Why Do Canadian Firms Cross-list? The Flip Side of the Issue

Abstract

We investigate the relation between managerial incentives and the decision to cross-list by comparing Canadian firms cross-listed on US stock exchanges to industry- and size-matched control firms. After controlling for firm and ownership structure characteristics, we find a positive association between substantial holdings of vested options held by CEOs prior to cross-listing and the decision to cross-list. Further, firms managed by CEOs with substantial holdings of vested options exhibit positive announcement returns and negative post-announcement long-run returns. CEOs of cross-listed firms seem to take advantage of the aforementioned market behaviour, because they abnormally exercise vested options and sell the proceeds during the year of listing only when their firms underperform during the subsequent year. In addition, there is a positive relation between substantial holdings of vested options and discretionary accruals during the year of listing, consistent with the view that CEOs manage earnings to keep stock prices at high levels. Overall, these results have significant implications for the cross-listing literature, suggesting an association between cross-listing and CEO incentives to maximize CEO private benefits.

Globalization continues to fuel cross-listings on the major US and European stock exchanges. Over the past decade, the value of depositary receipts has tripled and depositary receipt trading value has quadrupled, while capital-raising via depositary receipts reached unprecedented levels (Bank of New York, 2011). The increasing interest in cross-listings around the world facilitates a debate among academics and practitioners alike as to why firms cross-list on US stock exchanges. Reasons to cross-list, among others, include firms' desire to benefit from market integration, greater stock liquidity, and improvements in investor protection. 1 Surprisingly, little is known about the relation between decisions to cross-list and managerial incentives. It is possible that cross-listing relates to incentives and opportunities that executives face in response to an increase in the proportion of their wealth tied to equity-based compensation (EBC).

More specifically, the literature identifies links between managerial compensation packages, especially EBC, and strategic decisions, such as mergers (Datta et al., 2001; Grinstein and Hribar, 2004; Minnick et al., 2011), liquidations (Mehran et al., 1998), divestitures (Tehranian et al., 1987), and earnings management/fraud (Gao and Shrieves, 2002; Park and Park, 2004; Johnson et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011; He Huang et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2014). The present study builds on and extends this literature by investigating whether managerial incentives relate to the decision to cross-list. Unlike other managerial decisions, cross-listing is a major discretionary strategic decision that is externally observable. In addition, cross-listing has important implications for shareholder wealth. For instance, Foerster and Karolyi (1999) find that cross-listed firms earn cumulative abnormal returns of 19% for the year preceding listing, and an additional 1.2% in the listing week, but incur a loss of 14% the year following listing. Accordingly, the decision to cross-list presents an ideal setting to explore the relation between managerial incentives and the efficiency of managerial decisions.

We investigate the relation between CEO financial incentives that arise from stock option grants and the decision to cross-list. We divide incentives that arise from stock option grants into short-run incentives and long-run incentives. Short-run incentives are proxied by the intrinsic value of vested stock options held by the CEO, whereas long-run incentives are proxied by both the current value of stock option grants and the intrinsic value of unvested stock options held by the CEO. 2 It is important to differentiate between short-run and long-run incentives, because short-run incentives may motivate maximization of both shareholder wealth and managerial private interests, whereas long-run incentives may motivate only maximization of shareholder wealth. 3 Initially, we establish a relation between financial incentives and the decision to cross-list. Then, we investigate whether CEOs respond to incentives to maximize shareholder value and/or serve managerial private interests.

Our data set consists of Canadian firms cross-listed on US stock exchanges and non-cross-listed Canadian firms matched by industry and size. 4 We first examine the relation between CEO incentives and the likelihood of a cross-listing, controlling for firm characteristics (Pagano et al., 2002) and ownership structure (Doidge et al., 2009). After controlling for growth, profitability, return performance, size, officer ownership, outside director ownership, and CEO ownership, the results show that financial incentives, as proxied by vested options, are positively associated with the probability of a cross-listing in the US, but only to the extent that they are substantial. This relation becomes stronger after excluding growth and return performance controls, suggesting that incentives from EBC to cross-list may be moderated by the presence of growth opportunities. 5

Owing to the ability of CEOs to exercise vested options at any time until expiration, we cannot suggest, ex ante, whether these results are consistent with the view that CEOs respond to incentives to maximize shareholder wealth or to serve managerial private interests. On the one hand, cross-listing enhances a firm's ability to improve financial performance by exploiting growth opportunities, something that would make a CEO's vested options more valuable; on the other hand, a CEO may take advantage of market behaviour around the cross-listing by exercising vested options and selling the proceeds at inflated prices. To shed more light on the aforementioned possible explanations, we investigate (i) the relation between pre-listing vested options with both the market reaction to the cross-listing announcement and the long-run performance of cross-listed firms, (ii) the CEO's vested option exercise behaviour after the listing, and (iii) the relation between pre-listing vested options and earnings management.

Regarding the market reaction to the cross-listing announcement, our results show a positive market reaction, but only to the extent that the CEO of the cross-listed firm has high levels of vested options prior to listing. We also find weak evidence that this relation becomes stronger after excluding growth and return performance controls, suggesting that the market may react more favourably to cross-listing in the presence of growth opportunities. This finding, consistent with Doidge et al. (2004), suggests that a US cross-listing enhances a firm's ability to exploit growth opportunities and rationalizes the propensity to cross-list by CEOs who hold high levels of vested options. In the long run, however, cross-listed firms experience performance that relates inversely to the level of vested options that the CEO holds prior to listing. These results may imply that, in the short run, the market fails to account properly for cross-listing benefits and associated costs, which in turn affects long-run efficient resource allocation in the economy (Mittoo, 2003). Alternatively, the reversal in stock returns may simply represent a decline in firm cost of capital due to market integration, higher liquidity, or higher investor protection (Foerster and Karolyi, 1999; Doidge et al., 2004). Regardless of the reason, this market behaviour may allow CEOs to serve their own private interests using their vested options.

To further explore whether CEOs serve private interests during cross-listing, we investigate CEO vested option exercise behaviour. After controlling for growth opportunities, risk-averse CEO behaviour, psychological factors, and firm size, we document abnormal exercise of vested options and selling of proceeds subsequent to listing by CEOs of cross-listed firms relative to CEOs of control firms. The aforementioned CEO behaviour is observed mainly before the cross-listed firms underperform the control firms over the subsequent year, suggesting that CEOs of cross-listed firms exercise vested options to avoid stock price declines during the subsequent year. 6 Interestingly, we find no abnormal exercise of vested options either in the pre-listing period or in the second year following the listing.

These findings imply that CEOs may have foresight ability regarding subsequent changes in stock prices. This ability is enhanced substantially when certain circumstances, such as earnings management, are present, because earnings management allows managers to exercise some control over the stock price. In this vein, Aggarwal and Cooper (2015) find that managers' desire to sell their stockholdings at inflated prices is a motive for earnings manipulation. Accordingly, we investigate the relation between pre-listing vested options and earnings management. The results show a strong positive relation between substantial holdings of pre-listing vested options and discretionary accruals during the year of cross-listing, consistent with the view that some CEOs may use earnings management to keep stock prices at higher levels. In line with this view, Lang et al. (2006) show that both cross-listed firms reconciling to US GAAP and firms that prepare local accounts in accordance with US GAAP exhibit more evidence of smoothing, a greater tendency to manage towards a target, lower association with the share price, and less timely recognition of losses.

Collectively, these results suggest that the decision to cross-list for firms with CEOs that hold high levels of vested options coincides with a period of high return performance, high levels of discretionary accruals, and is followed by abnormal exercise behaviour of vested options and selling of stocks, primarily before the firm underperforms in subsequent years. We interpret these results consistent with the notion that CEOs of cross-listed firms take advantage of a window of opportunity around the cross-listing; that is, they exercise options and sell the proceeds at inflated prices using private information. A similar behaviour by CEOs is observed around other events, such as secondary offerings and initial public offerings (IPOs). For instance, Maquardt and Wiedman (1998) provide evidence of a greater frequency of voluntary disclosure and a decreased level of information asymmetry when managers sell their stock through a secondary offering. In addition, Aggarwal et al. (2002) find that managers strategically underprice IPOs to maximize personal wealth from selling shares at lockup expiration. Overall, these findings, and our findings on cross-listings, suggest that CEO incentives that arise from EBC relate positively to private benefits.

Background and Motivation

Separation of ownership and control in firms creates information asymmetry problems between shareholders and managers and exposes shareholders to agency risk. In the presence of substantial managerial discretion, it may lead to corporate actions that serve managerial private interests and not shareholder interests (Berle and Means, 1932). One way to align managerial private interests with those of shareholders is through compensation packages (Tirole, 2006). Executive compensation packages may significantly affect managerial decisions, since managers, particularly CEOs, may exert considerable influence on board decisions. The ability of CEOs to affect board decisions arises from the fact that CEOs are likely to possess information that directors do not have, and CEOs determine the board meeting agenda and the information given to the board (see Jensen, 1993; Bebchuk et al., 2002; Bebchuk and Fried, 2003; Krause et al., 2014). 7 As a result, CEOs can influence a possible decision to cross-list.

The equity-based portion of compensation packages is intended to alleviate possible agency problems and to motivate value-maximizing behaviour, because it links managerial compensation to firm performance (Hirshleifer and Suh, 1992; Tirole, 2006). Along this line, prior studies recognize the role of managerial compensation in inducing managers to maximize shareholder wealth in the context of both investment and disinvestment decisions. As far as investment decisions are concerned, Datta et al. (2001) show evidence that CEOs who are paid with high EBC make better acquisitions relative to CEOs paid with low EBC (see also Minnick et al., 2011). With respect to disinvestment decisions, Mehran et al. (1998) document that the likelihood of voluntary liquidation and the resulting enhancement in shareholder wealth increase with the level of CEO EBC. Finally, Tehranian et al. (1987) report a favourable market reaction to voluntary sell-off announcements for firms with long-term performance plans as compared to stock market response for firms without such plans.

However, the wave of corporate scandals in the last two decades has drawn attention to possible flaws in executive compensation practices (Bebchuk and Fried, 2004). While EBC induces greater managerial effort, it also provides incentives to serve managerial private interests, creating a moral hazard problem. Tirole (2006) argues that moral hazard problems manifest in many ways, such as inefficient investments and accounting and market value manipulation. Along this line, prior studies find a relation between earnings management and compensation contract design (Gao and Shrieves, 2002; Bergstresser and Philippon, 2006), earnings management and insider trading (Park and Park, 2004; Beneish et al., 2011; Griffin et al., 2014), fraud/crash risk and compensation (Johnson et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011; Andreou et al., 2016), and mergers and compensation (Grinstein and Hribar, 2004; Fich et al., 2016).

As a result, managerial incentives that arise from EBC significantly affect managerial decisions in a way that either maximizes shareholder wealth or serves managerial private interests. In a similar vein, we suggest that managerial incentives may relate to the decision to cross-list. In particular, prior studies show evidence that cross-listing may improve both the magnitude of growth opportunities and the ability of the firm to exploit future growth opportunities (Miller, 1999; Baker et al., 2002; Pagano et al., 2002; Doidge et al., 2004; Dodd and Louca, 2012). Further, cross-listing enhances the information environment of the firm and reduces the firm cost of equity capital (Coffee, 2002; Lang et al., 2003; Hail and Leuz, 2009; King and Segal, 2009). However, all these factors are determinants of firm value, implying a direct relation between cross-listing and the value of either short-run or long-run financial incentives that arise from EBC. As a result, it is possible that cross-listing may relate to incentives and opportunities that executives may face in response to the proportion of their wealth tied to EBC. Thus, the aim of this study is to examine whether managerial incentives relate to the decision to cross-list, and in such a case, whether CEOs respond to managerial incentives to maximize shareholder wealth and/or serve managerial private interests.

Research Design

Data Set

We investigate the relation between managerial incentives and the decision to cross-list using data for the period 1997–2005. More specifically, the sample consists of Canadian firms that cross-listed their shares on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), NASDAQ, and AMEX during the period 1997–2003. To calculate long-run returns, we use information for the two-year period after cross-listing (i.e., data up to 2005). We hand-collected compensation data from firm annual proxy statements filed with the Ontario Securities Commission and extracted from the System for Electronic Document Analysis and Retrieval (SEDAR). 8, 9 Since SEDAR was launched in 1997, that year is used as the initial cut-off year for our sample. Accounting data were retrieved from the COMPUSTAT database and stock returns from DATASTREAM.

The initial sample consisted of 109 firms that had their first listing on a US major stock exchange. From this sample, we excluded firms with unavailable compensation data. Further, to isolate the pure managerial incentives on the decision to cross-list, we excluded firms with other confounding effects, as follows: (a) 16 firms listed on US and Canadian stock exchanges in the same year; in this case there are two events, initial public offering and cross-listings, which may affect managerial incentives; (b) four firms listed on US exchanges prior to listing in Canada; for these firms, the cross-listing effect in a country with stricter regulations cannot be detected; (c) four firms formed after a merger and listed on US stock exchanges in the same year; for these firms, CEO incentives may be affected by the merger; (d) two firms that changed their fiscal year during the period under investigation, since the periods under investigation are not comparable; (e) five firms that changed CEO during the period tested, since a direct effect of managerial incentives on cross-listing cannot be investigated. 10 These criteria/restrictions led us to a final sample of 64 firms. For this sample, we identified listing and announcement dates through stock exchange websites and through the Lexis/Nexis database. We then collected data from the one-year period prior to the event year to the two-year period following the event. The event year is the fiscal year in which the listing occurred. This procedure yielded a total of 256 firm-year observations.

As a benchmark against which to compare changes in CEO compensation around the cross-listing, we constructed a matched sample. Prior studies find that cross-listed firms exhibit different firm characteristics relative to non-cross-listed firms. Following Charitou et al. (2007), we chose to explicitly match cross-listed firms with non-cross-listed firms based on size and industry. In addition, we implicitly controlled for any other firm characteristics identified by prior studies as cross-listing determinants. Specifically, for each firm cross-listed in a particular year (the year prior to listing), we selected all Canadian non-cross-listed firms for the corresponding year in the same SIC industry code. Among these firms, we selected one matched firm that had the closest amount of total assets compared to cross-listed firms' total assets during the corresponding year. If we did not find firms in the same SIC industry code, we searched for Canadian non-cross-listed firms that belonged in the same three-digit SIC industry code or, alternatively, the same two-digit SIC or one-digit SIC industry codes. Thirty-three firms, or 51.6% of our sample, were matched using a four-digit SIC industry code; eight firms, or 12.5% of the sample, were matched using a three-digit SIC industry code; 14 firms, or 21.9%, were matched using a two-digit SIC industry code; and nine firms, or 14%, were matched using a one-digit SIC industry code.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the cross-listed firms. Panel A presents statistics by year. Generally, we do not observe temporal concentration of sample firms in any particular year; the number of cross-listings ranges from six in 1998 and 1999 (9.4% of the sample) to 11 in 2003 (17.2% of the sample). An exception occurs in 2000, with 17 cross-listings (26.6% of the sample); this year coincides with the last year of the Dot-com bubble. Accordingly, to preclude any bubble effects on our results, we include control variables such as size, growth, and performance, which may correlate with the bubble. Further, it is notable that our main findings remain qualitatively similar when we exclude cross-listings in 2000, alleviating concerns over biased results attributable to the bubble. 11 Panel B classifies the sample based on US cross-listing exchange. Twenty-four firms (37.5%) chose to cross-list on the largest US exchange, NYSE; 20 firms (31.3%) are listed on NASDAQ; and 20 firms (31.3%) are listed on AMEX. The diversity of exchange destination suggests that the exchange itself is not a factor that might affect our results. Panel C sets forth statistics by industry, with cross-listing activity taking place largely within the mining industry (32.8%), the services industry (15.6%), the chemicals industry (10.9%), and the finance, insurance, and real estate industry (9.4%).

| Panel A: Cross-listed firms by year of listing | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Frequency | % |

| 1997 | 7 | 10.9 |

| 1998 | 6 | 9.4 |

| 1999 | 6 | 9.4 |

| 2000 | 17 | 26.6 |

| 2001 | 8 | 12.5 |

| 2002 | 9 | 14.1 |

| 2003 | 11 | 17.2 |

| Total | 64 | 100.0 |

| Panel B: Cross-listed firms by exchange | ||

|---|---|---|

| Exchange | Frequency | % |

| AMEX | 20 | 31.3 |

| NASDAQ | 20 | 31.3 |

| NYSE | 24 | 37.5 |

| Total | 64 | 100.0 |

| Panel C: Cross-listed firms by SIC code | ||

|---|---|---|

| Industry (Two-digit SIC code) | Frequency | % |

| Mining (10–14) | 21 | 32.8 |

| Food and tobacco (20) | 1 | 1.6 |

| Textiles and apparel (23) | 1 | 1.6 |

| Lumber, furniture, paper, and print (25–27) | 3 | 4.7 |

| Chemicals (28) | 7 | 10.9 |

| Petroleum refining (29) | 1 | 1.6 |

| Plastic products (30) | 1 | 1.6 |

| Machinery (35–36) | 4 | 6.3 |

| Games, toys, and children's products (39) | 1 | 1.6 |

| Transport, communications, utilities (40–49) | 6 | 9.4 |

| Wholesale trade (51) | 1 | 1.6 |

| Finance, insurance, real estate (60–69) | 6 | 9.4 |

| Hotels and motels (70) | 1 | 1.6 |

| Services (73–87) | 10 | 15.6 |

| Total | 64 | 100 |

- This table presents descriptive statistics for 64 Canadian cross-listed firms in the US. Panel A presents information for the year of listing. Panel B shows a classification of our sample based on the US exchange used for cross listing. Panel C presents information by industry (two-digit SIC code) for each cross-listed firm.

Empirical Results

Relation between Financial Incentives and the Decision to Cross-list

Compensation and incentive measures for cross-listed and control firms

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for compensation and incentive measures for the year prior to listing. 11 Median cross-listed firm CEO total compensation is C$670,824, which is marginally higher relative to the median value of C$644,754 for control firm CEOs (z = –1.705). Focusing next on the components of total compensation, median salary (bonus) paid by cross-listed firms is C$297,281 (C$99,200), which does not differ statistically from the median of C$250,963 (C$40,000) paid by control firms. However, the median value of new stock option grants for cross-listed firm CEOs is C$131,959, whereas for control firms it is only C$70,360. This difference is statistically significant at the 1% level (z = –6.048), suggesting that CEOs of cross-listed firms receive larger financial incentives in the form of stock option grants.

| Variables | Cross-listed firms | Matched firms | Difference | z-stat./t-stat. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compensation structure | |||||

| Total compensation (000s) | Median | 670,824 | 644,754 | 26,070 | –1.705* |

| Mean | 1,162,468 | 869,654 | 292,814 | 1.850* | |

| Salary (000s) | Median | 297,281 | 250,962 | 46,319 | –0.941 |

| Mean | 370,108 | 414,739 | –44,631 | –0.616 | |

| Bonus (000s) | Median | 99,200 | 40,000 | 59,200 | –0.722 |

| Mean | 241,039 | 198,538 | 42,501 | 0.823 | |

| Option grants value (000s) | Median | 131,959 | 70,360 | 61,599 | –6.048*** |

| Mean | 458,858 | 223,647 | 235,211 | 4.483*** | |

| Incentives from cumulative options | |||||

| Vested options (000s) | Median | 555,982 | 71,917 | 484,065 | –2.515** |

| Mean | 2,193,997 | 2,208,318 | –14,321 | –0.014 | |

| Unvested options (000s) | Median | 97,687 | 0,000 | 97,687 | –1.630 |

| Mean | 1,160,413 | 537,029 | 623,384 | 1.645* | |

| Sample | 64 | 64 | 64 | ||

- This table presents median and mean figures for compensation and incentive measures for cross-listed and control firms and tests for differences between the two groups, for the period prior to the listing. All measures are defined in the appendix. The cross-listed sample consists of 64 firms that entered US stock exchanges in the period 1997–2003. Each cross-listed firm is matched with a control firm that has the closest size (total assets at the end of the fiscal year ended one year before the listing) from among all firms in its industry (SIC codes). The paired sample t-test (two-tailed) and the Wilcoxon signed rank tests (two-tailed) are used to test for the significance of the results. Significance is designated by

- *** at 1%,

- ** at 5%, and

- * at 10%.

Stock option grants, however, have a lockup period in which the CEO cannot exercise the options and sell the proceeds. After the lockup period expires, the CEO may choose to exercise the options at any time until the expiration date. As a result, vested and unvested options may be better measures of financial incentive pay, because they represent cumulative compensation related to both current and past firm performance. The median value of vested options held by the CEOs of cross-listed firms is C$555,982, which greatly exceeds the control firm median value of C$71,917. This difference is both economically meaningful and statistically significant (z = –2.515). At the same time, the median value of unvested options for CEOs of cross-listed firms is C$97,687, which is neither economically different relative to the control firm median value of C$0 nor statistically significant. Thus, the results show that vested rather than unvested options provide greater financial incentives to CEOs of cross-listed firms compared to CEOs of control firms.

Conditional (fixed effects) logistic regression analysis

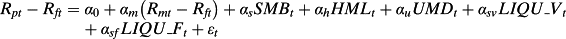

(1)

(1)The dependent variable, CL, is a dummy variable that equals one if the firm is cross-listed, and zero otherwise. We proxy for short-run incentives (SR_Incentives) using the logarithm of one plus the value of vested options (ln(1 + vested options)). Efendi et al. (2007) suggest that managerial incentives increase when managers have substantial holdings of vested options compared to the incentives they have with relatively small holdings of vested options. As a result, managerial incentives arising from vested options may be non-linear. We control for possible non-linearity in managerial incentives by interacting ln(1 + vested options) with a dummy variable that equals one for firms whose CEOs hold above-median vested options, and zero otherwise (P50 * ln(1 + vested options)). 8 Moreover, we proxy for long-run incentives (LR_Incentives) using the logarithm of one plus the value of unvested options (ln(1 + unvested options)) and the logarithm of current option grant value (ln(1 + option grants value)). 9 Finally, consistent with the literature, we explicitly control for factors that may relate to the likelihood of a cross-listing. In particular, we control for differences in firm characteristics, as suggested by Pagano et al. (2002), using the following variables: Book to market, defined as the ratio of book value to market value, Return on equity, defined as the ratio of net income to stockholder equity, Stock returns, defined as annual stock return, and LnTotalAssets, defined as the logarithm of total assets. We also rely on ex-post information about net equity issuance during the year of cross-listing as an ex-ante input that controls for capital-raising needs. In addition, Doidge et al. (2009) suggest that ownership structure in general, and controlling shareholders in particular, relate to the likelihood of a cross-listing decision. Consequently, we also include characteristics of a firm's ownership structure: Outs.Dirs.Own., the percentage of firm stock that outside directors hold at the end of the fiscal year; Officers Own, the percentage of firm stock that officers hold at the end of the fiscal year; and CEO Own, the percentage of firm stock that the CEO holds at the end of the fiscal year. Note that all variables are measured during year –1, except equity issuance, which is measured in the year of cross-listing.

Model 1 in Table 3 presents the results of the likelihood to cross-list using both short-run and long-run incentive variables. The model is highly significant (Wald χ2 = 14.63) and exhibits a relatively high Pseudo R2 (0.345). Moreover, the relation between P50 * ln(1 + vested options) and ln(1 + option grants value) and the likelihood to cross-list is positive and significant (z = 3.14 and z = 2.21, respectively), while the relation between ln(1 + unvested options) and the likelihood to cross-list is statistically insignificant.

| Variables | CL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Short-run incentives | |||

| Ln (1+ Vested Options) | –0.105 | –0.325* | |

| (–1.06) | (–1.89) | ||

| P50 * Ln (1+ Vested Options) | 0.865 *** | 0.906 *** | |

| (3.14) | (3.30) | ||

| Long-run incentives | |||

| Ln (1+ Unvested Options) | 0.035 | 0.074 | |

| (0.42) | (0.43) | ||

| Ln (1 + Option Grants Value) | 0.200 ** | 0.204 | |

| (2.21) | (1.64) | ||

| Firm characteristics | |||

| Book to market | 0.067 | 0.181 | |

| (0.07) | (0.30) | ||

| Return on equity | 1.139 | 0.908 | |

| (1.42) | (1.04) | ||

| Stock returns | 0.682 | 0.195 | |

| (1.33) | (0.77) | ||

| Ln Total assets | 2.951 *** | 4.205 ** | |

| (2.78) | (2.20) | ||

| Equity issuance | 2.378*** | 3.954** | |

| (2.60) | (2.21) | ||

| Ownership structure | |||

| Outs. dirs. Own. | 0.018 | –0.075 | |

| (0.24) | (–0.09) | ||

| Officers own. | –0.026 | –0.006 | |

| (–1.45) | (–0.28) | ||

| CEO own. | 0.001 | –0.006 | |

| (0.14) | (–0.35) | ||

| Wald χ2 | 14.63 *** | 24.79 *** | 35.62 *** |

| Incremental Wald χ2 | 11.89 ** | ||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.345 | 0.585 | 0.735 |

| Sample size | 128 | 128 | 128 |

- This table presents the determinants of the cross-listing decision using conditional (fixed effects) logistic regressions with robust errors. The dependent variable equals one for cross-listed firms, and zero for the control firms. All the variables are defined in the appendix. The cross-listed sample consists of 64 firms that entered US stock exchanges in the period 1997–2003. Each cross-listed firm is matched with a control firm that has the closest size (total assets of the fiscal year ended one year before the listing) from among all firms in its industry (SIC codes). The incremental Wald χ2 tests whether the short-run and long-run incentive variables added in model 3, as a whole, explain a significant portion of the likelihood to cross-list. Significance is designated by

- *** at 1%,

- ** at 5%, and

- * at 10% (in italics below the coefficient).

To benchmark the aforementioned results with a naïve model, we report in model 2 of Table 3 the cross-listing likelihood as a function of firm characteristics (Pagano et al., 2002) and ownership structure variables (Doidge et al., 2009). Interestingly, the significance of the model is larger compared to model 1 (Wald χ2 equals 24.79 vs. 14.63). Moreover, firm characteristics and ownership structure variables explain more variation in cross-listing likelihood compared to short-run and long-run incentive variables (Pseudo R2 equals 0.585 vs. 0.345). With regard to variable attributes, in line with prior literature, firms are more likely to cross-list when they are larger (z = 2.78) and when they have greater need to raise capital (z = 2.60).

Finally, we test for possible interrelations between short-run incentives, long-run incentives, and firm and ownership structure characteristics, by combining them in model 3 of Table 3. Relative to the naïve model 2, the significance of the model, as measured by the Wald χ2, increases substantially from 24.79 to 35.62, whereas the explanatory power of the model, as measured by the pseudo R2, increases from 0.585 to 0.735. With regard to the short-run incentive variables, the likelihood of a cross-listing increases significantly with P50 * ln(1 + vested options) (z = 3.30) but not with ln(1 + vested options) (z = –1.89), suggesting that the magnitude of the vested options holding is important when considering managerial incentives from vested options. For long-run incentive variables, there is no statistically significant relation between both ln(1 + unvested options) and ln(1 + option grants value) and the likelihood to cross-list. Both short-run and long-run incentive variables add significant explanatory power over and above the naïve model (incremental Wald χ2 equals 11.89). Turning to firm characteristics, Book to market, Return on equity, and Stock returns are statistically insignificant, whereas LnTotalAssets and Equity issuance are positively related to the likelihood of a cross-listing (z = 2.20 and z = 2.21, respectively). Finally, we find no relation between the ownership structure variables and the likelihood of cross-listing.

Overall, these results are consistent with the view that substantial holdings of vested options provide incentives to cross-list on US stock exchanges. A potential channel that drives this relation may relate to the fact that US cross-listings enhance a firm's ability to exploit growth opportunities (Doidge et al., 2004). Exploiting growth opportunities also makes substantial holdings of vested options more valuable and, as a result, substantial holdings of vested options in conjunction with growth opportunities should induce cross-listing. To shed more light on this view, we re-estimate model 3 after excluding variables that capture growth opportunities, namely, Book to market and Stock returns. The results show that the coefficient estimate of P50 * ln(1 + vested options) rises from 0.906 to 0.950 (z = 3.30 and z = 3.04, respectively). This finding is consistent with the view that substantial holdings of vested options operate both through growth opportunities and through other channels in inducing cross-listing.

Financial Incentives and Cross-listing Benefits

In this section, we examine the relation between pre-listing vested options and cross-listing benefits. As a proxy for cross-listing benefits, we use both announcement returns and long-run returns.

Announcement returns

(2)

(2)The dependent variable, AR, is the day-zero market-model-adjusted return and the market-adjusted returns in models 1 and 2, respectively. The market-model-adjusted return is estimated using a market model for each firm, and return information from day –150 to day –26 (denoting announcement day as day 0) for cross-listed firms and the national index, as a proxy for the market portfolio. Using this ordinary least squares regression market model, we define market-model-adjusted return as the prediction errors for day 0. Market-adjusted returns are estimated as the difference of the cross-listed firm return and the market return for day 0. As the main independent variable, we include the logarithm of 1 plus the value of vested options (ln(1 + vested options)), which proxies for SR_Incentives. As control variables, consistent with Miller (1999) and Roosenboom and van Dijk (2009), we include several firm characteristics. In particular, we use the following variables: Book to market, defined as the ratio of book value to market value; Return on equity, defined as the ratio of net income to stockholder equity; Stock returns, defined as annual stock return; and LnTotalAssets, defined as the logarithm of total assets.

We estimate the regression model using robust standard errors. Results in Table 4 show a positive relation between short-run incentives and both market-model-adjusted returns and market-adjusted returns. Specifically, both the market-model-adjusted returns and the market-adjusted returns increase significantly with ln(1 + vested options) (t = 2.40 and t = 2.16, respectively). The control variables Book to market and Return on equity are insignificant across all model specifications, whereas Stock returns and LnTotalAssets are generally negatively related to both market-model-adjusted returns and market-adjusted returns. 6

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Market-model-adjusted returns | Market-adjusted returns | |

| Intercept | 0.078 | 0.064 |

| (1.63) | (0.14) | |

| Ln (1+ Vested Options) | 0.006 ** | 0.004 ** |

| (2.40) | (2.16) | |

| Book to market | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| (1.02) | (0.82) | |

| Return on equity | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| (0.27) | (0.21) | |

| Stock returns | –0.006 ** | –0.003 |

| (–2.02) | (–1.17) | |

| Ln Total assets | –0.006 ** | –0.006 * |

| (–1.99) | (–1.72) | |

| No of observations | 64 | 64 |

| F-statistic | 1.78 | 1.31 |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.133 | 0.103 |

- This table presents regression results with robust standard errors of day-0 market-model-adjusted returns and market-adjusted returns on various firm variables. Market-model-adjusted returns are estimated using a market model for each firm. In doing so, we use returns for cross-listed firms and the national index as a proxy for the market portfolio, from day –150 to day –26 (denoting announcement day as day 0). Using this ordinary least squares regression market model, we define cross-listing announcement returns as the prediction errors for day 0. Market-adjusted returns are estimated as the difference in the cross-listed firm return and the market return for day 0. The explanatory variables are as follows: vested options, total assets, book to market, return on equity, and stock returns. All variables are measured during the year prior to the listing and are defined in the appendix. Significance is designated by

- *** at 1%,

- ** at 5%, and

- * at 10%. The t-statistic / z-statistic is in italics below the coefficient estimates.

To gain further insight into the channel that drives the relation between short-run incentives and announcement returns, we re-estimate the results of Table 4 after excluding Book to market and Stock returns. Untabulated results show that when the dependent variable is the market-model-adjusted return, the coefficient estimate of ln(1 + vested options) increases from 0.006 to 0.007 (t = 2.40 and t = 2.56, respectively). Similarly, when the dependent variable is the market-adjusted return, the coefficient estimate of ln(1 + vested options) increases from 0.004 to 0.005 (t = 2.16 and t = 2.25, respectively). These findings may suggest that the market responds more positively to short-run incentives when firms exhibit high growth opportunities. This market behaviour, however, also leads to increases in the wealth of CEOs holding vested options.

Long-run returns

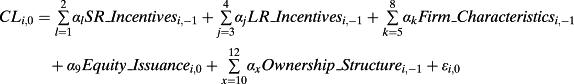

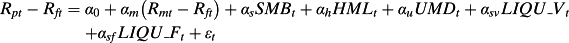

The literature measures long-run abnormal returns using two main approaches: (i) buy-and-hold abnormal returns in excess of the market return or in excess of a single control firm (Barber and Lyon, 1997; Foerster and Karolyi, 2000); and (ii) returns using the calendar-time portfolio approach (Jafee, 1974). Buy-and-hold abnormal returns have been criticized, because this approach may produce biased results due to potential cross-sectional dependence in returns (Fama, 1998). Moreover, buy-and-hold abnormal returns may be affected by possible selection bias that may arise from imperfect matching of the control firms. As a result, we choose to report long-run return results using the calendar-time approach from a US investor perspective (Jafee, 1974). 3 Based on this approach, we compare the one-month excess of the risk-free returns relative to the performance predicted by risk factors. The one-month excess of the risk-free returns is estimated each calendar month as the average monthly excess of the risk-free returns of all firms cross-listed over the preceding 24 months. As risk factors, we use market, size, book-to-market, and momentum, which Fama and French (1993) and Jegadeesh and Titman (1993, 2011) contend explain well the cross-section of stock returns. In addition, Sadka (2006) shows evidence that a variable and a fixed price effect of liquidity are also priced in the cross-section of stock returns. 4 Consequently, if such a six-factor model adequately explains the cross-sectional variation of stock returns, then the monthly abnormal return of cross-listed firms, as measured by the intercept of the model, is expected to be zero under the assumption of no abnormal performance.

(3)

(3)The dependent variable, Rpt – Rft, is the portfolio return measured in US dollars in excess of the risk-free interest rate. The independent variables are the following: excess return on the market, Rmt – Rft; size factor, SMBt, the difference in returns between a portfolio of small and big firms; book-to-market factor, HMLt, the return of a high book-to-market minus the return of a low book-to-market portfolio; momentum factor, UMDt, the return differential between a portfolio of winners and a portfolio of losers; LIQU_Vt, the Sadka variable liquidity factor; and LIQU_Ft, the Sadka fixed price liquidity factor. 5 Consistent with the literature, to reduce the influence of firm-specific return performance, we exclude calendar months with less than six observations in the event portfolio. Moreover, we estimate an average standard error from 1,000 calendar-time portfolio regressions from random portfolios with the same number of observations as the sample portfolios. The test statistic is then estimated as the average intercept divided by the estimated standard error from 1,000 calendar-time portfolios using the six-factor regression model.

Results are presented in Table 5. For the full sample, the intercept is –0.012 (t = –2.31), indicating, consistent with Foerster and Karolyi (1999, 2000), that cross-listed firms underperform after the cross-listing announcement. This finding, however, depends on the level of vested options held by the CEOs prior to the listing. In particular, firms in which CEOs have high levels of vested options exhibit average abnormal returns of –0.014 (t = –1.96) per month over the 24-month period following the cross-listing announcement. In contrast, for firms in which CEOs hold low levels of vested options prior to the listing, abnormal returns are –0.008, but are not statistically different from zero. Consistent with these results, when using adjusted intercepts, that is, the average intercept from the regression of 1,000 random samples of the event portfolios, the results show that the average monthly abnormal return is –0.010 (t = –2.11) for the full sample, –0.013 (t = –1.84) for firms with CEOs that have high levels of vested options, and –0.006 (t = –0.89) for firms with CEOs that have low levels of vested options.

| Variables |

α0 (t-stat.) Implied two-year abnormal return |

Adj. α0 (t-stat.) Implied two-year abnormal return |

Adj. R2 No obs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample (N = 64) | 0.012** | –0.010** | 0.63 |

| (–2.31) | (–2.11) | 90 | |

| –0.252 | –0.214 | ||

| High levels of vested options in year –1 (N = 32) | –0.014** | –0.013* | 0.59 |

| (–1.96) | (–1.84) | 58 | |

| –0.287 | –0.267 | ||

| Low levels of vested options in year –1 (N = 32) | –0.008 | –0.006 | 0.55 |

| (–1.09) | (–0.89) | 68 | |

| –0.175 | –0.134 |

- This table presents regression results with robust standard errors of the following calendar-time portfolio regression:

- The dependent variable is the event portfolio returns measured in US dollars, Rp, in excess of the Treasury bill rate, Rf. Rm – Rf is market return in excess of the Treasury bill rate, SMB is the monthly difference in the returns of a portfolio of small and big firms, HML is the monthly difference in the returns of a portfolio of high book-to-market and low-book-to-market firms, UMD is the momentum factor computed on a monthly basis, as the return differential between a portfolio of winners and a portfolio of losers, LIQU_V is the Sadka variable liquidity factor, and LIQU_F is the Sadka fixed price liquidity factor. These variables are extracted from the website of K. French and WRDS. Given the model, the intercept (α0) measures the monthly abnormal returns. The t-statistic is reported in bold below the coefficient. The adjusted intercept (Adj. α0) is the average intercept from the regression of 1,000 random samples of the event portfolios. The t-statistic is estimated as the Adj. α0 divided by the standard error of the α0 from the calendar-time portfolio regressions. Calendar months with less than six observations in the event portfolio are excluded from the regressions. (N) is the number of firms, and (No obs.) is the number of portfolio events included in the regression analysis. The implied two-year abnormal return is reported below the t-statistic and is computed as [(1 + intercept)24–1].

Collectively, the evidence presented in Tables 4 and 5 suggests that in the short run, the abnormal returns associated with a US listing are positive only to the extent that the CEO of the cross-listed firm has substantial holdings of vested options prior to the listing. Similarly, in the long run, cross-listed firms underperform control firms only to the extent that the CEO of the cross-listed firm has substantial holdings of vested options prior to the listing. This reversal in long-run stock returns may suggest that the market fails to account properly for cross-listing benefits and associated costs, perhaps due to underestimation of US listing costs, such as road shows and public relations (Mittoo, 2003). Alternatively, the reversal in long-run stock returns may represent a decline in a firm's cost of capital due to market integration, higher liquidity, or greater investor protection (Foerster and Karolyi, 1999; Doidge et al., 2004).

CEO Vested Option Exercise Behaviour

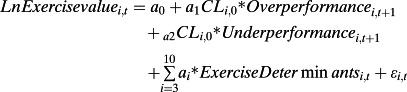

(4)

(4)The dependent variable, Ln Exercise value, is the logarithm of the aggregated value of options exercised by the CEO during the fiscal year. As independent variables, we include CL interacted with Overperformance, and Underperformance. CL is a dummy variable that equals one if the firm is cross-listed, and zero otherwise. Overperformance is a dummy variable that equals one if the cross-listed firm stock returns outperform those of the control firm during the subsequent year. Underperformance is a dummy variable that equals one if the cross-listed firm stock returns underperform those of the control firm during the subsequent year. We suggest that if CEOs have positive private information about a firm's prospects, that is, the firm is underpriced, they should delay the exercise of options, resulting in a lower coefficient for CL * Overperformance. Similarly, if CEOs have negative private information about a firm's prospects, that is, the firm is overpriced, they should increase the exercise of options, resulting in a higher coefficient for CL * Underperformance. 3 Such findings likely indicate the use of private information, and rule out alternative explanations about option exercises, such as exercises triggered by option expiration. 4

We also control for other determinants of option exercises, such as the magnitude of future growth opportunities, using both Book to market, defined as the ratio of book value to market value, and Return on equity, defined as the ratio of net income to stockholder equity. We expect that the higher the growth opportunities, the higher the cost of forfeiting the time value of money, a notion that implies fewer option exercises. Further, similar to Core and Guay (2001), we include Ln Option Grants, defined as the logarithm of options grants, and Ln Vested Options, the logarithm of vested options. Both variables control for the fact that risk-averse CEOs may exercise more options to rebalance their portfolios with higher option grants during the current year. Moreover, Heath et al. (1999) suggest that option exercises relate to psychological factors, such as short-term price trends and reference points with respect to stock price levels. Given the nature of our data (i.e., annual) we cannot control directly for short-term price trends. However, similar to Core and Guay (2001), we control indirectly for the effect of short-term price trends using Stock returns, defined as annual stock returns. In addition, we control for the effect of reference points with respect to stock price levels on options exercises, using 52-week high and 52-week low variables. These variables are defined as the number of months within a given year in which the stock price hits a 52-week high or low, respectively. Each of these variables has a potential range from 0 to 12. Similar to Core and Guay (2001), we suggest that option exercises increase (decrease) when the stock price hits a 52-week high (low). Finally, we include LnTotalAssets, defined as the logarithm of total assets, to control for firm size.

We estimate the regression model using robust standard errors. Results presented in Table 6 show that in both years 0 and +1, the CEOs of cross-listed firms that underperform the control firms during the subsequent year exercise more options relative to CEOs of control firms (t = 3.09 and t = 2.63, respectively). No such evidence exists for CEOs of cross-listed firms that overperform the control firms during the subsequent year. We suggest that the difference in CEO exercise behaviour between cross-listed firms that underperform or overperform the control firms during the subsequent year indicates both the use of private information and the independence of the exercise behaviour from the option expiration problem. Further, based on prior evidence that demonstrates that executives largely sell shares acquired through the exercise of vested options (Ofek and Yermack, 2000), our findings suggest that CEOs of cross-listed firms that underperform the control firms during the subsequent year cash out vested options during the year of cross-listing. Finally, with respect to control variables, depending on model specification, CEOs exercise more options the greater the growth opportunities, the higher the option grants received during the year, the larger the amount of vested options, the lower the number of months in which the stock price hits a 52-week low, and the larger the firm size. Notably, we find no relation between current stock returns and CEO options exercise behaviour.

| Variables | Ln (1 + Exercise value)0 | Ln (1 + Exercise value)+1 | Ln (1 + Exercise value)+2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CL * Overperformance | 0.824 | 0.463 | 0.478 |

| (1.09) | (0.65) | (0.83) | |

| CL * Underperformance | 1.926 *** | 2.073 *** | 0.224 |

| (3.09) | (2.63) | (0.33) | |

| Book-to-market | –0.263 | –0.958 | –0.664 |

| (–1.48) | (–1.62) | (–1.53) | |

| Return on equity | –0.194 | 0.697** | 0.202* |

| (–0.41) | (2.25) | (1.69) | |

| Ln Option grants | 0.177* | 0.153 | 0.034 |

| (1.71) | (1.56) | (0.35) | |

| Ln Vested options | 0.142* | 0.141 | 0.184** |

| (1.66) | (1.55) | (2.04) | |

| Stock returns | –0.126 | –0.289 | –0.199 |

| (–0.45) | (–1.12) | (–0.35) | |

| 52-week high | 0.182 | 0.178 | –0.131 |

| (1.38) | (1.23) | (–0.98) | |

| 52-week low | –0.177 | –0.270* | 0.052 |

| (–1.26) | (–1.84) | (–0.38) | |

| Ln Total assets | 0.032 | –0.055 | 0.189 |

| (0.25) | (–0.41) | (1.55) | |

| Constant | –0.697 | 1.674 | –1.166 |

| (–0.45) | (1.04) | (–0.76) | |

| F-statistic | 4.79*** | 4.84*** | 2.73*** |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.281 | 0.279 | 0.162 |

| Sample size | 128 | 128 | 128 |

- This table presents robust regression results for cross-listed and control firms, on the relation between exercised options, cross-listing, and firm characteristics. All variables are defined in the appendix. The cross-listed sample consists of 64 firms that entered US stock exchanges in the period 1997–2003. Each cross-listed firm is matched with a control firm that has the closest size (total assets at the end of the fiscal year ended one year before the listing) from among all firms in its industry (SIC codes). The numbers in italics are t-statistics for testing the significance of parameter estimates. Significance is designated by

- *** at 1%,

- ** at 5%, and

- * at 10%.

Overall, these results suggest that CEOs exercise vested options abnormally after cross-listing and prior to firm underperformance in subsequent years, possibly by using private information.

Financial Incentives and Earnings Management

In this section, we investigate whether CEOs with large holdings of vested options prior to the listing use discretionary accruals to mislead the market in the short run. In turn, such behaviour would rationalize short-run and long-run performance of cross-listed firms, particularly the abnormal exercise and sale of vested options. Such evidence would confirm and extend the findings of Beneish and Vargus (2002), which suggest that insiders demonstrate abnormal selling of options during periods in which accruals are high, and that such periods are followed by low stock returns.

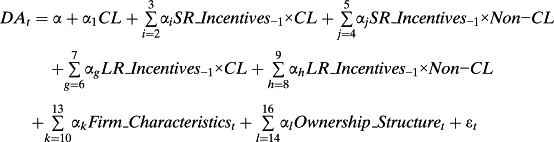

(5)

(5)The dependent variable, DA, represents discretionary accruals from a modified Jones (1991) model. As independent variables, we include CL, which is a dummy variable that equals one if the firm is cross-listed, and zero otherwise. We also include linear and non-linear short-run incentives using ln(1 + vested options) and P50 * ln(1 + vested options) interacted with CL and Non-CL. Non-CL is a dummy variable that equals one for the control firms, and zero otherwise. Similarly, we include long-run incentives using ln(1 + unvested options) and ln(1 + option grants value) interacted with CL and Non-CL. In this respect, the interaction terms with CL reveal the relation between discretionary accruals and short-run incentives / long-run incentives for cross-listed firms, while the interaction terms with Non-CL indicate the relation between discretionary accruals and short-run incentives / long-run incentives for non-cross–listed firms. As control variables, we include firm characteristics, such as Book-to-market, defined as the ratio of book value to market value, Return on equity, defined as the ratio of net income to stockholder equity, Stock returns, defined as annual stock returns, and LnTotalAssets, defined as the logarithm of total assets. Finally, we also control for ownership structure using Outs.Dirs.Own., which is the percentage of firm stock that outside directors hold at the end of the fiscal year, Officers Own, which is the percentage of firm stock that officers hold at the end of the fiscal year, and CEO Own, which is the percentage of firm stock that the CEO holds at the end of the fiscal year.

We estimate the regression model using robust standard errors. Results in Table 7 show that cross-listed firms exhibit fewer discretionary accruals in year 0 relative to control firms, as indicated by the negative and significant CL in year 0 (z = –2.39). Results also show that in year 0 there is a positive and significant relation between discretionary accruals and P50 * ln(1 + vested options) * CL (z = 2.84), suggesting that CEOs of cross-listed firms with substantial holdings of vested options may manage earnings through discretionary accruals, possibly to mislead the market. 1 During the subsequent periods, the relation between discretionary accruals and P50 * ln(1 + vested options) * CL becomes insignificantly different from 0. Interestingly, we find no such relation between discretionary accruals and incentives for the control firms, providing further support for the claim that the aforementioned relation for cross-listed firms is not spurious. 2 Turning to firm characteristics, in year 0, Book to market and Return on equity are negatively related to discretionary accruals (z = –2.01 and z = –3.41, respectively), while Stock returns is positively related to discretionary accruals (z = 1.73). Similar relations exist in years +1 and +2. Finally, we find no relation between the ownership structure variables and discretionary accruals in any year.

| Variables |

Discretionary accruals 0 |

Discretionary accruals +1 | Discretionary accruals +2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept |

–0.229 (–0.44) |

–0.007 (–0.02) |

0.072 (0.46) |

| CL |

–0.504** (–2.39) |

0.220 (1.23) |

–0.011 (–0.14) |

| Short-run incentives | |||

| Ln (1+ Vested Options) * Non-CL | –0.056 (–1.46) | 0.024 (0.73) | 0.010 (0.75) |

| Ln (1+ Vested Options) * CL | 0.046 (1.02) | –0.017 (–0.44) | 0.028* (1.74) |

| P50 * Ln (1+ Vested Options) * Non-CL | –0.041 (1.28) | 0.064** (2.29) | 0.014 (1.27) |

| P50*Ln (1+ Vested Options) * CL | 0.074*** (2.84) | –0.010 (–0.45) | 0.008 (–0.45) |

| Long-run incentives | |||

| Ln (1+ Unvested Options) * Non-CL | 0.013 (0.38) | –0.084*** (–2.77) | –0.015 (–1.21) |

| Ln (1+ Unvested Options) * CL | –0.003 (–0.13) | 0.014 (0.57) | –0.003 (–0.44) |

| Ln (1 + Option Grants Value) * Non-CL | 0.033 (1.11) | 0.014 (0.57) | 0.011 (1.07) |

| Ln (1 + Option Grants Value) * CL | –0.004 (–0.15) | –0.020 (–0.88) | –0.008 (–0.89) |

| Firm characteristics | |||

| Book-to-market | –0.008** (–2.01) | –0.165** (–2.06) | –0.044* (–1.76) |

| Return on equity | –0.661*** (–3.41) | 0.057 (0.76) | –0.036** (–2.17) |

| Stock returns | 0.099* (1.73) | –0.074** (–2.18) | 0.065* (1.74) |

| Ln Total assets |

–0.023 (–0.61) |

–0.007 (–0.21) |

–0.003 (–0.33) |

| Ownership structure | |||

| Outs. dirs. Own. | 0.014 (1.05) | 0.012 (0.94) | –0.002 (–0.38) |

| Officers own. | –0.001 (–0.25) | 0.001 (0.54) | 0.004 (1.25) |

| CEO own. | 0.002 (0.78) | 0.002 (0.79) | 0.000 (0.28) |

| F-statistic | 3.16*** | 1.78** | 1.07 |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| Sample size | 128 | 128 | 128 |

- This table presents the ordinary least squares regression results for cross-listed and control firms, on the relation between discretionary accruals and short-run and long-run incentives measured at year –1, firm characteristics, and ownership structure. All variables are defined in the appendix. The cross-listed sample consists of 64 firms that entered US stock exchanges in the period 1997–2003. Each cross-listed firm is matched with a control firm that has the closest size (total assets at the end of the fiscal year ended one year before the listing) from among all firms in its industry (SIC codes). Significance is designated by

- *** at 1%,

- ** at 5%, and

- * at 10%.

In summary, results suggest that for CEOs who hold high levels of vested options prior to listing, the cross-listing decision coincides with a period of high levels of discretionary accruals.

Robustness Analyses

Our findings link vested options held by CEOs prior to cross-listing with the cross-listing decision, abnormal returns, vested option exercise, and discretionary accruals using disjoint models. To further support the connection between all these variables, we use univariate analysis to compare cross-listed firms with CEOs that hold high levels of vested options prior to listing with those that hold low levels of vested options prior to listing. Results in Table 8 reveal that cross-listed firms with CEOs that hold high levels of vested options exhibit greater market reaction upon the cross-listing announcement, experience more exercising of options during the year of cross-listing and display positive discretionary accruals.

| Variable | Method | High levels of vested options in year –1 | Low levels of vested options in year –1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal market returns | Market-model-adjusted returns |

Mean |

0.025 ** (2.03) |

0.003 (0.43) |

|

Median |

0.006 * (–1.69) |

–0.001 (0.92) |

||

| Market-adjusted returns |

Mean |

0.021* (1.93) |

0.005 (0.74) |

|

|

Median |

0.012* (–1.68) |

–0.000 (0.86) |

||

| Exercise of vested options |

Mean |

931.72 * (0.06) |

89.337** (0.04) |

|

|

Median |

0.000***(0.00) |

0.000*** (0.00) |

||

| Discretionary accruals |

Mean |

0.113** (0.03) |

–0.123* (0.08) |

|

|

Median |

0.032* (0.09) |

–0.076*** (0.01) |

- This table presents median and mean figures for firms with CEOs that hold high- and low-vested options prior to cross-listing. All measures are defined in the appendix. The sample consists of 64 cross-listed firms that entered US stock exchanges in the period 1997–2003. Significance is designated by

- *** at 1%,

- ** at 5%, and

- * at 10%.

We also perform other robustness tests (untabulated results). First, we re-run the results presented in Table 3, controlling for other ownership structure and board composition variables, such as institutional ownership, insider ownership, proportion of independent directors, independence of compensation committee, CEO tenure, and board size. By adding these variables to model 3, the results remain qualitatively similar since none of these variables is statistically significant. Second, to evaluate the importance of possible selection bias problems that may arise from the matched character of the sample, that is, the size effect (Cram et al., 2010), we also employ both linear and quadratic factors of the size variable (Breslov and Day, 1980). Third, we investigate whether industry-matching noise affects the results, since nine out of the 64 sampled firms (14%) are matched using one-SIC industry code. Results presented in model 3 of Table 3 remain qualitatively similar after removing these firms. Fourth, possible selection bias may also affect the results presented in Table 6. To address these concerns, we examine the robustness of the results by comparing the option exercise behaviour of CEOs of cross-listed firms before and after cross-listing, using a fixed effects regression model, a dummy variable (i.e., years –1, +2 vs. years 0, 1) and control variables. In this model, selection bias is expected to be reduced, since each cross-listed firm is used as its own benchmark. Again, the results remain qualitatively similar to those presented above.

Conclusions

We examine (i) whether managerial incentives that arise from EBC relate to the decision to cross-list, and (ii) whether CEOs of cross-listed firms respond to financial incentives to maximize shareholder wealth and/or serve managerial private interests.

Using a sample of Canadian firms cross-listed in the US and an industry–size control sample, we find an association between substantial holdings of vested options and the cross-listing decision, even after controlling for firm characteristics and ownership structure characteristics. We then investigate the sources of the aforementioned association. We document a positive market reaction to the cross-listing announcement, which relates positively to the level of vested options prior to the listing, and a negative relation between vested options and long-run performance. This market behaviour, in conjunction with the documented relation between vested options and the likelihood of a cross-listing, may suggest the presence of private incentives to undertake a cross-listing.

To further investigate whether private incentives drive the decision to cross-list, we examine (i) the behaviour of CEOs with respect to exercise of their vested options after cross-listing, and (ii) the relation between pre-listing vested options and earnings management. Results suggest that for firms with CEOs that hold high levels of vested options prior to the listing, the cross-listing decision coincides with a period of high return performance and high levels of discretionary accruals. Moreover, the cross-listing decision is followed by an abnormal exercise of vested options and sale of stocks before the cross-listed firm underperforms a control firm. Overall, these results have significant implications for the cross-listing literature, suggesting an association between cross-listing and CEO incentives to maximize CEO private benefits.

Despite some limitations related to the relatively small sample size that may affect the generality of the results, narrow jurisdictional scope, and relatively short time interval for the cross-listing decision, our findings are useful to market participants, particularly shareholders, because they are consistent with particular inefficiencies that relate to the way managers are compensated, and they justify recent efforts to ensure proper functioning of corporate boards in publicly traded firms through use of appropriate EBC incentives. The results are also useful to policymakers, such as stock exchange regulators and managers, because they suggest that abnormal option exercises around cross-listing may contain private information, justifying the need for regulators to carry out greater monitoring efforts around option exercises. Finally, these results are useful to academic researchers, because while most empirical studies focus on how cross-listing affects both firms and shareholders, this paper adds a new perspective to the cross-listing literature by providing initial evidence of a relation between managerial incentives and cross-listing.

Appendix

-

- CL

-

- : A dummy variable that equals one if the firm is CROSS-LISTED, and zero for control firms.

-

- Total compensation

-

- : Total annual compensation granted to the CEO, comprising salary, bonus, option grants, restricted stock, long-term incentive payouts, and other annual compensation.

-

- Option grants value

-

- : The value of new stock option grants granted to the CEO, valued using the standard Black–Scholes methodology.

-

- Vested options

-

- : The aggregate dollar amount of options whose lockup period has expired and which the CEO has chosen not to exercise, defined as the year-end stock price minus the exercise price of the options.

-

- P50

-

- : A dummy variable that equals one for cross-listed firms where the CEOs hold vested options above the median value of vested options, and zero otherwise (measured prior to listing).

-

- Outs. dirs. own.

-

- : The percentage of firm stock that outside directors hold at the end of the fiscal year.

-

- Officers own.

-

- : The percentage of firm stock that officers hold at the end of the fiscal year.

-

- CEO own.

-

- : The percentage of firm stock that the CEO holds at the end of the fiscal year.

-

- Total assets

-

- : Total assets at the end of the fiscal year.

-

- Book-to-market

-

- : The book value per share divided by the stock market price at the end of the fiscal year.

-

- Sales growth

-

- : The annual growth in firm sales measured as the difference in the logarithms of annual sales.

-

- Return on equity

-

- : Net income before extraordinary items divided by the book value of equity at the end of the fiscal year.

-

- Stock returns

-

- : The annual stock return measured as the difference in the logarithms of the prices at the end of each fiscal year.

-

- Equity issuance

-

- : The split-adjusted change in shares outstanding times the split-adjusted average stock price, divided by the end of year t–1 total assets.

-

- Rp

-

- : The average monthly calendar return of a portfolio that consists of cross-listed firms that have announced cross-listings in the previous 24 months.

-

- Rf

-

- : The risk-free interest rate.

-

- Rm

-

- : The market portfolio return.

-

- SMB

-

- : The monthly difference in returns of a portfolio of small and big firms.

-

- HML

-

- : The monthly difference in returns of a portfolio of high book-to-market and low-book-market firms.

-

- UMD

-

- : The monthly differential between a portfolio of winners and a portfolio of losers.

-

- LIQU_V

-

- : The Sadka variable liquidity factor.

-

- LIQU_F

-

- : The Sadka fixed price liquidity factor.

-

- Exercise value

-

- : The aggregated value of options exercised by the CEO during the fiscal year. This value is defined as the difference between the market price at the day of the exercise and the exercise price of the options.

-

- Overperformance

-

- : A dummy variable that equals one if the cross-listed firm outperforms the stock returns of the control firm during the subsequent year.

-

- Underperformance

-

- : A dummy variable that equals one if the cross-listed firm underperforms stock returns of the control firm during the subsequent year.

-

- 52-week high

-

- : The number of months within a year that the stock price hits a 52 week high. This variable has a potential range from 0 to 12.

-

- 52-week low

-

- : The number of months within a year that the stock price hits a 52 week low. This variable has a potential range from 0 to 12.

-

- DA

-

- : Discretionary accruals estimated from a modified Jones (1991) model. Specifically, for each year and industry classification based on Fama and French (2007), we estimate the following model:

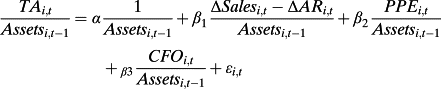

where TAi,t is the change in current assets plus the change in debt in current liabilities and the change in income tax payable minus the change in current liabilities, and the change in cash and depreciation and amortization expenses. Assetsi,t is total assets. ΔSalesi,t is the change in sales. ΔARi,t is the change in accounts receivable. PPEi,t is property, plant, and equipment. CFOi,t is cash flow from operations after excluding extraordinary items. -5 Discretionary accruals are the residuals of the model.

- : Discretionary accruals estimated from a modified Jones (1991) model. Specifically, for each year and industry classification based on Fama and French (2007), we estimate the following model:

References

- 1 Karolyi (2006) and Benos and Weisbach (2004) provide a useful review of the cross-listing literature.

- 2 Similar to Efendi et al. (2007), we use intrinsic stock option values, rather than the sensitivity of the CEO's options holdings to stock price changes (Core and Guay, 2002), because intrinsic stock option values capture information on both possible equity overvaluation and CEO option price sensitivity.

- 3 Short-run incentives (vested options) refer to those options with an expired lockup period that the CEO chooses not to exercise. Conversely, long-run incentives (unvested options) refer to those options with an unexpired lockup period. Thus, vested options may justify either value-maximizing behaviour or managerial private interest behaviour, because they can be exercised at any time until the expiration date, whereas unvested options justify only value-maximizing behaviour, because they cannot be exercised in the short run even if they are deep in-the-money.

- 4 We use Canadian cross-listed firms on US stock exchanges because Canadian firms have a long tradition of listing in the US and make up the single largest group of foreign firms listed on US stock exchanges. As a result, we ensure a satisfactory sample of firms that operate within the same institutional framework.

- 5 Throughout the study, we refer to an association between vested options and cross-listing, without reference to causality. The reason for this is that we cannot rule out the possibility that both vested options and cross-listing are associated with a third unobservable factor that may lead to a spurious relation between vested options and cross-listing.

- 6 Consistent with our findings, prior literature documents similar behaviour for US corporate insiders. For instance, Bardov and Mohanram (2004) find that executive stock option exercises represent private information about disappointing earnings in the post-exercise period. Similarly, Skaife et al. (2013) find that insider trading profitability, driven by insider selling, is significantly greater in firms disclosing material weaknesses in internal control relative to firms with effective control.

- 7 CEO power may also partly arise from their ability to affect the selection of directors (Shivdasani and Yermack, 1999).

- 8 We adjusted compensation data using the inflation rates of the Canadian Consumer Price Index retrieved from the International Financial Statistics (IFS) database.

- 9 We focused on compensation data for CEOs rather than all the executive officers of the firms for the following reasons. First, the CEO is the only executive officer accountable to the board of directors and eventually to the shareholders. Second, considering the compensation of other executives will confound our results because of frequent changes in their positions (Craighead et al., 2004).

- 10 Observing the same CEO around the cross-listing explicitly controls for the effect of managerial talent on CEO compensation.

- 11 With this robustness analysis, we ensure that cross-listings during the period 1999–2000 do not affect long-run performance, suggesting that long-run performance does not reflect bear market and bad news pricing parameters. We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this type of robustness analysis.

- 11 The appendix provides definitions of all variables used in the paper.

- 8 We also use different interaction terms based on alternative definitions of the dummy variable (i.e., cut-off points at the 25 and 75 percentiles for the vested options) and the results were qualitatively similar (untabulated). Note that the basic assumption in these models is that the ln(1 + vested options) has one linear effect within a certain range of its values (e.g., below the cut-off point), and a different linear effect at another range (e.g., above the cut-off point).

- 9 We adjust option compensation variables using logarithms to prevent any change in the distribution of the variables that standardization may introduce. In this vein, Core (2001, p. 445) suggests that ‘… Managers care about their dollar wealth, not their percentage ownership. It is well known that managers of larger firms have fewer options as a fraction of shares outstanding, but the dollar value of these options holdings is much higher than those of small firms (Baker and Hall, 2004) …’.

- 6 We also re-run the analysis using stock return volatility, which controls for the impact of information asymmetry on cross-listing announcement returns. Untabulated results are qualitatively similar to those reported and the coefficient estimate of stock return volatility is statistically insignificant.

- 3 Nevertheless, inferences from analysis using buy-and-hold abnormal returns are qualitatively similar to those reported in Table 5.

- 4 Sadka (2006) provides evidence that firm-level liquidity, decomposed into variable and fixed price effects, is priced, especially in the context of momentum and post-earnings-announcement drift portfolio returns.

- 5 Data for factors were retrieved from the site of K. French and WRDS.

- 3 Among other reasons for stock mispricing are downward corrections of prior over-reactions to news (De Bondt and Thaler, 1985; Wu et al., 2012) and upward corrections due to slow adjustment to firm-specific news (Jegadeesh and Titman, 1993, 2011).

- 4 Note that expiration dates are not publicly available, and thus we cannot directly examine the robustness of the results to this alternative explanation. This explanation, however, is less likely to explain our findings, because Huddart and Lang (1996), using proprietary data, find that most option exercises occur prior to expiration.

- 1 According to the model, the estimate of discretionary accruals is based on the equation −0.229-0.504 + 0.046 x ln(1 + vested options) + 0.074 x P50 x ln(1 + vested options). Evaluating this equation with the median value of vested options, which equals 555.982, the model estimates a lower bound of discretionary accruals equal to 0.625.

- 2 An exception is the relation between discretionary accruals and P50 * ln(1 + vested options) * Non-CL, which is positive and significant (z = 2.29). Further analysis reveals that winsorizing discretionary accruals at the 5% level makes the relation marginal, suggesting that the relation is largely driven by the presence of outliers/influential observations.

- -5 Similar to Cohen et al. (2005) we include cash flow from operations excluding extraordinary items to control for extraordinary firm performance.