Does managerial ownership influence corporate social responsibility (CSR)? The role of economic policy uncertainty

Abstract

To explore the drivers of corporate social responsibility (CSR), we investigate how managerial ownership influences CSR in the presence of economic policy uncertainty. Our results demonstrate that, when facing more economic policy uncertainty (EPU), firms with larger managerial ownership invest significantly more in CSR. This is in agreement with the risk mitigation hypothesis, where CSR offers insurance-like protection against adverse events. When economic policy uncertainty is not considered, however, we find that managers with higher ownership stakes invest significantly less in CSR, suggesting that CSR is driven by the agency conflict. As managers own more equity, they are subject to greater costs of CSR. Additional analyses confirm the results, including dynamic GMM, propensity score matching and instrumental-variable analysis.

1 Introduction

There has been an intense debate over the motivation behind corporate social responsibility (CSR). CSR may be motivated by the agency conflict, where managers overinvest in CSR to gain personal benefits at the expense of shareholders. This notion is generally referred to as ‘the overinvestment/agency cost hypothesis’ (Barnea and Rubin, 2010; Chintrakarn et al., 2016; Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn, 2019). On the contrary, it can be argued that CSR investments are made to reduce risk (McGuire et al., 1988; Starks, 2009). In particular, CSR activities generate a form of goodwill (or moral capital) for the company that acts as ‘insurance-like’ protection when adverse events occur (Godfrey, 2005; Gardberg and Fombrun, 2006; Godfrey et al., 2009; Jiraporn et al., 2014). The risk-reducing effect is advantageous to the firm and also ultimately to stockholders. This view is commonly labelled ‘the risk mitigation hypothesis’.

There are several notable recent studies on CSR motivation. Cheung et al. (2016) show that more socially responsible companies tend to pay higher dividends. Al-Hadi et al. (2019) explore the impact of CSR on corporate financial distress and find that CSR helps mitigate financial distress. Moreover, the beneficial effect of CSR on financial distress is significantly stronger for mature companies. Tran and O’Sullivan (2019) report that firms with stronger CSR are significantly less subject to Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) enforcement actions for financial misstatements. They also demonstrate that more socially responsible firms are less inclined to commit financial misstatements and that the reputational effect of CSR lowers the probability of SEC enforcement actions.

In spite of a substantial amount of research on CSR, the motivation behind CSR has remained surprisingly ambiguous, with mixed empirical evidence. In this study, we add to the debate on the motivation behind CSR by investigating the role of economic policy uncertainty (EPU). Based on agency theory, this study examines the effect of managerial ownership on CSR and how this effect may be altered by economic policy uncertainty. One important approach to alleviate agency problems is for managers to hold equity ownership. In doing so, managers are likely to be less inclined to pursue activities that may have adverse effects on shareholders’ wealth, as they would also suffer the consequences of such activities. Consequently, managerial equity ownership serves to align the interests of managers and stockholders. To the extent that CSR is motivated by agency conflicts and is not beneficial to the firm, managers are expected to reduce investments in CSR as their ownership rises. In contrast, to the extent that CSR investments are made to alleviate firm risk, ultimately benefiting shareholders, managers with larger ownership would be motivated to invest more in CSR, especially when firms experience economic uncertainty.

Although there is a range of studies investigating the effect of managerial ownership on CSR, this article is the first to explore the role of EPU and how it may influence the effect of managerial equity ownership on CSR. EPU is found to reduce corporate investments significantly (Julio and Yook, 2012; Gulen and Ion, 2016). We hypothesise that managers may not view CSR the same way in the presence of EPU. Managers may expropriate from shareholders through unnecessary CSR investments that boost their personal benefits at the expense of stockholders.1 The consequences of such expropriation may not be obvious during more stable times with plentiful resources. However, in the presence of EPU, firm performance is much less predictable and resources much more constrained. As a result, managers may be less motivated to expropriate. More importantly, according to the risk mitigation hypothesis, when uncertainty rises, managers can reduce the risk posed by economic uncertainty by engaging in more CSR. Therefore, we hypothesise that the motivation behind CSR may be influenced by the extent of economic uncertainty experienced by the firm.

Drawing on over 10,000 firm-year observations covering a sample period of 17 years, the results demonstrate that the motivation behind CSR is significantly influenced by EPU. To capture the degree of EPU, we employ an index recently developed by Baker et al. (2016) that has been extensively adopted in the recent literature. For managerial ownership, Bhagat and Bolton (2013) highly encourage using dollar managerial ownership because it is intuitive and suffers less from measurement error. Hence, our measure of managerial (or executive) ownership is the value of equity ownership (in dollars) held by the top-five company executives.2

Our empirical results show that larger managerial equity ownership reduces CSR engagement substantially. When managers hold a higher proportion of equity ownership, they are also exposed to increased CSR costs, leading to decreased CSR engagement. Crucially, nevertheless, in the presence of EPU, the negative effect of managerial ownership on CSR disappears. In fact, as EPU intensifies, larger managerial equity ownership leads to higher investments in CSR. Our results imply that during normal times, CSR investments are probably motivated by agency problems, in line with the findings of recent studies (Barnea and Rubin, 2010; Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn, 2019). However, as economic uncertainty rises, firm risk increases. As a result, managers engage more in CSR during uncertain times to reduce firm risk, in accordance with the prediction of the risk mitigation hypothesis. Because the risk-reducing effect of CSR is favourable to the firm and shareholders, in the presence of economic uncertainty, managers with higher ownership stakes are motivated to invest significantly more in CSR.

To demonstrate that our results are robust, we conduct several robustness checks, including fixed effects as well as random effects models, dynamic generalised method of moments (GMM), propensity score matching (PSM), and instrumental variable (IV) analysis. These robustness tests suggest that our results are not likely affected by endogeneity. Finally, we investigate each CSR category individually, finding that, during uncertain times, firms invest significantly more in those CSR activities related to the environment and diversity, implying that these activities have the most risk-mitigating potential.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 explains the research methodology, Section 3 presents and discusses the results, and Section 4 offers the conclusions.

2 Sample and data description

The data on EPU are from Baker et al. (2016), who develop the economic policy uncertainty index (EPU index). This index is a weighted average with three components: news events, tax code changes and monetary and fiscal policy forecast dispersions. The KLD database is used to source the CSR ratings. The ExecuComp and Compustat databases provide data for the calculation of managerial ownership (the total dollar equity ownership held by the top-five company executives) and firm characteristics. The final sample comprises 10,303 firm-year observations covering the sample period from 1995 to 2012.

Our variable for managerial ownership is the natural log of (1 + dollar value of managerial ownership).3 We add one to avoid having zero in the log function. The KLD score is used to capture the degree of CSR in line with the literature. The KLD score comprises both strength and concern ratings for community, diversity, corporate governance, employee relations, environment, human rights and product. Exclusionary screen categories (concern ratings only) include alcohol, gambling, firearms, military, tobacco and nuclear power. We do not include the exclusionary screen as part of the total CSR score. We also exclude the corporate governance category from consideration as managerial ownership can be considered a governance mechanism. The total of the strengths minus the concerns is the composite CSR score (Goss and Roberts, 2011; Jiraporn et al., 2014).

Based on the CSR literature (Barnea and Rubin, 2010; El Ghoul et al., 2011; Goss and Roberts, 2011; Chintrakarn et al., 2015; 2016; Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn, 2019), we include several control variables: profitability (EBIT/total assets), firm size (natural log of total assets), leverage (total debt/total assets), capital investments (capital expenditures/total assets), intangible assets (advertising and R&D/total assets), cash holdings (cash holdings/total assets), asset tangibility (fixed assets/total assets), dividends (dividends/total assets), and discretionary spending (selling, general, and administrative expenses (SG&A)/total assets). To control for corporate governance, we also include board size and board independence (the percentage of independent directors on the board). Additionally, we include firm-fixed effects, which account for any characteristics that remain constant over time. Finally, we include year fixed effects to account for variation over time.

Based on the CSR literature (Barnea and Rubin, 2010; El Ghoul et al., 2011; Goss and Roberts, 2011; Chintrakarn et al., 2016; 2017; Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn, 2019), some of the control variables can be expected to have the following effects on CSR. For instance, large and more profitable firms are likely to invest more in CSR; more cash holdings should be associated with more CSR investments; and more stable firms that pay dividends tend to invest more in CSR.

Table 1 presents the summary statistics. The EPU Index averages 114.656. The CSR score averages 0.137, indicating that the firms in our sample predominantly exhibit a higher level of CSR strengths compared to concerns. The dollar value of managerial ownership averages $187,749. On average, 73.814 percent of the directors are independent. The average board has 9.521 directors. Table 1 also shows the descriptive statistics for several firm characteristics.

| Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | 25th | 75th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Policy Uncertainty Index (EPU) | 114.656 | 110.126 | 35.193 | 80.517 | 143.946 |

| CSR Score | 0.137 | 0.000 | 2.381 | −1.000 | 1.000 |

| Managerial Ownership (dollars) | 187,749 | 42,296 | 1,917,327 | 16,900 | 101,526 |

| % Independent Directors | 73.814 | 76.923 | 14.443 | 66.667 | 85.714 |

| Board Size | 9.521 | 9.000 | 2.530 | 8.000 | 11.000 |

| Total Assets | 15,957 | 2,628 | 82628.91 | 896 | 8305 |

| EBIT/Total Assets | 0.101 | 0.093 | 0.088 | 0.053 | 0.143 |

| Capital Expenditures/Total Assets | 0.048 | 0.034 | 0.052 | 0.016 | 0.062 |

| Total Debt/Total Assets | 0.207 | 0.197 | 0.166 | 0.060 | 0.316 |

| R&D/Total Assets | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.048 | 0.000 | 0.031 |

| Advertising Expenses/Total Assets | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.033 | 0.000 | 0.006 |

| Cash Holdings/Total Assets | 0.142 | 0.079 | 0.160 | 0.027 | 0.203 |

| Dividends/Total Assets | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.019 |

| Fixed Assets/Total Assets | 0.515 | 0.400 | 0.369 | 0.223 | 0.760 |

| SG&A Expenses/Total Assets | 0.226 | 0.191 | 0.169 | 0.114 | 0.293 |

- The Economic Policy Uncertainty Index is defined in Baker et al. (2016). The CSR Score is the number of CSR strength ratings minus the number of CSR concern ratings. Managerial ownership is defined as Ln (1 + dollar value of managerial ownership), where the dollar value of managerial ownership held by the top-five managers is used. SG&A are the selling, administrative and general (SG&A) expenses.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline regression results

The regression results are presented in Table 2. Model 1 is an OLS regression with year and industry fixed effects. Managerial ownership carries a negative and significant coefficient, suggesting that CSR is motivated by the agency conflict. When managers own more equity, they bear greater costs of CSR and therefore significantly reduce CSR investments. This is consistent with the overinvestment/agency cost hypothesis. More crucially, however, there is a positive and significant coefficient on the variable interacting managerial ownership and EPU. As EPU intensifies, larger managerial ownership leads to significantly more CSR investments. This is consistent with the risk mitigation view, where CSR can be employed as a useful tool to safeguard the firm against economic uncertainty. This risk-reducing property of CSR is beneficial to the firm and also ultimately to shareholders. As a result, managers with larger equity ownership are more motivated to invest in CSR in the presence of economic uncertainty. Thus, the evidence supports the risk mitigation hypothesis.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | Fixed effects | Random effects | Dynamic GMM | Propensity score matching | |

| CSR | CSR | CSR | CSR | CSR | |

| EPU Index × Managerial Ownership | 0.001*** | 0.002*** | 0.002*** | 0.001** | −0.002*** |

| (2.809) | (7.702) | (6.871) | (2.461) | (−3.621) | |

| Managerial Ownership | −0.115** | −0.192*** | −0.167*** | −0.186*** | 0.154*** |

| (−2.392) | (−6.617) | (−5.847) | (−2.912) | (3.593) | |

| EPU Index | −0.004 | 0.001 | −0.007* | −0.007 | 0.050*** |

| (−0.815) | (0.198) | (−1.885) | (−1.048) | (8.381) | |

| % Independent Directors | 0.006** | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.006** |

| (2.010) | (−1.207) | (0.623) | (0.444) | (−2.102) | |

| Ln (Board Size) | 0.870*** | 0.579*** | 0.622*** | 0.223 | 0.843*** |

| (3.977) | (3.881) | (4.791) | (1.030) | (3.902) | |

| Ln (Total Assets) | 0.466*** | −0.423*** | 0.332*** | −0.317** | −0.324*** |

| (8.894) | (−6.151) | (10.786) | (−2.311) | (−3.265) | |

| EBIT/Total Assets | 1.768*** | 0.882*** | 0.822*** | −0.173 | 0.355 |

| (4.001) | (2.880) | (3.007) | (−0.405) | (0.771) | |

| Capital Expenditures/Total Assets | 2.217* | −0.677 | −0.325 | −0.829 | 0.041 |

| (1.801) | (−1.059) | (−0.547) | (−0.977) | (0.041) | |

| Total Debt/Total Assets | −0.428 | 0.616*** | 0.267 | 0.288 | 0.804*** |

| (−1.398) | (3.044) | (1.536) | (0.926) | (2.692) | |

| R&D/Total Assets | 4.538*** | −1.535* | 1.412* | 0.241 | −0.561 |

| (3.555) | (−1.671) | (1.946) | (0.248) | (−0.505) | |

| Advertising Expenses/Total Assets | 1.704 | −1.207 | −0.645 | 0.224 | −4.361** |

| (0.996) | (−1.020) | (−0.691) | (0.134) | (−2.011) | |

| Cash Holdings/Total Assets | 1.080*** | −0.016 | 0.829*** | −0.639* | 0.000 |

| (3.586) | (−0.065) | (4.272) | (−1.942) | (0.001) | |

| Dividends/Total Assets | 2.734* | 0.951 | 1.782** | −2.192** | −0.198 |

| (1.902) | (1.033) | (2.072) | (−2.219) | (−0.113) | |

| Fixed Assets/Total Assets | −0.026 | −0.157 | 0.237* | −0.320 | −0.109 |

| (−0.128) | (−0.805) | (1.814) | (−0.966) | (−0.373) | |

| SG&A Expenses/Total Assets | 1.972*** | −1.320*** | 0.969*** | −0.850 | −2.056*** |

| (3.994) | (−3.298) | (3.597) | (−1.336) | (−3.212) | |

| Constant | −8.653*** | 2.411*** | −5.836*** | 3.519** | −2.824*** |

| (−8.306) | (3.306) | (−4.837) | (2.541) | (−2.709) | |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm-fixed effects | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 10,303 | 10,303 | 10,303 | 5,961 | 5,152 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.224 | 0.642 | 0.743 |

- The Economic Policy Uncertainty Index is defined in Baker et al. (2016). The CSR Score is the number of CSR strength ratings minus the number of CSR concern ratings. Managerial ownership is defined as Ln (1 + dollar value of managerial ownership), where the dollar value of managerial ownership held by the top-five managers is used. SG&A are the selling, administrative and general (SG&A) expenses. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses. *, **, *** denote statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively.

To mitigate the omitted-variable bias, a firm-fixed-effects regression analysis is employed in Model 1 in order to control for any time-invariant unobservable characteristics. Similarly, the managerial ownership coefficient is significantly negative, while the coefficient of the interaction term is positive. Because the firm-fixed-effects regression produces a similar result, it does not appear that the result is unduly influenced by omitted-variable bias. As a further robustness analysis, a random-effects regression is implemented in Model 3. The results remain consistent.

For further confirmation, a dynamic GMM panel estimator is used to take advantage of the dynamic relationships in the explanatory variables. In order to remove any potential bias from time-invariant unobserved characteristics, the variables are first-differenced. Next, a GMM regression is implemented using lagged values of the explanatory variables as instruments for the contemporaneous explanatory variables, as this method is less prone to omitted-variable bias. The dynamic GMM analysis (Model 4) remains consistent with our main findings.

Finally, as an additional robustness check, we conduct propensity score matching (PSM). We divide the sample into four quartiles using managerial ownership. We consider the top quartile with the largest managerial ownership the treatment group. For each firm in the treatment group, a firm is identified from the other three quartiles that is most similar based on 12 firm characteristics, i.e. the 12 control variables in the regression analysis. Therefore, our treatment and control groups are nearly identical, except for one aspect, i.e. managerial ownership. Then, we run a firm-fixed-effects regression using the PSM sample (Model 5). The results are in agreement with our main findings.

3.2 Additional robustness checks

Managerial ownership is notoriously endogenous. The empirical tests described above already address endogeneity to some extent. For instance, the firm-fixed-effects analysis and the dynamic GMM analysis alleviate the omitted-variable bias. In any event, we perform additional analysis to further mitigate endogeneity. We employ an IV analysis. We select as our instrument the value of managerial ownership in the earliest year for each firm. The idea is that managerial ownership in the earliest year could not have been influenced by CSR in any of the subsequent years, making reverse causality much less likely.

Table 3 shows the results. In Model 1, we regress managerial ownership on the value of managerial ownership in the earliest year as well as the control variables. This is the first-stage regression. As expected, the coefficient of managerial ownership in the earliest year is significantly positive. In Model 2, CSR is regressed against managerial ownership (in this case, the value of managerial ownership in the earliest year for each firm). The interaction variable between EPU and managerial ownership is significantly positive. Thus, the result of our IV analysis confirms our main findings. In the presence of EPU, managers with larger equity invest significantly more in CSR, probably to decrease risk, consistent with the risk mitigation hypothesis.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managerial Ownership | CSR | CSR | CSR | |

| Managerial Ownership (Earliest Year) | 0.307*** | |||

| (12.824) | ||||

| EPU × Managerial Ownership (Instrumented) | 0.004*** | 0.003*** | 0.003** | |

| (5.923) | (3.211) | (1.998) | ||

| Managerial Ownership (Instrumented) | −0.400*** | −0.219 | −0.421 | |

| (−3.398) | (−1.643) | (−1.564) | ||

| EPU | 0.001 | −0.036*** | −0.016 | −0.015 |

| (0.587) | (−4.438) | (−1.600) | (−0.825) | |

| % of Independent Directors | −0.008*** | 0.006** | 0.004 | 0.015* |

| (−4.198) | (2.096) | (0.824) | (1.783) | |

| Ln (Board Size) | −0.081 | 0.890*** | 0.858** | 1.659*** |

| (−0.518) | (4.098) | (2.573) | (2.905) | |

| Ln (Total Assets) | 0.428*** | 0.421*** | 0.459*** | 0.647*** |

| (16.630) | (5.866) | (5.145) | (5.080) | |

| EBIT/Total Assets | 2.884*** | 1.522*** | 1.769*** | 1.589 |

| (7.840) | (2.940) | (2.829) | (1.127) | |

| Capital Expenditures/Total Assets | 3.158*** | 1.912 | 0.738 | 0.920 |

| (3.960) | (1.509) | (0.396) | (0.268) | |

| Total Debt/Total Assets | −0.438** | −0.408 | −0.829** | −0.127 |

| (−2.232) | (−1.335) | (−1.966) | (−0.189) | |

| R&D/Total Assets | 0.950 | 4.493*** | 4.265** | 9.686*** |

| (1.290) | (3.488) | (2.261) | (2.918) | |

| Advertising Expenses/Total Assets | 1.318* | 1.520 | 1.272 | 10.107* |

| (1.665) | (0.882) | (0.558) | (1.855) | |

| Cash Holdings/Total Assets | 0.466** | 0.971*** | 1.021** | 1.436 |

| (2.202) | (3.100) | (2.408) | (1.635) | |

| Dividends/Total Assets | −4.135*** | 3.084** | 3.778** | 13.492*** |

| (−2.689) | (2.062) | (1.967) | (2.986) | |

| Fixed Assets/Total Assets | −0.373*** | 0.006 | 0.019 | −0.019 |

| (−3.211) | (0.030) | (0.065) | (−0.040) | |

| SG&A Expenses/Total Assets | 0.201 | 1.949*** | 2.200*** | 2.660** |

| (0.926) | (3.928) | (3.565) | (2.327) | |

| Constant | 4.122*** | −5.413*** | −8.356*** | −10.193*** |

| (7.454) | (−3.901) | (−5.086) | (−2.956) | |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 10,303 | 10,303 | 5,236 | 2,265 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.335 | 0.228 | 0.262 | 0.344 |

- The Economic Policy Uncertainty Index is defined in Baker et al. (2016). The CSR Score is the number of CSR strength ratings minus the number of CSR concern ratings. Managerial ownership is defined as Ln (1 + dollar value of managerial ownership), where the dollar value of managerial ownership held by the top-five managers is used. SG&A are the selling, administrative and general (SG&A) expenses. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses. *, **, *** denote statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively.

One possible concern about using the earliest value of managerial ownership as the instrument is that managerial ownership may be ‘sticky’, i.e., changing slowly over time. If this is the case, the value of managerial ownership in the earliest year may not vary significantly from those in subsequent years. To mitigate this concern, we calculate the standard deviation of managerial ownership within each firm. Then, we divide the sample into two subsamples using the median of the standard deviation. Firms above the median are those whose managerial ownership is less sticky, i.e. changing more over time, than those below the median. Therefore, these firms are less vulnerable to the concern regarding the stickiness of managerial ownership. We then run the second-stage regression on this subsample only in Model 3. The coefficient of the interaction variable remains significantly positive. Because we obtain a similar result, it is not likely that the stickiness of managerial ownership poses a serious problem.

Furthermore, it can be argued that the data for some firms may be available for only a few years, i.e. only a short time series of the data are available. As a result, the value of managerial ownership in the earliest year may not differ significantly from those in the subsequent years. This does not appear to be much of a problem as the median length of our panel data is 7 years (i.e. on average, our sample firms have data available for 7 years). In any case, to alleviate this concern, we run a second-stage regression only on those observations where the earliest value of managerial ownership is at least 7 years apart from the value of managerial ownership in any given year. Seven years should be sufficiently long for managerial ownership to change. The results of Model 3 are consistent with our main findings.

Moreover, we employ alternative instrumental variables, i.e. average managerial equity ownership of companies located in the same area. Managers of firms located close by likely have more social interactions with one another and may behave similarly. We adopt the average level of managerial ownership of companies located in the same 3-digit zip code as our instrument. Zip codes are assigned to maximise efficiency in mail delivery. Therefore, zip code assignments are likely exogenous, unrelated to corporate policies and outcomes (Jiraporn et al., 2014; Chintrakarn et al., 2015; 2017). Using this instrumental variable, we obtain consistent results. As robustness checks, we use as our alternative instruments the averages of managerial ownership of firms located in the same phone area code and in the same city. All the results are consistent (results not shown but available upon request).

In addition, to further show that our results are not susceptible to the omitted-variable bias, we exploit the insights in Oster (2019). Oster (2019) invents a method to test coefficient stability, i.e. how vulnerable the estimated coefficients are to the possible effect of the unobservables. We employ Oster’s (2019) method for testing the coefficient stability in the fixed effects regression in Model 2 of Table 2. If we attribute the estimated coefficient of the interaction term exclusively to the observables, the coefficient is 0.002. On the contrary, if we assume that the unobservables have an effect as strong as the observables, the coefficient of the interaction term would be 0.0005, much smaller, but not zero. Thus, our estimated coefficient for the interaction term is stable. Even if the effect of the unobservables were as strong as the effect of the observables, it would not invalidate our results.

So far, we have addressed endogeneity with respect to managerial ownership. It can be argued that endogeneity may be attributed to EPU as well. To address this issue, we run additional analysis as follows. First, we replace the EPU index with its tax-related component. This specific component of the index represents the discounted value of the revenue effects on all tax provisions set to expire during the next ten years. Because the expirations of the tax provisions were determined far ahead of time, this portion of the uncertainty is more likely exogenous. The regression results are shown in Table 4. In Model 1, we replace EPU with its tax-related component. The interaction term coefficient continues to be both positive and significant. Thus, the result remains similar, even when the more likely exogenous component of the index is used.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | EPU | CSR | CSR | |

| EPU (Taxes) × Managerial Ownership | 0.000*** | |||

| (11.470) | ||||

| EPU (Taxes) | −0.001*** | |||

| (−4.475) | ||||

| Partisan Conflict Index (Azzimonti, 2018) | 0.962*** | |||

| (80.972) | ||||

| EPU (Instrumented) × Managerial Ownership | 0.003*** | 0.003*** | ||

| (9.694) | (9.909) | |||

| Managerial Ownership | −0.048*** | −1.431*** | −0.223*** | −0.251*** |

| (−4.061) | (−9.119) | (−6.445) | (−7.467) | |

| EPU (Instrumented) | 0.020*** | −0.003 | ||

| (3.126) | (−0.416) | |||

| % of Independent Directors | −0.002 | 0.393*** | −0.021*** | −0.009*** |

| (−1.258) | (15.008) | (−6.797) | (−3.117) | |

| Ln (Board Size) | 0.586*** | 19.089*** | −0.409** | 0.164 |

| (3.946) | (8.602) | (−2.295) | (1.039) | |

| Ln (Total Assets) | −0.477*** | 13.679*** | −1.089*** | −0.088 |

| (−6.934) | (16.197) | (−9.291) | (−1.109) | |

| EBIT/Total Assets | 0.782** | −55.671*** | 3.684*** | 2.250*** |

| (2.565) | (−12.036) | (8.420) | (5.630) | |

| Capital Expenditures/Total Assets | −0.570 | −57.766*** | 2.182*** | 0.646 |

| (−0.895) | (−6.049) | (2.975) | (0.984) | |

| Total Debt/Total Assets | 0.561*** | 14.517*** | −0.136 | −0.251 |

| (2.781) | (4.756) | (−0.625) | (−1.375) | |

| R&D/Total Assets | −1.467 | 39.522*** | −3.542*** | 0.936 |

| (−1.603) | (2.824) | (−3.723) | (1.335) | |

| Advertising Expenses/Total Assets | −1.095 | −21.274 | −0.291 | 0.270 |

| (−0.929) | (−1.177) | (−0.246) | (0.294) | |

| Cash Holdings/Total Assets | −0.065 | 22.494*** | −1.056*** | 0.308 |

| (−0.275) | (6.301) | (−3.805) | (1.356) | |

| Dividends/Total Assets | 0.817 | −22.381 | 2.055** | 1.987** |

| (0.892) | (−1.601) | (2.228) | (2.309) | |

| Fixed Assets/Total Assets | −0.191 | 34.497*** | −1.865*** | −1.040*** |

| (−0.988) | (11.858) | (−6.536) | (−4.921) | |

| SG&A Expenses/Total Assets | −1.386*** | 28.909*** | −2.780*** | 0.382 |

| (−3.477) | (4.772) | (−6.345) | (1.375) | |

| Constant | 3.029*** | −169.967*** | 8.818*** | 0.767 |

| (4.538) | (−19.944) | (9.705) | (1.308) | |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Firm-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Observations | 10,303 | 10,303 | 10,303 | 10,303 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.644 | 0.616 | 0.643 |

- The Economic Policy Uncertainty Index is defined in Baker et al. (2016). The CSR Score is the number of CSR strength ratings minus the number of CSR concern ratings. Managerial ownership is defined as Ln (1 + dollar value of managerial ownership), where the dollar value of managerial ownership held by the top-five managers is used. SG&A are the selling, administrative and general (SG&A) expenses. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses. *, **, *** denote statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively.

Second, following Chan et al. (2017) and Bonaime et al. (2018), we employ the Partisan Conflict Index (PCI) developed by Azzimonti (2018) as our instrumental variable. This index reflects the degree of political disagreement among US politicians at the federal level by conducting keyword searches on major newspapers. In Model 2 of Table 4, we regress EPU on the PCI and the control variables (the first stage of the regression). The PCI coefficient is positive and significant, as expected. Model 3 is the second-stage firm-fixed-effects regression, where CSR is regressed against the term interacting managerial ownership and EPU (as instrumented from the first stage). The coefficient variable still carries a positive and significant coefficient. As a robustness check, a random-effects regression is also employed (Model 4). The interaction term coefficient remains positive and significant.

In conclusion, after subjecting the results to several robustness tests that alleviate endogeneity, we continue to find that higher managerial ownership leads to more CSR investments in the presence of EPU. Admittedly, it is nearly impossible to rule out endogeneity entirely. However, our various robustness tests suggest that our results are unlikely driven by endogeneity.

3.3 Analysis of the CSR categories

So far, we have investigated the impact of managerial ownership on overall CSR in the presence of EPU. In this section, we further examine each CSR category individually. Our CSR score consists of the following dimensions: community, diversity, employee, environment, human rights and product. The results are shown in Table 5. The coefficients of managerial ownership are all negative and significant, except for the employee and product categories. This is consistent with previous findings, where managers decrease CSR investments as their ownership rises (Barnea and Rubin, 2010; Chintrakarn et al., 2016; Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn, 2019). This is the case for most CSR categories. The results suggest that the CSR activities associated with employees and products are not driven by agency conflicts, whereas the other categories are likely to be affected by such conflicts.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community | Diversity | Employee | Environment | Human rights | Product | |

| EPU Index × Managerial Ownership | 0.000*** | 0.001*** | −0.000*** | 0.002*** | 0.000*** | 0.000** |

| (4.651) | (7.785) | (−3.580) | (13.238) | (5.475) | (2.291) | |

| Managerial Ownership | −0.034*** | −0.111*** | 0.045*** | −0.163*** | −0.020*** | −0.002 |

| (−4.020) | (−7.194) | (3.222) | (−12.455) | (−4.445) | (−0.173) | |

| EPU Index | −0.004*** | −0.004** | 0.013*** | −0.007*** | −0.002*** | −0.001 |

| (−4.185) | (−2.195) | (7.659) | (−4.321) | (−3.888) | (−0.608) | |

| % of Independent Directors | −0.000 | 0.000 | −0.003*** | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 |

| (−0.134) | (0.365) | (−3.081) | (−0.697) | (0.433) | (−1.242) | |

| Ln (Board Size) | 0.125*** | −0.030 | 0.301*** | 0.051 | −0.013 | 0.106** |

| (2.856) | (−0.373) | (4.210) | (0.760) | (−0.564) | (2.236) | |

| Ln (Total Assets) | 0.046** | −0.022 | 0.047 | −0.359*** | −0.064*** | −0.178*** |

| (2.285) | (−0.596) | (1.435) | (−11.587) | (−6.038) | (−8.190) | |

| EBIT/Total Assets | −0.003 | 0.057 | 0.679*** | 0.186 | −0.077 | 0.030 |

| (−0.037) | (0.352) | (4.634) | (1.344) | (−1.629) | (0.309) | |

| Capital Expenditures/Total Assets | −0.403** | −0.340 | −0.036 | −0.237 | −0.060 | 0.078 |

| (−2.143) | (−0.999) | (−0.116) | (−0.819) | (−0.611) | (0.384) | |

| Total Debt/Total Assets | 0.203*** | 0.304*** | −0.023 | 0.281*** | 0.004 | −0.158** |

| (3.412) | (2.823) | (−0.236) | (3.073) | (0.139) | (−2.474) | |

| R&D/Total Assets | −0.288 | −0.273 | 0.120 | −1.058** | 0.031 | −0.270 |

| (−1.066) | (−0.558) | (0.273) | (−2.551) | (0.218) | (−0.928) | |

| Advertising Expenses/Total Assets | 0.230 | −1.196* | −0.258 | 0.678 | −0.095 | −0.432 |

| (0.663) | (−1.897) | (−0.456) | (1.268) | (−0.521) | (−1.152) | |

| Cash Holdings/Total Assets | 0.129* | 0.015 | −0.291** | −0.047 | 0.014 | −0.007 |

| (1.849) | (0.122) | (−2.552) | (−0.438) | (0.368) | (−0.089) | |

| Dividends/Total Assets | 0.738*** | 0.594 | 0.120 | 0.122 | 0.069 | −0.119 |

| (2.728) | (1.212) | (0.272) | (0.293) | (0.484) | (−0.410) | |

| Fixed Assets/Total Assets | 0.163*** | −0.069 | 0.224** | −0.383*** | −0.031 | −0.075 |

| (2.851) | (−0.667) | (2.405) | (−4.358) | (−1.021) | (−1.222) | |

| SG&A Expenses/Total Assets | 0.172 | −0.391* | −0.309 | −0.891*** | −0.179*** | −0.617*** |

| (1.460) | (−1.834) | (−1.612) | (−4.932) | (−2.897) | (−4.869) | |

| Constant | −0.130 | 0.524 | −1.935*** | 3.654*** | 0.807*** | 1.302*** |

| (−0.608) | (1.349) | (−5.548) | (11.104) | (7.162) | (5.644) | |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 10,303 | 10,303 | 10,303 | 10,303 | 10,303 | 10,303 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.562 | 0.743 | 0.486 | 0.556 | 0.452 | 0.601 |

- The Economic Policy Uncertainty Index is defined in Baker et al. (2016). The CSR Score is the number of CSR strength ratings minus the number of CSR concern ratings. Managerial ownership is defined as Ln (1 + dollar value of managerial ownership), where the dollar value of managerial ownership held by the top-five managers is used. SG&A are the selling, administrative and general (SG&A) expenses. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses. *, **, *** denote statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively.

Crucially, the coefficients of the interaction variable between managerial ownership and the EPU Index are all significantly positive, except for the employee category. In the presence of EPU, managers invest significantly more in almost all CSR categories, again consistent with the previous findings. The results are in favour of the risk mitigation hypothesis, where managers invest in CSR to mitigate firm risk during uncertain times.

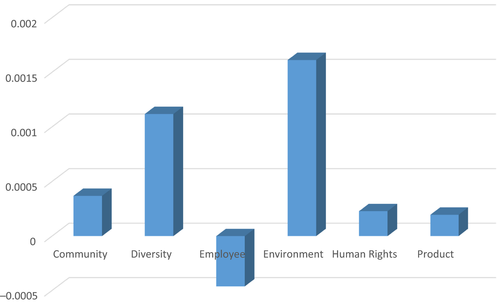

To find out which CSR activities or categories are expected to have the strongest risk-mitigating effects, we rely on the coefficients of the interaction term in Table 5 to construct a bar graph in Figure 1. In the presence of economic uncertainty, managers raise investments in the CSR activities related to the environment the most and those related to diversity the second most. It appears that these activities are believed to have the strongest risk-mitigating effects, leading to increased firm investments during economic uncertainty. On the contrary, managers reduce investments in employee-related CSR activities, suggesting that these activities probably do not mitigate firm risk.

4 Conclusion

In this paper, we concentrate on managerial ownership to explore the motives for CSR investments. Furthermore, we investigate how these motives may change in the presence of economic policy uncertainty. Our results reveal that higher managerial ownership leads to lower investments in CSR, suggesting that CSR is motivated by the agency conflict. However, in the presence of EPU, higher managerial ownership leads to significantly more CSR investments. With more uncertainty, managers engage in more CSR to reduce firm risk. Therefore, when economic uncertainty is taken into consideration, our results are consistent both with the overinvestment/agency cost hypothesis as well as the risk mitigation hypothesis. We make apposite contributions to the debate regarding the motivation behind CSR. Future studies on CSR should take into consideration the effect of EPU.

A large number of robustness checks confirm the results, suggesting that our results are unlikely affected by endogeneity either caused by reverse causality or unobserved heterogeneity. Finally, we demonstrate that during uncertain times, firms invest significantly more in the CSR activities related to the environment and diversity, suggesting that these activities have the strongest risk-mitigating potential.

References

- 1 For instance, managers may invest in corporate social responsibility to improve their personal reputation as admirable and responsible citizens or to attract media attention, although such CSR investments do not necessarily enhance shareholder wealth (Barnea and Rubin, 2010; Chintrakarn et al., 2016; Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn, 2019).

- 2 The ExecuComp database reports the data only for the top-five executives for each firm. As a consequence, we focus on the managerial ownership of the top-five executives.

- 3 It is not uncommon in the literature to apply the log function to a variable that contains large values, such as the dollar value of ownership or the dollar value of total compensation (Bhagat and Bolton, 2013; Huang et al., 2017; Dai et al., 2019; Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn, 2019). The purpose is to reduce the skewness in the distribution of the variable as well as to minimise the effect of possible outliers.