Positive spillover effect and audit quality: a study of cancelling China’s dual audit system

Abstract

The mandatory dual-audit and dual-reporting system (DADRS) for mainland Chinese firms cross-listed in Hong Kong (AH firms) was abolished in 2010. This study quantifies a positive spillover effect from Hong Kong-based auditors in the DADRS and examines whether and to what extent this affects the audit quality of AH firms. We find that AH firms exposed to a stronger positive spillover effect have higher audit quality, and the loss of this effect drives the declining audit quality of AH firms after they cancelled the DADRS. This study is among the first empirical works on this research topic.

1 Introduction

This study investigates the association between the positive spillover effect from Hong Kong-based (hereafter HK) auditors to mainland China-based (hereafter MC) auditors in the dual-audit and dual-reporting system (DADRS) and the audit quality of mainland Chinese firms cross-listed in Hong Kong (AH firms). The study exploits the official end to the mandatory DADRS in 2010 to analyse the impact of the positive spillover on audit quality of firms that kept and cancelled the DADRS. Specifically, this study answers the following research questions: (i) How should this positive spillover effect be measured? (ii) Do AH firms that kept the DADRS have higher audit quality when they are subject to a stronger positive spillover effect? (iii) Does a loss of positive spillover effect drive a decline in audit quality of AH firms that cancelled the DADRS?

This study is motivated by the increasing role of China in the Asia-Pacific economy and the institutional features unique to the Chinese audit market. With China’s rapid development and opening up in the last three to four decades, it has become a main emerging economy in the region. Research findings on China can provide insights for academics and practitioners, as it is one of the most important players in the Asia-Pacific economy (Han et al., 2018). As a result, China has attracted increasing research attention (Linnenluecke et al., 2016). Furthermore, the unique institutional features of the Chinese audit market provide researchers with an abundance of research opportunities. For example, it is more dispersed and competitive than the audit markets of western countries, such as the US (Lu and Fu, 2014; Huang et al., 2015). In mainland China, the auditing profession is under the regulation and administration of government agencies, like the Ministry of Finance (MOF) and the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC; Han et al., 2018). With the aim of making large mainland audit firms alternatives to the Big 4 audit firms, government agencies have introduced considerable structural changes and reforms to support the development of the mainland auditing profession (Chen et al., 2011). The distinct institutional and regulatory features of the Chinese market generate opportunities to investigate interesting auditing issues, like the effects of regulations and policies on audit choices or outcomes (Chang et al., 2018), and provide several natural experiment settings for researchers to examine issues that cannot be validly tested elsewhere (Linnenluecke et al., 2017). As a result, auditing in China has become one of the most popular accounting research streams in the Asia-Pacific region (Han et al., 2018). Prior studies on auditing in China have paid significant attention to exploring the determinants of audit quality, such as client importance (Chen et al., 2010), political connections (Chan et al., 2006, 2012; Liu et al., 2011; Yang, 2013), social ties (Guan et al., 2016; He et al., 2017), corporate social responsibility (Carey et al., 2017) and analyst coverage (Chen et al., 2016). Some studies have also analysed auditor independence (DeFond et al., 1999; Chan and Wu, 2011; Xiao et al., 2016), auditor choice (Wang et al., 2008) and auditors’ organisational features (Hao, 1999; Shafer, 2009; Firth et al., 2012). Moreover, data provided by the MOF and authorised databases in China enable researchers to deepen understanding of audit adjustments (Lennox et al., 2016) and individual-level auditor characteristics (Gul et al., 2013; Su and Wu, 2016; Li et al., 2017; He et al., 2018). Another distinctive feature of the Chinese market is that its institutional environment is considered to be weaker than that of developed markets, with unsound legal systems and lower levels of investor protection (Ball et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2006). A notable study on how the gap in the institutional environment between the Chinese market and developed markets affects audit quality is Ke et al.(2015). They find that Big 4 auditors assign more-experienced partners and guarantee higher audit quality for their audit clients that are cross-listed in mainland China and Hong Kong than for their clients that are listed only in mainland China. Ke et al.(2015) attribute this to a positive spillover effect from HK auditors, which operate in the stronger institutional environment of Hong Kong, to MC auditors, which operate in the weaker institutional environment of mainland China, in the DADRS.

Inspired by Ke et al.(2015), this study aims to deepen understanding of the role of this positive spillover effect in the audit quality of AH firms by exploiting the setting of the official abolition of the mandatory DADRS in 2010. According to the mandatory DADRS, an AH firm’s A-share financial statements had to be prepared based on the Chinese Accounting Standards (CAS) and audited by an MC audit firm, while its H-share financial statements had to be prepared based on the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) or Hong Kong Financial Reporting Standards (HKFRS) and audited by a HK audit firm. Two audit firms produced separate annual audit reports for the same AH firm. This unique audit system distinguished AH firms from firms listed only in mainland China. With the abolition of the mandatory DADRS, AH firms may cancel the DADRS and prepare only the A-share financial statements based on the CAS using a single approved MC auditor. Tsingtao Brewery was the first AH firm to cancel the DADRS in December 2010. By 2015, 36.17 percent of the sampled AH firms had dismissed their HK auditors (see Table 3).

Although cancelling the DADRS is aimed at improving audit efficiency and lowering audit costs of AH firms, the policy change has also raised concerns about possible impairment of their financial reporting quality. As documented in the ‘Consultation Conclusions on Acceptance of Mainland Accounting and Auditing Standards and Mainland Audit Firms for Mainland Incorporated Companies Listed in Hong Kong’ (Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEx), 2010), there are concerns that MC auditors lack the necessary knowledge and experience of Hong Kong rules and regulations, and thus, the quality of their sole audits might not be guaranteed. The loss of a positive spillover effect from HK auditors is a common explanation for the audit quality decline after the cancellation of the DADRS. This effect stems from the institutional environment gap for cross-listed AH firms (Ke et al., 2015). Specifically, the institutional environment in Hong Kong is much stronger than that in mainland China in terms of law enforcement, investor protection, and media monitoring, among other factors, which leads to higher independence and audit quality of HK auditors than that of MC auditors. Moreover, according to the rules and regulations of the AH-share market, both sets of the financial statements of an AH firm should be substantially consistent, which implies an indirect positive spillover effect from the HK auditor to the MC auditor. Since the exemplary audit work, outcomes and potential monitoring of the HK auditor influence the MC auditor (Lin et al., 2014), it becomes more difficult for the latter to compromise on audit quality, which guarantees audit quality. However, cancelling the DADRS foregoes the positive spillover effect from HK auditors and audit quality is likely to be impaired.

Previous literature has only explained this potential positive spillover effect. It has not yet been measured, and thus, it remains unclear whether and to what extent its existence and loss have affected audit quality. Our research aims to fill this gap. In particular, we measure the positive spillover effect from HK auditors. When a sampled AH firm keeps the DADRS, it is calculated as the negative value of the absolute difference between the H-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals (audited by the HK auditor) and the A-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals (audited by the MC auditor).

Using a sample of 263 AH firm-year observations from 2010 to 2015, we find that AH firms keeping the DADRS have higher audit quality when they are subject to a stronger positive spillover effect from HK auditors, suggesting that the existence of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors is beneficial to the audit quality of AH firms. Furthermore, we find that after AH firms cancel the DADRS, there is a positive association between the loss of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors and the decrease in audit quality, suggesting that this loss is primarily responsible for the decline in audit quality of AH firms cancelling the DADRS. We also find that our results are unlikely to be attributable to major confounding factors in the cross-listing setting comprising AH firms, such as (i) the convergence of the CAS with the IFRS and (ii) the concern of engaged auditors (in the DADRS) regarding their shared reputational risk when they belong to the same brand. Moreover, our results are not seriously affected by self-selection bias, and changing the audit-quality proxy does not alter our inferences.

Our study contributes to the literature in the following ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that constructs a measure to empirically represent the positive spillover effect from a high-quality auditor (i.e., HK auditor) to a low-quality auditor (i.e., MC auditor) using the institutional setting of the DADRS. Although previous literature elaborates on this effect, there is no valid measurement or examination of it. To fill this gap, we follow regulatory rules and Ke et al.’s (2015) argument to derive a measure based on the calculation of the distance between the H-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals and the A-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals of an AH firm; we consider that this measure properly captures the indirect positive spillover effect from HK auditors.

Second, the findings highlight the indispensable role of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors in the dual audit regime. Specifically, we provide initial direct evidence that a positive spillover effect from HK auditors helps ensure the higher audit quality of AH firms using the DADRS. Moreover, the cancellation of the DADRS leads to a decline in audit quality, mainly driven by the loss of this positive spillover. Our analyses have at least three advantages over those of previous studies. First, we incorporate analyses of changes into the empirical process and limit our sample to AH firms. This enables us to overcome omitted variable problems and rules out the impact of systematic differences between cross-listings and non-cross-listings. Second, we address the impact of reporting standards when strengthening our main results. This accounting-related factor is very likely to drive the results under the AH cross-listing background; however, it has been largely overlooked by previous research on the role of audits. Third, we focus on A-share audits conducted by both the Big 4 member firms in mainland China and the MC non-Big 4 auditors, rather than exclusively focusing on the former. We also control for an indicator of the cases in which the two engaged auditors in the DADRS are member firms belonging to the same cross-border brand; alternatively, we re-run the baseline models after removing these cases. These strategies contribute towards substantially addressing the engaged auditors’ concern regarding shared reputational risk, which prior studies have not emphasised.

Third, our study adds to the growing trend of research based on emerging markets, specifically, the Chinese audit market. The increasing importance of China in the Asia-Pacific economy and its unique institutional characteristics have raised the interest of researchers from the Asia-Pacific region on auditing issues in China. To the extent that regulation affects audit quality (Knechel, 2016; De Villiers and Hsiao, 2018), one topic at issue is the influence of China’s ongoing regulatory changes and institutional uniqueness with regard to audit quality. Our research reveals an important determinant of audit quality in the Chinese market, namely, the positive spillover effect from HK auditors to MC auditors. This determinant reflects not only the weaker institutional environment of China compared to developed markets, but also the adverse impact of a regulatory change, namely, the abolition of the mandatory DADRS.

Finally, our study has profound policy implications. We directly test the impact of DADRS cancellation on the audit quality of its target: AH firms. We find a significant decline in audit quality for AH firms that opt out of this regime, largely driven by the loss of a positive spillover effect from HK auditors. Our findings confirm practitioners’ concern about likely damage to AH firms’ audit quality when audits are performed solely by MC auditors (Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEx), 2010; Yiu, 2010; Lee, 2011). From this perspective, it might not be wise for an AH firm to cancel the DADRS in order to save costs. As shown in Section 2 and Table 3, while the proportion of AH firms cancelling the DADRS has grown since 2010, they comprise only a small part of the total AH sample at the end of our sample period (i.e., 2015). This phenomenon reflects AH firms’ doubt about whether the economic benefits from the cancellation of the DADRS can exceed its quality-related costs. Accordingly, the implementation of this policy change has not been as effective as regulators originally expected, and opting out of the DADRS is still far from becoming a common trend among AH firms. Our study reinforces the benefits of the dual audit system for audit quality. Policymakers and regulators should cautiously reassess the appropriateness of the abolition of the mandatory DADRS. The implication for other emerging markets with audit rules and regulations that have not yet been well developed is that auditing systems adapted to national conditions may be uneconomical, but not to the extent that they erode the benefits of developing a high-quality financial reporting environment.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides the institutional background, followed by a literature review in Section 3. Section 4 develops the research hypotheses. Section 5 presents the research design. After a discussion of the empirical results in Section 6, Section 7 concludes.

2 Institutional background

China’s A-share stock market was established in the early 1990s. The first AH firm, mainland Chinese company Tsingtao Brewery, was cross-listed in 1993. At that time, substantial differences existed between the CAS and the IFRS (or HKFRS). Moreover, MC audit firms were considered to have relatively low audit quality. Therefore, the listing rules and regulations in mainland China and Hong Kong required an AH firm to prepare two sets of annual financial statements; it was also compulsory for these financial statements to be audited by two separate audit firms. This dual audit requirement is known as the mandatory DADRS. Specifically, the mandatory DADRS required an AH firm to prepare its A-share financial statements in accordance with the CAS and to hire an MC audit firm to perform the audits as per the mainland auditing standards. The regulation also required the firm to prepare its H-share financial statements according to the IFRS (or HKFRS) and to engage a HK audit firm to perform the audits using the international (or Hong Kong) auditing standards. Each of the two audit firms was required to release a separate annual audit report for the same AH firm. While this mandatory system increased the listing costs of AH firms, it was aimed at meeting the different information demands of Chinese and international investors.

The CAS were updated in 2006 by China’s MOF. The new CAS, which took effect on 2007, reflect substantial convergence (equivalence) of the CAS with the IFRS (HKFRS; Kuan and Noronha, 2007). However, the convergence of the financial reporting standards between mainland China and Hong Kong compelled regulators to consider the futility of the existence of the mandatory DADRS. Accordingly, the regulators took several steps to abolish the requirement and to encourage qualified MC audit firms to perform sole audits on AH firms.

In 2007, the China Accounting Standards Committee (CASC) and the Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants (HKICPA) signed a joint declaration on the Converged CAS and HKFRS (China Accounting Standards Committee (CASC) and Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants (HKICPA), 2007), explicitly expressing the intention to abolish the mandatory DADRS in the near future. Subsequently, in August 2009, a Consultation Paper on Acceptance of Mainland Accounting and Auditing Standards and Mainland Audit Firms for Mainland Incorporated Companies Listed in Hong Kong was published by the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEx) (2009). This document proposed that the Hong Kong market accept mainland China’s accounting and auditing standards for AH firms. It also suggested allowing MC audit firms to audit AH firms independently.

Finally, on 10 December 2010, the HKEx reached an agreement with the CSRC agreeing to accept mainland accounting and auditing standards and MC audit firms for AH firms. Specifically, an AH firm would be allowed to prepare one set of financial statements under the CAS, and correspondingly hire an MC audit firm to perform the audits based on the mainland auditing standards. Meanwhile, the regulators approved 12 large MC audit firms to audit AH firms independently for fiscal years ending on December 15, 2010 at the earliest (Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEx), 2010). Since then, the DADRS has become voluntary for AH firms.

3 Literature review

Some prior studies on the DADRS compare audit quality across different groups in the period when the mandatory DADRS was still in place. For example, Lin et al.(2014) find that China’s A-share listed companies that are required to adopt DADRS have greater auditor conservatism than those that are not bound by this requirement. In addition, auditor conservatism is highest when the engaged MC and HK audit firms belong to different brands. Wang and Xin (2011) compare Big 4 and non-Big 4 auditors under the DADRS. They find that, in most cases, when an AH firm hires an MC member firm belonging to a Big 4 brand for its A-share audits, it also hires a HK member firm from the same brand for its H-share audits. Thus, any misconduct by one of the audit firms would impair the Big 4’s international reputation and the other auditor would also be adversely affected. Non-Big 4 auditors, however, have no such concerns. Wang and Xin’s (2011) empirical results show that such a difference in motivation increases the audit quality of AH firms audited by Big 4 auditors compared to that of non-Big 4 auditors’ AH clients.

Other studies also involve observations in the period after the abolition of the mandatory DADRS. Wang (2014) studies the effect of the DADRS on audit quality among non-Big 4’s clients using data in 2001–2012. She finds that the audit quality of AH clients is higher than that of clients listed only on the A-share market, suggesting that the DADRS contributes to improving audit quality. Focusing on A-share audits conducted by Big 4 auditors in 1995–2012, Ke et al.(2015) find that Big 4 firms assign more-experienced partners and guarantee higher audit quality for their AH-share clients using the DADRS than for other A-share clients. Ke et al.(2015) attribute their findings to a positive spillover effect from HK auditors through the DADRS. Using data on A-share firms in 2007–2014, Tian et al.(2016) find that mainland auditors (including Big 4 and non-Big 4 auditors in mainland China) exert more audit effort and provide higher audit quality for AH firms using the DADRS than for other A-share firms. Sun (2013) focuses on changes in audit market structure and audit fees after the abolition of the mandatory DADRS. Using data on AH firms in 2006–2011, she finds that Big 4 auditors still occupy a large market share in the mainland audit market; after the policy change, audit fees even increase in some firms.

At least two points can be drawn from the existing research. First, previous literature concurs that the audit quality of A-share listed companies not using the DADRS (including firms listed only in mainland China and some AH firms) is lower than that of AH firms using the DADRS. It can be inferred from this general finding that the audit quality of AH firms possibly decreases following the DADRS cancellation. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the general finding of these studies is driven by systematic differences between cross-listings and non-cross-listings rather than by variation in audit systems. Second, Ke et al.(2015) provide a noteworthy and detailed explanation of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors for the first time in the literature. This aids understanding of the mechanism by which the DADRS ensures high audit quality from the perspective of the institutional environment faced by the engaged auditors. Nevertheless, the positive spillover effect proposed by Ke et al.(2015) is limited to a description. The effect has not yet been measured directly, and it is still unclear whether and to what extent its existence and loss affect audit quality. These issues are addressed in this study.

4 Hypothesis development

H1: An AH firm exposed to a stronger positive spillover effect from a HK auditor has higher audit quality.

H2: The loss of a positive spillover effect due to the cancellation of the DADRS by an AH firm leads to a decline in its audit quality.

5 Research design

5.1 Sample and data collection

For our sample, we obtain all AH firm-year observations between 2010 and 2015 from the China Securities Markets & Accounting Research database and the WIND database. This yields an initial sample of 475 firm-year observations. For the estimation of the audit quality change models (i.e., Eqns (3) and (5)), we need data from the preceding year, and thus, the data collection for these observations starts from 2009. Next, we drop 24 observations for firms that were delisted or terminated, or had special treatment labels, given their substantial differences in firm characteristics from other listed firms. Subsequently, we exclude 85 observations in the financial industry because of their different reporting standards. We also delete 79 observations of AH firms listed on the A-share market or the H-share market after 2010. Finally, after removing 24 observations with missing data, 263 AH-share firm-year observations (i.e., 47 firms) are left for the main tests. Out of the 263 observations, 192 retained the DADRS. We use the subsample of 192 observations to examine H1, and the full sample of 263 observations to examine H2. Table 1 shows the sample selection process.

| Description | No. of observations |

|---|---|

| AH firm-year observations during 2010–2015 | 475 |

| Less: observations delisted, terminated, or under special treatment | (24) |

| Less: observations in financial industry | (85) |

| Less: observations of AH firms listed on the A-share market or the H-share market after 2010 | (79) |

| Less: observations with missing data | (24) |

| Final sample (47 firms) | 263 |

All variables in Equations (2)–(5) are derived from the A-share financial and audit data of the sample firms, except for that measuring the positive spillover effect from HK auditors (i.e., Spillover), which is calculated using both A-share and H-share financial data. We winsorise all continuous variables at 1 and 99 percent to mitigate the influence of outliers.

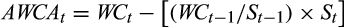

5.2 Measurement of audit quality

()

()5.3 Measurement of positive spillover effect from Hong Kong-based auditors

For the same business transaction, an AH firm is not allowed to use different accounting estimates in its A-share and H-share financial statements (China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), 2001). Therefore, an AH firm’s A-share financial statements are supported by accounting assumptions that are inseparably connected with the assumptions underpinning its H-share financial statements (Ke et al., 2015). Meanwhile, given that the A-share and H-share financial statements are compiled based on different accounting standards (i.e., the CAS and IFRS), there is some flexibility for an AH firm to choose different accounting policies for different sets of financial statements. However, even if an AH firm has this freedom of choice, it is compulsory for the firm to reconcile its A-share and H-share financial statements and to elaborate in its annual reports about the differences in accounting policy. The engaged auditors are required to keep a close eye on whether the reconciliation is authentic and complete. With these constraints, the stricter H-share audits of an AH firm can help prevent earnings management in the firm’s A-share financial statements, and thereby have a positive spillover effect on its A-share audits (Ke et al., 2015). Accordingly, we expect that a closer gap between an AH firm’s H-share’s absolute abnormal accruals and its A-share’s absolute abnormal accruals in the dual audit process represents a larger constraint effect of the H-share audits on the A-share audits. In other words, for an AH firm keeping the DADRS, a shorter distance between the H-share’s absolute abnormal accruals audited by the HK auditor and the A-share’s absolute abnormal accruals audited by the MC auditor reflects a stronger positive spillover effect from the HK auditor. Subsequently, based on this rationale, we calculate the distance (i.e., absolute value of the difference) between the H-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals audited by the HK auditor and the A-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals audited by the MC auditor (i.e., ||AWCA|H-share − |AWCA|A-share|) for an AH firm keeping the DADRS. As it is more intuitive to assume a stronger positive spillover effect when the value of the relevant variable is larger, we flip the sign of ||AWCA|H-share − |AWCA|A-share| when constructing the variable. Specifically, we define a variable Spillover to equal − ||AWCA|H-share − |AWCA|A-share| when an AH firm keeps the dual audit; otherwise, Spillover equals 0 after an AH firm dismisses the HK auditor (i.e., cancels the DADRS). By definition, for an AH firm keeping the DADRS, a larger value of Spillover (i.e., shorter distance between |AWCA|H-share and |AWCA|A-share) implies a stronger positive spillover effect from the HK auditor.

Since the construction of both |AWCA|A-share and Spillover includes the A-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals, some may argue that these two variables actually measure the same object, and thereby are necessarily related to each other. We check the correlation between |AWCA|A-share and Spillover and the correlation between their change forms (i.e., difference in values of the two variables between the current and previous years: Δ|AWCA|A-share and ΔSpillover). The untabulated results show that while |AWCA|A-share (Δ|AWCA|A-share) is significantly and negatively correlated with Spillover (ΔSpillover), the correlation coefficient between |AWCA|A-share (Δ|AWCA|A-share) and Spillover (ΔSpillover) is only −0.279 (−0.177). This implies that |AWCA|A-share (Δ|AWCA|A-share) and Spillover (ΔSpillover) separately capture variations in different underlying constructs; it remains unclear whether Spillover (ΔSpillover) has a significant impact on |AWCA|A-share (Δ|AWCA|A-share) after controlling for other factors in the models in the following subsection.

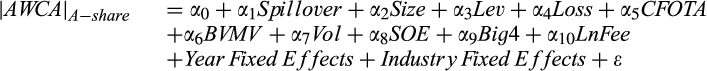

5.4 Regression models

5.4.1 Models for tests of H1

()

()Following Ke et al.(2015), we control for several firm-level characteristics, particularly, company size (Size), leverage (Lev), profitability (Loss), operating cash flow (CFOTA), book-to-market ratio (BVMV), volatility (Vol), and state-ownership (SOE). We also control for auditor type (Big4; Reichelt and Wang, 2010). In addition, audit fee (LnFee) is included to control for the confounding effects of fee decrease due to the DADRS cancellation. See Table 2 for the variable definitions. Finally, we include year fixed effects and industry fixed effects in the model.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Baseline models | |

| |AWCA|A-share | The absolute value of abnormal working capital accruals in the A-share financial statements, estimated from Equation (1) |

| Cancel | 1 after the firm cancels the DADRS, and 0 otherwise |

| Spillover | The negative value of the absolute difference between |AWCA|H-share and |AWCA|A-share before the firm cancels the DADRS, and 0 after the firm cancels the DADRS. |AWCA|H-share is the absolute value of abnormal working capital accruals in the H-share financial statements (estimated from Eqn (1)) before the firm cancels the DADRS, and 0 after the firm cancels the DADRS |

| Size | Natural log of total assets |

| Lev | Total liabilities divided by total assets |

| Loss | 1 if the firm reports a loss during the year, and 0 otherwise |

| CFOTA | Operating cash flow divided by lagged total assets |

| BVMV | Book value of equity divided by market value of equity |

| Vol | Standard deviation of residuals from the market model |

| SOE | 1 if the firm is ultimately controlled by the government, and 0 otherwise |

| Big4 | 1 if the firm engages a Big 4 auditor, and 0 otherwise |

| LnFee | Natural log of audit fees |

| Additional tests | |

| Con | The index of convergence of reporting standards, derived from Equation (A1) |

| Rep | 1 if the firm engages an MC auditor and a HK auditor from the same brand, and 0 otherwise |

| |DACC|A-share | The absolute value of performance-adjusted discretionary accruals in the A-share financial statements (Kothari et al., 2005) |

| Spillover2 | The negative value of the absolute difference between |DACC|H-share and |DACC|A-share before the firm cancels the DADRS, and 0 after the firm cancels the DADRS. |DACC|H-share is the absolute value of performance-adjusted discretionary accruals in the H-share financial statements before the firm cancels the DADRS, and 0 after the firm cancels the DADRS |

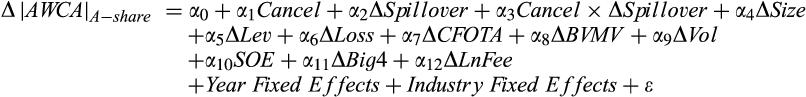

()

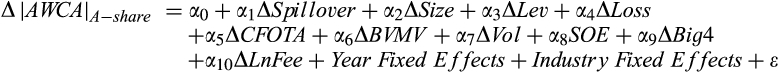

()5.4.2 Models for tests of H2

()

()Notably, introducing the interaction term of Cancel and Spillover in Equation (4) cannot test the impact of the loss of the positive spillover effect on the audit quality decline following AH firms’ cancellation of the DADRS stated by H2, because the variable Spillover captures only the positive spillover effect from HK auditors before the cancellation of the DADRS but becomes 0 for firms after the cancellation. Given this definition, interacting Cancel with Spillover is not meaningful, and a level version of the audit quality model cannot capture the loss of the positive spillover effect. By comparison, it is more appropriate to emphasise changes in positive spillover effect and audit quality in the analysis of H2.

()

()6 Empirical results

6.1 Sample distribution

Table 3 reports the sample distribution. Panel A shows a description of distribution by year. Column (1) shows that the annual distribution of the AH-firm sample rises from 2010 to 2013 and remains steady afterwards. Column (2) (column (3)) indicates that the number (percentage) of AH firms abolishing the DADRS grew after 2010, especially from 2010 to 2012 by an average of six firms (over 13 percent) per year. At the end of the sample period, 36.17 percent of the sampled AH firms cancelled the DADRS, whereas 63.83 percent of them retained it. Overall, these statistics suggest a variation among AH firms in terms of cancelling the DADRS; the cancellation of this audit system has been put into practice in a staggered manner since the 2010 deregulation. Panel B shows that the samples are distributed across six different industries. Manufacturing industry has the largest number of observations (110) and makes up 41.83 percent of the total observations, followed by transport, storage, and post industry (62 observations, 23.57 percent) and mining industry (48 observations, 18.25 percent).

| Panel A: Sample distribution by year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| No. of total samples | No. of samples cancelling the DADRS | % of total samples | No. of samples keeping the DADRS | % of total samples | |

| 2010 | 38 | 1 | 2.63 | 37 | 97.37 |

| 2011 | 40 | 9 | 22.50 | 31 | 77.50 |

| 2012 | 44 | 13 | 29.55 | 31 | 70.45 |

| 2013 | 47 | 15 | 31.91 | 32 | 68.09 |

| 2014 | 47 | 16 | 34.04 | 31 | 65.96 |

| 2015 | 47 | 17 | 36.17 | 30 | 63.83 |

| Total | 263 | 71 | 27.00 | 192 | 73.00 |

| Panel B: Sample distribution by industry | ||

|---|---|---|

| Industry | No. of total samples | % of total samples |

| Construction | 15 | 5.70 |

| Electricity, heat, gas, and water production and supply | 22 | 8.37 |

| Manufacturing | 110 | 41.83 |

| Mining | 48 | 18.25 |

| Real Estate | 6 | 2.28 |

| Transport, Storage, and Post | 62 | 23.57 |

| Total | 263 | 100.00 |

6.2 Descriptive statistics

Panel A of Table 4 reports the descriptive statistics for the level forms of the main variables. The mean (median) value of |AWCA|A-share is 0.039 (0.024). The mean value of Cancel shows that 27 percent of the total sample comprises the observations cancelling the DADRS. The mean (median) value of Spillover is −0.016 (−0.04). In general, the descriptive statistics of the control variables are similar to those reported by previous studies involving examination of AH firms, such as Ke et al.(2015). The mean values of Lev, Loss and BVMV are 0.583, 0.091 and 0.751, respectively, suggesting that the sampled AH firms are generally moderately indebted, profitable and with good growth opportunities. Of the total sample, 96.2 percent comprises state-owned enterprises (SOE). As for audit firm characteristics, Big 4 auditors (Big4) provide audit service for 65 percent of the total sample; the mean (median) value of LnFee is 15.793 (15.857), which can be converted to average audit fees of approximately RMB 7.22 million (RMB 7.7 million).

| Panel A: Level forms of the main variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Full sample (N = 263) |

Cancel = 1 (N = 71) |

Cancel = 0 (N = 192) |

Test of differences | ||||

| Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | 25% | 75% | Mean | Mean | t-stat. | |

| |AWCA|A-share | 0.039 | 0.024 | 0.043 | 0.012 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.036 | 1.873* |

| Cancel | 0.270 | 0.000 | 0.445 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Spillover | −0.016 | −0.004 | 0.029 | −0.018 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.022 | 5.900*** |

| Size | 24.784 | 25.079 | 1.694 | 23.910 | 25.820 | 24.132 | 25.025 | −3.893*** |

| Lev | 0.583 | 0.598 | 0.182 | 0.452 | 0.730 | 0.595 | 0.578 | 0.660 |

| Loss | 0.091 | 0.000 | 0.289 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.085 | 0.094 | −0.230 |

| CFOTA | 0.071 | 0.073 | 0.068 | 0.024 | 0.122 | 0.059 | 0.075 | −1.748* |

| BVMV | 0.751 | 0.668 | 0.426 | 0.432 | 1.002 | 0.727 | 0.760 | −0.550 |

| Vol | 0.080 | 0.070 | 0.039 | 0.053 | 0.099 | 0.082 | 0.079 | 0.483 |

| SOE | 0.962 | 1.000 | 0.192 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.944 | 0.969 | −0.942 |

| Big4 | 0.650 | 1.000 | 0.478 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.521 | 0.698 | −2.695*** |

| LnFee | 15.793 | 15.857 | 1.095 | 14.914 | 16.490 | 15.200 | 16.012 | −5.650*** |

| Panel B: Change forms of the main variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Full sample (N = 263) |

Cancel = 1 (N = 71) |

Cancel = 0 (N = 192) |

Test of differences | ||||

| Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | 25% | 75% | Mean | Mean | t-stat. | |

| Δ|AWCA|A-share | −0.000 | −0.001 | 0.049 | −0.021 | 0.017 | 0.006 | −0.003 | 1.213 |

| ΔSpillover | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.032 | −0.005 | 0.007 | 0.007 | −0.000 | 1.638 |

| ΔSize | 0.099 | 0.084 | 0.135 | 0.019 | 0.148 | 0.100 | 0.099 | 0.057 |

| ΔLev | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.053 | −0.024 | 0.031 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.651 |

| ΔLoss | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.365 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.005 | −0.102 |

| ΔCFOTA | −0.005 | −0.002 | 0.061 | −0.038 | 0.028 | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.065 |

| ΔBVMV | 0.042 | 0.046 | 0.296 | −0.087 | 0.226 | −0.007 | 0.060 | −1.634 |

| ΔVol | 0.004 | −0.002 | 0.033 | −0.013 | 0.017 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 1.168 |

| ΔBig4 | −0.008 | 0.000 | 0.123 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.010 | 0.607 |

| ΔLnFee | −0.006 | 0.000 | 0.339 | −0.049 | 0.058 | −0.013 | −0.004 | −0.206 |

- ***, ** and * represent significance at the 0.01, 0.05 and 0.10 level, respectively, using two-tailed tests. Variable definitions and measurement are reported in Table 2.

Panel B of Table 4 reports the descriptive statistics for the change forms of the main variables. The mean (median) value of Δ|AWCA|A-share is −0.000 (−0.001), suggesting that the audit quality of the sampled AH firms is relatively stable across years. The mean (median) value of ΔSpillover is 0.002 (0.000). Firm size rises 0.099 units per year on average (ΔSize), while the annual increase in the book-to-market ratio averages about 4.2 percent (ΔBVMV). The mean/median values of all the other control variables do not exceed 0.01 units or fall below −0.01 units, implying that the sampled AH firms witness gradual changes in these aspects on an annual basis.

6.3 Univariate tests

Panel A of Table 4 compares the mean values of the level forms of the main variables between the observations cancelling the DADRS (i.e., Cancel = 1) and the observations keeping the DADRS (i.e., Cancel = 0), while Panel B of Table 4 compares the mean values of the change forms of the main variables between these two groups. In both panels, the last column reports the t-statistics in the mean difference test. The mean |AWCA|A-share of the observations cancelling the DADRS (0.047) is significantly higher than that of the observations keeping the DADRS (0.036). Furthermore, the mean Δ|AWCA|A-share of the observations cancelling (keeping) the DADRS is 0.006 (−0.003), which suggests that abolishing (keeping) the DADRS is associated with a decline (improvement) in audit quality manifested as an average increase (decrease) of 0.006 (0.003) units in the absolute abnormal working capital accruals per year. These preliminary results are consistent with prior evidence on the negative impact of cancelling the DADRS on the audit quality of AH firms. The mean Spillover is −0.022 for the observations keeping the DADRS, which indicates that the average distance between the H-share’s absolute abnormal accruals audited by HK auditors and the A-share’s absolute abnormal accruals audited by MC auditors is 0.022. The mean value of ΔSpillover for the observations cancelling the DADRS is 0.007, which is slightly higher than the mean ΔSpillover for those keeping the DADRS (−0.000). In addition, the observations cancelling the DADRS have smaller firm size (Size) and lower operating cash flow (CFOTA), are less likely to engage a Big 4 auditor (Big4), and pay lower audit fees (LnFee) than the observations keeping the DADRS.

6.4 Baseline regressions

6.4.1 Tests of H1

Columns (1) and (2) of Table 5 report the results for the regressions of the A-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals on the positive spillover effect from HK auditors within the sample of 192 observations keeping the DADRS (i.e., Eqns (2) and (3)). In the level regression in column (1), the coefficient on Spillover is significant and negative (coefficient = −0.481, t = −2.524), which is consistent with H1 and suggests that AH firms’ audit quality is higher when they are subject to a stronger positive spillover effect from HK auditors. The result is also economically significant (see Appendix I). In the change regression in column (2), the coefficient on ΔSpillover is significant and negative (coefficient = −0.378, t = −2.038), suggesting a positive impact of an increase in the positive spillover effect from HK auditors on an increase in AH firms’ audit quality. This result provides additional support for H1. It is also economically significant (see Appendix I).

| Variable | Dependent variable: |AWCA|A-share | Dependent variable: Δ|AWCA|A-share | Dependent variable: |AWCA|A-share | Dependent variable: Δ|AWCA|A-share | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Intercept | 0.091 | 0.021 | 0.112* | 0.148 | 0.002 |

| (1.481) | (1.567) | (1.968) | (0.340) | (0.186) | |

| Spillover | −0.481** | −0.466** | −0.397*** | ||

| (−2.524) | (−2.420) | (−3.697) | |||

| ΔSpillover | −0.378** | −0.416** | |||

| (−2.038) | (−2.226) | ||||

| Cancel | 0.016** | 0.037*** | 0.011** | ||

| (2.219) | (3.004) | (2.155) | |||

| Cancel × ΔSpillover | 0.825** | ||||

| (2.049) | |||||

| Size | −0.007* | −0.006** | −0.006 | ||

| (−1.941) | (−2.224) | (−0.368) | |||

| ΔSize | 0.044 | 0.056 | |||

| (1.088) | (1.674) | ||||

| Lev | −0.004 | 0.013 | 0.053 | ||

| (−0.211) | (0.783) | (1.077) | |||

| ΔLev | −0.081 | −0.065 | |||

| (−1.190) | (−0.640) | ||||

| Loss | −0.010 | −0.001 | 0.007 | ||

| (−0.833) | (−0.059) | (0.642) | |||

| ΔLoss | 0.004 | 0.011 | |||

| (0.518) | (1.070) | ||||

| CFOTA | 0.115* | 0.068 | 0.133** | ||

| (1.837) | (1.208) | (2.176) | |||

| ΔCFOTA | 0.102 | 0.080 | |||

| (1.405) | (0.933) | ||||

| BVMV | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.015 | ||

| (0.218) | (0.323) | (1.069) | |||

| ΔBVMV | 0.018 | 0.008 | |||

| (1.224) | (0.576) | ||||

| Vol | 0.094 | 0.113 | 0.107 | ||

| (0.727) | (0.897) | (1.018) | |||

| ΔVol | 0.034 | 0.097 | |||

| (0.269) | (0.666) | ||||

| SOE | −0.020* | −0.032** | 0.002 | −0.046 | −0.012 |

| (−1.969) | (−2.598) | (0.244) | (−1.230) | (−1.505) | |

| Big4 | −0.012* | −0.008 | −0.022 | ||

| (−1.941) | (−1.352) | (−0.740) | |||

| ΔBig4 | −0.094*** | −0.035 | |||

| (−2.928) | (−0.798) | ||||

| LnFee | 0.008* | 0.002 | 0.001 | ||

| (1.853) | (0.597) | (0.138) | |||

| ΔLnFee | 0.015 | 0.000 | |||

| (1.625) | (0.008) | ||||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm FE | Yes | ||||

| N | 192 | 192 | 263 | 263 | 263 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.246 | 0.149 | 0.176 | 0.239 | 0.068 |

- Column (1) shows the results of Equation (2). Column (2) shows the results of Equation (3). Column (3) shows the results of Equation (4). Column (4) shows the results of Equation (4) with firm fixed effects included. Column (5) shows the results of Equation (5). ***, ** and * represent significance at the 0.01, 0.05 and 0.10 level, respectively, using two-tailed tests. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering on each firm. t-statistics are shown in parentheses. Variable definitions and measurement are reported in Table 2.

6.4.2 Tests of H2

Columns (3) and (4) of Table 5 report the results for the regressions of the A-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals on AH firms’ cancellation of the DADRS (i.e., Eqn (4)). In column (3), the coefficient on Cancel is significant and positive (coefficient = 0.016, t = 2.219), suggesting that AH firms’ audit quality is lower after they cancel the DADRS. The result is also economically significant (see Appendix I). This result confirms that cancelling the DADRS causes AH firms’ audit quality to deteriorate. In column (4), we include firm fixed effects, instead of industry fixed effects, in Equation (4) to ensure that we compare over time an AH firm’s observations that keep the DADRS with its observations that cancel it. The coefficient on Cancel remains significant and positive.

Column (5) of Table 5 reports the results for the regression of the change in the A-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals on AH firms’ cancellation of the DADRS and the change in the positive spillover effect from HK auditors (i.e., Eqn (5)). The coefficient on Cancel × ΔSpillover is significant and positive (coefficient = 0.825, t = 2.049). This result indicates that after the cancellation of the DADRS, there is a positive association of a loss of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors with a decrease in audit quality. This finding is consistent with H2 and implies that the removal (by the cancellation of the DADRS) of the positive spillover of HK auditors drives the decline of AH firms’ audit quality. The result is also economically significant (see Appendix I). In addition, the coefficient on ΔSpillover (Cancel) is significant and negative (positive), which is qualitatively similar to the results in column (2) (column (3)) of Table 5.

To further rule out the possibility that the audit quality difference/change we find is due to auditor upgrade or downgrade (rather than the existence and loss of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors), we estimate the above-mentioned models by excluding the samples that switch from a non-Big 4 auditor to a Big 4 auditor (i.e., auditor upgrade) or vice versa (i.e., auditor downgrade). The untabulated results suggest that our conclusions still hold.

6.5 Additional analyses

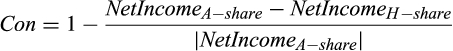

6.5.1 Convergence of reporting standards

As mentioned in Section 2, the abolition of the DADRS took place alongside convergence of the CAS with the IFRS. Hence, it may be argued that the variable we construct (i.e., Spillover) possibly captures the convergence of financial reporting standards between mainland China and Hong Kong rather than the auditing-related spillover effect. To address this concern, we compute the index of convergence of reporting standards (Con) following Haverty (2006) and Zhang (2014) (see Appendix II). We re-estimate Equation (2) with the inclusion of Con, and re-estimate Equations (3) and (5) with the inclusion of ΔCon. The results shown in Table 6 are qualitatively similar to our main results. Therefore, the convergence of financial reporting standards is unlikely to be an alternative explanation for our main findings.

| Variable | Dependent variable: |AWCA|A-share | Dependent variable: Δ|AWCA|A-share | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Intercept | 0.105 | 0.021 | 0.003 |

| (1.494) | (1.544) | (0.281) | |

| Spillover | −0.491** | ||

| (−2.579) | |||

| ΔSpillover | −0.377** | −0.418** | |

| (−2.031) | (−2.235) | ||

| Cancel | 0.012** | ||

| (2.305) | |||

| Cancel × ΔSpillover | 0.784* | ||

| (1.966) | |||

| Size | −0.008** | ||

| (−2.040) | |||

| ΔSize | 0.044 | 0.057* | |

| (1.063) | (1.685) | ||

| Lev | −0.004 | ||

| (−0.171) | |||

| ΔLev | −0.083 | −0.064 | |

| (−1.211) | (−0.631) | ||

| Loss | −0.008 | ||

| (−0.734) | |||

| ΔLoss | 0.003 | 0.012 | |

| (0.390) | (1.047) | ||

| CFOTA | 0.119* | ||

| (1.916) | |||

| ΔCFOTA | 0.101 | 0.080 | |

| (1.413) | (0.923) | ||

| BVMV | 0.001 | ||

| (0.135) | |||

| ΔBVMV | 0.018 | 0.009 | |

| (1.208) | (0.668) | ||

| Vol | 0.087 | ||

| (0.674) | |||

| ΔVol | 0.033 | 0.105 | |

| (0.257) | (0.747) | ||

| SOE | −0.020** | −0.032** | −0.013 |

| (−2.017) | (−2.579) | (−1.635) | |

| Big4 | −0.012* | ||

| (−1.902) | |||

| ΔBig4 | −0.094*** | −0.035 | |

| (−2.971) | (−0.788) | ||

| LnFee | 0.008* | ||

| (1.785) | |||

| ΔLnFee | 0.015 | −0.000 | |

| (1.644) | (−0.006) | ||

| Con | −0.005 | ||

| (−0.523) | |||

| ΔCon | 0.005 | −0.008 | |

| (0.432) | (−0.568) | ||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 192 | 192 | 263 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.243 | 0.145 | 0.066 |

- Column (1) shows the results of Equation (2) with Con included. Column (2) shows the results of Equation (3) with ΔCon included. Column (3) shows the results of Equation (5) with ΔCon included. ***, ** and * represent significance at the 0.01, 0.05 and 0.10 level, respectively, using two-tailed tests. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering on each firm. t-statistics are shown in parentheses. Variable definitions and measurement are reported in Table 2.

6.5.2 Auditors’ concern about shared reputation

It is a common practice that AH firms choose two audit firms from the same brand when performing the dual audit (see Appendix III). Therefore, the higher audit quality before the cancellation of the DADRS is likely to result from the two engaged auditors’ concern that their shared brand would lose reputation if either of the two audits were to fail rather than from the positive spillover effect from HK auditors. We define Rep to equal 1 when the MC auditor and the HK auditor hired by an AH firm are member firms sharing the same brand (including both the cases of the same Big 4 brand and those of the same non-Big 4 brand), and 0 otherwise. We re-estimate Equation (2) with the inclusion of Rep, and re-estimate Equations (3) and (5) with the inclusion of ΔRep. The results in Table 7 are consistent with the main results in Table 5, which implies that our main results are not driven by the engaged MC and HK auditors’ concern about potential damage to their shared reputation or by any change in this concern. Furthermore, we re-estimate Equation (5) by removing the cases in which shared reputational concern between the two engaged auditors may exist (i.e., drop observations for which Rep = 1). The inferences drawn from this reduced sample, as shown in column (4) of Table 7, remain unchanged.

| Variable | Dependent variable: |AWCA|A-share | Dependent variable: Δ|AWCA|A-share | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Intercept | 0.083 | 0.017 | 0.001 | −0.003 |

| (1.402) | (1.268) | (0.093) | (−0.097) | |

| Spillover | −0.490** | |||

| (−2.564) | ||||

| ΔSpillover | −0.397** | −0.420** | −0.570* | |

| (−2.127) | (−2.252) | (−2.042) | ||

| Cancel | 0.013** | 0.038* | ||

| (2.136) | (1.741) | |||

| Cancel × ΔSpillover | 0.950** | 1.006** | ||

| (2.075) | (2.175) | |||

| Size | −0.008* | |||

| (−1.828) | ||||

| ΔSize | 0.040 | 0.054 | 0.058* | |

| (1.050) | (1.669) | (1.728) | ||

| Lev | −0.006 | |||

| (−0.285) | ||||

| ΔLev | −0.095 | −0.064 | −0.118 | |

| (−1.190) | (−0.628) | (−0.563) | ||

| Loss | −0.009 | |||

| (−0.786) | ||||

| ΔLoss | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.015 | |

| (0.331) | (1.036) | (0.642) | ||

| CFOTA | 0.114* | |||

| (1.874) | ||||

| ΔCFOTA | 0.086 | 0.077 | 0.072 | |

| (1.140) | (0.902) | (0.634) | ||

| BVMV | 0.001 | |||

| (0.148) | ||||

| ΔBVMV | 0.016 | 0.007 | 0.004 | |

| (1.114) | (0.491) | (0.180) | ||

| Vol | 0.088 | |||

| (0.727) | ||||

| ΔVol | 0.021 | 0.091 | 0.325 | |

| (0.164) | (0.628) | (1.098) | ||

| SOE | −0.022* | −0.029** | −0.011 | −0.012 |

| (−1.924) | (−2.579) | (−1.216) | (−0.809) | |

| Big4 | −0.015 | |||

| (−1.427) | ||||

| ΔBig4 | −0.097** | −0.037 | −0.015 | |

| (−2.651) | (−0.859) | (−0.290) | ||

| LnFee | 0.009 | |||

| (1.545) | ||||

| ΔLnFee | 0.011 | −0.001 | −0.047 | |

| (1.238) | (−0.074) | (−1.041) | ||

| Rep | 0.006 | |||

| (0.349) | ||||

| ΔRep | 0.134*** | 0.018 | ||

| (7.066) | (0.933) | |||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 192 | 192 | 263 | 98 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.242 | 0.189 | 0.068 | 0.121 |

- Column (1) shows the results of Equation (2) with Rep included. Column (2) shows the results of Equation (3) with ΔRep included. Column (3) shows the results of Equation (5) with ΔRep included. Column (4) shows the results of Equation (5) after removing the observations for which Rep = 1. ***, ** and * represent significance at the 0.01, 0.05 and 0.10 level, respectively, using two-tailed tests. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering on each firm. t-statistics are shown in parentheses. Variable definitions and measurement are reported in Table 2.

6.5.3 Addressing the self-selection issue

An endogeneity problem can arise from AH firms having a voluntary choice to continue with or cancel the DADRS after 2010. Thus, the main findings could result from self-selection bias. We conduct analyses of changes in the main tests to eliminate bias induced by time-invariant factors. To further address the concern that unobservable time-varying factors drive the audit quality difference/change we find, we use the impact threshold of a confounding variable (ITCV) method, following Frank (2000) and Croci and Petmezas (2015). We calculate the ITCV for the variable Cancel. The threshold value for Cancel in the level model is 0.0808, implying that the significant result becomes an insignificant one once each of the partial correlations between |AWCA|A-share and the unobserved variable and between Cancel and the unobserved variable reaches 0.284

. The threshold value for Cancel in the change model is 0.0367, suggesting that the significant result becomes an insignificant one once each of the partial correlations between Δ|AWCA|A-share and the unobserved variable and between Cancel and the unobserved variable reaches 0.192

. The threshold value for Cancel in the change model is 0.0367, suggesting that the significant result becomes an insignificant one once each of the partial correlations between Δ|AWCA|A-share and the unobserved variable and between Cancel and the unobserved variable reaches 0.192

. The evidence shown in Appendix IV suggests that an unobserved confounding variable that can render the coefficients on Cancel statistically insignificant is unlikely to exist, given that we control for (i) a strong predictor of audit quality difference and change around the DADRS cancellation and (ii) a set of factors proven to have good explanatory power on variation in audit quality by the previous literature. We conclude that the stability of our results is not seriously affected by self-selection bias.

. The evidence shown in Appendix IV suggests that an unobserved confounding variable that can render the coefficients on Cancel statistically insignificant is unlikely to exist, given that we control for (i) a strong predictor of audit quality difference and change around the DADRS cancellation and (ii) a set of factors proven to have good explanatory power on variation in audit quality by the previous literature. We conclude that the stability of our results is not seriously affected by self-selection bias.

6.5.4 Alternative measurement of audit quality

We use the absolute value of discretionary accruals in the A-share financial statements (|DACC|A-share) as an alternative proxy for the audit quality of AH firms. This measure is calculated as the absolute value of residuals from the modified Jones model adjusted by controlling for operating performance (Kothari et al., 2005). Correspondingly, a variable, Spillover2, is constructed to measure the positive spillover effect from HK auditors. Spillover2 equals the negative value of the distance between the H-share’s absolute discretionary accruals and the A-share’s absolute discretionary accruals when an AH firm keeps the DADRS, and 0 after an AH firm cancels the DADRS. We re-estimate Equation (2) with |AWCA|A-share replaced by |DACC|A-share and Spillover replaced by Spillover2. We re-estimate Equations (3) and (5) with Δ|AWCA|A-share replaced by Δ|DACC|A-share and ΔSpillover replaced by ΔSpillover2. The results in Table 8 are similar to those reported in Table 5 and suggest that our inferences continue to hold for the alternative audit-quality measure.

| Variable | Dependent variable: |DACC|A-share | Dependent variable: Δ|DACC|A-share | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Intercept | −0.046 | 0.000 | −0.001 |

| (−1.063) | (0.033) | (−0.125) | |

| Spillover2 | −0.613*** | ||

| (−7.859) | |||

| ΔSpillover2 | −0.499*** | −0.443*** | |

| (−10.113) | (−7.856) | ||

| Cancel | 0.005* | ||

| (1.710) | |||

| Cancel × ΔSpillover2 | 0.270* | ||

| (1.927) | |||

| Size | 0.000 | ||

| (0.082) | |||

| ΔSize | −0.023 | 0.016 | |

| (−0.830) | (0.646) | ||

| Lev | −0.013 | ||

| (−0.903) | |||

| ΔLev | 0.021 | 0.016 | |

| (0.266) | (0.282) | ||

| Loss | 0.011 | ||

| (1.069) | |||

| ΔLoss | 0.019* | 0.017** | |

| (1.787) | (2.037) | ||

| CFOTA | 0.068 | ||

| (0.948) | |||

| ΔCFOTA | 0.139* | 0.139* | |

| (1.693) | (1.973) | ||

| BVMV | −0.012* | ||

| (−1.689) | |||

| ΔBVMV | 0.009 | −0.010 | |

| (0.705) | (−0.805) | ||

| Vol | 0.013 | ||

| (0.150) | |||

| ΔVol | 0.013 | −0.032 | |

| (0.122) | (−0.345) | ||

| SOE | 0.012* | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| (1.794) | (0.550) | (0.514) | |

| Big4 | 0.002 | ||

| (0.535) | |||

| ΔBig4 | −0.011 | −0.012** | |

| (−1.145) | (−2.297) | ||

| LnFee | 0.003 | ||

| (1.149) | |||

| ΔLnFee | −0.018* | −0.018 | |

| (−1.685) | (−1.586) | ||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 183 | 183 | 253 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.481 | 0.381 | 0.262 |

- Column (1) shows the results of Equation (2) with |AWCA|A-share replaced by |DACC|A-share and Spillover replaced by Spillover2. Column (2) shows the results of Equation (3) with Δ|AWCA|A-share replaced by Δ|DACC|A-share and ΔSpillover replaced by ΔSpillover2. Column (3) shows the results of Equation (5) with Δ|AWCA|A-share replaced by Δ|DACC|A-share and ΔSpillover replaced by ΔSpillover2. ***, ** and * represent significance at the 0.01, 0.05 and 0.10 level, respectively, using two-tailed tests. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering on each firm. t-statistics are shown in parentheses. Variable definitions and measurement are reported in Table 2.

7 Conclusions

In this study, we examine whether and to what extent a positive spillover effect from HK auditors to MC auditors in the DADRS affects the audit quality of AH firms. Our study is motivated by the growing importance of China as the biggest emerging economy in the Asia-Pacific region and the unique institutional features of the Chinese audit market. This includes low market concentration, high government interference, considerable regulatory changes, strong encouragement for the development of large mainland audit firms, and weak institutional environment. The positive spillover effect we focus on reflects not only the weaker institutional environment of the Chinese market compared to developed markets but also the influence of a regulatory change in China, namely, the abolition of the mandatory DADRS. We fill the gaps in previous literature by constructing a novel measure to represent the positive spillover effect from HK auditors. We provide evidence that this positive spillover effect, which exists in the DADRS, benefits the audit quality of AH firms, while the loss of this positive spillover drives audit quality to decline in AH firms cancelling the DADRS. Overall, our results suggest that the existence (loss) of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors positively (adversely) impacts AH firms’ audit quality after the retention (cancellation) of the DADRS.

Our study contributes to advancing understanding of the audit market in the largest emerging economy in the Asia-Pacific region. Our study extends the literature on the DADRS in China by taking an initial step towards empirical analysis to test the theoretical argument about (the loss of) an indirect positive spillover effect from HK auditors. Our study also extends the literature on audit quality by providing insights on an important determinant of audit quality in the Chinese market, namely, the positive spillover effect from a high-quality auditor (i.e., HK auditor) to a low-quality auditor (i.e., MC auditor). In addition, our study has significant policy implications for China. In line with practitioners’ concerns that AH firms’ audit quality would be impaired if they do not engage HK auditors, our findings demonstrate that the positive spillover effect from HK auditors helps to guarantee high-quality audits and foregoing this effect drives AH firms’ audit quality to decline. The findings suggest that it is unlikely that the decision to opt out of the DADRS can help an AH firm to achieve cost savings without sacrificing audit quality. Our study, to a certain degree, shows why few AH firms have responded to regulators’ call to cancel the DADRS, and hence, questions the value of this policy change.

The study has the following limitation. The sample size of AH firms that keep the DADRS in year t − 1 but cancel it in year t is very small, which restricts us to using average |AWCA|A-share over the years before and after the cancellation of the DADRS to test long-term audit quality deterioration after the cancellation. Nevertheless, as Cancel is assigned 1 for firm-year observations that not only cancel the DADRS in the current year but also all years afterwards, our empirical results still imply that audit quality deterioration persists years after the firms cancel the DADRS.

Appendix I: Economic significance of the main results

In the estimation of Equation (2), which is shown in column (1) of Table 5, the coefficient on Spillover is −0.481 (t = −2.524). With regard to economic significance, a 1 standard deviation increase in Spillover decreases |AWCA|A-share by 0.015, which translates into a 0.366 standard deviation decrease in |AWCA|A-share of the observations keeping the DADRS.

In the estimation of Equation (3), which is shown in column (2) of Table 5, the coefficient on ΔSpillover is −0.378 (t = −2.038). With regard to economic significance, a 1 standard deviation increase in the difference in values of Spillover between the current and previous years decreases the difference in values of |AWCA|A-share between the current and previous years by 0.013, which translates into a 0.283 standard deviation decrease in the difference in values of |AWCA|A-share between the current and previous years for the observations keeping the DADRS.

In the estimation of Equation (4), which is shown in column (3) of Table 5, the coefficient on Cancel is 0.016 (t = 2.219). With regard to economic significance, the coefficient of 0.016 translates into |AWCA|A-share being 0.372 standard deviation higher after AH firms’ cancellation of the DADRS.

In the estimation of Equation (5), which is shown in column (5) of Table 5, the coefficient on Cancel × ΔSpillover is 0.825 (t = 2.049). With regard to economic significance, for a 1 standard deviation increase in the difference in values of Spillover between the current and previous years, the change in the difference in values of |AWCA|A-share between the current and previous years is 0.539 standard deviation higher after the cancellation of the DADRS than before the cancellation. Notably, by definition, ΔSpillover has different interpretations for different situations. Before the cancellation of the DADRS, it means the change in the positive spillover effect from HK auditors, whereas after the cancellation, it means the loss of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors. Therefore, an increase in ΔSpillover means an increase in the change in the positive spillover effect for situations before the cancellation of the DADRS, while an increase in ΔSpillover means an increase in the loss of the positive spillover effect for situations after the cancellation of the DADRS.

Given the above-mentioned clear changes in the dependent variables driven by the changes in the independent variables of interest, our main results have both statistical and economic significance.

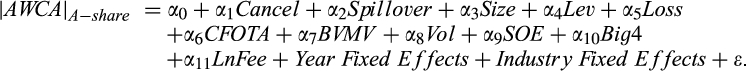

Appendix II: Calculation of the index of convergence of reporting standards

()

()Appendix III: Sample structure of observations keeping the DADRS

Statistically, around 85.9 percent of the sampled AH firm observations keeping the DADRS (165/192) engage an MC auditor and a HK auditor that are member audit firms sharing the same brand. This case represents 81.2 percent of firms (134/165) that engage auditors from the same Big 4 brand, and 18.8 percent of firms (31/165) that engage auditors from the same non-Big 4 brand. Firms that engage an MC non-Big 4 auditor and a HK Big 4 auditor account for 9.4 percent (18/192). The remaining 4.7 percent of firms (9/192) engage an MC non-Big 4 auditor and a HK non-Big 4 auditor from different brands.

Appendix IV: Impact threshold for a confounding variable analysis

The ITCV is the product of the following two partial correlations: between the dependent variable and the unobserved variable, and between the independent variable of interest and the unobserved variable. Its computation is based on the commonly known notion that the unobserved variable’s correlations with the dependent variable and the independent variable of interest jointly determine the bias introduced by this variable. The extent of the bias in the estimated coefficient on the independent variable of interest increases with the strength of these two correlations. Accordingly, the ITCV, which is regarded as the lowest correlation required to overturn a statistically significant result, can be a reflection of the extent of the bias. A larger ITCV value implies an ordinary least squares result that is more robust to unobservable factors (Fu et al., 2012).

We calculate the ITCV for the variable Cancel. In Panel A of Table A1, the threshold value for Cancel in the level model is 0.0808. This value implies that the significant result becomes an insignificant one once each of the partial correlations between |AWCA|A-share and the unobserved variable and between Cancel and the unobserved variable reaches 0.284

. Without comparative data, it is difficult to determine whether the ITCV is large enough to ensure the robustness of the result. We follow the previous literature and compute the impact of each control variable to benchmark the size of possible correlations involving the unobserved confounding variable. The impact of each control variable is defined as the product of the partial correlations between |AWCA|A-share and that control variable and between Cancel and that control variable. Column (2) of Panel A of Table A1 shows the potential impact of the inclusion of each control variable on the coefficient on Cancel. The ITCV (0.0808) is larger than the magnitude of impact scores of all control variables except Spillover (with an impact score of −0.0982), which means that we need an unobserved variable with a greater impact than Spillover to overturn the results. In Panel B of Table A1, the threshold value for Cancel in the change model is 0.0367, suggesting that the significant result becomes an insignificant one once each of the partial correlations between Δ|AWCA|A-share and the unobserved variable and between Cancel and the unobserved variable reaches 0.192

. Without comparative data, it is difficult to determine whether the ITCV is large enough to ensure the robustness of the result. We follow the previous literature and compute the impact of each control variable to benchmark the size of possible correlations involving the unobserved confounding variable. The impact of each control variable is defined as the product of the partial correlations between |AWCA|A-share and that control variable and between Cancel and that control variable. Column (2) of Panel A of Table A1 shows the potential impact of the inclusion of each control variable on the coefficient on Cancel. The ITCV (0.0808) is larger than the magnitude of impact scores of all control variables except Spillover (with an impact score of −0.0982), which means that we need an unobserved variable with a greater impact than Spillover to overturn the results. In Panel B of Table A1, the threshold value for Cancel in the change model is 0.0367, suggesting that the significant result becomes an insignificant one once each of the partial correlations between Δ|AWCA|A-share and the unobserved variable and between Cancel and the unobserved variable reaches 0.192

. Column (2) of Panel B of Table A1 shows that none of the control variables has an impact stronger than the ITCV (0.0367).

. Column (2) of Panel B of Table A1 shows that none of the control variables has an impact stronger than the ITCV (0.0367).

| Panel A: Results of the level model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Dependent variable: |AWCA|A-share | |

| ITCV | Impact | |

| (1) | (2) | |

| Cancel | 0.0808 | |

| Spillover | −0.0982 | |

| Size | −0.0044 | |

| Lev | 0.0155 | |

| Loss | 0.0004 | |

| CFOTA | −0.0003 | |

| BVMV | −0.0001 | |

| Vol | −0.0035 | |

| SOE | 0.0002 | |

| Big4 | 0.0002 | |

| LnFee | 0.0000 | |

| Panel B: Results of the change model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Dependent variable: Δ|AWCA|A-share | |

| ITCV | Impact | |

| (1) | (2) | |

| Cancel | 0.0367 | |

| ΔSpillover | −0.0156 | |

| ΔSize | 0.0014 | |

| ΔLev | −0.0022 | |

| ΔLoss | −0.0018 | |

| ΔCFOTA | −0.0023 | |

| ΔBVMV | −0.0051 | |

| ΔVol | 0.0038 | |

| SOE | 0.0027 | |

| ΔBig4 | −0.0033 | |

| ΔLnFee | 0.0000 | |

- Variable definitions and measurement are reported in Table 2.

References

- In December 2010, the following 12 firms were approved MC audit firms: BDO China Shu Lun Pan CPAs, Pan-China CPAs, Dahua CPAs, ShineWing CPAs, Ernst & Young Hua Ming CPAs, Crowe Horwath CPAs, Grant Thornton CPAs, PwC Zhong Tian CPAs, Deloitte & Touche Hua Yong CPAs, KPMG Hua Zhen CPAs, Ruihua CPAs, and Wuyige CPAs.

- We compare audit quality between HK auditors and MC auditors in the DADRS. For the group of 192 observations keeping the DADRS, the mean value of the H-share’s absolute abnormal accruals audited by HK auditors (|AWCA|H-share) is 0.035, which is slightly lower than the mean value of the A-share’s absolute abnormal accruals audited by MC auditors (|AWCA|A-share) (0.037). The difference between the mean values of |AWCA|H-share and |AWCA|A-share is −0.002, which is not significantly different from 0. This suggests that the practice of the DADRS follows the rule stipulated in the CSRC (2001) by ensuring that AH firms use accounting estimates with no essential distinctions in their A-share and H-share financial statements for the same accounting event. Meanwhile, given that lower absolute abnormal working capital accruals imply higher audit quality, the slightly smaller |AWCA|H-share (compared to |AWCA|A-share) indicates that HK auditors tend to have a positive spillover effect on MC auditors.

- In our sample, there is no case in which the difference between |AWCA|H-share and |AWCA|A-share of the same AH firm keeping the DADRS is exactly 0, while the value of Spillover is always 0 after an AH firm cancels the DADRS. Therefore, there is no overlap between the observations for which Spillover = –||AWCA|H-share – |AWCA|A-share| and those for which Spillover = 0.

- To further address any potential econometric problems from the construction by which the A-share’s absolute abnormal working capital accruals are included in both the dependent variables and the independent variables of interest in Equations (2)–(5), we use |AWCA|H-share to represent the positive spillover effect from HK auditors at a rougher level. We then rerun Equations (2)–(5) with Spillover (ΔSpillover) replaced by |AWCA|H-share (Δ|AWCA|H-share). The inferences drawn from these untabulated results are consistent with those from Table 5.

- We recognise that the loss of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors occurs only in the first year of an AH firm cancelling the DADRS. Thus, by making the variable Cancel equal 1 for all observations after an AH firm cancels the DADRS, we potentially understate the effect of the loss of this positive spillover when using the interaction term of Cancel and ∆Spillover to represent it.

- By definition, Cancel is assigned 1 for firm-year observations that not only cancel DADRS in the current year but also all years afterwards. Therefore, the observations cancelling the DADRS refer to situations after the cancellation of the DADRS.

- Doing so leaves only 27 observations for the estimation of Equations (2) and (3). This sample size is too small to meet the basic requirement of large sample statistical tests (i.e., at least 30 observations). Therefore, we do not re-estimate Equations (2) and (3) within this reduced sample.

- The common practice in audit research is to use proxies other than the accrual-related measures for robustness check. In our setting, however, the typical audit-quality proxies, like modified audit opinion and earnings restatement, are inapplicable owing to their lack of variation. Another classical measure, audit fees, is also unlikely to represent audit quality properly in our setting, as the original intention of regulators abolishing the mandatory DADRS is to reduce audit fees for AH firms, which implies that audit fees and audit quality are supposed to be considered separately. Furthermore, based on Ke et al.(2015) and the CSRC (2001), the most direct reflection of the positive spillover effect from HK auditors is a constraint on the A-share earnings management, which can be intuitively represented by the accrual-related measures. Thus, we use discretionary accruals to check robustness.