Against the tide: the commencement of short selling and margin trading in mainland China

We thank seminar participants at the Victoria University of Wellington, the 2012 New Zealand Finance Colloquium PhD Symposium, our discussant, Russell Poskitt, Henk Berkman, the editor who handled this submission, and an anonymous referee for useful comments. All errors are our own. This paper is based on the first chapter of Saqib Sharif's PhD thesis.

Abstract

China's recent removal of short-selling and margin trading bans on selected stocks enables testing of the relative effect of margin trading and short selling. We find the prices of the shortable stocks decrease, on average, relative to peer A-shares and cross-listed H-shares, suggesting that short selling dominates margin trading effects. Contrary to the regulators' intention and recent developed market empirical evidence, liquidity declines and bid-ask spreads increase in these shortable stocks. Consistent with Ausubel (1990), these results imply that uninformed investors avoid the shortable stocks to reduce the risk of trading with informed investors.

1. Introduction

On 31 March 2010, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) permitted margin trading and securities lending for the first time.1 The launch of short selling in China occurred at a time when market regulators around the world were restricting short-selling activities, especially on financial sector stocks.2 This allows us to document the impact of a country ‘swimming against the tide’ of international regulation. We examine the effect of margin trading and short sales on relative prices, liquidity, and volatility, using data from Mainland China and Hong Kong.

We contribute to the literature in several ways.3 Firstly, the dual introduction of short selling and margin trading allows us to assess the relative impact of each. We find that the impact of allowing short sales is the stronger of the two. It seems that it is the heightened risk of trading against informed investors that is driving this result. Secondly, we document the introduction of short selling and margin trading on liquidity in an emerging market. These issues have received relatively little attention in emerging markets compared with developed markets. Emerging markets evidence may be different to that from developed markets due to factors such as weaker investor protection (e.g. Morck et al., 2000). Contrary to both the regulator's intention and evidence from developed markets, this change in regulation resulted in decreased liquidity. This implies that investors avoid the stocks the regulation relates to. Thirdly, there is only limited evidence on the impact of short sales and margin trading on stock returns in emerging markets. Lee and Yoo (1993) find no relationship between margin requirements and stock return volatility in Korea and Taiwan, while Lamba and Ariff (2006) find return increases following the relaxation of short-sale constraints in Malaysia.

We use two matching procedures. The first involves matching eligible A-share (pilot programme companies) with ineligible A-share companies (referred to as the M-shares hereafter in the paper) which have similar characteristics, while the second uses the pilot programme cross-listed H-shares. Our main results are robust to both matching methods and the length of pre- and postperiod used. We show the short-selling effect dominates the margin trading effect. In the postperiod, the prices of A-shares eligible for short selling and margin trading decrease more than those of noneligible M-shares (or matched H-shares). As a consequence, the A-M (A-H) premium4 becomes smaller in the postperiod. These results are consistent with the theoretical models of Miller (1977) and Chen et al. (2002) which suggest short-sale restrictions tend to inflate prices. However, in contrast to these models, which imply that it is the actions of short sellers that drive prices lower, our results suggest that, consistent with Ausubel (1990), it is the risk of trading against informed investors, in this case short sellers, that lead to the price reduction. Our results are also in accordance with Chan et al. (2010) who show the premium of Chinese-listed stocks over their dual listed Hong Kong equivalents becomes relatively larger during market declines, for stocks where H-shares can be short sold. While the reduction in margin requirements might be expected to increase the relative prices (and premiums) of eligible A-shares, Chinese investors with positive information could already trade prior to the regulation change by borrowing with credit cards and house mortgage agreements (Tarantino, 2008).

We also explore the impact of margin trading and short selling of the eligible A-shares on the trading value ratio between A-share and M-share (H-share) trading value. On announcing the plans to launch the pilot programme, the CSRC's chief motivation is ‘to enlarge the supply and demand of funds and securities and increase the trading volume, thus leading to active liquidity’.5 This motivation is consistent with the finding of most empirical studies. Kolasinksi et al. (2009) and Boehmer et al. (2009) document liquidity declines in stocks which have short-sale bans imposed. Moreover, margin trading papers such as Seguin (1990) and Hardouvelis and Peristiani (1992) find that lower (higher) margin requirements lead to an increase (decrease) in liquidity.

In contrast to CSRC's motivation and the prior literature, we find both absolute and relative liquidity decreases for the pilot programme stocks. Liquidity in Chinese market in general declined in the period we consider, but we show additional declines in pilot stock liquidity. This is not unexpected as the asymmetric information risk increases for the 89 pilot programme stocks enabling insiders with either negative or positive insider information to exploit the asymmetric information more effectively through short selling and margin trading, respectively.6 Ausubel (1990) argues that ‘if ‘outsiders’ expect ‘insiders’ to take advantage of them in trading, outsiders will reduce their investment’ (p. 1022).7 Similarly, uninformed investors may seek to reduce their risk of losses to informed investors by only trading to meet their liquidity requirements (Admati and Pfleiderer, 1988). As the pilot programme is effective for only 89 stocks (approximately 6.7 per cent of all A-shares), uninformed investors may be able to find appropriate substitute nonpilot stocks to invest in thereby reducing their asymmetric information risk.

Chakravarty et al. (1998) suggest that insider trading is common in China. Therefore, our results point to ‘outsiders’ being aware of these facts and directing their trading activity away from the pilot programme stocks as a result. We also find that the frequency and level of short sales are very low. The mean pilot stock has short-sales activity on just 8 per cent of days, and, on average, short-sales activity relates to just 0.01 per cent of volume. This indicates that the additional trading volume directly associated with short-selling and margin trading activity is dwarfed by the reduction in normal trading activity for these pilot stocks. Further, the decline in premium of pilot stocks is more likely due to short-sale risk rather than short-sale activity.

We find some evidence that the spreads of pilot securities increase, relative to peer firms, after the introduction of margin trading and short selling. This exists in the A-H results but not in the A-M results. This result contrasts with Autore et al. (2011), Beber and Pagano (2013) and Boehmer et al. (2009), who each show that short-sales bans during the global financial crisis lead to wider bid-ask spreads. However, our spread results are consistent with our trading value results. A decrease in trading value and increased spreads both point to a decrease in overall liquidity for the pilot stocks following the introduction of short selling and margin trading.

Previous literature has not formed a consensus on the relation between short selling and/or margin trading and volatility. Scheinkman and Xiong (2003) suggest short-sale constraints may result in increased price volatility. However, Chang et al. (2007) find higher volatility in individual stocks when short selling is practised. Seguin (1990) finds a decrease in volatility when margin trading is allowed, but Hardouvelis and Peristiani (1992) find lower volatility in stocks when margin requirements are increased. Our volatility results are less consistent than those for the other variable; however, the majority of evidence points to a reduction in volatility.

From a public policy perspective, our findings suggest that the introduction of margin trading and short selling aids in the price discovery process. In particular, short selling allows for the first time in China investors with a pessimistic outlook for a firm to have their views incorporated into stocks prices. However, the regulation change does not boost the liquidity of the pilot programme securities, as anticipated by the regulators. In fact, liquidity as measured by spread and daily trading value deteriorate for pilot stocks.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 contains background on short-sales and margin trading regulations in China; our hypotheses are motivated and stated in Section 3; the Data and Methodology are outlined in Section 4; the results are discussed in Section 5; and Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Chinese margin trading and short-sales regulation

The purpose of introducing the pilot programme of margin trading and short sales by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) is ‘to integrate more information into securities prices. So investors can conduct securities lending or margin trading when the stock price is high or low, thus forming more proper stock prices’.8 The change in regulations to allow margin trading and short selling were discussed by the CSRC as early as 2006 (Bryan et al., 2010). In October 2008, the CSRC announced that there would soon be a margin trading and securities lending trial. However, it was not until 8 January 2010 that China's State Council gave the ‘in principle’ approval to introduce margin trading and security lending on a trial basis (Bryan et al., 2010). Then on 12 February 2010, the CSRC announced the first details of the stocks that would be part of a pilot programme for margin trading and short-selling operations (Bryan et al., 2010). Under the programme, CSRC approved 90 blue-chip securities for margin trading and securities lending including 50 from the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) and 40 from the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE). The pilot programme was formally launched on 31 March 2010 (Bryan et al., 2010). The implementation rules are given in Appendix I, and the list of 90 stocks targeted for margin trading and short selling are reported in Appendix II.

3. Hypotheses development

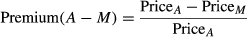

The first hypothesis relates to the effect of short selling and margin trading on the prices of stocks in the pilot programme relative to the price of peer stocks listed in China and cross-listed stocks in Hong Kong. We measure the A-M (A-H) ‘premium’ as the difference in A-share and M-share (H-share) prices, divided by the A-share price. It is well documented that Chinese-listed firms trade at a premium to their Hong Kong-listed equivalents (e.g. Chan et al., 2010). The A-H premium is therefore expected to be positive. For the sake of consistency, we refer to the difference between A and M prices (relative to the A price) as a ‘premium’. However, as the M companies are simply Chinese-listed firms with similar characteristics to their A company counterparts, this ‘premium’ may be negative. This does not affect our analysis as we are focused on the change in premium following the regulation and the hypothesized direction of the change should be the same in both the A-M and A-H samples.

The introduction of short sales is expected to result in a decrease in the price of pilot companies relative to their peers. The theoretical models of Miller (1977) and Chen et al. (2002) show that short-sale constraints result in overvaluation as pessimistic investors are prevented from entering the market. The empirical work of Jones and Lamont (2002), Ofek and Richardson (2003), Chang et al. (2007) and Chan et al. (2010) also finds that short-sale constraints lead to higher relative prices. Hence, removing these constraints (i.e. allowing short sales) on pilot stocks should be expected to results in a decrease in their price relative to peer firms.

Conversely, allowing margin trading permits cash-constrained investors with a positive view on a stock price to trade. This implies the price of pilot firms should be higher, relative to their peers, following the regulation change. Largay (1973) and Hardouvelis and Peristiani (1992) both find that the margin size requirement is negatively related to price movements. In the case of China, margin requirements on pilot stocks declined from 100 per cent to a lesser amount so the relative price response of pilot firms should be positive. However, the margin buying effect on pilot stock prices may be limited in case of China, as the optimistic investors can invest in shares by borrowing against house and other assets before the implementation (Tarantino, 2008). Based on the literature discussed above, our two hypotheses are:

- H1A : The A-M and A-H premium is lower when short selling is allowed.

- H1B : A-M and A-H premium is higher when margin trading is allowed.

- H2 : The eligible A-shares proportion of trading value increases when margin trading and short selling are allowed.

However, empirical results from emerging markets may vary from their developed market equivalents (e.g. Morck et al., 2000). Following the implementation of pilot programme, less-informed investors are likely to be reluctant to invest in pilot stocks if, as suggested by Asubel (1990), they believe there is more chance of trading against informed investors. The regulators in China set high entry requirements for investors to participate in pilot margin trading and short selling (Wang, 2011). This suggests it is likely that it is mostly better informed institutional investors who short sell and margin trade. The risks to uninformed investors are exacerbated by the well-documented insider trading and investor protection issues in China (e.g. Chakravarty et al., 1998). Given the above, it is possible that, consistent with the findings of Ausubel (1990), liquidity declines in pilot programme stocks.

- H3 : The A-M and A-H relative bid-ask spread differentials decrease when margin trading and short selling are allowed.

- H4 : There is no change to the A-M and A-H relative volatility differential when margin trading and short selling are allowed.

4. Data and methodology

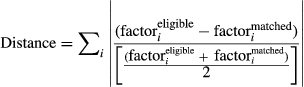

Our study covers the period from 1 October 2009 through 30 June 2010. This is split into a 3-month preperiod of October 1–December 31 and a 3-month postperiod of March 31–June 30.9 We decide against using the 3-month preperiod of 1 January to 30 March 2010 due to the contaminating announcement of the launch of pilot programme on 12 February 2010. Henan Shuanghui Investment and Development Co., Ltd did not trade from 22 March 2010 to 26 November 2010 and therefore is excluded. The final sample therefore includes 89 pilot stocks that were part of the margin trading and short-selling pilot programme. Fifty are listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE), and 39 are listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE). We also conduct robustness tests around period length and start points, which we discuss in more detail in the results section. Some firms were removed from the pilot short-selling and margin trading programme after 30 June 2010 so longer postperiods involve a reduction in stock numbers. Data on closing stock prices, trading volume, bid-ask spread, high/low volatility, market capitalization and number of shares outstanding at daily level for A-shares and H-shares are obtained from Thomson Reuters Datastream. The stock market index, including SSE A-share Index, and currency exchange rate between Chinese RMB and Hong Kong Dollar are also obtained from Thomson Reuters Datastream. Further, we obtain the daily short-selling and margin trading data from Chinese Securities Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR).

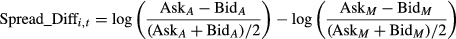

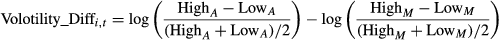

(1)

(1)The second matching procedure involves sourcing data for the Hong Kong-listed share of each of the 89 pilot programme stocks. Using data from the Website of Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx), we find that 26 of the 89 companies have shares listed in Hong Kong. The matching procedures each have their strengths and weaknesses. The first matching procedure has the advantage of using firms trading on the same exchange; however, the disadvantage is that it is not always possible to find a matched firm of a similar size.12 The second matching procedure uses prices of the same company; however, the exchange is different. These two approaches therefore complement each other.

(2)

(2) (3)

(3)5. Empirical results

5.1 Univariate analysis

In Table 1, we present the mean and median levels for each of our variables of interest in the 3-month pre- and postperiods. All analysis is carried out for the sample of 89 pilot firms and 89 matched equivalent companies listed in China (M-shares) and for 26 of the pilot firms, which can be matched with their Hong Kong-listed shares data. We calculate changes for pilot firms in Panels A and D and their matched peer firms in Panels B and D, but the most insightful results are in Panels C and F. This contain changes in the differences between pilot and peer firms.

| Mean | Median | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Diff | p-value | Pre | Post | Diff | p-value | |

| Panel A: Affected sample (N = 89) | ||||||||

| Price_A | 21.0969 | 18.0773 | −3.0196 | 0.0001 | 15.6200 | 12.9100 | −2.7100 | 0.0001 |

| Value_A | 717.9164 | 395.6796 | −322.2370 | 0.0001 | 519.2247 | 287.4420 | −231.7827 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_A | −7.2682 | −7.0879 | 0.1803 | 0.0001 | −7.2651 | −7.0947 | 0.1704 | 0.0001 |

| Volatility_A | −3.4774 | −3.4727 | 0.0047 | 0.6095 | −3.4916 | −3.4666 | 0.0251 | 0.1696 |

| Panel B: Matched sample (N = 89) | ||||||||

| Price_M | 18.2824 | 16.4327 | −1.8497 | 0.0001 | 16.3900 | 13.3600 | −3.0300 | 0.0001 |

| Value_M | 227.2960 | 147.1536 | −80.1424 | 0.0001 | 173.0580 | 96.3359 | −76.7221 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_M | −7.1675 | −7.0112 | 0.1563 | 0.0001 | −7.2503 | −7.0566 | 0.1937 | 0.0001 |

| Volatility_M | −3.4074 | −3.3481 | 0.0593 | 0.0001 | −3.4237 | −3.3313 | 0.0924 | 0.0001 |

| Panel C: Affected – matched sample | ||||||||

| Premium | −0.0441 | −0.1051 | −0.0610 | 0.0001 | −0.0174 | −0.0065 | 0.0109 | 0.0250 |

| Value_Ratio | 0.7296 | 0.7031 | −0.0265 | 0.0001 | 0.7449 | 0.7208 | −0.0241 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_Diff | −0.1087 | −0.0923 | 0.0164 | 0.2462 | −0.0276 | −0.0331 | −0.0055 | 0.2947 |

| Volatility_Diff | −0.0721 | −0.1275 | −0.0553 | 0.0001 | −0.0660 | −0.1380 | −0.0721 | 0.0001 |

| Panel D: Affected sample – A-shares (N = 26) | ||||||||

| Price_A | 17.7233 | 15.1802 | −2.5431 | 0.0001 | 12.8350 | 9.7900 | −3.0450 | 0.0001 |

| Value_A | 783.2905 | 426.8246 | −356.4660 | 0.0001 | 593.6255 | 308.5567 | −285.0688 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_A | −7.0603 | −6.8993 | 0.1610 | 0.0001 | −6.9546 | −6.8007 | 0.1539 | 0.0001 |

| Volatility_A | −3.5782 | −3.6003 | −0.0221 | 0.2020 | −3.6054 | −3.6063 | −0.0008 | 0.2890 |

| Panel E: Matched sample – H-shares (N = 26) | ||||||||

| Price_H | 14.7497 | 13.9415 | −0.8082 | 0.1365 | 8.1505 | 7.4461 | −0.7044 | 0.0029 |

| Value_H | 575.6409 | 501.3429 | −74.2980 | 0.0027 | 308.5068 | 274.7565 | −33.7503 | 0.0583 |

| Spread_H | −6.1821 | −6.1644 | 0.0178 | 0.4155 | −6.2719 | −6.3395 | −0.0675 | 0.2739 |

| Volatility_H | −3.6022 | −3.6038 | −0.0017 | 0.9209 | −3.6095 | −3.6092 | 0.0003 | 0.8785 |

| Panel F: Affected – matched sample | ||||||||

| Premium | 0.1971 | 0.1090 | −0.0882 | 0.0001 | 0.1102 | 0.0320 | −0.0782 | 0.0001 |

| Value_Ratio | 0.6377 | 0.5282 | −0.1095 | 0.0001 | 0.6935 | 0.5545 | −0.1390 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_Diff | −0.8722 | −0.7341 | 0.1382 | 0.0001 | −0.7552 | −0.5785 | 0.1766 | 0.0001 |

| Volatility_Diff | 0.0316 | 0.0043 | −0.0272 | 0.1528 | 0.0417 | 0.0138 | −0.0279 | 0.2621 |

- This table reports the mean and median of several variables and their differences. In Panel A, the mean and median of each variable is measured for affected sample from 1 October 2009 through 31 December 2009 (before the launch of margin trading and short-sale pilot programme in Mainland China, that is, preperiod) and from 31 March 2010 through 30 June 2010 (after the launch of short-sale and margin trading pilot programme in Mainland China, that is, postperiod) along with difference in means, medians and their p-values. In Panel B. the means and medians of each variable are measured for all matched A-shares not included in the pilot programme. Panel C is the difference between affected and matched sample. In Panel D, the mean and median of each variable is measured for affected A-shares from 1 October 2009 through 31 December 2009 (i.e. preperiod) and from 31 March 2010 through 30 June 2010 (i.e. postperiod) along with difference in means, medians and their p-values. In Panel E, the means and medians of each variable are measured for cross-listed H-shares. Panel F reports the difference between A- and H-shares.

Panels C and F show the mean A-share premium declines after the regulation allowing short sales and margin trading is introduced. This falls by 6.1 per cent and 8.8 per cent compared with matched M and H-shares, respectively. Both these declines are statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. The other four panels show that prices of Chinese stocks declined on average in the postperiod compared with the preperiod, but the pilot stock prices declined by more than their matched peers. Short selling can be expected to drive prices lower, while margin trading is likely to have a positive impact on prices. The premium results therefore indicate that the short-selling effect is the stronger of the two and provides support for hypothesis 1A.

The value ratios, as shown in Panels C and F, also decline in the postperiod. This indicates the RMB volume (value) of trading in pilot programme stocks declined relative to M and H stock value following the regulation. The other panels show that the value of trades in A, M and H stocks was lower in the period following the introduction of the regulation, but, as indicated in Panels C and F, the decline was proportionally larger in A stocks. This result runs counter to our hypothesis 2. Like the regulators who introduced the regulation, we expected both margin trading and short selling to result in an increase in liquidity. Our finding is, however, consistent with the proposition of Ausubel (1990). He suggests that uninformed investors may decide not to trade if they are concerned they will be trading with an investor with superior information. Allowing short selling and margin trading give informed investors more opportunity to exploit their informational advantage so it is possible this scares less well-informed investors away.

The bid-ask spread of A stocks relative to M stocks does not change following the regulation. However, the A-H spread differential increases. This runs contrary to our hypothesis 3 that spreads would decrease due to an increase in liquidity, but it is consistent with our trading value results. The decline in trading value and an increase in spreads both suggest a decrease in overall liquidity. The volatility results are inconclusive. A-share volatility decreases relative to M-share volatility after the regulation but does not change relative to H-share volatility.15

We generate results for different pre- and postperiods to ensure our premium, value and spread conclusions are not specific to the period we focus on.16 They are not. In Appendix III, we present results for a 6-month preperiod (1 July 2009–31 December 2009) and a 6-month postperiod (31 March 2010–30 September 2010). These results are qualitatively identical to their Table 1 equivalents. However, the volatility result is strengthened. There is evidence of a decline in volatility in not only the M-share match results but also the H-share match results.

5.2 Short-sales and margin trading activity summary statistics

We present statistics relating to the level and frequency of short-sales and margin trading activity in Table 2. The short-sales (margin trading) ratio is the ratio of short sales (margin trading) to total volume. This is calculated each day for each stock. A time series average is then computed for each stock, and summary statistics are based on the stock average numbers. The proportions relate to the fraction of days there is short-sales or margin trading activity, respectively, in each stock. Again, statistics are based on the stock numbers.

| Variable | Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-sale ratio | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0019 | 0.0003 |

| Margin trading ratio | 0.0021 | 0.0018 | 0.0003 | 0.0084 | 0.0014 |

| Short-sale proportion | 0.0794 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.8305 | 0.1563 |

| Margin trading proportion | 0.6629 | 0.6833 | 0.2333 | 0.9322 | 0.1659 |

- These statistics relate to the stocks that were allowed to be sold short and traded on margin between 31 March 2010 and 30 June 2010. The short-sale (margin trading) ratio relate to the short-sale (margin trading) volume divided by total volume. This time series average is calculated for each stock, and cross-sectional statistics are then calculated. The short-sale (margin trading) proportion is the proportion of days when there is short sales (margin trading) activity. Statistics are calculated across all stocks.

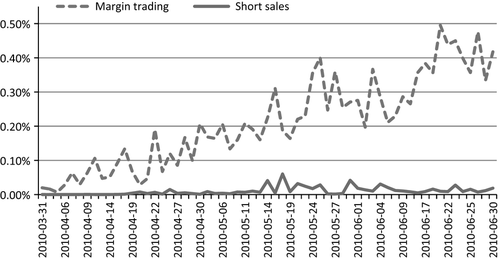

The Table 2 results indicate short sales and margin trades only account for a small fraction of the volume traded in each pilot stock in the 3-month period following the regulation change. Short sales contribute just 0.01 per cent of the total volume for the average stock. Margin trades contribute just 0.2 per cent on average. This lack of activity is reasonably consistent across stocks. The stock with the most short sales (margin trading) activity has just 0.19 per cent (0.84 per cent) of volume driven by this activity. The proportion of days with short-sales activity is just 7.9 per cent for the average stock. The equivalent number is considerably higher for margin trading (66.3 per cent), which indicates a reasonably high frequency. Figure 1 shows the proportion of average daily volume that relates to short sales and margin trading in the 3-month period following the regulation change. While margin trading activities show growth over the period, short sales do not and clearly the trades are small and relatively inconsequential when compared with total volume.

These results clearly indicate that the decline in premium in Table 1 is not due to the short sellers driving prices down. Rather, it appears to be a result of market participants being concerned about the potential for short sellers to drive prices lower. This concern appears to manifest itself in investors reducing their trading in pilot stocks, which combined with the increased asymmetric information risk results in an increase in spreads. We address these issues in the next section on multivariate analysis.

5.3 Multivariate analysis

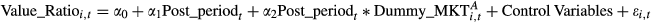

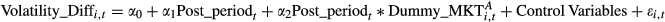

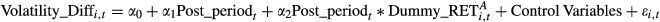

A multivariate fixed effect panel regression framework is employed to test whether the introduction of margin purchases and securities lending has any effect on eligible A-shares in mainland China.

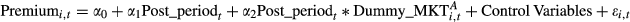

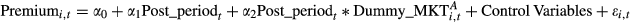

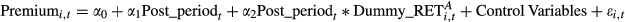

5.3.1 Premium

()

() ()

()The main result of the regression analysis is that the A-M (A-H) premium is negatively related to the postperiod dummy and the interaction term as shown in Model (1)A, (1)B, and (1)C of Panels A and B. This is consistent with our hypothesis 1A that the premium becomes smaller when short selling is allowed in China. Further, this effect of smaller premiums is more pronounced on days when the Chinese stock markets decline. The evidence also suggests that the effect of short sellers dominates the Chinese market as compared to margin purchasers during the period examined.

The results of some control variables are inconsistent with expectations. For example, in Model (1)E of Panel A, the evidence indicates that the A-M premium is negatively associated with M-share volatility, suggesting that an increase in M-share volatility is accompanied by an increase in M-share prices and, thus, a decline in the A-M premium. Furthermore, in Model (1)E of Panel B, only one estimation model with control variables has significant and consistent results with what we expected. That is, the A-H premium is positively associated with H-share volatility, suggesting that an increase in H-share volatility is accompanied by a decrease in H-share prices and, thus, the A-H premium increases.

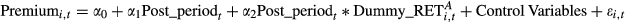

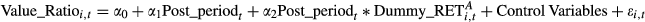

5.3.2 Trading value ratio

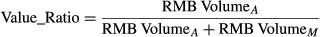

We test hypothesis 2 that A-M (A-H) value ratio is higher for those A-shares allowed for margin trading and short selling than for those ineligible in China, that is, matched M-shares and shortable H-shares in Hong Kong.17 We estimate regression models similar to Equations (6a) and (6b), except that the dependent variable is Value_Ratioi,t.

The results are presented in Panels A and B of Table 4. The key variable of interest is the postperiod and the interaction term. Similar to our univariate results, we find evidence contrary to our hypothesis 2; the coefficient on the postperiod dummy and the interaction term is significantly negative in Model (1)A and (1)B of Panels A and B. This means that A-share trading value declined relative to M-share (H-share) following the introduction of the pilot programme. Similarly, when the A-share market goes down, for the group of affected A-share stocks, there is a decline of A-share trading value relative to M-share (H-share) trading value. Our results are inconsistent with the literature that documents liquidity increases when short-sale constraints and margin requirements are reduced. However, the evidence is consistent with the model of Ausubel (1990) as uninformed investors reduce their exposure to the increased asymmetric information risk by reducing trading activity or simply avoiding the 89 pilot stocks.

Unlike the regression results in Panels A and B of Table 3, where Premiumi,t is used as the dependent variable, the coefficients associated with the control variables in Panel A and B of Table 4 are highly significant. We find that the Value_Ratioi,t is positively related to M-share (H-share) bid-ask spread and positively (negatively) related to A-share (M-share) volatility.

| SSE A-share index | Individual A-share | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1)A | (1)B | (1)C | (1)D | (1)E | (2)B | (2)C | (2)D | (2)E | |

| Panel A: China match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

−0.0610** (−2.25) |

−0.0584** (−2.22) |

−0.0067 (−0.27) |

−0.0564** (−2.17) |

−0.0528** (−1.96) |

−0.0050 (−0.20) |

−0.0501* (−1.88) |

||

| Post_period*Down_dummy |

−0.0461** (−2.29) |

−0.0043** (−2.04) |

0.0053 (1.14) |

−0.0060 (−1.14) |

−0.0512** (−2.36) |

−0.0152 (−1.12) |

0.0026 (0.27) |

−0.0184 (−1.33) |

|

| Relative bid-ask spread (A-share) |

−0.2794*** (−5.38) |

−0.2794*** (−5.38) |

|||||||

| Relative bid-ask spread (M-share) |

0.0651 (1.40) |

0.0655 (1.41) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (A-share) |

−0.0196 (−0.53) |

−0.0195 (−0.53) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (M-share) |

−0.1410*** (−3.17) |

−0.1411*** (3.18) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

−0.0441 (−1.06) |

−0.0608 (−1.40) |

−0.0441 (−1.06) |

−2.1461*** (−5.15) |

−0.0555 (−0.17) |

−0.0608 (−1.39) |

−0.0441 (−1.06) |

−2.1458*** (−5.15) |

−0.0536 (−0.16) |

| Observations | 10 890 | 10 890 | 10 890 | 9851 | 10 249 | 10 890 | 10 890 | 9851 | 10 249 |

| R-Squared | 0.0044 | 0.0021 | 0.0044 | 0.1698 | 0.0369 | 0.0025 | 0.0045 | 0.1698 | 0.0370 |

| Panel B: Hong Kong match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

−0.0885*** (−5.96) |

−0.0840*** (−5.70) |

−0.0840*** (−4.35) |

−0.0862*** (−5.83) |

−0.0940*** (−5.03) |

−0.0928*** (−4.48) |

−0.0941*** (−5.15) |

||

| Post_period*Down_dummy |

−0.0678*** (−6.48) |

−0.0071*** (−5.77) |

−0.0063* (−1.92) |

−0.0048 (−1.40) |

−0.0550*** (−4.42) |

0.0096 (0.60) |

0.0082 (0.52) |

0.0084 (0.59) |

|

| Relative bid-ask spread (A-share) |

0.0217 (0.41) |

0.0215 (0.41) |

|||||||

| Relative bid-ask spread (H-share) |

0.0793 (1.59) |

0.0792 (1.58) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (A-share) |

0.1001** (2.08) |

0.1002** (2.09) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (H-share) |

0.0706* (1.77) |

0.0708* (1.78) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

0.1975*** (4.04) |

0.1742*** (3.53) |

0.1975*** (4.04) |

0.7106 (1.61) |

0.9422** (2.42) |

0.1681*** (3.37) |

0.1975*** (4.04) |

0.7099 (1.60) |

0.9423** (2.42) |

| Observations | 2931 | 2931 | 2931 | 2828 | 2926 | 2931 | 2931 | 2828 | 2926 |

| R-Squared | 0.0295 | 0.0153 | 0.0296 | 0.0623 | 0.0860 | 0.0095 | 0.0296 | 0.0624 | 0.0861 |

- Panel A (B) reports the results of fixed-effects panel regressions for the 89 (26) pilot and M (H) matched stocks. The dependent variable is premium, which is calculated for each stock as (pilot stock price – matched stock price)/pilot stock price. The sample period is from 1 October 2009 to 30 June 2010. Post_period is a dummy variable that is equal to one for the period from 31 March 2010 to 30 June 2010 and zero otherwise. Post_period*Down_dummy is an interaction dummy variable set to one, when the return of A-share market (MKTA) in Models 1 and individual pilot A-share (RETA) in Models 2 is less than 0 during the postperiod and zero otherwise.

- The t-value is adjusted by the Rogers standard error clustered by firm. *, ** and *** indicate significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level, respectively.

| SSE A-share index | Individual A-share | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1)A | (1)B | (1)C | (1)D | (1)E | (2)B | (2)C | (2)D | (2)E | |

| Panel A: China match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

−0.0265 (−2.33) |

−0.0252** (−2.25) |

−0.0233** (−1.99) |

−0.0238** (−2.16) |

−0.0207* (−1.85) |

−0.0193* (−1.67) |

−0.0180* (−1.68) |

||

| Post_period*Down_dummy |

−0.0203** (−2.36) |

−0.0022 (−0.77) |

−0.0031 (−0.93) |

−0.0066** (−2.02) |

−0.0247*** (−2.76) |

−0.0102** (−2.13) |

−0.0103* (−1.93) |

−0.0172*** (−3.65) |

|

| Relative bid-ask spread (A-share) |

−0.0012 (−0.07) |

−0.0010 (−0.06) |

|||||||

| Relative bid-ask spread (M-share) |

0.0364** (2.24) |

0.0367** (2.25) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (A-share) |

0.0230** (1.97) |

0.0228** (1.96) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (M-share) |

−0.0470*** (−4.70) |

−0.0472*** (−4.71) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

0.7296*** (57.18) |

0.7225*** (54.56) |

0.7296*** (57.18) |

0.7999*** (6.14) |

0.8298*** (6.99) |

0.7233*** (54.65) |

0.7296*** (57.18) |

0.8005*** (6.14) |

0.8310*** (7.02) |

| Observations | 10 298 | 10 298 | 10 298 | 9647 | 9905 | 10 298 | 10 298 | 9647 | 9905 |

| R-Squared | 0.0003 | 0.0030 | 0.0060 | 0.0097 | 0.0461 | 0.0042 | 0.0065 | 0.0101 | 0.0472 |

| Panel B: Hong Kong match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

−0.1095*** (−5.43) |

−0.1035*** (−5.09) |

−0.0966*** (−4.79) |

−0.1053*** (−5.17) |

−0.0898*** (−4.38) |

−0.0874*** (−4.48) |

−0.0908*** (−4.55) |

||

| Post_period*Down_dummy |

−0.0844*** (−5.52) |

−0.0093** (−2.37) |

−0.0089** (−2.56) |

−0.0088* (−1.87) |

−0.0963*** (−5.28) |

−0.0335** (−2.25) |

−0.0255* (−1.81) |

−0.0342** (−2.51) |

|

| Relative bid-ask spread (A-share) |

−0.0253 (−0.54) |

−0.0251 (−0.53) |

|||||||

| Relative bid-ask spread (H-share) |

0.0780** (2.52) |

0.0780** (2.52) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (A-share) |

0.1523*** (4.37) |

0.1517*** (4.34) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (H-share) |

0.0534 (1.40) |

0.0536 (1.40) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

0.6377*** (16.19) |

0.6092*** (15.68) |

0.6377*** (16.19) |

1.0010*** (2.98) |

1.3124*** (5.02) |

0.6106*** (15.27) |

0.6377*** (16.19) |

1.0008*** (2.98) |

1.3133*** (5.04) |

| Observations | 2878 | 2878 | 2878 | 2828 | 2878 | 2878 | 2878 | 2828 | 2878 |

| R-Squared | 0.0551 | 0.0287 | 0.0553 | 0.1653 | 0.1126 | 0.0358 | 0.0577 | 0.1666 | 0.1151 |

- Panel A (B) reports the results of fixed-effects panel regressions for the 89 (26) pilot and M (H) matched stocks. The dependent variable is Value_Ratio, which is computed for each stock as pilot stock value/(pilot stock value + matched stock value). The sample period is from 1 October 2009 to 30 June 2010. Post_period is a dummy variable that is equal to one for the period from 31 March 2010 to 30 June 2010 and zero otherwise. Post_period*Down_dummy is an interaction dummy variable set to one, when the return of A-share market (MKTA) in Models 1 and individual pilot A-share (RETA) in Models 2 is less than 0 during the postperiod and zero otherwise.

- The t-value is adjusted by the Rogers standard error clustered by firm. *, ** and *** indicate significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level, respectively.

We also estimate the regression model using individual stock returns rather than market returns to form a dummy variable for declining returns. These results, which are reported in the last four columns of Panels A and B in Table 4, are qualitatively similar to those reported for the A-share index market return. Again, the evidence is inconsistent with hypothesis 2, with the coefficient on the postperiod dummy and the interaction term being significantly negative in Model (2)B, (2)C, (2)D and (2)E in Panels A and B of Table 4, respectively. This suggests that when the A-share price of an individual stock goes down, there is a decline of A-share trading value relative to the M-share (H-share) trading value. Finally, the coefficients of the relative volatility and relative spread in Model (2)D and (2)E are similar to those in Model (1)D and (1)E in Table 4.

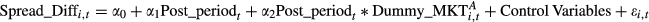

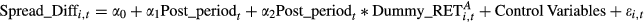

5.3.3 Relative bid-ask spread differential

We test hypothesis 3 that the A-M (A-H) relative spread differential Spread_Diffi,t is lower for those A-shares allowed for margin trading and short selling than for those ineligible in China, that is, matched M-shares and shortable H-shares in Hong Kong. We estimate regression models similar to Equations (6a) and (6b), except that the dependent variable here is Spread_Diffi,t.

The results presented in Panels A and B of Table 5 are inconsistent with our hypothesis 3 of a decline in the A-M (A-H) spread differential following the change in regulation. The A-H results (Panel B) show a clear pattern of an increase in relative spreads following the change in regulation. This is evident in Models (1)A, (1)C, (1)D, (1)E, (2)D and (2)E. The postperiod dummy variable is not consistently statistically significant in the M matching results (Panel A), but when it is statistically significant, it is positive (see Models (1)C, (1)E and (2)E). However, the interaction dummy variable representing the incremental impact of down periods in the postperiod is sometime positive in Panel B, which is difficult to explain. Overall, we conclude there is evidence that spreads increase rather than decrease following the change in regulation.

| SSE A-shares index | Individual A-share | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1)A | (1)B | (1)C | (1)D | (1)E | (2)B | (2)C | (2)D | (2)E | |

| Panel A: China match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

0.0164 (0.68) |

0.0422* (1.64) |

−0.0211 (−0.59) |

0.0895*** (2.82) |

0.0152 (0.57) |

−0.0373 (−1.04) |

0.0621* (1.92) |

||

| Post_period*Down_dummy |

−0.0128 (−0.70) |

−0.0428*** (−3.20) |

−0.0444*** (−3.07) |

−0.0357** (−2.54) |

0.0126 (0.66) |

0.0021 (0.12) |

−0.0185 (−1.06) |

0.0110 (0.58) |

|

| log (Price) A-share |

−0.3443*** (−5.48) |

−0.3442*** (−5.46) |

|||||||

| log (Price) M-share |

0.0810 (1.07) |

0.0817 (1.08) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) A-share |

0.0060 (0.15) |

0.0063 (0.16) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) M-share |

0.1055** (2.45) |

0.1061** (2.46) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (A-share) |

0.0264 (0.78) |

0.0256 (0.76) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (M-share) |

0.0539 (0.68) |

−0.0535 (0.67) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

−0.1087** (−2.41) |

−0.0964* (−2.16) |

−0.1087** (−2.41) |

0.8846 (1.47) |

−1.1210* (−1.78) |

−0.1040** (−2.30) |

−0.1087** (−2.41) |

0.8785 (1.46) |

−1.1294* (−1.79) |

| Observations | 9290 | 9290 | 9290 | 9290 | 9290 | 9290 | 9290 | 9290 | 9290 |

| R-Squared | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0006 | 0.1318 | 0.0239 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.1314 | 0.0236 |

| Panel B: Hong Kong Match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

0.1382*** (3.07) |

0.1287** (2.32) |

0.1514*** (3.17) |

0.1358*** (2.90) |

0.1048 (1.52) |

0.1443** (2.74) |

0.1238** (2.29) |

||

| Post_period*Down_dummy |

0.1080*** (3.70) |

0.0149 (0.53) |

0.0280 (0.97) |

0.0038 (0.14) |

0.1301*** (3.18) |

0.0570 (0.85) |

0.0436 (0.90) |

0.0245 (0.45) |

|

| log (Price) A-share |

−0.5141*** (−5.40) |

−0.5130*** (−5.41) |

|||||||

| log (Price) H-share |

−0.3199*** (−3.60) |

−0.3197*** (−3.59) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) A-share |

0.2223*** (3.44) |

0.2233*** (3.44) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) H-share |

0.2404*** (4.82) |

0.2404*** (4.83) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (A-share) |

−0.2082*** (−3.32) |

−0.2076*** (−3.33) |

|||||||

| Relative price volatility (H-share) |

−0.3095*** (−6.74) |

−0.3095*** (−6.75) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

−0.8722*** (−6.92) |

−0.8367*** (−6.63) |

−0.8722*** (−6.92) |

−2.6842*** (−2.83) |

−3.7128*** (−5.29) |

−0.8405*** (−6.55) |

−0.8722*** (−6.92) |

−2.6958*** (−2.84) |

−3.7132*** (−5.29) |

| Observations | 2829 | 2829 | 2829 | 2828 | 2829 | 2829 | 2829 | 2828 | 2829 |

| R-Squared | 0.0064 | 0.0034 | 0.0064 | 0.4211 | 0.3954 | 0.0047 | 0.0069 | 0.4213 | 0.3955 |

- Panel A (B) reports the results of fixed-effects panel regressions for the 89 (26) pilot and M (H) matched stocks. The dependent variable is Spread_Diff, which is calculated for each stock as log[pilot stock (Ask – Bid)/((Ask + Bid)/2)] – log[matched stock (Ask – Bid)/((Ask + Bid)/2)]. The sample period is from 1 October 2009 to 30 June 2010. Post_period is a dummy variable that is equal to one for the period from 31 March 2010 to 30 June 2010 and zero otherwise. Post_period*Down_dummy is an interaction dummy variable set to one, when the return of A-share market (MKTA) in Models 1 and individual pilot A-share (RETA) in Models 2 is less than 0 during the postperiod and zero otherwise.

- The t-value is adjusted by the Rogers standard error clustered by firm. *, ** and *** indicate significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level, respectively.

Although the results are inconsistent with the recent literature on short-sale bans during the global financial crisis, our evidence is consistent with our trading activity results. An increase in the ability of informed traders to extract higher returns from margin trading and short selling appears to lead to greater asymmetric information risk which is consistent with wider bid-ask spreads in the 89 pilot stocks. The decrease in liquidity could also be expected to flow directly into wider bid-ask spreads.

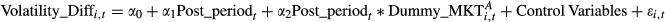

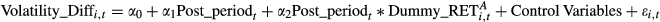

5.3.4 Relative volatility differential

We test hypothesis 4 that there is no clear trend in the A-M (A-H) relative volatility differential Volatility_Diffi,t after the regulation is introduced. In the hypothesis development section, we do not form a view on the direction of the relative volatility differential due to the mixed empirical findings in different settings. However, our univariate analysis presented in Table 1 shows a general decline in relative volatility, albeit only significantly so for the A-M match. In addition, the Appendix III results using 6-month pre- and postperiods show that pilot firm volatility significantly declines relative to both matches.

We estimate regression models similar to Equations (6a) and (6b), except that the dependent variable here is Volatility_Diffi,t. The results are presented in Panels A and B of Table 6. The key variables of interest are the postperiod dummy and the downmarket interaction term. We find a decrease in the volatility of A-shares relative to their M-share counterparts in the postperiod, yet an increase in A-share volatility relative to their H-peers in the postregulation period (in downmarkets). For the A-M volatility differential, we find that the coefficient on both the postperiod and the downmarket interaction term is significantly negative in Model (1)A, (1)B and (2)B of Panel A. This means that when the A-share market (or individual A-share return) goes down, there is a decline of A-share high/low volatility relative to M-share in the postperiod.

| SSE A-shares index | Individual A-share | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1)A | (1)B | (1)C | (1)D | (1)E | (2)B | (2)C | (2)D | (2)E | |

| Panel A: China match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

−0.0553** (−2.49) |

−0.0586** (−2.49) |

−0.0286 (−1.15) |

−0.0926*** (−3.74) |

−0.0502* (−1.89) |

−0.0236 (−0.86) |

−0.0843*** (−3.15) |

||

| Post_period*Down_dummy |

−0.0367** (−2.13) |

0.0054 (0.45) |

0.0093 (0.78) |

−0.0016 (−0.13) |

−0.0442*** (−2.99) |

0.0091 (−0.60) |

0.0009 (0.06) |

−0.0165 (−1.06) |

|

| log (Price) A-share |

0.1145** (2.40) |

0.1144** (2.39) |

|||||||

| log (Price) M-share |

−0.0596 (−1.11) |

−0.0600 (−1.11) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) A-share |

0.0244 (1.12) |

0.0243 (1.11) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) M-share |

−0.0785*** (−3.26) |

−0.0787*** (−3.27) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

−0.0721*** (−3.01) |

−0.0887*** (−3.74) |

−0.0721*** (−3.01) |

−0.6455** (−2.30) |

0.8160** (2.47) |

−0.0872*** (−3.50) |

−0.0721*** (−3.01) |

−0.6437** (−2.28) |

0.8188** (2.48) |

| Observations | 10 283 | 10 283 | 10 283 | 10 283 | 10 283 | 10 283 | 10 283 | 10 283 | 10 283 |

| R-Squared | 0.0030 | 0.0011 | 0.0030 | 0.0217 | 0.0229 | 0.0015 | 0.0030 | 0.0216 | 0.0231 |

| Panel B: Hong Kong match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

−0.0272 (−0.68) |

−0.0622 (−1.50) |

0.0601 (1.32) |

−0.0609 (−1.49) |

−0.0083 (−0.21) |

0.1026** (2.45) |

−0.0077 (−0.20) |

||

| Post_period*Down_dummy |

0.0099 (0.29) |

0.0550** (2.23) |

0.0704*** (3.14) |

0.0553** (2.24) |

−0.0381 (1.17) |

−0.0324 (−1.46) |

0.0028 (0.14) |

−0.0308 (−1.42) |

|

| log (Price) A-share |

0.2132*** (4.38) |

0.2123*** (4.36) |

|||||||

| log (Price) H-share |

0.0344 (0.83) |

0.0340 (0.82) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) A-share |

0.2092*** (5.84) |

0.2082*** (5.43) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) H-share |

0.0062 (0.25) |

0.0061 (0.24) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

0.0316 (0.90) |

0.0145 (0.44) |

0.0316 (0.90) |

−2.7585*** (−5.40) |

−0.1109 (−0.36) |

0.0291 (0.88) |

0.0316 (0.90) |

−2.7456*** (−5.35) |

−0.1083 (−0.35) |

| Observations | 2876 | 2876 | 2876 | 2876 | 2876 | 2876 | 2876 | 2876 | 2876 |

| R-Squared | 0.0007 | 0.0001 | 0.0021 | 0.0983 | 0.0047 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | 0.0961 | 0.0037 |

- Panel A (B) reports the results of fixed-effects panel regressions for the 89 (26) pilot and M (H) matched stocks. The dependent variable is Volatility_Diff, which is calculated for each stock as log[pilot stock (High – Low)/((High + Low)/2)] - log[matched stock (High – Low)/((High + Low)/2)]. The sample period is from 1 October 2009 to 30 June 2010. Post_period is a dummy variable that is equal to one for the period from 31 March 2010 to 30 June 2010 and zero otherwise. Post_period*Down_dummy is an interaction dummy variable set to one, when the return of A-share market (MKTA) in Models 1 and individual pilot A-share (RETA) in Models 2 is less than 0 during the postperiod and zero otherwise.

- The t-value is adjusted by the Rogers standard error clustered by firm. *, ** and *** indicate significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level, respectively.

However, the A-H volatility differential becomes significantly positive when the market is down during the postperiod in Model (1)C. Similarly, after inclusion of both the A- and H-share log(price), and log(volume) in Model (1)D and (1)E, the A-H volatility differential remains strongly positive for the interaction term. Hence, our volatility results based on the 3-month pre- and postperiod windows are mixed. For robustness, in Appendix IV, we re-run the volatility regression models using the 6-month pre- and postwindows. The results are much more consistent. For both the A-M and A-H volatility differential, the postperiod and interaction term are significantly negative in Model (1)A, (1)B and 2(B). When both the postperiod and downmarket interaction term are included in Model 1(C) and 2(C), the postperiod dummy is significantly negative in all models, while the interaction term is also significantly negative for Model 1(C) for A-M and Model 2(C) for both matches. Further, after the inclusion of both A- and H-share log(price), and log(volume), the A-H volatility differential for the interaction term is no longer significantly positive for any model.

5.3.5. Results summary

Our results suggest it is the risk rather than the reality of short-sales activity that leads to the prices of pilot programme stocks decreasing on average, relative to their peers, following the regulation change. Liquidity decreases in pilot programme stocks (relative to matched firms), which is also consistent with uninformed investors reducing trading activity due to the heightened risk of being adversely affected by informed traders. This explanation is also in line with the increase in pilot programme stock spreads (compared to peer firms). On balance, the evidence points to a decline in volatility following the regulation. As mentioned earlier, our key results are robust to matching pilot programme stocks with their Hong Kong-listed H-shares and similar firms listed in China. As a final robustness check, we rule out the possibility that there was a systematic change in the relation between Chinese-listed A-shares and their H-share counterparts by looking at A and H stock pairs that were not affected by the regulation change. These results are available from the authors on request.

6. Conclusion

We examine the effect of margin trading and short sales on relative prices, trading value, bid-ask spreads and price volatility. Our results contribute to the literature in several ways. We have an event that includes both margin trading and short selling, which allows us to see the relative effect of each. Further, the introduction of short selling occurred at a time when market regulators across the globe were increasing restrictions around the short-selling activities. Cash-constrained investors with a positive view of stocks could purchase stocks by borrowing against their house and prior to the commencement of pilot programme. Hence, it is unsurprising that our results show that the short selling effect dominates the margin trading effect. After the launch of the pilot programme by Chinese regulators, the prices of A-shares eligible for short selling and margin trading decrease more than those of noneligible M-shares (or matched H-shares). As a result, the A-M (A-H) premium becomes smaller in the postperiod. Thus, the premium results are consistent with the theoretical models of Miller (1977) and Chen et al. (2002) that constraining short sellers causes overvaluation. However, we find actual short-sales activity is very low. In contrast to the theoretical short-selling models, it appears it is investor selling due to the risk of trading against informed investors (short sellers) rather than the actions of short sellers that drive prices lower in China. This result is broadly consistent with the Ausubel (1990) theory.

In contrast to the Chinese regulator's desire for the short-selling and margin trading programme to improve stock liquidity, we find that pilot firms' liquidity decline is significantly larger relative to the matched samples. Pilot firms' average daily trading value drops significantly during the postperiod and is significantly lower compared with both matched samples. In addition, spreads widen for pilot firms' A-shares relative to their matched H-shares after the launch of pilot programme. The results are in contrast with our hypotheses and the broad short-selling and margin trading literature. However, this evidence supports Ausubel's (1990) prediction that uninformed traders will reduce or avoid trading in situations when they expect an increased likelihood of transacting with informed traders. Further, the ability of informed traders to exploit superior private information appears to lead to an increase in bid-ask spreads in the presence of margin trading and short selling for pilot securities. Assuming the deterioration in liquidity is due to heightened risk of trading against an informed investor, then policy-makers could enact regulation to improve investor confidence. For example, policies enforcing insider trading regulation and encouraging continuous disclosure may improve investor confidence.

Finally, while our volatility results are less consistent than those for premium, value and spread, most of the evidence suggests volatility declines. We find that after the pilot programme launch, volatility decreases when firms are matched with M-shares across all periods, while volatility declines versus H-share pairs over 6-month pre- and postperiods.

Notes

Appendix I

The implementation rules, among other requirements, set out the margin requirement for margin trading and short selling. Under the rules, the investors must deposit cash and/or stocks in the margin account with the qualified dealers. The value in the margin account must not be less than 50% of the initial funds and/or stocks borrowed by the investors, and investors are subject to the margin calls made by the brokerage houses.18

Moreover, the criteria stipulate that brokerage firms that are eligible to undertake new business must

- ‘have net assets of at least RMB 5 billion (approx US$720 million) over the previous 6 months

- be rated as A-class

- have a relatively high proportion of self-owned funds in their net capitals and a certain level of self-owned securities

- have a trading and settlement system in place which meets the requirements for trading and settlement with the stock exchanges, and

- have passed the professional assessment by the China Securities Association (CSA)'.

Similarly, the CSRC require the qualified brokerage firms to select their clients (i.e. investors) for margin trading and short-selling operations very carefully based on client's financial status, trading experience and risk preference. Among other requirements, the qualified, investors must have opened the securities accounts with their brokers for more than 18 months, with the value of total assets in their securities accounts of above RMB 500,000 (approx US$72,500) and total financial assets above RMB 1 million (approx US$145,000).

Appendix II

List of sample stocks eligible for margin trading and short selling

| S.No. | China Code | Name | Exchange | Listed in HKG | SS Allowed in HKG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 600000 | Shanghai Pudong Development Bank Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 2 | 600005 | Wuhan Iron and Steel Company Limited | Shanghai | No | No |

| 3 | 600015 | Hua Xia Bank Co., Limited | Shanghai | No | No |

| 4 | 600016 | China Minsheng Banking Corp., Ltd. | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | 600018 | Shanghai International Port (Group) Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 6 | 600019 | Baoshan Iron and Steel Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 7 | 600028 | China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | 600029 | China Southern Airlines Company Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | 600030 | CITIC Securities Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 10 | 600036 | China Merchants Bank Co., Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | 600048 | Poly Real Estate Group Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 12 | 600050 | China United Network Communications Limited | Shanghai | No | No |

| 13 | 600089 | TEBA Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 14 | 600104 | SAIC Motor Corporation Limited | Shanghai | No | No |

| 15 | 600320 | Shanghai Zhenhua Port Machinery Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 16 | 600362 | Jiangxi Copper Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 17 | 600383 | Gemdale Corporation | Shanghai | No | No |

| 18 | 600489 | Zhongjin Gold Corporation, Limited | Shanghai | No | No |

| 19 | 600519 | Kweichow Moutai Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 20 | 600547 | Shandong Gold Mining Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 21 | 600550 | Baoding Tianwei Baobian Electric Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 22 | 600598 | Heilongjiang Agriculture Company Limited | Shanghai | No | No |

| 23 | 600739 | Liaoning Chengda Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 24 | 600795 | GD Power Development Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 25 | 600837 | Haitong Securities Company Limited | Shanghai | No | No |

| 26 | 600900 | China Yangtze Power Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 27 | 601006 | Daqin Railway Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 28 | 601088 | China Shenhua Energy Company Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 29 | 601111 | Air China Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 30 | 601166 | Industrial Bank Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 31 | 601168 | Western Mining Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 32 | 601169 | Bank of Beijing Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 33 | 601186 | China Railway Construction Corporation Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 34 | 601318 | Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China, Ltd. | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 35 | 601328 | Bank of Communications Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 36 | 601390 | China Railway Group Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 37 | 601398 | Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 38 | 601600 | Aluminium Corporation of China Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 39 | 601601 | China Pacific Insurance (Group) Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 40 | 601628 | China Life Insurance Company Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 41 | 601668 | China State Construction Engineering Corporation Limited | Shanghai | Yes | No |

| 42 | 601727 | Shanghai Electric Group Company Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 43 | 601766 | China South Locomotive and Rolling Stock Corporation | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 44 | 601857 | PetroChina Company Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 45 | 601898 | China Coal Energy Company Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 46 | 601899 | Zijin Mining Group Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 47 | 601919 | China COSCO Holdings Company Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 48 | 601939 | China Construction Bank Corporation | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 49 | 601958 | Jinduicheng Molybdenum Co., Ltd. | Shanghai | No | No |

| 50 | 601988 | Bank of China Limited | Shanghai | Yes | Yes |

| 51 | 000001 | Shenzhen Development Bank Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 52 | 000002 | China Vanke Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 53 | 000024 | China Merchants Property Development Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 54 | 000027 | Shenzhen Energy Group Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 55 | 000039 | China International Marine Containers (Group) Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 56 | 000060 | Shenzhen Zhongjin Lingnan Nonfemet Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 57 | 000063 | ZTE Corporation | Shenzhen | Yes | Yes |

| 58 | 000069 | Shenzhen Overseas Chinese Town Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 59 | 000157 | Changsha Zoomlion Heavy Industry Science and Technology Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 60 | 000338 | Weichai Power Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | Yes | Yes |

| 61 | 000402 | Financial Street Holding Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 62 | 000527 | Guangdong Midea Electric Appliances Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 63 | 000538 | Yunnan Baiyao (Group) Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 64 | 000562 | Hong Yuan Securities Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 65 | 000568 | Luzhou Lao Jiao Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 66 | 000623 | Jilin Aodong Medicine Industry Croup Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 67 | 000630 | Tonling Nonferrous Metal Group Stock Co.,Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 68 | 000651 | Gree Electric Appliances, Inc. of Zhuhai | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 69 | 000652 | Tianjin Teda Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 70 | 000709 | Hebei Iron And Steel Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 71 | 000932 | Hunan Valin Steel Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 72 | 000729 | Beijing Yanjing Brewery Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 73 | 000768 | Xi'an Aircraft International Corporation | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 74 | 000783 | Changjiang Securities Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 75 | 000792 | Qinghai Salt Lake Potash Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 76 | 000800 | Faw Car Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 77 | 000825 | Shanxi Taigang Stainless Steel Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 78 | 000839 | Citic Guoan Information Industry Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 79 | 000858 | Wuliangye Yibin Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 80 | 000878 | Yunnan Copper Industry Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 81 | 000895 | Henan Shuanghui Investment and Development Co., Ltd.a | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 82 | 000898 | Angang Steel Company Limited | Shenzhen | Yes | Yes |

| 83 | 000933 | Henan Shen Huo Coal Industry And Electricity Power Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 84 | 000937 | Jizhong Energy Resources Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 85 | 000960 | Yunnan Tin Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 86 | 000983 | Shanxi Xishan Coal And Electricity Power Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 87 | 002007 | Hualan Biological Engineering Inc. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 88 | 002024 | Suning Appliance Co.,Ltd. | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 89 | 002142 | Bank Of Ningbo Co., Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

| 90 | 002202 | Xinjiang Goldwind ScienceandTechnology Co.,Ltd | Shenzhen | No | No |

- a Due to unavailability of data this stock is not included in our sample.

Appendix III

Six-month pre- and postperiod robustness check

This table is identical to Table 1 except that 6-month rather than 3-month pre- and postperiods are used. The preperiod is 1 July 2009 through 31 December 2009, and the postperiod is 31 March 2010 through 30 September 2010. Some firms were removed from the list of A-shares eligible for the pilot short-selling and margin trading programme after the 30 June 2010. This reduces the sample of eligible A-shares that were shortable during the entire 6-month postperiod window to 81 of which 24 have H-shares.

| Mean | Median | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Diff | p-value | Pre | Post | Diff | p-value | |

| Panel A: Affected Sample (N = 81) | ||||||||

| Price_A | 18.7420 | 16.5330 | −2.2089 | 0.0001 | 14.4500 | 12.0500 | −2.4000 | 0.0001 |

| Value_A | 838.5540 | 398.5860 | −439.9680 | 0.0001 | 596.6000 | 293.1967 | −303.4033 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_A | −7.1671 | −7.0169 | 0.1502 | 0.0001 | −7.1963 | −7.0348 | 0.1615 | 0.0001 |

| Volatility_A | −3.2860 | −3.5129 | −0.2270 | 0.0001 | −3.2939 | −3.5088 | −0.2149 | 0.0001 |

| Panel B: Matched Sample (N = 81) | ||||||||

| Price_M | 15.2528 | 14.1425 | −1.1104 | 0.0001 | 13.9700 | 12.0400 | −1.9300 | 0.0001 |

| Value_M | 238.0020 | 155.2420 | −82.7600 | 0.0001 | 176.4467 | 96.0687 | −80.3780 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_M | −7.0506 | −6.9105 | 0.1401 | 0.0001 | −7.1233 | −6.9551 | 0.1682 | 0.0001 |

| Volatility_M | −3.2452 | −3.3682 | −0.1230 | 0.0001 | −3.2476 | −3.3592 | −0.1116 | 0.0001 |

| Panel C: Affected - Matched Sample | ||||||||

| Premium | −0.0199 | −0.1208 | −0.1008 | 0.0001 | 0.0330 | 0.0267 | −0.0062 | 0.0001 |

| Value_Ratio | 0.7496 | 0.7117 | −0.0379 | 0.0001 | 0.7679 | 0.7336 | −0.0343 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_Diff | −0.1084 | −0.1110 | −0.0027 | 0.8226 | −0.0218 | −0.0589 | −0.0371 | 0.7580 |

| Volatility_Diff | −0.0448 | −0.1457 | −0.1008 | 0.0001 | −0.0514 | −0.1425 | −0.0911 | 0.0001 |

| Panel D: Affected Sample – A-shares (N = 24) | ||||||||

| Price_A | 16.3156 | 13.6711 | −2.6444 | 0.0001 | 13.3100 | 9.8650 | −3.4450 | 0.0001 |

| Value_A | 952.1369 | 415.1103 | −537.0270 | 0.0001 | 755.3362 | 300.7570 | −454.5792 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_A | −7.0071 | −6.8218 | 0.1853 | 0.0001 | −7.0695 | −6.7895 | 0.2799 | 0.0001 |

| Volatility_A | −3.3838 | −3.6843 | −0.3005 | 0.0001 | −3.3884 | −3.6843 | −0.2959 | 0.0001 |

| Panel E: Matched Sample – H-shares (N = 24) | ||||||||

| Price_H | 13.2104 | 13.2527 | 0.0423 | 0.8984 | 8.3950 | 7.7200 | −0.6750 | 0.6656 |

| Value_H | 652.7267 | 495.0173 | −157.7090 | 0.0001 | 400.1050 | 278.1061 | −121.9989 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_H | −6.2222 | −6.2305 | −0.0083 | 0.5694 | −6.3579 | −6.3689 | −0.0109 | 0.3321 |

| Volatility_H | −3.5166 | −3.7246 | −0.2079 | 0.0001 | −3.5245 | −3.7289 | −0.2044 | 0.0001 |

| Panel F: Affected - Matched Sample | ||||||||

| Premium | 0.1952 | 0.0352 | −0.1601 | 0.0001 | 0.1527 | −0.0325 | −0.1851 | 0.0001 |

| Value_Ratio | 0.6354 | 0.5205 | −0.1149 | 0.0001 | 0.6811 | 0.5491 | −0.1320 | 0.0001 |

| Spread_Diff | −0.7680 | −0.5793 | 0.1887 | 0.0001 | −0.6278 | −0.4287 | 0.1991 | 0.0001 |

| Volatility_Diff | 0.1274 | 0.0414 | −0.0860 | 0.0001 | 0.1405 | 0.0426 | −0.0979 | 0.0001 |

Appendix IV

Panel regressions of difference in relative volatility robustness check

| SSE A-shares index | Individual A-share | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1)A | (1)B | (1)C | (1)D | (1)E | (2)B | (2)C | (2)D | (2)E | |

| Panel A: China Match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

−0.1014*** (−4.87) |

−0.0910*** (−3.97) |

−0.0269 (−1.05) |

−0.1238*** (−6.09) |

−0.0806*** (−3.56) |

−0.0210 (−0.85) |

−0.1133*** (−5.66) |

||

| Down dummy * Post_period |

−0.0824*** (−5.73) |

−0.0218* (−1.79) |

−0.0131 (−1.12) |

−0.0287** (−2.22) |

−0.0960*** (−6.70) |

−0.0414*** (−3.82) |

−0.0249** (−2.34) |

−0.0485*** (−4.08) |

|

| log (Price) A-share |

0.1907*** (3.46) |

0.1900*** (3.44) |

|||||||

| log (Price) M-share |

−0.0418 (−0.64) |

−0.0422 (−0.65) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) A-share |

0.0614*** (3.31) |

0.0609*** (3.27) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) M-share |

−0.0768*** (−3.41) |

−0.0771*** (−3.42) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

−0.0448** (−2.05) |

−0.0751*** (−3.20) |

−0.0448** (−2.05) |

−1.2104*** (−4.90) |

0.7855** (2.15) |

−0.0708*** (−2.95) |

−0.0448** (−2.05) |

−1.2030*** (−4.84) |

0.7893** (2.15) |

| Observations | 19 234 | 19 234 | 19 234 | 19 234 | 19 234 | 19 234 | 19 234 | 19 234 | 19 234 |

| R-Squared | 0.0099 | 0.0047 | 0.0102 | 0.0504 | 0.0311 | 0.0066 | 0.0108 | 0.0507 | 0.0318 |

| Panel B: Hong Kong Match | |||||||||

| Post_period |

−0.0465* (−1.88) |

−0.0945** (−2.61) |

0.0804* (1.78) |

−0.0902** (−2.66) |

−0.0620* (−1.86) |

0.1049** (2.59) |

−0.0575* (−1.85) |

||

| Post_period*Down dummy |

−0.0860** (−2.55) |

0.0166 (0.88) |

0.0258 (1.40) |

0.0167 (0.89) |

−0.0877*** (−3.29) |

−0.0462** (−2.81) |

−0.0231* (−1.67) |

−0.0463** (−2.77) |

|

| log (Price) A-share |

0.2445*** (5.30) |

0.2438*** (5.31) |

|||||||

| log (Price) H-share |

0.0711 (1.66) |

0.0712 (1.66) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) A-share |

0.2075*** (7.06) |

0.2066*** (7.01) |

|||||||

| log (Volume) H-share |

0.0121 (0.48) |

0.0123 (0.48) |

|||||||

| Intercept |

0.0959*** (2.84) |

0.1274*** (3.54) |

0.1274*** (3.54) |

−2.7656*** (−6.96) |

−0.1608 (−0.47) |

0.1069*** (3.16) |

0.1274*** (3.54) |

−2.7531*** (−6.92) |

−0.1622 (−0.47) |

| Observations | 5501 | 5501 | 5501 | 5501 | 5501 | 5501 | 5501 | 5501 | 5501 |

| R-Squared | 0.0016 | 0.0070 | 0.0072 | 0.1017 | 0.0152 | 0.0057 | 0.0081 | 0.1016 | 0.0161 |