Does emotional intelligence matter to academic work performance? Evidence from business faculties in Australia

Abstract

Using data collected through survey questionnaire across 15 universities, we examine the effect of emotional intelligence on academic work performance (in research, teaching and service) in Australian business faculties. We find academics’ ability to use emotion enhances performance across research, teaching and service, while ability to regulate emotion enhances performance for teaching and service only. We also find support for a process-based model of emotional intelligence in which appraisal of emotion is a necessary antecedent to emotion’s use and regulation. The results have implications for management in appointment decisions and professional development programmes in business/accounting faculties.

1 Introduction

The purpose of this study is to examine the ability of academics’ emotional intelligence to affect their performance in research, teaching and service, in Australian business faculties. The study is motivated by major changes in the university environment and job demands for academics in recent years, and the need for research into the effect of the important individual-level factor of emotional intelligence on academic work performance.

The past two decades have witnessed seismic changes in the environment for universities world-wide. Globalisation and commercialisation of the higher education sector, accompanied by greatly reduced government funding and rapidly evolving technology, have placed pressure on universities to become more competitively aggressive, more accountable through formal quality assurance mechanisms and research performance metrics, and more business-like and market-driven (Steenkamp and Roberts, 2018; Vesty et al., 2018; Hancock et al., 2019).

These changes have resulted in equally seismic shifts in the job demands of academics, including heavier workloads, greater numbers of students with ‘customer-status’ expectations, burdensome administration, increasing pressure to publish, and the need to fulfil multiple, and potentially conflicting, job demands of research (including producing high-quality research outputs and raising funding through grants), teaching (including face-to-face and on-line teaching and teaching-related administration), and service (including service to the university and professional/practitioner communities and community engagement) (Modell, 2005; L’Huillier, 2012; Steenkamp and Roberts, 2018; Vesty et al., 2018).

While these changes to the academic work environment have been general across faculties, it has been argued that business and accounting faculties have been most strongly affected because business schools in general, and accounting faculties in particular, have been subject to the greatest pressures of over-enrolments and staff shortages leading to higher student/staff ratios and larger class sizes relative to other faculties (Pop-Vasileva et al., 2011; Su and Baird, 2017; Steenkamp and Roberts, 2018; Hancock et al., 2019). With respect to the accounting faculty, it has also been argued that the pressure to publish in top-tier accounting journals is more strongly felt than in other faculties because of the small number of such journals (Vesty et al., 2018).

There has been a number of studies in recent years of the adverse effects of these changes in the academic work environment on academics’ work-related attitudes and their psychosocial and physical health. Those studies have generally found increasing levels of job stress and burnout and decreasing levels of job satisfaction and organisational commitment (e.g., Pop-Vasileva et al., 2011; Su and Baird, 2017), as well as deleterious effects on wellbeing, work quality, and work-life balance (e.g., Bell et al., 2012; Steenkamp and Roberts, 2018).

Several studies have sought to identify managerial and organisational factors that may exacerbate or ameliorate these adverse effects. In their study of Australian academics in accounting and science faculties, Pop-Vasileva et al. (2011) found that differences in management style, level of organisational support, and design and use of performance management systems, were associated with job stress, satisfaction, and organisational commitment. Su and Baird (2017) found that collegiality positively affected commitment across their sample of Australian accounting academics, with the effects of collegiality flowing to reduced job-related stress and greater propensity to remain with the university.

Studies such as these are valuable in seeking to enhance the wellbeing and quality of work life for academics when confronted by the exigencies of the contemporary environment. However, there are two important omissions from the existing literature. The first is that the studies have focused mainly on attitudinal and psychosocial outcomes such as job stress, satisfaction, organisational commitment, wellbeing and work-life balance. By contrast, there has been virtually no research into the outcome of academic performance. Yet, as Bell et al. (2012, p. 25) argue, the effects of the many stressors on academics arising from their contemporary work environment extend beyond the psychosocial and the physical and on to the organisation itself, where academic performance at the individual level may result in poorer organisational performance and the ‘erosion’ of universities’ operating capabilities. Bell et al. (2012, p. 25) contend that ‘increasing levels of stress in university staff may be causing universities as institutions to not function as well as they might have in the past’. Martin-Sardesai et al. (2019) report some evidence of this, arguing that changes in the academic work environment, including to funding and performance measurement systems, have led to dysfunctional organisational outcomes of discouraging innovative research and gaming.

The second omission is that by contrast with studies that have focused on managerial and organisational factors that may affect outcomes in the academic work environment, no study has examined the individual-level factor of emotional intelligence. Yet, emotional intelligence (EI) has attained major status in the organisational behaviour, human resources and management (OBHRM) literatures in recent years as a significant predictor of work-related outcomes of job performance, leadership and conflict management (see Joseph and Newman, 2010; O’Boyle et al., 2011; Schlaerth et al., 2013; and Joseph et al., 2015 for meta-analytic studies of EI research in the OBHRM literatures). Lindebaum and Cartwright (2010) argue that EI is particularly important in (i) the knowledge work economy and (ii) changing and turbulent organisational environments. Consequently, one would expect EI to be an important predictor of academic work performance in the knowledge-based context of the higher education sector, and especially at a time when the sector is undergoing major environmental change.

The purpose of this study is to address these two omissions; that is, we examine the ability of academics’ level of EI to affect their work performance. First, we use the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) (Wong and Law, 2002), which comprises four dimensions of EI – self emotional appraisal, others’ emotional appraisal, regulation of emotion and use of emotion – to formulate and test hypotheses reflecting a process model of EI wherein the two appraisal dimensions are linked to the regulation and use dimensions in progressive sequence. We then contrast the three components of academic work performance – research, teaching and service – based on the extent to which they are higher or lower in emotional labour (defined as the extent to which the work entails extensive interpersonal interactions), to formulate and test hypotheses linking regulation and use of emotion to each of the three performance components.

Specifically, we hypothesise and find that self emotional appraisal and others’ emotional appraisal are antecedents to regulation of emotion and use of emotion in the process model, and that it is these latter dimensions that affect academic work performance. We also hypothesise and find that use of emotion affects all three components of academic work performance, while regulation of emotion affects performance in teaching and service, but not research.

Our paper contributes to the business/accounting education and EI literatures. First, we extend research linking EI and work performance to the university sector and to academic work. Most prior research has focused on jobs that are relatively homogeneous in task requirements, such as sales and nursing. By contrast, the task requirements for academic jobs are heterogeneous and multiple. The EI literature (e.g., Joseph and Newman, 2010; O’Boyle et al., 2011) has called for research into the importance of EI in jobs where individuals are required to perform across multiple tasks that differ in the degree of interpersonal interaction and, hence, emotional labour. Our study is the first to examine the role of EI in influencing academic performance across the three heterogeneous components of research, teaching and service.

Second, we disaggregate the four dimensions of EI. Many studies in the EI literature aggregate the dimensions and treat EI as unidimensional. However, recent EI research, such as Parke et al. (2015), Peña-Sarrionandia et al. (2015) and Pekaar et al. (2018), is moving towards more process-based approaches wherein the dimensions of EI are conceptualised as separate domains and examined both for their processual relations with each other (i.e., that self emotional appraisal and others’ emotional appraisal precede, and are linked to, regulation of emotion and use of emotion) and with job performance. This approach allows us to examine which of the four dimensions of EI affects which of the three components of academic work performance, and how those effects are structured in a process model.

2 Theory and hypotheses development

2.1 Emotional intelligence

Comprehensive discussion of EI research may be found in Law et al. (2004), O’Boyle et al. (2011), Joseph et al. (2015) and Siegling et al. (2015). Law et al. (2004) note that Salovey and Mayer (1990) were among the first to coin the term ‘emotional intelligence’. Salovey and Mayer (1990, p. 189) defined EI as ‘the subset of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions’. Van Rooy and Viswesvaran (2004, p. 72) defined EI similarly as ‘the set of abilities (verbal and non-verbal) that enables a person to generate, recognize, express, understand, and evaluate their own and others’ emotions in order to guide thinking and action that successfully cope with environmental demands and pressures’.

Based on Salovey and Mayer’s (1990) and Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) conceptualisation of EI, Wong and Law (2002) developed a four-dimensional model comprising self emotional appraisal, others’ emotional appraisal, regulation of emotion, and use of emotion. There are various dimensional models of EI in the social psychological literature, classified by Siegling et al. (2015) in their review as ability EI models (e.g., MacCann et al.’s (2011) Situational Test of Emotional Understanding), trait EI models (e.g., Schutte et al. (2009) Assessing Emotions Scale) and workplace-oriented EI models (e.g., Wong and Law’s (2002) Emotional Intelligence Scale). Wong and Law’s (2002) model was chosen for our analysis because it meets Siegling et al.’s (2015) criteria of its theoretical composition, psychometric properties, proven usefulness in both research and applied settings, and, as classified by Siegling et al. (2015), its focus on, and relevance to, the workplace. It has also consistently been used in EI research in workplace settings, including, for example, Sy et al. (2006), Trivellas et al. (2013) and Sony and Mekoth (2016). (For further theoretical and empirical evidence of the usefulness and applicability of the Wong and Law (2002) model, see Siegling et al., 2015, pp. 403–405).

Self emotional appraisal is ‘the individual’s ability to understand their deep emotions and be able to express these emotions naturally’. Others’ emotional appraisal relates to ‘peoples’ ability to perceive and understand the emotions of those people among them (and to be) much more sensitive to the feelings and emotions of others’. Regulation of emotion is ‘the ability of people to regulate their emotions, which will enable a more rapid recovery from psychological distress’. Use of emotion is ‘the ability of individuals to make use of their emotions by directing them towards constructive activities and personal performance’ (all quotations are from Wong and Law, 2002, p. 246).

Wong and Law’s (2002) four-dimensional model of EI is consistent with Gardner’s (1983) theory of multiple intelligences. Gardner (1983) proposed two intelligences, the intrapersonal and the interpersonal. Intrapersonal intelligence ‘involves the capacity to understand oneself, to have an effective working model of oneself – including one’s own desires, fears, and capacities – and to use such information effectively in regulating one’s own life’ (Gardner, 1999, p. 43). Interpersonal intelligence ‘denotes a person’s capacity to understand the intentions, motivations, and desires of other people and, consequently, to work effectively with others’ (Gardner, 1999, p. 43). Wong and Law (2002, pp. 247–248) contend that individuals who have a good understanding of the antecedents of their own and others’ emotions in social and work interactions, and who can respond to those emotions (i.e., individuals who are high in EI), ‘can make use of the antecedent- and response-focused emotional regulation effectively, and master their interactions with others in a more effective manner’.

2.2 The process-based approach to EI

Much prior EI research that has used Wong and Law’s (2002) four-dimensional model of EI (or other dimensional models such as Schutte et al.’s (1998) Assessing Emotions Scale), has either aggregated the dimensions in analysis (e.g., Van Rooy et al., 2005; Sy et al., 2006; Weinzimmer et al., 2017) or, in a few cases, has sought to relate each of the four dimensions directly to job performance or other related outcomes (e.g., Trivellas et al., 2013; Sony and Mekoth, 2016). By contrast, recent research has begun to move towards a process-based approach wherein the dimensions of EI are conceptualised as separate domains and examined both for their processual relations with each other and with job performance and other outcomes. This approach stems from Wong and Law’s (2002) original conceptualisation of the four dimensions of EI, and from Joseph and Newman’s (2010) ‘cascading model’ of EI.

Wong and Law (2002, p. 247) argue that people need to have a good understanding of emotions before they can regulate or use emotions. That is, appraisal (both self emotional appraisal and others’ emotional appraisal) must precede regulation and use of emotion. In a similar vein, Joseph and Newman (2010) and Pekaar et al. (2018) argue that the perception and understanding of emotion must precede emotion regulation which, in turn, must precede job performance. Joseph and Newman (2010) contend that this progressive sequence is theoretically causal as the reverse, i.e., that regulation (or use) of emotion precedes perception and understanding of emotion, cannot be true. Pekaar et al. (2018, p. 139) argue that ‘the appraisal of emotion seems a prerequisite for more complex emotion-related processes such as the regulation of emotion’, and that this ‘highest and most complex level of emotion processing, emotion regulation, is the ultimate step through which external criteria such as job performance are affected’.

The process-based approach argues that the appraisal dimensions of EI do not directly affect job performance. While self emotional appraisal and others’ emotional appraisal are important in the acquisition of information about the emotions of self and others, they are unlikely to have effects on job performance unless the information acquired is put to use; i.e., either to regulate one’s emotions in interpersonal interactions in the workplace or to motivate emotional engagement with the task to be performed. The lack of a direct relation between the appraisal dimensions and job performance is supported empirically by Joseph and Newman (2010) and Pekaar et al. (2018).

The process-based approach also rests on the theoretical premise that regulation and use of emotion must precede performance. This premise is explicit in Joseph and Newman’s (2010) ‘cascading model’ of EI that not only identifies the theoretically causal linkages between the appraisal/perceptual dimensions and the regulation and use dimensions, but also extends that theoretical causality to link the regulation and use dimensions to job performance. The premise that EI is a predictor of, and causal influence on, job performance and a range of individually- and organisationally valued outcomes underpins all the studies of EI reviewed in the meta-analytical papers (e.g., Joseph and Newman, 2010; O’Boyle et al., 2011; Schlaerth et al., 2013; Joseph et al., 2015).

H1a: Self emotional appraisal is associated with regulation of emotion and use of emotion.

H1b: Others’ emotional appraisal is associated with regulation of emotion and use of emotion.

2.3 Hypothesis 2: Regulation of emotion and academic work performance

Our second hypothesis is that regulation of emotion links to two components of academic work performance – teaching and service – but not research. Regulation of emotion reflects the ability of high EI individuals to manage their emotions in potentially difficult and conflictual interpersonal interactions with others; it allows those individuals ‘to master their interactions with others in a more effective manner’ (Wong and Law, 2002, pp. 247–248). It is particularly important when the work is high in emotional labour; that is, when the work entails extensive interpersonal interactions with others, where others may be clients, co-workers in team-oriented tasks, or members of professional, practitioner or societal communities (Wong and Law, 2002; O’Boyle et al., 2011).

Academic work comprises multiple different components with varying requirements on the individual academic. One of the differences is that teaching and service are high in emotional labour, whereas research is low, or at least, less high. Teaching and service both involve the individual academic in intensive and extensive interaction with others, specifically with students, with faculty and university colleagues, and/or with representatives of professional and practitioner communities or other societal constituents. As such, these components of the academic job are high in emotional labour, requiring the individual to be sensitive to, and empathetic with, those others in order to facilitate effective communication and working relationships, and, hence, superior job performance (Lindebaum and Cartwright, 2010; Campo et al., 2015; Sony and Mekoth, 2016).

Additionally, O’Boyle et al. (2011, pp. 793–794) note that emotional labour is high when ‘employees must alter their emotional expressions in order to meet the display rules of the organization’. This reflects the teaching and service components of the academic job because individual academics are representatives of their institutions in their interactions with others, and must uphold their institutions’ precepts and values in those interactions.

O’Boyle et al. (2011, p. 794) also contend that emotional labour may be particularly stressful for employees who may lack autonomy in their job, and that it is in this situation that the ability to regulate one’s emotions may be particularly beneficial to the reduction of stress and to better performance outcomes. Arguably, academics, particularly in the business and accounting faculties, have less autonomy over the content of their course curricula and the delivery and assessment of that content contemporarily, because of greater centralisation, standardisation, and control of content and delivery mode occasioned by the need to comply with the requirements of external accreditation bodies such as the AACSB (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business) and, for accounting faculties, the professional accounting bodies in Australia.

H2: Regulation of emotion is associated with teaching and service performance.

2.4 Hypothesis 3: Use of emotion and academic work performance

Our third hypothesis is that use of emotion links to all three components of academic work performance. Use of emotion is described by Wong and Law (2002, p. 246) as ‘the ability of individuals to make use of their emotions by directing them towards constructive activities and personal performance’.

Parke et al. (2015, p. 921) draw on affective information processing theory (Gohm and Clore, 2000) to argue that better thinking and decision-making result from the ability of individuals to use their emotions to direct attention and effort to the task, to identify emotions and feelings experienced during task decision-making, and to recognise the appropriate emotional states required for specific tasks. Parke et al. (2015) examined the effect of use of emotion on employees’ creativity. They noted that the two key mechanisms underpinning creativity performance are cognitive flexibility and motivation, with the latter serving to affect both the employee’s propensity to take on the challenge of the task, and the ‘psychological engagement’ to sustain effort directed to the task (Parke et al., 2015, p. 921). Similarly, Joseph et al. (2015) argue for a link between EI and accomplishment striving and goal setting. Combining Parke et al. (2015) and Joseph et al. (2015), we hypothesise that people who are high on the use of emotion dimension of EI will have higher levels of performance because of their ability to use their emotions to sustain motivation, accomplishment striving and goal setting.

H3: Use of emotion is associated with teaching, service and research performance.

3 Method

Data were collected by mail survey questionnaire sent to 1,205 academics in the disciplinary areas of accounting, finance, economics, management and marketing in business faculties at 15 Australian universities. Three universities were chosen at random from each of Moodie’s (2002) five categories: G8, Australian Technology Network, 1960–70s, New Generation and Regional. All full-time academics at all levels were included. Part-time/adjunct staff and staff with teaching-only or research-only responsibilities were excluded. The academics and their contact details were obtained from official university websites, and all questionnaires were mailed to their university addresses.

Hard copy questionnaires were used rather than online administration of the survey because hard copy has consistently been found to yield higher response rates, protect respondents’ anonymity and improve data quality compared to web-based surveys (Dillman et al., 2009; Lin and Van Ryzin, 2012). Survey design and administration were conducted in accordance with Dillman et al.’s (2009) Tailored Design Method. After one follow-up, by hard copy mail, 376 questionnaires were received for a response rate of 31.2 percent. This compares favourably with other recent surveys of Australian academics which have generated 15.6 percent (Hancock et al., 2019), 20.4 percent (Vesty et al., 2018) and 33 percent (Su and Baird, 2017). Interest in the survey was high, evidenced by 184 respondents requesting a summary of the findings.

3.1 Variable measurement

Emotional intelligence (EI) was measured using Wong and Law’s (2002) Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS). The WLEIS has consistently been found to have good psychometric properties (Lindebaum and Cartwright, 2010; Trivellas et al., 2013; Siegling et al., 2015; Sony and Mekoth, 2016). As shown in Table 1, the WLEIS is a 16-item scale comprising four dimensions of self emotional appraisal, others’ emotional appraisal, regulation of emotion and use of emotion. Respondents were requested to state the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each item/statement on a 7-point Likert-type scale, with anchors of ‘1 = Strongly disagree’ and ‘7 = Strongly agree’. Scores for each of the four dimensions were summed with higher (lower) scores indicating higher (lower) levels of each dimension.

| Construct and measurement items | Cronbach's α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self emotional appraisal | 0.899 | 0.930 | 0.770 |

| I have a good sense of why I have certain feelings most of the time | |||

| I have a good understanding of my own emotions | |||

| I really understand what I feel | |||

| I always know whether I am happy or not | |||

| Others’ emotional appraisal | 0.893 | 0.926 | 0.758 |

| I always know my friends’ emotions from their behaviour | |||

| I am a good observer of others’ emotions | |||

| I am sensitive to the feelings and emotions of others | |||

| I have good understanding of the emotions of people around me | |||

| Regulation of emotion | 0.901 | 0.931 | 0.772 |

| I am able to control my temper and handle difficulties rationally | |||

| I am quite capable of controlling my own emotions | |||

| I can always calm down quickly when I am very angry | |||

| I have good control of my own emotions | |||

| Use of emotion | 0.805 | 0.872 | 0.631 |

| I always set goals for myself and then try my best to achieve them | |||

| I always tell myself I am a competent person | |||

| I am a self-motivated person | |||

| I would always encourage myself to try my best | |||

| Research performance | 0.804 | 0.873 | 0.637 |

| Number of refereed publications | |||

| Quality of journals for publications | |||

| Research grants | |||

| Research student supervision | |||

| Teaching performance | 0.767 | 0.853 | 0.594 |

| Student evaluation ratings | |||

| Peer feedback | |||

| Innovation in teaching | |||

| Improvement in teaching-related programmes | |||

| Service performance | 0.753 | 0.840 | 0.571 |

| Service to the department/school/faculty/university | |||

| Service to the academic community | |||

| Service to the professional/business community | |||

| Service to the local community |

Our measure of academic work performance was based on, first, Su and Baird (2017), who developed the measure by identifying from the literature the commonly used criteria for evaluating academics’ work performance. Su and Baird (2017) made the first attempt to develop an academic work performance measure in the university setting. As expected, their measure produced three dimensions of performance: research performance (four items), teaching performance (three items) and service performance (two items), for which high Cronbach’s alpha scores were reported. To enhance the measure for our study, we further reviewed the literature on performance measurement systems (PMS) in Australian universities, which provided additional insight into university performance criteria for academics (e.g., Pop-Vasileva et al., 2011; Parker, 2012; Guthrie and Parker, 2014; Guthrie et al., 2015; Martin-Sardesai et al., 2017). As shown in Table 1, we used a total of 12 items to measure performance across research (four items comprising quantity and quality of publications, grants and research supervision), teaching (four items comprising student and peer evaluation, and teaching innovation and improvement) and service (four items reflecting service to the university and to the academic, professional/business and local communities). To ensure that our measure is generally applicable to Australian business schools, we discussed and confirmed the measure (and its component parts) with two scholars who specialise in research on PMS in Australian business schools.

Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they had met their department’s/school’s performance expectations for each item in the past 12 months on a 7-point, Likert-type scale with anchors of ‘1 = Not at all’ and ‘7 = To a great extent’. Scores for each of the dimensions were summed with higher (lower) scores indicating higher (lower) levels of performance. We recognised that not all performance items would apply to all individual academics (e.g., early career academics might not have undertaken research student supervision). Hence, we also provided an ‘NA’ (not applicable) option for each performance item.

Table 1 shows that all the focal variables have good psychometric properties of reliability and validity. The calculated Cronbach’s α, CR and AVE are all above the accepted thresholds of 0.7, 0.8 and 0.5, respectively.

Five variables were included as controls: age, gender, working hours, academic level (position) and years of experience. Each may be generally considered to affect academic performance. Age, gender and academic position were categorical, with age classified into six 10-year bands from ‘20 to 29’ to ‘70 or above’ (coded 1 to 6), gender coded 0 for female and 1 for male, and academic level into five levels of A (Associate Lecturer/Tutor) to E (Professor) (coded 1 to 5). Respondents were also asked the average number of hours they worked each week (working hours) and their approximate number of years of academic experience (years of experience). Logarithmic transformation was used for both variables.

3.2 Biases

Survey research is potentially subject to biases of non-response and, where respondents provide self-report measures of both the independent and dependent variables, common method. Self-report measures were necessary in our survey because (i) given the need for anonymity, obtaining independent or corroborating data from other sources was impossible, and (ii) no objective data are available for the teaching and service components of academic performance.

With respect to non-response bias, we split the data into two sub-samples of early versus late respondents, proxying late respondents for non-respondents. This is a widely accepted procedure for testing non-response bias in social science/business research (e.g., Pop-Vasileva et al., 2011; Bui et al., 2017; Gong and Subramaniam, 2018). t-Tests comparing the sub-samples for levels of each of the EI dimensions, each of the three components of academic performance, and the demographic control variables, showed no statistically significant differences between the early and late respondents for any of the variables.

Whether common method bias is a problem when dealing with self-reported, perceptual data is the subject of disagreement among social science researchers, with Podsakoff et al. (2012) citing several methodological studies (e.g., Spector, 1987, 2006 and Spector and Brannick, 2009) that conclude the problem is overstated or non-existent (also see Crampton and Wagner, 1994). Nonetheless, we conducted two ex post tests commonly used to test whether common method bias might be present: Harman’s (1967) single-factor test, which has been widely used in this context (e.g., Linnenluecke et al., 2015; Bui et al., 2017; Gong and Subramaniam, 2018; Xue et al., 2019), and Kock’s (2015) full collinearity test using structural equation modelling. Both tests indicate that common method bias is unlikely to be a concern in our sample.

4 Results

Respondents were spread across the university categories at 21.4, 27.3, 22.0, 15.2, and 14.1 percent, for G8, Australian Technology Network, 1960–70s, New Generation, and Regional, respectively. Of the respondents, 57.8 percent were male. Level B (Lecturer) and Level C (Senior Lecturer) academics made up a large proportion of the respondents at 32.0 and 30.5 percent, respectively, followed by Level D (Associate Professor, 17.9 percent) and Level E (Professor, 14.1 percent).

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics, correlation matrix and discriminant validity. The lack of any high correlations among the independent variables suggests multicollinearity is unlikely to be a problem. Discriminant validity is supported, as the square roots of the average variance extracted (shown on the diagonal) are significantly larger than the correlations.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEA | 5.64 | 0.98 | |||||||||||

| OEA | 4.89 | 1.07 | 0.43*** | 0.871 | |||||||||

| ROE | 5.58 | 0.95 | 0.48*** | 0.31*** | 0.879 | ||||||||

| UOE | 5.16 | 1.13 | 0.44*** | 0.29*** | 0.29*** | 0.794 | |||||||

| Research performance | 4.51 | 1.53 | 0.11* | 0.05 | 0.21*** | 0.11+ | 0.798 | ||||||

| Teaching performance | 5.41 | 0.99 | 0.26*** | 0.16** | 0.27*** | 0.28*** | 0.19*** | 0.771 | |||||

| Service performance | 5.10 | 1.14 | 0.19*** | 0.20*** | 0.24*** | 0.22*** | 0.29*** | 0.49*** | 0.755 | ||||

| Age | 3.40 | 1.09 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.25*** | −0.08 | 0.00 | ||||

| Gender | 0.58 | 0.49 | −0.07 | −0.21*** | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.10+ | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.06 | |||

| Hours | 3.85 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.12* | 0.12* | 0.03 | ||

| Position | 3.09 | 1.16 | −0.03 | −0.10+ | 0.04 | −0.10+ | 0.31*** | −0.04 | 0.18** | 0.33*** | 0.20*** | 0.17** | |

| Years | 2.38 | 0.82 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.13* | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.61*** | 0.04 | 0.18*** | 0.39*** |

- The square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) are shown as bold figures on the diagonal and correlations are shown off-diagonal. Supporting discriminant validity among the key constructs, the square roots of AVE (on the diagonal) are significantly larger than the correlations (reported off-diagonal). SEA, self emotional appraisal; OEA, others’ emotional appraisal; ROE, regulation of emotion; UOE, use of emotion. Coding for gender: 0 = female and 1 = male. Significance levels (two-tailed): +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

4.1 Main analysis

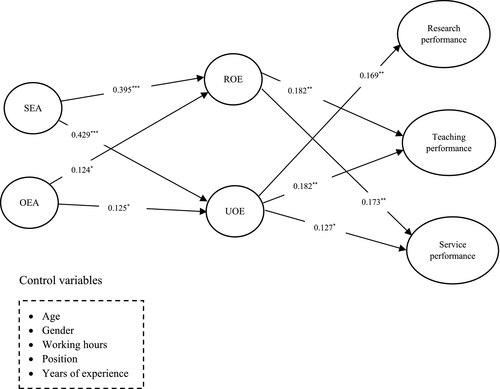

The hypotheses were tested using structural equation modelling (SEM). The structural model is depicted in Figure 1 for the focal variables, with regulation of emotion and use of emotion intermediating self emotional appraisal and others’ emotional appraisal and the response variables of research, teaching and service performance. The control variables were also included in the structural model. Using the partial least squares method, the path coefficients were estimated, and their p-values were obtained based on 5,000 bootstrapping runs (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Figure 1 shows the coefficients and p-values for the significant paths, and Table 3 shows the path coefficients and associated p-values for all paths.

| Coefficient | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Self emotional appraisal | ||

| SEA → ROE | 0.395 | 0.000*** |

| SEA → UOE | 0.429 | 0.000*** |

| SEA → Research performance | 0.027 | 0.655 |

| SEA → Service performance | 0.004 | 0.949 |

| SEA → Teaching performance | 0.098 | 0.119 |

| Others’ emotional appraisal | ||

| OEA → ROE | 0.124 | 0.047* |

| OEA → UOE | 0.125 | 0.030* |

| OEA → Research performance | −0.022 | 0.670 |

| OEA → Teaching performance | −0.002 | 0.970 |

| OEA → Service performance | 0.104 | 0.112 |

| Regulation of emotion | ||

| ROE → Research performance | 0.087 | 0.119 |

| ROE → Teaching performance | 0.182 | 0.001** |

| ROE → Service performance | 0.173 | 0.001** |

| Use of emotion | ||

| UOE → Research performance | 0.169 | 0.002** |

| UOE → Teaching performance | 0.182 | 0.001** |

| UOE → Service performance | 0.127 | 0.020* |

| Control variables | ||

| Age → Research performance | −0.359 | 0.000*** |

| Age → Teaching performance | −0.106 | 0.168 |

| Age → Service performance | −0.015 | 0.806 |

| Gender → Research performance | 0.049 | 0.322 |

| Gender → Teaching performance | −0.014 | 0.793 |

| Gender → Service performance | −0.089 | 0.085+ |

| Hours → Research performance | 0.029 | 0.487 |

| Hours → Teaching performance | 0.036 | 0.481 |

| Hours → Service performance | 0.106 | 0.016* |

| Position → Research performance | 0.443 | 0.000*** |

| Position → Teaching performance | −0.011 | 0.837 |

| Position → Service performance | 0.299 | 0.000*** |

| Years → Research performance | −0.075 | 0.224 |

| Years → Teaching performance | 0.033 | 0.699 |

| Years → Service performance | −0.143 | 0.019* |

- SEA, self emotional appraisal; OEA, others’ emotional appraisal; ROE, regulation of emotion; UOE, use of emotion. Coding for gender: 0 = female and 1 = male. Significance levels (two-tailed): +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Supporting H1a, Figure 1 and Table 3 show that self emotional appraisal was positively associated with both regulation of emotion (β = 0.395, p < 0.001) and use of emotion (β = 0.429, p < 0.001). H1b was also supported, in that others’ emotional appraisal was positively associated with both regulation of emotion (β = 0.124, p < 0.05) and use of emotion (β = 0.125, p < 0.05). Supporting H2, regulation of emotion was positively associated with teaching performance (β = 0.182, p < 0.01) and service performance (β = 0.173, p < 0.01). Supporting H3, the results showed that use of emotion was positively associated with all three dimensions of academic performance: research (β = 0.169, p < 0.01), teaching (β = 0.182, p < 0.01) and service (β = 0.127, p < 0.05).

With respect to the main dimensions of academic performance, research and teaching, no significant influences were found for gender, working hours or years of experience. Age was negatively associated with research performance (β = −0.359, p < 0.001), perhaps because research is less (more) important to career establishment and progression for older (younger) academics, or because life commitments increase with age, decreasing the time available for research. Position was positively associated with research performance (β = 0.443, p < 0.001) and service performance (β = 0.299, p < 0.001), suggesting perhaps that the higher the position, the more resources and connections are available to support research activities, and the more opportunities are available for grant applications, research student supervision, and service contributions at higher levels of the university, academic and professional/business communities.

The associations for age and research performance, and position and both research and service performance, are based on linear analysis. As suggested by a reviewer, we examined these associations more closely given that older academics are likely to hold more senior positions. Further analysis showed a curvilinear association; i.e., within each position, younger (older) academics were observed to have higher (lower) mean performance. The association appears to be concave-down; that is, performance increases with age in the lower range (across all positions) but decreases in the higher range. Although it is beyond the scope of the present study, further examination of these intra-positional, intra-age associations is warranted.

Although they are control variables in our study, we were encouraged by a reviewer to examine further the links between the EI dimensions (of regulation of emotion and use of emotion) and the three components of academic performance (research, teaching and service) for males and females and less senior (Levels A, B and C) and more senior (Levels D and E) academics. The multiple comparisons produced by these analyses are not tabulated here. In sum, they show, firstly, that there are many similarities across the sub-samples and the performance components. That is, our results in the main analysis for the pooled sample apply to males and females, and less senior and more senior academics. The results of the sub-analyses also show that the effect of the EI dimensions on performance outcomes for more senior academics is stronger than for less senior ones, and this effect, in turn, is stronger for the EI dimension of regulation of emotion compared to use of emotion.

4.2 Additional analysis

This additional analysis was prompted by the insightful comments of a reviewer who suggested that, because academics vary in their abilities to perform across the components of research, teaching and service, it would be informative to examine whether the EI dimensions influence academics’ breadth of performance. To examine this (i.e., do differences in the EI dimensions affect whether academics perform ‘broadly’ across the components or ‘narrowly’), we constructed a measure of performance breadth by (i) assigning a score of 1 (0, otherwise) to a given performance component if the self-reported performance rating for that component was above the mean for all responses for that component, and (ii) summing the scores for a given academic across the three components. The resulting score is a measure of whether the academic is a ‘narrow’ or ‘broad’ performer. If the score is 1, this indicates ‘narrow’ performance as the self-rated performance is high on one component only. If the score is greater than 1, with a maximum of 3, this indicates ‘broader’ performance as the self-rated performance is high on more than one component.

Using this constructed measure, we re-estimated the SEM model by relating self emotional appraisal and others’ emotional appraisal to regulation of emotion and use of emotion, and then relating regulation of emotion and use of emotion to the new performance breadth measure. The results, shown in Table 4, suggest that (i) the first set of relations (i.e., between the two emotional appraisal dimensions and regulation and use of emotion) are essentially unaffected by the use of the new measure, and (ii) regulation of emotion and use of emotion significantly influence performance breadth. That is, academics who are higher on the regulation and use of emotion dimensions of EI perform more broadly across the components of academic performance compared to those who are low on these dimensions.

| Path | Path coefficient | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| SEA → ROE | 0.396 | 0.000*** |

| SEA → UOE | 0.428 | 0.000*** |

| OEA → ROE | 0.123 | 0.020* |

| OEA → UOE | 0.127 | 0.040* |

| ROE → Performance breadth | 0.211 | 0.000*** |

| UOE → Performance breadth | 0.277 | 0.000*** |

| Age → Performance breadth | −0.129 | 0.031* |

| Gender → Performance breadth | −0.001 | 0.988 |

| Hours → Performance breadth | 0.115 | 0.020* |

| Years → Performance breadth | −0.093 | 0.107 |

| Position → Performance breadth | 0.184 | 0.000*** |

- SEA, self emotional appraisal; OEA, others’ emotional appraisal; ROE, regulation of emotion; UOE, use of emotion. Coding for gender: 0 = female and 1 = male. Significance levels (two-tailed): *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Combining the results of this additional analysis with the results reported in the main analysis, we find that regulation of emotion and use of emotion not only positively influence the individual performance dimensions of research, teaching and service, but also positively influence whether an academic performs broadly or narrowly across the key performance metrics required by universities in Australia. This additional finding further highlights the utility of developing emotion-related competences to attain superior performance outcomes.

5 Conclusions, implications and limitations

Motivated by the importance of examining factors which may ameliorate the adverse effects on academics and academic work performance arising from the increasingly stressful and demanding work environment of the 21st century, this study examined the effect of emotional intelligence (EI) on the performance of academics in business faculties in Australia across the three performance components of research, teaching and service.

While EI has been proposed and found to affect work performance in jobs generally, it has not been previously examined in the academic job context; a context which differs from many other job situations because it comprises multiple components with differing degrees of emotional labour. The demands of academic work are multiple and heterogeneous, ranging across research, teaching and service. These work demands differ in the extent to which they require emotional labour; i.e., the extent to which they involve interpersonal relations and interactions with others. Specifically, teaching and service are high in emotional labour because they involve extensive and intensive interaction with students, other faculty and representatives of the professional, practitioner and general communities. Research is low, or less high, in emotional labour because it is typically conducted (in the business discipline, particularly) in small teams of colleagues who are usually well known to each other.

Using Wong and Law’s (2002) four-dimensional Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS), we found firstly that the two dimensions relating to the appraisal of emotion (self emotional appraisal and others’ emotional appraisal) were linked in progressive sequence to the regulation of emotion and use of emotion. Secondly, we found that while use of emotion was associated with performance for all three components of the academic job, regulation of emotion was associated only with performance for the teaching and service components. Thirdly, from our additional analysis, we found that regulation of emotion and use of emotion were associated with performance breadth, that is, performance across the three academic job components combined. We also found that the effects of regulation of emotion and use of emotion on academic work performance were generally similar across gender and position, but that those effects were stronger for more senior relative to less senior academics. As expected, we found no direct association between the appraisal dimensions and performance for any of the three components, meaning that while the ability to appraise (perceive or understand) emotions is a critical antecedent of the ability to regulate and use emotions, it is the latter two dimensions that are important in affecting performance.

Our findings have implications for both the EI and higher education research literatures, as well as for management practice in universities. With respect to the EI literature, a major implication arises from the finding that use of emotion affects all three components of academic work performance, whereas regulation of emotion affects the teaching and service components only. Most prior EI research has been predicated on the assumption that both use and regulation of emotion would be represented similarly in the effect of EI on performance. Disaggregating both the dimensions of EI and the components of performance, here academic performance, has allowed us to demonstrate that the effects of use of emotion and regulation of emotion may be represented differentially in their effects on performance.

Also, as noted earlier, many EI studies that have used a dimensional approach have either aggregated the dimensions or have sought to relate each of the dimensions directly to job performance or other outcomes. The reasons given for aggregation are that the researcher may be interested in EI as an overall construct or, as argued by Weinzimmer et al. (2017), because there is debate about the multidimensionality and factor structure of the dimensional EI construct. By contrast, our study provides support for the process-based approach to the EI construct and for its use in future studies.

Our study also has implications for research and management practice in universities. First, we have demonstrated the importance of EI in affecting academics’ work performance. We theorised and found that academics who are better able to use their emotions in the work setting performed better across all three components of academic performance than those with lower levels, while those who are better able to regulate their emotions performed better across the teaching and service components, but not the research component.

These findings have implications for future research into factors affecting academics working in the increasingly stressful and demanding work environment of the 21st century. We believe ours to be the first study to examine EI in this context and, given the significant results, future research may wish, or need, to include EI as an individual-level factor additional to, or combined with, organisational-level factors in affecting other work-related attitudes of academics, such as job satisfaction and organisational commitment, as well as psychosocial outcomes such as wellbeing and work-life balance/conflict.

With respect to management practice in universities, our findings have implications for appointment decisions and for professional development programmes for academics. EI is a dynamic construct, and can be developed and enhanced in-house through interventions. While it is beyond the scope of this study to detail such interventions, Pool and Qualter (2012) and Campo et al. (2015) discuss a variety of interventions ranging from on-going, informal approaches such as coaching and role modelling, to formal training programmes involving, inter alia, lectures, case studies, experiential learning, role-playing, and other techniques designed to develop and/or enhance the recognition, regulation and use of emotion. Campo et al. (2015) review studies that have implemented various formal intervention techniques in a variety of contexts, including real-world and experimentally controlled contexts, and provide evidence of the ability of those interventions to produce sustainable enhancement in EI.

Universities do not typically engage in psychometric testing at appointment. While it may be assumed that cognitive ability is not hugely variable across academics as most have a history of high academic performance in their undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, and a relatively uniform developmental structure in their academic careers, no such assumption can be made about EI. And while cognitive ability might have been sufficient to determine academic success in the more benign environment of higher education prior to globalisation and commercialisation, it is less likely to be sufficient in the contemporary environment, characterised by high levels of emotional labour in academic work overall, and where EI is increasingly important. Hence, universities might well seek to include in their suite of academic staff development processes and programmes, ones which are directed to the development and/or enhancement of EI.

Alternatively, in the absence of EI interventions, universities may use EI assessments in work allocation decisions. While the typical academic workload comprises research, teaching and service, there are variations with some institutions utilising research-only or research-intensive positions and/or teaching-only/intensive positions. In allocating such positions, university managers may need to take account that performance in teaching is enhanced when the individual academic possesses both regulation and use of emotion, while performance in research is less dependent on the ability to regulate emotion. University managers may, therefore, seek to ensure that academics in heavy teaching roles are high in the ability to both regulate and use their emotion. Similarly, given the contemporary importance of universities engaging with a broad constituency of stakeholders and the media, universities should ensure that individuals placed in those important engagement roles are also high in both regulation and use of emotion.

Finally, our finding that the effects of regulation of emotion and use of emotion were stronger for more senior academics highlights the importance of ensuring or enhancing the EI of senior academics generally. This is because these academics typically occupy senior and leadership positions. Specifically, more emphasis should be placed on regulation of emotion, as it is important for senior academics to control emotions in conducting work high in emotional labour. This is especially the case when senior academics need to manage situations of interpersonal conflict and group dynamics in the academic work environment.

Our study has several limitations. One is that we used a multi-dimensional measure for academic work performance, built on Su and Baird (2017) and supported by additional literature review, reflecting academics’ work demands in the three components of research, teaching and service. However, as helpfully suggested by a reviewer of the paper, future research may seek to further elaborate on this measure by examining how specific facets within each component are assessed. For example, with respect to teaching performance, future research may drill down to examine how facets such as peer feedback and teaching innovation are assessed.

A second limitation is that we restricted our study to academics in business faculties. There is some evidence that work-related attitudes of academics in business faculties may differ from those in other faculties (Pop-Vasileva et al., 2011). However, those differences, if they do exist, relate to the mean levels of work-related attitudes and outcomes. There appears no reason why the effect of EI on those attitudes and outcomes would not be generalisable across faculties. Nonetheless, future research may extend our study both into different work-related attitudes and outcomes and across different faculties.