The angel investment decision: insights from Australian business angels

Abstract

While much has been written about the investment criteria of business angels, few studies explore why these particular criteria are important to them. The Australian context has a diverse range of actors along with complex jurisdictional arrangements, making for an interesting background for investigation of the angel finance phenomenon. We examine 12 business angels in the rapidly changing Australian context and use nine corroborating participants to validate responses and identify four key drivers – personal experience, trust, the need to contribute and realistic expectations – that influence business angels during the initial investment process.

1 Introduction

Tracey Beikoff was on the verge of closing her business; her invention, Rescue Swag, a first aid kit designed to be used as a sling, splint and immobilisation device, had sold only a couple of hundred units. She could not grow without more money, and she had exhausted her supply; she needed investment. Luckily, Tracey was able to connect with an angel investor who liked her product and saw that Tracey was keen to learn and try new things. Tracey got the capital and has sold nearly 100,000 rescue swags in just 2 years (Shark Tank, 2015).

Unfortunately, for thousands of other entrepreneurs, accessing capital is a significant problem. Getting seed funding, often from ‘triple F’ finances – founders, family and friends – is relatively straightforward. But like Tracey, many entrepreneurs struggle to get growth funding. And funding is just part of what new entrepreneurs need. They also need help finding new customers in order to grow and be successful (Gouveia, 2017). For this ‘smart’ finance, entrepreneurs turn to business angels, defined by Mason and Harrison (2008) as ‘a high net worth individual, acting alone or in a formal or informal syndicate, who invests his or her own money directly in an unquoted business in which there is no family connection and who, after making the investment, generally takes an active involve in the business’. This definition explains the what or who of a business angel, but not the why. What motivates business angels, like Tracey's, to invest in a business? What influences business angels in their decision making?

To address this question, we use a qualitative method to explore the decision-making process of angel investors. We conduct an abductive inquiry into the activities and behaviour of business angels, developing an understanding of the underlying drivers motivating angel financiers. To address the difficulty of finding business angels willing to be interviewed (Harrison and Mason, 1996; Vitale et al., 2006), we adopt the unique approach of interviewing active participants in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, providing corroborating evidence and developing insight into angel financing. This approach addresses concerns of a small population and provides a richer, more comprehensive understanding of the process, expanding the depth of the analysis (Morse et al., 2002). It is unique within the angel finance literature, representing a valuable technique for researchers.

There is substantial new research investigating business angels’ ‘investment criteria’ during the decision-making process (see, for example, Croce et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2016) adding to the established literature (Feeney et al., 1999; Mason and Stark, 2004). A key limitation of the extant literature is its failure to distinguish criteria used at the screening and detailed evaluation stages (Smith et al., 2010). We address this issue by breaking down investment criteria into discrete categories and linking them to the decision-making process, identifying primary influencing factors of business angels during the initial investment decision.

We identify and address three problems with the investment decision-making literature. First, exploration of the importance of post-investment involvement during the decision-making process is lacking. Post-investment involvement is a factor weighed by business angels prior to an investment being made and is considered as early as deal origination. Second, some models in the literature fail to adequately address the importance of the exit. We find that the exit is of particular importance to angels who consider it throughout the decision-making process even as early as deal origination. Third is the problem of application of investment criteria. While the literature assumes that criteria are linked to a screening/evaluation/due diligence stage, we find that they apply to each step of the decision-making process, suggesting that angel investment decisions are iterative and complex.

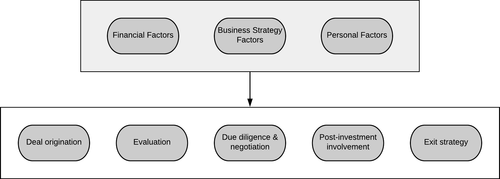

We make two contributions with our methodological approach. We develop an analytical framework addressing the challenges of the iterative nature of angel investments by integrating investment criteria with the decision-making process. These investment criteria, normally associated with an evaluation stage, are organised into three categories: financial factors, business strategy factors, and personal and relationship factors. In applying this framework, we contribute to the literature by using a unique approach of interviewing business angels along with other participants in the market in order to provide corroborating evidence.

We identify four themes driving the decision-making process of angel financiers in Australia: first, the role personal experience plays in the decision-making process, along with its influence on investment criteria; second, the importance of trust throughout the process; third, the emphasis placed by angels at the earliest stages of the decision-making process on their post-investment involvement; and finally, the importance of realistic expectations.

We begin this paper with a review of the literature, providing an overview of the Australian context and identifying gaps in the literature in relation to decision-making processes and angel investment criteria. We then outline our methodological approach, justifying a qualitative approach, identifying challenges and the ways we address these challenges. We offer an analytical framework from which we base the interviews. We then present the findings in the context of the four major themes identified during the analysis stage of the research. Finally, we offer some thoughts on the implications of these findings for future research.

2 Literature review

2.1 The Australian context

Despite a strong economy and a good supply of capital (Harrison, 2017), angel activity in Australia is relatively small scale. Estimates suggest that Australian angel investment per capita is less than $A15 compared with the US with $A103 per capita (Kinner, 2015). Despite this, the Australian business angel market is active and diverse, consisting of non-network affiliated angels, informal and formal angel networks, and angel groups/syndicates (Green, 2016). A peak body – the Australian Association of Angel Investors (AAAI) – aims to create resources to assist members in investment activities, although its level of activity is questionable. The contradiction between the level of angel finance provided compared to the activity within the market provides a context for asking what drives angel investors in Australia.

Research investigating the Australian angel finance market is limited. The first major study, by Hindle and Wenban (1999), provides a general profile of Australian business angels, and the second study, by Vitale et al. (2006), commissioned by the Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources (now the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science), provides a profile and an overview of the activities of Australian business angels. Beyond these studies, there are minor mentions of Australian business angels in industry research (see Cortez et al., 2007; AVCAL, 2013, Kinner, 2015) and a study on investment readiness (Douglas and Shepherd, 2002). In particular, there is little research into the investment criteria of Australian business angels, nor have the decision-making processes of Australian business angels been widely researched. This paper aims to fill this gap.

Australian governments are attempting to foster the entrepreneurial ecosystem1 through a range of policy programmes. While government policy cannot create an angel market (White and Dumay, 2017), well-designed policy can facilitate its development (OECD, 2011). Governments, universities, incubators and accelerators have highlighted a need to understand what drives business angels including, and beyond, investment criteria, in order to inform policy. While there is little information to claim that Australian business angels differ from business angels in other parts of the world, the context and environment in which they operate is experiencing a new and dramatic shift. This contextual change provides a backdrop to investigate the underlying drivers of the angel decision-making process.

2.2 Decision-making process of business angels

While business angels and institutional venture capital funds both aim to make a return, some investment criteria used by business angels differ from institutional funds (Harrison and Mason, 2000). Business angels seek to mitigate their risks through two methods: by investing in an industry or sector where they have experience (Wetzel, 1983) and by being actively involved in managing the firms in which they have invested (Mason and Harrison, 2000). Venture capitalists decide on whether to invest by looking at a proposed project, while business angels focus on the entrepreneur's ability to run the business (Aernoudt, 1999). Maxwell et al. (2011) add that business angels use shortcut decision-making heuristics. While formal investors tend to concentrate on risks linked to the product and the market, business angels focus on risks linked to the entrepreneur (Fiet, 1995; Aernoudt, 1999). Further, while analysis by formal investors is driven by financial factors, business angels are driven by the desire to guide and monitor a project (Aernoudt, 1999).

The findings of research into investment motivations of business angels are contradictory. For example, Hill and Power (2002) stress that, contrary to Aernoudt's (1999) findings, for some angels, cash is the primary (and only) motivation. Aernoudt's (1999) findings support early research recognising that non-financial rewards play an influential role in decision making (Wetzel, 1983) and have been identified as a main driver for angel investing (Tashiro, 1999). The importance of non-financial rewards is highlighted in the literature. For example, Stedler and Peters (2003) find that motivation for investing is a mix of financial and non-financial rewards, and that sharing professional experience and contributing to a successful start-up is considered particularly important.

The investment decision-making process of business angels has attracted considerable interest from scholars. White and Dumay (2017) note that research into angel decision making covers a broad range of topics, including readiness for funding (Brush et al., 2012), trust, agency issues and risk reduction (Lahti, 2011; Maxwell et al., 2011), and whether business angels place emphasis on the opportunity or the entrepreneur (Clark, 2008; Mitteness et al., 2012). Botelho (2017) discusses what business angels require in an investment proposal. The studies also enable incubators and governments to better understand what makes business angels different from other sources of capital, further highlighting the importance of business angels for the development of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Prevezer, 2001; Neck et al., 2004).

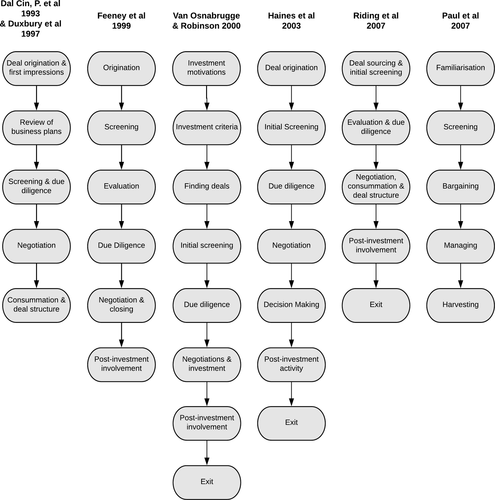

A number of researchers have examined the investment decision-making process, identifying different stages based on a ‘chronological’ or ‘linear’ approach (though some researchers highlight that, for business angels, the process is iterative, e.g. Paul et al., 2007; Haines et al., 2003). The multi-stage approach to the investment process provides a useful framework to develop an understanding of investment criteria and actions associated with each step (Botelho, 2017) and, ultimately, assists in identifying the underlying drivers influencing business angels during the initial investment process. Figure 1 summarises these different decision-making models.

Early research into the business angel investment decision process focused on formal venture capital decision making, with its five-stage model: deal origination, screening, evaluation, deal structuring and post-investment activities. The angel process is similar. Riding et al. (1993) and Duxbury et al. (1997) developed a five-stage model: deal origination and first impressions, review of business plan, screening and due diligence, negotiation and consummation. A limitation to this model is that it does not acknowledge angels’ post-investment involvement. Feeney et al. (1999) provides a literature synthesis documenting the linear progression of venture capital decision making, arguing that the decision-making process of business angels is similar to the process used by institutional investors. This model, shown in Figure 1, addresses the limitation of the Riding et al. model by including post-investment involvement. However, it lacks an exit stage.

Van Osnabrugge and Robinson (2000) present an eight-stage model they claim is applicable to both business angels and venture capitalists. Given the differences between these two types of investors, this claim is questionable (Mason and Stark, 2004), but the model makes a significant contribution by covering a greater range in the process (from pre-investment to exit) and by acknowledging the importance of factors considered prior to investment – motivations, criteria and the search for deals. Botelho (2017) suggests that these pre-investment criteria could be more efficiently placed in a single stage, deal origination, as in Haines et al.'s (2003) model; however, the iterative nature of angel investment decisions, particularly during familiarisation, screening and bargaining (Paul et al., 2007), suggests that criteria may be revisited during the different stages of the process.

The model proposed by Haines et al. expands Tyebjee and Bruno's (1984) five-stage model by introducing due diligence, negotiation and decision making as separate stages in place of evaluation and structuring. Haines et al. (2003), like Van Osnabrugge and Robinson (2000), includes an exit stage, emphasising ‘post-investment activity’. Van Osnabrugge and Robinson (2000) assert that this stage is a monitoring activity, whereas Haines et al. adopt a broader approach by including ‘value-added’ activities at this stage. A key strength of Haines et al.'s model is the clear separation of each stage across the entire investment process (Botelho, 2017), enabling more detail at each stage. These stages, however, are compressed by their later work (Riding et al., 2007), allowing for a simpler description of the process.

Paul et al. (2007) adopt a five-stage process noting that, while the angel investment process is generally sequential, it is not orderly and can be characterised as iterative. The first three stages of the research – familiarisation, screening and bargaining – represent an iterative assessment where the ability to validate both hard and soft data is crucial to progression to subsequent stages. These stages are further separated, with the familiarisation stage similar to deal origination with ‘meeting the entrepreneur’ added. The screening stage includes an initial and detailed screening where business angels use personal networks to assess the entrepreneur and, in addition to evaluating the business, determine what contribution they can make to the business beyond their financial investment. It is at this stage that a business angel decides to invest. Consequently, the amount of time spent on the proposal at this stage increases, with work on business plans a ‘back and forth’ process between angel and entrepreneur. The bargaining stage is the last of the ‘iterative’ stages proposed by Paul et al. (2007), corresponding to the ‘due diligence’ and negotiation stages presented in the preceding models.

The contribution of Paul et al. (2007) is significant as it highlights the iterative nature of angel investing. They argue that it is erroneous to suggest the process is straightforward and ‘neat’, but rather that it is an assessment that incorporates both market/business and personal factors (Paul et al., 2007). This is supported by Mason and Harrison (2003), who show that impression management abilities of entrepreneurs are critical when raising finance from external investors. Finally, Paul et al. (2007) highlight that business angels are more likely than venture capitalists to emphasise personal factors, a finding supported by a number of other studies (Mason and Stark, 2004; see Feeney et al., 1999).

2.3 Investment criteria

While research that provides entrepreneurs (Clark, 2008; Maxwell and Lévesque, 2010), policy makers (Freear et al., 1995) and prospective angels with a greater understanding of the factors that underpin and sustain the angel investment process (Paul et al., 2007) is useful, entrepreneurs benefit from further understanding the investment criteria of business angels. As noted in White and Dumay (2017), a number of studies investigate the investment acceptance (or desirability) and rejection (or shortcomings) criteria of business angels.

The criteria identified by the research can be categorised into three groups: financial factors, including valuation, capital requirements, forecasting, returns, etc.; business strategy factors, including market-based criteria, that is, level of competition, barriers to new entrants and product potential, etc.; and personal factors, such as entrepreneur experience and characteristics, as well as post-investment involvement considerations and exit preferences. Table 1 provides an overview of the investment criteria presented in the research, highlighting the key criteria used by business angels,2 presented as they appear in the respective research – acceptance or rejection criteria.

| Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|

| Authors | Acceptance/Desirability | Rejection/Shortcomings |

| Feeney et al. (1999) |

|

|

| Van Osnabrugge and Robinson (2000) |

|

|

| Mason and Stark (2004) |

|

|

| Sudek (2006) |

|

|

| Carpentier and Suret (2015) |

|

|

A review of the criteria provides three useful insights for structuring this work:

- The common factors related to the entrepreneur and their experience and personal characteristics, the angel's post-investment involvement and their ‘fit’ with the business, and financial considerations;

- The inconsistency of the exit as a criterion, with some questioning its importance at the early stage of the process (Botelho, 2017);

- The absence of deal origination as a consideration when assessing an opportunity.

Given Paul et al.'s (2007) finding that business angels examine proposals that do not meet their preference if referred to them by a trusted associate, it is reasonable to investigate the impact referral methods have, and the criteria related to referral methods and referees.

While some research argues that investment criteria apply only to the screening (evaluation) stage (an initial screening, followed by a more thorough evaluation; Mason and Rogers, 1997; Argerich, 2014), we argue that criteria, categorised as financial factors, business strategy factors and personal factors, apply to each stage of the decision-making process. The iterative nature of angel investment decisions supports this position. Reviewing the investment criteria literature, it is evident that different authors attribute investment criteria to different stages of the decision-making process. The stages of evaluation and due diligence and negotiation are self-evidently the central point for researchers to view investment criteria. However, at the deal origination stage investors consider the source of a deal as evidenced by Paul et al. (2007).

The literature states that business angels consider their contributions, beyond the financial, prior to investment (Van Osnabrugge and Robinson, 2000) – involvement being a motivation of business angels (Mason and Stark, 2004). While some research classifies ‘exit strategy’ as a criterion (Feeney et al., 1999; Sudek, 2006), the research consistently presents exit strategy as a stage in the decision-making process. Its inclusion in the research shows that it is considered as part of deal assessment, adding support to the argument that the investment criteria are applied throughout the decision-making process, rather than at a particular stage.

2.4 Summary and research question

Contemporary research has helped scholars to understand the decision-making process and angel investment criteria but further work is needed to unpack the complexity of angel investment decision making. This review calls attention to gaps in the research in relation to decision-making processes and investment criteria research and, particularly, the interaction of the two. Four key issues are identified in relation to the decision-making process:

- Lack of acknowledgement of post-investment involvement in some models;

- The exclusion of the exit stage in some models;

- Post-investment involvement seen as merely a monitoring activity rather than a value-added activity;

- The difficulty in addressing the iterative nature of the process using linear models.

Two main issues are identified in relation to the investment criteria research:

- The inconsistent use of the exit – a criterion for some, rather than a stage of the process where criteria are applied;

- The absence of deal origination and the application of criteria.

Separating the decision-making model from the criteria does not address the issues arising from this review. Decision-making research must address the fact that angels apply investment criteria at each stage of the process. By integrating the decision-making process models with the investment criteria, we address the research question: ‘what underlying drivers influence business angels during the investment decision-making process?’

3 Methodology

To answer the research question, it is necessary to develop a deeper understanding of the angel decision-making process. And to determine ‘what’ the ‘underlying drivers’ are, it is necessary to ask how and why. This approach is more explanatory and deals with operational links that need to be traced over time, rather than mere frequencies or incidence (Yin, 2014). We explore the perspectives of individual business angels, seeking to determine why decisions were taken and how they were implemented, and attempting to gain an insight into their experiences, thoughts and understanding of the investment process. To do this, the qualitative interview was chosen as the means of collecting data.

Interviews are useful when looking for detailed information about thoughts and behaviour, and provide a suitable platform for in-depth exploration of an issue (Boyce and Neale, 2006). Interviews allow the researcher to learn the perspectives of individuals and experiences, and are effective in discovering nuances (Jacob and Furgerson, 2012). Three broad categories of interview methods exist: structured, semi-structured and unstructured (Qu and Dumay, 2011). The structured interview approach views the interview as a tool producing objective data where interview bias is minimised (Rowley, 2012), but the minimisation of bias is at the expense of the ability to capture in-depth detail and the flexibility to change procedures and topics to adapt to the background of the interviewees (Doyle, 2004; Qu and Dumay, 2011). Given the interviewees for this study have different backgrounds and that we interviewed other players who can corroborate findings, the structured approach would yield little in the way of results.

The unstructured approach encourages respondents to ‘talk around’ a theme (Rowley, 2012), allowing the interviewer to adapt to what is being said (Bryman, 2001), but as it generates data that is difficult to compare and integrate (Rowley, 2012), it is not suitable for this study. We have chosen the semi-structured interview as the most suitable for this research as it allows interviewees to be pressed and prompted, ensuring that the question is answered sufficiently (Rowley, 2012), and to probe potentially interesting avenues of inquiry based on an understanding of the literature, the ecosystem and the interviewee. The benefit of this approach is a rich and varied body of data from which to draw results and conclusions.

We argue that the decision-making process and the investment criteria of angel investors cannot be satisfactorily addressed as separate components. Rather, these two research foci are interconnected subjects that should be treated as such in order to develop our understanding of angel investment decisions. We adopt an analytical framework (see Figure 2) that emphasises this interconnectedness. Further, the framework provides a basis from which to structure interviews and to present findings.

Table 2 provides a list of the participants, including 12 active business angels and one business angel network manager. Following these interviews, another eight participants were interviewed. These interviewees operated in related areas and included early stage venture capital limited partnerships, managers of incubators, and both federal and state government staff involved in the development or implementation of policy. Of these participants, two had past experience as angel investors. These interviews were conducted to gain further insight into points raised by the business angels, to provide corroboration and to add context to the research. In addition, we participated in less formal conversations with entrepreneurs, corporate venture capitalists (where the venture capital fund was financed by a non-financial institution) and other actors within the ecosystem. Where appropriate, the information garnered from these additional interviews and conversations has been included in the findings and discussions.

| Participant # | Gender | Description | Current or previous angel experience | Angel network |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | Angel investor | Yes | No |

| 2 | M | Angel investor | Yes | No |

| 3 | M | Angel investor and entrepreneur | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | M | Angel investor and entrepreneur | Yes | No |

| 5 | M | Angel investor and entrepreneur | Yes | No |

| 6 | M | Angel investor and entrepreneur | Yes | No |

| 7 | F | Angel investor and entrepreneur | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | M | Angel investor and entrepreneur | Yes | No |

| 9 | M | Angel investor and entrepreneur | Yes | No |

| 10 | M | Angel investor and investment banking (Capital raising) | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | M | Angel investor and private incubator | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | M | Angel investor, angel network board member and entrepreneur | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | F | Angel network manager | No | Yes |

| 14 | M | Corporate venture capitalist | No | No |

| 15 | F | ESVCLPa | No | No |

| 16 | M | Government – ESVCLP | Yes | No |

| 17 | M | Government – Program manager | No | No |

| 18 | M | Government – Program manager | No | No |

| 19 | M | Government – Program manager | No | No |

| 20 | F | Government – Program manager | No | No |

| 21 | M | Venture capitalist | Yes | No |

- a Early Stage Venture Capital Limited Partnerships are investment vehicles that provide tax exemptions for those investing in early and growth stage companies. They have a maximum fund size of $200 million (increased from $100 million in 2016).

We adopted a reflective pragmatist view (Alvesson, 2003) to interviewing, allowing for challenging of interpretations and the exploration of more than one set of meanings during and after the interviews, while balancing scepticism with a sense of direction. This process allows for a more sophisticated and nuanced understanding of the data collected and the contextual position of the participants. This approach also addresses the problem of participants not being ‘competent and moral truth tellers’ (Alvesson, 2003).

We adopt a localist approach to interviews, seeing the interview as an empirical setting that assists in interrogating complex social phenomena (Qu and Dumay, 2011) and as a social context rather than merely a tool for collecting data. This position emphasises that statements made must be viewed in their social context (Alvesson, 2003). Localist interview approaches allow for the study of facts without ignoring meaning and context. Localist interviewers are involved in the production of answers through interpersonal interaction (Qu and Dumay, 2011).

During interviews and conversations, we were frequently warned about the egos in the Australian angel market, giving rise to concern about the efficacy of some responses, that is, to be mindful of Alvesson's (2003) warning about interviewees as moral truth tellers. Responses are situated accounts to be understood in the social context of the interview. This, combined with the semi-structured approach, allows the researcher to probe further and challenge responses to elicit reflection and, in some cases, contradiction.

Interview protocols are best analysed via thematic strands extracted from the material through the researcher's interpretive and conceptual efforts (Crouch and McKenzie, 2016). Prior to each interview, we made notes on how we came into contact with the participant (snowball, personal approach, via personal networks) and any expectations we had about the interview. Following the interview, we made notes based on any thoughts about the benefits of the interview and about the participant and his or her manner.

The interviews were transcribed by a professional service and imported into NVivo,3 allowing for on-screen coding and real-time annotation. The software allows for an accurate and transparent analysis and a quick way of organising what was said, when and by whom, thus providing a good overview of the data (Welsh, 2002). Prior to reviewing the interviews, we created generic nodes based on the investment decision-making process outlined in the literature review. The handling of the data was an iterative process with coding followed by reflection, creation of annotations and more coding. This resulted in new nodes being generated during the interrogation of the data, which, along with the annotations to the coded text, formed the themes of the research. The coding model used was neither inductive nor deductive, but rather a mixture of the two (see Kelle, 1997), allowing for the development of clear themes articulated by the angel investors and corroborated by the other participants.

In terms of identifying participants, we found that the chosen definition of business angel was problematic if strictly applied. Hindle and Wenban (1999) use the criterion of net worth in their definition of Australian business angels, but the term ‘high net worth individual’ – a term used in wealth management to describe those people with investable assets >$US1 million (Baker, 2016) – was problematic. Many of the participants that identified as business angels are not classified as ‘high net worth individuals’ but do meet all the other criteria in the proposed definition. We did not restrict interviewees to only those classified as ‘high net worth’, as their history of direct investment of money and time and their identification with the term ‘angel investor’, qualified them for inclusion in this study.

Further, the phenomenon of ‘sweat equity’ – a party's work effort and time as opposed to financial equity – was problematic. Sweat equity investments are made with the expectation that a capital gain will be realised from the business at some point in the future. None of the participants could be defined as having sweat equity; however, some identified with the term in the context of previous experiences and many used the term in the context of a legitimate angel finance activity. Given the complexities of sweat equity – no financial transaction and no clear point where someone gains ownership of a firm – we do not consider sweat equity to be the same as angel financing and hence we have not included sweat equity investments in this research.

4 Findings and discussion

Using the framework outlined in Figure 2, we present the responses to our questions and identify four major themes evident in the findings. An interpretation and analysis of each participant, treated in isolation, only provides an understanding of that individual placed in his or her social context. At the same time, comparing individual responses provides a description of the interview and merely facilitates a list approach to what business angels want to see in an opportunity. While this is useful for entrepreneurs and business angels alike, this type of research already exists.

This research makes a novel contribution by examining the research questions: what underlying drivers influence business angels during the investment decision-making process? To answer the research question, it is necessary to draw on common threads identified across the range of participants. Corroborating interviews serve to validate these threads, which develop into significant themes (Yin, 2014). These themes exemplify the common social world occupied by the participants (Crouch and McKenzie, 2016). To identify these themes and address the research question, it is necessary to identify common discussion points raised by all participants (angels and corroborating participants).

We identify four themes influencing business angels through the entirety of the investment decision-making process, rather than at a single stage. These four themes are:

- The role of personal experience;

- The role of trust;

- The need to contribute; and

- Realistic expectations.

With these four categories cross-referenced to the decision-making process via the analytical framework, we address the research gap identified in the literature review and provide a contribution to the extant research. We address the problem of the iterative nature of the process by using an integrated approach in which we identify the importance of the deal origination as a stage subject to criteria, we integrate post-investment involvement throughout the decision-making process through ‘the need to contribute’, and we highlight the prominence of exit strategy as a further stage subject to criteria.

Table 3 presents a matrix summary of the findings. Each theme is cross-referenced to the major categories of the decision-making process (where evaluation, due diligence and post-investment involvement are subject to the criteria categories – financial, business strategy and personal and relationship factors). In organising the findings in this manner, we highlight that both deal origination and exit strategy are important and considered facets of angel investing. We also show that post-investment involvement is considered throughout the process via the ‘need to contribute’ theme. Of interest here is that ‘post-investment involvement’ does not relate to number of hours or the need to monitor, but rather the contribution investors can make to the business.

| Deal origination | Financial factors | Business strategy factors | Personal and relationship factors | Exit strategies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role of personal experiences |

15 |

9 |

17 |

13 |

15 |

| Role of trust |

21 |

15 |

16 |

15 |

13 |

| The need to contribute |

15 |

21 |

21 |

16 |

12 |

| Realistic expectations |

21 |

15 |

16 |

15 |

17 |

The matrix provides a unique way of categorising and presenting the data and addresses the problem of criteria being analysed in one stage of the decision-making process, while identifying the key drivers influencing business angels during their decision making. At the bottom of each cell are the number of respondents, providing triangulated evidence to support our findings. In the results, the cited interview transcript is an indicative example of the data.

4.1 Discussion of themes

4.1.1 Personal experience

Personal experience is a key driver in the investment process of business angels. The interviewed angels were adamant that their personal experience strongly guides them during both the decision-making process and post-investment involvement. Corroborating participants supported this finding, noting that an advantage that business angels bring is their knowledge and experience. Further, all participants acknowledged the importance of ‘smart money’, with angels saying they need to use their experiences to grow the business, and entrepreneurs saying that they do not want ‘only money’ (indeed, two entrepreneurs we spoke with stated that they turned down offers of capital because it did not add value to the business).

The theme of personal experience runs the entirety of the decision-making process. At deal origination, angels rely on personal experience with referees as a means of ‘vetting’ a deal. The interviewed angels noted that personal experience with the referee is important, with some angels going so far as to state that the quality of a proposal is related to the person referring it. When talking to participants who had referred deals, they noted that they would not pass on deals they believed were not sound. This highlights the importance that referees place on their reputation.

Personal experience can also be applied to the evaluation of an opportunity. Financial factors are largely born from personal experience and there was some inconsistency in the specific types of financial indicators used (for example, cash flows or profits). Given the broad cross section of participants, this is unsurprising – personal experience and past success strongly reinforce the strength of belief in a particular technique (highlighted with angels being adamant about their ‘best’ approach). Clearly, this presents difficulties for entrepreneurs seeking angel finance. However, a review of all responses identifies three factors for entrepreneurs to emphasise: cash flow, because businesses cannot grow without it; optimisation of the business model, that is, profit and cost; and, finally, harvesting the investment.

Business strategy factors are also driven by the experience of business angels, with some emphasising the importance of distribution channels, and others emphasising the need for customers (e.g. participant 10 said, ‘too few means you are at the mercy of someone else’). Knowledge and experience in a related industry is an important characteristic of angel investors, used to contribute to the business and, according to early research, to mitigate risk (Aram, 1989; Feeney et al., 1999). None of the participants discussed an angel's involvement in a business in the context of risk management. Instead, involvement was to add value to the business through his or her personal connections and experience in building a business. For example, one entrepreneur talked about an angel's ability to distribute products in international markets as a result of experience working in the US and China.

Personal experience impacts personal and relationship factors in a number of ways. First, angels noted the importance of founders retaining equity, often phrased as ‘skin in the game’. This was born from experience working with entrepreneurs who had little or no equity in a business and therefore had little reason to work hard – their livelihood no longer depended on how much effort they put into growing the business. Second, personal experience with the entrepreneur and with other investors is a positive for the angel investors. Finally, angels emphasised the importance of influencing company culture. This is based on previous experience and the understanding of the impact culture plays on a company's future success.

Personal experience also plays a role in the exit stage of the decision process. The participants stressed that angels consider likely exits before a deal is finalised. Prior experience underscores the issue of exit, with participants noting, not just that their experiences give them an understanding of the likely type of exit (trade sale), but also where those sales were likely to come from. When considering exit, angels used their personal experience to evaluate likely eventual buyers of the business. In other words, before a deal is made, angels scan the industry to identify what organisations may be interested in purchasing the business. This may be as simple as a larger organisation seeking to expand into a new market, or more complex as in a company whose underlying technology and systems may have different applications for larger companies. In any case, an angel's experience with identifying opportunities for harvesting is an important part of the decision-making process.

4.1.2 Trust

Trust as a determinant in angel investment decision making is well established (Harrison et al., 1997; Klabunde, 2015) and supported by both angel and corroborating participants in this research. Underscoring its importance is the fact that trust was consistently and repeatedly raised by participants, despite no direct questioning of the issue. Though participants expressed their thoughts on trust differently, there was generally agreement that trust (or trustworthiness) was made up of two components. First, trust in the entrepreneur's integrity, that is, their actions will be honest regardless of monitoring, and, second, trust in the entrepreneur's competence, that is, their ability to complete the relevant tasks. This is broadly in line with the trust research (see Gambetta, 1990; Sapienza and Zingales, 2012).

Two interesting points are identified in the context of trust and deal origination. First, angels will pass on deals to their colleagues if the business is outside their area of expertise. This highlights the complexities in the trust transaction and, more broadly, deal origination. Paul et al. (2007) states that business angels will review an opportunity outside of their expertise if it comes from a trusted source. However, in the case of the participants, they would not review a deal, but rather pass it to a colleague who has a better understanding of that particular type of business. This indicates that deal origination may be broken into a subset category model – those from angels and those from non-angels. While this separation may seem pedantic, it is clear that there are differences between the two and some contradiction between the literature and practice.

Second is the issue of angels operating within an angel network. Personal experience with the referee is important, with network angels offering a unique perspective on trust and referral. Angel network members, along with some corroborating participants, noted that they were part of the network, not because it was a source of deals, but because of the relationships with other network members. Adding to this is the complication of deals originating from the network itself, or from the relationships between angel network members. Despite formal networks organising formal pitch events, participants stated that network deals originated via personal networks of trusted referees, rather than through the network itself. A number of participants (participants 6, 9 and 12) added that formal ‘pitch nights’ were simply opportunities to network with others and the ‘pitches’ were ‘merely entertainment’. This shows that, in spite of formal organisations and events, angel finance is still best accessed via informal networks.

The finding that Australian business angel networks are more social and entertainment-oriented is particularly interesting. This finding suggests that business angel networks in Australia are of questionable value – contradicting some of the existing literature. Collewaert et al. (2010) find that angel networks operating in Flanders have had a positive impact on a number of measures. Likewise, Christensen (2011) identifies a range of direct and indirect benefits of angel networks, highlighting the success of the Welsh network Xeros (now part of the Development Bank of Wales). Finally, Bonini et al. (2018) find that angel network membership has a number of benefits for both angels and entrepreneurs in Italy. Clearly, there are benefits of a strong, well-developed angel network community.

We do not have a definitive answer to why angel networks in Australia operate more as hubs for entertainment and social activities with investment activities occurring more informally. We conjecture that the slow development of networks in Australia, along with the lack of coordinating organisation, has led to this problem. This conclusion has some support in the literature. For example, Christensen (2011) notes that markets that have a well-developed venture capital and equity culture are likely to have ‘organic’ (bottom-up) establishment of angel networks. However, these networks are hindered by a lack of coordinating organisation. We call for government intervention in this segment of the market to address this deficiency.

In relation to financial factors, a number of points are highlighted by the interviews. Trust in a particular analytical technique is evidently important; this is built on previous experience noted in the preceding section. A further point, absent from the literature, is the necessity of honest and upfront negotiations with the entrepreneur. Of interest is the term ‘skin in the game’, whereby participants insist that the entrepreneur must retain a reasonable level of ownership of the firm. This is articulated by participant 4, who stated ‘if they don't have much ownership, then they act like an employee rather than an owner’. This view, repeated and corroborated by other participants, may be an additional way in which angels deal with the agency problem and is worth further investigation.

Trust extended into the two other categories of criteria – business strategy factors and personal and relationship factors. First, angel investors needed to trust the management of the firm (in addition to and beyond the entrepreneur). Second, using contacts and personal experience to verify information given to angels by the entrepreneur. Angels seek corroborating evidence to make a determination on the veracity of information in a business plan because, first, angels are weighing up the trustworthiness of the entrepreneur, and second (and more importantly), third-party information was used to determine if the opportunity is likely to succeed. Trust enters here via the trust an angel places in those third-party mechanisms.

In relation to personal factors, participants stated that entrepreneurs must be trustworthy, regardless of any contracts that may be put in place. Founders must be willing to listen and to trust the advice of business angels. Other investors must also be trustworthy, with participants postulating that there needs to be a pre-existing relationship between the angel and other investors, rather than trust based on reputation and not experience. This highlights not just the importance of trust, but also its complexity.

Trust has a minimal role when determining exit strategies, although it is still present. It was most evident with angel financiers who invested in order to develop an income stream. In other words, these angels trusted that the business would be able to pay out a regular dividend. With a less developed link to trust is the trust in potential buyers of the business and the method by which it occurs.

4.1.3 The need to contribute

The need to contribute, to add value, is a key driver for business angels, articulated in the literature as ‘post-investment involvement’. Participants stated that the ability to contribute in a positive way is of the utmost importance: ‘the only contribution can't be money – you may as well be a passive investor investing in the share market’ (participant 4). Entrepreneurs agree that ‘smart money’ is more important than just financial capital because it opens up new opportunities and provides access to skills, knowledge or contacts that would otherwise be unavailable. All business angels wanted to add value; however, beyond financial rewards, investing provides the opportunity to do something they enjoy, providing them with, as participant 7 noted, ‘a sense of achievement and fulfilment.’

The knowledge and experience of business angels is an important characteristic of angel investing and, according to early research, a way of mitigating risk (Wetzel, 1983; Aram, 1989). Participants did not see involvement as a risk mitigation strategy (though participant 2 mentioned being ‘close to my money’). The interviews highlight a portfolio approach to angel investing. Approximately two-thirds of the interviewed angels discussed diversification as a way of managing risk. This was supported, with a number of corroborating participants noting that they knew of angels adopting a diversification strategy. This finding is particularly interesting as diversification was not the subject of any direction questions. However, it raises questions as to the ability of angels to effectively manage their time and contributions, both financially and otherwise. Participant 7 claimed to have 30 active investments, and another (participant 12) claimed 18. With so many investments, the amount of time and capital that can be committed to any one deal is severely limited. Given that entrepreneurs are seeking ‘smart money’ and angels claim to want to ‘add value’, the efficacy of a portfolio approach must be questioned.

At the deal origination stage, angels consider what they can bring to the business in addition to their financial contribution. This provides some evidence that post-investment involvement is a consideration at the very earliest stages of the deal. Angels, and some corroborating entrepreneurs, discussed this in terms of whether an angel can add value to the business through their personal connections and experience. A number of angels stated that they thought about what potential customers they could bring, or what areas of the business they could improve with their experience – for example, new distribution channels or more efficient software system.

The need to contribute runs through each of the three categories of criteria. Angels think about their contributions beyond financial, using their understanding of the market and industry to identify new opportunities. To paraphrase the angel participants, ‘I need to understand the competitive nature of the industry – who are the major players and competitors, who do I know that might be able to help, can I get the business face time with potentially new and large customers, what changes can I make to get things moving in the right direction’. Understanding the fundamentals of the business is seen as crucial as to whether or not angels can contribute something of value.

The need to contribute extends to the enjoyment of the work. Many of the participants spoke about the importance of having a good working relationship with the entrepreneur (or angel). Without a good relationship, the ability to add value to the business was hampered. As noted in the previous section on trust, the willingness of an entrepreneur to listen and take advice is crucial. Angels, and some corroborating participants, all noted that they were guided by a rule of not dealing with difficult people. If an entrepreneur is difficult ‘you just end up treading water – it's soul destroying’ (participant 2).

Finally, the issue of exit relates to the need to contribute through the experience and knowledge of the angel. As noted, at early stages of investment, business angels are thinking about the exit options available. The contribution here is the understanding of what types of entities might be potential buyers of the firm, for example, a direct trade sale so that a company can enter a new market or sell a new product or selling the intellectual property or the underlying systems. A business angel contributes understanding of saleable assets (tangible or intangible) to identify potential buyers.

4.1.4 Realistic expectations

The interviewed angels indicated that it is important to be honest, upfront and realistic with the entrepreneur: ‘you need to explain what they are up for when they are taking your money’ (participant 4). This is highlighted by comments from angels and government representatives, who talk about the lack of understanding of what an equity agreement means for the venture. It is important that the entrepreneur knows what is expected in return for the provision of capital. Adding to this, and as a signal, the business angels agreed that the entrepreneur must maintain an equity stake: ‘it makes it very hard to walk and is a good omen for investors’ (participant 9). Further, entrepreneurs that did not have equity were viewed with suspicion: ‘what makes them think my money is less valuable than theirs?’ (participant 6).

Realistic expectations play an important role in deal origination and exit. The participants thought of these aspects at the same time – in other words, exit strategies were considered at the deal origination stage, highlighting the non-linear characteristics of angel investment decision making. All angels, as well as government representatives, said a new firm needed to have a realistic chance of success, though what this meant was difficult for the participants to articulate.

While a realistic appraisal of the likely exit is important, the participants considered flexibility and the ability to take advantage of opportunities that can arise as equally important. Paul et al. (2007) state that business angels have no clear preference about how an exit will occur; however, the interviewed angels (corroborated by other participants) clearly indicate that, while a trade sale is not just the most likely way, it is also the preferred exit. In a sector that lacks an organised secondary market, an angel uses her/his experience to provide a realistic expectation of an exit and to direct the firm towards it. As participant 8 stated, ‘you need to start nibbling around the market of a large player, just enough to get noticed’.

In terms of criteria, realistic expectations are most applicable to financial factors; however, they have relevance to both business strategy and personal and relationship factors. From the perspective of financial factors, it is important that discussions with entrepreneurs are transparent (further highlighting the importance of trust) and that entrepreneurs are realistic about the value of the firm. A number of angels emphasised this by way of examples of entrepreneurs approaching them with an idea and wanting capital to finance their venture. In such cases, the angels stated an idea is worth nothing and that, in order for an angel to invest, an entrepreneur must have something that is inherently valuable (e.g. existing customers). Entrepreneurs, therefore, need to be realistic before they approach a business angel.

In terms of business strategy factors, realistic expectations were most relevant to an analysis of the market. Angels expect entrepreneurs, who are often optimistic (Landier and Thesmar, 2009), to have a realistic view of the potential of the business, particularly for scaling into international markets, level of competition and market size. Participant 3 noted ‘you can get entrepreneurs who come to you with a product and try to tell you that everyone will want to buy it’. Further to this is the need to be realistic about time frames for success. Participant 12 eloquently explains, ‘you've got to remember, everything takes three times longer, especially the money part’. There is, however, some evidence to suggest that optimism in an entrepreneur may play a positive role in financing of their business. Contrary to the interviewed angels’ view that optimism produces a dangerous bias, there is some research that suggests optimistic entrepreneurs are better at obtaining financing, often at lower cost (Dai et al., 2017).

Further, there is the issue of an angel's own realistic expectations. Interviewees noted that when assessing a business, it is important not to ‘fall in love’. The optimism and enthusiasm of an entrepreneur can be infectious and create a bias. Angels and corroborating participants emphasised the importance of being realistic about whether their own experiences are relevant and useful. In other words, angels must be honest about their own ability to add value to a business. While the issue of optimism has been explored within the finance literature with evidence that optimistic entrepreneurs are not rationed by lenders (Dai et al., 2017), there is little research of the effects of entrepreneurial optimism on business angels. This is a potentially interesting, if challenging, avenue for future research.

5 Conclusion

Tracey Beikoff was lucky – she made her way onto a successful television program and presented her business to angels with the financial resources and, most importantly, the experience and connections, to help grow her business. Before appearing on Shark Tank, she was on the verge of closing down. How many entrepreneurs try, and fail, to find an interested business angel?

This research presents insights into the initial investment decision-making process of business angels in the Australian market. We use evidence from business angels and corroborate this with interviews from other actors to answer the question ‘what underlying drivers influence business angels during the investment decision-making process?’ The answer is presented according to four themes: personal experience, trust, the need to contribute and realistic expectations. By evaluating and corroborating responses, we argue that these themes influence the entire decision-making process, rather than being relevant to a single stage. Additionally, we argue that investment criteria are not limited to consideration at a particular stage but are relevant to the entire decision-making process.

We identify four key lessons from this research experience. First, the use of qualitative research as a method in finance has several benefits. Effective interviewing, supported by corroborating evidence, produces valuable and nuanced results that are difficult, if not impossible, to identify using quantitative methods. Second, angels are difficult to identify (a well-established problem) but techniques such as snowballing yield little in the way of results. This is particularly true with markets containing ‘ego’ investors. Angel investors appear loathe to provide additional contacts, suggesting that their angel network is perhaps weak. The reticence to pass on contacts, or to refer, is concerning, not just for researchers, but for entrepreneurs who may spend time pursuing something that will not produce results. These weaknesses in personal and professional networks complicate the already difficult challenge of raising growth finance.

Third is the failure to address adequately the problem of accessing angel finance. Though formal angel networks exist, and pitch events are frequent, these networks and functions are not necessarily a good way to raise capital. While deal flow exists for angels operating in these environments, it seems that deals do not originate from these environments, and therefore, entrepreneurs may be wasting their time going directly to formal networks to find angel financing – calling into question the value these organisations bring to the ecosystem. The importance angels place on referees during deal origination means that entrepreneurs must develop trusting relationships to potentially access an angel. However, an angel may not be present in an entrepreneur's network. This ‘market organisation’, for want of a better term, is worth further investigation and requires government intervention to address the deficiency in the Australian model.

Finally, the need to contribute is an overwhelming driver for business angels and this is a double-edged sword. It is not simply enough to access a business angel and present a sound business plan. Entrepreneurs need the right angel – one who can bring something other than money. Likewise, angels are looking for businesses who can benefit from their experience and offer them the ability to add value. Identifying angels is difficult; for many entrepreneurs, identifying the right angel is almost impossible. We must look for more structured ways of addressing the disconnect between entrepreneurs and angels.

In terms of future research, five potential avenues of future research present themselves from the findings of this paper. First, the changing nature of business angels. Future research should investigate the prominence of diversification as well as its impact on the nature of angel investors – for example, whether it hinders post-investment involvement or whether this approach effectively manages risks. It should also consider the characteristics of angels ranging from the traditional, high net worth angels, to ‘working’ angels, challenging the definition of an angel investor. Adding further support to this call is the introduction of new technology and the emergence of angel groups (see White and Dumay, 2017). An examination of the prevalence and effectiveness of diversification as a risk management strategy and the relevance of angel networks will add to our knowledge of risk management and, most importantly, will address the problems associated with attempting to raise capital via angel networks.

Second, the issue of sweat equity warrants further investigation. While this research did not aim, nor expect, to discuss sweat equity, its prominence as an issue raised during interviews highlights a need for further investigation. A number of questions arise here: can sweat equity investors be legitimately called angel investors (as they call themselves) and, if so, what are the implications for the definition? What is the prevalence of sweat equity and how do these investors realise a return? How do entrepreneurs view sweat equity?

Third, the combination of the changing nature of business angels and the emergence of sweat equity give rise to the need to update the research on angel typologies (for an overview, see White and Dumay, 2017). The diversity of angel investors, as well as the influence of successful programs such as Shark Tank, raises the question of definition. The presence of investors no longer fitting the traditional definition of a business angel provides an opportunity to extend and add to existing angel typologies (for example, see Szerb et al., 2007). The key question for researchers is what are the different types of angel investors in today's market?

Fourth, the issue of the value of pitch events as a means of raising capital represents an opportunity to expand our existing knowledge. The interviewed angels questioned the value of pitch events, noting that they are networking opportunities, rather than a source of deals. Investigation into the efficacy of pitch events is warranted and will have significant benefits and implications for researchers, entrepreneurs, angels, incubators and governments.

Fifth, though not the purpose of this research, using corroborating participants highlighted some inconsistences and challenges for the angel finance market, its structure, governance and policy making. While the corroborating participants were able to verify and validate aspects of what angel investors said, there was also a disconnect between the participants – particularly angels and government policy makers. An investigation into the organisation of the marketplace, and development of the understanding of context would be beneficial and provide researchers with an opportunity to influence government policy aimed at building entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Like all studies, this research is subject to limitations. The first limitation concerns the types of questions used when interviewing corroborating participants. This research investigates the angel investing phenomenon with business angels the subject of the research. Interviewing other participants requires careful consideration of questions that effectively corroborate angel responses. For example, a person responsible for the development of government policy may have a different understanding of angel financing and view it from a different context. This is evident where, for example, a government participant was responsible for developing an incubator and thus has limited contact with business angels. In order to address this, the interviewer must either add explanation to questions, potentially biasing the response by leading the interviewee, or change the nature of the question.

The different angel typologies create a second limitation. The presence of different business angels, with different approaches to the market and different contextual understandings, creates a potential bias in responses. For example, prospective participants who present themselves as angel investors may, in fact, be sweat equity investors, thus calling into question the validity of their responses. Participants raised sweat equity as a legitimate form of angel investing, and, as such, it is difficult to rule out some of the participants for being sweat equity investors, rather than fitting the traditional definition. Further, the population of angel investors is heterogeneous, but using techniques to identify them, such as snowballing, has the potential to homogenise the population.