Emergency department utilization by youth before and after firearm injury

Presented at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, Phoenix, AZ, (May 2024) and awarded the Fellow Award for Best Abstract and Presentation and the Pediatric Trainee Abstract Award. Also presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting, Toronto, Ontario, (May 2024).

Supervising Editor: Mark R. Zonfrillo

Abstract

Background

Emergency department (ED) visits may serve as opportunities for firearm injury prevention and intervention efforts. Our objective was to determine ED utilization by youth before and after firearm injury.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of ED encounters by youth (0–18 years old) with firearm injury from eight states using the 2019 State ED and Inpatient Databases. Our primary outcome was an ED encounter (1) 90 days before or (2) 90 days after index injury. We used generalized estimating equations, accounting for hospital clustering, to determine associations between ED utilization and ED type (pediatric vs. general), youth age, sex, race and ethnicity, urbanicity, and insurance status.

Results

We identified 1035 ED encounters for firearm injury (median [IQR] age 17 (15–18) years, 85.3% male, 63.3% non-Hispanic Black, 68.6% publicly insured, 90.5% living in a metropolitan area, 52.8% general ED). In the 90 days before an index injury, 12.8% of youth had an ED encounter; of these, 68.2% occurred in general EDs, and 18.2% were for trauma. In the 90 days after an index injury, 22.1% of youth had an ED encounter; of these, 50.0% occurred in general EDs, and 22.6% were for trauma. We found no significant association between ED type and ED utilization patterns. Few youths changed ED type across longitudinal encounters.

Conclusions

Youth have high rates of ED utilization before and after firearm injury. Half of firearm-injured youth receive their emergency care exclusively in general EDs. Implementing firearm injury prevention and intervention efforts in all ED settings is critical.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Firearms are the leading cause of death among youth in the United States.1 Nonfatal morbidities also have devastating impacts on youth, their families, their communities, and the health care system that cares for them.2-5 Firearm injuries are associated with physical and mental sequelae among youth including subsequent violent injuries, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse.6-10 These youth are also more likely to have increased health care utilization after their injury, including ED visits, hospitalizations, and health care expenditures.5, 11, 12 Given the worsening firearm violence epidemic among youth in the United States,13 there is an urgent need to identify opportunities to implement effective prevention and intervention strategies in various settings.

Importance

Prior studies have demonstrated efficacy in emergency department (ED)-based interventions for youth with injury-related risk behaviors.7, 14-17 However, these studies have often been located in pediatric EDs, while most childhood ED visits occur in general EDs.18, 19 At this time, it is unclear whether these same patterns of ED utilization exist for firearm-injured youth including in the period of time leading up to and immediately following their injury. Prior work exploring location of ED visits for pediatric firearm injury have examined hospital trauma–level status or teaching status with limited information on general pediatric capabilities at the presenting hospital.20, 21 To appropriately situate interventions to prevent injury and improve holistic outcomes in firearm-injured youth, it is important to determine patterns of ED utilization in the period before and after firearm injury to understand if and where there are opportunities for prevention and intervention efforts in the ED setting. Additionally, differences in presentations by ED site-level (e.g., pediatric vs. general ED) and patient-level characteristics warrant investigation, as differential resource availability may impact ED utilization and downstream outcomes across population subgroups.

Goals of this investigation

The objective of this study was to determine ED utilization patterns before and after ED visits by youth for firearm injury, including ED site-level and patient-level characteristics. This hypothesis-generating work on health service utilization by firearm-injured youth is executed with the goal of informing future ED-based interventions.

METHODS

Study design and setting

We performed a retrospective cohort study using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State ED and Inpatient Databases (SEDD/SID) of Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Maryland, Nebraska, New York, Vermont, and Wisconsin from 2019.22 The SEDD/SID databases provide patient-level data related to health care utilization capturing ED encounters at hospital-owned EDs. Patient identifiers allow longitudinal follow-up of patients within a given state including across different hospital systems, and states were chosen due to accuracy of the visit link variable. SEDD/SID data were linked using the HCUP-provided hospital identifier to the National Emergency Department Inventory (NEDI-USA) data set to identify trauma center status.23, 24 We followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting of cross-sectional studies.25 This study was determined exempt by the senior author's institutional review board. The funders had no role in the conduct or reporting of this study.

Study population

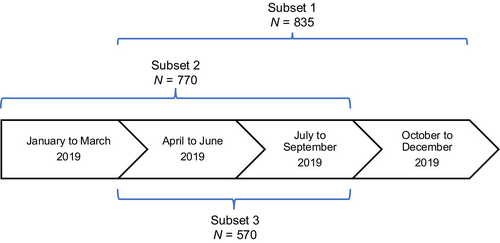

We included all ED encounters for youth (0–18 years of age) with an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code for fatal and nonfatal firearm injury, inclusive of all intents, limited to those with an “initial encounter” qualifier. Consistent with prior literature, we excluded all nonpowder firearm mechanisms (i.e., air guns, BB guns, flare guns).26 The index encounter was considered the first ED encounter for firearm injury for each patient within each state during the study period; patients with recurrent firearm injury during the study period were only included at the time of index injury. Three overlapping cohort subsets were defined based on the time of index injury to permit uniform lookback and follow-up durations (Figure 1). Subset 1 included patients with the opportunity to have an ED encounter in any of the 90 days before their index injury (i.e., patients with an index injury from April to December); Subset 2 was defined as patients with the opportunity to have an ED encounter in any of the 90 days after their index injury (i.e., index injury from January to September); Subset 3 was defined as patients with the opportunity to have an ED encounter in the 90 days before and/or after their index injury (i.e., index injury from April to September). Given the overlapping nature of these subsets, patients may be represented in more than one subset (Figure 1).

Measures

Patient age was categorized as 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, and 15–18 years.11 Sex was categorized as male or female. Mutually exclusive race and ethnicity categories were determined using the HCUP “RACE” variable,27 a uniform coding for race and ethnicity, as follows: Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and other. “Other” encompassed categories representing <5% of the study sample: “Asian or Pacific Islander,” “Native American,” and “other.” Recognizing that race and ethnicity are social and not biological constructs, we included this variable as a proxy for the influence of structural racism on health care utilization, which may contribute to health care disparities.28 Insurance status was categorized as private, public, or other (including self-pay, no charge, other, and missing data). Urbanicity of patient residence was determined using the 2013 Urban Influence Codes (UIC)29 and stratified as metropolitan (UIC 1–2) and nonmetropolitan (UIC 3–12).

We defined the type of ED for each encounter based on pediatric resources available at the hospital. A pediatric ED was defined as an ED located within (1) a freestanding children's hospital or (2) a hospital that did not meet qualification for a freestanding children's hospital but had a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).30, 31 A freestanding children's hospital was defined as ≥70% visits by children and/or admissions restricted to children.32 Presence of a PICU was determined by >25 admissions per year with critical care charges. All other EDs were considered general EDs (for full details regarding these methods, please see the supplemental material accompanying the online article). Urbanicity of the ED was determined using the same classification system as urbanicity of youth residence and categorized as metropolitan or nonmetropolitan. We classified whether the initial ED at index injury was affiliated with a trauma center, including pediatric trauma centers. The annual ED volume (total visits) was determined by the annual visit volume in our sample year and categorized as small (<30,000 visits), medium (30,000–59,999 visits), and large (≥60,000 visits).33 Annual ED volume of visits by children was determined by the number of ED visits by children in our sample year and categorized as low (<1,800 visits), medium (1,800–4,999 visits), medium-high (5,000–9,999 visits), and high (≥10,000 visits).34 We described disposition from the ED including whether a patient was admitted, discharged, transferred to another ED (including whether transfer was from a general to pediatric ED), or had in-hospital mortality (including mortality in ED or inpatient). We determined proportion of visits for “trauma” using the ICD-based diagnosis grouping system for pediatric ED visits.35

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were having an ED encounter in (a) the 90 days before or (b) the 90 days after the index injury.

Data analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics to summarize youth and encounter characteristics at time of the index injury and the characteristics of encounters before (Subset 1) and after (Subset 2) the index injury. We used generalized estimating equations with a binomial distribution, logit link, working independence correlation structure, and robust standard errors, to examine associations of youth characteristics (age, sex, race and ethnicity, urbanicity of youth residence, insurance status) and ED type at index injury with ED utilization outcomes, adjusting for hospital clustering. We assessed two primary outcomes in separate models: (1) any ED visit in the 90 days before index injury (Subset 1) and (2) any ED visit in the 90 days after the index injury (Subset 2). Youth who died at the index visit were excluded from the analysis of ED visits after injury. We conducted a sensitivity analysis repeating the above models in Subset 3. Finally, we constructed a Sankey diagram to illustrate ED utilization before, during, and after the index injury in Subset 3. There were minimal missing data in this data set; for variables where ≥5% of the sample had missing data (i.e., race and ethnicity), missing data were coded as a category. Otherwise, available case analysis was used to handle missing data. Analyses were performed using Stata SE 15.1 (StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study sample

We identified 1035 ED encounters by youth for firearm injury in 2019 (Table 1). These encounters were predominantly among adolescents (median [IQR] age 17 [15–18] years), males (85.3%), and non-Hispanic Black youth (63.3%) with modest proportions of non-Hispanic White youth (19.4%) and few Hispanic youth (7.1%) and youth with other races and ethnicities (5.0%). Most youth resided in a metropolitan area (90.5%). Qualitatively similar sample characteristics were found in each cohort subset (Table S1).

| Characteristic of index ED encounter | Index ED encounters for firearm injury (N = 1035) |

|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |

| 0–4 | 26 (2.5) |

| 5–9 | 34 (3.3) |

| 10–14 | 117 (11.3) |

| 15–18 | 858 (82.9) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 152 (14.7) |

| Male | 883 (85.3) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 74 (7.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 655 (63.3) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 201 (19.4) |

| Othera | 52 (5.0) |

| Missing | 53 (5.1) |

| Urbanicity of youth residence | |

| Metropolitan | 937 (90.5) |

| Nonmetropolitan | 95 (9.2) |

| Insurance status | |

| Private | 191 (18.5) |

| Public | 710 (68.6) |

| Otherb | 134 (12.9) |

| ED type at initial presentation for index injuryc | |

| Pediatric | 489 (47.2) |

| General | 546 (52.8) |

| Urbanicity of ED | |

| Metropolitan | 959 (92.7) |

| Nonmetropolitan | 76 (7.3) |

| Trauma center affiliation of ED | |

| Any trauma center affiliation | 712 (68.8) |

| Pediatric trauma center affiliation | 188 (18.2) |

| Annual ED volume (total visits) | |

| Small (<30,000) | 100 (9.7) |

| Medium (30,000–59,999) | 271 (26.2) |

| Large (≥60,000) | 663 (64.2) |

| Annual ED volume (visits by children) | |

| Low (<1,800) | 58 (5.6) |

| Medium (1,800–4,999) | 130 (12.6) |

| Medium-high (5,000–9, 999) | 220 (21.3) |

| High (≥10,000) | 589 (56.9) |

| ED disposition | |

| Admit | 351 (33.9) |

| Discharge (to home or nonacute care) | 614 (59.3) |

| In-hospital mortality | 70 (6.8) |

| Transfer to acute care | 61 (5.9) |

| Transfer from general to pediatric EDc | 37 (3.6) |

- Note: Data are reported as n (%).

- a Other race and ethnicity includes Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, and other.

- b Other insurance status includes self-pay, no charge, other, and missing.

- c Pediatric ED defined as ED located within a freestanding children's hospital or hospital with a pediatric intensive care unit; all other EDs categorized as general.

ED encounters for index injury

Fifty-three percent of index encounters by youth for firearm injury were at general EDs (Table 1). Over two-thirds of youth (68.8%) presented to an ED with a trauma center affiliation and 18.2% presented to an ED with a pediatric trauma center affiliation. Most youth were cared for in an urban ED (92.7%) in the highest annual volume category (≥60,000 visits overall; 64.2%). Slightly fewer youth (56.9%) received care in an ED with the highest pediatric annual volume (≥10,000 annual visits by children). Six percent of youth were transferred, and few (3.6%) were transferred from a general ED to a pediatric ED for their index injury. Approximately one-third of youth (33.9%) had a final disposition of inpatient admission (inclusive of initial and transfer institutions). Seven percent of youth died during their index ED visit or during that hospital admission.

ED encounters before index injury (Subset 1)

In the 90 days before an ED visit for firearm injury, 12.8% of youth had an ED encounter (n = 107). These encounters were typically at general EDs (68.2%). Among these encounters, 18.2% of encounters were for trauma. The adjusted odds of having an ED encounter in the 90 days before index presentation for firearm injury was higher among female youth (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.11, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.19–3.74) compared to male youth and lower among youth with other race and ethnicity (aOR 0.10, 95% CI 0.01–0.84) or missing race and ethnicity (aOR 0.16, 95% CI 0.05–0.55) compared to non-Hispanic White youth (Table 2).

| Characteristic of index ED encounter | ED encounter in 90 days before injury (n = 833) | ED encounter in 90 days after injury (n = 718) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| 0–4 | 1.69 (0.62–4.60) | 0.67 (0.21–2.17) |

| 5–9 | 0.16 (0.02–1.34) | 0.49 (0.16–1.50) |

| 10–14 | 0.43 (0.17–1.10) | 0.62 (0.34–1.13) |

| 15–18 | Referent | Referent |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Referent | Referent |

| Female | 2.11 (1.19–3.74) | 1.64 (1.00–2.68) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 0.67 (0.28–1.62) | 0.60 (0.24–1.46) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.61 (0.34–1.10) | 1.27 (0.72–2.27) |

| Non-Hispanic White | Referent | Referent |

| Other | 0.10 (0.01–0.84) | 0.62 (0.21–1.82) |

| Missing | 0.16 (0.05–0.55) | 1.48 (0.53–4.11) |

| Urbanicity of youth residence | ||

| Metropolitan | Referent | Referent |

| Nonmetropolitan | 0.56 (0.21–1.48) | 0.86 (0.42–1.76) |

| Insurance status | ||

| Private | Referent | Referent |

| Public | 1.39 (0.75–2.59) | 1.13 (0.68–1.90) |

| Other | 0.49 (0.16–1.45) | 0.80 (0.36–1.77) |

| ED type at initial presentation for index injury | ||

| General | Referent | Referent |

| Pediatric | 0.99 (0.64–1.52) | 1.06 (0.72–1.55) |

ED encounter after index injury (Subset 2)

In the 90 days after an ED visit for firearm injury, 22.1% of youth had an ED encounter (n = 170). Half of these encounters (50.0%) occurred at general EDs. Among these encounters, 22.6% of encounters were for trauma. The adjusted odds of having an ED encounter in the 90 days after index presentation for firearm injury was higher among female youth compared to male youth (aOR 1.64, 95% CI 1.00–2.68; Table 2).

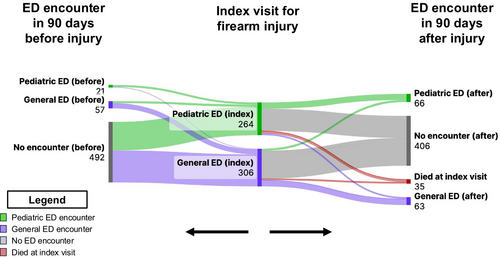

Longitudinal care (Subset 3)

Few youths changed ED type across longitudinal encounters (Figure 2). In the 90 days before an ED visit for firearm injury, 3.7% of youth were seen in a different type of ED than the ED for their index injury (i.e., pediatric ED in prior visit then general ED for index injury visit or general ED in prior visit then pediatric ED for index injury visit). In the 90 days after an ED visit for firearm injury, 4.2% of youth were seen in a different type of ED than the ED for their index injury.

Sensitivity analysis (Subset 3)

In our sensitivity analysis, we found that youth ages 10–14 years had decreased adjusted odds of having an ED encounter before their injury and female youth had increased adjusted odds of having an ED encounter before their injury (Table S2).

DISCUSSION

Almost a quarter of firearm-injured youth revisited the ED within 90 days of their index firearm injury and almost a quarter of these return visits were for trauma. In addition, firearm-injured youth had a high burden of trauma-related diagnoses during ED visits preceding their firearm injury. These findings suggest that there is an opportunity for prevention and intervention efforts in the ED setting to prevent future injury and improve outcomes among firearm-injured youth. Lastly, most firearm-injured youth receive their emergency care exclusively in general EDs, which may have less pediatric-specific resources for injury prevention and intervention efforts.

Our findings build on prior work demonstrating increased health care utilization among youth following firearm injury compared to preinjury.5, 36 Studies comparing pediatric health care utilization for firearm-injured youth compared to other injured and noninjured youth have found that youth with firearm injury have higher odds of ED revisits and hospitalizations.37, 38 In one prior study of firearm-injured youth, 46.5% of youth had an ED visit or hospitalization in the 12 months following the index injury. Importantly, while our study demonstrated only a quarter of youth had an ED revisit, we examined a more proximal time frame to the index injury encounter (i.e., within 90 days), which may more closely represent revisits directly or indirectly related to the index injury. Future work is needed to determine if more proximate timing of interventions may be more effective in decreasing health care utilization and other adverse outcomes following firearm injury.

Furthermore, we show that a high proportion of visits before and after firearm injury are specifically for injury. This is consistent with prior literature demonstrating high risk for subsequent violent injuries, including firearm injuries, among assault-injured youth.7, 9, 39, 40 These findings support the fact that there is an opportunity for the ED to serve as a setting for prevention and intervention efforts for youth who have experienced or are at risk for firearm injuries. Types of prevention-focused interventions that may be considered in the ED setting to prevent firearm injury events include firearm safety education,41, 42 screening to identify youth at risk for future violence,43 and addressing social drivers of health.44, 45 Types of evidence-based interventions that may be considered in the ED setting after injury include case management and care coordination services,46-48 psychosocial assessments and referrals,16, 49-51 behavior change counseling,14-17 and lethal means counseling.52, 53 One specific intervention to highlight is hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIPs), which are multidisciplinary programs that utilize trauma-informed care to serve the individualized needs of violently injured patients often in conjunction with community-based partners.48, 54 HVIPs often utilize multimodal interventions including many of the aforementioned evidence-based interventions (i.e., case management, behavior change counseling, mental health assessments) in addition to other novel interventions (i.e., mentoring, legal advocacy) to ensure improved outcomes (i.e., decreased injury recidivism, mortality, criminal justice involvement) among violently injured youth. The determination of which intervention(s) to consider for a given youth will likely be influenced by patient-related factors (i.e., specific patient and family needs and preferences) and the resources available at the ED site (i.e., ED and hospital personnel, institutional resources, community-based resources).

As we strategize for implementation of ED interventions to prevent injuries and improve outcomes for firearm-injured youth, it is essential to determine where resources should be situated. Our study adds to the body of knowledge through an examination of ED site–level characteristics associated with ED utilization before, during, and after youth experience firearm injury. We demonstrate that at all time points along their longitudinal emergency care, youth are more likely to present to a general ED compared to a pediatric ED, and few youth change ED types across encounters. Given that the majority of ED-based interventions for youth with injury-related risk behaviors have been implemented in pediatric ED settings,7, 14, 16, 17 more effort is needed to determine how to implement and adapt these established interventions and other novel approaches to general ED settings where the majority of youth receive their care. Importantly, we did not detect differences in ED utilization before or after firearm injury based on the type of ED a youth presented to for their index injury. We believe that this demonstrates a shared opportunity for growth in interventions offered in all ED settings. Future work may explore the specific modifiable factors that may serve as barriers or facilitators to care for youth presenting with firearm injury to pediatric and general ED settings.

We also considered differences in ED utilization by patient-level characteristics and found differences based on youth sex and race and ethnicity. Unsurprisingly, females comprised a small proportion of our sample, which is consistent with prior literature demonstrating increased burden of firearm injuries among males.55 Notably, females demonstrated higher ED utilization both before and after firearm injury compared to males. We hypothesize this difference could potentially be related to multiple factors including the older age of our cohort. Adolescent females are known to have higher rates of prior victimization and associated mental health comorbidities and higher likelihood to utilize health care for related complaints compared to adolescent males.56-58 Importantly, given that males are disproportionately impacted by firearm injuries but are less likely to have ED visits before or after firearm injury, the index injury visit may be the best opportunity for interventions that impact their trajectory. Interestingly, we found that youth with other or missing race and ethnicity had decreased odds of ED utilization before injury. These findings may be reflective of higher baseline ED utilization among the chosen reference group (i.e., non-Hispanic White youth).59 However, these subgroup differences do not persist during visits following firearm injury, which may reflect a shared experience among all racial and ethnic groups following injury regarding increased subsequent health care needs. We found no differences in ED utilization based on urbanicity of youth residence and insurance status. Among children presenting to the ED for all complaints, prior work has demonstrated increased ED revisits among children living in urban areas, those with poor access to primary care, and those who are uninsured or with public insurance.60, 61 We hypothesize that our findings differed from prior work that included all ED presentations, unlike our cohort of only firearm-injured youth, which, similar to prior work on this subset,11, 38 had a high proportion of publicly insured youth and youth living in urban areas compared to the general population.

LIMITATIONS

First, we identified our sample population using ICD-10-CM codes, which has the potential for misclassification bias. Additionally, researchers have used a variety of approaches to categorize the pediatric capabilities of a hospital.62 Therefore, we acknowledge that our findings on differences in ED utilization by site-level characteristics may have been influenced by the classification system we chose. Next, our data set was limited to a single calendar year. As such, it is possible that some youth could have had an ED visit for firearm injury before or after the year we examined. This also limits our ability to capture utilization patterns in the 90 days prior to injury (if presenting for the index injury early in the year) or following injury (if presenting for the index injury later in the year). To account for this, we structured the cohort subsets to only include youth with index visits occurring within an appropriate time frame for outcome ascertainment, and we performed a sensitivity analysis among youth who had the opportunity for both primary outcomes with similar findings across all different analysis approaches. Finally, our findings were limited to ED encounters in eight states, which may limit the generalizability of our results. Although not a nationally representative sample, our sample had geographic diversity while ensuring all included states had high quality pediatric longitudinal data. Nonetheless, our work should be considered hypothesis generating rather than conclusive, and future studies should replicate our analysis in additional data sets.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, youth with firearm injuries have high rates of ED utilization before and after index injury visits and, among youth who return, one-quarter return with recurrent trauma. Half of youth with firearm injuries receive their emergency care before, during, and after their injury exclusively in general EDs, which may have fewer pediatric-specific resources. Further work should focus on adapting existing interventions to the general ED setting while supporting investigations of novel interventions in both general and pediatric ED settings to improve outcomes in this high-risk population.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Samaa Kemal, Elizabeth R. Alpern, and Margaret Samuels-Kalow conceived and designed the study and obtained research funding. Rebecca E. Cash and Kenneth A. Michelson provided feedback on study design. Rebecca E. Cash analyzed the data. All authors interpreted the data. Samaa Kemal drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. All authors provide approval of the final version of this manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Dr. Kemal received funding through award R01HD103637-02S1 and Drs. Cash, Michelson, Alpern, and Samuels-Kalow received funding through award R01HD103637, both from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. This work was also supported in part by the Grainger Research Program in Pediatric Emergency Medicine at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

MSK and RC's institution (Massachusetts General Hospital, MGH) has received grant funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for investigator-initiated research. SK, KM and EA's institution (Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago) has received a subcontract of this grant funding from MGH for investigator-initiated research. The authors declare no additional conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Central Distributor at https://cdors.ahrq.gov.

REFERENCES

- Note: Data are reported as aOR (95% CI).

- Abbreviation: aOR, adjusted odds ratios.