 |

| 2010 | 0.484 | 0.506 | 0.606 | 0.670 | 0.151 | 0.247 | 0.184 | 0.055 | 0.653 | 0.237 | 0.414 | 0.226 | 0.421 | 0.217 |

| 2011 | 0.442 | 0.637 | 0.574 | 0.706 | 0.225 | 0.278 | 0.183 | 0.055 | 0.695 | 0.331 | 0.506 | 0.256 | 0.460 | 0.219 |

| 2012 | 0.333 | 0.684 | 0.564 | 0.754 | 0.233 | 0.303 | 0.183 | 0.058 | 0.753 | 0.310 | 0.639 | 0.302 | 0.481 | 0.245 |

| 2013 | 0.647 | 0.685 | 0.623 | 0.753 | 0.221 | 0.263 | 0.183 | 0.138 | 0.751 | 0.473 | 0.684 | 0.536 | 0.520 | 0.238 |

| 2014 | 0.777 | 0.685 | 0.671 | 0.747 | 0.229 | 0.242 | 0.190 | 0.149 | 0.777 | 0.611 | 0.808 | 0.721 | 0.552 | 0.258 |

| 2015 | 0.800 | 0.685 | 0.662 | 0.758 | 0.242 | 0.242 | 0.225 | 0.074 | 0.776 | 0.636 | 0.848 | 0.721 | 0.555 | 0.266 |

| 2016 | 0.800 | 0.712 | 0.663 | 0.758 | 0.252 | 0.247 | 0.225 | 0.052 | 0.780 | 0.637 | 0.848 | 0.721 | 0.561 | 0.267 |

| 2017 | 0.800 | 0.721 | 0.694 | 0.773 | 0.277 | 0.231 | 0.140 | 0.050 | 0.828 | 0.710 | 0.782 | 0.753 | 0.568 | 0.285 |

| Circuit Mean | 0.561 | 0.619 | 0.603 | 0.685 | 0.207 | 0.262 | 0.188 | 0.074 | 0.724 | 0.444 | 0.591 | 0.439 | 0.481 | |

| Circuit SD | 0.207 | 0.105 | 0.065 | 0.109 | 0.051 | 0.028 | 0.024 | 0.036 | 0.063 | 0.178 | 0.218 | 0.228 | 0.251 | |

- Note: This appendix reports the descriptive statistics of LIB_COURT by circuit and year.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1 Huang et al. (2019) found that firms in liberal circuits are 35% more likely to be sued in securities class action lawsuits compared to those in conservative circuits, because liberal judges are more likely to vote in favour of investors.

- 2 The 12 circuits are geographically defined (see Figure 1), including 11 numbered circuits and the DC circuit.

- 3 Civil procedure usually requires securities class action lawsuits to be filed in the circuit where the firm's headquarters are located.

- 4 The decision of circuit court is regardless of whether this upholds or reverses the judgment of the district court. In most cases, circuit courts serve as the final arbiters (Choi & Pritchard, 2012).

- 5 There is also some concern about the ideology of lower courts. In fact, circuit court judges often overturn the decisions of the district court, such that district court judge rulings come to reflect the ideological preferences of the circuit court judges (Choi et al., 2012; Randazzo, 2008; Schanzenbach & Tiller, 2007).

- 6 The antifraud provisions of the federal securities law provide substance to the timely disclosure rules for stock exchanges. For example, Rule 10b-5 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 establishes liability for fraudulent practices in securities transactions. The scope of actionable conduct under this rule includes ‘(3) disclosure misrepresentation, either overtly or in certain circumstances in maintaining silence’.

- 7 The reason for starting the sample period in 2008 is that the Supreme Court's Tellabs decision essentially overturned the previous governing standings in the circuit courts, opening the door to greater latitude in judicial decision making (Huang et al., 2019). Specifically, subsequent to the Tellabs ruling, judges are allowed a higher degree of discretion in deciding whether to issue a motion to dismiss (Miller, 2009), which provides greater scope for them to shape case outcomes according to their ideology (Cox et al., 2009). For these reasons, we expect the effect of the ideology of federal judges on securities lawsuits to be more observable from the year 2008 onwards.

- 8 During the calculation process, we exclude senior judges, who have the option of taking a reduced caseload. In our robustness checks, we also construct alternative judge ideology measures with the senior judges included, and our main findings still hold.

- 9 In untabulated results, our main findings are consistent if we cluster standard errors by circuit.

- 10 In our sample, there are 21.31 judges in each circuit on average, including 8.89 liberal judges.

- 11 Specifically, we match high- and low-liberalism observations based on the closest propensity score and a maximum calliper distance of 0.001 (with replacement). Untabulated results indicate that all matching variables (except firm size) are statistically indistinguishable between the two groups.

- 12 The results in Table 6, Panels A–C, are not materially affected if LIB_JUDGE serves as the judge ideology measure (untabulated).

- 13 We estimate a firm-specific investment model according to Richardson (2006) and use the residuals as a firm-specific proxy for overinvestment.

- 14 The results in Table 7, Panels A and B, are not materially affected if LIB_JUDGE serves as the judge ideology measure (untabulated).