Shareholder say on pay and CEO compensation: three strikes and the board is out

Abstract

From 2011 in Australia, if over 25% of shareholders vote against a non-binding remuneration resolution, firms are awarded a ‘strike’. We examine 237 firms that receive a strike relative to matched firms, and find no association with any measure of CEO pay. However, we do find that strike firms have higher book-to-market and leverage ratios, suggesting that the remuneration vote is not used to target excessive pay. We also find that firms respond to a strike by decreasing the discretionary bonus component of CEO pay by 57.10% more than non-strike firms and increasing their remuneration disclosure by 10.95%.

1 Introduction

In response to popular criticism over excessive Chief Executive Officer (CEO) remuneration, many countries have introduced mandatory shareholder ‘say on pay’ resolutions at annual general meetings (AGM). Say on pay provides an opportunity for principals (shareholders) to voice their opinion over how the delegated principals (the board of directors) have been remunerating agents (senior executives and management). Concerns have been raised that say on pay may be an ineffective governance mechanism as shareholders may lack remuneration expertise, and resolutions are non-binding (Kaplan, 2007). We examine both of these concerns by investigating the determinants of shareholder say on pay voting results, and its effect on future CEO remuneration and remuneration disclosure.

Prior literature has studied the link between shareholder say on pay and the pay-for-performance link in Australia (Clarkson et al., 2011; Monem and Ng, 2013). We extend the Australian say on pay literature by investigating both the level of CEO remuneration and excess remuneration, and changes in CEO pay and remuneration disclosure. The Australian setting is unique, as it has attempted to empower minority shareholders by only requiring a 25 percent vote against the remuneration report to trigger a ‘strike’ against the firm, preventing directors or managers from voting on say on pay resolutions and forcing the directors to face re-election if the firm obtains two initial ‘strikes’ and a third ‘spill vote’ strike. Australia's two-strikes rule appears targeted at the possibility of ‘board capture’, whereby boards are incapable of effectively monitoring the executives (Hermalin and Weisbach, 1998; Core et al., 1999).

This study examines 274 Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) firms that receive strikes in 2011 or 2012 relative to non-strike size- and industry-matched firms. We find that no measure of reported or excess (residual) CEO pay is associated with receiving a strike or higher dissent against the remuneration resolution. Instead, we find that the book-to-market (BTM) and leverage ratios are associated with whether a firm receives a strike. This may suggest that the remuneration vote is used against boards with a lower firm valuation. However, strike firms have a 57.10 percent larger decrease in the CEO's bonus than non-strike firms, suggesting that a strike can rein in pay. Receiving a strike and higher dissent against the remuneration resolution is also associated with an increase in length of the remuneration report by an average of 10.95 percent, or 0.77 pages in the following year. Thus, we contribute to corporate governance research by reporting evidence that suggests say on pay voting may be ineffective, as shareholder dissent is not associated with excess remuneration.

The study is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the regulatory background and develops the hypotheses, Section 3 outlines the research method, and Section 4 discusses the results. Last, conclusions are presented in Section 5.

2 Background and hypothesis development

2.1 Regulation around executive remuneration in Australia

Since 2005, Australian firms’ remuneration reports contain salary components for the board of directors and key management personnel (KMP). For each individual, the following components of remuneration are often reported: base salary, cash bonus (short term incentives), non-monetary benefits, superannuation benefits, termination benefits, equity-based payments and total remuneration. Shareholders can vote on the overall remuneration report through mandatory, nonbinding, AGM say on pay resolutions that were first introduced in the Corporations Act of Australia in 2004. After concerns were raised that firms were ignoring the shareholders’ votes (Clarkson et al., 2006), the two-strikes rule was passed as an amendment, taking effect on 1 July 2011. The main change was if 25 percent or more of eligible votes are against the remuneration report a firm receives a ‘strike’. If the firm receives a strike at two consecutive AGMs, there must be a majority-based vote on whether the whole board should be put up for re-election within 90 days of the AGM (a ‘spill vote’). If a majority of eligible votes support director re-election (the ‘third strike’), that re-election (at a ‘spill meeting’) will occur under normal voting circumstances, that is a majority vote by all voting shareholders.

Both Australasian finance (Benson et al., 2014) and accounting (Benson et al., 2015) literature have previously considered corporate governance and CEO remuneration issues and made notable contributions to the academic literature. We note a few innovations in the two-strikes rule in Australia. First, although the resolution is non-binding in regard to remuneration contracts, it has a direct consequence on directors, with two strikes leading to a board of directors spill vote. Consistent with excessive CEO power as a key motivation for say on pay initiatives (Mangen and Magnan, 2012), the spill vote targets non-executive directors who may not be effectively monitoring remuneration, or representing shareholder interests. Second, prior literature has found a low dissenting vote for remuneration resolutions, especially for firms with high ownership concentration (Conyon and Sadler, 2010). Thus, the low cut-off of 25 percent for a strike would likely result in more strikes than in settings requiring a majority vote. This low cut-off is targeted at assisting minority shareholders who could not form a majority voting bloc and makes a strike an easier way to express shareholder dissent than electing an independent director on a related platform. Third, the legislation also excludes parties included in the remuneration report from voting on the remuneration report (or controlling proxy votes).1 Although prior literature has found a negative association between insider ownership and shareholder dissent (Conyon and Sadler, 2010; Ertimur et al., 2011), this rule has the effect of removing a deflating effect on the percentage of shareholder dissent, equal to the proportion of shares eligible to vote over total shares and making it easier for insider dominated boards to receive a strike.

2.2 Hypothesis development

Cai and Walkling (2011) outline three possible outcomes for shareholders from say on pay initiatives: positive (the ‘alignment’ hypothesis), negative (the ‘interference’ hypothesis) or insignificant (the ‘neutral’ hypothesis). However, there is mixed evidence on shareholder motivations for targeting firms with dissenting votes on remuneration resolutions. If dissenting votes are cast to communicate dissatisfaction with remuneration, firms with higher remuneration packages should have greater dissent in remuneration resolutions. However, in the context of criticising remuneration, Ertimur et al. (2011) stress the distinction between high total pay and high excess pay.2 Differences in normal pay reflect rational remuneration in exchange for differences in the demands on CEOs for managing certain firm types. On the other hand, situations of ‘board capture’, where board oversight of CEO remuneration is significantly influenced by the CEO, are associated with excess pay beyond that which would be normal for the firms characteristics (Hermalin and Weisbach, 1998; Core et al., 1999).

One of the criticisms raised against say on pay voting is the possibility that shareholders may not have the expertise or sophistication necessary to identify excess pay (Deane, 2007). If shareholders cannot isolate excess pay, they may unwittingly target firm types with high normal pay for protest. However, Carter and Zamora (2009) and Conyon and Sadler (2010) both report UK evidence of shareholder dissent being associated with excess pay. In the USA, Ertimur et al. (2011) find that while activist groups target firms with high total pay for sponsored remuneration resolutions, there is greater overall dissent for firms with high excess pay. Thus, there is some evidence suggesting that shareholders can effectively identify excessive remuneration.

Deane (2007) raises the concern that some shareholders may consider measures of management performance other than stock returns when analysing pay for performance. Ertimur et al. (2011) find that while activist shareholders consider social performance when targeting firms for voluntary remuneration resolutions, the voting behaviour of most shareholders suggests they are only concerned with stock performance. Poor performing firms have been found to be more likely to be subject to a vote-no campaign (Gillan and Starks, 2000; Del Guercio et al., 2008), suggesting that factors indirectly associated with remuneration may be associated with shareholder dissent.

- H1a There is a positive association between receiving a strike and reported pay

- H1b There is a positive association between receiving a strike and excess pay

If shareholder dissent expressed in management remuneration resolutions is determined by unsatisfactory remuneration practice, then significant shareholder dissent could affect future remuneration (Carter and Zamora, 2009; Conyon and Sadler, 2010; Ferri and Maber, 2013). In the USA, a reduction in total pay and a change in compensation structure follow high levels of shareholder and proxy advisor dissent (Ertimur et al., 2011, 2013). Ferri and Maber (2013) find that 23 of 75 UK firms they categorise as having received high dissent have changes in their remuneration structure in the following year, but found no change in total CEO pay. Carter and Zamora (2009) report a decrease in excess remuneration following dissent, but Conyon and Sadler (2010) document no significant changes to excess remuneration or remuneration structure. In Australia, Clarkson et al. (2011) report an increase in the pay-for-performance link following the introduction of the original say on pay scheme, although there was also a positive trend in pay for performance prior to the introduction of that scheme. Monem and Ng (2013) find no pay-for-performance link for strike and matched firms in 2011, but do in 2012.

One possible explanation for not expecting a change in management remuneration in the year immediately following shareholder dissent, is that remuneration may be contracted across multiple years (Brown et al., 2011). However, as some contracts will expire in any given year, there is some opportunity for a change of remuneration in response to shareholder dissent on average. Therefore, we empirically test the effectiveness of the ‘strikes’ regulation, by investigating whether shareholder dissent can pressure the board of directors to realign the remuneration of management with the interests of shareholders. We state our second hypothesis as:

- H2 There is a negative association between the change in reported pay and receiving a strike

- H3 There is a positive association between the change in remuneration disclosure and receiving a strike

3 Research method

3.1 Sample

We collect all 248 instances of a company listed on the ASX receiving a ‘strike’ in 2011 or 2012 based on the Remuneration Report Database provided by Fairfax Business Research. Observations are removed from the sample if they do not have an available annual report, leaving 237 ‘strike’ firm-years. We then create a control sample of firms matched on industry and size. Within the strike firm's 4 digit GICS industry, the firm with the smallest absolute difference in market capitalisation as at the annual report balance date of the strike firm is selected as the matched firm. Each matched firm is unique, that is a matched firm cannot be matched against two ‘strike’ firms. Matched firms are also replaced if they do not have an available annual report or are not domiciled in Australia.3 Our matching approach is consistent with other say on pay studies (e.g. Ertimur et al., 2011). One advantage of our approach is that it reduces the bias created by estimating a pay model from a sample that is fundamentally different to the subsample which that model will be applied to. The corresponding disadvantage is that the pay model estimated from a matched sample may be fundamentally different to the pay models estimated in prior literature from the broader market sample.

Remuneration and governance data are hand collected from annual reports and voting results from notices of AGM results. Other firm data are collected from SIRCA, Aspect Huntley and Datastream. Thus, a full sample of 474 firm-year observations is available for the 2 years.

3.2 Determinants of strikes research models

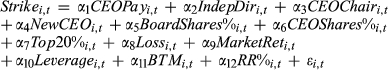

(1)

(1)All variables are as defined in Table 1. Variables are measured in year t, the year of the strike, and are collected from the annual report the shareholders are voting on. All market variables are measured as per the annual report balance date in the year of the strike. We also remodel Equation 1 as an ordinary least squares (OLS) and replace Strikei,t with Dissenti,t as the dependent variable.4

| Dependent variables | |

| Strike i,t | A binary variable equal to one if firm i received a strike in year t |

| Dissent i,t | The percentage of votes against the remuneration resolution of firm i in year t |

| CEOPay variables | |

| LnCEOSalary i,t | Natural logarithm of the reported base CEO/MD cash salary of firm i in year t |

| LnCEOBonus i,t | Natural logarithm of the reported cash bonus for the CEO/MD of firm i in year t |

| LnCEOEquity i,t | Natural logarithm of the reported value of equity and options for the CEO/MD of firm i in year t |

| LnCEOTotal i,t | Natural logarithm of the total remuneration reported for the CEO/MD of firm i in year t |

| Control variables | |

| IndepDir i,t | The proportion of independent directors for firm i in year t |

| CEOChair i,t | A binary variable equal to one if the CEO of firm i is also the chairman in year t |

| NewCEO i,t | A binary variable equal to one if the CEO of firm i was in their first year in year t |

| BoardShares%i,t | The percentage of shares owned by the board of firm i in year t |

| CEOShares%i,t | The percentage of shares owned by the CEO of firm i in year t |

| Top20%i,t | The percentage of shares owned by the largest 20 shareholders of firm i in year t |

| Loss i,t | A binary variable equal to one if net profit after tax is negative for firm i in year t |

| MarketRet i,t | The 1-year log buy and hold return for firm i less the 1-year log buy and hold return for the ASX All-Ordinaries index from the annual report balance date in year t |

| Leverage i,t | Total liabilities divided by total equity of firm i in year t |

| BTM i,t | The book value of equity divided by market capitalisation of firm i as at the annual report balance date in year t |

| RR%i,t | The page length of the remuneration report in the annual report divided by the page length of the annual report of firm i, in year t |

| Additional variables (for Equations 2, 4 or 5) | |

| RRLength i,t | The page length of the remuneration report in the annual report of firm i in year t |

| LnMCap i,t | The market capitalisation as at the annual report balance date of firm i in year t |

| KMP i,t | The number of individuals specified in the remuneration report of firm i in year t |

We examine the level of CEO salary, bonuses, equity grants and total remuneration.5 Although examining the pay-for-performance link provides useful insights, a CEO can also be overpaid or underpaid relative to other CEOs depending on their realised total pay, thus we focus on pay levels.

First, we control for corporate governance factors. Larger boards are argued to be less effective monitors (Yermack, 1996). Independent directors and remuneration committees may monitor remuneration (Fama and Jensen, 1983) or be ‘captured’ and become ineffective monitors (Hermalin and Weisbach, 1998; Core et al., 1999).

Second, we control for CEO characteristics which may affect remuneration (Bebchuck and Fried, 2003). The first year of the CEO's tenure may be atypical due to incentives only being realised after performance. We also control for the amount of shares owned by the CEO and board as these are mentioned in the say on pay regulation. In addition, blockholders could also provide external monitoring of remuneration (Hartzell and Starks, 2003). Craighead et al. (2004) find that firms with widely held share ownership tend to have weaker pay for performance. Thus, ownership structure may proxy for the demand by uninformed shareholders for remuneration disclosure to properly assess management remuneration.

Third, we control for the economic characteristics of the firm. Larger, more complex firms with greater investment opportunities and risk are likely to pay more, with firm size and complexity measured through sales, book-to-market ratio or the debt-to-equity ratio (Murphy, 1985; Core et al., 1999). We also control for both market and accounting measures of firm performance that particularly relate to the bonus component of remuneration (Murphy, 1985; Core et al., 1999; Matolcsy and Wright, 2011). Gillan and Starks (2000) and Del Guercio et al. (2008) report a negative association between performance and shareholder dissent, interpreting this as a reflection of shareholders’ economic interest.

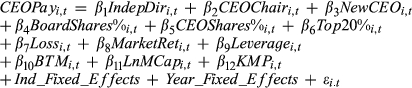

Shareholders may also be reacting to excess rather than absolute pay (H1b). To test this possibility, we follow Core et al. (1999, 2008) and test whether residual and predicted values of CEO payi,t are associated with shareholder dissent, where these variables are specified as CEOResiduali,t and CEOPredictedi,t. First, we estimate the determinants of CEO pay using the below regression and calculate CEOPredictedi,t. CEOResdiuali,t is then calculated as the difference between the reported and predicted CEO pay. We then test whether CEOPredictedi,t or CEOResdiuali,t are associated with receiving a strike. This 2SLS regression approach may also alleviate concerns around endogeneity, as CEO compensation and receiving a strike may be jointly determined by unknown, omitted factors.

(2)

(2) (3)

(3)LnMCapi,t is omitted from Equations 1 and 3 as the strike and non-strike subsamples have been matched on this variable.

3.3 Consequences of strikes empirical models

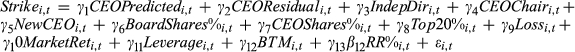

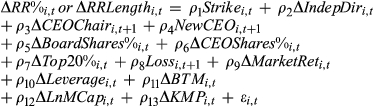

(4)

(4) (5)

(5)4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 2 Panel A presents descriptive statistics for firms that received a strike. The mean cash salary for CEOs is $433,401 (median = $335,000), with a range from $0 to $2,984,801. This range reflects the diversity in the size of firms that received a strike, with market capitalisation of less than $1 m to $6,772.5 m. The dissenting votes that led to receiving a strike range from 25.0 to 99.9 percent. Subsequent to the strike, most mean and median CEO pay categories decreased. The descriptive statistics also show that some strike firms are very tightly controlled. As strike firms can be very small and are often loss making (69.6 percent, Panel B) potentially leading to negative equity, the market return, leverage and BTM measures can be distorted. Thus, the top and bottom 2.5 percent of these variables are winsorised.

| Panel A: Strike firm continuous variable descriptive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

| CEOSalary t | 433,401 | 335,000 | 394,819 | 0 | 2,984,801 |

| CEOBonus t | 94,503 | 0 | 278,913 | 0 | 2,400,000 |

| CEOEquity t | 173,229 | 0 | 534,324 | −207,653 | 4,110,275 |

| CEOTotal t | 779,934 | 474,306 | 1,045,328 | 0 | 7,710,275 |

| Dissent t | 0.461 | 0.41 | 0.179 | 0.25 | 0.999 |

| KMP t | 8.249 | 8 | 3.272 | 3 | 19 |

| IndepDir t | 0.567 | 0.6 | 0.249 | 0 | 1 |

| BoardShares%t | 0.1 | 0.029 | 0.149 | 0 | 0.736 |

| CEOShares%t | 0.056 | 0.007 | 0.114 | 0 | 0.797 |

| Top20%t | 62.7 | 63.6 | 18.1 | 10 | 95 |

| MarketRet t | −0.259 | −0.26 | 0.546 | −1 | 1 |

| Leverage t | 0.304 | 0.249 | 0.254 | 0.015 | 0.931 |

| BTM t | 1.237 | 0.923 | 0.992 | 0.075 | 3.754 |

| MCapt ($m) | 221 | 21.5 | 675.8 | 0.7 | 6,772.50 |

| LnMCap t | 17.303 | 16.881 | 1.929 | 13.525 | 22.636 |

| RRLength t | 7.059 | 6 | 4.675 | 1 | 33 |

| RR%t | 0.081 | 0.073 | 0.034 | 0.011 | 0.223 |

| CEOSalary t+1 | 442,484 | 333,945 | 407,681 | 0 | 2,984,225 |

| CEOBonus t+1 | 92,729 | 0 | 252,943 | 0 | 1,806,000 |

| CEOEquity t+1 | 156,145 | 2,351 | 448,652 | −53,692 | 3,075,000 |

| CEOTotal t+1 | 722,791 | 425,441 | 1,005,070 | 0 | 7,891,719 |

| RRLength t+1 | 8.023 | 6 | 5.277 | 1 | 34 |

| RR%t+1 | 0.090 | 0.083 | 0.037 | 0.020 | 0.276 |

| Panel B: Binary variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Strike | Matched | ||||||

| Yes | Percent | No | Percent | Yes | Percent | No | Percent | |

| CEOChair | 40 | 16.88 | 197 | 83.12 | 37 | 15.61 | 200 | 84.39 |

| NewCEO | 44 | 18.57 | 193 | 81.43 | 32 | 13.50 | 205 | 86.50 |

| Loss | 165 | 69.62 | 72 | 30.38 | 153 | 64.56 | 84 | 35.44 |

| Panel C: Univariate differences (strike – matched) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean diff. | t-stat | z-score |

| LnCEOSalary | 0.191 | 1.007 | 3.293*** |

| LnCEOBonus | 0.274 | 0.544 | 0.540 |

| LnCEOEquity | 0.175 | 0.045 | 0.172 |

| LnCEOTotal | 0.197 | 1.203 | 2.389* |

| Dissent | 0.417 | 34.164*** | 18.684*** |

| KMP | 0.502 | 1.735 | 1.460 |

| IndepDir | 0.042 | 1.846 | 2.121* |

| BoardShares% | −0.002 | −0.135 | 0.151 |

| CEOShares% | −0.015 | −1.233 | 1.160 |

| Top20% | −1.936 | −1.178 | 1.046 |

| MarketRet | −0.101 | −2.011* | 2.382* |

| Leverage | 0.037 | 1.666 | 1.334 |

| BTM | 0.176 | 2.046* | 1.941 |

| LnMCap | 0.013 | 0.076 | 0.059 |

| RRLength | 0.846 | 2.174* | 1.645 |

| RR% | 0.004 | 1.415 | 0.871 |

| Change variables | |||

| ΔLnCEOSalary | −0.249 | −0.877 | 2.488* |

| ΔLnCEOBonus | −1.093 | −2.338* | 1.822 |

| ΔLnCEOEquity | 0.128 | 0.242 | 0.093 |

| ΔLnCEOTotal | −0.378 | −1.322 | 1.722 |

| ΔRRLength | 0.403 | 1.310 | 1.959* |

| ΔRR% | 0.003 | 1.126 | 2.261* |

- This table Panel A presents descriptive statistics for strike firms. Panel B presents the count and percentage for binary variables for both strike and non-strike firms. Panel C reports univariate tests using the student t-test and the Mann–Whitney-U test. Two-tailed test of significance: ***< 0.001, **< 0.01 and *< 0.05.

Panel C reports the results of univariate tests on the statistical differences between strike and matched firm characteristics. The mean pay for firms that received a strike does not appear to be statistically higher than matched firms in any of the reported pay categories. Using non-parametric tests, CEO cash salary and total pay are significantly higher for strike firms. We also find some evidence suggesting that strike firms had a smaller change in CEO pay than non-strike firms, in terms of cash salary and bonus components.

The length of the annual report dedicated to the remuneration report (RRLength) is also larger for strike firms than non-strike firms in parametric tests, but not in non-parametric tests. Neither test reported a significant difference in the proportion of the annual report dedicated to the remuneration report (RR%) between strike and non-strike firms. Panel A shows that strike firms devote on average 7.059 pages to the remuneration report in the year of a strike and increase disclosure to 8.023 pages in the year following a strike, which represents 8.1 and 9.0 percent of the total length of the annual reports, respectively. Non-parametric tests find that both the length (ΔRRLength) of the remuneration report, and the proportion of the annual report dedicated to the remuneration report (ΔRR%) increase more for strike firms than non-strike firms in the year following a strike.

The only control variable with a significant coefficient consistent across parametric and non-parametric tests is market return, in that strike firms have a lower market return. This suggests that shareholders may use the remuneration resolution to express disapproval at poor firm performance.

4.2 CEO pay and receiving a strike

Table 3 shows that no specification of CEO pay (salary, bonus, equity or total) is significantly associated with receiving a strike (Panel A) or with a higher dissent vote (Panel B). We find that firms with more independent directors, higher leverage and a higher BTM ratio are more likely to receive a strike. This association is reinforced by a significant positive coefficient for Leverage and BTM with Dissent in Panel B; however, the coefficient for the proportion of independent directors is not significant. As there is a consistent significant association with the BTM ratio, but not the market return over the past year (MarketRet) or whether the firm made a loss in the current year (Loss),7 we interpret this result as suggesting shareholders could be voting against several years’ of poor performance rather than just bad performance in the current year. In addition to several years of poor performance, a combination of high leverage and a high BTM may also indicate a firm in financial distress, with shareholders voting against boards who have led the firm into a poor financial state. However, the BTM ratio is a noisy valuation multiple, and we cannot distinguish between the interpretation that the BTM ratio causes dissent or that BTM and dissent are jointly (and possibly independently) caused by other factors. Furthermore, other proxies for market performance, accounting performance, ownership structure and corporate governance are all insignificant.8 A valuation or risk rationale is also consistent with the positive coefficient on Leverage, as higher leverage could reflect several recent years of losses eroding net assets. Both board and CEO shareholding are not associated with receiving a strike, consistent with the exclusion of directors and management from voting on their remuneration. In addition, remuneration report disclosure (RR%) is not significantly associated with receiving a strike, suggesting that firms that have similar remuneration, but spend more time explaining the basis of remuneration are not spared from a strike. Overall, our results support prior literature that finds worse performing firms are more likely to be the subject of a vote-no campaign (Gillan and Starks, 2000; Del Guercio et al., 2008).

| Panel A: Strike | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coeff. | p-Value | Coeff. | p-Value | Coeff. | p-Value | Coeff. | p-Value |

| LnCEOSalary | 0.047 | 0.347 | ||||||

| LnCEOBonus | 0.018 | 0.381 | ||||||

| LnCEOEquity | −0.007 | 0.703 | ||||||

| LnCEOTotal | 0.071 | 0.236 | ||||||

| IndepDir | 0.959 | 0.019* | 0.905 | 0.026* | 0.937 | 0.021* | 0.950 | 0.020* |

| CEOChair | 0.302 | 0.277 | 0.307 | 0.272 | 0.272 | 0.326 | 0.294 | 0.289 |

| NewCEO | 0.318 | 0.235 | 0.365 | 0.181 | 0.324 | 0.226 | 0.321 | 0.230 |

| BoardShares% | 0.329 | 0.631 | 0.317 | 0.642 | 0.253 | 0.711 | 0.333 | 0.626 |

| CEOShares% | −0.376 | 0.640 | −0.438 | 0.581 | −0.595 | 0.455 | −0.339 | 0.673 |

| Top20% | −0.010 | 0.115 | −0.010 | 0.118 | −0.009 | 0.133 | −0.010 | 0.100 |

| Loss | 0.289 | 0.216 | 0.310 | 0.195 | 0.249 | 0.279 | 0.297 | 0.203 |

| MarketRet | −0.165 | 0.395 | −0.166 | 0.392 | −0.145 | 0.458 | −0.167 | 0.389 |

| Leverage | 0.937 | 0.029* | 0.933 | 0.030* | 0.960 | 0.025* | 0.951 | 0.027* |

| BTM | 0.256 | 0.022* | 0.269 | 0.016* | 0.260 | 0.020* | 0.260 | 0.020* |

| RR% | 4.309 | 0.184 | 4.064 | 0.219 | 5.063 | 0.133 | 3.910 | 0.234 |

| Constant | −1.713 | 0.037* | −1.191 | 0.035* | −1.138 | 0.044* | −2.002 | 0.029* |

| Chi-square | 26.481 | 0.009** | 26.344 | 0.01** | 25.72 | 0.012* | 27.058 | 0.008** |

| Nagelkerke R 2 | 7.2% | 7.2% | 7.0% | 7.6% | ||||

| Classification % | 60.8% | 59.3% | 59.7% | 59.9% | ||||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | ||||

| Panel B: Dissent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat |

| LnCEOSalary | 0.009 | 1.480 | ||||||

| LnCEOBonus | 0.003 | 1.371 | ||||||

| LnCEOEquity | −0.001 | −0.635 | ||||||

| LnCEOTotal | 0.011 | 1.565 | ||||||

| IndepDir | 0.087 | 1.834 | 0.077 | 1.622 | 0.083 | 1.760 | 0.084 | 1.784 |

| CEOChair | 0.026 | 0.815 | 0.027 | 0.840 | 0.021 | 0.653 | 0.024 | 0.755 |

| NewCEO | 0.002 | 0.072 | 0.011 | 0.343 | 0.004 | 0.115 | 0.003 | 0.090 |

| BoardShares% | 0.100 | 1.250 | 0.098 | 1.224 | 0.086 | 1.070 | 0.099 | 1.247 |

| CEOShares% | 0.053 | 0.570 | 0.042 | 0.459 | 0.013 | 0.135 | 0.053 | 0.572 |

| Top20% | −0.001 | −1.823 | −0.001 | −1.794 | −0.001 | −1.700 | −0.001 | −1.893 |

| Loss | 0.052 | 1.904 | 0.056 | 2.002* | 0.045 | 1.662 | 0.052 | 1.908 |

| MarketRet | −0.022 | −0.956 | −0.022 | −0.949 | −0.018 | −0.779 | −0.022 | −0.954 |

| Leverage | 0.135 | 2.726** | 0.135 | 2.709** | 0.140 | 2.819** | 0.138 | 2.788** |

| BTM | 0.052 | 4.070*** | 0.054 | 4.272*** | 0.053 | 4.134*** | 0.053 | 4.146*** |

| RR% | 0.034 | 0.091 | −0.009 | −0.023 | 0.178 | 0.458 | −0.012 | −0.032 |

| Constant | 0.025 | 0.262 | 0.120 | 1.829 | 0.130 | 1.979* | −0.001 | −0.01 |

| F-stat | 3.218*** | 3.19*** | 3.057*** | 3.241*** | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 5.3% | 5.3% | 5.0% | 5.4% | ||||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | ||||

- This table presents logit regressions on receiving a strike (Panel A) and OLS regressions on dissent (Panel B) and CEO pay. Two-tailed test of significance: ***< 0.001, **< 0.01 and *< 0.05.

Next, we regress CEO pay on firm characteristics and use this to calculate predicted and residual (excess) CEO pay (Table 4). Table 5 then examines whether excess pay is associated with receiving a strike. Again we find that no measure of CEO pay (both predicted and residual salary, bonus, equity and total pay) is significantly associated with receiving a strike or the vote against the remuneration resolution (Dissent). The BTM ratio is consistently significantly associated with receiving a strike and dissent. As the association between the BTM ratio and Strike/Dissent is still present after we include CEO residual pay, the evidence suggests that shareholders are more concerned about sustained poor performance than excess pay. We also find some evidence that Leverage effects shareholder dissent. The positive relationship between independent directors and receiving a strike could suggest that shareholders are further using the strike mechanism to voice discontent with broader management practices including the potential capture of independent directors.

| Variables | LnCEOSalary | LnCEOBonus | LnCEOEquity | LnCEOTotal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | |

| IndepDir | −0.500 | −1.332 | 1.608 | 1.779 | 0.607 | 0.585 | −0.151 | −0.485 |

| CEOChair | −0.234 | −0.903 | −1.092 | −1.752 | 0.039 | 0.054 | 0.088 | 0.413 |

| NewCEO | −0.195 | −0.779 | −2.854 | −4.724*** | 0.053 | 0.076 | −0.263 | −1.268 |

| BoardShares% | −0.253 | −0.394 | −0.954 | −0.617 | −3.271 | −1.843 | 0.032 | 0.061 |

| CEOShares% | −2.993 | −4.089*** | −4.403 | −2.499* | −7.552 | −3.732*** | −2.270 | −3.747*** |

| Top20% | 0.005 | 0.822 | 0.006 | 0.426 | −0.008 | −0.496 | 0.007 | 1.538 |

| Loss | −0.430 | −1.835 | −1.970 | −3.495*** | 0.421 | 0.651 | −0.217 | −1.118 |

| MarketRet | 0.144 | 0.779 | 0.235 | 0.525 | 1.150 | 2.242* | 0.069 | 0.452 |

| Leverage | 0.405 | 0.951 | 1.650 | 1.610 | −0.547 | −0.464 | 0.150 | 0.426 |

| BTM | 0.213 | 2.023 | −0.088 | −0.347 | −0.225 | −0.771 | 0.152 | 1.750 |

| LnMCap | 0.195 | 2.954** | 0.840 | 5.296*** | 0.530 | 2.910** | 0.287 | 5.257*** |

| KMP | 0.122 | 3.439** | 0.153 | 1.798 | 0.442 | 4.520*** | 0.108 | 3.684*** |

| Constant | 8.187 | 6.283*** | −11.014 | −3.510** | −7.399 | −2.053* | 6.740 | 6.249*** |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| F-stat | 5.897*** | 11.529*** | 7.061*** | 7.992*** | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 17.8% | 31.8% | 21.2% | 23.7% | ||||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | ||||

- This table presents OLS regressions on CEO pay. Two-tailed test of significance: ***< 0.001, **< 0.01 and *< 0.05.

| Panel A: Strike | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coeff. | p-value | Coeff. | p-value | Coeff. | p-value | Coeff. | p-value |

| LnCEOSalaryPredicted | 0.207 | 0.215 | ||||||

| LnCEOSalaryResidual | 0.030 | 0.567 | ||||||

| LnCEOBonusPredicted | 0.070 | 0.255 | ||||||

| LnCEOBonusResidual | 0.011 | 0.626 | ||||||

| LnCEOEquityPredicted | 0.051 | 0.317 | ||||||

| LnCEOEquityResidual | −0.016 | 0.412 | ||||||

| LnCEOTotalPredicted | 0.182 | 0.217 | ||||||

| LnCEOTotalResidual | 0.046 | 0.462 | ||||||

| IndepDir | 1.041 | 0.012** | 0.814 | 0.050* | 0.891 | 0.029* | 0.968 | 0.018* |

| CEOChair | 0.410 | 0.162 | 0.422 | 0.160 | 0.355 | 0.209 | 0.344 | 0.221 |

| NewCEO | 0.314 | 0.241 | 0.498 | 0.110 | 0.273 | 0.316 | 0.325 | 0.226 |

| BoardShares% | 0.573 | 0.421 | 0.528 | 0.455 | 0.619 | 0.399 | 0.504 | 0.472 |

| CEOShares% | 0.210 | 0.833 | −0.098 | 0.911 | −0.087 | 0.923 | −0.001 | 0.999 |

| Top20% | −0.012 | 0.072 | −0.011 | 0.084 | −0.010 | 0.109 | −0.012 | 0.067 |

| Loss | 0.421 | 0.113 | 0.491 | 0.112 | 0.304 | 0.193 | 0.376 | 0.132 |

| MarketRet | −0.198 | 0.317 | −0.190 | 0.336 | −0.210 | 0.304 | −0.183 | 0.351 |

| Leverage | 0.837 | 0.057 | 0.829 | 0.061 | 0.946 | 0.028* | 0.918 | 0.033* |

| BTM | 0.239 | 0.035* | 0.300 | 0.009* | 0.294 | 0.010** | 0.263 | 0.019* |

| RR% | 4.546 | 0.160 | 4.438 | 0.177 | 5.126 | 0.126 | 4.307 | 0.188 |

| Constant | −3.759 | 0.077 | −1.490 | 0.016* | −1.521 | 0.014* | −3.446 | 0.070 |

| Chi-square | 30.086 | 0.005** | 30.237 | 0.004** | 30.512 | 0.004** | 30.298 | 0.004** |

| Nagelkerke R 2 | 7.7% | 7.6% | 7.7% | 7.8% | ||||

| Classification% | 59.5% | 59.3% | 59.7% | 60.1% | ||||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | ||||

| Panel B: Dissent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat |

| LnCEOSalaryPredicted | 0.019 | 0.977 | ||||||

| LnCEOSalaryResidual | 0.007 | 1.235 | ||||||

| LnCEOBonusPredicted | 0.001 | 0.149 | ||||||

| LnCEOBonusResidual | 0.003 | 1.365 | ||||||

| LnCEOEquityPredicted | 0.003 | 0.571 | ||||||

| LnCEOEquityResidual | −0.002 | −0.915 | ||||||

| LnCEOTotalPredicted | 0.016 | 0.964 | ||||||

| LnCEOTotalResidual | 0.009 | 1.275 | ||||||

| IndepDir | 0.091 | 1.899 | 0.081 | 1.643 | 0.079 | 1.653 | 0.085 | 1.789 |

| CEOChair | 0.033 | 0.969 | 0.024 | 0.685 | 0.027 | 0.831 | 0.027 | 0.823 |

| NewCEO | 0.002 | 0.067 | 0.005 | 0.141 | −0.001 | −0.023 | 0.003 | 0.097 |

| BoardShares% | 0.115 | 1.385 | 0.094 | 1.134 | 0.115 | 1.337 | 0.108 | 1.327 |

| CEOShares% | 0.093 | 0.804 | 0.029 | 0.284 | 0.056 | 0.529 | 0.073 | 0.695 |

| Top20% | −0.001 | −1.916 | −0.001 | −1.697 | −0.001 | −1.765 | −0.001 | −1.928* |

| Loss | 0.060 | 1.960* | 0.049 | 1.361 | 0.049 | 1.796 | 0.056 | 1.932* |

| MarketRet | −0.024 | −1.037 | −0.020 | −0.872 | −0.023 | −0.975 | −0.023 | −0.985 |

| Leverage | 0.128 | 2.524* | 0.138 | 2.693* | 0.138 | 2.787* | 0.136 | 2.736* |

| BTM | 0.051 | 3.887*** | 0.054 | 4.081*** | 0.055 | 4.241*** | 0.053 | 4.143*** |

| RR% | 0.049 | 0.131 | 0.077 | 0.205 | 0.167 | 0.432 | 0.020 | 0.054 |

| Constant | −0.108 | −0.437 | 0.124 | 1.743 | 0.100 | 1.412 | −0.076 | −0.546 |

| F-stat | 2.995*** | 2.948*** | 2.895*** | 2.999*** | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 5.2% | 5.1% | 5.0% | 5.2% | ||||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | ||||

- This table presents logit regressions on receiving a strike (Panel A) and OLS regressions on dissent (Panel B) and predicted and residual CEO pay (from Table 5). Two-tailed test of significance: ***< 0.001, **< 0.01 and *< 0.05.

In conclusion, we find no consistent evidence in support of H1. There is no evidence of shareholders voting in response to total pay or voting in response to excess pay. The two-strikes legislation does not appear to be utilised for targeting excessive management remuneration, but rather to express general shareholder dissatisfaction.

4.3 Changes in CEO pay and receiving a strike

Table 6 examines whether there is an association between changes in CEO pay measures and receiving a strike (Panel A) or dissenting votes (Panel B). To calculate changes in CEO pay, we require sample firms to have compensation data for the year following the strike (e.g. data in 2012 [2013] for 2011 [2012] strike firms). Therefore, our change regressions are run on a sample of 445 firm-year observations. The reduction in sample size is due to 29 sample firms not releasing an annual report in the year following a strike (reasons for not releasing an annual report include delisting from the ASX, and mergers and acquisitions). We find evidence that receiving a strike is associated with a larger decrease in CEO bonus than otherwise and that a greater vote against the remuneration resolution is not associated with changes in CEO pay. Thus, Australian boards who receive a strike seem to respond to shareholder concerns by decreasing the discretionary part of CEO pay by a larger amount than matched firms. Our regression results suggest that strike firms decrease their bonus 57.10 percent more than the non-strike matched firms after controlling for firm characteristics.

| Panel A | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ΔLnCEOSalary | ΔLnCEOBonus | ΔLnCEOShare | ΔLnCEOTotal | ||||

| Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | |

| Strike | 0.116 | 1.125 | −1.054 | −2.198* | 0.340 | 0.628 | −0.044 | −0.817 |

| ΔIndepDir | −0.180 | −0.791 | 0.856 | 0.811 | 0.044 | 0.037 | 0.013 | 0.110 |

| CEOChair | 0.056 | 0.377 | 0.397 | 0.578 | −0.521 | −0.672 | −0.140 | −1.828 |

| NewCEO | −0.282 | −2.229* | −0.124 | −0.211 | −0.202 | −0.305 | −0.230 | −3.512*** |

| ΔBoardShares% | −2.313 | −4.765*** | −0.527 | −0.234 | 0.736 | 0.289 | 0.171 | 0.681 |

| ΔCEOShares% | −1.300 | −1.585 | 6.627 | 1.741 | −1.809 | −0.421 | 0.162 | 0.380 |

| ΔTop20 | −0.004 | −0.585 | −0.003 | −0.094 | −0.035 | −1.040 | 0.003 | 0.750 |

| Loss | −0.112 | −0.859 | 0.241 | 0.399 | −1.181 | −1.729 | −0.065 | −0.966 |

| ΔMarketRet | 0.031 | 0.329 | 0.504 | 1.146 | 0.847 | 1.707 | −0.031 | −0.625 |

| ΔLeverage | 0.128 | 0.352 | −0.307 | −0.182 | −2.934 | −1.539 | 0.147 | 0.776 |

| ΔBTM | 0.018 | 0.627 | 0.024 | 0.179 | −0.217 | −1.406 | 0.006 | 0.369 |

| ΔLnMCap | 0.013 | 0.171 | 0.722 | 1.993* | 0.501 | 1.227 | 0.111 | 2.747** |

| ΔKMP | 0.011 | 0.440 | −0.072 | −0.599 | −0.026 | −0.194 | 0.008 | 0.607 |

| Constant | −0.131 | −0.350 | 0.842 | 0.485 | −0.153 | −0.078 | −0.045 | −0.231 |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| F-stat | 2.147** | 1.217 | 1.710* | 1.974** | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 5.1% | 1.0% | 3.2% | 4.4% | ||||

| N | 445 | 445 | 445 | 445 | ||||

| Panel B | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ΔLnCEOSalary | ΔLnCEOBonus | ΔLnCEOShare | ΔLnCEOTotal | ||||

| Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | |

| Dissent | 0.004 | 1.787 | −0.017 | −1.522 | 0.011 | 0.844 | 0.000 | −0.085 |

| ΔIndepDir | −0.186 | −0.818 | 0.851 | 0.803 | 0.032 | 0.027 | 0.011 | 0.094 |

| CEOChair | 0.048 | 0.326 | 0.441 | 0.640 | −0.541 | −0.698 | −0.139 | −1.811 |

| NewCEO | −0.256 | −2.025* | −0.263 | −0.446 | −0.135 | −0.204 | −0.234 | −3.550*** |

| ΔBoardShares% | −2.333 | −4.823*** | −0.313 | −0.139 | 0.674 | 0.266 | 0.181 | 0.720 |

| ΔCEOShares% | −1.243 | −1.519 | 6.217 | 1.629 | −1.652 | −0.385 | 0.148 | 0.347 |

| ΔTop20 | −0.004 | −0.625 | −0.004 | −0.145 | −0.036 | −1.053 | 0.002 | 0.700 |

| Loss | −0.111 | −0.854 | 0.262 | 0.431 | −1.181 | −1.729 | −0.064 | −0.941 |

| ΔMarketRet | 0.028 | 0.297 | 0.483 | 1.097 | 0.842 | 1.698 | −0.033 | −0.669 |

| ΔLeverage | 0.127 | 0.349 | −0.326 | −0.193 | −2.935 | −1.540 | 0.145 | 0.767 |

| ΔBTM | 0.020 | 0.676 | 0.035 | 0.256 | −0.215 | −1.395 | 0.007 | 0.440 |

| ΔLnMCap | 0.018 | 0.231 | 0.760 | 2.094* | 0.508 | 1.245 | 0.115 | 2.842** |

| ΔKMP | 0.012 | 0.447 | −0.073 | −0.604 | −0.026 | −0.192 | 0.008 | 0.605 |

| Constant | −0.181 | −0.483 | 0.758 | 0.434 | −0.252 | −0.128 | −0.063 | −0.324 |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| F-stat | 2.248** | 1.092 | 1.727* | 1.94** | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 5.6% | 0.4% | 3.3% | 4.2% | ||||

| N | 445 | 445 | 445 | 445 | ||||

- This table presents OLS regressions on receiving a strike and changes in CEO pay. Two-tailed test of significance: ***< 0.001, **< 0.01 and *< 0.05.

Our results suggest that the legislation has an effect consistent with its aim, reducing CEO pay that is considered by shareholders to be ‘too high,’ supporting H2. However, we did not find that strike firms receive higher excess pay. Thus, if CEO pay was at the optimal level prior to the strike, then receiving a strike may have caused some firms to underpay CEOs relative to the optimum. Therefore, the legislation may have had the unintended consequence of reducing CEO pay, rather than specifically targeting excess pay.

4.4 Changes in remuneration disclosure and receiving a strike

Table 7 shows the consequences of receiving a strike on changes in the remuneration report. We find that receiving a strike (Strike) and increased shareholder dissent (Dissent) are associated with a greater increase in the size of the remuneration report, both in terms of absolute length and the percentage of the annual report devoted to the remuneration report. On average, firms that receive a strike increase the size of their audited remuneration report by 0.77 pages in length. This represents a 10.95 percent increase in the size of a strike firm's audited remuneration report, relative to the year of the strike. Thus, we find support for H3 that firms increase disclosure in response to shareholder discontent. Out of our control variables, we only find evidence that Loss and CEOChair are associated with a smaller change in remuneration disclosure. We conclude that receiving a strike is the main driver of firms increasing their remuneration disclosure. However, Tables 3 and 5 show that remuneration disclosure is not associated with receiving a strike. Thus, increasing disclosure may be an ineffective response to shareholder discontent.

| Variables | ΔRRLength | ΔRRLength | ΔRR% | ΔRR% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | |

| Strike | 0.773 | 3.539*** | 0.007 | 2.932** | ||||

| Dissent | 1.034 | 2.252* | 0.010 | 2.029* | ||||

| ΔIndepDir | −0.526 | −1.092 | −0.492 | −1.013 | −0.008 | −1.618 | −0.008 | −1.551 |

| CEOChair | −0.744 | −2.382* | −0.782 | −2.484* | −0.005 | −1.598 | −0.005 | −1.696 |

| NewCEO | 0.293 | 1.095 | 0.329 | 1.219 | 0.002 | 0.748 | 0.002 | 0.852 |

| ΔBoardShares% | −0.314 | −0.305 | −0.363 | −0.349 | −0.002 | −0.216 | −0.003 | −0.246 |

| ΔCEOShares% | 0.127 | 0.073 | 0.217 | 0.123 | −0.002 | −0.092 | −0.001 | −0.053 |

| ΔTop20% | −0.006 | −0.400 | −0.005 | −0.331 | 0.000 | −0.502 | 0.000 | −0.454 |

| Loss | −0.726 | −2.858** | −0.744 | −2.907** | −0.005 | −1.790 | −0.005 | −1.838 |

| ΔMarketRet | −0.084 | −0.420 | −0.080 | −0.399 | 0.001 | 0.672 | 0.001 | 0.670 |

| ΔLeverage | 0.450 | 0.587 | 0.449 | 0.581 | −0.003 | −0.343 | −0.003 | −0.345 |

| ΔBTM | 0.045 | 0.727 | 0.037 | 0.595 | 0.000 | −0.315 | 0.000 | −0.407 |

| ΔLnMCap | 0.290 | 1.748 | 0.267 | 1.592 | 0.000 | −0.100 | 0.000 | −0.200 |

| ΔKMP | 0.020 | 0.354 | 0.016 | 0.292 | 0.000 | 0.196 | 0.000 | 0.141 |

| Constant | 0.820 | 3.539*** | 0.954 | 4.081*** | 0.006 | 2.497* | 0.007 | 2.898** |

| F-stat | 2.765** | 2.182** | 1.628 | 1.273 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 4.9% | 3.3% | 1.8% | 0.0% | ||||

| N | 445 | 445 | 445 | 445 | ||||

- This table presents OLS regressions on receiving a strike and changes in remuneration. Two-tailed test of significance: ***< 0.001, **< 0.01 and *< 0.05.

4.5 Additional tests

In unreported tests, we rerun Equation 1 on a sample of firms from 2009 and 2010 who received more than 25 percent of shareholder dissent against the remuneration resolution, which we categorise as pseudo-strike firms, relative to matched non pseudo-strike firms. In these tests, we find that CEO pay is associated with both a ‘pseudo-strike’ (CEO salary and total pay) and dissent (CEO salary, bonus and total pay). When we calculate measures of predicted and residual pay (Equation 3), we find consistent results for the residual pay measures. We infer that the two-strike regulation change in 2011 and the low threshold (25 percent and restricted voting) may make the two-strikes rule an attractive mechanism for non-remuneration-related shareholder activism.

We also investigate the frequency of subsequent strikes following an initial strike. A total of 248 strikes were received in 2011–2012 by 223 firms. In 2011, 118 first strikes were recorded, of which only 25 firms, or 21 percent, received a second strike in the following year. In 2012, 130 strikes were recorded, of which 19 (18 percent) received a second strike in the following year (of 2013 outside of our sample period). Of those 44 second strikes across 2 years, only eight went on to receive a third strike at the subsequent spill vote (forcing the re-election of directors). In total, only three boards (1 percent) were replaced by new directors following an initial strike. When we control for whether the firm has received a previous strike, the results of our tests are unchanged.

We produce similar results when we rerun tests on a subsample of matched pairs with continual data across 2011 and 2012. When we run tests winsorising the top and bottom 5 percent of all variables, results are similar. Our results on the determinants of receiving a strike are unchanged when we use RRLength instead of RR%. Our general findings are also similar when we replace CEO pay with KMP remuneration scaled by the number of KMP.

5 Conclusions

This study examines the Australian ‘two-strikes’ say on pay regulation. In contrast to other say on pay laws, the board cannot vote, and a 25 percent vote against is enough for a ‘strike’ with two strikes in a row leading to an automatic board spill and a vote on a new board (strike three). We find that no measure of CEO pay (salary, bonus, equity, total or ‘excess’) is associated with receiving a strike. Instead, shareholder dissent against the remuneration resolution is associated with higher BTM and leverage ratios. Thus, shareholders seem to use the vote on remuneration reports to vote against sustained bad performance.

We also find that receiving a strike is associated with consequences for CEO pay after controlling for firm characteristics. Firms that receive a strike are likely to have on average a 57.10 percent larger decrease in the CEO's bonus, which is typically the more easily changed component of remuneration. This may suggest that receiving a strike is an effective governance mechanism for monitoring, and reining in excessive discretionary CEO pay. However, if the CEO pay of strike firms was not excessive, reducing future pay may be an inappropriate response to shareholder concerns and thus result in a suboptimal remuneration situation. Next, we find consistent evidence that firms receiving a strike increase their remuneration disclosure by 0.77 pages in length. This represents a 10.95 percent increase in the size of a strike firm's audited remuneration report, relative to the year of the strike. Thus, firms appear more likely to try and explain remuneration than change contracted pay post-strike. The effectiveness of a disclosure-based strategy is questionable considering remuneration disclosure was not associated with receiving a strike.