Political connections, auditor choice and corporate accounting transparency: evidence from private sector firms in China

Abstract

This article investigates the way in which political connections impact auditor choice. Using a political connection index constructed based on the bureaucratic ranks of executive managers and board members in Chinese private sector firms, we find that for firms with weak political connections, the likelihood of hiring high-quality auditors increases with the degree of political connectedness, while it decreases with political connectedness for firms with strong political connections. This inverse U-shaped relationship is particularly pronounced for firms with ownership structures that intensify agency problems. Finally, we find that political connections and accounting transparency also have an inverse U-shaped relationship.

1 Introduction

The literature on accounting ethics shows that political connections have a great impact on listed firms' auditor choice and accounting transparency, but presents conflicting findings about the direction of the effect. On the one hand, corporate insiders in connected firms have a strong incentive to extract benefits from political connections to at least recover their costs incurred in developing these connections (Morck et al., 2000; Srinidhi et al., 2012). In fact, Qian et al. (2011) find that corporate resources expropriated by corporate insiders in connected firms exceed the costs of building political connections. Consequently, connected firms may be less eager to engage high-quality auditors, as the strict monitoring imposed by high-quality auditors and the associated accounting transparency limit corporate insiders' abilities to divert corporate resources away from outside investors (Chaney et al., 2011).

On the other hand, connected firms may have strong incentives to alleviate the severe agency conflicts arising from political connections and thus may favour high-quality auditors and great accounting transparency compared with non-connected firms. Guedhami et al. (2014) document that corporate insiders in connected firms are more likely to choose a Big 4 auditor than are other firms, in order to signal to outside investors that they refrain from expropriating minority shareholders. There is evidence that high-quality auditors, through their strict monitoring, can help improve accounting transparency (Watts and Zimmerman, 1983), which in turn helps protect investors' interests, thereby reducing agency costs in connected firms (Dyck and Zingales, 2004). For example, Fan and Wong (2005) find that the appointment of high-quality auditors mitigates share price discounts associated with the agency problem induced by incentive misalignment.

In this article, we are interested in exploring the conditions under which corporate insiders' incentives to derive benefits from political connections dominate their incentives to reduce agency costs, thereby leading to a low demand for high-quality auditors and accounting transparency, and the conditions under which the opposite is true. Prior research in this area primarily examines auditor choice and accounting transparency for connected firms compared with those for non-connected firms. However, the strength and intensity of political connections vary across connected firms and may play an important role in explaining the way in which political connections impact auditor choice and accounting transparency. This notion reflects the fact that both the potential benefits derived from political connections and agency costs induced by political connections vary with the degree of political connectedness. We conjecture that compared with non-connected firms, firms with relatively weak political connections prefer to hire high-quality auditors and become more transparent, in order to obtain the great benefits brought about by high-quality audits and accounting transparency. On the other hand, firms with strong political connections may be more likely to shun high-quality auditors, so that corporate insiders are better able to divert the potentially great benefits of these particularly strong political connections away from outside investors.

China's governmental and economic environment presents an excellent case for us to understand our research issues and test our conjectures. First, the unique Chinese bureaucratic ranking system enables us to exploit the variation in political connectedness across connected firms. Under China's multilevel administrative system, every public organisation or government official is granted a bureaucratic rank. Each rank has more power than the ranks beneath it. In particular, China's administrative hierarchy consists of five levels of government: the central, provincial, prefectural, county and township. Correspondingly, bureaucratic ranks for government officials from highest to lowest include state leader, minister, deputy minister, bureau director (Ting), deputy bureau director (Fu Ting), county/division head (Chu), deputy county/division head (Fu Chu), township/section head (Ke) and deputy township/section head (Fu Ke). Deputies to the Chinese People's Congress (PC) and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) members at the national, provincial and local administrative levels also have corresponding bureaucratic ranks. Based on the bureaucratic ranks of those corporate executives as well as board members who hold (or used to hold) government positions (or are/were a member of Chinese PC or CPPCC), we are able to measure not only the presence but also the strength of political connections in a firm and further analyse the conjectured nonlinear relationship between the degree of political connectedness and auditor choice.

Second, China is still in the process of transitioning its economy from a centrally planned to a market-oriented economy. This provides an institutional environment that is particularly suited to examining the trade-off between rents arising from political connections and the benefits of accounting transparency for connected firms. Specifically, during this transition period in China, administrative and economic resources are still largely controlled by the government, and firms can derive substantial benefits from political connections in China compared with firms in developed countries. In such an environment, private sector firms, which do not have any state ownership or control, have a particularly strong incentive to build and exploit political connections, as their success is heavily dependent on the awarding of government contracts and other government favours (Srinidhi et al., 2012). As accounting transparency limits the abilities of politicians and corporate insiders to consume their private benefits of control (Piotroski et al., 2015), China's private sector firms may be especially unwilling to hire high-quality auditors and to be transparent. On the other hand, as China's economy becomes more market-oriented, connected firms' demand for high-quality audits and accounting transparency increases, as transparency helps alleviate information asymmetry, reduce the cost of capital, discourage tunnelling activities and improve enterprise value.

We find that political connections and auditor choice exhibit an inverse U-shaped relationship, meaning that the likelihood of choosing high-quality auditors increases with political connectedness for firms with relatively less strong political connections, but decreases with political connectedness for firms with strong political connections. The exogenous event that all China's big audit firms were required to shift from the limited liability partnership form to the special general partnership form is used as a natural experiment to address the endogeneity concerns in our test. We show that after the change in organisational form, for a given degree of political connectedness, the likelihood of choosing high-quality auditors rises further for firms with relatively weak political connections, while the likelihood falls further for firms with strong political connections. Moreover, we demonstrate that the inverse U-shaped relationship is more pronounced for connected firms with ownership structures conducive to tunnelling. As expected, we also detect an inverse U-shaped relationship between political connectedness and accounting transparency, because high-quality audits can help enhance accounting transparency.

The contribution of this article is twofold. First, in contrast with previous studies that measure political connectedness in a dummy manner, we construct a political connection index that can capture the variation in political connectedness across connected firms, and deeply analyse the motives of financial reporting for firms with different degrees of political connectedness. Second, our analysis furthers our understanding of the way in which political connections impact auditor choice and accounting transparency by identifying the role that the degree of political connectedness plays in shaping the relationship. This provides an explanation for the reported conflicting findings in prior research as to how political connections are related to auditor choice and accounting transparency.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows. Section 2 develops the hypotheses to be tested. Section 3 outlines the way in which the major variables are measured and describes the model. Section 4 describes the data and descriptive statistics of regression variables. Section 5 analyses the empirical results, while Section 6 concludes the article.

2 Hypotheses

The conflicting findings in prior research with regard to the impact of political connections on auditor choice reveal that high-quality audits bring both costs and benefits to connected firms. High-quality audits are costly for connected firms, because the strict monitoring imposed by high-quality auditors limits the abilities of controlling shareholders to extract benefits from political connections and to divert corporate resources for private benefit (Chaney et al., 2011; Fan et al., 2011b; Srinidhi et al., 2012; Piotroski et al., 2015). Meanwhile, high-quality audits are also beneficial because they help reduce insiders' discretion to distort financial reporting and mitigate the agency conflicts in connected firms, thereby increasing firms' value (Guedhami et al., 2014).

Clearly, a firm's decision to appoint a high-quality auditor hinges on whether there is a net benefit from high-quality audits. For connected firms, both the marginal benefits and marginal costs of hiring high-quality auditors are affected by the degrees of their political connectedness. If political connections are relatively weak, the benefits derived from these connections are low, which means that the costs of hiring high-quality auditors are low. We predict that for firms with less strong political connections, the benefits of hiring high-quality auditors may outweigh the costs, and thereby, these firms tend to choose high-quality auditors. However, for firms with strong political connections, the incentives of exploiting political connections are particularly strong. This is due to two reasons. First, the potential benefits derived from political connections are greater for firms with strong political connections than for firms with less strong political connections. Second, corporate insiders are better able to expropriate minority shareholders, given the more lenient monitoring from regulators faced by firms with strong political connections (Berkman et al., 2010). Thus, the costs of hiring high-quality auditors could be much higher than its benefits, and thereby, these firms tend to choose low-quality auditors, in order to be better able to distort financial reporting to cover up the expropriation practices arising from political cronyism and corruption (Chaney et al., 2011). We propose the following hypothesis:

- H1: The likelihood of connected firms hiring high-quality auditors increases with political connectedness if the degree of political connectedness is lower than a threshold, while it decreases with political connectedness if the degree of political connectedness is higher than the threshold. Namely, for connected firms, the degree of political connectedness and the likelihood of hiring high-quality auditors exhibit an inverse U-shaped relationship.

The intuition behind Hypothesis 1 is that political connections exacerbate the agency conflicts between corporate insiders and outside investors, thereby influencing auditor choice. It is well documented that firms' ownership structures are highly associated with agency conflicts. For example, firms with a single large shareholder, firms with high-control concentration, as well as those with a high degree of separation between control and cash flow rights typically suffer severe agency problems, as controlling shareholders in these firms have high power and incentives to expropriate minority shareholders (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; Guedhami et al., 2014). We expect that the ownership structures that intensify agency conflicts will further strengthen a firm's incentive for mitigating agency problems if the degree of political connectedness is low, while they will further strengthen the firm's incentive for deriving benefits from political connections if the degree of political connectedness is high. We propose the following hypothesis:

- H2: The inverse U-shaped pattern between political connectedness and the choice of high-quality auditors is more pronounced for firms with ownership structures that intensify agency conflicts with outside investors.

Political connections are associated with auditor choice in connected firms, which in turn is related to accounting transparency. High-quality auditors are able to supply better monitoring than low-quality auditors, which helps improve accounting transparency. In prior research, the competing views about the impact of political connections on auditor choice imply that the views about the impact on reporting transparency are also controversial. For example, Srinidhi et al. (2012) find that connected firms exhibit more earnings management and lower transparency than other firms, whereas Guedhami et al. (2014) show that the opposite is true. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, we propose the following hypothesis:

- H3: Accounting transparency increases with political connectedness if the degree of political connectedness is lower than a threshold, while it decreases with political connectedness if the degree of political connectedness is higher than the threshold. Namely, the relationship between a firm's degree of political connectedness and accounting transparency exhibits an inverse U-shaped pattern.

3 Research methodology

3.1 Measuring the degree of political connectedness

In previous studies, a firm is classified as having political connections if one or more of its executives (executive managers or board members) are politically connected. Following the literature, an executive manager or a board member in Chinese firms is considered politically connected, if he/she currently holds (or used to hold) a government position or if he/she is (or was) a deputy to a Chinese PC or a CPPCC member (Chen et al., 2011; Li and Qian, 2013; Du et al., 2014).1

To gauge the strength and intensity of political connections for Chinese private sector firms, we follow Chen et al. (2013) and Fisman (2001) and construct a political connection index. To this end, we first identify politically connected executives, based on the information on the personal career background of executive managers and board members, which is manually collected from annual reports of private sector firms. Then, we assign scores to the connected corporate executives, according to their bureaucratic ranks, with high connection scores associated with high bureaucratic ranks. Under the Chinese bureaucratic system, bureaucrats with a high rank have more political power and greater access to political and economic resources. Thus, the bureaucratic ranks of corporate executives provide a measure of the degree of their political connectedness. Table A1 in Appendix describes details about the points that each bureaucratic rank earns. If a corporate executive (executive manager or board member) holds (or used to hold) multiple government positions (or is or used to be a Chinese PC/CPPCC member at different levels), only the highest bureaucratic rank is considered when assigning connection scores. If a corporate executive holds (or used to hold) a government position and is (or was) also a deputy to a Chinese PC or a CPPCC member, then the total scores earned by this executive are the sum of the scores for his/her government position and PC/CPPCC membership. Table A2 in Appendix presents the descriptive statistics of political connection scores of corporate executives and board members by positions.

Third, the total score each firm achieves is simply the sum of the points that all of its connected executive managers and board members earn. The summary statistics of the scores that firms achieve are reported in Table A3 in Appendix. We find that the minimum score is zero, which indicates that there are no political connections, and the highest score is 55. This wide range of connection scores reflects the great variation in political connectedness in Chinese connected firms. Finally, we obtain the political connection index by standardising these scores using the maximum difference method. Precisely, the connection index for firm i is defined as the difference between connection points it obtains and the minimum connection points in a given year divided by the difference between the maximum and minimum points in the sample in the year.

3.2 Measuring the quality of auditors

Most prior research uses auditor size as a proxy for auditor quality and classifies the international Big 4 auditors as having high quality. However, in China, the Big 4 market share is only about 5 percent. Following Srinidhi et al. (2012) and Yang (2013), in this paper, we define Big 4 auditors and those that are among the top-10 domestic auditors in all years in our sample period as high-quality audit firms. These top-10 domestic firms are identified based on the annual comprehensive evaluation and ranking of audit firms published by the Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants (CICPA), which are downloaded from the CICPA website.

3.3 Measuring accounting transparency

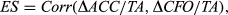

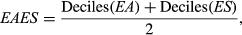

Accounting transparency is defined as the degree to which a firm's reported accounting earnings reflect its true economic earnings and can be measured by earnings aggressiveness (EA), loss avoidance and earnings smoothing (ES) (Bhattacharya et al., 2003). As loss avoidance is a transparency measure at the country level, in this paper, we use EA and ES as proxies for accounting transparency.

(1)

(1) (2)

(2) (3)

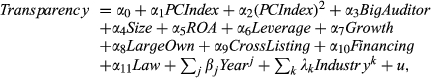

(3)3.4 Regression models

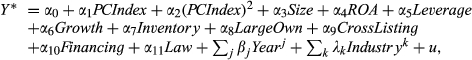

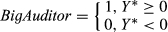

(4)

(4)

BigAuditor = 1 means that a firm hires a high-quality auditor, and BigAuditor = 0 means that the firm hires a low-quality auditor. In Equation 4, PCIndex is the political connection index used to measure the degree of political connectedness for a firm.

To control for the effects of a firm's characteristics on auditor choice, we include the following firm-level characteristics: firm size (Size), which is measured by the natural logarithm of total assets; performance (ROA), which is the return on assets; degree of leverage (Leverage), which is measured by the ratio of total liabilities to total assets; growth (Growth), which is measured by the sales growth rate; asset structure (Inventory), which is measured by the ratio of inventory to total assets; ownership structure (LargeOwn), which is measured by the proportion of total shares held by the largest shareholder; and level of financing activities, which is captured by two dummy variables: the dummy variable CrossListing taking the value of 1 if shares are cross-listed in the A-share market and other markets (B-share market, Hong Kong or overseas markets) and the dummy variable Financing taking the value of 1 if the firm raises equity capital in a given year.

We also include in the model the legal environment variable Law, which is proxied by the regional legal environment index constructed by Fan et al. (2011a).2 Finally, we include the dummy variable Yearj to control for the time effect, as well as the dummy variable Industryk aimed at controlling for the industry effect.

To test Hypothesis 1, we run Regression 4 using the full sample. If the estimated coefficient α1 is significantly positive and the coefficient α2 is significantly negative, then Hypothesis 1 is true. To test Hypothesis 2, following Guedhami et al. (2014), we divide the sample into two subsamples, based on whether or not there is separation between the largest shareholders' control rights and ownership rights, whether or not the controlling shareholders' control rights exceed 30 percent,3 and whether or not there is a single large shareholder in firms. Then, we rerun Regression 4. If Hypothesis 2 is true, then the size and significance of both the estimated coefficients α1 and α2 are more pronounced in the subsamples of firms with a wedge between control and ownership rights, with a high-control concentration and with a single large shareholder.

(5)

(5)4 Data and descriptive statistics

4.1 Sample

Our sample period extends from January 2004 to December 2012. The sample period starts with 2004, because since 2004, all Chinese listed firms are required by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (the CSRC) to disclose in annual reports biographical information on executive managers and board members, including educational background, work experience, positions held in the government and membership in the national and local Chinese PCs as well as CPPCCs, among others. Following Srinidhi et al. (2012), we consider all listed A-share companies that operate in the private sector, and exclude from our sample China's partially privatised state-owned enterprises (SOEs), because political connections in both types of firms are established in different manners and may serve distinct goals. In particular, political connections of SOEs are established naturally by government authority to serve its political purposes (Fan et al., 2007), while private sector firms build their political connections on their own initiative in order to exploit political connections to secure government contracts and privileges (Chen et al., 2011).

Starting with the initial sample, we exclude companies with missing information on the degree of separation between control and cash flow rights, ownership characteristics, political connections and accounting transparency. The Growth Enterprise Market (GEM) listed companies are also excluded, as the GEM was established in 2009, and the data sample period for the GEM listed firms is not long enough for our research, especially for calculating the measures of accounting transparency. We end up with a total of 3640 firm-year observations. To prevent extreme observations from influencing our results, the values of our variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. We obtain the accounting data of listed firms for our sample period from the Wind database and obtain the data on ownership from China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. Measures for the regional institutional environment are obtained from Fan et al. (2011a).

4.2 Descriptive statistics of regression variables

Panel A of Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics for all the variables used in both regressions. We notice that the market share of the Big 4 as well as those that are among top-10 domestic audit firms in all years is only 17 percent, indicating a lack of demand for high-quality audit services in Chinese private sector firms. The mean of the political connection index is 0.1074 with a standard deviation of 0.1007. The average proportion of total shares held by the largest shareholder is 32 percent, while the average ultimate control rights held by controlling shareholders are 34 percent. This suggests that agency conflicts in the firms are pervasive, which might influence firms' auditor choice. The average EA and ES are 0.1165 and −0.2555, respectively. This implies that accounting transparency is on average low for our sample firms.

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics of variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | Mean | Standard deviation | Min. | Max. | |

| BigAuditor | 3640 | 0.1701 | 0.3757 | 0 | 1 |

| PCIndex | 3640 | 0.1074 | 0.1007 | 0 | 0.4182 |

| Size | 3640 | 21.1463 | 1.0582 | 16.8306 | 25.0561 |

| ROA | 3640 | 0.0658 | 0.0858 | −0.2991 | 0.3548 |

| Leverage | 3640 | 0.5062 | 0.3038 | 0.0071 | 2.2379 |

| Growth | 3640 | 0.2280 | 0.5329 | −0.8196 | 2.7267 |

| Inventory | 3640 | 0.1912 | 0.1660 | 0 | 0.7954 |

| LargeOwn | 3640 | 0.3221 | 0.1395 | 0.0811 | 0.6800 |

| CrossListing | 3640 | 0.0250 | 0.1561 | 0 | 1 |

| Financing | 3640 | 0.1486 | 0.3558 | 0 | 1 |

| Law | 3640 | 8.8990 | 3.7039 | 2.5467 | 15.2350 |

| EA | 3637 | 0.1165 | 0.1285 | 0.0001 | 0.6633 |

| ES | 411 | −0.2555 | 0.4745 | −0.9498 | 0.8413 |

| EAES | 2790 | 4.4887 | 2.0830 | 0 | 9 |

| Panel B: Correlations among independent various | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCIndex | Size | ROA | Leverage | Growth | Inventory | LargeOwn | CrossListing | Financing | Law | |

| PCIndex | 1 | |||||||||

| Size | 0.1150 | 1 | ||||||||

| ROA | 0.0045 | 0.1600 | 1 | |||||||

| Leverage | 0.0359 | −0.0118 | −0.3278 | 1 | ||||||

| Growth | 0.0134 | 0.1112 | 0.2773 | 0.0037 | 1 | |||||

| Inventory | 0.0721 | 0.2939 | 0.0148 | 0.1556 | 0.1133 | 1 | ||||

| LargeOwn | 0.0458 | 0.2354 | 0.1604 | −0.0713 | 0.1129 | 0.1747 | 1 | |||

| CrossListing | 0.0189 | 0.0688 | −0.0028 | 0.0177 | −0.0122 | −0.0529 | −0.0354 | 1 | ||

| Financing | −0.0232 | 0.0626 | 0.2177 | −0.1511 | 0.1691 | −0.0178 | 0.1151 | −0.0422 | 1 | |

| Law | −0.0502 | 0.1249 | 0.1360 | −0.0946 | 0.0142 | 0.0850 | 0.1367 | 0.0299 | 0.0808 | 1 |

- Panel A of this table reports the descriptive statistics of all variables in our model, while Panel B reports the correlation matrix of all independent variables in the regression models. BigAuditor is set equal to 1, if a firm is either a top-10 domestic auditor in all years or a Big 4 auditor, based on the comprehensive evaluation and ranking by the CICPA, and 0, otherwise. PCIndex is a firm's political connection index constructed based on the bureaucratic ranks of corporate executives and board members who hold (or used to hold) government positions or who are (or were) a deputy to a Chinese PC or a CPPCC member. Size is the natural logarithm of total assets. ROA is the return on asset. Leverage is the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. Growth is the sales growth rate. Inventory is the ratio of inventory to total assets. LargeOwn is the proportion of total shares held by the largest shareholder. CrossListing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if shares are cross-listed in A-share market and other markets, and 0, otherwise. Financing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if the firm raised equity capital in a given year, and 0, otherwise. Law is a variable representing the regional legal environment index. EA, ES and EAES are the measures of accounting transparency used in this paper, which are calculated by Equations 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Panel B of Table 1 presents the average correlations among the explanatory variables. We can see that most of these correlations are generally low, with the exception that the correlation between the variables Inventory and Size and the correlation between the variables Growth and ROA are both about 0.3. Therefore, there is no serious multicollinearity among the factors considered in our model.

5 Empirical results

5.1 Political connections and auditor choice

To evaluate the link between political connections and auditor choice, we estimate Regression 4 using the full sample and present the results in the first column of Table 2. The results show that the estimated coefficient on the variable PCIndex is significantly positive, while the coefficient on (PCIndex)2 is significantly negative, suggesting that the plot of the likelihood of firms hiring a high-quality auditor as a function of the degree of their political connectedness is an inverse U-shaped curve. This provides compelling evidence in favour of Hypothesis 1 that links political connections and auditor choice. More specifically, if the degree of political connectedness is lower than a threshold, then these connected firms have particularly strong incentives to reduce agency costs arising from information asymmetry. In this case, connected firms with a high degree of political connectedness are more likely to hire a high-quality auditor to improve accounting transparency than are firms with a low degree of connectedness. This extends Guedhami et al.'s (2014) finding that politically connected firms are more likely to appoint a Big 4 auditor than are non-connected firms. However, if the degree of political connectedness is higher than the threshold, then these connected firms have stronger incentives to exploit political benefits and expropriate minority shareholders. In this case, firms with a high degree of political connectedness are more eager to engage low-quality auditors to better conceal their tunnelling practices. This finding corroborates the findings by Chaney et al. (2011) and Srinidhi et al. (2012).

| Variables | Base model | Model with natural experiment |

|---|---|---|

| PCIndex | 3.1511** | 7.2794*** |

| (2.51) | (4.08) | |

| (PCIndex)2 | −7.5505** | −13.2490*** |

| (−2.09) | (−3.04) | |

| PCIndex×SGP | −5.3619** | |

| (−2.14) | ||

| (PCIndex)2×SGP | 6.9421 | |

| (1.07) | ||

| SGP | 0.9131*** | |

| (4.77) | ||

| Size | 0.1483*** | 0.1246** |

| (2.95) | (2.26) | |

| ROA | −0.7556 | −1.1595 |

| (−1.09) | (−1.43) | |

| Leverage | −0.1243 | −0.0379 |

| (−0.60) | (−0.16) | |

| Growth | −0.0154 | 0.0418 |

| (−0.15) | (0.37) | |

| Inventory | 1.1130*** | 1.1299*** |

| (3.00) | (2.74) | |

| LargeOwn | −0.7218** | −1.0547*** |

| (−2.05) | (−2.64) | |

| CrossListing | 1.2084*** | 0.9112*** |

| (5.09) | (2.94) | |

| Financing | 0.0706 | −0.0924 |

| (0.52) | (−0.58) | |

| LAW | 0.1120*** | 0.1063*** |

| (8.47) | (7.03) | |

| Constant | −5.2484*** | −5.3915*** |

| (−4.89) | (−4.70) | |

| Industry | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | / |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0786 | 0.0602 |

| Chi square | 260.98*** | 148.05*** |

| Observations | 3640 | 2436 |

- This table reports the estimation results for Regression 4, in which the explained variable Y* is a latent variable. BigAuditor = 1 if Y* ≥ 0, and BigAuditor = 0 if Y* < 0. BigAuditor is set equal to 1, if a firm is either a top-10 domestic auditor in all years or a Big 4 auditor, based on the comprehensive evaluation and ranking by the CICPA, and 0, otherwise. PCIndex is a firm's political connection index constructed based on the bureaucratic ranks of corporate executives and board members who hold (or used to hold) government positions or who are (or were) a deputy to a Chinese PC or a CPPCC member. SGP is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if the observations are from 2011, 2012 and 2013, and takes the value of 0, if they are from 2008, 2009 and 2010. Size is the natural logarithm of total assets. ROA is the return on assets. Leverage is the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. Growth is the sales growth rate. Inventory is the ratio of inventory to total assets. LargeOwn is the proportion of total shares held by the largest shareholder. CrossListing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if shares are cross-listed in A-share market and other markets, and 0, otherwise. Financing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if the firm raised equity capital in a given year, and 0, otherwise. Law is a variable representing the regional legal environment index. Z statistics are in parentheses. ***, ** and * represent significance at the 1, 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively.

We also find some significant results for the control variables in the regression. Consistent with the findings by Srinidhi et al. (2012) and Guedhami et al. (2014), we find that the coefficient on the variable Size is positive and significant at the 1 percent level, indicating that large firms are more likely to choose high-quality auditors. We also find that the coefficient on the variable Inventory is positively significant, which is in sharp contrast with the findings by Guedhami et al. (2014). One possible reason for this result is that Chinese firms generally do not manage earnings through inventory manipulation, and thus, a high inventory level does not necessarily imply a high audit risk (Wang et al., 2008). Note that the coefficient on the variable LargeOwn is significantly negative. It follows that as the proportion of total shares held by the largest shareholder increases, the likelihood that firms hire a high-quality auditor falls. This is because corporate insiders in firms with a larger percentage of total shares held by the largest shareholder are better able to divert corporate resources for private benefit and thus have a stronger incentive to shun high-quality auditors in order to better obscure the variability in the economic performance. In addition, our results show that the coefficient on the variable CrossListing is positive and significant, suggesting that cross-listed firms are more likely to hire high-quality auditors. Finally, we find that firms located in regions with stronger legal environments exhibit greater demand for high-quality audit services, as the coefficient on the variable Law is positive and significant. However, the estimate coefficients on ROA, Leverage, Growth and Financing are all insignificant.

We next perform two robustness checks. First, to address the potential endogenous problems in our model due to possible reverse causality or omitted variables that affect both political connections and auditor choice, we divide our sample period into two subperiods: the periods before and after the change in the partnership form of audit firms. Almost all of the big audit firms completed shifting from the limited liability partnership (LLP) form to the special general partnership (SGP) form after 2011, as required by the Ministry of Finance and State Administration for Industry and Commerce of China. The special general partnership form can help strengthen co-partners' legal responsibilities. In fact, Wang and Lu (2014) and Liu et al. (2015) document that, after the implementation of SGP, the audit quality of big auditors is substantially improved and thereby can better protect the interests of investors in the firms audited. For these reasons, we expect this exogenous event to impact the relationship between political connections and auditor choice detected by our model.

In this exercise, we define the dummy variable SGP to differentiate the effects of political connections on auditor choice before and after the change in the organisational form in an audit firm. More specifically, the variable SGP takes the value of 1 if the sample observations are from 2011, 2012 and 2013, and it takes the value of zero if the observations are from 2008, 2009 and 2010.4 We include both interaction terms PCIndex × SGP and (PCIndex)2 × SGP in Regression 4, and rerun this extended regression. The estimation results of this augmented regression are also reported in Table 2. Consistent with the estimation results for the base model, we find that the coefficient on PCIndex is positive and significant, and the coefficient on (PCIndex)2 is negative and significant. However, we find that the estimated coefficient on the interaction term PCIndex × SGP is significantly negative, while the coefficient on (PCIndex)2 × SGP is insignificant. This suggests that after the change in the organisational form, the size of the coefficient on PCIndex is reduced (but still positive), whereas the coefficient on (PCIndex)2 × SGP remains the same as before. This implies that after the change in the organisational form, the likelihood of choosing high-quality auditors rises further for firms with low political connectedness, while the likelihood falls further for firms with strong political connections. To understand this finding, we take firms with weak political connections as an example. On the one hand, after the implementation of SGP, hiring high-quality auditors can further reduce insiders' discretion to distort financial reporting and better mitigate the agency problem in connected firms. On the other hand, as the benefits derived from political connections are relatively low for these firms, the costs of hiring high-quality auditors do not increase significantly.

Our second robustness check is to examine whether the way in which the key variables are measured biases our results. First, we construct several alternative political connection indices (PCIndex_Robust) to measure the degree of firms' political connectedness, based on various calculation methods for the scores earned by connected executive managers or board members in a firm. These alternative measures are described as follows.

- To examine whether the method of assigning connection scores to various bureaucratic ranks impacts our main findings, we reconstruct our political connection index by combining Ting and Fu Ting, Chu and Fu Chu, Ke and Fu Ke and assigning these combined bureaucratic ranks political connection scores of 6, 4 and 2, respectively.

- As compared with government officials at the same bureaucratic rank, members of PC and CPPCC may have low political power and low capability of obtaining political and economic resources, we use the following two methods to recalculate our political connection index. The first is that we lower the scores for PC and CPPCC members at the national, provincial and local/city levels to 5, 3 and 1, respectively, while keeping the scores for government officials unchanged. The second is that we exclude PC and CPPCC members from the political connection group, and measure firms' political connections based solely on the bureaucratic ranks of the corporate executives and board members who currently hold (or used to hold) a government position.

- As the Chinese government uses a quota system to control the overall size of the IPO market, data show that almost all the listed private sector firms in China operate at the provincial level or above. For these firms, political connections at the local or city level impact their sales and operations in a particular region only (Lu, 2011) and thus are less valuable than political connections at the provincial or national level. For this reason, we exclude political connections at the county as well as local/city levels and recalculate our political connection index based on the bureaucratic ranks of the corporate executives and board members who currently hold (or used to hold) a government position at or above the Fu Ting level, as well as based on the ranks of those executives who are/were a member of Chinese PC or CPPCC at or above the provincial level.

- Given that independent directors have limited influence on a firm's day-to-day operations, we follow Liang and Feng (2010) and exclude connected independent directors when measuring the firm's political connections. In the previous analysis, we do not exclude connected independent directors, as independent directors may also help firms obtain economic resources, while their role in monitoring the management of Chinese private sector firms is generally weak (Du et al., 2014; Xie and Yi, 2014).

- Because the strength of political connections is measured by the total scores that all executive managers and board members earn in a firm, board size will affect the total score value. To reduce this size effect, we standardise the political connection index by dividing the total scores by the total number of executive managers and board members in the firm.

- Our main focus is on the relation between auditor choice and the strength of political connections in a firm. As a comparison, we also examine how the presence of political connections in a firm impacts its auditor choice. To this end, we code a firm's political connection as a binary indicator variable, setting it equal to one in years when an executive manager or board member currently holds (or used to hold) a government position at the Chu level and above, or is (or was) a deputy to the Chinese PC or a CPPCC member at provincial level and above.

Second, following Srinidhi et al. (2012), we use an alternative ranking of audit firms, which is based on the market share of total assets audited, to identify high-quality auditors. More specifically, the variable BigAuditor_Robust is set equal to 1, if a firm is either a top-10 domestic auditor in all years during the sample period or a Big 4 auditor, and 0, otherwise.

Third, following Fan and Wong (2005), we use the proportion of voting rights held by the largest ultimate owner of a firm to capture the effect of ownership structures on auditor choice. We finally rerun our regression using each of these alternative measures in the model and report the results in Table 3. Overall, these results reconfirm our previous finding about the inverse U-shaped relationship between the likelihood of choosing high-quality auditors and the degree of political connectedness in Chinese private sector firms. In addition, we find that the estimated coefficient on the political connection dummy variable is positive and significant at the 1 percent level, suggesting that firms with political connections are generally more likely to hire high-quality auditors than are other firms.

| Variables | Alternative measure of political connectedness | Alternative measure of auditor quality | Alternative measure of ownership characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |||

| PCIndex | 4.1468*** | 3.0591** | |||||||

| (3.20) | (2.42) | ||||||||

| (PCIndex)2 | −9.8584*** | −7.1680** | |||||||

| (−2.62) | (−1.97) | ||||||||

| PCIndex_Robust | 2.7362** | 3.0316** | 2.4764** | 4.9433*** | 2.9612** | 1.4553** | 0.3661*** | ||

| (2.23) | (2.41) | (2.39) | (3.97) | (2.07) | (2.21) | (3.87) | |||

| (PCIndex_Robust)2 | −6.4056* | −7.3206** | −6.2237** | −14.3099*** | −12.4948** | −1.8344* | |||

| (−1.85) | (−2.00) | (−2.21) | (−3.36) | (−2.26) | (−1.78) | ||||

| Size | 0.1507*** | 0.1490*** | 0.1547*** | 0.1448*** | 0.1581*** | 0.1496*** | 0.1353*** | 0.1512*** | 0.1296** |

| (3.00) | (2.97) | (3.10) | (2.89) | (3.12) | (3.00) | (2.72) | (2.86) | (2.56) | |

| ROA | −0.7426 | −0.7462 | −0.7189 | −0.8716 | −0.8039 | −0.7691 | −0.7920 | −0.9108 | −0.7887 |

| (−1.07) | (−1.08) | (−1.04) | (−1.25) | (−1.15) | (−1.11) | (−1.14) | (−1.24) | (−1.10) | |

| Leverage | −0.1258 | −0.1292 | −0.1473 | −0.0872 | −0.1225 | −0.1208 | −0.1178 | −0.3056 | −0.1940 |

| (−0.60) | (−0.62) | (−0.71) | (−0.42) | (−0.59) | (−0.58) | (−0.57) | (−1.30) | (−0.88) | |

| Growth | −0.0169 | −0.0162 | −0.0207 | −0.0020 | −0.0199 | −0.0177 | −0.0103 | −0.0308 | −0.0060 |

| (−0.17) | (−0.16) | (−0.20) | (−0.02) | (−0.20) | (−0.17) | (−0.10) | (−0.29) | (−0.06) | |

| Inventory | 1.1105*** | 1.1167*** | 1.0740*** | 1.1821*** | 1.1058*** | 1.1147*** | 1.1157*** | 1.1619*** | 1.1520*** |

| (2.99) | (3.01) | (2.89) | (3.17) | (2.98) | (3.00) | (3.00) | (2.97) | (3.06) | |

| LargeOwn | −0.7148** | −0.7219** | −0.6648* | −0.7717** | −0.6854* | −0.7278** | −0.7755** | −0.0898 | |

| (−2.03) | (−2.05) | (−1.89) | (−2.19) | (−1.95) | (−2.06) | (−2.20) | (−0.25) | ||

| ControlRights | −0.0062* | ||||||||

| (−1.89) | |||||||||

| CrossListing | 1.1994*** | 1.1988*** | 1.2061*** | 1.1788*** | 1.1722*** | 1.2229*** | 1.1736*** | 1.3671*** | 1.2411*** |

| (5.06) | (5.06) | (5.10) | (4.94) | (4.93) | (5.11) | (4.93) | (5.71) | (5.20) | |

| Financing | 0.0699 | 0.0724 | 0.0693 | 0.0857 | 0.0609 | 0.0759 | 0.0836 | 0.0667 | 0.0719 |

| (0.52) | (0.54) | (0.52) | (0.64) | (0.45) | (0.56) | (0.62) | (0.49) | (0.53) | |

| LAW | 0.1117*** | 0.1122*** | 0.1122*** | 0.1127*** | 0.1117*** | 0.1116*** | 0.1150*** | 0.1393*** | 0.1142*** |

| (8.44) | (8.47) | (8.45) | (8.50) | (8.44) | (8.44) | (8.67) | (10.05) | (8.50) | |

| Constant | −5.2860*** | −5.2478*** | −5.3236*** | −5.1270*** | −5.3707*** | −5.2466*** | −5.0181*** | −5.8663*** | −4.9075*** |

| (−4.92) | (−4.90) | (−4.99) | (−4.80) | (−4.98) | (−4.93) | (−4.73) | (−5.23) | (−4.53) | |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0782 | 0.0784 | 0.0784 | 0.0814 | 0.0785 | 0.0781 | 0.0811 | 0.0887 | 0.0810 |

| Chi square | 259.54*** | 260.40*** | 260.36*** | 270.36*** | 260.71*** | 259.41*** | 269.33*** | 282.45*** | 264.61*** |

| Observations | 3640 | 3640 | 3640 | 3640 | 3640 | 3640 | 3640 | 3535 | 3563 |

- This table reports the estimation results for Regression 4, in which auditor quality, political connectedness and ownership characteristics are measured using different methods. The explained variable Y* is a latent variable. In the case, where the alternative measure of auditor quality is used in the regression, then Y* is defined as follows. BigAuditor_Robust = 1 if Y* ≥ 0, and BigAuditor_Robust = 0 if Y* < 0. In the other eight cases, BigAuditor = 1 if Y* ≥ 0, and BigAuditor = 0 if Y* < 0. BigAuditor_Robust is set equal to 1, if a firm is either a top-10 domestic auditor in all years or a Big 4 auditor, according to the ranking obtained based on the market share of total assets audited, and 0, otherwise. BigAuditor is set equal to 1, if a firm is either a top-10 domestic auditor in all years or a Big 4 auditor, based on the comprehensive evaluation and ranking by the CICPA, and 0, otherwise. PCIndex is a firm's political connection index constructed based on the bureaucratic ranks of corporate executives and board members who hold (or used to hold) government positions or who are (or were) a deputy to a Chinese PC or a CPPCC member, and the scores that each bureaucratic rank earns are described in Appendix. PCIndex_Robust is one of the eight alternative political connection indices constructed using various measures of political connections. Size is the natural logarithm of total assets. ROA is the return on assets. Leverage is the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. Growth is the sales growth rate. Inventory is the ratio of inventory to total assets. LargeOwn is the proportion of total shares held by the largest shareholder. ControlRights is an alternative measure used to capture the effect of ownership structures on auditor choice, which is defined as the proportion of voting rights held by the largest ultimate owner of a firm. CrossListing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if shares are cross-listed in A-share market and other markets, and 0, otherwise. Financing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if the firm raised equity capital in a given year, and 0, otherwise. Law is a variable representing the regional legal environment index. Z statistics are in parentheses. ***, ** and * represent significance at the 1, 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively.

We now test Hypothesis 2 by examining how the inverse U-shaped relationship between political connections and auditor choice hinges on the degree of severity of agency problems embedded in firms' ownership structures. To this end, following Guedhami et al. (2014), we first decompose the sample into two subsamples, based on whether or not there is separation between the largest shareholder's control and cash flow rights. The first subsample includes observations for firms with a wedge between control and cash flow rights, and the second subsample includes observations for firms with no control-ownership separation. A large wedge between the control and cash flow rights exacerbates a firm's agency problems, as it strengthens controlling shareholders' incentives to expropriate minority shareholders. We expect that the inverse U-shaped relationship is more pronounced for firms with a wedge between control and cash flow rights than for other firms. The estimated results using the two subsamples are reported in the first and second columns of Table 4, respectively. In the first subsample regression, the coefficient on PCIndex is positive and significant, and the coefficient on (PCIndex)2 is negative and significant. However, both coefficients are insignificant in the second subsample.5 The results confirm our prediction that the inverse U-shaped relationship is affected by the separation between the control and cash flow rights.

| Variables | Subsamples of firms with and without control and ownership wedge | Subsamples of firms with ControlRights ≥ 30% and ControlRights < 30% | Subsamples of firms with and without a single large shareholder | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCIndex | 4.3751*** | −0.5587 | 4.8051*** | 0.6206 | 5.5591*** | −0.8032 |

| (2.85) | (−0.23) | (2.81) | (0.32) | (3.39) | (−0.39) | |

| (PCIndex)2 | −12.8170*** | 6.3959 | −9.7406** | −2.2437 | −12.3856*** | 1.5663 |

| (−2.88) | (0.87) | (−1.96) | (−0.41) | (−2.72) | (0.25) | |

| Size | 0.2143*** | −0.2169 | 0.1571* | 0.1095 | 0.0857 | 0.2422*** |

| (3.78) | (−1.47) | (1.93) | (1.48) | (1.37) | (2.81) | |

| ROA | −1.1831 | −0.3281 | −3.1141*** | 0.6387 | 0.3669 | −3.8725*** |

| (−1.45) | (−0.19) | (−2.67) | (0.67) | (0.43) | (−3.28) | |

| Leverage | 0.1272 | −1.2855** | −0.4491 | −0.0161 | 0.2776 | −1.3282*** |

| (0.54) | (−1.98) | (−0.99) | (−0.06) | (1.21) | (−3.01) | |

| Growth | 0.0454 | −0.2961 | 0.0019 | 0.0104 | 0.0604 | −0.1512 |

| (0.40) | (−0.98) | (0.01) | (0.07) | (0.47) | (−0.85) | |

| Inventory | 0.8856** | 1.6565** | 1.0603* | 1.2265** | 0.9159** | 1.7194*** |

| (2.06) | (1.97) | (1.93) | (2.15) | (1.98) | (2.62) | |

| CrossListing | 1.2551*** | 1.0316*** | 1.4627*** | 1.2842*** | 1.1008*** | |

| (5.01) | (2.63) | (4.67) | (4.11) | (2.86) | ||

| Financing | 0.0883 | 0.0576** | 0.0217 | 0.1767 | −0.0535 | 0.1601 |

| (0.53) | (2.05) | (0.13) | (0.74) | (−0.28) | (0.83) | |

| Law | 0.1239*** | 4.8931 | 0.1325*** | 0.0935*** | 0.1191*** | 0.0929*** |

| (7.85) | (1.61) | (6.75) | (4.77) | (6.93) | (4.39) | |

| Constant | −8.1433*** | −0.5587 | −5.9242*** | −4.2494*** | −4.5048*** | −6.6839*** |

| (−6.37) | (−0.23) | (−3.40) | (−2.68) | (−3.32) | (−3.65) | |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0984 | 0.0799 | 0.0737 | 0.1014 | 0.0845 | 0.0889 |

| Chi square | 230.38*** | 69.68*** | 130.08*** | 148.55*** | 163.42*** | 122.29*** |

| Observations | 2684 | 832 | 1758 | 1766 | 2093 | 1521 |

- This table reports the estimation results for Regression 4 in various subsamples. First, the sample is decomposed into two subsamples, based on whether or not there is separation between the largest shareholder's control and cash flow rights. Second, the sample is divided into two subsamples by control concentration. The first subsample includes observations for firms with voting rights held by the largest ultimate shareholder that exceed (including) 30 percent, and the second subsample includes observations for firms with voting rights held by the largest shareholder that are less than 30 percent. Third, the sample is divided into two subsamples, based on whether or not there is a single large shareholder. The explained variable Y* is a latent variable. BigAuditor = 1 if Y* ≥ 0, and BigAuditor = 0 if Y* < 0. BigAuditor is set equal to 1, if a firm is either a top-10 domestic auditor in all years or a Big 4 auditor, based on the comprehensive evaluation and ranking by the CICPA, and 0, otherwise. PCIndex is a firm's political connection index constructed based on the bureaucratic ranks of corporate executives and board members who hold (or used to hold) government positions or who are (or were) a deputy to a Chinese PC or a CPPCC member. Size is the natural logarithm of total assets. ROA is the return on assets. Leverage is the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. Growth is the sales growth rate. Inventory is the ratio of inventory to total assets. CrossListing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if shares are cross-listed in A-share market and other markets, and 0, otherwise. Financing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if the firm raised equity capital in a given year, and 0, otherwise. Law is a variable representing the regional legal environment index. Z statistics are in parentheses. ***, ** and * represent significance at the 1, 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively.

We then, following Fan and Wong (2005), divide the sample into two subsamples by control concentration. The first subsample includes observations for firms with voting rights held by the largest ultimate shareholder that exceed (including) 30 percent, and the second subsample includes observations for firms with voting rights held by the largest shareholder that are less than 30 percent. As pointed out by Fan and Wong (2005), if corporate control rights are more concentrated, the large shareholder entrenchment is expected to be more prevalent. Thus, we expect that the inverse U-shaped relationship between political connections and auditor choice is more pronounced in the high-control group. The estimated results of the two subsamples are reported in the third and fourth columns of Table 4, which are also in line with our prediction.

To provide further evidence, we finally divide the sample into two subsamples, based on whether or not there is a single large shareholder. There is a single large shareholder in a firm, if the proportion of total shares held by the second largest shareholder is less than 10 percent. In the presence of multiple large shareholders, the agency conflicts between corporate insiders and outside investors are less severe. This is because these large shareholders have the power and incentives to actively cross-monitor each other, preventing insiders from expropriating minority shareholders (Pagano and Roell, 1998). It follows that the inverse U-shaped relationship between political connections and auditor choice is more pronounced for firms with a single large shareholder. The estimated results of the two subsamples are reported in the fifth and sixth columns of Table 4, which are also consistent with our prediction. Collectively, the preceding results support Hypothesis 2 that the inverse U-shaped relationship is stronger for firms with ownership structures that intensify agency conflicts between corporate investors and outside investors.

5.2 Political connections and accounting transparency

Accounting transparency is positively associated with auditor quality. Thus, we expect that political connections and accounting transparency have a relationship similar to the relationship between political connections and auditor choice documented in Section 5.1. To test Hypothesis 3, we run Regression 5 using the full sample. The estimation results of Regression 5 if accounting transparency is measured by EA are reported in the first column of Table 5. We note that the coefficient on the variable PCIndex is negative and significant, while the coefficient on (PCIndex)2 is positive and significant, indicating that accounting transparency measured by earnings aggressiveness increases with the degree of political connectedness for firms with less strong political connections, but decreases with the degree of political connectedness for firms with particularly strong political connections. These results lend support to the prediction in Hypothesis 3 that the relationship between political connections and accounting transparency exhibits an inverse U-shaped pattern.

| Independent variables | Explained variable: EA | Explained variable: ES | Explained variable: EAES |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCIndex | −0.0988* | 1.3033* | 2.0335** |

| (−1.89) | (1.68) | (1.99) | |

| (PCIndex)2 | 0.2496* | −4.1773* | −6.3920** |

| (1.65) | (−1.75) | (−2.24) | |

| BigAuditor | −0.0054 | −0.0366 | 0.0378 |

| (−1.13) | (−0.43) | (0.37) | |

| Size | −0.0118*** | 0.0072 | −0.0149 |

| (−4.51) | (0.26) | (−0.36) | |

| ROA | 0.0781* | −0.8417* | |

| (1.87) | (−1.71) | ||

| Leverage | 0.1033*** | 0.1815** | −0.5218*** |

| (9.10) | (2.27) | (−3.88) | |

| Growth | 0.0368*** | −0.0978* | −0.2360*** |

| (5.14) | (−1.70) | (−3.11) | |

| LargeOwn | 0.0632*** | −0.0959 | 0.0621 |

| (3.97) | (−0.46) | (0.20) | |

| CrossListing | 0.0039 | −0.0164 | 0.2065 |

| (0.34) | (−0.32) | (0.97) | |

| Financing | 0.0698*** | −0.0039 | −0.5726*** |

| (9.79) | (−0.04) | (−4.39) | |

| Law | −0.0016*** | 0.0046 | 0.0347*** |

| (−2.81) | (0.67) | (3.18) | |

| Constant | 0.3249*** | −0.5129 | 4.4719*** |

| (5.93) | (−0.87) | (5.09) | |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | / | Control |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.1506 | 0.0264 | 0.0678 |

| F statistics | 11.5021*** | 1.7511** | 8.2846*** |

| Observations | 3637 | 411 | 2790 |

- This table reports the estimation results for Regression 5, in which the explained variable is accounting transparency, measured by earnings aggressiveness (EA), earnings smoothing (ES), or an aggregate measure EAES. PCIndex is a firm's political connection index constructed based on the bureaucratic ranks of corporate executives and board members who hold (or used to hold) government positions or who are (or were) a deputy to a Chinese PC or a CPPCC member. BigAuditor is set equal to 1, if a firm is either a top-10 domestic auditor in all years or a Big 4 auditor, based on the comprehensive evaluation and ranking by the CICPA, and 0, otherwise. Size is the natural logarithm of total assets. ROA is the return on assets. Leverage is the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. Growth is the sales growth rate. Inventory is the ratio of inventory to total assets. LargeOwn is the proportion of total shares held by the largest shareholder. CrossListing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if shares are cross-listed in A-share market and other markets, and 0, otherwise. Financing is a dummy variable, which takes the value of 1 if the firm raised equity capital in a given year, and 0, otherwise. Law is a variable representing the regional legal environment index. t-statistics are in parentheses. ***, ** and * represent significance at the 1, 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively.

Focusing on the control variables, we find that the coefficients on the variables Size and Law are significantly negative, indicating that both variables are positively associated with accounting transparency. Meanwhile, the coefficients on ROA, Leverage and Growth are significantly positive. This suggests that firms with better performance, higher leverage ratio or higher growth rate tend to have lower accounting transparency, which is in line with the previous findings that these firms are less likely to hire high-quality auditors (Ghoul et al., 2007; Wang and Xin, 2011; Srinidhi et al., 2012; Guedhami et al., 2014). In addition, firms with a single large shareholder exhibit lower accounting transparency than do other firms, which is expected given our previous finding that these firms are more eager to engage low-quality auditors. Finally, we find that firms with new equity issues in a particular year exhibit lower accounting transparency, as they have stronger incentives to engage in earnings management.

The estimation results of Regression 5 in the cases where the explained variable is ES or EAES are also reported in Table 5. The sign and significance of the estimated coefficients on PCIndex and (PCIndex)2 further show that our conclusions regarding the relationship between political connections and accounting transparency still hold qualitatively even if these alternative measures for accounting transparency are used in the regression. In addition, the effects of the control variables are generally consistent with those in the case where EA is the explained variable, except for the result that firms' leverage is now positively associated with ES. However, the effect of leverage on ES is in line with the finding by Chih et al. (2008).

6 Conclusions

Political connections intensify agency conflicts between corporate insiders and outside investors, which explains why political connections are related to firms' auditor choice as well as accounting transparency. For insiders in connected firms, there are both benefits and costs of hiring high-quality auditors. Connected firms may benefit from high-quality audits, as the stricter monitoring imposed by high-quality auditors helps lower information asymmetry and thus increases valuations. However, the stricter monitoring imposed by high-quality auditors constraints corporate insiders from extracting political benefits. As a result, connected firms may be more or less likely to hire a high-quality auditor than non-connected firms, depending on whether the benefits outweigh the costs.

Using the data on Chinese private sector firms, we document that the way in which political connections impact auditor choice hinges on the degree of political connectedness. To capture the variation in the degree of political connectedness in Chinese private sector firms, we construct a political connection index, based on the bureaucratic ranks of corporate executives and board members in these firms. We find that for firms with less strong political connections, corporate insiders' incentives to reduce information asymmetry are particularly strong, and the likelihood of hiring high-quality auditors increases with the degree of political connectedness. However, for firms with particularly strong political connections, corporate insiders' incentives to extract political benefits become stronger, and thus, the likelihood of hiring high-quality auditors decreases with the degree of political connectedness. We find that this inverse U-shaped relationship between political connections and auditor choice is particularly pronounced for firms with ownership structures that intensify agency conflicts between corporate insiders and outside investors.

High-quality audits limit corporate insiders' discretion to distort financing reporting, thereby enhancing accounting transparency. We also find that accounting transparency, measure by EA, ES and EAES, is nonlinearly related to political connections. Accounting transparency increases with the degree of political connectedness for firms with less strong political connections, but decreases with the degree of political connectedness for firms with relatively strong political connections.

Our analysis explains why prior research reports conflicting findings about the relationship between political connections and auditor choice as well as accounting transparency. It furthers our understanding of the role that the strength of political connections plays in explaining the value of high-quality audits in politically connected firms. Future research can be conducted to examine how auditor choice in a politically connected firm impacts agency costs, and how this effect is related to the degree of such firms' political connectedness.

Notes

Appendix A

Political connection scores

| Political connection type | Bureaucratic rank | Political connection score |

|---|---|---|

| Government officials | Deputy minister and above | 7 |

| Bureau director (Ting) | 6 | |

| Deputy bureau director (Fu Ting) | 5 | |

| County/division head (Chu) | 4 | |

| Deputy county/division head (Fu Chu) | 3 | |

| Township/section head (Ke) | 2 | |

| Deputy township/section head (Fu Ke) and below | 1 | |

| Deputies to the Chinese PC and the CPPCC members | National level | 6 |

| Provincial level | 4 | |

| Local or city level | 2 |

- This table presents the political connection scores assigned to each bureaucratic rank.

| Corporate position | Mean | Standard deviation | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Members of board of directors and executive managers | 6.0632 | 6.1782 | 0 | 55 |

| Chair of board of directors | 1.1419 | 2.0020 | 0 | 8 |

| Members of board of directors | 6.5187 | 6.9933 | 0 | 55 |

| Chief executive officer | 0.5319 | 1.3754 | 0 | 8 |

| Executive managers | 1.0691 | 2.0534 | 0 | 17 |

- This table presents the descriptive statistics of political connection scores of corporate executives and board members by positions.

| Observations | Mean | Standard deviation | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | 3640 | 6.0632 | 6.1781 | 0 | 55 |

| 2004 | 247 | 6.8057 | 6.9014 | 0 | 41 |

| 2005 | 264 | 6.6553 | 6.8614 | 0 | 55 |

| 2006 | 313 | 6.3578 | 6.0796 | 0 | 37 |

| 2007 | 380 | 6.2763 | 6.0162 | 0 | 37 |

| 2008 | 438 | 6.2557 | 6.6359 | 0 | 52 |

| 2009 | 487 | 5.9548 | 6.1237 | 0 | 48 |

| 2010 | 494 | 5.9474 | 6.1289 | 0 | 41 |

| 2011 | 509 | 5.6798 | 5.7330 | 0 | 41 |

| 2012 | 508 | 5.4882 | 5.6737 | 0 | 38 |

- This table reports the descriptive statistics of political connection scores for firms in the sample period as well as in each year.