Digital Accountability in Collaborative Public Governance in Times of Crisis: Analysing the Debate in a Polarized Social Forum

Abstract

Accountability in collaborative public governance initiatives and in digital era governance is under-researched, especially in the context of crisis and where issues are debated in a social forum. Accountability considerations are considered particularly important in collaborative governance arrangements, which are of growing relevance for delivering public services. This study, anchored in notions of digital accountability, analyzes debate in a social media forum about a collaborative governance initiative implemented during a crisis. The empirical case is the Austrian contact tracing app, a digital innovation considered key in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. The study makes several contributions. First, it is one of the first to focus on the crucial role of debate in digital accountability in collaborative governance. Second, the study shows that the debate extends beyond the mere content of the innovation, highlighting the need to consider the ‘ecology’ of other (digital) tools, measures, and policies for crisis mitigation in parallel. Third, the study sheds light on the temporal dynamics of accountability in crisis response. The study contributes conceptually to an enhanced understanding of the expertise of actors in delivering and receiving digital public services. It also contributes to a management perspective of digital accountability, which is important given the potential implications for (non)acceptance of public sector innovations in crises and beyond. An enhanced understanding is possibly even more crucial for innovations requiring citizen co-production in sensitive areas such as health.

The COVID-19 pandemic tested the limits of what governments are able to handle. It can be characterized as a transnational mega-crisis with uncertain means-end relationships and unprecedented complexity regarding which values to pursue (Christensen and Lægreid, 2022). As Kornberger et al. (2019) point out, the original meaning of the Greek word krísis derives from krínein, which means both to incise and to decide. A crisis can thus be conceived as a radical interruption that results in a loss of orientation and forces a decision, dividing the flow of events into a ‘before’ and an ‘after’. The pandemic required the making of very big decisions under immense time constraints. A lesson from the pandemic is that governments responding most successfully to the crisis were those that combined management skills with the acceptance of mitigation measures by citizens (Christensen and Lægreid, 2020).

Governments have faced tremendous pressure over the past few decades to tackle increasingly complex social issues with decreasing resources. ‘Collaborative governance’ has been identified as a potential solution to this dual challenge (Ansell and Gash, 2008; Emerson et al., 2011; Triantafillou and Hansen, 2022). In times of crisis, a third challenge arises—the need to act under time pressure. Lægreid and Rykkja (2022) point out that time matters for collaborative arrangements, as these ‘tend to work better when they become more settled and adjusted, and once those involved have come to work better together following more interaction over time and experiential learning’ (p. 17). As there is little time for adjustments during a crisis, potential dysfunctional effects of collaborative governance mechanisms might arise (Jayasinghe et al., 2020). Given this, Lægreid and Rykkja (2022) call for a better understanding of the accountability aspects of collaborative governance arrangements in times of extreme situations. This is echoed by Rinaldi's (2023) study, which highlights the various ‘new big challenges for accounting and accountability studies’ (p. 353) brought about by the mega-crisis that is the COVID-19 pandemic.

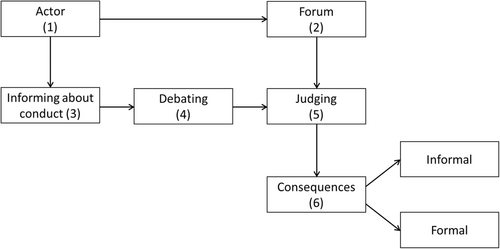

In essence, accountability is a relational concept consisting of six elements (Bovens, 2007). According to t Bovens (2007), ‘[a]ccountability is a relationship between (1) an actor and (2) a forum, in which (3) the actor has an obligation to explain and to justify his or her conduct, (4) the forum can pose questions and (5) pass judgement, and (6) the actor may face consequences’ (p. 450, numbers added). Authors such as Pollitt and Bouckaert (2017) hold that accountability is an antecedent of the acceptance of governmental reforms or innovations by citizens, such as novel digital technologies. Other scholars find that during a crisis, accountability can take on certain nuances that have the potential to result in substantial change and transformation, such as enhancing the acceptance of government recovery actions (Andreaus et al., 2021; Lapsley and Miller, 2019; Leoni et al., 2021; Rinaldi, 2023). Resistance to change is likely if the change is not well understood or not seen as acceptable by those targeted (Hyndman et al., 2019).

The rise of novel digital technologies in recent decades has brought about ‘digital era governance’ as a new governance paradigm that, in essence, focuses on how digital technologies are transforming public governance in a profound manner (Torfing et al., 2020). This manifests on two levels. First, governments have implemented a range of digital public services. Second, the advent of the internet and social media has had repercussions for public accountability, also referred to as ‘digital accountability’ (Agostino et al., 2022b, p. 152). Digital accountability extends, on the one hand, to forms (e.g. discharging of accountability and/or ‘debates’ on social media) (McKee et al., 2011; Schillemans et al., 2013; Vanhommerig and Karré, 2014). On the other hand, with respect to content, Agostino et al. (2022b) hold that accountability is vitally important in contexts where the production and use of data are diffused, such as in collaborative governance. With digital technologies on the rise, a deeper understanding of the relationship between governance and accountability is a pressing issue.

Accountability research, and particularly digital accountability research, however, have so far hardly touched upon collaborative governance. On the contrary, it has been observed that ‘[a]ccountability design has not been a prominent feature in collaborative governance arrangements so far’ (Lægreid and Rykkja, 2022, p. 16). This is surprising, as the literature acknowledges that accountability considerations are particularly important in collaborative governance arrangements (Triantafillou and Hansen, 2022). These arrangements alter the dynamics of ‘traditional’ accountability systems, as a consequence of bringing state and non-state actors together in the service delivery process (Lee, 2022). This change is particularly true with respect to the ‘debate’ element of accountability discharged to a social media forum. According to Bovens (2007, p. 450), a forum ‘can be a specific person, such as a superior, a minister or a journalist, or it can be an agency, such as parliament, a court or the audit office’. Habermas (1984) understands a social forum as a form of ‘public sphere’ facilitating debate. In the context of this paper, we understand social media discussion as an online forum where citizens as participants share their experiences, discuss topics of mutual interest, and ask questions to actors involved in collaborative governance initiatives. Due to the increased complexity of collaboration it might become less clear which actor in the initiative is responsible for delivering what. Moreover, collaborative governance initiatives that deliver digital innovations infuse further novelty into accountability debates.

Also, little is known about the temporal dynamics of digital accountability debates, that is, what shifts in the debate can be observed with respect to covered topics. From these shifts we can obtain insights into the topics that lie at the heart of various periods over the lifespan of, for example, a pandemic mitigation measure delivered collaboratively. Addressing these gaps in the literature, our research questions in this study are: What role does the debate in online fora play in digital accountability in the context of digital public services that are delivered by collaborative governance initiatives during a crisis? What trends can be observed over time?

The empirical focus of the study lies on contact tracing apps (CTAs) as digital public health innovations advocated to play a major role in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic (Whitelaw et al., 2020). ‘Stopp Corona’, the Austrian CTA, was delivered through a collaborative governance arrangement with actors from the non-profit, public, and private sectors. However, the low acceptance of CTAs (as manifested by download and actual use rates) in Western countries left their imagined full potential often unrealized (Zimmermann et al., 2021).

The debate about the CTA is investigated by looking at X (formerly known as Twitter until its rebranding in 2023) as a social media forum. Debates in online fora appear polarized (Hong and Kim, 2016), thus allowing consideration of a broad spectrum of voices. Our case also permits the study of the entire innovation cycle from launch to termination, making insights from a temporal perspective possible.

The study makes several contributions. First, it is one of the first to investigate the still overlooked but crucial roles of debate in the social accountability forum in the context of collaborative governance for pandemic mitigation. With this, a better understanding of the link between accountability mechanisms in digital era governance and the acceptance of (digital) innovations is obtained. Second, the study shows that the debate in social accountability extended beyond the content of the innovation. Other mitigation measures by the government (and even political events beyond COVID-19) had repercussions on the social accountability debate. These results demonstrate that the broader context of crisis management and co-creation aspects are also key to the debate, next to the technical aspects of innovation and the scrutiny of the collaborative governance arrangement within which public services are delivered. Third, the study sheds light on the temporal dynamics in accountability and crisis response. Several dynamics can be identified, illustrating that the accountability debates are not static, but that different topics in digital accountability are prominent over the lifespan of the app.

Moreover, it is imperative to better understand the digital accountability perspective, which foreshadows (non)acceptance of public sector innovations in crises and beyond. The lack of perceived expertise of the lead organization of the consortium with respect to digital technology became a critical issue in the accountability debate. By highlighting the importance (perceived) expertise of actors at the ‘delivering’ and ‘receiving’ end of digital public services in such a situation, the study introduces conceptually the components of expertise to the accountability literature.

CONCEPTUAL ORIENTATION

From Collaborative Governance …

While involving non-state actors in the delivery of public services is not new, such arrangements have received renewed interest in the last decades (Forrer et al., 2010). Ansell and Gash (2008) highlight that decision-making consensus is central to initiatives being regarded as collaborative governance arrangements, in contrast to initiatives where merely the fulfilment of a contract between state and non-state partners is to be achieved. Their study, however, does not focus on citizens as the recipients of the services delivered by collaborative governance initiatives.the processes and structures of public policy decision making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished.

Coordination between governments and their counterparts is primarily structured through formal contracts, written agreements, decision-making procedures, and negotiation regimes. These formal documents include each partner's responsibilities, deliverables, expectations for performance, rewards, and reporting requirements. However, partnership goals are often shifting and fuzzy, making it difficult for partners to estimate what the other partner expects (Lee and Ospina, 2022). According to research, informal mechanisms like long-lasting partnerships, reciprocity, and mutual trust fill the gaps left by formal contractual agreements (Koliba et al., 2011). Functioning partnerships are characterized by mutual respect and influence, a careful balance between synergy and autonomy, and equal participation in decision making and transparency (Forrer et al., 2010).

Taking the lens of accountability, collaborative governance arrangements have been described as polycentric complex networks of multilateral accountability ties, in contrast to a monocentric system of government with a clear chain of command and control (Koliba et al., 2011; Lee and Ospina 2022). In the same vein, Emerson et al. (2011, p. 15) argue that the ‘internal authority structure of collaborative institutions tends to be less hierarchical and stable, and more complex and fluid, than those found in traditional bureaucracies’. Building on these insights, Ansell et al. (2023) recently identified a new role for public bureaucracies, which act like collaborative platforms to facilitate shifting coalitions of actors to come together in purpose-built arenas and then scaffold their interaction. Overall, the literature agrees that collaborative arrangements often lack accountability (Ansell et al., 2023; Koliba et al., 2011).

… To Digital Era Governance

A debate on ‘digital era governance’ has emerged in parallel to the collaborative governance debate (Dunleavy et al., 2006). Digital era governance encompasses three components (Margetts and Dunleavy, 2013). First, to reverse the fragmentation from earlier decentralization measures, ‘reintegration’ is facilitated by joining up and de-siloing public sector processes. As reintegration also stresses the aspect of genuine partnership working between different organizations, it forms a clear link to collaborative governance. A second feature is ‘needs-based holism’, centring on user needs (i.e., creating client-focused structures by redesigning services from a client perspective and putting one-stop processes in place). Third, and most relevant to this study, ‘digitalization’ means adapting the public sector to embrace electronic service delivery wherever possible (Margetts and Dunleavy, 2013). From insights into the diffusion of public sector reform paradigms it is known that ‘new ideas and concepts layer and sediment above the existing ones, rather than replace them’ (Hyndman et al., 2014, p. 388; see also Torfing et al., 2020). With this, collaborative governance is presumably complemented, rather than substituted, by digital era governance.

The understanding of public accountability is also affected by the advent of digital era governance (Schillemans et al., 2013; Vanhommerig and Karré, 2014). Scholars have conceptualized developments in the area as ‘digital accountability’ (Agostino et al., 2022b, p. 152). For example, with respect to the ‘digitalization’ component, there are calls for more research on social media, as they will gain importance in the future for government communication (Torfing et al., 2020). Below, the implications of collaborative governance and digital era governance for public accountability are discussed.

Accountability in Collaborative and Digital Era Governance in Times of Crises

Accountability has conceptual underpinnings in agency theory (Bovens, 2007). Bovens (2007, p. 463) notes that ‘modern representative democracy could be described as a concatenation of principal–agent relationships’. Public accountability has historically largely been about control in the sense of limiting the discretion of governments through compliance with tightly drawn regulations and rules. In essence, government accountability is concerned with maintaining control over non-elected officials (as agents), who are empowered by the delegation of sovereign authority and act in the name of the people and their representatives (as principals; Forrer et al., 2010).

Accountability and collaborative governance

Figure 1 maps the six elements of accountability according to the seminal definition by Bovens (2007). Two elements of his definition deserve particular attention in collaborative governance arrangements, namely the ‘actors’ (1) and the ‘forum’ (2). With respect to the ‘actor’, Bovens (2007) refers to the ‘problem of many hands’, that is, who are the actors. While in traditional public administration, accountability lies with the government as one single actor (as agent) producing a single account, Hansen et al. (2022a) explain that accountability in collaborative governance ‘entails both multiple formats or types of accounts and multiple actors–inside and outside the collaboration–involved in the provision and reception of accounts’. This ‘double multiplicity’ is likely to produce various challenges; for example, the multitude of account-giving formats risks leading to ‘fuzzy accountability’ (Hansen et al., 2022a, p. 1158). In a similar vein, Lee and Ospina (2022) map the accountability components in the transition from bureaucratic to collaborative governance (Table 1). According to the authors, bureaucratic governance focuses on rules, processes, and command-and-control hierarchies. Elected officials make policy decisions, which bureaucrats implement in an efficient way, and accountability relationships between elected officials and bureaucrats is based on a hierarchy of authority. In contrast, Lee and Ospina (2022) find that challenges for accountability in collaborative governance arrangements stem from the shift from a bilateral to a multilateral perspective, requiring consideration of not only vertical but horizontal relationships and a focus on informal and implicit standards. They observe a development from control and audit issues to trust building on the side of the actors (as agents) who are collaborating for service delivery. Nonetheless, Ansell et al. (2022, p. 166; see also Hyndman and McConville, 2018) hold that ‘an accountable cocreation process stands a fair chance of creating a virtuous circle … [H]aving to give accounts can push and help a network or partnership to do better, which will enhance the support from external actors’.

Source: Bovens, 2007, p. 454

| Traditional Public Administration | Market-based Governance | Collaborative Governance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theory base/paradigm | Bureaucracy | New Public Management | Public Value Governance; Networked Community Governance |

| Accountability relationship | Elected official-administrator | Government-private organization | Multilateral relationships between multiple participating organizations |

| ➔ More participants involved; from bilateral to multilateral ➔ | |||

| Attribute of relationship | Hierarchy of authority (vertical) | Principal-agent relationship (vertical) or partnership (horizontal) | Mixed (vertical and horizontal) |

| ➔ Not only vertical relationships but also horizontal relationships ➔ | |||

| Accountability standards | Administrative procedures, regulations, codes of ethics | Contracts, performance measures, mutual trust and durable relationships | Public value, mutual trust and durable relationships, performance measures |

| ➔ Not only formal/explicit standards but also informal/implicit standards ➔ | |||

| Accountability challenges | Bureaucratic control, process standardization, tradeoff between accountability-types | Performance measurement, monitoring and sanctioning, risk sharing | Management of tensions and paradoxes, public value assessment |

| ➔ From trade-offs to paradoxes, from control/audit issues to trust building ➔ | |||

As accountability is a relational concept, a central question concerns the ‘forum’ (2) to which accountability is rendered. Here, Bovens (2007, p. 455) points towards what he refers to as the ‘problem of many eyes’. Similarly, Koliba et al. (2011, p. 211) refer to different ‘accountability frames’. Both studies discuss frames and critical stakeholders for each frame, for example, in political accountability—elected representatives, in legal accountability—courts, in administrative accountability—auditors, in professional accountability—professional peers, in market accountability—shareholders/owners and consumers, and in social accountability—citizens, (associations of) clients, interest groups, charities, and the public at large/civil society. Koliba et al. (2011) propose that collaborative governance arrangements will likely draw on a combination of some or all of the outlined accountability frames, ‘ultimately creating hybrid accountability regimes’ (p. 214). Nevertheless, this might prove difficult in practice, as different accountability frames may collide and place conflicting expectations on the actors in the arrangement, leading to accountability tensions (Lee, 2022). The study by Koliba et al. (2011), a case study of a collaborative governance initiative to mitigate the impact of Hurricane Katrina in the US, illustrates the confusion of project partners as a consequence of multiple accountability frames.

Accountability and digital era governance

We now turn to a discussion of accountability in digital era governance. A recent study by Agostino et al. (2022a, p. 146) argues that ‘[w]hile a lot of attention has been devoted to digital transformation practices, processes, and success factors … far less attention has been devoted to the accounting and accountability implications connected with the adoption and usage of digital technologies in governments’. For example, a study by Bracci (2023) presents a number of applications for artificial intelligence-based decision making by public administrations. He raises the concern that when the underlying algorithm is trained with biased, unreliable, or irrelevant data, the decision could be influenced. Bracci (2023, p. 746) concludes that delegating decisions ‘to a technology, such as calculating a priority list of policy interventions, does not remove the associated responsibility for those tasks’ and further states that such a delegation of decisions ‘could generate responsibility loopholes, widening the accountability gaps’. In turn, he outlines a research agenda for making accountability more ‘intelligent’.

Furthermore, in the digital age, the interactive capabilities of social media have turned communication between actors from a (predominantly) one-way stream to rich interactions, thus making monitoring of government easier and levelling the playing field (Vanhommerig and Karré, 2014). Such ‘digital accountability’ (Agostino et al., 2022b, p. 152) can take new forms (Schillemans et al., 2013) or bring about new roles (Ferry et al., 2022; Vanhommerig and Karré, 2014). With respect to new accountability, research has identified three accountability innovations (Schillemans et al., 2013; Vanhommerig and Karré, 2014): ‘interactive’ (i.e., ‘frequent hearings where the managers of public organizations and their principals collectively identify problems and decide on target areas through interactive discourse’); ‘dynamic’ (i.e., a form of accountability that ‘is based on open data systems that allow citizens and stakeholders to use the data to hold governments accountable’); and ‘citizen-initiated’ forms of accountability (i.e., where ‘the initiative comes from citizens who may also use their own observations and data to summon authorities to action or hold them accountable’) (Schillemans et al., 2013, p. 415). Digital tools enable the continuous scrutiny of initiatives (Ferry et al., 2022), that is, allowing the actions of service providers ‘to be constantly monitored’ (Schillemans et al., 2013, p. 427).

Previous studies also explore how digital technology has altered the role of governments, citizens, audit organizations, and other stakeholders in accountability (Ferry et al., 2022; Vanhommerig and Karré, 2014; see also Bailey and Barley, 2020). For example, new roles for civil society arise when armchair auditing (i.e., auditing at a distance) becomes a possibility (Vanhommerig and Karré, 2014). Furthermore, citizens as co-producers of digital public services also become directly involved in the outcomes of the provided solutions, and they can actively engage in the accountability debate through digital fora such as social media, also exerting new types of pressures on ‘accountors’.

Interestingly, the digital accountability literature identifies similar issues with accountability as are raised in the literature on collaborative governance. Parallel to Bovens’ (2007) identification of ‘problem of many hands’ and ‘problem of many eyes’, Agostino et al. (2022a) identify similar topics in digital accountability and argue that ‘technology-driven changes can enhance accountability toward dialogical and horizontal forms, considering the multicentric structures with several agents and principals’ (p. 146), highlighting that ‘accountability becomes blurred, as are changes in its boundaries’. In particular, digital accountability faces challenges with respect to reliability and quality of digital data of services and how data are selected, analyzed and communicated (ibid.).

Accountability and crises

Concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, prior studies point out that accountability is also crucial in times of crisis (see the special issues edited by Grossi et al., 2020 and Leoni et al., 2021). For example, Andreaus et al. (2021) focus on the account-giving practices by actor(s) during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy and illustrate how different ‘styles of accountability’ are used to communicate with distinct social actors. A review by Rinaldi (2023) reveals that a crisis exposes accountability tensions when there is no clear understanding of the mechanisms that link government action and outcomes, also because measurement is potentially problematic. However, there a research gap remains in relation to the reactions of the forum at the ‘receiving end’ of public services, and further investigation is needed into the collaborative governance arrangements in digital era governance.

To conclude, Table 2 summarizes the previous literature on accountability in collaborative governance with particular attention to the accountability elements as per the definition by Bovens (2007). While a general observation is that there is a growing literature, studies do not concentrate on notions of digital accountability, the debate in the forum, or on (digital) collaborative governance. While much of the previous research acknowledges the importance of the forum to the accountability of collaborative governance initiatives (e.g., Ansell et al., 2022; Jayasinghe et al., 2020; Koliba et al., 2011; Sørensen and Torfing, 2021), in-depth analyses of the forum and dynamics in public accountability are so far missing. Also, recent research by Nerantzidis et al. (2024) reviewing the literature on the use of social media in contemporary accounting research does not find any studies considering digital accountability in collaborative governance in times of crisis. The present study narrows these knowledge gaps in the accountability literature.

| Author(s) | Context of the study | Focus on the element(s) of accountability (Bovens, 2007) |

|---|---|---|

| Ansell et al. (2022) | Development of a model for measuring the accountability of collaborative governance arrangements for achieving SDG goals | All, but only in a prescriptive model |

| Cristofoli et al. (2022) | Conditions under which both accountability and legitimacy occur in collaborative governance | Informing about conduct (3) |

| Hansen et al. (2022a) | Structuring the multiplicity of accountability and legitimacy conceptions in collaborative governance by applying an electoral and a stakeholder logic | Informing about conduct (3) |

| Hansen et al. (2022b) | Accountability relations and challenges of collaborations addressing long-term unemployment in five countries | Role of the client as accountee is investigated (4), but from the view of the actors (1) |

| Jayasinghe et al. (2020) | How accountability in collaborative governance is enacted during crisis | All, but debate (4) in the forum only covered through a community survey |

| Klijn et al. (2022) | Collaboration as necessary and/or sufficient condition for output legitimacy in place branding processes | Informing about conduct (3) |

| Koliba et al. (2011) | Development of a framework for analyzing complex accountability challenges within governing networks with three accountability frames: democratic, market and administrative; Illustration of the breakdown in accountability as well as confusion over trade-offs between accountability frames in a crisis, drawing on the example of Hurricane Katrina |

All, but debate (4) in the forum are not central in the paper |

| Lægreid and Rykkja (2022) | Accountability elements in two collaborative governance arrangements in Norway | Informing about conduct (3) |

| Lee (2022) | Investigating the ways in which participants in collaborative governance experience and manage the conflicting expectations arising from different accountability relationships | Actors (1) |

| Lee and Ospina (2022) | Extending the conceptualization by Bovens (2007) towards a process-based framework for accountability in collaborative governance | All, but only in a prescriptive model |

| Millner and Meyer (2022) | Process of interest and accountability alignment among involved partners over the lifespan of a Social Impact Bond project in Austria | Actors (1) |

| Page (2004) | Analysing the intersection of two types of innovations: accountability for results and interagency collaboration | ‘Interagency Collaboratives’ as emerging actors (1); Informing about conduct (3) |

| Romzek et al. (2014) | Informal accountability mechanisms that facilitate collaboration, joint production, coordination and integration of service delivery, and sustained effort | Actors (1) |

| Sørensen (2012) | Development of a model for measuring the accountability of collaborative innovation | All, but only in a prescriptive model |

| Sørensen and Torfing (2021) | Development of a heuristic framework for analyzing accountability in collective governance; Social accountability as a strategy aiming to improve public sector performance via state–civil society interactions |

All, but only in a prescriptive model; Debate (4) in the forum are regarded as central |

| Triantafillou and Hansen (2022) | Special Issue introduction with two aims:

|

Not explicated |

CASE DESCRIPTION

Despite claims that the COVID-19 pandemic turned out to be an accelerator for the digital transformation of the public sector (Agostino et al., 2020), CTAs as digital public health innovations to mitigate the effects of the pandemic were, in many countries, characterized by a lack of effective participation by the population (Akinbi et al., 2021; Polzer and Goncharenko, 2022). Recent EU-wide data shows that countries’ download ratios varied from about 15-25% to above 50%, while active usage rates (available only for six countries) accentuated that downloads are not fully indicative of active use (European Union, 2022). There is no consensus on what kind of participation rate could be deemed successful in the case of such a unique digital public tool for pandemic mitigation. However, to serve their purpose, CTAs need the active participation of citizens not only through downloading and running the app but also by following the instructions given by the app and reporting once tested positive for COVID-19.

Austria was one of the front-runners in implementing a CTA (‘Stopp Corona’). The app was developed as a collaborative governance initiative between the local chapter of the Red Cross (non-profit organization) leading the innovation, the Federal Ministry of Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection (public sector, financial support), and private sector companies (the insurance company Uniqa with its foundation as major donor and the IT consulting company Accenture as the technical developer). A first functional version was released at the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020. The app's functionalities were consistently improved over time after the initial implementation (ORF, 2020). Citizen participation in the form of participant involvement (Fung, 2006) was limited to the possibility to give feedback on the app and on the source code at a later stage.

The development and release of the contact tracing app by Red Cross Austria was not without its critics. One of the main issues was that this nonprofit organization had ties to the Conservative party in the coalition government at the central level, as its chairman was a former politician running for that party. In Austria, the two major emergency relief organizations have ties to political parties. Samariterbund, the ‘Workers’ Samaritan Federation’, has close links with the Social Democrats, which is the biggest opposition party in the federal parliament (Schmid, 2020). Samariterbund was, for example, involved in delivering vaccinations in Vienna, the largest city that is governed by a coalition government led by the Social Democrats.

However, at the same time, some political actors questioned whether use of the app could lead to potential misuse of gathered data. Other political statements in support of the app also triggered debates, like that of the president of the Austrian federal parliament, a Conservative politician, who suggested the app should be made mandatory. This statement was made about ten days following the launch and later withdrawn due to public pressure.

The hasty launch of the app was in response to the urgent need to implement measures against a rapidly spreading virus. Releasing the first version of the app as quickly as possible and subsequently optimizing the CTA seemed a suitable approach, and the chairman of Red Cross Austria referred to the app as a ‘banana-product’ that matures with the user. There was also no time for an ex ante review by experts. An expert consortium was invited to review the app's closed source code in the first weeks after the launch. Publishing the source code was among several suggestions from the experts, however, overall, their opinion was favourable: ‘The app was clearly developed according to the principle of privacy-by-design and takes the privacy of the users into account. Compared to many other apps on our apps on our phone, there is no location tracking and no advertising’ (Lohninger, 2020, translated by the authors).

Unlike countries such as Singapore or China, the use of the app was voluntary. The project was eventually terminated at the end of February 2022 (despite an ongoing infection wave at that time) when the Ministry of Health as major financial sponsor withdrew (Proschofsky, 2022). Similarly, numerous countries suspended their apps in various stages of 2022 along with the easing of pandemic measures.

METHODOLOGY

Data Collection and Sample

This study focuses on the highly relevant case of CTAs to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. CTAs were regarded as ‘digital helpers that should play a decisive role on the way back to normality after the coronavirus pandemic’ (Amann et al., 2021, p. 11). Given both high expectations of CTAs as a digital tool and the rich constellation of actors involved in delivering CTAs, they provide a curious object of investigation bridging digital accountability and collaborative governance. We are particularly interested in the topics that were debated by the forum and how the debate evolved over time. This research embraces a qualitative research strategy (Patton, 2015), and concentrates on the app's own ‘digital habitat,’ that is, online communication on social media, more specifically on the X platform, following the form of ‘netnography’ (Jeacle, 2021; Kozinets, 2002, 2015). Scholars of accounting and accountability have shown growing interest in utilizing social media for research in the recent decade (Nerantzidis et al., 2024). Social media platforms facilitate human interaction (Bellucci et al., 2019). They constitute speaking arenas that can act as social accountability fora where debates take place (Neu et al., 2019). It has been observed that social media platforms have the potential to overcome the administrative barriers associated with traditional accountability channels (Jeacle and Carter, 2014).

Our research approach can be predominantly described as ‘passive netnography’ (Jeacle, 2021). Netnography was initially developed in marketing research and defined as ‘a new qualitative research methodology that adapts ethnographic research techniques to the study of cultures and communities emerging through computer-mediated communications’ (Kozinets, 2002, p. 62). Passive netnography is the monitoring and observation of archival data, that is, ‘communications and postings of online members made before the researcher enters the community, but which is still available to view’ (Jeacle, 2021, p. 91). It can be differentiated from ‘active netnography’, where the researcher contributes to a continuous real-time conversation, for example, by placing a controversial statement in an online forum as a stimulus to start a discussion. A third form of netnography, that our approach also slightly touches upon, is based on ‘the reflexive field notes produced by researchers themselves during their observation of the online community’ (Jeacle, 2021, p. 92). This was achieved by constant discussion and reflection on the coding process by the researchers, as the coding was done with only a few months delay during the observation period.

Tweets are characterized by their transparency—with being ‘public by default’—and concise statements, as a tweet cannot exceed 280 characters (‘X’—previously called ‘Twitter’, 2022). X is nowadays also regarded as a key communication and public health dissemination tool during outbreak situations, enabling insights into how people respond to certain events and topics such as infectious disease outbreaks, especially during the peak of an event (Ahmed et al., 2019). On the one hand, research has found that data posted on social media sites represents the actual feelings, ideas, and words of a person (Saqib et al., 2023). On the other hand, social media data appears divided. Hong and Kim (2016, p. 777) argue that ‘[t]he “echo chambers” view focuses on the highly fragmented, customized, and niche-oriented aspects of social media and suggests these venues foster greater political polarization of public opinion’. Although X data may not be representative of the whole population, it allows following a sampling strategy that targets maximum variation in gathering data about social opinion (Patton, 2015).

Considering X as a forum for public debate, our focus was on debate amongst citizens over the entire lifespan of the collaborative governance initiative. This type of debate is also particularly interesting in the case of a CTA, as such an innovation requires (data) co-production from citizens (Polzer and Goncharenko, 2022). Multiple search queries on X were performed to collect the data, using combinations of organizational actors involved in the initiative (Austrian Red Cross, Ministry of Health, Uniqa, and Accenture) and the string ‘stopp corona’. Applying and benefitting from the ‘Twitter Academic Access’ scheme (that allowed full archive search delivering 500 tweets per search request) for this study, we collected data in multiple rounds (in intervals of about every month) via the application programming interface (API) of the Postman platform and exported the output to an Excel spreadsheet. In addition, we cross-checked the number of tweets with the search function of ‘tweet count’.

Along with the main text of a tweet, the data collection also included parameters such as user name, full name, date and time of the tweet, and tweet ID. Overall, initially 1,084 tweets were collected. During the analysis, seven tweets that did not relate to the Stopp Corona app were excluded (e.g., when a tweet was a response to a tweet by the Red Cross but commented on an entirely unrelated issue), bringing the total sample down to 1,077 (Table 3). The debate in the ‘forum’ was complemented by the accounts given by the ‘actors’ involved in the consortium. Here, we identified 295 tweets for the period of observation. Table 3 offers a breakdown of the 164 tweets that Red Cross Austria made as the organization that was leading the consortium.

| Temporal brackets | Number of tweets mentioning involved organizational actors* and ‘stopp corona’ | (Number of tweets from Red Cross Austria as leading involved actor with ‘stopp corona’) |

|---|---|---|

(25/03-30/04/2020) |

503 | 47 |

(01/05-30/09/2020) |

368 | 81 |

(01/10-31/12/2020) |

117 | 26 |

(01/01-31/03/2021) |

22 | 3 |

(01/04-31/07/2021) |

16 | 1 |

(01/08-31/12/2021) |

7 | 0 |

(01/01-31/03/2022) |

44 | 6 |

| Total | 1,077 | 164 |

- * majority of tweets mentioning Red Cross Austria as actor.

Regarding forms of digital public accountability investigated, this research sits at the intersection between ‘dynamic’ and ‘citizen-initiated’ forms of accountability (Schillemans et al., 2013, see above). The availability of the app during the two years allowed citizens to engage with and scrutinize the digital tool on an ongoing basis. Both citizens who adopted and tested the app and those who did not download it due to various concerns found the means to express opinions on the online social forum (X). On the one hand, the covered tweets include conversations between actors from the consortium and citizens (dynamic accountability). Here, tweets by lead actors were debated on and replied to. On the other hand, we observed that citizens initiated debates by, for instance, asking questions to lead actors and scrutinizing the app's performance, thus holding the consortium accountable (citizen-initiated accountability).

Coding and Analysis

The tweets were subsequently imported into the Nvivo 1.6.1 software for content analysis. Each tweet forms one unit of analysis. Content analysis was performed manually by the team of two researchers. This approach contrasts studies that use ‘big data’ approaches to analyze debates on social media (e.g., performing automated counting of emotive words or URL link extraction) but that ‘are not particularly well-suited to “deep readings”’ (Neu et al., 2019, p. 45) and grasping the actual meanings of contents.

During the process of coding, following previous research (e.g., Hyndman et al., 2019), positive and negative statements were differentiated, that is, if a tweet took a critical or endorsing stance towards the CTA. For achieving qualitative rigour in the inductive research approach, the coding process was inspired by the method proposed by Gioia et al. (2013), although the themes are not rooted in the exisiting literature. Table 4 provides an overview of the data structure.

| Examples of (first order) concepts | (Second order) themes | Aggregate thematic dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| Technical updates | Functionality | Content |

| Bugs (automatic handshake) | ||

| Meaningful tool | Effectiveness | |

| App will make a difference | ||

| Data protection | Privacy | |

| Anonymity | ||

| Open source | Transparency | |

| Code of backend | ||

| Government surveillance | Fear of misuse | |

| Human rights | ||

| Request to re-launch | Termination | |

| Endorsement of termination | ||

| Credibility of political actors | Credibility of politics | Context |

| Active building of trust | ||

| Vaccination | Pandemic response measures | |

| Mass testing | ||

| Check in at venues | Extension of the business case | |

| Test results on the app | ||

| Interoperability | CTAs of other countries | |

| EU-wide solution | ||

| App in relation to other smartphone apps | Other digital tools | |

| Data sharing with big tech companies | ||

| Debate by the media | Wider debate | |

| Debate about democratic society | ||

| Selection of actors/why these actors | Constellation | Governance of collaboration |

| Coordination between actors | ||

| Commenting on communication | Communication | |

| Requests for clarification | ||

| Cost of app | Budget | |

| Financing gaps | ||

| Reviews by experts | Experts | |

| Calls for experts to be included in the collaboration | ||

| Older citizens | Accessibility | Co-production |

| Language barriers | ||

| Endorsement | Participation | |

| Ticket back to ‘normal life’ | ||

| Citizen-friendly | User centricity | |

| Listen to feedback | ||

| Moral incentive/solidarity | Incentives | |

| Lottery to promote downloads | ||

Initially, in closely paraphrasing the statements in the tweets, first order concepts were defined. A tweet message could contain multiple statements and thus refer to multiple first order concepts. In total, 1,675 codes (859 positive (51%); 816 negative (49%)) were assigned in this step. The results from this coding were 233 positive and 324 negative first order concepts (first column in Table 4). Here, the coding aimed at identifying the debated topics.

Subsequently, the concepts were aggregated into second order themes (20 positive and negative themes each; second column in Table 4). From of these themes, four thematic dimensions (again each positive and negative) were distilled: ‘content’, ‘context’, ‘governance of collaboration’, and ‘co-production’ (third column in Table 4).

In addition, the period of investigation was divided into seven temporal brackets (Langley, 1999). Each bracket was grouping around significant events over the lifespan of the CTA (Table 3). For example, the ‘initial launch and dissemination’ (bracket 1) was differentiated from the ‘discussion about EU interoperability’ (bracket 4), and emerging ‘new/alternative “tickets to freedom”’, such as vaccinations (bracket 5). This bracketing allows the reconstruction of the temporal dynamics in diachronic data.

@roteskreuzat The plan to publish the source code of the app is very welcome (anything else, however, would also be problematic in terms of transparency). Please use an appropriate platform here (e.g. GitHub) that also allows reasonable feedback.

(coded ‘bracket 1’; first order concept ‘opening the source code is a positive move (positive)’ ➔ second order theme ‘transparency (positive)’ ➔ thematic dimension ‘content (positive)’)

Team-coding ensured the accuracy of the coding. Only when both coders agreed on the interpretation of the statement(s) made in a tweet was a concept assigned and included in Nvivo. Such an approach aids in identifying the meanings of the texts beyond merely focusing on expressions and wordings (Kozinets, 2015). The same procedure was followed when aggregating concepts into themes and subsequently into thematic dimensions. The next section presents the insights from the data analysis.The design of the app is built in such a way that it is not suitable for surveillance: According to data protection expert Christof Tschohl, the @roteskreuzat's ‘Stop Corona’ app is not suitable for surveillance.

(coded ‘bracket 1’, first order concept ‘expert view Christoph Tschohl (positive)’ and ‘design-wise not for surveillance (positive)’ ➔ themes ‘experts (positive)’ and ‘fear of misuse (positive)’ ➔ thematic dimensions ‘governance of collaboration (positive)’ and ‘content (positive)’)

FINDINGS

Taking a closer look at the forum to which social accountability is discharged, a polarized debate about the Austrian CTA could indeed be observed. This is evidenced by the distribution of 51% positive versus 49% negative statements.

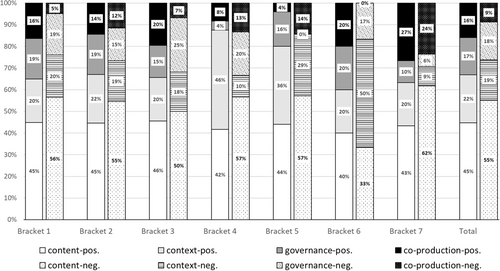

Themes and Thematic Dimensions in the Debate

Overall, the social accountability forum scrutinized not only the immediate content of the ‘CTA as a service’ but also issues that were not directly related to the digital public health innovation. As shown in Figure 2, about half of the coded statements focused on the actual content of the CTA (45% positive and 55% negative). However, this means that the debate also evolved around other thematic dimensions—about one-fifth of statements addressed the wider context of the government's mitigation of the COVID-19 pandemic (22% positive and 19% negative). A further substantial part of the statements (17% positive and 18% negative) focused on governance issues relating to the collaboration initiative. Finally, 16% (9%) of positive (negative) statements related to the co-production of the public service, that is, the engagement of citizens and the potential and encountered barriers in doing so. Interestingly, the differences in the distribution of themes and thematic dimensions that take a positive and a negative stance are not very large from an overall perspective, except for statements endorsing or criticizing the co-production of the digital service.

(source: authors’ own)

Content

The Stop Corona app by @roteskreuzat was further developed and now seems to me—despite all the system-related weaknesses ([e.g.] what the Bluetooth technology is capable of?)—to be a sensible contribution to slowing down the spread of the pandemic. I have now installed the app.

(coded ‘bracket 2’; (second order) theme ‘effectiveness (positive)’)

Interestingly, the initial debates around some topics led to lessons learnt for, and actions of, the accountability holders, such as in the case of the closed source code. Driven by experts and engaged citizens, a clear demand for transparency emerged (publishing the source code). As such, this example demonstrated the dynamic nature of the debate and requests ‘toward improvement, not punishment’ (Schillemans et al., 2013, p. 413). The consortium acted upon this sanction and opened the source code, which was, in turn, welcomed by the social forum. This instance also exhibits a case of ‘learning from accountability’, where the ‘lessons and implications’ can be channelled into the subject of accountability for improvement (Schillemans et al., 2013, p. 414).Thank you @sigi_maurer for the clarifications just now. The app by @roteskreuzat is for protection and not for surveillance. Full stop.

(coded ‘bracket 1’; theme ‘fear of misuse (positive)’)

Context

@roteskreuzat I assume that the Stop Corona app will be expanded by May [2021] to include the functions ‘green pass’ and ‘guest registration’ [in hotels and restaurants]. At the minimum.

(coded ‘bracket 5’; theme ‘extension of business case (positive)’)

@roteskreuzat @rki_de @rudi_anschober Thank you—[it] would increase acceptance and trust in the app if success messages were displayed there—see e.g. German app—the Austrian app has been silent [on my phone] for months.

(coded ‘bracket 2’; theme ‘CTAs of other countries (positive)’)

@lumbric @MartinRadjaby @misik @GFoi @roteskreuzat This is exactly the point. If you take [the other] government [pandemic response] actions seriously, the app is almost obsolete.

(coded ‘bracket 1’; theme ‘pandemic response measures (negative)’)

‘@ClaudiaZettel @katinka_s But Sobotka's statement—even the #schoolyouth of @tiktok_de who don't care, now refuse the app from @roteskreuzat’

(coded ‘bracket 2’; theme ‘debate (negative)’)

Governance of collaboration

@bmsgpk @roteskreuzat Why was this app launched by a non-profit association? Why not by a government authority, i.e. the Ministry of Health?

(coded ‘bracket 3’; theme ‘constellation (negative)’)

Beside directly involved actors’ (i.e. consortium partners) communication, we observed that various indirectly involved political actors also made statements regarding the app, while at the same time, the silence of some relevant public actors was evident. For instance, the city of Vienna only very sparsely endorsed the tracing app on X, while promoting its own pandemic innovation, gargle tests, that became a success story in terms of public uptake.@maxschrems @NOYBeu @epicenter_works @SBA_Research @roteskreuzat Thank you, thank you, thank you! Even as a relatively interested person, I have to rely on experts in this field whom I trust. I am glad about your work!

(coded ‘bracket 1’; theme ‘experts (positive)’)

Is this corona app also available in several languages? I wouldn't have seen anything about it in the app. Not everyone in Austria speaks German. @roteskreuzat

(coded ‘bracket 1’; theme ‘accessibility (negative)’)

In addition, both Red Cross Austria and citizens made attempts to stimulate participation by citizens, as the following statements indicate:Wouldn't the corona app make more sense here? An incentive could be created for downloading and activating the app

(coded ‘bracket 3’, theme ‘incentive (positive)’)

Red Cross Austria: Full transparency: the source code of the Stopp Corona-App is now public https://github.com/austrianredcross #stoppcorona #downloadnow #opensource

(coded ‘bracket 3, theme ‘participation (positive)’)

We continue by analyzing the revealed second order themes and thematic dimensions in terms of their relevance over time.Please download the #StoppCorona App as well, although Franco Foda [the manager of the Austrian national football team was involved in a campaign for promoting the app] is recommending it

(coded ‘bracket 3, theme ‘participation (positive)’)

A Temporal Perspective on Accountability

A second intention of this study is to shed light on how the overall debate on social media evolved over the lifespan of the initiative. As shown by the number of tweets per temporal bracket in Table 3, over 90% of the conversation happened during brackets 1 to 3. This is mirrored by the temporal distribution of tweets on the ‘Stopp Corona’ app by Red Cross Austria as the leading involved actor (Table 3). This section thus focuses on these three first brackets for a meaningful presentation of the calculated percentages from the coded data and to prevent outliers potentially appearing important beyond measure.

Figure 2 presents the distribution of the thematic dimensions and Table 5 shows the distribution of thematic concepts over the temporal brackets. Regarding the former, a relatively stable pattern can be observed over time, with two exceptions: first, looking at the positive and neutral dimensions, issues of co-production seem to have gained nuanced prominence during the third bracket, potentially reflecting frustration due to the second (and long) lockdown in autumn and early winter 2020, which the app did not help to prevent. An interpretation is that the app was potentially regarded as a ‘ticket to freedom’ from this lockdown and thus calls to participate and promotion of the CTA were more intense during bracket 3 than during previous ones. Second, at the same time (especially in comparison with bracket 2), the governance constellation received enhanced scrutiny on the negative side (during the third bracket). An explanation for this could be that during this bracket, disillusionment was possibly starting to form due to the low uptake of the innovation, also spurred by perceived inadequacies in governance constellation and communication efforts by the consortium. This discontent was then voiced in bracket 3 in the accountability debate.

| Second order theme | Bracket 1 | Bracket 2 | Bracket 3 | Brackets 4-7 | Overall weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (positive) | |||||

| Functionality | 11.8% | 26.0% | 24.3% | 20.2% | 21.1% |

| Effectiveness | 10.6% | 10.8% | 17.2% | 13.1% | 12.2% |

| Transparency | 4.1% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 1.2% | 1.5% |

| Privacy | 15.9% | 5.3% | 3.6% | 3.6% | 7.8% |

| Fear of misuse | 2.4% | 1.9% | 0.6% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| Termination | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.6% | 0.3% |

| Context (positive) | |||||

| Credibility of politics | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.6% | 1.2% | 0.3% |

| Pandemic response measures | 4.5% | 6.9% | 8.3% | 4.8% | 6.3% |

| Extension of the business case | 0.4% | 3.0% | 2.4% | 17.9% | 3.6% |

| CTAs of other countries | 0.8% | 8.0% | 5.9% | 7.1% | 5.5% |

| Other digital tools | 4.9% | 1.1% | 1.8% | 0.0% | 2.2% |

| Wider debate | 9.0% | 3.3% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 4.3% |

| Governance (positive) | |||||

| Constellation | 3.7% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 3.6% | 2.1% |

| Communication | 10.6% | 17.2% | 12.4% | 4.8% | 13.2% |

| Budget | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| Experts | 4.1% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 2.4% | 1.6% |

| Co-production (positive) | |||||

| Accessibility | 1.2% | 4.7% | 1.8% | 0.0% | 2.7% |

| Participation | 11.8% | 8.3% | 17.2% | 10.7% | 11.3% |

| User centricity | 3.3% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.3% |

| Incentives | 0.0% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 3.6% | 0.7% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Content (negative) | |||||

| Functionality | 18.7% | 31.6% | 23.9% | 39.0% | 26.0% |

| Effectiveness | 6.1% | 11.2% | 13.6% | 6.5% | 8.8% |

| Transparency | 15.9% | 3.6% | 3.4% | 5.2% | 8.9% |

| Privacy | 7.2% | 7.2% | 4.5% | 1.3% | 6.4% |

| Fear of misuse | 8.6% | 1.0% | 4.5% | 0.0% | 4.5% |

| Termination | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.2% | 0.5% |

| Context (negative) | |||||

| Credibility of politics | 2.9% | 2.0% | 2.3% | 0.0% | 2.2% |

| Pandemic response measures | 4.0% | 3.3% | 3.4% | 2.6% | 3.6% |

| Extension oft he business case | 0.3% | 0.0% | 2.3% | 1.3% | 0.5% |

| CTAs of other countries | 3.7% | 11.5% | 6.8% | 10.4% | 7.6% |

| Other digital tools | 1.4% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.7% |

| Wider debate | 7.2% | 2.0% | 2.3% | 0.0% | 4.0% |

| Governance (negative) | |||||

| Constellation | 11.2% | 4.3% | 10.2% | 9.1% | 8.3% |

| Communication | 4.0% | 8.2% | 13.6% | 1.3% | 6.4% |

| Budget | 0.0% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.5% |

| Experts | 3.7% | 1.6% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 2.3% |

| Co-production (negative) | |||||

| Accessibility | 0.9% | 6.6% | 2.3% | 1.3% | 3.2% |

| Participation | 1.2% | 2.3% | 1.1% | 9.1% | 2.3% |

| User centricity | 0.6% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 5.2% | 1.2% |

| Incentives | 2.3% | 1.6% | 2.3% | 1.3% | 2.0% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Table 5 breaks down the distribution of second-order themes over the temporal brackets (separately for positive and negative statements). The results reveal a number of developments. First, the debate about the app's functionality started on a relatively low level in bracket 1 and then intensified over time. In contrast, during the first bracket, issues such as privacy (positive) and transparency (negative) were of particular concern in the online community. An explanation for this development is that experience with the app had only begun to form and, thus, themes other than functionality were more prominent at the beginning of the initiative.

Second, indicators for this starting formation of experience with the Austrian CTA—and repercussions for the social accountability debate—can be seen at several points. First, bracket 2 brought about more intense examination of the approach of other countries. Here, comparisons of the ‘Stopp Corona’ app were made with CTAs in other countries (both positive and negative), predominantly with its German counterpart (which was a government-led innovation). A second indicator for the accumulation of knowledge with the app relates to the fact that over time, the debate about the potential effectiveness of the innovation intensified, that is, the CTA could play in mitigating the pandemic was better understood from an overall perspective.

Another observation relates to the scrutiny of the actors that were part of the governance constellation. This debate was negatively in tone right from the beginning, except in bracket 2, where less criticism targeted the constellation compared to other themes. This result contrasts communication as a polarized theme. While a substantial number of tweets praised the communication, there was, at the same time, persistently strong criticism. This disapproval of the consortium's communication peaked in bracket 3, possibly fuelled by frustration at the extended lockdown during this temporal bracket and cumulative discontent with the ambiguity of actors’ statements. These observations were evident in tweets referring to, for instance, vague and ambiguous communication by the consortium, including too much noise, as well as critiques about the lack of good marketing of the app when it was needed the most (when pandemic cases and lockdown measures were on the rise).

Overall, a number of temporal dynamics can be identified, illustrating that the accountability debate was not static but embedded in developments in the wider context of the pandemic (and possibly even political events beyond). For instance, the focus of the debate changed when another wave hit due to a further mutation of the virus or experience with the app accumulated. The passage of time allowed users to make cross-references to other countries or to comment on the relationship of digital contact tracing with other measures to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. In the following section, we discuss the findings and outline the implications of the analysis.

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

Contributions

We started this scholarly inquiry with the observation that (digital) accountability in collaborative public governance initiatives (e.g., Hansen and Triantafillou, 2022a; Lægreid and Rykkja, 2022) and digital era governance (e.g., Agostino et al., 2022a; Bracci, 2023) is under-researched. This is particularly the case in the context of crisis and with respect to the ‘debate’ (Bovens, 2007) that takes place in the forum to which accountability is discharged. In addressing these gaps, the study makes several contributions—exploring the understudied digital accountability forum, the themes of the debate, and the evolution of the debate over time. Furthermore, in light of these aspects, the study also contributes conceptually to an enhanced understanding of accountability by introducing the concept of perceived expertise of actors at the ‘delivering’ (i.e., members of the consortium) and ‘receiving’ end (i.e., citizens) of digital public services.

The overlooked debates in digital social accountability fora in collaborative governance

First, connecting a collaborative governance context with a digital era governance context, this study is one of the first to investigate debate in a digital social accountability forum. Although knowledge in the area is building, research is still primarily preoccupied with account-giving practices of actors in collaborative governance. On the other hand, studies addressing the role of the forum in social accountability so far have only focused on non-collaborative settings and non-digital contexts (see the review by Nerantzidis et al., 2024).

With its focus on a digital public health innovation that is collaboratively delivered, our analysis contributes to the understanding of the effects of digital technology on both the form and themes of debate. The digital social forum, X in our case, hosted a dynamic and citizen-led debate (Schillemans et al., 2013). Digital technology not only impacted the ways in which citizens engaged in the accountability debate, but also the voiced themes of accountability. The digital character of the innovation influenced the terms on which the forum regarded actors as responsible and held them accountable. In this respect, the debate in an online forum played an assertive role in calling actors at the delivering end to explain (e.g., justify ambiguous features and behaviours of the app) and act (e.g., improve the app, such as demanding an open-source code).

This study presented a case where the constellation of actors involved in collaborative governance received intense (and often negative) scrutiny in online community debate. One of the reasons for these heavy criticisms might lie in an insufficient understanding by the forum of the roles and responsibilities of each of the consortium actors. Indeed, as collaborative governance initiatives lack clear chains of command and control (Koliba et al., 2011; Lee and Ospina, 2022), from an agency perspective, the ‘problem of many hands’ (Bovens, 2007) becomes a ‘problem of multiple agents’, intensified by the fact that the actors stand on equal footing (Ansell and Gash, 2008).

Many reactions by the online forum indicated that the division and assignment of actors’ roles in the consortium were not clearly communicated and understood, thus constituting an accountability gap (Bracci, 2023). This might be particularly relevant in arrangements that operate in sensitive areas, such as the present one that brings together public health issues and digital co-production as a crisis response.

The debate in the forum extends beyond the CTA as core issue

Second, this study shows that debate in social accountability extends beyond the mere ‘content’ of the innovation. The present study introduces the perspective of the ‘context’ that has so far not received much attention in the accountability literature. For example, users on X constantly debated the value-add of the app vis-à-vis other pandemic mitigation measures (such as lockdowns, the green pass, and vaccinations). Also, the CTA was also compared to non-public social media apps (e.g., Facebook). Overall, how the app interoperated with other pandemic reporting and mitigation initiatives (e.g., from the national health hotline to other countries’ apps) was scrutinized too. With this, questions beyond the app's technical functionality emerged.

Revisiting Lee and Ospina's (2022) four components of accountability in the transition to collaborative governance (Table 1), it can be seen that the debate on X addressed some of these components in the thematic dimension ‘governance of the collaboration’, as the online debate was particularly intense in commenting on the organizational actors involved in delivering the app. Here, many (negative) comments questioned the intentions of the organizations involved in the consortium. For example, the involvement of Uniqa as an insurance company with potential access to health data was viewed very critically.

The forum also voiced general scepticism about political actors and their broader intentions, hinting at the significance of the political dimension in a way that must not be underestimated. It is known from the UK context that political issues unrelated to the pandemic, such as Brexit, overshadowed citizens’ perceptions of the governments’ pandemic response (Smith, 2021). This observation also ties in well with findings from the study of ‘interlinking theorisation’ of new (management) concepts, through co-occurrence with other concepts (Höllerer et al., 2020). This implies that policies and instruments for the mitigation of the pandemic are never evaluated on their own in a vacuum, but in the light of other policies and instruments, related or unrelated to the pandemic. This means that innovations such as CTA are constantly being related to and compared with other pandemic measures, or with the actions of the actors in other areas.

To some extent, the results of this paper also complement some findings of the literature, for example, the review of 61 studies of CTAs by Akinbi et al. (2021). These authors identified the themes ‘privacy concerns’, ‘ethical issues’, ‘security vulnerabilities’, ‘lack of trust’, and ‘technical constraints’ in the reviewed studies, which largely mirror the arguments related to the ‘content’ in the present study, with the difference that ‘privacy’ in our analysis was not only negatively but also positively referred to due to a polarized forum. Additionally, Akinbi et al. (2021) identify the topic ‘user behaviour and participation’ which would relate to the thematic dimension of ‘co-production’ in this study.

The temporal dynamics in accountability and crisis response

Third, the study contributes to the temporal dynamics of the accountability debate, showing that debate was skewed towards the app's launch at the project's beginning. The conversation ebbed away rather quickly, especially from the fourth bracket (beginning in January 2021; Table 3). Still, our analysis (Table 5) demonstrates, for instance, that the relative weight of discourse on the ‘functionality’, as well as on the ‘effectiveness’ of a solution, increased at later stages relative to the initial launch. Also, the voiced fears of potential ‘misuse’ were of relative significance in the initial bracket (upon launch) compared to later stages, where these issues might have been resolved by the responsible actors.

While the phasing out of debate in the social forum indeed can be related to the limited attention span that political initiatives often receive after doubt has been cast on their effectiveness, the number of tweets by the Red Cross as the lead organization fir the CTA substantially decreased over time, too. Although the lead actors, such as the head of the lead organization, still engaged in the citizen-led debate and responded occasionally to comments, the lack of persistent communication indicates that the consortium actors themselves might have lost momentum from an early stage. Here, the literature on change management in the public sector reminds us that although change is known to ebb and flow, ‘momentum needs to be managed with care, not only with regard to a particular change intervention, but also with regard to simultaneous issues and competing priorities’ (Barker et al., 2018, p. 254).

Investigating public accountability from a temporal perspective can also help better understand the formation or non-formation of trust relationships. Hyndman and McConville (2018) find that accountability is ‘an important means of developing, maintaining and restoring trust’ and that accountability and trust can form a ‘virtuous circle’ (p. 227). Although their research focuses on charities, the same can apply to the public sector. Thus, researching the debate in online social accountability fora in the context of a crisis allowed us to obtain important insights for (dis)trust formation and maintenance of collaborative governance arrangements for public service delivery. For example, when consortium actors are unable to dispel suspicion about surveillance by the digital tool right from the beginning, there can be a ‘vicious circle’ of distrust as consequence.

The perceived expertise surrounding the digital crisis response

The literature acknowledges that there are two views on expertise. While a realist view defines the term as ‘real knowledge or the ability to do something’, a constructivist view holds that expertise is viewed as socially attributed perceptions of what other people can do (Kotzee and Smit 2017, p. 646). The analyzed tweets manifest some of these perceptions. Furthermore, there are three basic components of expertise, that is, knowledge, experience, and problem solving (Ericsson, 2018; Herling, 2000).

As discussed in the previous paragraphs, a number of (predominantly negative) perceptions about the actors came to the fore in our data, challenging their expertise on various grounds. Herling (2000) states that expertise is a dynamic rather than static state. Our analysis reveals that the expertise of actors at the ‘delivering’ (i.e., the organizations involved in the consortium) and ‘receiving’ end of the CTA (i.e., citizens co-producing the service by downloading and using the app, requiring digital skills and literacy) was questioned across the whole timespan. Especially, the expertise of Red Cross Austria was seen more in its core business, that is, in rescue management (regarding the components ‘knowledge’ and ‘experience’; Herling, 2000) and not in developing digital technologies. This is surprising, as the expertise of Red Cross Austria lies in emergency response, which could potentially extend to pandemic mitigation. However, the digital character of the tool posed a different ‘context’—outside its main expertise—and by and large deterred a favourable reception in the accountability forum, resulting in a heated debated around actors’ competence.

A similar scepticism was also reflected in debates around the expertise of fellow citizens (as potential users) to co-produce and properly use the contact tracing app. Although there were shifts in the themes of the debate over time, these perceptions did not change.

Limitations and Further Research

As with all empirical studies, the chosen methodological approach has strengths and limitations. With respect to the strengths of analyzing the selected digital social forum, the results from the ‘context’ dimension related to accountability particularly highlighted a large variation of voiced opinions that text genres other than new media are probably unable to grasp. The polarization of the debate on social media (Hong and Kim, 2016) adds to this great variety. Moreover, it can be argued that in studying digital innovations, a research strategy that focuses on X as part of the ‘digital habitat’ of tech-affine persons makes the case also a ‘relevant’ one (Patton, 2015). Issues that the tech-savvy community raises, for example concerning the functionality and accessibility of a digital innovation, most likely apply to other societal groups as well. In addition, the chosen research approach can complement studies that use big data techniques for automated coding (Neu et al., 2019; Nerantzidis et al., 2023) by identifying more nuanced aspects from the empirical material through qualitative coding.

Nevertheless, there are several limitations of the present study that deserve to be mentioned. First, the analyzed debate in online fora is never representative of society overall and thus needs to be complemented by other research approaches. Second, as the analyzed sample is limited, a big data analytics approach could cover much more content, for example, analyzing the comments on newspaper articles.

Questions for further research to address include, for example, how the social accountability debate can be kept alive. In this context, it is relevant to know more about the participating social media users. For example, do most members enter the debate by responding to a tweet issued by the consortium, by re-posting a tweet or do they attempt to start a debate ‘from scratch’? Is it always the same members that respond to tweets by organizational actors? Are members contributing consistently over time or not? Moreover, are there differences in the debate between collaborative governance and other organizational arrangements for pandemic mitigation? Also, as expertise is a dynamic concept (Herling, 2000; Kotzee and Smit, 2016), how is it created, nurtured, and curated, but also destroyed in social accountability? Online fora allow answering these questions and tracing the debate between ‘actor(s) (1)’ and the ‘forum (2)’ (Figure 1), as participants are assigned unique identifiers.

Practical Implications

The results from this research have important implications for practitioners interested in the acceptance of innovations in an era of digital era governance. Often, in the design of digital innovations, the technical is privileged over the social context (Bailey and Barley, 2020). Similarly, Agostino et al. (2022a, p. 150) highlight that digitalization ‘needs to be understood as a holistic process, not just a technological problem, thus requiring a closer look at the behavioural, psychological, ethical and contextual factors involved’. The present study shows that a better understanding of digital technology adoption in the public sector in collaborative governance emerges from a focus on accountability considerations beyond account-giving by organizational actors (Andreaus et al., 2021) and by considering the dynamic debates over time in the forum (see also the recent synthesis by Agostino et al., 2022 on accountability issues in digital transformation). Policymakers should carefully monitor the public opinion that is expressed on social media, possibly in combination with monitoring debates around political accountability and expertise that take place in ‘traditional’ media (see, e.g., the study by Amann et al., 2021, that investigates the discourse around CTAs in newspapers). Here, we also see ample potential to engage with the communication literature (Vásquez, 2022) that, for example, stresses the importance of appropriate communication by governments (e.g., Reynolds et al., 2020), but at the same time considering the reactions at the receiving end of communication. In this context, Lutzky and Kehoe (2022) recently analyzed linguistic changes across time in a large-scale dataset of over 136,000 tweets posted by and addressed to the Irish airline Ryanair between August 2018 and July 2019, using a corpus linguistics approach. Page (2022) highlights that interactions in social media contexts are of multimodal character, that is, include audio-visual resources such as images and videos that represent huge resources for studying digital accountability—for example, when influencers are criticizing the actions of governments.

A second point for policymakers to consider is that the evaluation of the digital innovation does not happen in isolation, but within the ‘ecology’ of other (digital) tools, measures, and policies (Höllerer et al., 2020; Samuel et al., 2021). We suggest that such a relational perspective, that is, looking more holistically at the forum's reaction to pandemic mitigation, can help improve collaborative service delivery and create a ‘virtuous circle’ for such arrangements (Ansell et al., 2022). Such an understanding is possibly particularly important for innovations requiring citizen co-production in sensitive areas such as health.

Furthermore, as shown by the debate extending beyond the mere content of the digital public innovation, transparently showing the role and expertise of leading actors in a collaborative governance arrangement becomes critical to make them accountable. That may at times mean proactively responding to the prospective question, before it emerges, of why and how certain non-obvious actors get involved in the development and implementation of a digital co-production tool.

CONCLUDING REMARKS