Neutralizing Deviance at State-owned Enterprises: The Case of South African Airways

Abstract

This article investigates how boards of directors and auditors retrospectively reflect on and justify their role in the breakdown of governance systems. We focus on state capture in South Africa where major corruption scandals have crippled the public sector. These scandals have been investigated by a special commission of inquiry, the ‘Zondo Commission', which offers a rich set of data for uncovering how individuals attempt to justify their ‘deviant’ behaviour. Our focus is on the crisis at South African Airways (SAA), where the Zondo Commission concluded that the airline had repeatedly disregarded relevant laws and experienced a steep governance decline. Despite this malpractice, SAA's former auditors, PwC and joint audit partner Nkonki Incorporated, consistently gave SAA unqualified audit opinions. Only after intervention by the South African Auditor General were deficiencies exposed in SAA's financial and governance structures. Our analysis identifies various neutralization techniques used by implicated individuals to cast doubt on responsibility for wrongdoing and garner sympathy where deflection was not feasible. The method involves documentary analysis, focusing on witness transcripts and other evidence published by the Zondo Commission, SAA's integrated reports, and select media articles. In addition to dealing with a novel set of data, this paper adds to the limited body of work dealing with governance in state-owned enterprises, particularly in developing economies. The research also provides an account of how deviance theory is operationalized in the context of governance and audit, something which has not yet been explored in detail.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) constitute approximately one-fifth of the world's largest enterprises. If they fail, the ramifications are substantial (OECD, 2018; Ackers and Adebayo, 2022) because SOEs play a key role in implementing public policy and addressing economic problems arising from natural monopolies (Baum et al., 2019). Therefore, SOEs must serve the public interest with governance and accountability mechanisms which ensure responsible use of taxpayers’ funds. These mechanisms include effective systems of internal control complemented by robust internal and external audits (Hassan et al., 2023). There are, however, only a handful of studies that investigate how accountability mechanisms function at SOEs and the problems that are encountered by these organizations (Baum et al., 2019; Dzomira, 2020). In particular, researchers have called for case studies to provide in-depth insights into the operation and interaction between multiple governance mechanisms, especially when governance failures have occurred (Grossi et al., 2015; Daiser et al., 2017).

In this paper, we undertake a case study approach to analyze the near-collapse of South African Airways (SAA) and how individuals key to upholding the airline's accountability mechanisms justified their actions during the crisis period. Specifically, we consider how SAA's board and its auditors rationalized or justified behaviour which, under normal circumstances, would be regarded as contravening codified governance principles1 and related legalization. This departs from the traditional approach of examining how governance mechanisms (like monitoring by board members and external audits) enable improved organizational performance and accountability (Grossi et al., 2015). As its basis, our research uses the conclusions of recent independent judicial inquiries held in South Africa into SAA's breakdown. The paper makes four key contributions.

Firstly, research on SOEs has increased recently but most SOE studies apply a predominantly quantitative approach (Daiser et al., 2017). While these studies have generated valuable insights into the determinants underlying SOEs’ governance performance (such as the impact of audit committees on financial or social performances) they overlook the possibility of governance mechanisms being ‘captured’ and how the involved individuals rationalize or justify the misapplication of or departure from generally accepted governance standards.

Secondly, most SOE studies investigate China, India, the US, and European countries but few focus on African countries (exceptions include Abuazza et al., 2015; Bananuka et al., 2018). Our study investigates South Africa, which is one of the key economies in Africa, adding to the body of work on under-researched jurisdictions.

Thirdly, this is one the first governance-related studies of South African ‘state capture’, which is the common term used to describe the process by which private individuals and companies commandeered South African organs of state, including prominent SOEs, to redirect public resources into their own hands (Gevisser, 2019). We draw on recently concluded investigations of the Zondo Commission which investigated state capture across the South African public sector, including SOEs. The Commission's extensive investigations offer a unique insight into governance and audit crises at a SOE as witnesses testified under oath. Many documents that are not usually available to researchers were made public by the Zondo Commission, thereby offering a rich set of data for examining how the Board and external auditors of an important SOE rationalized accusations of malpractice and non-compliance with existing governance norms and regulations. Although data are drawn from a single case, the explication of how key individuals in SAA's governance mechanisms attempt to defend their conduct provides insights that are relevant for examining other governance-related failures at SOEs in South Africa and internationally.

Finally, our analysis of SAA's crisis is informed by the neutralization techniques framework (Sykes and Matza, 1957; Harris, 2022), which has been used in different domains (e.g., Hinduja, 2007; Fooks et al., 2013). The framework has, however, seen limited application in accounting scholarship. Our study reveals the framework's relevance for understanding the role of individuals when governance—including audit—mechanisms fail.

NEUTRALIZATION TECHNIQUES

Company failures have made international headlines in recent years. From Enron's collapse in the US in 2001 to Wirecard in Germany in 2020, most company failures have exposed serious crises in companies’ governance and audit arrangements. Extensive literature has emerged linking weak corporate governance to deviant and non-compliant behaviour by individuals within and outside the organization (Felo, 2011).

Although they are often used interchangeably the meanings of the terms ‘deviance’ and ‘non-compliance’ do differ slightly. ‘Deviance’ refers to any behaviour that violates social norms and expectations notwithstanding that these are often not legislated or formally codified. ‘Non-compliance’ refers to failure to obey formal rules and regulations (Mitra et al., 2021). Owing to its nature as a social norm, what is perceived as deviant behaviour is primarily the result of an individual's learning process which occurs through their association with those who approve of deviant behaviour and those who do not. These associations, which will influence an individual's actions, are not limited to an individual's immediate social setting but will be vulnerable to influences from larger institutional and cultural arrangements (Vaughan, 2002). Individuals generally have multiple differential associations (e.g., family and peers) but the associational importance of an individual's workplace is significant given the amount of time individuals spend in the workplace and the (financially) important role this occupies in their lives (Piquero et al., 2005). Examples of audit-related norms include how auditors are trained within their firms to apply auditing standards and guidelines. Although audit standards such as those issued by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) provide a framework for how audits are to be conducted, within this framework, auditors have substantial discretion as judgement is inherent in many auditing tasks such as assessing materiality and risks or concluding on the sufficiency and appropriateness of evidence obtained during audit engagements. The same is true in the context of boards of directors. Codes of best practice have emerged but these typically provide broad principles according to which directors are expected to operate. Detailed prescriptions catering for how every issue encountered when overseeing an organization's strategy, risk management, and core operations are seldom available. This is the case even when governance codes are complemented by legislation. Similar to the situation encountered with auditors (and other professionals), directors are trained to apply guidelines but also to rely on rules of thumb, subjective sense-making, and ‘gut feel’ (Pentland and Rueter, 1994).

To explain the development of the specific drivers and motives associated with misbehaviour (understood here as encompassing both deviant and non-compliant behaviours), Sykes and Matza (1957) proposed a theory of delinquency which emphasizes that individuals become delinquent by learning techniques that allow them to justify their behaviour rather than learning criminal behaviour (Piquero et al., 2005). These learned techniques allow individuals to justify or neutralize their behaviour, enabling them to alternate between deviant and functional behaviours without feeling deeply guilty (Harris, 2022; Piquero et al., 2005). In their original framework, Sykes and Matza (1957) outline five neutralization techniques: (1) ‘denial of responsibility’, where individuals claim they did not mean to deviate; (2) ‘denial of injury’, involving denial of harm; (3) ‘denial of victims’, centring on abjuration of casualties; (4) ‘condemning the condemners’, involving attacking critics; and finally (5) ‘appeals to higher loyalties’, which focuses on elevating other norms.

Sykes and Matza (1957, p. 666) claim that neutralizations ‘precede deviant behaviour and make deviant behaviour possible’. While some studies support this view (e.g., Pogrebin et al., 1992), researchers have found evidence that neutralization practices can occur both before and after episodes of deviance because justifications employed as neutralizations in one case may be used as rationalizations by the same offender in a later incident (Harris, 2022; Vitell and Groves, 1987). Hence, we follow Kaptein and Van Helvoort (2019, p. 1261) who argue against distinguishing between neutralization and rationalizations, as such terms ‘are increasingly used interchangeably in the literature covering both ex-ante and ex post arguments’.

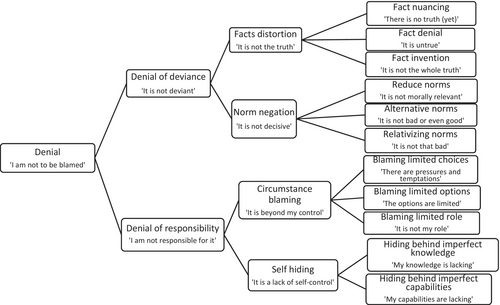

One criticism of neutralization theory is its limited development over time with most studies following Sykes and Matza's original framework (Maruna and Copes, 2005). Some seek to address this under-theorization, including risks of arbitrariness and inconsistency associated with the way neutralization techniques have been named and selected by Sykes and Matza (1957). Kaptein and Van Helvoort (2019), for example, provide a comprehensive literature review and develop a model of neutralization techniques that deductively devises a basic structure that helps to connect categories of neutralization techniques. They distinguish between two main techniques—denial of deviance and denial of responsibility—arguing that these are logical and exhaustive given that they capture the essence of neutralization. Denial of deviance can be perceived as the higher-order variant because individuals employing these strategies accept their actions but claim they did not result in deviance from explicit or implicit contextual norms (‘It is not deviant’). In the case of the lower-order variant, denial of responsibility, techniques are used that imply a cognitive acceptance of misbehaviour, with the subsequent justification of behaviour provided on the ground of diminished responsibility (‘I am not responsible for it’) (Kaptein and Van Helvoort, 2019).

The literature subdivides denial of deviance and denial of responsibility into four categories with ‘facts distortion’ and ‘norm negation’ as second-order dimensions of ‘denial of deviance’, and ‘circumstance blaming’ and ‘self-hiding’ as second-order dimensions of ‘denial of responsibility’. Kaptein and Van Helvoort (2019) further subdivide these four categories into 12 broad techniques. We draw on these techniques, and Harris's (2022) recent adaptation, to investigate how individuals inside and outside SAA mobilize neutralization techniques to justify behaviour which contributed to the airline's collapse. Our adapted model, depicted in Figure 1 and including a brief explanation of each strategy, uses a decision tree to highlight how the selection of initial neutralization techniques influence defence strategies available to individuals in consecutive stages.

We draw on neutralization theory to understand how individuals involved with SAA's governance and audit crisis mobilize neutralization techniques to justify their role. Whilst our focus is on SAA Board members and SAA's private sector auditors, we also investigate the role of the Auditor General of South Africa (AGSA, hereafter AG) and the Department of Public Enterprises (the South African government department responsible for overseeing SOEs, including SAA) insofar as their actions are interconnected with the activities of the Board and external auditors.

Depending on the setting in which individuals operate, different incentives and options exist for rationalizing norm infringement. We hypothesize that individuals will rely on denial of deviance strategies when facts associated with the norm violation might be disputed, or perpetrators question the accuser's interpretation of the norm. The latter is more likely if governance or audit standards are ambiguously defined, leaving scope for individuals to justify behaviour which, even if not in direct violation of those standards, could be construed as inappropriate (Harber et al., 2023).

As discussed below, the formal framework of governance and audit in relation to the public sector in South Africa is generally acknowledged to be of high quality (Maroun et al., 2014). We expect this to render denial of deviance strategies less attractive for rule infringers, especially if evidence is undisputed. In these circumstances, denial of responsibility constitutes a more feasible approach if individuals believe their norm infringement will be excused because of the unique circumstances in which they found themselves or the knowledge and capability deficiencies they claim to have faced. Owing to SAA's position as a SOE, and the unique political-economy dynamics such as government officials being subordinate to hierarchically superior government politicians, we expect denial of responsibility to have been a frequently applied neutralization strategy by individuals involved in SAA's audit and governance crises. Further, the mobilization of denial or responsibility strategies is likely to have been enhanced because of the volume of evidence collected by the Zondo Commission, which would have reduced the probability, as assessed by norm infringers, to employ successful denial of deviance strategies.

GOVERNANCE AND AUDIT OF STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES IN SOUTH AFRICA

Individual governments, the World Bank (2014), and the OECD (2018) have developed SOE-specific governance best practice guidelines. Ackers and Adebayo (2022) find that South Africa demonstrates a high level of conformity between their corporate governance codes and those international guidelines. The South African Public Finance Management Act (PFMA), introduced in 1999, King IV (IoD, 2016), and the Protocol on Corporate Governance in the Public Sector are considered world class in terms of the regulatory and governance structures laid out for SOEs (Ackers and Adebayo, 2022).

The PFMA focuses specifically on the functions of SOEs and the related duties of board members and accounting officers. The focus of the PFMA and related guidelines is on ensuring ‘good’ governance and eliminating agency problems. SOEs are at particular risk of being affected by principal–agent problems as citizens effectively ‘appoint’ the state as principal to oversee SOEs but state owners can be tempted to pursue their political or other objectives (Allini et al., 2016). These risks are exacerbated by the nature of the relationship between the state and the economy often being blurred in SOEs (Roper and Schoenberger-Orgad, 2011).

Similarly, research has found that SOEs tend to be more prone to corruption than privately owned companies due to potential interference by public sector officials involved in the state ownership governance structure, especially in emerging markets (Apriliyanti and Kristiansen, 2019). For example, inferential work suggests that for SOEs where there is significant state control, audit fees tend to be higher (Andrews and Ferry, 2021), implying that the SOE structure can influence audit characteristics in a potentially negative manner.

Fiduciary duties applying to directors of South African SOEs are entrenched in the PFMA and overlap, in many ways, with those applying to directors of private sector companies in terms of the South African Companies Act (see Section 76). For example, directors of both private companies and SOEs must act in good faith, with reasonable care and skill and in the best interest of their organizations. However, the PFMA (Section 50) also lists SOE-specific duties including the requirement for Boards of SOEs to: (i) act with fidelity, honesty, and integrity; (ii) disclose to the Minister of Finance all material facts which in any way may influence the decisions or actions of the Minister; and (iii) prevent any prejudice to the financial interests of the state. The PFMA places stringent financial reporting duties on Boards of SOEs, such as information requirements towards Parliament and the government department charged with oversight.

South African SOEs are either audited by the AG or another auditor acting on the AG's behalf. Several requirements apply to auditors of SOEs, some of which are relevant to the audit profession generally while others specifically apply to auditors of SOEs. Firstly, auditors must comply with all relevant ethical requirements, including those contained in codes of best practice and enshrined in the relevant laws (IAASB,2 2009b). Secondly, the auditor needs to exercise professional judgement and scepticism.3 Thirdly, audits must be conducted with the express purpose of collecting sufficient audit evidence on which to base the opinion on the client's financial statements (IAASB, 2009a, 2009b). The PFMA and Public Audit Act (PAA) create additional requirements for auditors of SOEs, in particular the need to consider the compliance of the auditee with legislation, evaluating the operating effectiveness of SOEs’ internal processes, and the obligation to report non-compliance to the appropriate authorities. Audits of SOEs, however, are not performed with the express purpose of detecting fraud, and inherent limitations of an audit mean that some fraud may never be uncovered (IAASB, 2009c).

Even though South Africa boasts impressive regulations for SOEs and associated governance requirements, deficiencies in management and oversight continue to undermine SOEs’ ability to fulfil state-provided mandates. Examples include weaknesses in the design and implementation of controls over core processes (Myeza et al., 2021), ineffective audit committees (Dzomira, 2020), and inadequate involvement by the respective government departments in their role as shareholders (Thomas, 2012). A root cause analysis of these problems is beyond the scope of this paper. Relevant to this research is that breaches of statutory and fiduciary duties are alleged at South African SOEs, including SAA. These problems are widely publicized by the financial press and were investigated by the Zondo Commission. How the individuals implicated in breaches of statutory and fiduciary duties attempt to neutralize allegations of impropriety put to them by courts of law or commissions of enquiry is the focal point for the remainder of this paper. Indeed, we address a need for research in this area, given that the ‘… importance of SOEs, the problems of mismanagement, lack of transparency in effective control and corruption, and public pressure are increasingly queried by the public …’ (Phuong et al., 2020, p. 668) and require urgent attention from the academic community.

RESEARCH ISSUE AND METHODOLOGY

We employ a qualitative research method applying content analysis of available documentary evidence to study a specific SOE case. As Grossi et al. (2015, p. 282) argue, ‘… qualitative studies are required to further our knowledge of the subtleties of these adaptive and enduring organizations and for substance and insights to prevail over superficialities’.

Our selected case, SAA, experienced financial and governance crises for many years. In November 2019, SAA aircraft were grounded due to an eight-day strike and in December 2019 SAA was placed under Business Rescue. In January 2020, the SAA Business Rescue Practitioners secured funding from the Development Bank of Southern Africa to formulate a business rescue plan. SAA took urgent action to conserve cash in February 2020, including targeted changes to the route network, deployment of more fuel-efficient aircraft, and renegotiation of key contracts with suppliers. In March 2020, SAA's Business Rescue Practitioners requested an extension from creditors to extend the publication of the Business Rescue Plan. The timing of SAA's financial and governance failures coincided with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and, on 24 March 2020, SAA suspended all domestic flights.

SAA's long overdue 2017/18 financial report, presented in September 2022, showed that in 2017/18, the airline had debts of SAR8.4 billion (US$0.5 billion), and total liabilities of SAR26.7 billion (US$1.5 billion), exceeding total assets of SAR13.4 billion (US$0.8 billion). The South African Government had injected SAR10 billion (US$0.6 billion) during the financial year but the airline made a total operating loss of SAR5.4 billion (US$0.3 billion) (SAA, 2022).

In June 2021, the Government announced it would sell its majority stake in SAA to a private consortium in order to provide SAA with a much-needed capital boost. However, after nearly three years of negotiations, the deal fell through in March 2024, leaving SAA without the expected financial injection (ch-aviation, 2024).

Data Collection

We relied on three data sources. Firstly, we examined reports, interview transcripts, and primary documents published by the State Capture Commission, or ‘Zondo Commission’ (chaired by Chief Justice of South Africa Raymond Zondo).4 The Zondo Commission investigated SAA and its associated companies, focusing on the SAA Board of Directors, given its chief role in financial accountability. Unlike other state capture cases investigated, the SAA investigation also focused significantly on the role of auditors. We analyzed published transcripts from interviews held for the Commission's investigation in addition to internal documents from the AG and PwC/Nkonki published by the Commission.

Secondly, we relied on a trial brought forward by the South Africa-based Organisation Undoing Tax Abuse (OUTA) and the South African Airways Pilot Association (SAAPA) in which they (successfully) sought an order to declare former SAA Board Chair (Ms Myeni) a delinquent director for life. During the trial in 2020, six witnesses testified against Myeni including four former SAA executives, a National Treasury official, and a practicing attorney. Recordings of the court sessions were available via eNews Channel Africa, and we focused on two witness statements for additional information to confirm and complement the details provided by the Zondo Commission's witnesses. Table 1 includes all witness testimonials analyzed, which we selected based on their anticipated relevance to SAA's audit and governance failures. The bracketed names in column (1) are used in our discussion.

| Zondo Commission | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Function | Day(s) at the Zondo Commission | Number of transcription pages |

Mr Sokombela (AG witness) |

Senior Engagement Manager for the audit of SAA at the AGSA | Days 216 & 217 20–21 February 2020 |

131 + 121 = 252 |

Mr Mothibe (PwC witness) |

PwC audit partner assigned to the SAA audit for the years 2014–2016 | Days 233 & 234 16–17 July 2020 |

232 + 255 = 487 |

Ms Kwinana (SAA ARC witness) |

Former non-executive board member of SAA; Chair of the SAA Technical Board; and Chair of the SAA's Audit and Risk Committee | Days 296 & 301 2 &7 November 2020 |

257 + 243 = 500 |

| Ms Memela (SAA procurement witness) | Former SAA Technical procurement head | Day 209 7 February 2020 |

188 |

| Ms Myeni (SAA Board witness) | Former SAA Board chairperson | Days 298–300 4–6 November 2020 |

120 + 148 + 265 = 533 |

| Trial brought forward by OUTA and SAPA—Myeni's delinquency case | |||

| Ms Halstead (National Treasury witness) | Former Chief Director Sector Oversight at National Treasury, responsible for overseeing SOEs | 12 February 2020 | Transcription of court session (4hrs 16min) |

| Mr Wolf Meyer (SAA CFO) | Former SAA CFO | 18 February 2020 | Transcription of court session (2hrs 40min) |

Thirdly, we analyzed SAA's integrated reports, available since 2013. The reports provided a ‘base’ position on the organization's governance according to its Board of Directors and were useful for contrasting with evidence led before the Zondo Commission and Myeni's delinquency trial.

Data Analysis

We first coded the witness transcripts. This was done manually in order to identify points dealing directly or indirectly with SAA's governance mechanisms, including external audit. These points were treated as open codes. Examples include different challenges encountered at SAA, how the individuals understood the underlying issues, steps taken (if any), and the rationale for following a specific course of action. To avoid curtailing the analysis, the open codes were not pre-determined. They were developed iteratively based on the lead researcher's judgement as source material was examined (adapted from Holland, 1998 and Harber et al., 2023).

After the transcripts had been analyzed, we aggregated open codes covering the same issues or themes. The final set of open codes was tagged with one or more neutralization techniques (axial codes). To provide structure, limit bias, and facilitate the organization of findings, the neutralization techniques shown in Figure 1 were used. The researchers focused on techniques such as ‘reducing norms’, ‘blaming limited choices’, or ‘hiding behind imperfect knowledge’ rather than broader categorizations to avoid overlooking nuances in how accusations of deviant behaviour were neutralized by those implicated in governance failures at SAA.

The qualitative thematic analysis used to process data sources may provide a less detailed description of the data, in aggregate, compared to more inductive coding strategies. Nevertheless, the analysis protocol was considered most appropriate because it is well-suited for generating the detailed analyses necessary for highlighting individuals’ use of neutralization techniques (De Widt et al., 2022; Hayes, 1997). The researchers’ direct involvement in data collection and analysis and use of professional judgement are also a defining feature of interpretive research. Nevertheless, validity and reliability safeguards were introduced.

Validity and Reliability

To strenghten the validity of the findings, the identification of various neutralization techniques encompassed extensive discussion within the research team. For consistency, we ‘tagged’ each open code with one or more neutralization techniques and extensively disussed within the research team our identification of neutralization techniques and explanation of how these were operationalized. A qualitative ‘triangulation’ of neutralization techniques was also used.

Firstly, we continuously compared witness transcripts with written statements and additional evidence submitted by witnesses to the Zondo Commission to ensure that the neutralization techniques identified were complete and understood correctly. Secondly, data from Myeni's delinquency trial and SAA corporate reports were considered. These sources were coded in a similar way to witness testimony and used to confirm that no additional neutralization techniques or variations in techniques used during the Zondo Commission were overlooked. Thirdly, the researchers also consulted statements made by the individuals appearing before the Zondo Commission in the financial press. The aim was to confirm that the neutralization techniques were not being materially modified because of, for example, guidance provided by legal advisors or the formal processes followed when evidence was led during the Zondo Commission. Fourthly, findings by the Zondo Commission that audit deficiencies had occurred were confirmed in a separate investigation by the South African Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (IRBA) into the conduct of SAA's lead external auditors (i.e., PwC auditor Mothibe and Nkonki auditor Masasa). The investigations resulted in fines for deficiencies in the SAA audit.5 PwC acknowledged in a statement issued following the release of the Zondo Commission's report on SAA (on 4 January 2022) that ‘the firm's work at SAA fell below the professional standards expected of us and that we demand of ourselves’.6 An exhaustive review of media sources and the IRBA investigation was not conducted. These sources were examined only to a point of saturation which was indicated by public statements being repetitive and reaffirming what was already revealed by the open and axial coding of witness statements.

At the suggestion of one of the anonymous reviewers, the researchers considered the risk of witness statements reflecting the respective advocate's legal strategy rather than an account by the implicated individuals. This risk was determined to be low.7 Evidence was led under oath by legal advisors subject to stringent ethical and legal requirements, including rules for leading of evidence. The Commission was open to the public and all testimony has been made publicly available reducing further the possibility that witness statements are the product of undue influence by legal representatives. In addition, a comparison of witness statements, information from the OUTA case, and details from the SAA corporate reports revealed no material variations in the neutralization techniques that were derived using only an analysis of the witness statements.

For the same reasons, the researchers chose not to conduct individual interviews. This overcomes the risk of interviewees modifying responses or withholding information when engaging with academics. Individuals appearing before the Zondo Commission presented their version of events during a formal legal process which included the cross-examination of witnesses. This, coupled with the legal and financial ramifications for witnesses deliberately withholding information or misrepresenting circumstances, affirms the quality of the data. Refer to Table 1 for a summary of key witness testimonies.

Finally, we recognize that the Zondo Commission operated in a political context but the Commission was chaired by an experienced and independent judge. The Commission's terms of reference were published and proceedings were covered by the local press. As a result, the Commission's investigations resulted in a rich and unique set of data, the quality of which cannot be replicated by academics. Rather than being a limitation, that this study's results are derived from testimony led before the Commission makes a substantial and methodological contribution.

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND AUDIT PERFORMANCE: NEUTRALIZATION OF BEHAVIOURS

SAA experienced financial, business, and governance crises for several years with many problems already having started around 2010; however, it took many years for SAA's problems to be revealed. To understand this delay, we need to consider the simultaneous occurrence of a crisis in SAA's audit and governance arrangements. The following sections analyze to what extent key individuals draw on neutralization techniques when reflecting on their role during SAA's crisis period, beginning with a discussion of SAA's audit failure, and then moving to failures in SAA's corporate governance mechanisms.

Justifying the Failures of Audit Mechanisms at SAA

During the crisis period – and its leadup – at SAA, the airline was initially audited by private sector audit firms which changed in 2016/17 when the AG took over SAA's audit. As with other South African SOEs, the AG decides whether it audits those entities or allows the audits to be conducted by private firms. In the latter case, the AG plays an oversight role on the audit engagement.

Before the AG took over, SAA was initially audited by KPMG. PwC and Nkonki Inc (hereafter PwC/Nkonki) became joint auditors in 2012. In each of the following five consecutive years, PwC/Nkonki issued unqualified audit opinions on SAA's financial statements. However, in the first financial year in which the AG audited SAA, a qualified opinion was issued after the discovery of major accounting irregularities, many of which related to prior financial years. To explain the change from a clean audit to a qualified audit, including the need for restatements, following the change in SAA's auditor, the Zondo Commission heard evidence from witnesses who had been directly involved with SAA's audit function, including from the AG, PwC/Nkonki, and SAA's Audit and Risk Committee (ARC).

The Commission concludes that SAA's external auditors appointed for the period 2012–2016 ‘failed dismally to detect fraud and corruption’. We analyze three main issues in relation to SAA's external audit that emerged from the evidence presented to the Commission: (1) the irregularity of the external auditor appointment from the second year onwards; (2) PwC/Nkonki failing to devise audit procedures appropriate for detecting SAA's financial management failures; and (3) failures in SAA's internal audit function.

Irregular Award of the Audit

Irregularities were identified in the way PwC/Nkonki had acquired the SAA audit. The Public Audit Act states that if the AG decides not to audit a SOE, the Board of the SOE would be responsible for appointing a private auditor per applicable legislation. Approval by the AG is required to finalize the appointment and to ensure the continuing independence of the auditor. Approval would need to be renewed annually, independent of the length of the tender award. SAA had awarded the audit to PwC/Nkonki, with the awarded contract stating it had been awarded for one year only.8 Yet, SAA did not re-tender the audit following the initial audit year and instead continued to request annual approval from the AG for the reappointment of PwC/Nkonki.

As highlighted in Table 3 (quotes 1 and 2), the AG rationalizes the situation by highlighting imperfections in existing processes (circumstances blaming) and limited knowledge the AG had regarding the duties placed upon the AG by the PFMA in case of audit reappointments (imperfect knowledge). Consistent with the legal requirements at the time, the AG agreed to the re-appointment of PwC/Nkonki for each of the four consecutive years in which these firms continued to audit SAA's accounts. The AG witness at the Zondo Commission states that the AG had given its concurrence to the appointment of the external auditor while knowing that the original audit tender had been for one audit year only. The Commission concluded that because of ‘not particularly well-developed’ processes, the AG had not considered the regularity of SAA's audit appointment process when it concurred with PwC/Nkonki being used as the external auditors (Transcript 20 February 2020, p. 72).

So, in hindsight where I am sitting here to say maybe in those years should we have considered whether maybe they have the public procurement process followed or not, definitely yes. (Transcript 20 February 2020, p. 72)

By emphasizing that the AG's interpretation of the norm has changed over time, the AG witness employs a non-deviation strategy that centres on the refutation, and thus negation, of the espoused norm (Harris, 2022). Their strategy also rests on the justification that it might be reasonable for technical regulatory changes to be overlooked because the AG did not have the benefit of hindsight and perceived its role to be limited at that time (blaming limited role, Table 3, quote 1).

The PwC witness confirmed that the SAA audit was awarded for the 2011/12 year only.9 However, it was their impression the audit award covered five years. The PwC witness relies on imperfect knowledge and inherent ambiguity to support the position.

Firstly, the witness denies responsibility and refers to the fact that he only joined the SAA audit team at PwC from the financial year 2013/14. The auditor was relying on a good faith assumption about the award of the original audit. In the context of imperfect knowledge about how the audit was awarded, the PwC witness maintains that the firm has acted reasonably.

Secondly, the PwC witness employs a fact-nuancing strategy by referring to the existence of an industry practice of appointing auditors generally for five years and, even where they are appointed for one year only, auditors generally continue for five years (Table 3, quote 3). However, when subsequently probed by the Commission on whether this practice applies equally to the private and public sectors, the PwC witness claims he is aware of the practice existing in the private sector but is uncertain as to its relevance in the public sector (Transcript 16 July 2020, p. 85).

A third justification for continuing with the SAA audit following the first audit year is the reliance placed on the concurrence given by the AG (Table 3, quote 4). A type of norm negation approach is followed in terms of which private sector firms deferred to the AG when it came to re-appointments. PwC and Nkonki capitalize on the fact that they are not public sector specialists. This title vests with the AG which, as the supreme audit institute, was assumed to be acting fully within the ambit of the applicable laws, best practices, or other conventions which it would have been instrumental in establishing.

Despite justifications given by the PwC witness, transcripts show that the witness accepts that auditor appointments must include proper procurement processes and that, in the case of SAA, such process had not been followed after the first year. That these requirements are per the PFMA is not disputed. The PwC witness did not accept, however, the Commission's conclusion that, except for the first audit year, the audit fees paid by SAA to PwC/Nkonki would constitute irregular expenditure (Transcript 16 July 2020, p. 96).10 In other words, there are degrees of non-compliance. Certain technical requirements that require specialized knowledge may have been overlooked but the witness maintains that the parties had acted in good faith and according to what they believed was an appropriate process.

Insufficient Audit Scope

PwC and Nkonki failed in their duties as a watchdog institution. Had they performed their functions properly, the shambolic state of financial and risk management in SAA would have been picked up earlier and could have been addressed. It took the intervention of the Auditor General to finally expose these deep deficiencies. (Zondo, 2022, p. 329)

Drawing upon witness statements, we investigate in this section how PwC/Nkonki reflected on their work performed as part of SAA's audit and how this work was commented upon by other stakeholders, including the AG. Initially, in written evidence provided to the Commission, PwC/Nkonki stated that what they had done as part of SAA's audit had been ‘sufficient’ (Transcript 16 July 2020, p. 58). At this point, the audit firm appears to be relying on the fact that auditing standards are extremely technical, principles-based, and dependent on the application of professional judgement. Accordingly, it is difficult for non-experts to identify possible deficiencies and justify a conclusion that the applicable standards were misapplied. In an opaque technical milieu, it is relatively easy to obfuscate and deny any wrongdoing.

However, observations by the AG witness highlighted basic issues which pointed clearly to a departure from the audit standards. Examples included a lack of documentation on how certain account balances had been tested by PwC/Nknonki (see ISA 23011) and PwC/Nkonki not picking up on fundamental failures in SAA's internal control systems, such as the ‘dire’ state of the airline's contract register with its suppliers, which in many cases lacked signed contracts (Transcript 20 February 2020, p. 5) (see ISA 330 and ISA 50012). Faced with clear-cut examples of how PwC/Nkonki did not conduct the audit to the required specifications, the further denial of deviance strategy became unviable. Consequently, when appearing before the Commission, the PwC witness changed their view and admitted to having ‘erred’ (Table 3, quote 5).

This marks a shift from denying responsibility to accepting, at least, some fault to garner sympathy. Realizing that denials may alienate the Commission, the auditors acknowledged the obvious errors flagged by the AG's witnesses, possibly to demonstrate that the auditors are engaging with the evidence being led, are approaching the Commission in an educative way, and are willing to take some remedial action.

Further, the PwC witness emphasizes, as shown in Table 3 (quotes 6 and 7), that despite having issued a clean audit opinion, their firm was dissatisfied with the adequacy of SAA's internal controls and how SAA's Board was attending to issues. By attempting to refine their firm's earlier admission of deviance, the PwC witness displays a fact-nuancing strategy. The auditor accepts responsibility for not ‘elevating’ non-compliance but subtly reminds the Commission that the Board is, ultimately, responsible for SAA's system of internal control. Put simply, the auditor may have missed control deficiencies, but the Board was aware or should have been aware of these and taken appropriate steps, notwithstanding the auditor having ‘erred’.

A similar approach is employed in SAA's annual reports. For example, the Board of Directors acknowledges that the company has not complied fully with provisions of the PFMA dealing with, inter alia, risk management systems and internal controls (Annual Report, 2013, p. 61) but frames the identification of operational and governance challenges as educative. Rather than disputing or disregarding the need for improvement, ‘corrective action was committed to by management’ with Directors emphasizing in the Integrated Report (2013), that material risks were adequately mitigated (Table 3, quote 12).

We considered internal control relevant to our audit of the financial statements, the consolidated annual performance report and compliance with laws and regulations. We did not identify any deficiencies in internal control that we considered sufficiently significant for inclusion in this report. (Annual Report, 2013, pp. 68–69)

Subsequently, possible deficiencies in the SAA external audit are acknowledged during the leading of evidence. The PwC witness gives three explanations for why irregularities identified by the AG were not picked up by the incumbent firms from 2013–2017. Firstly, the witnesses explained that audit firms typically focus on evaluating the validity of financial records in the private sector. The PFMA imposes additional duties when auditing public sector entities, something with which the AG is more experienced (Table 3, quote 9).

This argument blends denial of responsibility with an effort to garner sympathy. PwC and Nkonki mainly service the private sector. That they overlooked material issues at SAA is not because they acted in bad faith but because they do not have the same public sector exposure as the AG. The position relies on the standard of care to which the Commission will hold the auditors. PwC and Nkonki do not need to demonstrate that their audit was as rigorous as one that would have been executed by a public sector expert. To avoid accountability, they must only demonstrate that their work effort was comparable to what would have been done by another audit firm which, like PwC and Nkonki, also had limited public sector experience.

Secondly, the PwC witness claims that in complicated compliance areas such as procurement and contract management, the AG not only has greater expertise but also ‘would like to do a bit more work’ (Table 3, quote 8). In other words, audit firms have differing methodologies and, in conjunction with audits being subject to inherent limitations, one should not expect two auditors to arrive at precisely the same conclusions. This strategy of ‘relativizing’ norms equates to what Henry and Eaton (1999) label deviance neutralization via ‘claims of individualism’.

Thirdly, the PwC witness stresses the complex circumstances under which auditors are operating which limits the nature and extent of the work which can be done during the engagement. The PwC witness also seeks to substantiate this denial of responsibility strategy by emphasizing that auditors have imperfect knowledge about their client, especially when it comes to deliberate concealment of errors, control breakdowns, and misapplication of assets.

Ironically, the neutralization techniques also depend on imperfect knowledge by the evidence leaders and the Commission's Chair. The applicable legislation and the auditing standards require auditors only to undertake engagements which they are competent to perform. Differences in audit methodologies are no excuse for collecting insufficient audit evidence and issuing an incorrect audit opinion (see ISA 330 and ISA 500). Nevertheless, the PwC witness emphasizes how auditing standards are interpreted differently and that the Zondo Commission is dealing with a complex judgemental process rather than blatant non-compliance with auditing prescriptions. In support of this position is that the SAA audit took the AG considerably more time than anticipated. The AG had budgeted 5,500 hours for the audit, including the preparatory stage. By the time it was completed, the engagement took 14,000 hours with SAR14 million (US$820k) in fees unrecovered by the AG.13

Internal Audit Failure

The PFMA (Section 51) requires SOEs to be equipped with a fully capacitated and skilled internal audit body and have appropriate internal controls in place. SAA operated an internal audit department but, as pointed out by the Zondo Commission, it was ‘hopelessly ineffective in identifying or limiting [specified] criminal acts’ (Zondo, 2022, p. 24). An illustration of this is the significant differences between the figures for SAA's irregular expenditure as reported by SAA Management and informed by its internal audit function, versus those discovered by the AG, with an illustration for 2016/17 included in Table 2.

| As reported by: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of expenditure: | SAA management | AGSA |

| Fruitless and wasteful expenditure | 40.4 | 4522.0 |

| Irregular expenditure | 125.9 | 300.7 |

| Total | 166.3 | 4822.7 |

- Source: DD20-PS-1105; AGSA (2017) Management Report South African Airways So Ltd.

Ernst & Young served as SAA's internal auditor until 2011. From 2011/2012, SAA re-established its ‘own in-house internal audit capability’ (Annual Report, 2012, p. 21). It appointed a Chief Audit Executive to head Internal Audit in 2012 (Annual Report, 2012, p. 58). The Audit Committee indicated that it was satisfied with the progress in developing in-house assurance capabilities, the internal audit plan and the overall effectiveness of SAA's control environment in the 2013 (pp. 66–67), 2014 (pp. 87–88), 2015 (pp. 83–84), and 2016 (pp. 68–69) integrated reports.

When the AG took over from PwC/Nkonki as external auditor, it challenged SAA on reported fruitless and wasteful expenditures. Reflecting usual procedures (see ISA 260 and ISA 45014), the AG allowed SAA management to reconsider information included in the financial statements (which are published as part of the annual/integrated reports) on irregular expenditure following additional amounts identified by the AG. SAA's management, however, was unable to do so because of the state of the company's internal administration, which the AG witness described as ‘a mess basically’ (Transcript, 21 February 2020, p. 65).

Shortcomings identified by the Zondo Commission concerning SAA's internal audit function include: (1) a failure to sign contracts following the award of tenders, something which exposed SAA to significant risk; and (2) an extremely poor spare parts record-keeping system making it impossible for AG auditors to verify the existence of many spare parts, including major and highly expensive aircraft components such as jet engines. SAA's poor internal control environment was exacerbated by key executive management positions, including the CEO and CFO being vacant for substantial periods and the Chief Procurement Officer being on suspension. Multiple witnesses indicate that SAA officials lacked appropriate competencies, particularly in the preparation of financial statements, while serious shortcomings existed in the company's IT systems, with important internal documentation lacking or recorded inconsistently, in several cases using handwritten notes.

Failures in SAA's internal audit function are largely explained by witnesses as the result of imperfect capabilities which, according to them, was the outcome of a consistent lack of investment in the internal audit function and a lack of interest by senior management in trying to improve the internal audit capability. The neutralization technique is captured by the maxim ‘you get what you pay for’. The internal auditors cannot reasonably be held accountable when they are expected to oversee and test a complex system of internal controls but (1) lack the necessary resources and (2) are unable to escalate issues because of vacancies on the Board and other challenges.

Further, SAA witnesses frequently use extreme analogies to defend irregularities of SAA's internal procedures and illegal spending. This includes SAA's decision to cancel a multi-million dollar catering contract awarded via a competitive tender to a third party and re-awarding it to a SAA subsidiary (Air Chefs) without tender. The decision was justified by the SAA Board witness by stating that outsourcing would have been like ‘killing a child that was established by SAA’ (Table 3, quote 10), with similar sentiments articulated by a witness from SAA's Audit Risk Committee (Table 3, quote 11). This justification strategy reflects an attempt to negate procurement rules by introducing alternative norms. At the same time, the witnesses use a limited options neutralization. By presenting the decision not to comply with procurement rules as the selection of the ‘lesser of two evils’, the Board member claims SAA avoided what would have been a devasting outcome for the company's subsidiary if procurement rules had been followed.

| Issue | Quote no. | Actor | Quote | Neutralization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irregular award of the audit | 1 | AG witness |

‘we did not, at that time, understand this to be an obligation on us [in case of audit reappointments]’ (Transcript 20 February 2020, p. 74) |

Denial of responsibility: circumstance blaming (blaming limited role) |

| 2 | AG witness |

‘the issue of concurrence has grown or has matured in the organisation’ (Transcript 20 February 2020, p. 72) |

Denial of deviance: norm negation (alternative norms) | |

| 3 | PwC witness | ‘there has never been an environment where we saw an appointment of auditors being done for one year only’ (Transcript 16 July 2020, p. 99) |

Denial of deviance: facts distortion (fact nuancing) | |

| 4 | PwC witness | ‘we took comfort in the fact that the AG gave concurrence and I do know that as part of the concurrence process they [the AG] do ask about the procurement process that was followed’ (Transcript 16 July 2020, p. 100) |

Denial of responsibility: self-hiding (hiding behind imperfect knowledge) | |

| Insufficient audit scope | 5 | PwC witness | ‘Chair, subsequent to the initial statement Chair I did go back. We did go back to the PFMA. We did go back to our records, and we considered what was required of us in terms of the IRBA guide from the office of the general auditor. And Chair, it became clear that we had erred and we should have elevated some of those items of non-compliance Chair to the report’ (Transcript 16 July 2020, p. 58) |

n/a: admission of guilt |

| 6 | PwC witness | ‘We picked up deviations when we performed our work. We informed management. We informed the audit committee [on] the issue with governance, but we did not complete the final step [i.e., informing the shareholder by identifying the matter in the audit opinion]’ (Transcript 16 July 2020, p. 57) |

Denial of deviance: facts distortion (fact nuancing) | |

| 7 | PwC witness | ‘I would not go as far as to say it is a dereliction of duty because we … certainly there are reporting steps that we were able to carry out, Chair’ (Transcript 16 July 2020, p. 65) |

Denial of deviance: facts distortion (fact nuancing) | |

| 8 | PwC witness | ‘The AG ‘would like to do a bit more work’ (Transcript 17 July 2020, p. 43) |

Denial of deviance: norm negation (relativizing norms) | |

| 9 | PwC witness | ‘I reflected on the spirit of the discussions that we had with Mr Sokombela [AG witness] and as I indicated that the office of the AG does this kind of work on a regular continuous basis and that he would certainly want to do much more than what we had performed’ (Transcript 17 July 2020, p. 49) |

Denial of responsibility: self-hiding (hiding behind imperfect capabilities) | |

| Internal audit failure | 10 | SAA Board witness | ‘It does not mean that because it came from a legal department of SAA we must just rubber-stamp and not apply our minds. I would not in my personal capacity opt for killing a subsidiary of SAA and appoint LSG instead of continuing with your own baby’ … In other words, we ought to have killed a child that was established by SAA as a subsidiary. It was not going to be a good decision’ (Transcript 6 November 2020, p. 244) |

Denial of responsibility: circumstance blaming (blaming limited choices) & Denial of deviance: norm negation (alternative norms) |

| 11 | SAA ARC witness | ‘I am saying you hand hold your child. You do not throw your child in the dustbin’ (Transcript 2 November 2020, p. 190) |

Denial of deviance: norm negation (alternative norms) | |

| 12 | SAA integrated report | ‘where internal controls did not operate effectively throughout the year, compensating controls and/or corrective action were implemented to eliminate or reduce the risks. This ensured that the Group's assets were safeguarded and proper accounting records maintained’ (Annual Report 2013, Report of the Audit Committee, p. 64) |

Denial of deviance: facts distortion (fact denial) |

Failures of Board-led Governance Mechanisms at SAA

Ethical and proactive leadership is repeatedly highlighted in SAA's annual reports as a core aspect of SAA's governance and paramount for realizing the company's strategic direction while safeguarding important assets. The Board is supported by suitable sub-committees including, for example, an Audit Committee and a Social and Ethics, Governance and Nominations Committee (e.g., Annual Report, 2012, p. 10). Directors’ biographical information presents a competent and experienced governing body well-suited to ensuring sound financial control, risk management, ethical behaviour and social responsibility. Annual reports further emphasize SAA's focus on compliance with the PFMA and other regulations (Table 4, quote 13). In contrast, the Zondo Commission hears evidence of governance failures and mismanagement. The procurement of goods and services is identified as the main area where material corruption and fraud were taking place in spite of the Board's public statements on the integrity of the company's overall control environment.

| Issue | Quote no. | Actor | Quote | Neutralization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention to ensuring corporate governance quality | 13 | SAA integrated report | ‘the Group executes its compliance obligations with a keen eye on current trends in the global regulatory environment in which SAA operates’ (Annual Report, 2012, Chief Executive's Report, p. 23) | Denial of deviance: facts distortion (fact denial) |

| 14 | AG witness |

‘the members of the Board, it's a crisis mode every day you know … people are in a crisis mode every day, they are meeting the lenders they're meeting the other stakeholder and in as much as SAA is an airline it can't work on autopilot’ (Transcript 21 February 2020, p.117) |

Denial of responsibility: circumstance blaming (blaming limited options) | |

| 15 | AG witness |

‘it becomes a vicious cycle, you know, then unconsciously things then gets neglected, you know and things then they don't work’ (Transcript 21 February 2020, pp. 117-118.) | Denial of responsibility: circumstance blaming (blaming limited options) | |

| 16 | Responsible Minister of Public Enterprises |

‘there was a flurry of allegations and counter allegations making it difficult to make an objective grounded determination as to exactly who [had] failed to fulfil his/her duties’ (Affidavit of Ms Brown dated 23 January 2020, para. 93) |

Denial of responsibility: self-hiding (hiding behind imperfect knowledge) |

|

| 17 | Treasury witness | ‘the implication of not giving SAA a state guarantee would be that auditors would have qualified SAA's financial statements which would have increased the interest rate on SAA’ debt but other SOEs too’ (Audio recording 12 February, 2020) |

Denial of responsibility: circumstance blaming (blaming limited options) |

In 2014, the majority of the Board complained to the then Minister of Public Enterprises about the leadership of the Board's Chairperson (Myeni). Despite this, the Chair (a close friend of then-President Zuma) remained in post until 2017. In terms of transparency, between 2009 and 2012, financial and accounting challenges were found and called the Board's ability to ensure sound strategic direction and control into question. The witness testimonials indicate a steady decline in the quality and effectiveness of governance at SAA from 2012 onwards. The breakdown in corporate governance involves the relationship between the Government (SAA's shareholder and ‘executive authority’ represented by the Minister for the Department of Public Enterprises) and SAA's Board.

The Minister of Public Enterprises at the time (Mr Gigaba) is accused by some witnesses of being over-involved with management and acting as an executive rather than a shareholder. Acute failings in SAA's governance and accountability mechanisms were identified with little monitoring by the Government. In her testimony to the Zondo Commission, former SAA CEO Mzimela described the relationship with Minister Gigaba as lacking an enforced structure with material issues falling ‘through the cracks’ (Transcript 26 June 2019, p. 54).

Concerns about governance failures are echoed by the National Treasury's witness. She highlights a breakdown in the division of roles in SAA, with non-executive directors (NEDs) failing to hold the Board accountable and moderate risky decisions. In relation to the NEDs, between 2009 and 2012 when Carolus was Chair of the Board, there were 11 NEDs but by 2016 the Board had been depleted mostly due to resignations and only four NEDs remained. Matters came to a head in 2016 when the whole Board was replaced to mitigate the harm caused by Myeni, in particular in relation to various transactions including the fall through of a highly lucrative deal for SAA with Emirates and the near failure of a deal which allowed SAA to escape an onerous contract with Airbus. A 2020 court ruling concluded Myeni's actions in relation to the ‘Emirates Deal’ and ‘Airbus Swap Transaction’ were ‘dishonest, reckless and grossly negligent’.15 The Board members raised other issues demonstrating the Chair's deeply unethical manner including intimidation and secret forensic investigations into fellow Board members (Zondo, 2022, p. 46).

In accordance with the prescript of King Code, PFMA and the new Companies Act, the board of directors, through a number of initiatives, has ensured that SAA has a robust and effective corporate governance process in place. This is evidenced by the Boards’ commitment in promoting values of integrity and transparency through the adoption of and compliance with the Company's conflict of interest policies for the Board members and staff members. The SAA's Code of Ethics remains a cornerstone in prescribing the behaviour and conduct of SAA staff in delivering an exceptional service to its customers and other stakeholders.

King IV requires governing bodies to ensure that an effective system of internal control is in place (Principle 15) complemented by an organization-wide culture of ethics (Principle 2) and an overarching commitment to compliance with laws and regulations (Principle 13). The PFMA requires officials to act ‘in the best interest of [a] public entity’ and to take the ‘utmost care to ensure reasonable protection of the assets and records’ of that entity (section 50). These fiduciary duties are echoed by the Companies Act (section 76). SAA's corporate report (see extract above) confirms the importance of these governance principles and statutory responsibilities. The company identifies the King Codes and applicable legislation as integral to how the business is operated and managed. There is a sense of confidence by SAA's executives in the organization's ‘corporate governance processes’ including its Codes of Ethics and overall ability to deliver ‘exceptional services’ to stakeholders. This is completely inconsistent with the Zondo's Commission's conclusion of unethical behaviour, control breakdowns and non-compliance with regulations being widespread and going uncorrected.

The researchers interpret the position presented in the corporate reports as evidence of a type of fact invention strategy being used. SAA constructs the appearance of robust ‘corporate governance processes’ in its official reporting to stakeholders. These stakeholders do not have direct access to the organization's internal operations and the full body of information being reported to senior managers and the governing body. As a result, instances of norm deviations or non-compliance with laws (which are only revealed when evidence is led at the Commission) can be decoupled from the image of an organization committed to the principles of effective governance (per King IV) and the provisions of the PFMA.

Rather than focus the Board's mind on SAA's challenges, witnesses use a state of crisis to excuse the lack of attention paid by Board members to the airline's corporate governance problems (Table 4, quotes 14 and 15). Paradoxically, ongoing financial woes become the justification for the Board's inability to prevent the airline from entering business rescue rather than signalling the need for and driving urgent remedial action. This is a continuation of the ‘lesser of two evils’ argument outlined above. Further, a government minister responsible for supervising SAA uses the justification strategy of having imperfect knowledge, resulting from a ‘flurry of allegations and counter allegations’, making it impossible for him to establish who within SAA is at fault (Table 4, quote 16). In essence, a type of inversion of the norms is being employed where the codes of governance are used to undermine, rather than enable, effective monitoring and control. Best practice per King IV, read with the PFMA and Companies Act, requires Boards with multiple members and supported by various committees comprising executive and non-executive members. Diversity considerations, resource availability, and the need to ensure a balance of power lead to multiple levels of governance. In theory, the outcome is an effective control environment, however, in practice, lines of authority become blurred. When decisions are made by different committees, holding individuals accountable is challenging.

From the National Treasury's perspective, SAA's turnaround plan following the transition of SAA's executive authority from the Minister of Public Enterprises to the Minister of Finance is supported, at least, to some extent. According to witnesses from the Treasury, the Government's options were, however, limited. The airline had become increasingly reliant on government guarantees before SAA's auditors could conclude that the company was a going concern and financial capital providers would continue lending to SAA. The eventual refusal of government guarantees and the subsequent qualification of SAA's audit opinion should have prompted immediate action by the Board but any beneficial effects were offset by worsening the airline's liquidity and solvency problems. When being asked as to why the Treasury provided guarantees for SAA's debt for multiple years and did not put pressure on SAA auditors to qualify SAA's account—something which may have improved governance practices at the airline—the Treasury witness refers to the adverse implications for lender confidence in other South African SOEs and the subsequent increase in the Government's borrowing costs once SAA's accounts would have been qualified (Table 4, quote 17). Hence, circumstance blaming, and particularly limited option rationalizations, appear as the key justification strategy employed by the Government.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Much has been written on corporate governance in the context of developed economies and the causes or consequences of governance failures by large private sector firms. Comparatively little is known about how the public sector deals with governance issues, including the methods employed by implicated parties to neutralize accusations of maladministration. Where current research dealing with governance in SOEs is dominated by quantitative studies of developed economies (Daiser et al., 2017), our study provides a qualitative, case-based analysis of governance and accountability failure in a SOE in an under-researched economy and continent. Data were collected from witness transcripts and other evidence published by the Zondo Commission, SAA's integrated reports, and select media articles. We analyzed these sources to understand how allegations put to auditors and members of SAA's Board of Directors during the Zondo Commission were rationalized.

Testimony that the newly appointed AG required restatements of prior period financial statements, audited by PwC/Nkonki, is not only embarrassing for the professional accountants involved but also calls into question the level of care and skill with which the audit engagements were executed. The Zondo Commission casts doubt on whether the SAA audit was conducted per the applicable standards and relevant regulations. Although auditors cannot detect every error, fraud, or misconduct during an engagement because of inherent limitations, this does not lessen the duty to ensure that testing methodologies were appropriate to conclude on material balances and transactions and that adequate quality control systems were put in place to ensure that SAA's audit was performed to the highest standards.

PwC/Nkonki partly accepted that errors had been made during their audits of SAA, and they offered multiple justifications. Most notable is the actual or perceived willingness by the AG to go beyond what could reasonably be expected as part of an audit engagement of a SOE and the fact that the AG has extensive experience in public sector audits. PwC/Nkonki relied on the complexity of the circumstances and the fact they had imperfect knowledge of SAA to detect material fraud or error. The explanations are a clear example of neutralization techniques mobilized by the auditors to avoid or lessen blame, but they also expose the auditors to further scrutiny. For example, if neither PwC nor Nkonki had the prerequisite experience in public sector audits, why did they accept the SAA engagement in contravention of codes of ethics and the IAS? Further, why did PwC/Nknonki's auditors not qualify their audit reports sooner or request additional resources from their network firms or reach out to the AG for assistance on the SAA audit? PwC/Nkonki led the Zondo Commission to believe their engagements were conducted according to ‘normal’ standards of care while the AG worked to a higher threshold. As the definition of what ‘normal’ standards of care encompasses is partly a result of informal norms and expectations dominant within private audit firms, it proved difficult for the Zondo Commission to validate the extent to which PwC/Nkonki's auditors had deviated from these non-formalized industry norms and practices. However, even if PwC/Nkonki's auditors had not deviated from these norms and expectations, one of the world's largest audit firms with access to significant financial, intellectual, and human resources has conceded publicly that it has been outperformed by a public sector auditor which is a fraction of its size and has a considerably smaller budget than PwC (the world's second-largest accounting firm).

It is tempting to lay the blame for corporate failures on the external auditors but other key parts of the governance system, including government oversight and SAA's internal audit, also failed. Weaknesses in the internal audit function should have heightened PwC/Nkonki's concerns about the overall level of risk of material misstatement at SAA with implications for how the external audits were conducted. At the same time, King IV (Principles 13 and 15) and the PFMA (section 50) require the Board of Directors to take proactive steps to address a significant breakdown in the internal control systems which curtail risk. The Zondo Commission does not conclude on the extent to which SAA's demise is a result of internal or external audit failures but with shortcomings in both formal assurance functions, the probability of material fraud and error going undetected increases significantly.

The Zondo Commission heard testimony on how the Board itself disregarded its fiduciary duties (section 50 of the PFMA and section 76 of the Companies Act). Evidence pointing to mismanagement, negligence, and corruption stands in stark contrast with the position presented in annual reports. The conclusion of the Zondo Commission points to flagrant impression management in corporate reports which relied on information asymmetry to decouple weaknesses in governance mechanisms from the view of the control environment the Board wanted to present to its stakeholders.

To neutralize accusations put to Board members, denial of responsibility, fact distortion, and norm negation are well used. Most notable is the ‘lesser of two evils’ maxim. The Board would have the Zondo Commission believe that departures from codes of best practice and the PFMA were necessary to avoid a calamity. Paradoxically, the Board may never have been in a predicament if the necessary care and skill had been applied to ensure the sound operation of internal control systems and the swift implementation of remedial action when those systems revealed weaknesses or failed.

At the empirical level, this study is among the first to deal concurrently with how an organization and its auditors rationalize non-conformances. Prior studies tend to deal either with management or the auditor (Allini et al., 2016; Ruan and Zhang, 2021) but seldom reflect on how both individuals may be engaged in efforts to circumvent accountability. An added contribution is the source of data. Existing studies on how auditors legitimize themselves in the aftermath of a corporate failure often rely on detailed interviews where respondents cannot be compelled to answer questions (Alleyne and Howard, 2005; Hassan et al., 2023). In contrast, the data for the current study come from evidence led by a commission of enquiry with powers of subpoena and authority to hold witnesses accountable for perjury. As a result, the paper's findings are based on high-quality data which provide better insights than would result from academics engaging with respondents long after studied events and circumstances have transpired.

Further, our article provides one of the first illustrations of neutralization techniques, adapted from deviance theory, and applied in the context of a significant corporate governance failure. Most of the prior literature drawing on deviance theory is found in criminology. There are few examples of how neutralization techniques are mobilized in a commercial context. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to deal concurrently with how neutralization techniques are mobilized in the context of boards of directors justifying weaknesses in internal governance mechanisms and external auditors addressing accusations that their engagements were not performed to the highest standards.

Our analysis of witness testimonials makes a further contribution by demonstrating how individuals’ operationalization of neutralization strategies develops as additional evidence and accusations are put to them. For the auditors, the order in which testimony is given significantly impacts the number of neutralization strategies available. Following evidence of technical and procedural flaws presented by the AG, denying responsibility is no longer a feasible defence strategy for PwC and Nkonki. Both firms changed strategy by acknowledging obvious errors and implementing measures aimed at remedying those shortcomings to garner sympathy. The individuals representing the two audit firms must also take their own and their firm's professional reputation into consideration. This is especially the case for PwC which, unlike Nkonki, is an international firm. Accepting some responsibility for what transpired at SAA may be better than inviting further scrutiny with ramifications for how other audits in South Africa and abroad are being conducted. In contrast, the Board of Directors is less flexible, reflected in the consistent use of denial of responsibility strategies, even as evidence tabled at the Zondo Commission continues to mount. Unlike the auditors, the individual Directors are serving on the SAA Board and run the risk of being declared unfit to serve in that role. Faced with an ‘all or nothing’ situation, the respective Directors hold fast by refusing to accept responsibility irrespective of the evidence presented to them. The two approaches followed by the auditors and Directors, respectively, highlight the importance of incorporating the sequence in which accusations are put to individuals and the context in which those individuals are operating when evaluating how they choose to use neutralization techniques (see Kaptein and Van Helvoort, 2019).

Owing to the many economic and political interests involved, the case of SAA is complex, similar to governance crises at flag carriers and SOEs in other countries (Beria et al., 2011). The complexity, including from a moral angle, was reflected in the decision-making of some individuals we analyzed, including the National Treasury when it sought to balance between its preference to enhance SAA's governance performance versus concerns it had about any increases in South African SOE borrowing costs for taxpayers. This illuminates that in some cases individuals provide genuine justifications for their norm deviation, thereby reflecting a decision-making complexity incorporating unavoidable ethical trade-offs. This decision-making complexity may be genuinely reflected in the retrospective defence lines individuals mobilize. However, with individuals generally portrayed as merely selecting strategies that offer the highest likelihood of avoiding blame, the neutralization framework is at risk of simplifying and emulating an overly cynical approach to human behaviour. This highlights the need to advance the neutralization techniques framework in future studies.

A decision-making complexity is also visible concerning the audit standards where, ignoring cases of obvious norm violation identified by the Zondo Commission, PwC appears to have a different view of what constitutes a ‘good’ audit when compared to the AG. In line with our expectation, leeway in the interpretation of the requirements set by the audit standards increased scope for SAA's auditors to justify behaviour which, even if not in direct violation of those standards, could be construed as inappropriate (Harber et al., 2023). Given their profit orientation, private sector auditors may unavoidably interpret norms differently compared to (not-for-profit) public sector auditors. Sufficiently precise audit standards for auditing public sector organizations with which all auditors need to comply might address this, even though this might cause risks for the commercial attractiveness of public sector audits, which is an issue in several countries (De Widt et al., 2022).

This paper is not without limitations. The demise of SAA is complex and the findings deal with only the use of neutralization techniques deployed by directors, internal auditors, and external auditors called to account by the Zondo Commission. A more refined analysis of exactly how the assurance functions were overcome is required. Future researchers should examine the extent to which internal and external audits were deficient, the professional standards that were not adequately applied, and the facts and circumstances that contributed to any misconduct by professional accountants.