The key role of specific DSM-5 diagnostic criteria in the early development of alcohol use disorder: Findings from the RADAR prospective cohort study

Abstract

Background

Prevention and early intervention of alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a public health priority, yet there are gaps in our understanding of how AUD emerges, which symptoms of AUD come first, and whether there are modifiable risk factors that forecast the development of the disorder. This study investigated potential early-warning-sign symptoms for the development of AUD.

Methods

Data were from the RADAR study, a prospective cohort study of contemporary emerging adults across Australia (n = 565, mean age = 18.9, range = 18–21 at baseline, 48% female). Participants were interviewed five times across a 2.5-year period. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) AUD criteria and diagnoses were assessed by clinical psychologists using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV), modified to cover DSM-5 criteria. Hazard analyses modeled the time from first alcoholic drink to the emergence of any AUD criteria and determined which first-emergent AUD criteria were associated with a faster transition to disorder.

Results

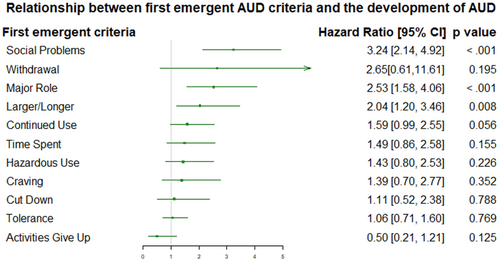

By the final time point, 54.8% of the sample had experienced at least one DSM-5 AUD criterion and 26.1% met criteria for DSM-5 AUD. The median time from first AUD criterion to a diagnosis of AUD was 4 years. Social problems from drinking (hazard ratio [HR] = 3.24, CI95 = 2.14, 4.92, p < 0.001), major role (HR = 2.53, CI95 = 1.58, 4.06, p < 0.001), and drinking larger amounts/for longer than intended (HR = 2.04, CI95 = 1.20, 3.46, p = 0.008) were first-onset criteria associated with a faster transition to AUD.

Conclusion

In the context of a prospective general population cohort study of the temporal development of AUD, alcohol-related social problems, major role problems, and using more or for longer than intended are key risk factors that may be targeted for early intervention.

Graphical Abstract

There are gaps in our understanding of how DSM-5 AUD emerges, which symptoms come first, and whether there are modifiable risk factors that forecast the development of the disorder. The current study analyzed data from a prospective cohort study (N = 565) and found that people experiencing alcohol-related social problems, major role problems, and using more or for longer than intended are at a greater risk for the subsequent development of DSM-5-defined AUD. These symptoms could be targeted in early interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a significant contributor to overall disease burden (World Health Organization, 2010), and is associated with lifelong adverse mental and physical health outcomes (e.g., mental health disorders, illicit drug use, early onset cardiovascular disease, cancers, liver disease, and cognitive impairments) (Bryazka et al., 2022; Schuckit, 2009). Research consistently suggests that emerging adulthood (18–24 years) is a critical period for the onset, development, and entrenchment of AUD (e.g., Teesson et al., 2010). Moreover, although effective treatments exist for AUD, only 5.4% of 18-25 year olds diagnosed with AUD received treatment in the same year as diagnosis (SAMHSA, 2022). As such, understanding important etiological targets for prevention and early intervention is a key public health priority (World Health Organization, 2022). However, few studies have prospectively examined how AUD symptoms initiate and develop over time (Behrendt et al., 2008; Buu et al., 2012), and our understanding of the natural history of AUD symptomology comes primarily from retrospective reports of AUD criteria among people in treatment (Jellinek, 1952; Langenbucher & Chung, 1995; Vaillant & Hiller-Sturmhöfel, 1996). Building effective prevention and early intervention strategies requires fine grained attention to early involvements with alcohol itself, increasing consumption, and early evidence of harmful alcohol-related consequences.

AUD encompasses a range of cognitions and behaviors that have significant impacts on individuals and their communities. The criteria for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) AUD includes continued drinking despite experiencing social and health problems, impaired control over alcohol intake, and the development of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms when stopping alcohol use (American Psychological Association, 2013; Table 1). These criteria are often made up of multiple symptoms, which serve as the basis for clinical assessment and diagnosis, providing a concrete framework for understanding the nature of AUD. To gain deeper insight into the progression of AUD, it is necessary to consider how and when these criteria emerge, and whether there are common or predictable patterns of emergence that underscore the development of AUD. In one study that sought to understand this, Langenbucher and Chung (1995) found that AUD typically emerged across three different stages in treatment-seeking adults. Included in the early stage were criteria such as using alcohol in larger amounts or for longer periods than intended, hazardous use, and alcohol-related social problems. The middle stage criteria included continued alcohol use despite harm, attempts to cut down/quit, tolerance and withdrawal; and the late-stage criteria indicating an accommodation to the disorder (i.e., giving up activities to use alcohol). Studies like these, while valuable, may be limited by Berkson's bias (Berkson, 1946), arising from the highly selective nature of treatment receiving samples. Patterns of criteria emergence in these samples may only reflect those of people with chronic, well-entrenched AUD who received treatment, and not be indicative of the broader population of people who develop AUD (Martin et al., 1996).

| Criteria description | N (%) ever developed in total sample (N = 564) | N (%) of ever developed who developed criterion first | N (%) of those who developed criterion first who went on to develop AUD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | Markedly diminished effect with the use of the same amount of alcohol, or the need to drink markedly more alcohol to achieve intoxication/desired effect | 159 (28.2%) | 128 (80.5%) | 47 (36.7%) |

| Withdrawal | At least two withdrawal symptoms (e.g., malaise, insomnia, psychomotor agitation); and/or taking alcohol to relieve withdrawal symptoms | 15 (2.7%) | 4 (26.7%) | 3 (75.0%) |

| Time spent | Spending a great deal of time obtaining, using or recovering from alcohol use | 69 (12.2%) | 27 (39.1%) | 19 (70.4%) |

| Social problems | The recurrent use of alcohol despite encountering substance-related fights and/or social/interpersonal problems with family, friends and/or close others | 94 (16.7%) | 59 (62.8%) | 50 (84.8%) |

| Major role | The recurrent use of alcohol despite inability to fulfill obligations at school, work, or home | 80 (14.2%) | 35 (43.8%) | 27 (77.1%) |

| Larger/Longer | Drinking alcohol in larger amounts or for longer periods of time than initially intended | 87 (15.4%) | 47 (54.0%) | 33 (70.2%) |

| Hazardous use | The recurrent use of alcohol in physically dangerous situations | 79 (14.0%) | 28 (35.4%) | 17 (60.7%) |

| Continued use | Continued use of alcohol, despite knowing that it is causing a significant problem | 123 (21.8%) | 60 (48.8%) | 34 (56.7%) |

| Cut down | Unsuccessful attempts to reduce or give up alcohol | 47 (8.3%) | 17 (36.2%) | 15 (88.2%) |

| Craving | Serious and persistent craving, desire or need for a substance when sober | 36 (6.4%) | 16 (44.4%) | 12 (75.0%) |

| Activities give up | A marked reduction in engagement in important activities because of substance use | 29 (5.1%) | 11 (37.9%) | 11 (100%) |

One of a handful of studies that have prospectively examined the development of AUD criteria used data from a longitudinal community sample of German adolescents, aged 14–24 at baseline, followed for 10 years (Behrendt et al., 2008, 2013). Behrendt et al. (2008) reported that the typical ages of onset for AUD criteria was between 15 and 21, and the risk of developing DSM-IV alcohol dependence was higher for those who endorsed tolerance to the effects of alcohol, increasing the time spent using alcohol, and drinking for longer or in larger amounts than intended (larger/longer) as their first onset criteria. In another study, Buu et al. (2012) investigated the emergence of first AUD criteria and their associations with the speed of progression to DSM-IV alcohol dependence in an at-risk sample of American adolescents, from ages 10 to 21. Somewhat contrary to Behrendt et al.'s (2008) findings, Buu and colleagues found that participants who experienced recurrent alcohol use despite social problems and tolerance to the effects of alcohol were at higher risk for faster progression to alcohol dependence (Buu et al., 2012). The differences in findings could be attributed to the different methodologies between the studies; for example, while Behrendt et al. (2008) used trained clinician administered structured interviews, Buu et al. (2012) used annual battery assessments not administered by clinicians and examined a high-risk sample. Although these two studies provide valuable information on the emergence of AUD criteria and their associations with subsequent AUD, the large follow-up gaps, and differences in methodology and findings, limit clear conclusions relevant for today's youth, whose drinking behavior and culture has changed significantly in the last few decades (Kraus et al., 2020).

The current study

- What are the common first emergent AUD criteria?

- A. How long after first full drink do AUD criteria tend to emerge?

- Are some first emergent criteria more predictive of developing AUD than others?

- What first emergent criteria predict the time from first full drink to developing AUD?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The RADAR study sample was a cohort of 565 young adult regular drinkers in Australia. To be eligible to participate in RADAR, participants had to report regular alcohol consumption (drinking at least 1–2 days per week), and/or semi-regular binge drinking (drinking four drinks per occasion, two or more times per month). RADAR participants were recruited from an existing, and ongoing, cohort of 1927 adolescents participating in the Australian Parental Supply for Alcohol Longitudinal Study (APSALS; Aiken et al., 2017; Clare et al., 2019; Mattick et al., 2018). Institutional ethics approval was granted for the APSALS by the University of New South Wales Research Ethics Committee and ratified by the universities of Tasmania, Newcastle, Queensland, and Curtin University (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02280551) and RADAR study (UNSW HREC 10144). The APSALS began recruitment in 2010 and participants have been followed up annually for 11 years. The RADAR cohort was recruited between 2016 and 2018 (starting at wave seven of the APSALS), retained 80.4% of participants at the final follow-up, with 66.5% of participants completing all four follow-up interviews (Slade et al., 2021). Those who did not complete any follow-ups neither differ on socio-demographic nor drinking characteristics with those who completed one or more follow-ups (Table S1). Among those who participated in the baseline interview, 48.2% identified as female, with a mean age of 18.9 years (SD = 0.60). Generally, participants' parents had a high level of education, and most of them resided in areas with higher socio-economic advantage. Typically, at baseline interview, RADAR participants consumed alcohol 1–2 days per week, and their usual consumption on a single occasion ranged between 5 and 10 standard drinks (Slade et al., 2021).

Study design and measures

Participants who were eligible and agreed to participate in the RADAR study completed five telephone interviews with trained clinical psychologists at 6-monthly intervals. At each time point, participants were asked about their alcohol consumption, and assessed for individual AUD symptoms using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV). Through algorithms these symptoms combine to form DSM-5 AUD criteria and final diagnosis. The SCID-IV used in the RADAR study was modified by one researcher and author (TC) to allow for diagnosis of DSM-5 and ICD-11 AUD. Detailed description of these modifications, study processes, sample sizing, and measures can be found elsewhere (O'Dean et al., 2022; Slade et al., 2017, 2021). The two previous RADAR studies report on the baseline prevalence and patterns of AUD symptom endorsement (Slade et al., 2021) and on issues specifically around the measurement of tolerance to the effects of alcohol—one of the 11 criteria of AUD (O'Dean et al., 2022). The current paper extends these two papers by tracking change over time in all 11 AUD criteria.

In the clinician administered baseline RADAR interview, participants were asked to report the age at onset for each AUD symptom endorsed. Additionally, each individual AUD symptom was assessed for clinical significance (i.e., occurring with sufficient severity and frequency) by the interviewing clinical psychologist. The assessment of severity and frequency required a judgment of whether the symptom was experienced as persistent (e.g., lasting for more than 1 month), and/or recurrent (e.g., happened on more than three occasions) in the previous 6 months. As the tolerance criterion is over-endorsed in emerging adults due to relatively naïve drinking careers, we applied additional thresholds to satisfy the tolerance criterion (O'Dean et al., 2022). These additional thresholds required an initial quantity of four (for women) or five (for men) standard drinks to feel drunk, and a 50% minimum increase in drinking quantity to feel drunk. This definition of tolerance has been tested on this sample, and is more strongly associated with new onset AUD, and persistent and limited AUD than the definition without thresholds (see O'Dean et al., 2022 for more detail).

Age at onset of first full drink

Age at onset for first full drink was taken from the wave of APSALS at which the participant first reported having consumed a full alcoholic drink (legal purchase age for alcohol in Australia is 18 years old). Participants who reported having already had a full drink under the age of 12 (i.e., in wave 1 of APSALS) were coded as having had their first full drink at 11 years of age (n = 15, 2.7%).

Onset ages of DSM-5 AUD symptoms and diagnoses

The onset age for each DSM-5 AUD criterion was derived from the earliest age at which the constituent symptoms were first reported in the RADAR baseline or follow-up interviews. If a criterion was reported in the RADAR baseline interview, we used the retrospectively reported age at onset as the age at onset for that criterion. If the criterion was not reported at baseline, but was reported in follow-up interviews, we recorded the age at onset for the criterion as the age at the time of the follow-up interview in which the criterion was first endorsed. First emergent criteria were defined as those with the earliest age at onset for each participant. The onset age for DSM-5 AUD diagnosis was derived from the age by which at least two clinically significant AUD criteria had emerged.

Statistical methods

To determine the relative predictive ability of each first emergent criterion for developing AUD we compared the sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) for each first emergent criterion (i.e., the criterion with the earliest age at onset). For the remaining aims of this study, we used the Kaplan–Meier method to estimate duration in years from first full drink to first DSM-5 AUD criterion onset, first criterion onset to AUD, and first full drink to AUD. Next, we used Cox proportional hazards (CPH) regressions to investigate the effects of first emergent criteria on time from first full drink to AUD. We did this in a stepped approach. We first investigated univariable associations between each first emergent criterion and time from first full drink to AUD. We then included all first emergent criteria and adolescent antecedents: externalizing, internalizing, underage risky drinking, peer use, parental binge drinking, and sex (see “Supplementary Information” for further detail) in the same multivariable model to determine which first emergent criteria were uniquely predictive of faster transition from first full drink to AUD when controlling for a selection of the most relevant adolescent antecedents of AUD.

We tested the proportional hazards assumption using Schoenfeld's residuals. If the assumption was violated (p < 0.05), we planned to use the tt (time transform) function in the Survival package, which includes a covariate × time interaction that accounts for the time-dependent nature of the hazard, and improves model fit (Therneau et al., 2022). Analyses were conducted in R Version 4.2.3 (release 2023-03-15). Data were manipulated and variables were coded using the dplyr (v1.0.9; Wickham, 2022a, 2022b), psych (v2.0.8; Revelle, 2021), and tidyr (v1.1.4, Wickham, 2022a, 2022b) packages. Sensitivity and specificity were estimated using the epiR package (Stevenson & Sergeant, 2023). Hazard analyses were conducted using the Survival package (Therneau et al., 2022).

Missing data

We excluded one participant who did not have data recorded in APSALS, and only completed the baseline interview of RADAR (N = 564). Participants who reported their first onset of criteria as earlier than their first reported drink of alcohol were also excluded from relevant analyses (N = 6). Attrition analyses comparing those who completed no follow-up interviews and those who completed one or more are reported in the supplementary materials (Table S1).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

- What are the common first emergent AUD criteria?

- A. How long after first full drink do AUD criteria tend to emerge?

- B. How long after criteria first emerge does AUD tend to develop?

- Are some first emergent criteria more predictive of developing AUD than others?

- Which first emergent criteria predict the time from first full drink to developing AUD?

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | 0.51 (0.43, 0.58) | 0.32 (0.24, 0.40) | 0.41 (0.36, 0.47) |

| Withdrawal | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.02 (0.004, 0.06) | 0.51 (0.49, 0.52) |

| Time spent | 0.95 (0.91, 0.98) | 0.13 (0.08, 0.19) | 0.54 (0.51, 0.57) |

| Social problems | 0.95 (0.90, 0.97) | 0.34 (0.26, 0.42) | 0.64 (0.60, 0.68) |

| Major role | 0.95 (0.91, 0.98) | 0.18 (0.12, 0.25) | 0.57 (0.53, 0.60) |

| Larger/Longer | 0.91 (0.86, 0.95) | 0.22 (0.16, 0.30) | 0.57 (0.53, 0.61) |

| Hazardous use | 0.93 (0.88, 0.97) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.18) | 0.52 (0.49, 0.56) |

| Continued use | 0.84 (0.78, 0.89) | 0.23 (0.16, 0.31) | 0.54 (0.49, 0.58) |

| Cut Down | 0.99 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.10 (0.06, 0.16) | 0.54 (0.52, 0.57) |

| Craving | 0.98 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.08 (0.04, 0.14) | 0.53 (0.50, 0.55) |

| Activities give up | 1.00 (0.98, 1.00) | 0.07 (0.04, 0.13) | 0.54 (0.52, 0.56) |

- Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval.

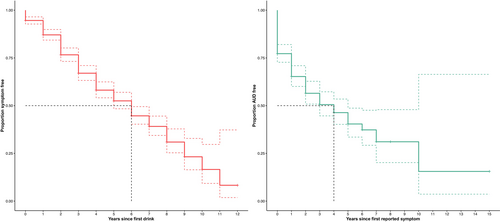

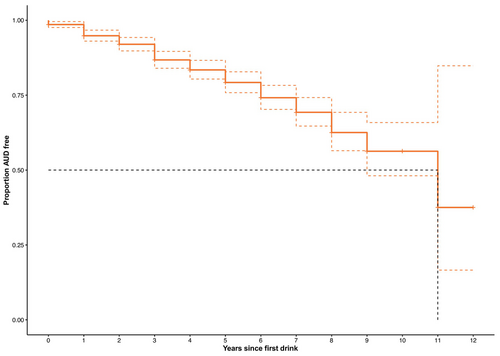

The median time from first full drink to AUD diagnosis in the whole RADAR sample was 11 years (Figure 2). The cumulative time-to-event rate within 1 year of first full drink was 0.95 (CI95 = 0.97, 0.93). This decreased to 0.87 (CI95 = 0.90, 0.84) by 3 years following the first full drink. That is, 13% of participants developed AUD within 3 years of their first full drink.

Univariable regression analyses with each possible first emergent criterion in the models investigated whether developing specific criteria first (compared to other first emergent criteria) increased the risk of developing AUD (Table 3). In these models, five criteria were associated with greater risk of progression from first full drink to AUD, and one (tolerance) was associated with a decreased risk of progression from first full drink to AUD (Table 3).

| Univariable models | Multivariable model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| First emergent criteria | ||||

| Tolerance | 0.57 (0.41, 0.81) | 0.002 | 1.06 (0.71, 1.60) | 0.769 |

| Withdrawal | 1.91 (0.61, 5.99) | 0.270 | 2.65 (0.61, 11.61) | 0.195 |

| Time spent | 1.54 (0.95, 2.51) | 0.081 | 1.49 (0.86, 2.58) | 0.155 |

| Social problems | 3.26 (2.31, 4.60) | <0.001 | 3.24 (2.14, 4.92) | <0.001 |

| Major role | 2.54 (1.67, 3.87) | <0.001 | 2.53 (1.58, 4.06) | <0.001 |

| Larger/Longer | 1.95 (1.32, 2.88) | 0.001 | 2.04 (1.20, 3.46) | 0.008 |

| Hazardous use | 1.30 (0.78, 2.15) | 0.312 | 1.43 (0.80, 2.53) | 0.226 |

| Continued use | 1.39 (0.94, 2.05) | 0.095 | 1.59 (0.99, 2.55) | 0.056 |

| Cut down | 2.22 (1.29, 3.81) | 0.004 | 1.11 (0.52, 2.38) | 0.788 |

| Craving | 1.52 (0.84, 2.77) | 0.169 | 1.39 (0.70, 2.77) | 0.352 |

| Activities give up | 2.67 (1.42, 5.02) | 0.002 | 0.50 (0.21, 1.21) | 0.125 |

- Note: Significant findings in bold. Multivariable model adjusts for all first emergent symptoms, plus sex and select important adolescent antecedents for heavy drinking and AUD (i.e., externalizing, internalizing, parental binge drinking, underage peer drinking, and underage risky drinking).

- Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; CI, confidence interval.

The multivariable model included all possible first emergent criteria and controlled for relevant antecedent risk factors for alcohol use and alcohol use disorder. When all variables were accounted for in the one model, social problems (HR = 3.24, CI95 = 2.14, 4.92, p < 0.001), major role (HR = 2.53, CI95 = 1.58, 4.06, p < 0.001), and drinking larger amounts/for longer than intended (HR = 2.04, CI95 = 1.20, 3.46, p = 0.008) as first emergent criteria were uniquely associated with a risk of progression from first full drink to AUD (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the emergence of specific DSM-5 AUD criteria and their relationships to the development of an AUD diagnosis, within the context of a regular drinking general population sample recruited during adolescence. The median time from first full drink to the development of AUD criteria was 6 years and the median time from first criterion to AUD was 4 years. When looking at first onset criteria as risk factors for the speed of transition from first full drink to AUD, three criteria emerged as being associated with faster transitions: alcohol-related social problems, major role (i.e., home, family, employment, and/or education) problems from drinking, and drinking for longer or in larger amounts than intended.

Risk factors for speedier transition to AUD

These findings have important implications for understanding the early stages of AUD in emerging adults. The strong association between alcohol-related social problems and progression to AUD suggests that interpersonal difficulties (e.g., conflicts with friends, family, and/or partners) may be particularly important on the pathway to AUD. This finding is consistent with prior research conducted in both older clinical populations (Langenbucher & Chung, 1995) and at-risk youth populations (Buu et al., 2012). This congruence across different studies reinforces the crucial role that social problems might play in the development of AUD. There are several potential explanations for the observed associations between social problems and a faster transition to AUD. Individuals facing social problems may be more vulnerable to experiencing negative consequences because of alcohol use. For example, they might lack a strong social support network or have strained relationships (Camara et al., 2017). Consequently, alcohol use might exacerbate their existing social issues, leading to a higher likelihood of developing AUD. Additionally, experiencing social problems in young adulthood could trigger maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as excessive drinking (e.g., Pedersen, 2017; Todd et al., 2009). Indeed, studies show that individuals who use alcohol as a coping mechanism are more prone to developing alcohol-related difficulties (Bresin & Mekawi, 2021). Finally, experiencing social and interpersonal problems might be indicative of broader externalizing behavioral issues in young adults. These externalizing behaviors, such as interpersonal aggression and impulsivity, have been linked to alcohol misuse (Meque et al., 2019). Thus, young adults facing social difficulties and displaying externalizing behavioral issues may have an elevated risk of developing AUD (Meque et al., 2019).

Our finding that major role problems were associated with a faster transition to AUD aligns with previous research conducted with a German youth population (Behrendt et al., 2008). The presence of major role problems as a first criteria could indicate a more severe form of AUD or a faster progression to a clinically significant level of alcohol-related impairment. Major role problems refer to issues related to significant areas of functioning, such as work, education, family, or social responsibilities. These problems might manifest as declining job or academic performance, or neglect of important responsibilities. As with social problems above, the association between major role problems and a faster transition to AUD might suggest a cyclical relationship. For example, academic or work-related struggles due to alcohol use may lead to stress and further drinking as a coping mechanism, which can, in turn, worsen the initial problems. This cyclic pattern may accelerate the development of AUD over time.

The observation that consuming alcohol in larger amounts or for longer than intended periods was associated with a faster transition to AUD might indicate early difficulties in self-regulation of alcohol consumption. Self-regulation involves the ability to control one's behaviors, emotions, and impulses in line with long-term goals (Rachlin, 1974). Individuals who struggle with controlling their alcohol intake might exhibit deficits in self-regulatory processes, making it challenging to adhere to the limits they set for themselves. Indeed, experiencing the larger/longer symptom first may be an early indicator of a shift from impulsive to compulsive use, which according to Koob & Volkow's theory is one of the hallmarks of a disordered drinking state (Koob & Volkow, 2010). Moreover, individuals who experience difficulties in limiting their alcohol consumption may be at an increased risk of engaging in heavy or binge drinking, leading to alcohol-related problems and dependency (e.g., Addolorato et al., 2018; King et al., 2016). Using more or for longer than intended might be an early stage in the progression towards impaired control over alcohol consumption.

Clinical significance

Understanding prodromal symptoms and their progression to full disorders is vital for designing early intervention programs (McGorry et al., 2008). Such research helps to target intervention strategies and address disorders before they become entrenched and more difficult to treat (Berk et al., 2017). Research in other areas of mental health has taken steps towards these staging models of illness and have uncovered important prodromal symptoms for development and prognosis of various disorders including psychosis (Fusar-Poli et al., 2014; McGorry et al., 2008), bipolar disorder (Berk et al., 2017), major depressive disorder (Verduijn et al., 2015), and eating disorders (Stice et al., 2021). However, little research has been conducted on AUD criterion emergence and its relation to AUD onset. Although preliminary, our findings hold important implications for understanding the factors that contribute to the development of AUD in young adults and thus target areas for early intervention. Addressing social and self-control problems and providing appropriate interventions for individuals facing these challenges may prove crucial in preventing or slowing down the progression to AUD.

Moreover, the results highlight the importance of early identification, either via screening from health professionals or self-assessment, of social and major role problems and impaired control of alcohol consumption. This is particularly critical, as research suggests that the median time from AUD onset to receiving treatment is 18 years, and those who develop symptoms earlier are less likely to seek treatment (Chapman et al., 2015). By identifying those at higher risk, healthcare professionals can offer targeted interventions, such as counseling or social support programs, to address both social and role issues and potential alcohol-related concerns.

Strengths and limitations

Although this study fills an important gap in the literature, our findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, due to the limitations of our sampling (i.e., APSALS and RADAR participants are more advantaged), our scope for generalizing our findings to all young adults across the socioeconomic spectrum is limited. However, AUD has a peak age at onset at 18–24 years, making this population one of interest (Teesson et al., 2010). Additionally, not all participants in the study developed AUD criteria. This meant that our sample was too small to look at interactions between adolescent antecedent risk factors and first onset symptoms. Moreover, we did not assess poly-substance use or co-occurring psychopathology, which might aid understanding of how problems with self-regulation play a role in the faster transition to AUD. Findings from such analyses could help further elucidate particular risk profiles to target for early intervention for AUD in young adults. Further, 65% of first criterion endorsement came from the baseline interview, meaning that the age of onset for those criteria is retrospectively reported. However, the mean and median ages of symptom onset were 18, as was the mean age at the baseline interview. As such, recall period for most participants was likely short, and comparable to the follow-up interviews. Finally, we recognize the potential loss of information by choosing to model time as yearly increments given the 6-monthly nature of data collection. However, age in years provides a widely understood measure that facilitates comparison across diverse populations and studies, while maintaining consistency with the way age of onset was measured in the baseline interview.

The present study has several notable strengths. We used DSM-5 criteria for assessing AUD criteria, ensuring consistent and clinically rigorous evaluations. Additionally, clinical assessments provided context-sensitive evaluations beyond simple checklist appraisals, though it must be acknowledged that measurement issues in this area are challenging. Short intervals between assessments reduced recall bias and provided a precise understanding of the temporal progression from the first alcoholic drink to criterion emergence. A relatively large sample size allowed for robust conclusions and high retention rates minimized potential attrition biases. Analyzing different starting points (first full drink, first criteria) and milestones (onset of criteria, AUD) offered insights into the stages of alcohol involvement and factors influencing transitions.

CONCLUSION

This study investigated first onset criterion predictors of the developmental course of AUD among young adults. The median time from the first full drink to the development of AUD criteria was 6 years and the median time from the first symptom to AUD was 4 years. Notably, three criteria—alcohol-related social problems, major role problems, and using more or for longer than intended—emerged as risk factors associated with faster transitions from the first full drink to AUD, even after controlling for antecedent risk factors. The findings highlight the importance of early criteria recognition for understanding the early stages of AUD. Further research is needed to replicate the results in larger samples and explore specific risk profiles for targeted early intervention in AUD among young adults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the APSALS and RADAR participants for their contribution to this project, the schools who assisted with recruitment of the cohort. We would also like to thank Dr Amy Peacock, Professor Jackob Najman, Professor Louisa Degenhardt, Dr Monika Wadolowski, Professor John Horwood, Ms Clara De Torres, and Dr Laura Vogl for their work in the conceptualization, development, and maintenance of the cohort. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley - The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1105521). KK's contribution was funded by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (APP1041867). The APSALS study was funded by a 2010–2014 Australian Research Council Discovery Project Grant (DP:1096668), two Australian Rotary Health Grants and a National Health and Medical Research Council project grant (APP1146634).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.