Emergency Medicine Resident Assessment of the Emergency Ultrasound Milestones and Current Training Recommendations

Abstract

Objectives

Emergency ultrasound (EUS) has been recognized as integral to the training and practice of emergency medicine (EM). The Council of Emergency Medicine Residency-Academy of Emergency Ultrasound (CORD-AEUS) consensus document provides guidelines for resident assessment and progression. The Accredited Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has adopted the EM Milestones for assessment of residents’ progress during their residency training, which includes demonstration of procedural competency in bedside ultrasound. The objective of this study was to assess EM residents’ use of ultrasound and perceptions of the proposed ultrasound milestones and guidelines for assessment.

Methods

This study is a prospective stratified cluster sample survey of all U.S. EM residency programs. Programs were stratified based on their geographic location (Northeast, South, Midwest, West), presence/absence of ultrasound fellowship program, and size of residency with programs sampled randomly from each stratum. The survey was reviewed by experts in the field and pilot tested on EM residents. Summary statistics and 95% confidence intervals account for the survey design, with sampling weights equal to the inverse of the probability of selection, and represent national estimates of all EM residents.

Results

There were 539 participants from 18 residency programs with an overall survey response rate of 85.1%. EM residents considered several applications to be core applications that were not considered core applications by CORD-AEUS (quantitative bladder volume, diagnosis of joint effusion, interstitial lung fluid, peritonsillar abscess, fetal presentation, and gestational age estimation). Of several core and advanced applications, the Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma examination, vascular access, diagnosis of pericardial effusion, and cardiac standstill were considered the most likely to be used in future clinical practice. Residents responded that procedural guidance would be more crucial to their future clinical practice than resuscitative or diagnostic ultrasound. They felt that an average of 325 (301–350) ultrasound examinations would be required to be proficient, but felt that number of examinations poorly represented their competency. They reported high levels of concern about medicolegal liability while using EUS. Eighty-nine percent of residents agreed that EUS is necessary for the practice of EM.

Conclusions

EM resident physicians’ opinion of what basic and advanced skills they are likely to utilize in their future clinical practice differs from what has been set forth by various groups of experts. Their opinion of how many ultrasound examinations should be required for competency is higher than what is currently expected during training.

Over the past 25 years, emergency ultrasound (EUS) has been recognized as integral to emergency medicine (EM) practice and training.1 The use of bedside ultrasound in the emergency department is now widespread in academic hospitals and utilization in the community setting remains variable.2, 3 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) have recently designated EUS as one of 23 required milestone competencies for EM residency graduates.4 The milestones outline five advancing skill levels, starting from Level 1 at the level of a medical student graduate to Level 5.5 Graduating residents are expected to meet Level 4 requirements on all 23 milestones. The current milestones for EUS competency during EM residency training identify image optimization, selection of the appropriate probe for each of the focused ultrasound applications, and performance of an eFAST (Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma) as Level 2, with performance of the other goal-directed focused ultrasound examinations with correct image interpretation as Level 3 and completion of a minimum of 150 scans as indicative of Level 4 milestone. Competency in the use of advanced echocardiography, transcranial Doppler, and transesophageal echocardiography is considered indicative of Level 5 competency.

A prospective survey of practicing EM physicians in both the community and the academic setting by Peck et al.6 found that practicing EM physicians met the criteria for Level 4 or 5 for the majority of the EM milestones surveyed; however, in the area of EUS, only 46% of EM physicians reported meeting a Level 4 and 1% reported meeting a Level 5. The EUS milestone stood out for having the fewest practicing physicians’ meeting the expected level of competency for residency graduation. The few number of practicing physicians meeting Level 5 was especially discordant with the other milestones, thus warranting further investigation. Although practicing physicians’ skills may not meet the skill level expected on the current milestones evaluation, there is countering evidence that what is expected by the milestones assessment may not be stringent enough. Blehar et al.7 showed that the average number of examinations that one must perform to reach proficiency varies by examination and is between 27 and 90 scans per examination type, which is above what is required for the Level 4 milestone. These discrepancies indicate a need for reassessment and improved alignment between the Level 4 and Level 5 EUS competencies and expected skills for EM practice.

The Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors-Academy of Emergency Ultrasound (CORD-AEUS) consensus document provides guidelines for resident assessment and progression of EUS training.8 It includes recommendations for organization and timing of rotations and residency competency assessment. The document also delineates basic versus advanced EUS skills. Currently, a majority of EM residency programs assess resident competency in EUS, but there is significant variation in the methods of competency assessment by these programs.9

There are no published studies evaluating resident impressions or perceptions of the current EUS milestones or the methods of evaluation. EM resident perception is a valuable tool to assist in proper implementation of milestones and may help refine the various levels of competency. This bottom-up evaluation can identify strengths and weaknesses of the current EUS milestones that can help suggest possible improvements to maximize their effectiveness as an educational tool.

The objective of this study was to assess EM residents’ use of ultrasound and perceptions of the proposed ultrasound milestones and guidelines for assessment using a population-based survey of all U.S. residency programs.

Methods

Study Design

This is a prospective cross-sectional stratified cluster survey of a nationally representative sample of EM residents within the United States. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at each participating institution as well as the institution initiating the study. Statisticians experienced in survey methodology and existing literature were utilized for guidance in study design.10

Study Population

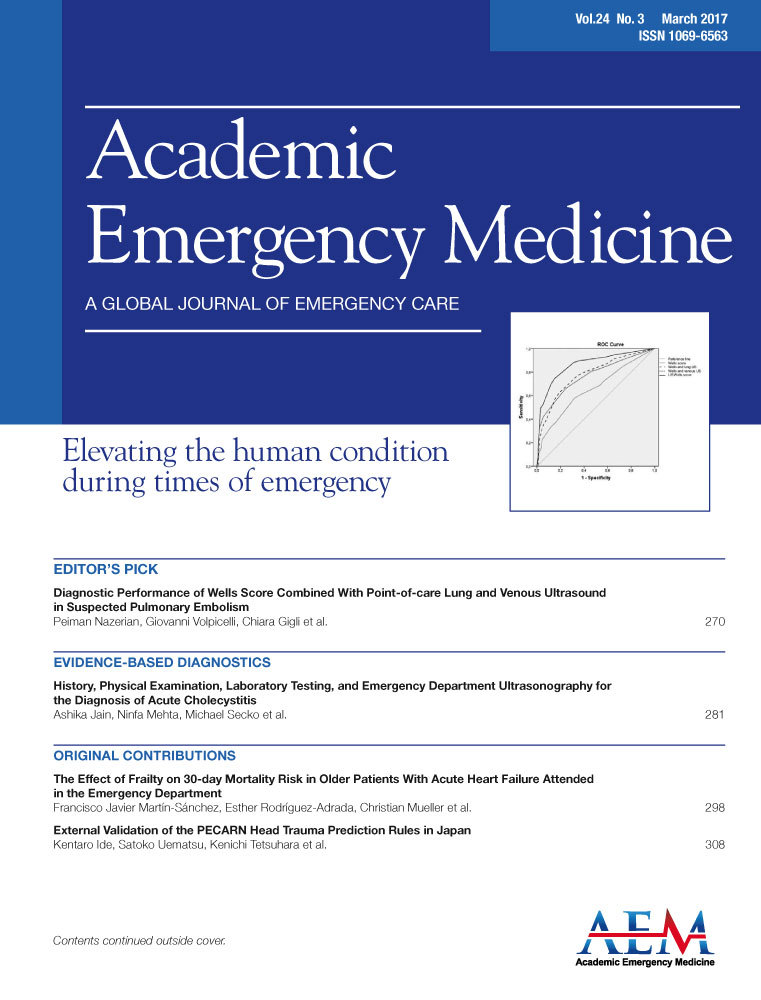

A panel of emergency ultrasound faculty determined a priori the stratification variables based on their expert opinion of factors that influence resident EUS training: size of program, geographic location, and presence/absence of an EUS fellowship program. A list of all eligible programs (the sampling frame) was compiled from the ACGME list of accredited EM residency programs.11 Programs with combined EM-Internal Medicine and EM-Pediatric residents were included. Programs not accredited through the ACGME and osteopathic programs were excluded. Determination of the number of residents at each residency program was based on the program's self-reported number of residents on the residency's website page or by telephone communication from the program's residency coordinator. After sample program selections were determined, survey site coordinators confirmed the numbers of residents in the programs. Program size categories (large programs vs. small programs) were set by review of the distribution of number of residents for all programs. We used the median of residents per program as a cut-point for determination of program size as large or small. Programs with 36 residents or above were categorized as large and programs with 35 residents or less were categorized as small. Determination of presence absence of a fellowship was determined using the Emergency Ultrasound Fellowships website.12 Designation of geographic region was based on U.S. Census Bureau Geographic areas, with the four geographic regions being West, Midwest, Northeast, and South.13 Stratification based on these three variables resulted in 16 strata (Figure 1).

Measurements

A panel of academic EUS faculty developed the survey instrument. The survey was reviewed by an additional panel of experts in the field of EUS from throughout the country. The survey was modified based on their feedback. Questions were removed and others clarified. The survey was pilot tested on a sample of EM residents for content, length, and ease of comprehension, and the survey was further modified based on their feedback. The survey was shortened and wording was clarified. The survey is available in Data Supplement S1 (available as supporting information in the online version of this paper).

Study Protocol

For each stratum, the desired number of primary samples were randomly chosen for participation with back-up programs chosen in the event that the first program(s) selected were not able to participate. One EM faculty member at each institution served as a survey site coordinator and oversaw the IRB process, consent, and survey administration. All residents within each selected program were invited for voluntary participation in the study after completion of the EM in-service examination or during scheduled educational conference time. Residents were alerted to the survey via e-mail prior to survey administration. Surveys were administered in a paper format by the survey site coordinator. No research incentives were given. Surveys were collected after completion by faculty members at each site and hard copies were mailed to the coordination institution with copies retained at each site for data preservation. Surveys were transcribed into an electronic database for data analysis.

Data Analysis

The reported summary statistics along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) account for the complex survey design (stratification and cluster sampling) and represent national estimates for all EM residents in the original sampling frame. When there was only one sampling unit per stratum, standard errors were calculated by centering the stratum mean at the grand mean. Sampling weights are equal to the inverse of the probability of program selection. All data analysis was performed using Stata v.12.1 (StataCorp). Missing data for individual questions were excluded from analysis.

We calculated the required number of subjects to survey using simple random sampling (SRS), to estimate the number of subjects needed for adequate power. We determined that 95 respondents would be required to achieve a margin of error (i.e., 95% CI) of ±0.10 for binary responses using SRS. The design effect due to cluster sampling was estimated to be 1 + (weighted mean for residents per cluster − 1) × intraclass correlation = (1 + (41 − 1) × 0.01 = 1.4. The design effect for stratification was estimated to be 3.9 using proportionate allocation to strata.14 The overall design effect was thus 3.9 × 1.4 = 5.5. Therefore, we required a sample size 5.5 times higher than our estimate based on SRS, resulting in 523 respondents. We assumed a 70% response rate. Given a weighted mean population size for each program of 41, we anticipated that 18 programs should be sampled (approx. 738 residents) for a final sample size of 523. We sampled one residency program from each stratum with one additional program from each of the two largest strata. Therefore, one program was chosen from 14 strata and two programs were chosen from each of the largest two strata, to reach the target of 18 programs sampled. Figure 1 shows a schematic of the sampling frame as well the stratification and sampling design.

Results

A total of 539 residents participated from 18 EM residency programs. The first randomly chosen program for each sample participated in seven instances. The second back-up program participated in seven instances and the third back-up program was necessary for three samples. Surveys were administered between February 25, 2015, and September 28, 2015, with 10 programs administering the survey on the day of the in-service examination and the additional eight programs administering the survey at resident educational conferences. The overall survey response rate was 85.1% with 633 residents eligible for participation. The median number of resident respondents per program was 28 (interquartile range [IQR] = 24 to 34). The denominator for the response rate includes all current residents in the selected programs. Survey nonrespondents includes both residents not present at the time the survey was administered and residents who declined to participate. Individual question nonresponse rates were quite low overall with a median nonresponse rate of 0.74% and IQR of 0.37% to 2.3%. Given the overall low item nonresponse rates we did not use multiple imputation or other methods to account for missing data.

Residents in their first, second, and third years of postgraduate (PGY1–3) training were nearly equally represented, consisting of 31, 31, and 27% of residents, respectively. PGY4 and PGY5 residents made up smaller percentages, at 9 and 2% each. Ultrasound experience varied widely, with 10% (95% CI = 5% to 22%) having performed fewer than 50 scans, 38% (20%–61%) with 50–150 scans, 40% (24%–59%) with 151–300 scans, and 11% (3%–32%) with more than 300 ultrasound examinations. Residents reported having performed an average of 166 (95% CI = 109 to 223) examinationss at the time of the survey. By year, residents in PGY1–5 had performed an average (95% CI) of 102 (29–176), 167 (77–258), 220 (162–278), 195 (166–223), and 236 (191–281) ultrasound examinations respectively. The majority of residents self-reported their EUS skill level as intermediate (78.9% [73%–84%]), with 7.7% (4%–15%) considering themselves novice and 13.4% (6%–27%) advanced.

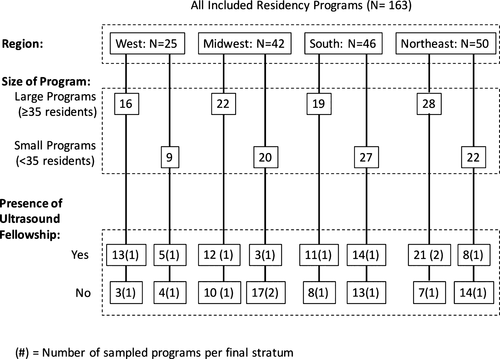

Resident categorization of each application as either a core or an advanced skill is presented in Figure 2. The majority of residents identified core ultrasound skills in agreement with the CORD-AEUS consensus statement, with the exception of undifferentiated vitreous pathology (31.9% [21%–46%] responded as core skill). Applications that are not considered to be core applications by CORD-AEUS but were considered to be core applications by a majority of current EM residents include quantitative bladder volume (85% [70%–93%]), joint effusion (66% [53%–78%]), interstitial lung fluid (71% [41%–90%]), fetal presentation (71% [40%–90%]), gestational age estimation (60% [13%–93%]), and peritonsillar abscess (51% [38%–65%]).

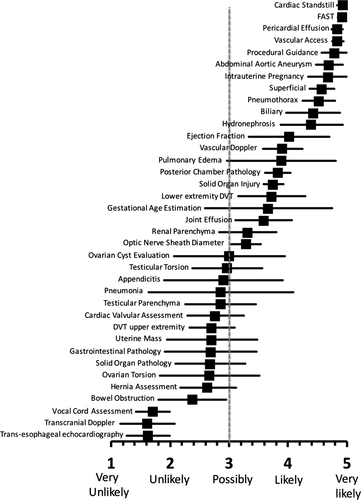

Resident opinion regarding which ultrasound applications they see themselves using in their future clinical practice is presented in Figure 3. Cardiac standstill, the FAST examination, pericardial effusion, and vascular access were considered the most likely to be used while transesophageal echocardiography, transcranial Doppler, and vocal cord assessment were the least likely to be used. Residents were asked which ultrasound applications they saw as most important to their future clinical practice; 41% (20%–68%) responded that procedural guidance would be most important, 31% (22%–43%) considered ultrasound for resuscitation to be most important, and 27% (12%–49%) considered diagnostic ultrasound most important.

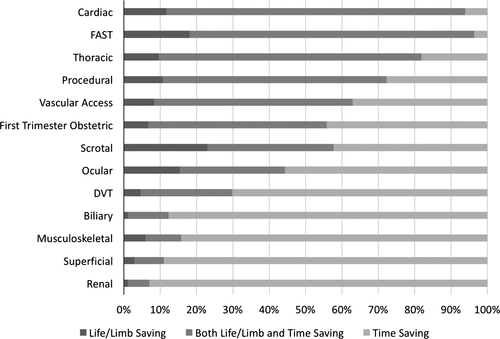

Applications considered most life or limb-saving and time-saving included cardiac ultrasound (82% [77%–86%]), the FAST examination (78% [72%–83%]), and thoracic ultrasound (72% [57%–83%]; Figure 4). Applications considered the most time-saving but not necessarily life- or limb-saving included renal ultrasound (93% [85%–97%]), superficial (89% [82%–93%]), musculoskeletal (84% [76%–89%]), and biliary (88% [78%–93%]).

Residents were varied on their opinion of the Registered Diagnostic Medical Sonography (RDMS) examination as necessary to validate competency in EUS with 29% (19%–42%) agreeing or strongly agreeing, 40% (26%–57%) disagreeing or strongly disagreeing, and 31% (22%–41%) responding neither. When asked if they thought that certification would help them gain credibility, however, 75% (60%–86%) agreed or strongly agreed.

When asked about concern regarding medicolegal liability while using EUS, 48% (28%–68%) of residents reported concern when using core applications compared to 73% (63%–82%) for advanced applications. Residents also agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that EUS is necessary for the practice of EM in the community setting 90% (86%–92%) of the time.

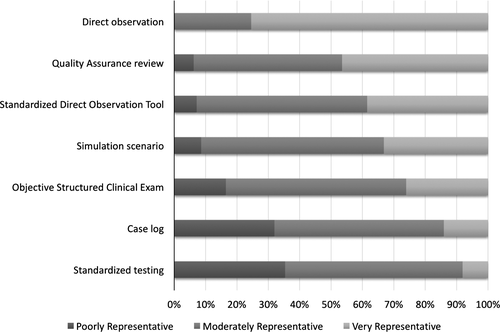

A large percentage of residents believe they can obtain Level 4 milestones while in residency, with 82% (70%–90%) agreeing or strongly agreeing. There was a much higher rate of strong disagreement or disagreement for the feasibility of completing the Level 5 milestone (24% [16%–35%]) than the Level 4 milestone (1.5% [0.45%–7%]). The majority of residents either strongly agreed (27% [15%–43%]) or agreed (55% [46%–63%]) that the number of ultrasound examinations performed in residency alone does not ensure competency. Eighty-five percent (75%–92%) of residents felt as though they should be assessed on their ability to integrate ultrasound into clinical practice. However, residents felt that on average 325 (301–348) ultrasound examinations would be required to be proficient as a practicing emergency physician and they felt that on average 288 (270–307) scans should be obtained during residency. Resident opinion of the ability of various methods of assessment to represent their competency in using EUS is presented in Figure 5. The only method that a majority of residents felt was very representative was direct observation (75% [64%–84%]). Standardized testing (35% [27%–45%]) and case logs (32% [22%–44%]) were methods of assessment that were considered to be poorly representative of skills by the greatest number of residents.

Discussion

This study is the largest, most comprehensive study to date on resident physician current and anticipated future use of EUS and their perceptions of the EUS milestones. Within the residents’ responses there is an overall theme that procedural and critical ultrasound applications are most valuable. Nearly all residents plan to use ultrasound for detection of cardiac standstill and for vascular access. Many applications that are considered advanced by CORD-AEUS were considered to be core applications by a majority of current EM residents and include quantitative bladder volume, interstitial lung fluid, fetal presentation, joint effusion, gestational age estimation, and peritonsillar abscess. These applications are targets to reconsider for additions to the CORD-AEUS list of core applications.

Current milestone evaluation guidelines conflict with resident opinion of the applications and number of examinations that they performing and anticipate needing for future practice. The current Level 4 ultrasound milestone is marked by the performance of 150 goal-directed ultrasound examinations. More than 50% of the respondents to this survey had performed greater than 150 ultrasound examinations, yet when assessing their skills, few consider themselves to be advanced. Additionally, residents report achieving the endpoint of 150 ultrasound examinations in the second year of residency. This survey suggests that residents do not consider the minimum number of examinations listed as Level 4 to be appropriate numbers and that number of examinations performed do not equate to competency. Additionally, residents report lack of comfort with the applications listed under the Level 5 milestone competencies. Transesophageal echocardiography and transcranial Doppler are not typically performed by practicing emergency physicians. These applications may be performed in practice, though rarely, by those who have trained at a fellowship level. Thus, the results of this survey indicate that EUS skills of graduating residents exceed current Level 4 milestones and fall below the Level 5 milestones, leaving a gap in the continuum on which they are assessed. There is an opportunity for the milestones evaluation to be revised to address these discrepancies.

Recognition of EUS competency currently has no uniform reference standard. Nearly all ACGME EM residency programs currently assess these ultrasound competencies through image quality assurance and direct observation during clinical shifts.9 Fortunately, these current assessment methods were felt by nearly all residents to be moderately or very representative of procedural competency. These methods of evaluation are among the most time-intensive for faculty, presenting a challenge for accurately evaluating all graduating residents. This finding may be limited because resident perception of value of educational techniques may be based on the techniques used at their institution.

Residents did not believe that the RDMS examination was necessary to validate competency in EUS, but 76% agreed or strongly agreed that certification of some kind would help them gain credibility. This suggests that while EM residents may not feel that certification is necessary, they do believe that it could assist them in gaining future credibility. The may stem from continued resident perception of poor recognition of EUS outside of the EM community. Another possible reason for this finding may be that RDMS certification is not specific to EUS, and residents anticipate an EM-based certification program for the future.

Limitations

Survey methodology has inherent limitations. We stratified based on the most likely determinants of variation in responses within the population, program size, presence/absence of fellowship, and geographic location, thus optimizing the external validity of the study and minimizing chances that certain groups would be under- or oversampled. Other variables that have not been accounted for are likely at play, such as number of ultrasound-trained faculty members, varying exposure to different US applications, presence or absence of credentialing and billing programs, and overall institutional support for EUS. Our survey instrument was pilot-tested; however, it was not validated. Our methods of data collection to determine stratification may have led to errors in stratifying programs. Although most of the programs were able to administer the survey on the day of the in-service examination, the survey was administered at a different point in the academic year for some programs. Therefore, the pool of respondents is not completely homogenous in respect to their degree of residency experience.

Conclusions

There is a divergence between currently published educational guidelines and learner perceived core skills and advanced skills for these learners. These learners also believe that many more ultrasound examinations should be required as part of their education in emergency ultrasound. These findings provide guidance for next steps in tailoring emergency medicine resident emergency ultrasound education and future iterations of the emergency ultrasound milestones.

We thank Dr. Phillip J. Hoverstadt and Dr. Albert B. Fiorello for their contributions.