Does prestigious board membership matter? Evidence from New Zealand

Abstract

This study investigates whether ‘prestigious’ multiple board membership is positively associated with firm performance. We employ Resource Dependency theory to explain why performance outcomes may be improved by the presence of ‘prestigious’ multiple directorships. Our analysis relies on extensive hand-collected data on New Zealand company directorships. The results support the contention that ‘prestigious’ multiple directorships are related to better accounting and market performance. Conclusions reflect upon how Resource Dependency theory informs this phenomenon and how ‘prestigious’ board members may be a valuable resource for firms. We also reveal how these findings expose a new avenue for board governance research.

1 Introduction

The presence of multiple directors on corporate boards and their influence in business is of growing interest in the literature. Directors who sit on more than one board are exposed to a variety of organisational practices. As a result, they may contribute unique skills and experiences to the boards with which they are associated. Compared to the single director, directors with multiple board memberships serve their firms from a greater array of business understandings, connections, and knowledge of industry practices (Kirkpatrick, 2009; Withers et al., 2012).

Much of the research into multiple directorships (MDS) concerns itself with ‘how’ busy multiple directors may be (Ferris et al., 2003; Fich and Shivdasani, 2006; Jiraporn et al., 2009; Field et al., 2013; Lei and Deng, 2014; Rouyer, 2016; Huebner, 2018; Kress, 2018; Mans-Kemp et al., 2018). The argument is that multiple directors may be less effective governing board members because they are overly-occupied with their other board obligations (Adams et al., 2010). Such concerns are also raised in New Zealand and Australian studies (e.g. Laurent, 1971; Firth, 1987; Alexander et al., 1994; Fox and Hamilton, 1994; Fox and Walker, 2001).

With existing studies that examine board busyness and offer mixed (and at times inconsistent) findings into MDS, we address the question if there are attributes of MDS which could either offset ‘busyness’ costs or otherwise offer a way forward in suggesting how MDS can also contribute to a firm’s success.

One such attribute is the ‘prestige’ of board members: some board members with multiple directorships may bring more value to their boards than others (Gupta et al., 2008; Kim and Cannella, 2008; Eminet and Guedri, 2010; Cashman et al., 2013). Though intuitively appealing, no investigation has yet directly tested whether ‘prestigious’ multiple directors positively affect firm performance.

To examine whether firm performance outcomes are improved by the presence, or absence, of ‘prestigious’ multiple directorships, this study draws upon resource dependency theory. Using hand-collected New Zealand data, we thus test whether ‘prestigious’ multiple directorships constitute an important resource for New Zealand firms.

Our results demonstrate that firms with more ‘prestigious’ directors are positively associated with firm performance, while there is a negative or insignificant relationship between non-prestigious MDS and firm performance. The results are robust with respect to short- and long-term firm performance, time period, alternative measures of firm performance and endogeneity.

We contribute to the literature on boards and governance by showing that prestigious multiple directorships matter for firms. This is particularly relevant in the context of New Zealand, where the pool of directors is limited. We also contribute by introducing a new avenue of research into corporate governance. While the literature has focused on the implications of MDS by considering individual directorships, their ‘busyness’ or their interlocking nature, there is little knowledge about distinctions that may ensue from different types of multiple directorships. Lastly, we contribute to the literature by using a rich set of contemporaneous data, which adds to the relevance of this study.

2 Theoretical development

This study draws on resource dependency theory (RDT) to inform the hypotheses and to evaluate the results. Resource dependency ‘conceptualizes the environment in terms of other organizations with which the focal organization engages in exchange relationships’ (Banaszak-Holl et al., 1996, p. 99). RDT views business as an open system, operating within its larger economic and social environment (e.g. Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978). It asserts that managers seek to exert control over this larger environment so as to reduce uncertainty and dependence on others (Hillman et al., 2009). Thus, managers may form symbiotic and collaborative relationships with external organizations to acquire scarce resources or to reduce their dependence on others (see Hillman et al., 2000; Hofer et al., 2012). Indeed, an organisation may come to ‘depend on the resources traded in these exchanges for survival’ (Banaszak-Holl et al., 1996, p. 99).

The corporate board is an important means for achieving such goals: its members are a primary connection between the firm and its external environment (Zahra and Pearce, 1989; Nicholson and Kiel, 2003). Members who serve on multiple boards may be able to contribute yet further because they acquire skills, experience, networks and business knowledge from their governing roles in multiple institutions.

Moreover, RDT implies that appointing directors with more influence and better access to key resource networks could support a proactive strategy to absorb the critical elements of environmental uncertainty into the firm (Pearce and Zahra, 1992; Wagner et al., 1998; Hillman et al., 2000). We then posit that directors who serve on the boards of high-profile firms could bring valuable experience and connectivity in professions and communities as well as better certification abilities to the firm (Loderer and Peyer, 2002; Ferris et al., 2003; Gupta et al., 2008; Clements et al., 2015a,b). Thus, these directors are expected to help the firm in obtaining valued resources, establishing legitimacy, providing advice and counsel and exchanging information back and forth between the firm and its external environment (Tian et al., 2011; Barroso-Castro et al., 2016).

To test our hypothesis, we identify at least one ‘category’1 of multiple directors that may be particularly valuable to their firm in this respect: this is the director who sits on the board or boards of complex and/or particularly well-connected entities (‘prestigious’ directorships). This identification strategy is particularly applicable for New Zealand firms. Given the geography of the country, these firms are likely to experience difficulties in obtaining an optimum mix of skills, expertise and linkages regarding the board. A specific factor affecting New Zealand board composition is the relatively small pool of directors (Reddy et al., 2008; Wells and Mueller, 2014).

We argue that the knowledge and skills prestigious directors bring to the table – characterised as ‘environmental’, ‘symbiotic’ or ‘collaborative’ in resource dependency terms – contribute directly to the success of the firms they serve.

The extant literature emphasises that certain isolated or individual board members may be more valuable to a firm than others. These characteristics are primarily built upon their current and past professional experiences and actions in similar positions (Zajac and Westphal, 1996; Carpenter and Westphal, 2001; Johnson et al., 2013). For example, improvements may accrue from directors who serve on boards of listed (Loderer and Peyer, 2002), reputable (Kim and Cannella, 2008; Eminet and Guedri, 2010) or larger firms (Clements et al., 2015a). This implies that directors of prestigious firms are likely to be competent and reputable directors.

These characteristics have not been, however, conceptualised or combined in any coherent manner. RDT allows us to suggest ‘how’ and ‘why’ a ‘prestigious’ multiple directorship may lead to improved performance in the larger sense. This is illustrated by four activities, roles and contributions known to be associated with ‘prestigious’ board membership.

The first of these is to do with the diversity of experience a multiple director will acquire in prestigious firms. Smaller firms do not offer the sort of strategic decision-making or agent-monitoring, which are common to large or high-profile organisations (Carpenter and Fredrickson, 2001; Carpenter and Westphal, 2001; Kroll et al., 2008; Bendickson et al., 2015). The knowledge and skills generated from the board experience of prestigious firms may allow directors to provide alternative viewpoints on strategic and governance problems and concerns. It follows that experience gained at prestigious firms can help directors to broaden the level of knowledge and skills necessary to perform their advising and monitoring duties at an optimum level (Carpenter and Fredrickson, 2001; Cashman et al., 2013; Field et al., 2013).

The second draws from higher meeting frequency and related high-level discussions often found to occur in ‘prestigious’ firms. This allows directors to grow from these interactions and information exchanges (Davis, 1991; Carter and Lorsch, 2004). Directors may acquire knowledge that helps them identify opportunities, threats, competitive conditions, technologies or regulatory changes relevant to all the boards on which they serve (Haunschild and Beckman, 1998; Kor, 2003; Clements et al., 2015b). Knowledge acquired on ‘prestigious’ boards can be applied to other circumstances, which in turn may enable them to better advise on issues that tend to affect the larger business community (Westphal, 1999; Hillman et al., 2000; Westphal and Fredrickson, 2001).

The third contribution refers to the negotiating and networking skills likely to be acquired in multiple directors’ association with ‘prestigious’ firms. Because of complex operating environments, directors in ‘prestigious’ firms may engage with diverse groups and manage complex, global business transactions. This allows directors opportunities to build on their connections with external constituencies as well and thereby collaborate or obtain access to critical resources (Bazerman and Schoorman, 1983; Zahra and Pearce, 1989; Burt, 1992; Kor and Sundaramurthy, 2009; Field et al., 2013). By contrast, the directors of non-prestigious firms are more likely to be restricted in their commercial contacts and have less access to such external connections or the benefit that they may bring.

The fourth contribution relates to an individual’s very presence on a ‘prestigious’ board. The existence of known individuals on the board may enhance a board’s reputation and enable a wider access to informal as well as formal resources. Companies with directors on high-profile boards are said to attract certifications, access to resources, improved loan rates or terms due to the value of their association (Mizruchi, 1996; Kiel and Nicholson, 2006; Barroso-Castro et al., 2016). Their presence comprises an endorsement that can create market advantages (Kiel and Nicholson, 2006; Fich and Shivdasani, 2007; Mullens, 2014). In contrast, the non-prestigious firm may enjoy only passing involvement with influential externals (Shu and Lewin, 2017), lessening their ability to contribute to a wider business reputation.

In conclusion, RDT explains why the collaborative and knowledge-based relationships acquired from ‘prestigious’ board experience are important. It is a theory that also allows us to suggest that firms may be able to enhance their performance by appointing ‘prestigious’ directors who can contribute their unique skills and connections. That is, firms with a greater ‘prestigious’ MDS public presence may be better able to form the external, symbiotic and collaborative relationships on which firms can ultimately come to rely.

H1: Better firm accounting performance is associated with a higher number or proportion of prestigious MDS, relative to the number or proportion of non-prestigious MDS, on the board (both current and future).

H2: Better firm market performance is associated with a higher number or proportion of prestigious MDS, relative to the number or proportion of non-prestigious MDS on the board (both current and future).

Both hypotheses are tested using the methods described in the next section.

3 Research design

For the purposes of the study, multiple directors (MDS) are defined as any governing board member of New Zealand listed entities who concurrently sits on any other governing board. Each board position a multiple director holds which is outside the firm being studied is considered to be one multiple directorship (MDS) position. So, a board member for New Zealand listed Company X who also holds board positions on Company Y and Company Z has two MDS. Each MDS is further classified as either ‘prestigious’ or ‘non-prestigious’. By using these terms and their measure, the average number and proportion of ‘prestigious’ versus ‘non-prestigious’ MDS on each governing board can be determined.

The classification into ‘prestigious’ or ‘non-prestigious’ categories is based on several fundamental firm characteristics that indicate the level of global experience, high-level connectivity, knowledge, technical-tax requirements and/or certification abilities likely to be acquired by members of their governing board. In particular, we employ a number of fundamental firm characteristics – such as listing status, ownership type, country of origin, reputation and industry affiliation – to make this ‘prestige’ classification. They come to include any MDS positions in the Top 100 NZ companies, and any publicly listed entities from both Australia and New Zealand share markets. ‘Prestigious’ firms also include financial institutions due to their extensive regulatory obligations and global relationships. Entities that are listed or are otherwise based in overseas nations are included because of their global connectivity and likely complexities associated with dealing with overseas practice and regulation. Finally, positions in certain governmental entities are included because of their ability to provide access to regulatory knowledge, lobbying, advocacy, building a constituency and forming alliances (Hillman and Hitt, 1999; Hillman et al., 2004). They include state-owned companies, Crown companies, Crown agents and market-related regulatory organisations. The ‘non-prestigious’ category includes all others: private and family firms and, in the absence of other prestigious characteristics, domestic companies.

3.1 Sample and data

Our sample comprises board information derived from all publicly listed companies on the New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZX) whose financial reporting periods end from January 2005 to December 2014. The sample inspected is all available data on NZX listed companies with complete data for the dependent, independent and control variables for at least three years or more within the sample period. The final sample of companies comprises the boards of 116 different firms, or over time, 1,022 firm-year observations. The population is diverse. It includes, for example, firms of different ages, industry and maturity, discontinued (delisted) firms and newly started firms. The data on MDS is hand-collected from annual reports (Table 1).

| Panel A: Selection criteria | Number of observations |

| Sample firms | |

| Total firms listed on the Event section of NZX database as at 31 December 2014 | 444 |

| Less NZDX firms listed on the Event section of NZX database | (98) |

| Less firms delisted before 2005 | (134) |

| Less currently listed firms not issuing at least three annual reports since being listed on the NZX | (49) |

| Less currently delisted firms not having at least three annual reports before being delisted from the NZX | (18) |

| Less firms not having MDS information available in the annual report | (29) |

| Total firms in the final sample | 116 |

| Panel B: Sample firm-years | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of years for which data available | No. of firms | Firm-years |

| 10 years | 79 | 790 |

| 9 years | 5 | 45 |

| 8 years | 8 | 64 |

| 7 years | 6 | 42 |

| 6 years | 4 | 24 |

| 5 years | 6 | 30 |

| 4 years | 3 | 12 |

| 3 years | 5 | 15 |

| Total | 116 | 1,022 |

- Panel A shows the procedure for derivation of the sample number of firms. This study starts with all firms included in the NZX Data Company Research from 2005 to 2014 and restricts the sample to those firms that meet certain criteria. Panel B presents the distribution of the sample, showing total number of firm-years with the breakdowns into number of years and number of firms. This specifies that the number of firms is not equal over the years, which indicates that some firms had been delisted, and others are newly listed on the NZX during the 2005–2014 period.

The population of MDS consists of all board positions held by directors which are outside the firm being studied. MDS is therefore measured by counting the number of directorships held in other companies (excluding subsidiaries and associated firms of the company studied) by all the board members of a given firm. For example, a firm with four directors, one of whom sits on two additional boards and another of whom sits on one additional board, has three MDS. Their proportion is the number of MDS divided by the number of board members which is, in this case, 3/4 or 75%. In total, we find 22,166 MDS of which 7,011 are Prestigious and 15,155 are Non-Prestigious. These MDS together form the population (and sample) used for the empirical analysis. See also Table A1 in the Appendix, where we rely on data from Air New Zealand to demonstrate our approach.

Annual reports are retrieved from the NZX Data Company Research website. Other required firm characteristics and governance-related information are retrieved from different data bases including Compustat, annual reports, company websites, the NZX website and other public documents about listed companies on the NZX. Market information is collected from the NZX Data Company Research, Datastream and online data sources.

3.2 Measures of firm performance

This study employs both accounting-based and stock market-based measures to proxy firm performance of current year (t) as well as future years, t + 1, t + 2 and t + 3 to test both short-term and long-term performance implications of MDS. Two alternative proxies are used for accounting performance: return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE).

Tobin’s Q ratio (Q) and the stock return (R) are employed to proxy market-based firm performance. R is the mean annual stock return over 12 months preceding the financial year-end. Q is approximated by taking the ratio of (i) the market value of the assets as the sum of market value of equity, market value of preference share capital, book value of convertible debt and book value of debt, and (ii) the minimum replacement cost of the assets as measured by the book value of total assets (Lindenberg and Ross, 1981). Although studies have begun to view Tobin’s Q as an imperfect measure of firm performance (see Dybvig and Warachka, 2015; Bartlett and Partnoy, 2018), Q is a widely used measure of market performance in New Zealand studies. Hence, we use Tobin’s Q to facilitate comparison with existing NZ studies (Table 2).

| Panel A: Dependent variables (Transformation Technique – Inverse Hyperbolic Sine Function) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Meaning | Description (proxy) |

| PerfACC | Accounting firm performance | Profit Margin, Return on Assets and Return on Equity |

| Margin | Profit margin | Pre-tax Operating Profit (EBIT) as a percentage of Sales (Source: Compustat, Annual Report) |

| ROA | Return on assets | Net income before interest and tax as a percentage of average total assets (Source: Compustat, Annual Report) |

| ROE | Return on equity | Net income after tax as a percentage of average shareholder’s equity (Source: Compustat, Annual Report) |

| PerfMKT | Market firm performance | Tobin’s Q and Stock Return |

| Q | Tobin’s Q | The ratio of market value of firm (Market value of equity + Market value of preferred share + Book value of convertible debt + book value of debt) and Book value of assets (Source: Compustat, Annual Report, NZX Data Company Research, Datastream) |

| R | Stock return | Annual share return over 12 months preceding the financial year-end, using Datastream return index (Source: NZX Data Company Research, Datastream) |

| Perft+i | Future performance | One, two and three year ahead Firm performance (Respective Measures) |

| Panel B: Independent variables (Transformation Technique – Inverse Hyperbolic Sine Function) | ||

| Board MDS | Average of total MDS | The number of total directorships held by all the directors on a corporate board scaled by board size (Source: Annual Reports) |

| Prestg. MDS | Average of prestigious MDS | The number of prestigious directorships held by all the directors on a corporate board scaled by board size (Source: Annual Reports) |

| Non-Prestg. MDS | Average of non-prestigious MDS | The number of other directorships held by all the directors on a corporate board scaled by board size (Source: Annual Reports) |

| Panel C: Control variables | ||

| Size | Firm size | Natural logarithm of the book value of total assets at the end of each year (Source: Compustat, Annual Report) |

| Age | Firm age | Natural logarithm of the number of years from which a firm is listed on NZX (Source: NZX Data Company Research) |

| Leverage | Debt/asset ratio | Natural logarithm of total liabilities over total assets (Source: Compustat, Annual Report) |

| Perft | ROAt and ROEt | ROA and ROE at the end of current financial year (Source: Compustat, Annual Report) |

| BoardSize | Board size | Number of directors on the board (Source: Annual Report) |

| Outside Director | Proportion of outside directors | Proportion of outside (non-executive) directors on the board (Source: Annual Report) |

| Beta | Equity beta | The firm’s equity beta, estimated by using monthly stock returns data over the past three years (36 months) or available months (if not available for past 36 months) and the S&P/NZX 50 total index as a proxy for market returns (Source: NZX Data Company Research, Datastream, Online Source (Yahoo Finance)) |

| B2M | Book-to-market ratio | Ratio of book value and market capitalisation of firm’s equity at the end of the financial year (Source: NZX Data Company Research, Datastream) |

| GFC | Global financial crisis | A binary variable for GFC periods, 2008, 2009 and 2010, i.e. a dummy variable which equals 1 if the period is either 2008 or 2009 or 2010, otherwise 0 (Source: Annual Report) |

| Loss | Loss dummy | A binary variable equals 1 if the firm incurs a net loss during the (current financial) year, otherwise 0 (Source: Annual Report) |

| High Levg | High leverage dummy | A binary variable equals 1 if the leverage (TL/TA) of a firm is >0.8, otherwise 0 (Source: Annual Report) |

| Industry | Industry dummy variables | Seven dummy variables to identify the industry affiliation of each firm/year with Idj = 1 for firm/years under industry j and 0 otherwise with Goods being the 'base industry’, hence excluded (Source: Annual Report) |

- This table presents the list of variables including name, meaning and description of proxies used in the firm performance model.

3.3 Measures of multiple directorships

This study measures MDS by categorising them into two groups, based on the relative ‘prestige’ of appointing firms instead of simply counting the numbers of MDS. Firstly, ‘prestigious MDS’ includes directorships in ‘prestigious’ firms and are measured as the total/average number of directorships in prestigious firms held by the board (all the directors) of a given firm in a specific period. Secondly, non-prestigious MDS includes directorships in ‘non-prestigious’ firms and are measured as the total/average number of directorships in non-prestigious firms held by the board (all the directors) of a given firm in a specific period.2

Following prior studies (Fich and Shivdasani, 2006; Ahn et al., 2010; Cashman et al., 2012; Field et al., 2013; Pathan and Faff, 2013; Bhagat et al., 2015), this study controls for a number of variables in both accounting and market performance models. These are firm size (Size), firm age (Age) and leverage (Leverage), which are expected to be associated with both categories of corporate performance. Size is measured as the natural logarithm of the end of year firm’s total assets, Age is measured as the natural logarithm of listing tenure, and Leverage is calculated as the natural logarithm of total liabilities over total assets at the end of the financial year. Finally, industry variation is captured using industry dummies in both models. Based on NZX industry categories,3 seven dummy variables are included to control the industry affiliation of each firm/year. The ‘Goods’ industry is considered as the ‘base industry’ and coded as such.

In addition, board size (BoardSize), proportion of outside directors (OutsideDir), and an additional control variable, performance in the current year (Perft), measured by respective performance variables (ROAt and ROEt) are included as right-hand side variables in each future years’ accounting performance regressions. In addition, three binary variables are included in the accounting performance models. GFC is included as a control to assess how the financial crisis influenced the relationship between MDS and firm performance; it equals 1 for the years 2008–2010 and 0 otherwise. HighLevg, which equals 1 if the leverage of a firm is >0.8, otherwise 0, is included to identify the different pattern of relationship between MDS and firm performance (if any) of firms having high leverage. Following prior studies (Hwang et al., 1996; Joos and Plesko, 2005; Darrough and Ye, 2007), Loss, which equals 1 if the firm incurs a loss during the current financial year, otherwise 0, is included to identify the different pattern of relationship between MDS and firm performance (if any) of firms incurring loss.

In the market performance model, two additional variables, equity beta (Beta) and book-to-market (B2M), are included to control the risk factors about a firm's market performance (Klein, 1998; Lewellen, 1999). The firm’s equity beta is estimated by using monthly stock returns data over the past 36 months. The S&P/NZX 50 total index acts as a proxy for market returns; book-to-market is calculated as the ratio of book value and the market capitalisation of a firm’s equity at the end of the financial year.

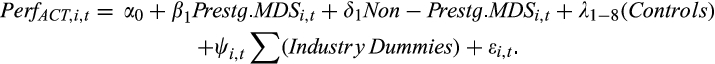

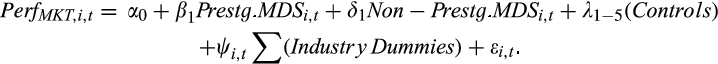

3.4 Empirical model

()

() ()

()3.5 Estimation method

For both sets of tests, we employ OLS regression models. The regression models rely on p-values that account for two-dimensional clusters, by both panels (i.e., by firms (i) and time period (t)) to address random unobserved serial and cross-sectional correlation, respectively (if any), in residuals (Petersen, 2009). In addition, we rely on several alternative methods to address different econometric issues related to quantitative analysis including firm fixed effects (FE), the first-difference estimation and generalised method of moments (GMM).

Both multiple directorships and firm performance are transformed using the ‘inverse hyperbolic sine’ (IHS) function [sinh−1(x)] to reduce the problem with skewness and heteroscedasticity. We use this instead of logs, as logs cannot accommodate negative and zero values, and our measures of both MDS and firm performance contain zero and negative values.

3.6 Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

Tables 3 presents the descriptive statistics for various board, MDS and firm characteristic variables. As reported in Panel A of Table 3, board size (BoardSize) ranges from 3 to 13, with a mean (median) of 6.1 (6.0). These numbers are comparable to those reported for existing New Zealand studies, such as Hossain et al. (2001), Prevost et al. (2002), Bhuiyan (2010), Dunstan et al. (2011), Li (2013), and Fauzi and Locke (2012). The mean (median) proportion of outside (non-executive) directors (OustsideDir) over the sample period is 84% (86%), ranging from 20 to 100%.

| Panel A: Board and MDs variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1,020 | Mean | Min. | Percentiles | Max. | ||||

| 5 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 95 | ||||

| BoardSize (No., N = 6238) | 6.1 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 13.0 |

| OutsideDir (%) | 84.0 | 20.0 | 57.0 | 75.0 | 86.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Total Board MDS (No., N = 22166) | 21.7 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 11.0 | 18.0 | 28.0 | 50.0 | 146.0 |

| Total Prestg. MDS (No., N = 7011) | 6.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 17.9 | 32.0 |

| Total Non-Prestg. MDS (No., N = 15155) | 14.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 11.0 | 20.0 | 41.0 | 127.0 |

| Board MDS (No.) | 3.6 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 8.2 | 24.3 |

| Prestg. MDS (No.) | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 5.0 |

| Non-Prestg. MDS (No.) | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 7.5 | 21.4 |

| N/DS. Post. (No.) | 5.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 19.0 | 45.0 |

| Panel B: Firm performance measures | ||||||||

| EBIT ($NZ mil) | 274.85 | −1,092 | −5.08 | 2.10 | 19.57 | 71.53 | 665.10 | 10,740.00 |

| NPAT ($NZ mil) | 177.69 | −435 | −15.52 | 0.21 | 10.30 | 48.30 | 458.00 | 7,561.00 |

| ROA (%) | 5.52 | −821.62 | −2.84 | 1.63 | 7.07 | 13.00 | 26.51 | 1247.21 |

| ROE (%) | 3.66 | −396.77 | −29.40 | 0.61 | 7.12 | 14.10 | 27.29 | 98.37 |

| R | 11.51 | −99.30 | −52.36 | −14.50 | 8.76 | 28.35 | 81.59 | 339.96 |

| Q | 2.30 | 0.39 | 0.66 | 0.96 | 1.18 | 1.79 | 5.34 | 260.31 |

| Panel C: Firm-specific variables | ||||||||

| Size-TA ($NZ mil) | 12,822.00 | 0.03 | 4.44 | 57.68 | 231.54 | 1218.59 | 8713.32 | 772,092.00 |

| Age (years) | 14.51 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 19 | 46 | 67 |

| Leverage (ratio) | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.63 | 0.96 | 1 |

| B2M | 1.29 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.51 | 0.90 | 1.41 | 3.43 | 31.33 |

| Beta | 0.75 | −8.00 | 0.44 | 0.24 | 0.70 | 1.13 | 2.03 | 25.75 |

| HighLevg (binary, N(1) = 119) | 0.12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Loss (binary, N(1) = 236) | 0.23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

- This table presents descriptive statistics of variables (untransformed) from NZX listed companies over 2005–2014. See Table 2 for variable definitions. Amounts are reported in millions $NZD.

At board level, the mean (median) number of total MDS (without categorisation) of a typical NZX board is 21.7 (18.0) with a range of 1 (Windflow Technology Limited) to 146 (Metlifecare Limited). Among the total MDS per board, the mean (median) number of total prestigious MDS is 6.9 (5.0) and the mean (median) number of total non-prestigious MDS is 14.8 (11.0).

At director level (total MDS scaled by board size), the mean (median) number of MDS per director is 3.6 (3.0). Among the total MDS per director, the mean (median) number of prestigious MDS (Prestg. MDS) is 1.1 (1.0), while the mean (median) number of non-prestigious MDS (Non-Prestg. MDS) is 2.5 (1.9).

Thus, the number of non-prestigious MDS is more than twice the number of prestigious MDS, showing that the majority of MDS on NZX boards are from non-prestigious companies. This confirms a unique pattern of MDS in New Zealand, where directors usually hold a higher proportion of directorships in non-listed companies relative to listed companies (Boyle and Ji, 2013; Li, 2013; Brown and Roberts, 2016).

In addition to corporate directorships, New Zealand directors often hold several other positions, such as advisory positions, chairmanships or trusteeships in non-trading and government organisations. The mean (median) value of non-directorship positions (N/DS. Post) of a corporate board is 5.7 (3.0) with a range from 0 to 45. As discussed in the prior literature, these positions could contribute to the busyness of a corporate board (Fich and Shivdasani, 2006; Cashman et al., 2012).

The descriptive statistics of performance variables are presented in Panel B of Table 3. The mean (median) earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) and net profit after tax (NPAT) are $274.85 m ($19.57 m) and $177.69 m ($10.30 m), indicating that these are skewed with the maximum numbers approximately 16 times larger than the numbers at the 95th percentile. The mean (median) return on assets (ROA) is 5.52% (7.07%) and the sample mean (median) return on equity (ROE) is 3.66% (7.12%). The mean (median) percentage of annual stock returns (R) is 11.51% (8.76%), showing that stock returns of New Zealand listed companies are considerably higher than book returns (ROA and ROE). The sample mean (median) Tobin’s Q is 2.30 (1.18). Quartile values of the measures of firm accounting performance show that the lower 25% of all values (the loss dummy is equal to 1 for 236 firm-years, which is 23.1% of the total sample) of NZX companies incur a loss within the sample period.

Panel C of Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics of the other firm-specific variables. The sample mean (median) book value of total assets (Size) is $12.82 billion4 ($231.54 m) with a range of $0.03 m to $7,72,092 m. The average (median) firm age (Age) is 14.5 years (11 years) which resembles the mean value shown in prior New Zealand studies such as Li (2013). The mean (median) leverage (Leverage) is 47% (45%) which is considerably larger than that of Australian firms; for example, Monem (2013) reports that the mean (median) leverage of a sample of Australian firms is 34.9% (29.6%). The mean stock beta (Beta) is 0.75 (0.70), which indicates less risky stock price of New Zealand firms.

The summary statistics of the high leverage dummy (HighLevg) indicate that about 10% of NZX companies (N = 119) hold debt which is at least 80% of their total assets. Among the observations of highly leveraged firms, 34 firm-years have a negative book value of equity. We cap the highest level of leverage at 1 as having total liabilities greater than total assets is improbable. The mean (median) book-to-market ratio (B2M) is 1.29 (0.90), suggesting that the New Zealand listed companies are not significantly undervalued or overvalued.

Table 4 presents Pearson pairwise sample correlations between variables. The correlation coefficients between MDS and performance measures are largely consistent with expectations with a few exceptions. For example, in contrast to all other performance variables, Tobin’s Q is inversely correlated with both categories of MDS and both are statistically significant. These univariate indicators suggest that firm performance (except Tobin’s Q) is positively associated with prestigious MDS, while negatively associated with non-prestigious MDS. None of the correlation coefficients recorded in Table 4 exceeds the 0.8 threshold, which indicates less likelihood of multicollinearity problems in regression models (Pallant, 2005). The highly positive correlation between firm size and board size, as well as firm size and prestigious MDS indicate that both board size and prestigious MDS increase with firm size.

| Variables (N = 1,020) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Margin | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| (2) Q | −0.22*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| (3) ROA | 0.66*** | −0.17*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| (4) ROE | 0.31*** | −0.05* | 0.40*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| (5) R | 0.06** | 0.17*** | 0.12*** | 0.25*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| (6) Prestg. MDS | 0.24*** | −0.11*** | 0.17*** | 0.17*** | 0.09*** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| (7) Non-Prestg. MDS | −0.12*** | 0.21*** | −0.09*** | −0.11*** | 0.03 | 0.05* | 1.00 | ||||||||

| (8) Size | 0.31*** | −0.46*** | 0.16*** | 0.32*** | 0.07** | 0.39*** | −0.23*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| (9) Age | 0.00 | −0.14*** | 0.11*** | 0.13*** | 0.09*** | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.20*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| (10) Leverage | 0.07** | 0.14*** | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.05* | −0.01 | 0.22*** | 0.07** | 1.00 | |||||

| (11) BoardSize | 0.10*** | −0.16*** | 0.08*** | 0.23*** | 0.08*** | 0.10*** | −0.13*** | 0.65*** | 0.19*** | 0.20*** | 1.00 | ||||

| (12) OutsideDir | 0.10*** | −0.21*** | 0.07** | 0.06** | 0.03 | 0.10*** | 0.03 | 0.29*** | 0.23*** | 0.11*** | 0.34*** | 1.00 | |||

| (13) Beta | −0.13*** | 0.14*** | −0.18*** | −0.16*** | 0.05* | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06** | 0.07** | −0.04 | 1.00 | ||

| (14) B2M | −0.07** | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.19*** | −0.28*** | −0.12*** | 0.08*** | −0.36*** | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.27*** | −0.00 | −0.11*** | 1.00 | |

| (15) LOSS | −0.07*** | 0.15*** | 0.16*** | −0.07** | −0.18*** | −0.18*** | 0.01 | −0.44*** | −0.10*** | −0.02 | −0.29*** | −0.14*** | 0.07** | 0.30*** | 1.00 |

- This table shows the Pearson correlation matrix for MDS, firm performance and control variables. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at the 0.1, 0.05 and 0.01 levels. See Table 2 for variable definitions.

4 Empirical results

The main results are presented in this section, divided between the two dependent variables of accounting performance and market performance.

4.1 Main results: MDS and accounting performance

The regression results of MDS and current year accounting performance are summarised in Table 5. Panel B of Table 5 shows that the F-statistics are statistically significant at the 1% level, which suggest a good overall fit for the models in estimating accounting firm performance among New Zealand companies. The R2 values are 18.3% and 44.7%, respectively, for ROA and ROE. The results suggest that the two categories of MDS, prestigious MDS and non-prestigious MDS, explain over 18% of variations in ROA and 44% of variations in ROE, with a higher explanatory power in explaining ROE than ROA. Panel C of Table 5 shows that the average variation inflation factor (1.66) for both models indicate that multicollinearity among the explanatory variables is unlikely to be a concern in estimating the regression equations.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | ROE | |||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.034 | 0.67 | 0.087 | 0.07* |

| Prestg. MDS | 0.086 | 0.10* | 0.053 | 0.03** |

| Non-Prestg. MDS | −0.033 | 0.08* | −0.020 | 0.07* |

| Size | −0.020 | 0.60 | −0.005 | 0.74 |

| Age | 0.073 | 0.03** | 0.045 | 0.02** |

| Leverage | 0.040 | 0.19 | −0.003 | 0.82 |

| HighLevg | −0.125 | 0.07* | −0.089 | 0.07* |

| BoardSize | 0.002 | 0.83 | 0.007 | 0.19 |

| OutsideDir | 0.056 | 0.56 | −0.068 | 0.20 |

| GFC | 0.014 | 0.56 | −0.025 | 0.01*** |

| Loss | −0.234 | 0.00*** | −0.285 | 0.00*** |

| Finance | 0.015 | 0.74 | 0.056 | 0.19 |

| Service | −0.015 | 0.54 | 0.026 | 0.18 |

| Investment | 0.075 | 0.34 | −0.019 | 0.62 |

| Property | −0.012 | 0.73 | 0.000 | 1.00 |

| Energy | −0.108 | 0.01*** | −0.076 | 0.01*** |

| Primary | −0.057 | 0.08* | −0.039 | 0.09* |

| Panel B: Model fits | ||

|---|---|---|

| R 2 | 0.183 | 0.447 |

| F-value | 14.29 | 28.69 |

| Prob > F | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 1,009 | |

| Panel C: Regression diagnostics | |

|---|---|

| AVIF (max) | 1.66 (3.06) |

| 2D cluster SE | Firm ID – 117 and Year-10 |

| Panel D: Wald test | ||

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient comparison (F stat) | ||

| Prestg. MDS = Non-Prestg. MDS | 3.47** | 4.58** |

- This table presents the results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of Equation (1) for two accounting-based firm performance measures, ROA and ROE at the end of the year. The two explanatory variables are Prestigious MDS and Non-Prestigious MDS. The regression models rely on p-values that account for two-dimensional clusters, by both panels (i.e., by firms (i) and time (t)). AVIF is the average ‘variance inflation factor’, which indicates the degree of collinearity problem among the regressors. The Wald (1943) test is used to assess the difference between coefficients of the respective estimates. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. See Table 2 for definitions of dependent, independent and control variables.

Panel A of Table 5 reveals that prestigious MDS on the board are associated with better accounting performance represented by ROA and ROE. The associated estimated coefficients on prestigious MDS are positive, 0.086 for ROA and 0.053 for ROE, which are statistically significant. With regard to non-prestigious MDS, Panel A of Table 5 shows that the estimated coefficients are negative, −0.033 for ROA and −0.020 for ROE, which are also statistically significant, suggesting that non-prestigious MDS are negatively associated with the firm’s accounting performance. The economic significance of these results is notable: for example, an increase in average prestigious MDS by 1 is associated with an 8.6% increase in ROA, while an increase in average non-prestigious MDS by 1 is associated with a drop in ROA by approximately 3.3%.

Tables 6 and 7 report the results of regressions of future firm performance. The R2 values are 21.3%, 13.3% and 9.0% for the ROA model and 24.8%, 24.2% and 21.7% for the ROE model, respectively, for the subsequent years at times: t + 1, t + 2 and t + 3.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ROA One year ahead |

ROA Two years ahead |

ROA Three years ahead |

||||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.097 | 0.34 | 0.076 | 0.59 | 0.029 | 0.83 |

| Prestg. MDS | 0.062 | 0.06* | 0.099 | 0.05** | 0.117 | 0.02** |

| Non-Prestg. MDS | −0.030 | 0.08* | −0.042 | 0.07* | −0.045 | 0.06* |

| Size | −0.012 | 0.55 | −0.030 | 0.33 | −0.054 | 0.06* |

| Age | 0.062 | 0.05** | 0.065 | 0.08* | 0.031 | 0.30 |

| Leverage | 0.043 | 0.15 | 0.020 | 0.57 | −0.001 | 0.98 |

| HighLevg | −0.067 | 0.16 | −0.125 | 0.16 | −0.008 | 0.94 |

| ROAt | 0.139 | 0.00*** | 0.037 | 0.06* | 0.020 | 0.64 |

| BoardSize | 0.003 | 0.73 | 0.009 | 0.30 | 0.027 | 0.02** |

| OutSideDir | −0.062 | 0.60 | −0.044 | 0.79 | −0.060 | 0.71 |

| GFC | 0.008 | 0.65 | −0.002 | 0.95 | −0.010 | 0.65 |

| Loss | −0.146 | 0.00*** | −0.151 | 0.00*** | −0.103 | 0.00*** |

| Finance | −0.005 | 0.91 | 0.035 | 0.45 | −0.015 | 0.81 |

| Service | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.001 | 0.97 | 0.011 | 0.78 |

| Investments | 0.080 | 0.26 | 0.093 | 0.28 | 0.081 | 0.34 |

| Property | 0.005 | 0.85 | 0.001 | 0.96 | 0.018 | 0.62 |

| Energy | −0.075 | 0.11 | −0.092 | 0.10* | −0.077 | 0.30 |

| Primary | −0.035 | 0.28 | −0.050 | 0.17 | −0.038 | 0.37 |

| Panel B: Model fits | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R 2 | 0.213 | 0.133 | 0.090 |

| F-value | 8.63 | 6.18 | 3.89 |

| Prob > F | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 894 | 779 | 665 |

| Panel C: Regression diagnostics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AVIF (max) | 1.66 (3.11) | ||

| 2D cluster SE | ID – 115 and Year −9 | ID −114 and Year – 8 | ID −110 and Year −7 |

| Panel D: Wald test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient comparison (F stat) | |||

| Prestg. MDS = Non-Prestg. MDS | 5.64*** | 4.88*** | 6.62*** |

- This table presents the results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of Equation (1) for ROA in future years 1, 2 and 3. The two explanatory variables are Prestigious MDS and Non-Prestigious MDS. The regression models rely on p-values that account for two-dimensional clusters, by both panels (i.e., by firms (i) and time (t)). AVIF is the average ‘variance inflation factor’, which indicates the degree of collinearity problem among the regressors. The Wald (1943) test is used to assess the difference between coefficients of the respective estimates. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. See Table 2 for definitions of dependent, independent and control variables.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | ROE | ROE | ||||

| One year ahead | Two years ahead | Three years ahead | ||||

| Coef | p-value | Coef | p-value | Coef | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.027 | 0.64 | 0.041 | 0.51 | 0.024 | 0.77 |

| Prestg. MDS | 0.051 | 0.04** | 0.064 | 0.03** | 0.051 | 0.18 |

| Non-Prestg. MDS | −0.014 | 0.27 | −0.017 | 0.21 | −0.012 | 0.41 |

| Size | 0.007 | 0.62 | −0.001 | 0.96 | 0.009 | 0.56 |

| Age | 0.044 | 0.02** | 0.038 | 0.03** | 0.034 | 0.08* |

| Leverage | 0.007 | 0.74 | 0.006 | 0.77 | −0.005 | 0.76 |

| HighLevg | −0.066 | 0.22 | −0.078 | 0.20 | −0.139 | 0.06* |

| ROEt | 0.005 | 0.20 | 0.009 | 0.01*** | 0.010 | 0.04** |

| BoardSize | 0.007 | 0.40 | 0.012 | 0.11 | 0.014 | 0.14 |

| OutsideDir | −0.076 | 0.26 | −0.132 | 0.09* | −0.189 | 0.13 |

| GFC | −0.039 | 0.00*** | −0.017 | 0.37 | 0.000 | 0.99 |

| Loss | −0.151 | 0.00*** | −0.136 | 0.00*** | −0.083 | 0.00*** |

| Finance | 0.051 | 0.31 | 0.060 | 0.22 | 0.094 | 0.17 |

| Service | 0.050 | 0.05** | 0.066 | 0.01*** | 0.090 | 0.01*** |

| Investments | −0.016 | 0.72 | −0.022 | 0.67 | −0.014 | 0.82 |

| Property | 0.012 | 0.67 | 0.018 | 0.59 | 0.021 | 0.59 |

| Energy | −0.066 | 0.18 | −0.064 | 0.25 | −0.039 | 0.53 |

| Primary | −0.025 | 0.45 | −0.020 | 0.46 | −0.006 | 0.89 |

| Panel B: Model fits | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R 2 | 0.248 | 0.242 | 0.217 |

| F-value | 12.93 | 9.14 | 8.58 |

| Prob > F | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 894 | 779 | 665 |

| Panel C: Regression diagnostics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVIF (Max) | 1.66 (3.06) | |||

| 2D cluster SE | ID – 115 and Year-9 | ID −114 and Year-8 | ID −110 and Year-7 | |

| Panel D: Wald test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient comparison (F stat) | |||

| Prestg. MDS = Non-Prestg. MDS | 3.71** | 4.5** | 1.73 |

- This table presents the results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of Equation (1) for ROE in future years 1, 2 and 3. The two explanatory variables are Prestigious MDS and Non-Prestigious MDS. The regression models rely on p-values that account for two-dimensional clusters, by both panels (i.e., by firms (i) and time (t)). AVIF is the average ‘variance inflation factor’, which indicates the degree of collinearity problem among the regressors. The Wald (1943) test is used to assess the difference between coefficients of the respective estimates. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. See Table 2 for definitions of dependent, independent and control variables.

The regression results shown in the second row of Panel A of Table 6 reveal that prestigious MDS are positively associated with the one-, two- and three-year ahead ROA, and the results are statistically significant (coefficients = 0.062, 0.099 and 0.117, respectively, for the one-, two- and three-year horizons, respectively). The economic significance of these results is notable, showing an increasing trend over the period. For example, an increase in average prestigious MDS by 1 in the current year is associated with 6%, 10% and 12% ROA increase in the subsequent years. On the other hand, the estimated coefficients for non-prestigious MDS in the third row of Panel A are negative and statistically significant for the three time horizons.

Table 7 shows that the relationship does not change for prestigious MDS when ROE is employed as the dependent variable, while the coefficients of non-prestigious MDS in the ROE regression are negative over the three-year horizons, albeit that these are not statistically significant.

The results of prestigious MDS and non-prestigious MDS in relation to accounting firm performance thus support the hypothesis (H1) that the predicted relationship between MDS and firm accounting performance varies with the type of MDS (prestigious and non-prestigious). A differential impact for prestigious MDS and non-prestigious MDS is consistent with those prior studies that provide evidence on the differential effects between different categories of MDS on firms’ outcomes, for example MDS between listed and non-listed firms (Loderer and Peyer, 2002), firms in related and non-related industries (Clements et al., 2015b) or larger and smaller firms (Clements et al., 2015a).

In addition, Wald statistics (Wald, 1943) summarised in Panel D of Tables 5–7 indicate that the coefficients associated with prestigious MDS and non-prestigious MDS are generally larger and significantly different from each other, which confirms the prediction that there are firm accounting ‘performance’ differences between prestigious MDS and non-prestigious MDS.

The estimated coefficients of control variables offer further insights into the performance of New Zealand firms. For instance, the statistically significant positive coefficient on firm age indicates that mature firms perform better. Likewise, the statistically significant negative coefficient of the high leverage dummy (leverage is greater than 0.8) demonstrates that firms with a higher level of debt in their capital structure perform worse. The negative coefficients of the dummy variable of global financial crisis, GFC, in the ROE model indicate that firms were less profitable during the GFC. ROA was not affected in this period, which may indicate that New Zealand firms used more debt during the GFC period.

4.2 Main results: MDS and market performance

Table 8 reports the results of the regressions between MDS and a firm’s current market performance. Panel B of Table 8 shows that the F-statistics for the regression equations are statistically significant at the 1% level, which suggests a good overall fit for the models in estimating market firm performance among New Zealand companies. The R2 values are 12.9% and 33.2%, respectively, for stock return and Tobin’s Q. The R2 values suggest that the two categories of MDS have higher explanatory power in explaining Tobin’s Q than stock return.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stock Return | Tobin’s Q | |||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.018 | 0.81 | 2.005 | 0.00*** |

| Prestg. MDS | 0.094 | 0.02** | 0.156 | 0.02** |

| Non-Prestg. MDS | 0.011 | 0.58 | 0.061 | 0.20 |

| Size | −0.052 | 0.02** | −0.314 | 0.00*** |

| Age | 0.129 | 0.00*** | −0.068 | 0.48 |

| Leverage | 0.025 | 0.25 | 0.307 | 0.00*** |

| Beta | 0.002 | 0.88 | 0.035 | 0.05** |

| B2M | −0.079 | 0.00*** | −0.061 | 0.12 |

| Finance | 0.088 | 0.05** | 0.143 | 0.38 |

| Service | 0.148 | 0.00*** | 0.000 | 1.00 |

| Investments | 0.061 | 0.28 | −0.102 | 0.51 |

| Property | 0.099 | 0.00*** | −0.216 | 0.08* |

| Energy | −0.018 | 0.70 | −0.065 | 0.56 |

| Primary | 0.060 | 0.20 | −0.096 | 0.55 |

| Panel B: Model fits | ||

|---|---|---|

| R 2 | 0.129 | 0.332 |

| F-value | 8.35 | 25.59 |

| Prob > F | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 962 | 966 |

| Panel C: Regression diagnostics | ||

|---|---|---|

| AVIF (max) | 1.48 (2.18) | 1.49 (2.18) |

| 2D cluster SE | ID – 116 and Year – 10 | |

| Panel D: Wald test | ||

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient comparison (F stat) | ||

| Prestg. MDS = Non-Prestg. MDS | 3.52* | 3.51* |

- This table presents the results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of Equation (2) for two market-based firm performance measures, Stock Return and Tobin’s Q at the end of the year. The two explanatory variables are Prestigious MDS and Non-Prestigious MDS. The regression models rely on p-values that account for two-dimensional clusters, by both panels (i.e., by firms (i) and time (t)). AVIF is the average ‘variance inflation factor’, which indicates the degree of collinearity problem among the regressors. The Wald (1943) test is used to assess the difference between coefficients of the respective estimates. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. See Table 2 for definitions of dependent, independent and control variables.

Panel A of Table 8 shows that having prestigious MDS on the board is associated with a 9.4% increase in stock return and a 0.156-point increase in Tobin’s Q. These results are significant at a 5% level, suggesting that having prestigious MDS on the board is positively associated with market performance among the NZX companies.

Regarding non-prestigious MDS, Panel A shows positive coefficients which are insignificant for both stock return (0.011) and Tobin’s Q (0.061). The results thus suggest there is no significant relationship between non-prestigious MDS and market performance. These findings lend support for hypothesis H2. In addition, the Wald statistics summarised in Panel D of Table 8 indicate that the coefficients associated with prestigious MDS and non-prestigious MDS are generally larger and significantly different from each other, which confirms the prediction of H2.

Table 9 summarises the regression results of MDS and share return for subsequent years. Panel B shows that the F-statistics for regression equations are statistically significant at the 1% level with an adjusted R2 between 5 and 6 percent. The results show that having prestigious MDS on the board is positively associated with all the three-year horizon share returns. The second row of Panel A of Table 9 shows that the coefficients for prestigious MDS on share return of one (0.047) and two (0.058) years ahead are statistically significant at the 10% and 5% level, respectively, whereas the three-year ahead share return is not significantly associated with prestigious MDS. This indicates that the effects of prestigious MDS on market performance may not continue after two years.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stock Return One year ahead |

Stock Return Two years ahead |

Stock Return Three years ahead |

||||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Intercept | −0.124 | 0.15 | −0.082 | 0.45 | −0.088 | 0.45 |

| Prestg. MDS | 0.047 | 0.10* | 0.058 | 0.05** | 0.030 | 0.39 |

| Non-prestg. MDS | 0.021 | 0.32 | 0.014 | 0.48 | 0.023 | 0.33 |

| Size | 0.004 | 0.84 | −0.004 | 0.83 | −0.002 | 0.92 |

| Age | 0.055 | 0.00*** | 0.028 | 0.43 | 0.052 | 0.06* |

| Leverage | −0.028 | 0.40 | −0.018 | 0.61 | −0.001 | 0.98 |

| Beta | 0.026 | 0.11 | 0.033 | 0.09* | 0.032 | 0.05** |

| B2M | 0.018 | 0.17 | 0.014 | 0.25 | 0.011 | 0.38 |

| Finance | 0.013 | 0.82 | −0.001 | 0.98 | −0.012 | 0.85 |

| Service | 0.115 | 0.01*** | 0.121 | 0.03** | 0.107 | 0.12 |

| Investments | −0.081 | 0.27 | −0.069 | 0.40 | −0.051 | 0.57 |

| Property | 0.071 | 0.19 | 0.088 | 0.21 | 0.086 | 0.27 |

| Energy | −0.046 | 0.37 | −0.071 | 0.26 | −0.102 | 0.11 |

| Primary | 0.018 | 0.74 | 0.059 | 0.36 | 0.060 | 0.45 |

| Panel B: Model fits | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R 2 | 0.051 | 0.055 | 0.055 |

| F-value | 3.41 | 3.29 | 3.13 |

| Prob > F | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 852 | 739 | 628 |

| Panel C: Regression diagnostics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AVIF (max) | 1.48 (2.18) | ||

| 2D cluster SE | ID – 115 and Year-9 | ID −114 and Year-8 | ID −110 and Year-7 |

| Panel D: Wald test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient comparison (F stat) | |||

| Prestg. MDS = Non-Prestg. MDS | 0.41 | 1.06 | 0.01 |

- This table presents the results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of Equation (2) for Stock Return in future years 1, 2 and 3. The two explanatory variables are Prestigious MDS and Non-Prestigious MDS. The regression models rely on p-values that account for two-dimensional clusters, by both panels (i.e., by firms (i) and time (t)). AVIF is the average ‘variance inflation factor’, which indicates the degree of collinearity problem among the regressors. The Wald (1943) test is used to assess the difference between coefficients of the respective estimates. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. See Table 2 for definitions of dependent, independent and control variables.

Regarding non-prestigious MDS, Panel A shows that the coefficients for non-prestigious MDS on share return are positive, but not statistically significant, suggesting that there is no significant association between a firm’s future market performance and having non-prestigious MDS on the board.

The regression results for the relationship between MDS and a firm’s market performance (Tables 8 and 9) also confirm hypothesis H2: the predicted relationship between MDS and firm’s market performance varies with the type of MDS (prestigious and non-prestigious). Although the findings are consistent with the prediction, the market measures of firm performance lend weaker support regarding the differences between prestigious and non-prestigious MDS compared to the results obtained employing accounting measures.

The estimated coefficients of additional control variables of market performance models (Table 8) reveal the perspective of risk in relation to performance of New Zealand firms. The statistically significant negative coefficients of firm size (fourth row of Panel A) indicate that larger firms are perceived to be riskier, therefore inducing a negative market reaction. Positive coefficients of stock beta (seventh row of Panel A) in both the market performance models (significant in the Q model) are consistent with the theoretical foundation of the capital asset pricing model. Lastly, the statistically significant negative coefficient of book-to-market (eighth row of Panel A) in the stock return model shows that undervalued firms perform worse in the stock market.

4.3 Tests of endogeneity

The prior literature raises the concern of endogeneity in governance studies (Hermalin and Weisbach, 2003; Wintoki et al., 2012) and our study is no exception. Wintoki et al. (2012) recognised three types of endogeneity in the corporate governance–performance relationship and existence of at least one source of potential endogeneity may generate biased estimates and may lead to inappropriate conclusions about the relations between prestigious MDS and firm performance.

As a first step to control for endogeneity, we use a fixed-effects model to estimate parameters, which are robust to the unobservable heterogeneity that may possibly be present in the multiple directorship–performance relation. The results of fixed effects regressions (for ROA) reported in Table 10 show that prestigious MDS are positively associated with ROA, which is consistent with the results of the OLS regression. Although the negative coefficient of non-prestigious MDS is not significant in the FE regression, this result supports the core predictions. In particular, the FE regressions indicate a more significant positive relationship between prestigious MDS and ROA (Prestg. MDS coefficient is 0.13 at a 1% level of significance) compared to the results of OLS (Prestg. MDS coefficient is 0.086 at a 10% level of significance).

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | OLS | |||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Intercept | −0.137 | 0.27 | 0.034 | 0.67 |

| Prestg. MDS | 0.130 | 0.00*** | 0.086 | 0.10* |

| Non-Prestg. MDS | −0.003 | 0.89 | −0.033 | 0.08* |

| Size | 0.095 | 0.01*** | −0.020 | 0.60 |

| Age | 0.029 | 0.51 | 0.073 | 0.03** |

| Leverage | 0.168 | 0.00*** | 0.040 | 0.19 |

| HighLevg | −0.132 | 0.00*** | −0.125 | 0.07* |

| BoardSize | 0.007 | 0.47 | 0.002 | 0.83 |

| OutsideDir | −0.116 | 0.21 | 0.056 | 0.56 |

| GFC | 0.009 | 0.58 | 0.014 | 0.56 |

| Loss | −0.153 | 0.00*** | −0.234 | 0.00*** |

| Panel B: Model fits | ||

|---|---|---|

| R 2 | 0.447 | 0.183 |

| F-value | 9.51 | 14.29 |

| Prob > F | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 1,020 | 1,020 |

| Panel C: Regression diagnostics | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2D Cluster | No | Yes |

| Firm fixed effects | Yes | No |

| Industry effects | No | Yes |

| R2 is obtained from (areg Y X1 X2 …Xn, absorb (firm)) | ||

- This table presents the results of fixed effects and ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of Equation (1) for ROA at the end of the year. The two explanatory variables are Prestigious MDS and Non-Prestigious MDS. The regression models rely on p-values. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. See Table 2 for definitions of dependent, independent and control variables.

In the presence of endogeneity, the OLS and fixed-effects estimates will generate biased parameter estimates, while the dynamic GMM models would produce more consistent results (Schultz et al., 2010; Wintoki et al., 2012). However, the parameter estimates from OLS and FE specifications will be more efficient than their dynamic GMM counterparts, if the regressors are not endogenous (Koerniadi et al., 2014). Therefore, we conduct a formal test of endogeneity to establish the presence of endogeneity in the MDS–performance relationship before proceeding to dynamic GMM specifications.

The Durbin–Wu–Hausman (DWH) test for endogeneity (Durbin, 1954; Wu, 1973; Hausman, 1978) is conducted for MDS measures. The results reported in Table 11 indicate that endogeneity is a significant concern for both accounting performance measures, ROA and ROE. We therefore employ both dynamic system GMM and dynamic difference GMM panel methods of estimation for ROA.

| Ho: regressors are exogenous | ||

|---|---|---|

| ROA | ROE | |

| DWH tests | 19.69*** | 31.25*** |

| p-value | 0.011 | 0.000 |

| Degrees of freedom | 8 | 8 |

- The test is based on the accounting-based performance measures (ROA and ROE) on MDS and control variables. Instruments are the lags of differenced performance measures, MDS measures and control variables. The test statistics follow a chi-squired distribution with p degrees of freedom. p is the number of regressors tested for endogeneity. Dummy variables are treated as exogenous and hence excluded. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

In the system GMM, first-differenced variables are used as instruments for the equations in levels and the estimates are obtained using the Roodman ‘xtabond2’ module in Stata. The diagnostics tests in column 2 of Panel B in Table 12 show that the model is well fitted with statistically insignificant test statistics for both second-order autocorrelation in second differences AR(2) and Hansen J-statistics of over-identifying restrictions. The residuals in the first difference should be serially correlated AR(1) by way of construction but the residuals in the second difference should not be serially correlated AR(2). Accordingly, in column 2 of Panel B in Table 12, AR(1) is statistically significant and AR(2) is statistically insignificant. Likewise, the Hansen J-statistics of over-identifying restrictions tests the null of instrument validity and the statistically insignificant Hansen J-statistics indicate that the instruments are valid in the respective estimation. The interpretation of the GMM estimates in Panel A of Table 12 remains the same as in the main findings as reported above. The results of the dynamic difference GMM procedure are also consistent with the main findings. These findings are also consistent for all accounting performance measures.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dependent variable (ROA(t)) |

System GMM | Difference GMM | ||

| Coef. | P > z | Coef. | P > z | |

| ROA L1. | 0.541 | 0.000 | 0.348 | 0.115 |

| Prestg. MDS | 0.096 | 0.132 | 0.100 | 0.055* |

| Non-Prestg. MDS | −0.058 | 0.086* | −0.040 | 0.079* |

| Size | 0.002 | 0.983 | 0.230 | 0.489 |

| Age | 0.021 | 0.806 | −0.135 | 0.395 |

| Leverage | 0.000 | 0.997 | 0.089 | 0.300 |

| BoardSize | −0.016 | 0.740 | 0.000 | 0.963 |

| OutsideDir | 0.195 | 0.319 | −0.004 | 0.958 |

| Panel B: Model fit | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. of pooled observations | 901 | 784 |

| No. of instruments | 141 | 43 |

| No. of groups | 116 | 115 |

| Arellano-Bond for AR(1) test | −1.84* | −1.71* |

| Arellano-Bond for AR(2) test | 0.386 | −0.84 |

| Hansen J-statistics | 31.22 | 17.45 |

- This table presents the results from two-step Systems GMM and two-step difference GMM regressions of MDS of two categories on ROA at the end of the year (Equation 1). AR(1) and AR(2) are tests for no serial correlation of first-order and second-order, respectively, in the first-differenced standard errors. Hansen J-stat is the test of over-identifying restrictions. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. See Table 2 for definitions of dependent, independent and control variables.

Thus, even with direct control for endogeneity using GMM procedure, this study finds evidence that there are ‘prestige’-related differences present between MDS and that these differences influence board performance and thus the firm’s performance.

4.4 Other robustness tests

We perform several tests to check the robustness and sensitivity of the findings to provide further confidence in the quality of the results of regression analysis.

4.4.1 First-difference estimation

We employ the first-difference estimation for a regression of Δyit on Δxit to examine the implications of two categories of MDS on firm performance. The results are reported in Tables 13 and 14.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ ROA | Δ ROE | |||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.003 | 0.82 | 0.001 | 0.89 |

| Δ Prestg. MDS | 0.041 | 0.06* | 0.007 | 0.70 |

| Δ Non-Prestg. MDS | 0.014 | 0.49 | 0.018 | 0.29 |

| Δ Size | 0.139 | 0.01*** | −0.049 | 0.26 |

| Δ Age | −0.062 | 0.66 | 0.028 | 0.81 |

| Δ Leverage | −0.025 | 0.60 | −0.211 | 0.00*** |

| Δ BoardSize | −0.013 | 0.21 | −0.003 | 0.75 |

| Δ OutsideDir | 0.168 | 0.15 | 0.178 | 0.07* |

| Panel B: Model fits | ||

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R2 | 0.011 | 0.028 |

| F-value | 2.45 | 4.73 |

| Prob > F | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 901 | |

- This table presents the results of first-difference regressions for two accounting-based firm performance, ROA and ROE at the end of the year. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ Stock Return | Δ Tobin's Q | |||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.024 | 0.41 | 0.031 | 0.01*** |

| Δ Prestg. MDS | 0.157 | 0.00*** | 0.047 | 0.03** |

| Δ Non-Prestg. MDS | −0.060 | 0.20 | −0.009 | 0.62 |

| Δ Size | −0.471 | 0.00*** | −1.052 | 0.00*** |

| Δ Age | 0.083 | 0.82 | −0.302 | 0.04** |

| Δ Leverage | −0.154 | 0.17 | 0.233 | 0.00*** |

| Δ Beta | −0.017 | 0.39 | −0.013 | 0.13 |

| Δ B2M | −0.101 | 0.00*** | −0.039 | 0.00*** |

| Panel B: Model fits | ||

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R2 | 0.87 | 0.365 |

| F-value | 12.68 | 71.49 |

| Prob > F | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 859 | |

- This table presents the results of first-difference regressions for two market-based firm performance, R and Q at the end of the year. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

The coefficient estimate for ΔPrestg. MDS in the ROA regression is 0.041, which is statistically significant at 10%, while there is no significant association between firm performance and non-prestigious MDS. The results for ROE, stock return and Tobin’s Q regressions are mostly consistent with the OLS results. Thus, the results obtained from first-difference estimation are consistent with the OLS results.

4.4.2 Excluding financial firms

This study includes all the NZX listed firms of seven industry categories in the final sample to obtain results from a comprehensive database. Moreover, prestigious MDS are frequently observed among financial firms. However, many prior studies excluded financial firms from their sample because of their unique characteristics, i.e. high leverage as well as specific regulations and reporting procedures (Bhuiyan, 2010; Zakaria, 2012).

To check the robustness of key findings, we repeated our analyses to examine the association between firm performance and MDS of two categories excluding financial firms. The regression results of MDS and firm performance in the current year (reported in Tables 15 and 16) as well as future performance (not reported) are similar to those of the full sample. These results suggest that financial firms do not affect our inferences.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | ROA | |||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.020 | 0.82 | 0.104 | 0.05** |

| Prestg. MDS | 0.095 | 0.10* | 0.050 | 0.06* |

| Non-Prestg. MDS | −0.039 | 0.06* | −0.018 | 0.12 |

| Size | −0.015 | 0.73 | −0.014 | 0.55 |

| Age | 0.084 | 0.01*** | 0.058 | 0.01*** |

| Leverage | 0.040 | 0.21 | 0.003 | 0.81 |

| HighLevg | −0.104 | 0.20 | −0.119 | 0.08* |

| BoardSize | 0.002 | 0.81 | 0.008 | 0.18 |

| OutsideDir | 0.044 | 0.66 | −0.092 | 0.09* |

| GFC | 0.015 | 0.59 | −0.020 | 0.07* |

| Loss | −0.238 | 0.00*** | −0.279 | 0.00*** |

| Service | −0.016 | 0.52 | 0.030 | 0.12 |

| Investments | 0.076 | 0.34 | −0.013 | 0.73 |

| Property | −0.016 | 0.67 | 0.005 | 0.79 |

| Energy | −0.113 | 0.01*** | −0.067 | 0.03** |

| Primary | −0.060 | 0.05** | −0.036 | 0.10 |

| Panel B: Model fits | ||

|---|---|---|

| R 2 | 0.189 | 0.461 |

| F-Value | 15.07 | 29.49 |

| Prob > F | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 930 | |

| Panel C: Regression diagnostics | |

|---|---|

| AVIF (max) | 1.66 (3.06) |

| 2D cluster SE | ID – 116 and Year − 10 |

| Panel D: Wald test | ||

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient comparison (F stat) | ||

| Prestg. MDS = Non-Prestg. MDS | 3.52* | 3.51* |

- This table presents the results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of Equation (1), excluding finance industry observations, for two accounting-based firm performance measures ROA and ROE at the end of the year. The two explanatory variables are Prestigious MDS and Non-Prestigious MDS. The regression models rely on p-values that account for two-dimensional clusters, by both panels (i.e., by firms (i) and time (t)). AVIF is the average ‘variance inflation factor’, which indicates the degree of collinearity problem among the regressors. The Wald (1943) test is used to assess the difference between coefficients of the respective estimates. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. See Table 2 for definitions of dependent, independent and control variables.

| Panel A: Explanatory variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stock Return (R) | Tobin’s Q (T) | |||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.029 | 0.72 | 2.094 | 0.00*** |

| Prestg. MDS | 0.107 | 0.02** | 0.161 | 0.02** |

| Non-Prestg. MDS | 0.005 | 0.80 | 0.078 | 0.12 |

| Size | −0.061 | 0.03** | −0.360 | 0.00*** |

| Age | 0.139 | 0.00*** | −0.076 | 0.44 |

| Leverage | 0.024 | 0.29 | 0.315 | 0.00*** |

| Beta | 0.001 | 0.95 | 0.035 | 0.06* |

| B2M | −0.081 | 0.00*** | −0.066 | 0.12 |

| Service | 0.151 | 0.00*** | 0.007 | 0.95 |

| Investments | 0.058 | 0.33 | −0.124 | 0.39 |

| Property | 0.102 | 0.00*** | −0.197 | 0.13 |

| Energy | −0.016 | 0.73 | −0.041 | 0.73 |

| Primary | 0.061 | 0.23 | −0.083 | 0.60 |

| Panel B: Model fits | ||

|---|---|---|

| R 2 | 0.132 | 0.353 |

| F-Value | 8.17 | 26.32 |

| Prob > F | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. of pooled observations | 883 | 887 |

| Panel C: Regression diagnostics | ||

|---|---|---|

| AVIF (max) | 1.48 | 1.49 |

| 2D cluster SE | ID – 116 and Year − 10 | |

| Panel D: Wald test | ||

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient comparison (F stat) | ||

| Prestg. MDS = Non- Prestg. MDS | 2.89* | 0.8 |

- This table presents the results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of Equation (2), excluding finance industry observations, for two market-based firm performance mesaures, Stock Return and Tobin’s Q at the end of the year. The two explanatory variables are Prestigious MDS and Non-Prestigious MDS. The regression models rely on p-values that account for two-dimensional clusters, by both panels (i.e., by firms (i) and time (t)). AVIF is the average ‘variance inflation factor’, which indicates the degree of collinearity problem among the regressors. The Wald (1943) test is used to assess the difference between coefficients of the respective estimates. *, **, *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. See Table 2 for definitions of dependent, independent and control variables.

4.4.3 Alternative measures of variables

The robustness of key findings is tested with alternative measures of dependent variables, one of these being the profit margin (Margin). The estimated coefficient on prestigious MDS is positive, (0.219), while the coefficient on non-prestigious MDS is negative (0.105) and both are statistically significant at 5% (not reported). The results suggest that prestigious MDS on the board are positively associated with firm profitability, and that this relationship is negative for non-prestigious MDS. Regarding future profitability, similar results (not reported) have been obtained. The results are therefore consistent with those for key measures of firms’ accounting performance.

In addition, regressions are repeated using untransformed (raw value) numbers of MDS as well as alternative transformation techniques, such as taking logarithms of MDS. The results (not reported) are consistent with the key results for both cases.

5 Conclusion

Using data of New Zealand listed companies from 2005 to 2014, we find in favour of our core prediction that New Zealand firms benefit from the presence of ‘prestigious’ multiple directorships (MDS) on the corporate boards. Regarding non-prestigious MDS, firm accounting performance (measured by ROA and ROE) is found to be negatively associated with non-prestigious MDS, suggesting there is no significant relationship between non-prestigious MDS and market performance (measured by stock return and Tobin’s Q). The results are robust for both categories of MDS to long-term firm performance measures, alternative firm performance measures as well as using different empirical settings.

A limitation of the study may be the extent to which data from unlisted New Zealand companies are not included. We conclude, however, that, because their involvement would be even at a lower level of complexity or global engagement than the current non-prestigious board services, that including them would not significantly alter our results. Hence, we do not believe this would have an effect on our conclusions. In fact, given the significance and direction of our findings, we believe it is more likely that their inclusion would strengthen the results we have already obtained.

These findings thus support the contention that ‘prestigious’ directors create value for New Zealand firms, which is consistent with those prior studies that provide evidence on the differential effects between different categories of MDS on firms’ outcomes (Certo et al., 2001; Loderer and Peyer, 2002; Certo, 2003; Gupta et al., 2008; Clements et al., 2015a,b). Resource dependency principles offer an explanation for this phenomenon in explaining that ‘prestigious’ directors’ knowledge of complex business transactions, their contacts and global connectivity, their experience with monitoring and strategy and their own personal reputation comprise important resources for these organisations. Such attributes may also enhance their firms’ performance due to the collaborative and symbiotic nature of relationships formed from these associations.

This is a valuable finding and particularly so for organisations which operate in relatively isolated settings – such as New Zealand – where ‘prestigious’ multiple directors may comprise important characteristics to overcome the challenges inherent with distant markets. The resource dependency concept of collaboration suggests that ‘prestigious’ directors may nurture networks that are important to achieving goals as to global trade and negotiation. The findings thus have policy implications for those larger, albeit more isolated, economies as well as for individual businesses.

A major contribution of the study is in introducing a new avenue of research into corporate governance. While the literature has focused on the implications of MDS by considering individual directorships, their ‘busyness’ or their interlocking nature, there is little knowledge about distinctions that may ensue from different types of multiple directorships. We also contribute to the literature by using a rich set of contemporaneous data, which adds to the relevance of this study.