The Impact of IFRS 8 Adoption on the Usefulness of Segment Reports

The authors gratefully acknowledge helpful comments from Jacqueline Birt, Florian Eugster, Peter F. Pope, Ian M. Tarrant, and Senyo Tse as well as conference participants at the European Accounting Association 35th Annual Congress 2012 in Ljubljana, 24th Asian-Pacific Conference on International Accounting Issues 2012 in Maui, and the AS-VHB and IAAER Joint Annual Conference 2013 in Eschborn.

Abstract

We analyze the impact of IFRS 8 on the usefulness of segment reports from an investor's perspective. The analysis comprises three steps. First, we compare the value relevance of segment reports before and after the introduction of IFRS 8. Second, we analyze a treatment group of firms that had to change their segmentation upon IFRS 8 adoption and a control group that was unaffected by its introduction. Third, the requirement to report financial information for the current and previous year under current accounting rules allows us to analyze a unique data set of segment reports for the same company and the same year under two different standards. Our results based on German listed firms show superior value relevance of segment reports according to IFRS 8 compared to IAS 14 in all three steps. Additional analyses suggest that the adoption of IFRS 8 is also related to a decline in information asymmetry. Our findings are robust to a number of alternative specifications.

Introduction

Despite the widely acknowledged relevance of segment reporting (e.g., Brown, 1997), there are different views about the approach that is best suited to provide useful segment information. During the 1990s, the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) discussed various concepts for segment reporting (e.g., the risk-and-reward approach versus the management approach) but could not agree on a common standard. In 1997, the IASC issued IAS 14 following the risk-and-reward approach, whereas the FASB published SFAS 131 following the management approach.

In 2006, however, as a result of the short-term convergence project with US-GAAP, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) replaced IAS 14 with IFRS 8 and thereby adopted SFAS 131 with only minor differences. This step has been met with both support and criticism. 1 Two members of the IASB, for instance, expressed dissenting opinions and voted against the new standard. While they supported the management approach for defining reportable segments, they believed that the standard should require the disclosure of segment data in line with IFRS as non-GAAP measures might mislead users. Moreover, the European Parliament expressed concerns about IFRS 8, which delayed the endorsement for almost one year. The European legislator criticized the discretion and potential lack of comparability associated with IFRS 8 and expressed concern about adopting a US accounting standard without assessing the impact for EU law (European Parliament, 2007a). After the European Commission had analyzed the potential consequences of IFRS 8, the European Parliament finally endorsed IFRS 8 (European Parliament, 2007b).

Given the relevance of segment information, the major changes to segment reporting introduced by IFRS 8 and the controversial views about the management approach inherent in the new standard, the IASB initiated a post-implementation review of IFRS 8 in 2012. An IASB staff paper from January 2013 concluded: ‘At this time, there is no academic evidence that application of IFRS 8 has reduced information asymmetry … Studies have generally not considered the impact of IFRS 8 on … the usefulness for investors of segment disclosure based on the management approach’ (IASB, 2013, p. 7).

Therefore, we examine the usefulness of segment reporting under the management approach by analyzing its value relevance in the pre- and post-IFRS 8 periods. Although the value relevance of financial information is not an objective of the IASB's Conceptual Framework, the value relevance approach is used to operationalize the fundamental characteristics of relevance and faithful representation/reliability. 2 An accounting number will turn out to be value relevant if the information is relevant to an investor's equity investment decision and reliable enough to be considered (Barth et al., 2001, p. 80). Hence, we use the value relevance framework to analyze whether the introduction of IFRS 8 improved the usefulness of segment data from investors’ perspectives. To corroborate the value relevance analyses, we provide additional tests of information asymmetry effects measured by bid-ask spreads.

This paper draws on a unique hand-collected sample of segment data reported by German listed firms under IAS 14 (pre-period) and IFRS 8 (post-period) from 2007 to 2010. The German setting is particularly interesting because IFRS 8 requires the management approach for segment reporting, and German firms have traditionally maintained separate records for financial reporting and managerial accounting purposes. Hence, the effect of introducing the management approach to segment reporting should be particularly pronounced for German firms because of the traditional differences between financial and management accounting. Thus, in Germany, there should be more divergence in the segment reports pre- and post-IFRS 8 compared to firms in countries that generally have largely integrated accounting systems.

We address our research question in three ways. First, we simply compare the value relevance of segment reports pre- and post-IFRS 8. While we find a minimal decline in the value relevance of consolidated financial statements from the IAS 14 period (2007–2008) to the IFRS 8 period (2009–2010), we find an increase in the value relevance of segment reporting. Second, we exploit a unique setting whereby a substantial number of our sample firms already reported segmental information in conformity with the management approach under IAS 14 and thus did not have to change the way they presented their segments upon adoption of IFRS 8. This allows for a difference-in-differences design that inherently controls for confounding time effects. While our treatment group of firms that changed their segment reporting upon IFRS 8 adoption shows a substantial increase in value relevance, our control group does not experience a considerable change, which is in line with the general trend in the value relevance of consolidated financial statements from the 2007–2008 to the 2009–2010 period. Third, we take advantage of the fact that firms report the current and previous year in their financial statements based on the current accounting standards. Hence, in the first year of IFRS 8 adoption, firms had to report information for the previous year (lagged-adoption) under IFRS 8 as well. This allows us to use a unique data set of segment reports for the same company and the same year under two different standards. Again, we find that segment information under IFRS 8 yields more value-relevant information. Overall, our three approaches signal that the introduction of IFRS 8 and its use of the management approach improved the value relevance of segment reporting. Finally, we also analyze information asymmetry effects in terms of bid-ask spreads and find that firms experience a decrease in information asymmetry upon adoption of IFRS 8, which is consistent with the findings of the value-relevance analyses. Our results are robust to a number of sensitivity tests and alternative specifications.

This paper contributes to the literature by providing evidence of a superior usefulness of segment reports prepared in accordance with IFRS 8 compared to IAS 14—a result that supports the findings of the IASB's post-implementation review and confirms that the new standard improved the value relevance of financial reporting. This finding may also be of interest for national standard setters contemplating a change in segment reporting rules. Furthermore, we expand the literature by explicitly comparing the suitability of different fundamental approaches to segment reporting (i.e., the management approach versus the risk-and-reward approach) rather than focusing on the usefulness of segment reporting compared to consolidated financial statements as prior work has done (e.g., Boatsman et al., 1993; Bodnar and Weintrop, 1997; Tse, 1998; Givoly et al., 1999). Moreover, some prior studies have analyzed the impact of introducing the management approach to segment reporting (SFAS 131) in a US setting (e.g., Hope et al., 2008; Hossain, 2008). The introduction of SFAS 131, however, meant an increase in segment information compared to the preceding standard (SFAS 14). 3 Thus, it is impossible to disentangle the impact of the change in underlying approaches from a mere increase in the quantity of segment information supplied. In our sample, the level of segment information under IAS 14 and IFRS 8 remained quite similar. IFRS 8 requires a comparable amount of segmental narratives and even fewer line items. Hence, the adoption of IFRS 8 did not mean an increase in segmental disclosures, but rather a change in the underlying rationale so that segments are identified the same way as they are used internally. This allows us to isolate the effect to the change in fundamental principles. Finally, we are the first to find segment information under IFRS value relevant at all.

Institutional Setting

Segment reporting requirements were substantially changed with the adoption of IFRS 8 in November 2006. According to the new standard, companies with publicly traded debt or equity instruments must apply IFRS 8 for fiscal years beginning on or after 1 January 2009. IFRS 8, which replaced IAS 14, is virtually identical to the US-GAAP segment reporting requirements of SFAS 131 issued in 1997. By ostensibly adopting US-GAAP, there was a fundamental change in the principles of segment reporting from the risk-and-reward approach (i.e., IAS 14) to the management approach (i.e., IFRS 8 and SFAS 131). The latter allows users of financial statements to see the entity ‘through the eyes of management’ (Martin, 1997).

Under IFRS 8, segment reporting requirements differ in three main respects: identification of segments, measurement basis used, and reported line items. Regarding the identification of segments, IAS 14 allowed preparers to identify segments according to the risks and returns of either the products or services provided (i.e., business segments) or the regions in which the firm operates (i.e., geographical segments). IFRS 8, by contrast, requires firms to identify segments according to the firm's internal organizational structure and the way in which the firm's chief operating decision maker (CODM) allocates resources and evaluates performance. Moreover, IAS 14 required segment information to be consistent with the general measurement principles of IFRS, whereas IFRS 8 requires segment items to be measured on the same basis that is used internally by the CODM. This implies that segment items may be non-GAAP pro forma measures. Finally, IFRS 8 only mandates the disclosure of those items in the segment report that are provided internally to the CODM, whereas IAS 14 required the firm to disclose specific line items for each reported segment, which increased the comparability of segment reports across firms.

While the IASB was aware of the scope for discretion and decreased comparability across firms associated with the management approach, it felt that the benefits (e.g., more decision-useful information and convergence with US-GAAP) would outweigh the costs. In assessing the possible benefits of IFRS 8 when the new standard was proposed, the IASB had to rely on empirical evidence from the implementation of SFAS 131 in the US. Although prior research indicated improvements in segment reporting under SFAS 131 compared to the previous standard SFAS 14 (e.g., Street et al., 2000; Botosan and Stanford, 2005), these findings cannot be generalized and may not hold in the case of IAS 14. It is rather necessary to analyze the effect of IFRS 8 compared to IAS 14 as the latter differs from SFAS 14 in many ways. In particular, SFAS 14 required far less extensive disclosures than IAS 14. Hence, it is difficult to distinguish whether the findings of US studies are attributable to the introduction of the management approach or merely to increased disclosures (or possibly both).

Moreover, the empirical evidence is limited to US firms, which have a different tradition of organizing their accounting systems and a different structure of capital markets compared to Continental European and in particular German firms. With regard to the accounting system, US firms have one set of financial records for both financial and managerial accounting purposes (i.e., integrated accounting systems), whereas German companies traditionally maintain separate records for financial and managerial purposes (i.e., dual accounting systems) (Kaplan and Atkinson, 1998). The data for managerial accounting often include imputed costs (e.g., imputed depreciation based on replacement cost, imputed interest in terms of the cost of capital, etc.) and exclude neutral expenses (e.g., extraordinary expenses that are not related to a firm's business model) (Schildbach, 1997). The managerial accounting system thereby leads to earnings that differ from those in the financial statements. Although several multinational German firms have integrated their accounting systems in recent years and now use IFRS data for management control (Jones and Luther, 2005), the different tradition may still have an impact on segment reporting under IFRS 8 as non-IFRS profit figures may be reported more often than in other countries. Hence, the specifics of the German accounting tradition, and in addition differences in the capital market structure, make it impossible to generalize findings for US firms to German companies and make the latter an interesting field for research into segment reporting.

Theory and Prior Research

Theoretical Foundation

Segment information in general is an important source of information for financial analysts when valuing a firm (Brown, 1997). Segment reports help to disentangle future cash flow streams that are subject to different economic environments and thus help investors to value the firm (e.g., Tse, 1998; Givoly et al., 1999). However, it is unclear how the change in the underlying principles from the risk-and-reward approach to the management approach will impact the valuations of investors and thus the usefulness of segment data. The IASB noted that the primary benefits of introducing the management approach would be consistency of segment reports with internal management information, segment disclosures that are more in line with other parts of the annual report, an increased number of reported segments, and more segment information in interim financial reports (IFRS 8.BC9). The Board also noted that if IFRS amounts could be prepared reliably and timely under the management approach, this approach would provide the most useful information (IFRS 8.BC13).

Following the IFRS Conceptual Framework, financial information is decision useful if it is relevant and faithfully represents what it purports to represent. Moreover, comparability of financial information is one of the enhancing characteristics of decision usefulness. Since value-relevance tests are used to operationalize these criteria (Barth et al., 2001), we discuss the impact of IFRS 8's adoption in the following.

With regard to relevance, the management approach allows users of financial statements to see the entity ‘through the eyes of management’. Segment reports provide investors with the same information that management uses internally for decision making and performance evaluation. The results of the Jenkins Report suggest that this information is also relevant for external users of financial statements and enhances their ability to monitor management because they receive a more consistent and reliable picture of the company (AICPA, 1994; Martin, 1997). Maines et al. (1997) confirm this finding using experimental evidence. They observe that financial analysts are more confident in their forecasts and consider reports more reliable when segment definitions in the financial statements are identical to those employed internally. Moreover, such segment reports improve the ability of users of financial statements to evaluate future cash flow prospects (Ernst and Young, 1998). Thus, we believe that the possibility of seeing the entity ‘through the eyes of management’ under IFRS 8 will reduce information asymmetry between management and investors and enhance the relevance of segment reports.

However, financial information must also be faithfully represented. One of the main concerns about the introduction of IFRS 8 was that the management approach offers more room for discretion. For instance, a firm could decide to introduce another reporting level at a more aggregated stage and deem this level as the CODM level to avoid the disclosure of information about specific segments. Based on interviews with a broad range of stakeholders, Crawford et al. (2012) highlight how a number of those interviewed feared that some companies might change what is reported to the CODM to avoid disclosure of commercially sensitive segmental information. Hence, there is room for a firm to influence the level and content of segment disclosures. The extent to which firms make use of this discretion will depend on the perceived costs of segment disclosures.

A further concern voiced by the European Parliament was a potential lack of comparability (European Parliament, 2007a). Comparability of financial information, however, is one of the enhancing characteristics of decision usefulness as users’ decisions involve choosing between different investment opportunities. With the introduction of the management approach, comparability across firms will decrease because the financial items disclosed for each segment will depend on the firms’ internal reporting system. It can be assumed that comparability across firms is worse the more differences there are between the managerial and financial accounting system, that is, the less integrated the accounting system is. Moreover, inter-temporal comparability may also be impaired as CEO turnovers or other events often lead to changes of internal reporting systems. The notion of impaired comparability is also supported by Pacter (1994), Herrmann and Thomas (1997), and Emmanuel and Garrod (2002) who recognize that introducing the management approach to segment reporting implies an emphasis of relevance over comparability. 4

Hence, from a theoretical perspective, the relevance of segment reports for users of financial statements should increase. The faithful representation of segment information, however, may be impaired due to the managerial discretion permitted under IFRS 8. Moreover, there will be less cross-company and inter-temporal comparability of segment information. As relevance, faithful representation, and comparability jointly determine the usefulness of financial information and their conceptual analysis is somewhat ambiguous, it is a priori uncertain whether the introduction of IFRS 8 has improved the usefulness of segment information in valuing firms. Therefore, the impact of introducing the management approach to segment reporting on the usefulness of segmental information is ultimately an empirical question.

Prior Research

Several studies have investigated the usefulness of segment reporting (e.g., Kinney, 1971; Kochanek, 1974; Collins, 1976; Simonds and Collins, 1978; Dhaliwal, 1979; Ajinkya, 1980; Aitken et al., 1994; Hu et al., 2010). Most of these studies indicate that segment information is incrementally useful compared to consolidated financial information. Still, the question of which underlying approach of segment reporting is best suited for the provision of useful information is unexplored thus far. In the specific context of IFRS 8's adoption and the introduction of the management approach, there is barely any empirical evidence on its economic consequences. Two concurrent studies by Bugeja et al. (2015) and Leung and Verriest (2015) do not find an impact on analysts’ forecasts or liquidity.

There is some evidence on the impact of IFRS 8 on segment reporting practice. For instance, KPMG (2010), Crawford et al. (2012), Kang and Gray (2013), and Nichols et al. (2012) find an increase in the number of reported segments and a decrease in reported line items upon IFRS 8 adoption for a variety of different countries and firms. However, these studies are solely descriptive. The question whether the introduction of IFRS 8 yields superior usefulness compared to IAS 14 has not been fully answered so far.

Evidence from US studies on SFAS 131 is restricted to geographical segment information using only broad classifications of foreign and domestic geographical segment information (e.g., Hossain and Marks, 2005; Hope et al., 2008; Hossain, 2008). In contrast, we employ very fine segment valuation models which are capable of using line of business as well as geographical segment data and thus do not restrict analysis to geographical numbers. This is particularly important as more than 80% of our sample firms use line of business as the predominant segmentation criterion. Moreover, findings of SFAS 131 studies cannot be generalized to segment reporting under IFRS as the basis for comparison (SFAS 14 vs. IAS 14) is different. Furthermore, most US studies on SFAS 131 only find an impact for firms that previously did not disclose any segment information and started segment reporting under the new standard (e.g., Berger and Hann, 2003; Botosan and Stanford, 2005; Ettredge et al., 2005). Thus, they analyze the economic consequences of a change from no segment information to segment reports under the management approach. We, however, analyze firms that already report segment information and subsequently change the approach under which segment reports are prepared. This allows us to explicitly compare the usefulness of different approaches to segment reporting, namely the management versus the risk-and-reward approach. Moreover, we reduce the research gap on the economic consequences of IFRS 8's adoption.

Research Design and Sample

Empirical Models

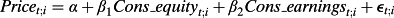

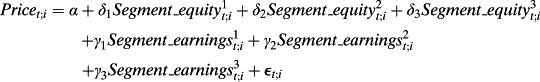

(1)

(1)where:

-

- Pricet;i

-

- = stock price 90 days after the end of financial year t for entity i;

-

- Cons_equityt;i

-

- = book value of equity per share of year t for entity i;

-

- Cons_earningst;i

-

- = income per share of year t for entity i.

Equation 1 shows stock price as a function of the book value of equity and income. The stock price is obtained 90 days after fiscal year-end t. We assume that a lag of three months is sufficient to allow the publication of the annual report and for investors to obtain all the necessary details such that stock prices reflect all publicly available information. 6 Furthermore, we use net income of continued activities as a proxy for income. 7

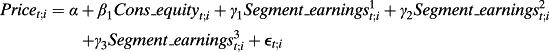

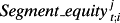

(2)

(2)where:

= income per share of segment j of year t for entity i.

= income per share of segment j of year t for entity i.

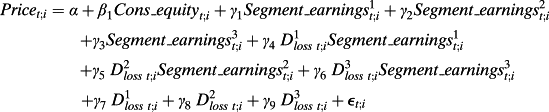

(3)

(3)where:

= book value of equity per share of segment j of year t for entity i.

= book value of equity per share of segment j of year t for entity i.

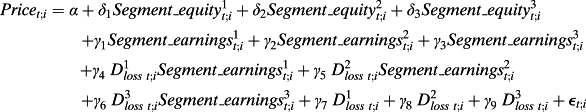

()

() ()

()where:

-

-

- = loss dummy: equals one if segment j of entity i reports a loss for year t, and zero otherwise.

Following prior research, our primary metric for the value relevance of segment reporting is the explanatory power (i.e., the adjusted R2) of these models (e.g., Harris et al., 1994; Collins et al., 1997). We will also present the significance levels of regression coefficients; however, the adjusted R2 reflects the overall ability of accounting data to capture the economic information impounded in stock prices. Moreover, given that many companies operate in related industry sectors even if they show different segments, the significance level of single coefficients may be impaired due to multicollinearity between our segment variables. This multicollinearity, however, does not affect the overall explanatory power of our models and therefore we prefer adjusted R2 as our aggregate metric of value relevance.

Sample

- availability of segment information in the annual financial statements;

- availability of a segment report under IAS 14 and IFRS 8;

- no firms from banking, insurance, or financial services industries; 11

- currency of financial statements is Euro;

- no early adoption of IFRS 8; and

- no coinciding changes such as mergers, divestments, or major structural changes.

The elimination of 19 early adopters is very important because these firms have certain incentives to adopt IFRS 8 early. These incentives may also impact some of the factors that determine the value relevance of segment reports and thus they may unduly influence our results. Moreover, we eliminate three firms that underwent major structural changes that coincided with the adoption of IFRS 8. This allows a cleaner test of the impact of IFRS 8's adoption. Table 1 provides an overview of the sample selection. We require a balanced panel for our analysis. Our final sample consists of 70 firms and 280 firm-year observations.

| Sample size | ||

|---|---|---|

| Firms | Observations | |

| Initial sample of HDAX + SDAX entities 2007–2010 | 160 | 640 |

| Less entities with no segment report | (7) | (28) |

| Less no IAS 14 segment report | (24) | (96) |

| Less bank, insurance, or financial sector entities | (20) | (80) |

| Less entities with different currencies | (3) | (12) |

| Less early adopters | (19) | (76) |

| Less coinciding major structural changes | (3) | (12) |

| Less missing data for the whole period | (6) | (24) |

| Less firms with only two segments | (8) | (32) |

| Final sample for the period 2007–2010 | 70 | 280 |

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics. The mean number of segments is 3.45 under IAS 14 and 3.81 under IFRS 8. This increase in the number of segments upon adoption of IFRS 8 is significant at the 5% level, 12 which is in line with other studies (e.g., Meyer and Weiss, 2010; Nichols et al., 2012). The mean number of reported items per segment decreases from 19.59 to 18.24. This difference, however, is insignificant (p-value = 0.207). In general, the number of segments and segment items are more dispersed under IFRS 8. This could be due to an increased flexibility of reporting based on the management approach. Moreover, in contrast to the German accounting tradition, none of the firms in the final sample disclose non-IFRS line items that are based on imputed costs or differ from IFRS measurements in any other way.

| In million Euros | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Median | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | |||||

| Price | 31.80 | 34.43 | 0.53 | 21.31 | 250 |

| - | - | - | - | - | |

| Cons_equity | 2,553.08 (25.71) | 5,639.81 (43.61) | 31.74 (0.55) | 576.53 (14.96) | 45,978 (335.25) |

| Cons_earnings | 237.87 (2.63) | 789.25 (5.63) | −1,688 (−15.60) | 50.63 (1.50) | 6,835 (45.16) |

| Segment_earnings1 | 283.38 (3.38) | 724.72 (6.51) | −881 (−7.95) | 67.25 (1.68) | 5,909 (56.15) |

| Segment_earnings2 | 56.76 (0.95) | 291.84 (2.12) | −2,144 (−11.50) | 19.60 (0.56) | 1323 (10.93) |

| Segment_earnings3 | 152.44 (0.91) | 634.92 (3.42) | −2,117 (−10.12) | 3.66 (0.12) | 4,628 (22.06) |

| Segment_equity1 | 1,886.55 (21.10) | 6,424.39 (61.50) | −20.99 (−1.77) | 441 (8.44) | 87,786 (834.17) |

| Segment_equity2 | 725.98 (7.66) | 1,588.90 (11.59) | −3,413 (−4.18) | 184.04 (4.15) | 9,512 (90.39) |

| Segment_equity3 | −34.99 (−3.17) | 4,513.40 (40.19) | −62,017 (−589.30) | 11.30 (0.45) | 12,953 (66.78) |

| Number_segments | 3.63 | 1.56 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 9.00 |

| - IFRS 8 | 3.81 | 1.68 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 9.00 |

| - IAS 14 | 3.45 | 1.40 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 8.00 |

| Items_segment | 18.92 | 8.96 | 2.00 | 17.00 | 59.00 |

| - IFRS 8 | 18.24 | 9.01 | 2.00 | 17.00 | 59.00 |

| - IAS 14 | 19.59 | 8.89 | 3.00 | 17.00 | 59.00 |

- Price represents the stock price at day t=90 in Euros. All other variables are presented in million Euros and the deflated variables (by number of shares) are presented in parentheses. The variable Cons_equity represents the consolidated book value of equity. Cons_earnings is the consolidated net income. Segment_earnings1–Segment_earnings3 and Segment_equity1–Segment_equity3 are the respective segment values. Number of segments (Number_segments) and items per segment (Items_segment) are calculated for a sample without application of the three segments criterion to avoid a bias and facilitate comparability with segment disclosure studies.

Under IFRS 8, 80.7% use line of business, 10.7% geographical areas, and 8.6% a mixture of both as the predominant segmentation criterion. Segmentation under IAS 14 is very similar: 82.9% use line of business, 15.7% geographical areas, and one firm even reported a mixed segmentation under IAS 14 although this was not explicitly allowed.

For the difference-in-differences analysis, we divide the sample into two groups: change firms that had to change their segment reporting upon adoption of IFRS 8 and no change firms that already reported segment information in line with the management approach under IAS 14. These are firms that internally structured their segments according to risk and rewards so that there was no need for them to change segment reporting upon adoption of IFRS 8. Descriptive studies of the impact of IFRS 8 on segment disclosures have shown that a substantial number of firms belong to the no change group (e.g., Meyer and Weiss, 2010). This is similar to our sample as only 40% of the German HDAX and SDAX firms changed segmentation upon adoption of the management approach. Fifty-seven percent of these firms increased the number of reported segments by one or two segments and 14% even reported three or four additional segments compared to the previous standard. Eleven percent reported fewer segments and 18% did not change the number of segments but only changed the way of segmentation. 12

Table 3 presents the Spearman correlation coefficients for the variables used in the regression models. 13 The coefficients of the IFRS 8 (IAS 14) period are above (below) the diagonal. Consolidated as well as segment-level earnings and equity variables show a positive and mostly significant association with stock prices. Correlation coefficients between the individual segment variables suggest a certain degree of collinearity between the independent variables of the segment models. As mentioned before, we are not that concerned about multicollinearity in our research design since it does not impact the adjusted R2 of our regressions. However, we address multicollinearity in our robustness tests and find that it is not harmful.

| Price | Cons_earnings | Cons_equity | Segment_earnings1 | Segment_earnings2 | Segment_earnings3 | Segment_equity1 | Segment_equity2 | Segment_equity3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price | 1 | 0.655*** | 0.723*** | 0.494*** | 0.485*** | 0.393*** | 0.386*** | 0.402*** | 0.210 |

| Cons_earnings | 0.623*** | 1 | 0.523*** | 0.684*** | 0.608*** | 0.447*** | 0.245 | 0.202 | 0.213 |

| Cons_equity | 0.592*** | 0.685*** | 1 | 0.415*** | 0.480*** | 0.419*** | 0.614*** | 0.600*** | 0.187 |

| Segment_earnings1 | 0.478*** | 0.746*** | 0.680*** | 1 | 0.335*** | 0.017 | 0.312*** | 0.114 | 0.019 |

| Segment_earnings2 | 0.426*** | 0.551*** | 0.438*** | 0.347*** | 1 | 0.070 | 0.259*** | 0.488*** | 0.041 |

| Segment_earnings3 | 0.290*** | 0.313*** | 0.378*** | −0.033 | 0.024 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.094* | 0.458*** |

| Segment_equity1 | 0.480*** | 0.565*** | 0.761*** | 0.583*** | 0.409*** | 0.248*** | 1 | 0.434*** | −0.426*** |

| Segment_equity2 | 0.340*** | 0.373*** | 0.621*** | 0.455*** | 0.470*** | 0.142* | 0.550*** | 1 | −0.317*** |

| Segment_equity3 | 0.074 | 0.089 | 0.029 | −0.009 | −0.075 | 0.192** | −0.392*** | −0.443*** | 1 |

- Table 3 presents the Spearman correlation coefficients. IFRS 8 variables are above the diagonal and IAS 14 variables are below the diagonal. The variable Price is stock price 90 days after fiscal year-end. The variable Cons_equity represents the consolidated book value of equity. Cons_earnings is the consolidated net income. Segment_earnings1–Segment_earnings3 and Segment_equity1–Segment_equity3 are the respective segment values. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Comparison of the Value Relevance of Segment Reporting Under IFRS 8 and IAS 14

Pre-/Post-adoption Analysis

First, we compare the value relevance of segment reporting under the IFRS 8 period (2009–2010) to that during the IAS 14 period (2007–2008). Table 4 presents the empirical findings. Results are based on a pooled OLS regression. We use heteroscedasticity- and autocorrelation-consistent variance estimators. Alternatively, we cluster standard errors at the firm-level, which does not change results or inferences. Moreover, we winsorize all variables at their 1 and 99 percentile level to mitigate the effect of outliers. 13

| Panel A | Panel B | Panel C | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Model 1 IAS 14 | Model 1 IFRS 8 | Model 2 IAS 14 | Model 2 IFRS 8 | Model 2a IAS 14 | Model 2a IFRS 8 | Model 3 IAS 14 | Model 3 IFRS 8 | Model 3a IAS 14 | Model 3a IFRS 8 |

| Segment_earnings1 (+) | 1.175 (1.247) | −0.181 (−0.181) | 0.990 (0.928) | 0.131 (0.121) | 0.480 (0.443) | 0.552 (0.628) | 0.457 (0.379) | 0.820 (0.901) | ||

| Segment_earnings2 (+) | 5.175*** (2.918) | 5.533*** (4.228) | 5.206** (2.301) | 5.980*** (3.508) | 5.458*** (2.641) | 2.287* (1.406) | 6.391** (1.924) | 2.623 (1.036) | ||

| Segment_earnings3 (+) | 3.501*** (2.500) | 4.276*** (3.659) | 3.485** (2.293) | 4.955*** (3.998) | 4.933*** (3.326) | 4.038*** (2.973) | 4.742*** (2.747) | 3.981*** (2.798) | ||

| Loss1* Segment_earnings1 (−) | 4.709 (0.404) | −12.448* (−1.310) | −5.891 (−0.590) | −27.156** (−2.012) | ||||||

| Loss2* Segment_earnings2 (−) | 1.241 (0.409) | −8.622*** (−2.547) | −1.126 (−0.213) | −4.490 (−0.622) | ||||||

| Loss3* Segment_earnings3 (−) | −4.108* (−1.434) | −5.514** (−2.083) | 0.810 (0.243) | 0.835 (0.208) | ||||||

| Loss1 (−) | 2.430 (0.277) | −11.842* (−1.536) | −5.037 (−0.614) | −14.502 (−0.978) | ||||||

| Loss2 (−) | 1.719 (0.395) | −7.088** (−1.962) | 6.488 (1.117) | −8.630* (−1.598) | ||||||

| Loss3 (−) | −7.090** (−2.002) | −3.016 (−0.784) | −11.205** (−2.216) | −4.898 (−0.763) | ||||||

| Segment_equity1 (+) | −0.017 (−0.133) | 0.043 (0.423) | −0.042 (−0.282) | −0.008 (−0.075) | ||||||

| Segment_equity2 (+) | −0.368 (−0.582) | 1.095*** (2.911) | −0.594 (−0.718) | 0.743* (1.482) | ||||||

| Segment_equity3 (+) | −0.151 (−0.365) | 0.768*** (2.837) | ||||||||

| −0.195 (−0.418) | 0.678*** (2.544) | |||||||||

| Cons_earnings (+) | 3.899*** (3.518) | 3.334*** (2.625) | ||||||||

| Cons_equity (+) | 0.080 (0.494) | 0.191* (1.434) | −0.011 (−0.066) | 0.201** (1.686) | −0.003 (−0.020) | 0.115 (0.866) | ||||

| Constant | 14.589*** (6.653) | 22.035*** (9.539) | 14.970*** (6.109) | 20.730*** (10.642) | 16.418*** (5.393) | 21.488*** (8.657) | 19.192*** (5.812) | 20.402*** (6.827) | 21.965*** (5.557) | 24.642*** (6.069) |

| Observations | 140 | 140 | 140 | 140 | 140 | 140 | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.388 | 0.373 | 0.376 | 0.512 | 0.388 | 0.558 | 0.324 | 0.501 | 0.359 | 0.548 |

- Table 4 presents the OLS regression results of the consolidated (1) and segment models (2, 2a, 3, 3a) separately under IAS 14 and IFRS 8. The dependent variable P is stock price 90 days after fiscal year-end. The variable Cons_equity represents the consolidated book value of equity. Cons_earnings is the consolidated net income. Segment_earnings1–Segment_earnings3 and Segment_equity1–Segment_equity3 are the respective segment values. Loss1*Segment_earnings1–Loss3*Segment_earnings3 are segment earnings interacted with loss dummy variables for the respective segments. The predicted signs are presented below the variables in parentheses. The table reports OLS coefficient estimates and t-statistics in parentheses based on heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation consistent standard errors. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (one-tailed), respectively.

Earnings and equity coefficients are expected to be positive, whereas loss response coefficients should be negative. 13 Results are subdivided into three panels. Panel A shows the simplified Ohlson model on the consolidated firm-level. Panel B reports the segment models with segment-level earnings and consolidated equity while Panel C also breaks down equity to segment level.

Model (1) shows the basic consolidated Ohlson model. Earnings are highly significant in both periods with p-values of <0.01 while equity is only significant at the 0.10 level for the IFRS 8 period. On average, there is a slight decrease in the adjusted R2 from the IAS 14 period (38.8%) to the IFRS 8 period (37.3%). Running yearly regressions shows that the consolidated model (1) yields an explanatory power of 39.4% in 2007, 45.4% in 2008, and just 26% in 2009. This trend is possibly due to the aftermath of the global financial crisis which caused substantial uncertainties at the capital markets. By 2010, however, there is a recovery of the value relevance of consolidated financial statements (adjusted R2 = 47.6%). This general trend in the value relevance of aggregated financial information should be kept in mind when analyzing the value relevance of segment reports in the IAS 14 and IFRS 8 periods.

Panel B reports the results of models (2) and (2a) each under both standards. Model (2) incorporates consolidated equity- and segment-level earnings. The segment-level earnings of segments two and three are highly significant at the 0.01 level under both standards. The equity response coefficient is insignificant under IAS 14 and significant at the 0.05 level under IFRS 8. Contrary to the consolidated models, the adjusted R2 is substantially higher in the IFRS 8 period (51.2%) compared to the IAS 14 period (37.6%), indicating an increase in the value relevance of segment earnings under IFRS 8. Model (2a) employs segment loss dummies to control for any potential non-linearity in the response coefficients for loss-making segments (Hayn, 1995). The results, however, are very similar to model (2). Segment earnings are significant for segment two and three at the 0.01 level under IFRS 8 and at the 0.05 level under IAS 14. The loss-interaction terms are only significant under IFRS 8. The discrepancy in explanatory power even increases with an adjusted R2 of 55.8% for the IFRS 8 period and 38.8% for IAS 14. Also note that segment information under IAS 14 is not incrementally useful to consolidated financial statements information. This, however, changes upon adoption of IFRS 8 when the explanatory power of segment models exceeds that of the consolidated model.

Panel C presents the results for models (3) and (3a), which employ equity and earnings on a segment basis. The number of observations decreases to 94 firms under either standard as some firms do not report assets and liabilities to proxy for equity at the segment level. 14 These observations are removed from the sample. Segment equity is insignificant under IAS 14. However, it is highly significant at the 0.01 level for segment two and three under IFRS 8. This may be due to the fact that in case an entity reports segment equity in its IFRS 8 segment report, it is actually an item reported to and used by management. Again, there is a substantial increase in the explanatory power of the segment models (3) (32.4% to 50.1%) and (3a) (35.9% to 54.8%) from the IAS 14 to the IFRS 8 period signalling higher value relevance of segment reports under the new standard.

We also re-run all regressions based on just one year before (2008) and one year after (2009) IFRS 8's adoption. Although this cuts our sample sizes in half, we find similar results and inferences supporting an increase in the value relevance of segment reports under IFRS 8.

The increase in value relevance after the adoption of IFRS 8 has to be interpreted carefully. It could be driven by any confounding time effects such as the introduction of other regulations or general economic trends that might impact value relevance. The fact that there was no change in the general value relevance of consolidated financial statements, however, contradicts the notion of general economic trends causing the increase in the value relevance of segment reporting. Moreover, there were no other segment reporting-related regulations enacted in the period of our analysis. Finally, note that the overall explanatory power of the valuation models of segment information under IAS 14 is very similar to those of the consolidated financial statements information. Hence, there is no superior value relevance of IAS 14 segment reports compared to consolidated numbers. This is different under IFRS 8: segment information under the management approach shows superior value relevance compared to aggregated financial statements information.

Difference-in-differences Analysis

Nonetheless, to rule out alternative explanations that could be driving our results, we exploit the unique setting of the introduction of IFRS 8. There is a substantial number of firms that already reported in compliance with the management approach under IAS 14 and thus were unaffected by the introduction of IFRS 8 (no change firms). This allows for a difference-in-differences design that controls for confounding time effects. Firms that had to change their segmentation upon IFRS 8 adoption (change firms) are exposed to the same economic environment as no change firms. When assuming that the adoption of the new standard is exogenous, we have a quasi-natural experiment with the change firms being the treatment group and the no change firms the control group. 15

Table 5 reports the results for the difference-in-differences analysis. For each of the segment models (2), (2a), (3), and (3a), we run four regressions. First, we split the sample according to the treatment (change) and the control group (no change). Then we compare the value relevance of segment reporting pre and post the adoption of the new standard for each group. In theory, there should not be a difference for the no change group from the IFRS 8 to the IAS 14 period apart from general time effects. However, if there is an improvement in the decision usefulness of segment reporting due to the introduction of IFRS 8 and the management approach, the change group should be affected. Again, we focus on the adjusted R2 as an aggregated measure of value relevance. The significance levels of segment earnings and equity, however, provide corresponding findings.

| (2) | (2) | (2) | (2) | (2a) | (2a) | (2a) | (2a) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | No change IAS 14 | No change IFRS 8 | Change IAS 14 | Change IFRS 8 | No change IAS 14 | No change IFRS 8 | Change IAS 14 | Change IFRS 8 |

| Segment_earnings1 | 2.480** | 1.085 | −0.268 | −2.159 | 2.138 | 1.417 | −0.305 | −1.609 |

| Segment_earnings2 | 3.111* | 2.145** | 6.448** | 5.746*** | 1.604 | 0.981 | 7.692** | 7.699*** |

| Segment_earnings3 | 3.966** | 4.228** | 3.761* | 6.398*** | 3.774** | 5.244** | 3.042 | 6.053*** |

| Loss1* Segment_earnings1 | 22.498** | −4.870 | −8.241 | −35.516*** | ||||

| Loss2* Segment_earnings2 | 4.863 | 0.839 | 1.638 | −12.209*** | ||||

| Loss3* Segment_earnings3 | −4.572 | −6.787*** | −0.248 | 1.825 | ||||

| Loss1 | 14.129 | −5.441 | −3.859 | −26.354*** | ||||

| Loss2 | −2.424 | −4.681 | 11.036 | −4.651 | ||||

| Loss3 | −6.663 | −2.117 | −13.365** | −9.449** | ||||

| Cons_equity | 0.093 | 0.578** | 0.033 | 0.222*** | 0.273 | 0.573** | 0.026 | 0.143** |

| Constant | 9.904*** | 15.473*** | 17.720*** | 19.816*** | 11.018** | 16.868*** | 18.233*** | 20.291*** |

| Observations | 84 | 84 | 56 | 56 | 84 | 84 | 56 | 56 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.410 | 0.513 | 0.396 | 0.697 | 0.436 | 0.559 | 0.441 | 0.771 |

| Δ in Adj. R-squared | +0.103 | +0.301 | +0.123 | +0.330 | ||||

| Diff-in-diff. Adj. R-squared | +0.198 | +0.207 | ||||||

| (3) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (3a) | (3a) | (3a) | (3a) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | No change IAS 14 | No change IFRS 8 | Change IAS 14 | Change IFRS 8 | No change IAS 14 | No change IFRS 8 | Change IAS 14 | Change IFRS 8 |

| Segment_earnings1 | 0.665 | 0.608 | 0.654 | −1.434 | 0.654 | 0.100 | 1.270 | −0.168 |

| Segment_earnings2 | 1.606 | 2.542* | 13.477*** | 3.096* | 1.522 | 3.496 | 21.763*** | 6.952* |

| Segment_earnings3 | 5.051*** | 5.474** | 3.443** | 5.133*** | 4.539** | 5.012* | 3.069* | 4.230** |

| Loss1* Segment_earnings1 | 184.328** | −18.063 | −2.737 | −49.980*** | ||||

| Loss2* Segment_earnings2 | −0.990 | −7.516 | −9.076 | −9.270 | ||||

| Loss3* Segment_earnings3 | 8.695 | −3.171 | 8.399** | 0.981 | ||||

| Loss1 | 10.900 | −11.508 | 17.626* | −43.380*** | ||||

| Loss2 | −1.738 | −7.759 | 30.120 | 1.940 | ||||

| Loss3 | −3.237 | −12.342 | −20.228*** | −10.960*** | ||||

| Segment_equity1 | 0.347 | 0.546** | 0.055 | 0.132** | 0.279 | 0.583* | 0.013 | 0.059 |

| Segment_equity2 | −0.705 | −0.330 | 0.820* | 2.139*** | −0.659 | −0.876 | −0.063 | 1.987*** |

| Segment_equity3 | −0.031 | 0.288 | −0.153 | 0.871*** | −0.039 | 0.183 | −0.386 | 1.082*** |

| Constant | 21.201*** | 27.460*** | 8.040** | 13.535*** | 24.223*** | 35.583*** | 1.051 | 11.320** |

| Observations | 52 | 52 | 42 | 42 | 52 | 52 | 42 | 42 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.350 | 0.398 | 0.510 | 0.826 | 0.387 | 0.456 | 0.633 | 0.891 |

| Δ in Adj. R-squared | +0.048 | +0.316 | +0.069 | +0.258 | ||||

| Diff-in-diff Adj. R-squared | +0.268 | +0.189 | ||||||

- Table 5 presents the OLS regression results for the difference-in-differences analysis. For each segment model (2, 2a, 3, 3a), we report four regression models: pre- and post-IFRS 8 for both the control group (no change) and the treatment group (change). For brevity, we do not report the t-values under the coefficient estimates. The dependent variable Price is stock price 90 days after fiscal year-end. The variable Cons-equity represents the consolidated book value of equity. Cons_earnings is the consolidated net income. Earnings1–Earnings3 and Equity1–Equity3 are the respective segment values. Loss1*Segment_earnings1–Loss3*Segment_earnings3 are segment earnings interacted with loss dummy variables for the respective segments. The predicted signs are presented below the variables in parentheses. The table reports OLS coefficient estimates based on heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation consistent standard errors. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (one-tailed), respectively.

Models (2) and (2a) show that the no change firms experienced a relatively modest increase in the value relevance from IAS 14 to IFRS 8 (+10.3 percentage points in adjusted R2 for model (2); +12.3 percentage points for model (2a)). In contrast, the treatment group of change firms shows a substantial increase in explanatory power of +30.1 percentage points for model (2) and +33.0 percentage points for model (2a). The difference-in-differences in adjusted R2 of +19.8 percentage points for model (2) and +20.7 percentage points for model (2a) show a large incremental improvement in the value relevance of segment reports for those firms that had to change their segmentation upon the adoption of IFRS 8 and as they moved from the risk-and-reward to the management approach. The results are even stronger for model (3) and model (3a): while the control group does not experience much of a change in adjusted R2 (+4.8 percentage points for model (3) and +6.9 percentage points for model (3a)), the treatment group shows an increase of more than +31.6 percentage points for model (3) and +25.8 percentage points for model (3a) upon adoption of IFRS 8. This supports the notion that the improvement in the value relevance of segment reporting is driven by the adoption of the new rule and not by other concurrent developments. Otherwise there should not have been such a substantial difference between the treatment and the control groups as companies switched from IAS 14 to IFRS 8. 15

Lag-adoption Year Analysis

We also exploit the fact that firms must provide information for the current and previous year in their financial statements based on the current accounting standards. This means that in the first year of IFRS 8's adoption, the segment report for the previous year had to be presented according to the new requirements (lag-adoption year). In addition to the previous analysis in the simple pre/post setting and the difference-in-differences design, we can use a unique data set of segment information according to IFRS 8 and IAS 14, each for the same year. The same sample selection criteria apply as for the basic panel. For the analysis, we compare the value relevance of segment earnings and equity for two sub-samples of IFRS 8 and IAS 14 segment reports of the same year. Consequently, if differences are identified based on this data set, it is highly likely that these are due to the dissimilarity of the standards.

Model (2) incorporates consolidated equity and segment earnings. The results in Table 6 show a higher explanatory power for the model incorporating data based on the new standard. The adjusted R2 for IFRS 8 data is 53.3% compared to 36.7% of IAS 14 and the IFRS 8 subsample shows two highly significant segment earnings coefficients compared to just one under IAS 14. Loss dummies (model (2a)) enhance the explanatory power for both sub-samples. Adjusted R2 statistics also supply evidence in favour of IFRS 8 (61.9%) compared to IAS 14 (44.4%) in terms of explanatory power. We employ a Vuong test (Vuong, 1989), which is a likelihood ratio-based test and is applicable for comparing non-nested or overlapping models, to check whether the difference in the explanatory power of the IFRS 8 and IAS 14 models is significant. We find that both models ((2) and (2a)) perform significantly better under IFRS 8 at the 0.05 level. Moreover, comparing the segment models (3) and (3a) shows similar results in favour of IFRS 8. The adjusted R2 based on model (3) is significantly higher under IFRS 8 with 65.1% compared to 38.8% under IAS 14. Using model (3a), there is a difference of +23.3 percentage points in adjusted R2 for IFRS 8 segment data. Both of these differences in adjusted R2 are significant at the 0.01% level. These results once more provide evidence for a superior association of market value and segment data based on IFRS 8 as compared to IAS 14 and thus for the higher value relevance of the former. This test indicates that some of the information under IFRS 8 was already known through other channels before its disclosure in the segment report.

| VARIABLES | Model 2 IAS 14 | Model 2 IFRS 8 | Model 2a IAS 14 | Model 2a IFRS 8 | Model 3 IAS 14 | Model 3 IFRS 8 | Model 3a IAS 14 | Model 3a IFRS 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segment_earnings1 (+) | 0.462 (0.463) | 0.960 (1.104) | 0.907 (0.790) | 1.893** (2.062) | 0.175 (0.134) | 1.496* (1.504) | 0.097 (0.069) | 1.285 (1.148) |

| Segment_earnings2 (+) | 2.511*** (2.486) | 1.561*** (3.823) | 3.870** (2.062) | 0.602 (0.585) | 3.390** (2.272) | 1.694** (2.346) | 6.445** (2.117) | 1.345 (0.531) |

| Segment_earnings3 (+) | 1.566 (1.098) | 3.643*** (3.458) | 2.749** (2.360) | 4.982*** (4.762) | 4.016*** (2.630) | 5.189*** (3.349) | 4.390** (2.358) | 4.628** (2.361) |

| Loss1* Segment_earnings1 (−) | 42.195 (2.231) | 55.301 (4.318) | 14.298 (0.764) | 106.572 (1.528) | ||||

| Loss2* Segment_earnings2 (−) | −2.525 (−1.250) | 1.134 (0.982) | −5.388* (−1.368) | −0.554 (−0.159) | ||||

| Loss3* Segment_earnings3 (−) | −5.356 (−1.290) | −7.299*** (−2.559) | 2.956 (0.484) | 8.070 (0.762) | ||||

| Loss1 (−) | 14.722 (1.237) | 7.215 (0.873) | 3.174 (0.243) | 8.799 (0.733) | ||||

| Loss2 (−) | 0.854 (0.226) | −3.433 (−1.243) | 8.945* (1.447) | −3.706 (−0.989) | ||||

| Loss3 (−) | −4.480 (−1.075) | −6.628** (−1.936) | −8.989 (−1.229) | 8.675 (0.759) | ||||

| Segment_equity1 (+) | 0.092 (0.679) | 0.124 (1.233) | 0.070 (0.415) | 0.144 (1.179) | ||||

| Segment_equity2 (+) | −0.538 (−1.114) | −0.238 (−0.512) | −1.101* (−1.445) | −0.100 (−0.121) | ||||

| Segment_equity3 (+) | −0.254 (−0.641) | 0.131 (0.328) | −0.466 (−0.836) | 0.255 (0.435) | ||||

| Cons_equity (+) | 0.128 (0.702) | 0.090 (0.746) | −0.047 (−0.348) | −0.069 (−0.631) | ||||

| Constant | 10.662*** | 9.463*** | 10.393*** | 10.825*** | 14.681*** | 9.974*** | 14.806*** | 10.513*** |

| (4.970) | (4.768) | (3.766) | (4.615) | (5.155) | (5.006) | (4.683) | (4.227) | |

| Vuong test | 1.794* | 2.161** | 2.569*** | 2.172** | ||||

| p-value | 0.073 | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.015 | ||||

| Observations | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.367 | 0.533 | 0.423 | 0.616 | 0.388 | 0.651 | 0.478 | 0.670 |

- Table 6 presents the OLS regression results for the segment models (2, 2a, 3, 3a) based on segment reports for the last year of IAS 14 and for segment reports of the same year and the same firms under IFRS 8 (lag-adoption year). The dependent variable Price is stock price 90 days after fiscal year-end. The variable Cons_equity represents the consolidated book value of equity. Cons_earnings is the consolidated net income. Segment_earnings1–Segment_earnings3 and Segment_equity1–Segment_equity3 are the respective segment values. Loss1*Segment_earnings1–Loss3*Segment_earnings3 are segment earnings interacted with loss dummy variables for the respective segments. The predicted signs are presented below the variables in parentheses. The table reports OLS coefficient estimates and t-statistics in parentheses based on heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation consistent standard errors. We report the z-values in the first column of the Vuong test and the p-values below. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (one-tailed), respectively.

Supplementary Information Asymmetry Analysis

Given the critique of the value relevance approach (e.g., Holthausen and Watts, 2001), we also use a supplementary analysis of information asymmetries to gauge the usefulness of segment reports under the management approach for investors. Following Blanco et al. (2015), we believe that segment reports under the management approach impact information asymmetry through two channels. First, an improvement in a firm's information environment permits a more precise estimation of future cash flows and thereby leads to a reduction in estimation risk. Second, more useful segment information allows better and cheaper monitoring of management, in particular, when investors receive information ‘through the eyes of management’. However, information asymmetry will only be affected if the adoption of the management approach led to more useful information.

Owing to its strong theoretical foundation, we use bid-ask spreads to capture information asymmetries. Similar to prior literature (e.g., Daske et al., 2008), we measure bid-ask spreads as the median of the difference between the daily closing bid and ask prices divided by the midpoint for the nine-month period starting 90 days after fiscal year-end. In a difference-in-differences setting, we compare bid-ask spreads of our change and no change firms before and after the adoption of IFRS 8. In Panel A of Table 7, we compare the mean bid-ask spreads of our control group and our treatment group the year before and the year after IFRS 8's adoption. Spreads are very similar in the pre-adoption period with an average of 0.665% for the treatment group and 0.696% for the control group. In 2009, the treatment group experiences a decline in spreads of −0.030 percentage points while the spreads of the control group increase by 0.077 percentage points. The difference-in-differences of −0.107% is marginally insignificant which may be due to the small sample sizes in each bin. 15 Extending the pre- and post-adoption period to two years each and thereby increasing the power of our estimation, we find a significant difference-in-differences of −0.044%. The results of the spread analysis support the initial findings that firms adopting the management approach experience an improvement in the usefulness of segment reports.

| Bid-ask spread Panel A 2008/2009 | IAS 14 (Pre adoption) | IFRS 8 (Post adoption) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (b)–(a) | ||

| Change firms (n=24 firm-years) | (i) | 0.665% | 0.635% | −0.030% |

| No change firms (n=41 firm-years) | (ii) | 0.696% | 0.773% | +0.077% |

| (i)–(ii) | −0.031% | −0.138% | −0.107% | |

| Bid-ask spread Panel B 2007–2010 | IAS 14 (Pre adoption) | IFRS 8 (Post adoption) | ||

| (a) | (b) | (b) – (a) | ||

| Change firms (n=48 firm-years) | (i) | 0.584% | 0.606% | +0.022% |

| No change firms (n=82 firm-years) | (ii) | 0.627% | 0.693% | +0.066% |

| (i)–(ii) | −0.043% | −0.087% | −0.044%* |

- Table 7 presents the information asymmetry analysis based on the difference-in-differences design. Panel A reports mean values of bid-ask spreads for the change firms (treatment group) and no change firms (control group) before (2008) and after (2009) the adoption of IFRS 8. Panel B uses two-year windows for the IAS 14 period (2007–2008) and the IFRS 8 period (2009–2010). Bid-ask spread is measured as the median of the difference between the daily closing bid and ask prices divided by the midpoint for the nine-month period starting 90 days after fiscal year-end. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance of differences in means at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively, based on non-parametric ranksum tests. We assess the statistical significance of the difference-in-differences value (i.e., the lower right-hand side number) by comparing the means of firm-level changes from the IAS 14 to the IFRS 8 period using non-parametric ranksum tests.

Additional Analyses and Robustness Tests

To check the sensitivity of the results, we perform several additional analyses and robustness tests. The results of alternative specifications will not be discussed in depth if they are similar to the primary findings. However, significant differences are highlighted.

Two Segment Models

Initial results are based on valuation models that employ variables for three segments. To check whether the results are sensitive to the number of segments employed in the valuation models, we also estimate models based on two and four segments. Results are similar for all three different steps and conclusions remain unchanged. Four segment models, however, substantially decrease the sample size and should thus be interpreted carefully.

Variation of the Dependent Variable

Veith and Werner (2014) show that the choice of the return window can substantially impact the findings of value-relevance studies. We use stock price 90 days after fiscal year-end as the dependent variable in the original model. To ensure that the results are not driven by a specific event on that day, we also employ the mean stock price of a 20-day window (80–100 days after fiscal year-end) as a robustness check. Additionally, following other value-relevance studies (e.g., Giner and Reverte, 1999; Cazavan-Jeny and Jeanjean, 2006; Al Jifri and Citron, 2009), we use stock price at fiscal year-end (t=0). Neither of the alternative dependent variables leads to different results compared to the original models. Moreover, the results of Veith and Werner (2014) also indicate that the return window that maximizes the adjusted R2 of value relevance regressions differs between countries. In Germany, capital markets seem to take longer to fully impound financial information into prices. Hence, we also re-run all regressions with stock prices 120 and 150 days after fiscal year-end. Yet, our results and inferences remain unchanged.

Additional Controls

Prior research has found several factors that moderate value relevance on the consolidated level. For instance, Collins and Kothari (1989) find a significant association of the earnings response coefficient with the growth opportunities and risk of a firm. They suggest to proxy for growth opportunities by the market-to-book value of equity and for the riskiness of earnings by common stock betas. They provide evidence that the statistical association is significantly understated if one fails to control for growth opportunities. Hence, we incorporate these variables in our regression models. Once again, the general explanatory power of all specifications increases, but results and inferences are very similar.

Geographical Segmentation and Outlier Treatment

About 15% of our sample firms use geographical segments as their primary segmentation. To ensure that results are insensitive to the type of segmentation employed, we also estimate all regressions only based on line-of-business firms. Again, this does not change our results.

Beyond these alternative specifications, we carry out some outlier detection tests as prior research indicates that extreme observations potentially cause a non-linear relationship between security prices and earnings (Wysocki, 1998). Following, for instance, Ali and Zarowin (1992), extreme observations might include value-irrelevant or transitory elements, which could have an undue impact on the findings. However, removing observations from our sample flagged as outliers based on Cook's Distance (Cook, 1977) does not change the general tenor of our results.

Multicollinearity

The correlation matrix in Table 3 indicates a certain degree of pairwise collinearity between the independent variables. Because pairwise correlation coefficients are not sufficient to check for the presence of multicollinearity, we analyze the variance inflation factors (VIFs) of all our models. In most specifications, the VIFs are below five suggesting no harmful multicollinearity. Yet, in a few models the VIFs exceed 10. The standard errors of those coefficients could be inflated and thus make it more difficult to find statistically significant coefficients. However, this is not a major issue in this study because we are primarily interested in the overall explanatory power of the valuation models rather than the significance level of single coefficients. In addition, we employ a procedure which suggests that weak (strong) multicollinearity is associated with condition indices around 5–10 (30–100) and the variance decomposition proportion is beyond 50% for more than two coefficient variances of the respective eigenvalue. In this case, condition indices and eigenvalues indicate that strong multicollinearity is not a problem in any of our specifications.

Conclusions

Our findings show that segment information according to IFRS 8 is more value relevant and reduces information asymmetry compared to segment data reported under IAS 14. The benefits of the new segment reporting requirements for investors seem to outweigh their potential drawbacks (e.g., less comparability between firms), a finding which is of interest to the IASB and other standard setters considering changes in segment reporting rules. All in all, financial accounting information ‘through the eyes of management’ appears to increase the value of information from an investor's perspective. Moreover, it might also be of interest to standard setters that the value relevance of segment reports under IAS 14 is largely driven by segment earnings rather than equity. Under IFRS 8, in contrast, segment equity yields explanatory power in our valuation models. This is in line with the fact that only firms that report segment assets and segment liabilities internally need to disclose them under IFRS 8. This also supports the decision of the IASB to remove the mandatory disclosure of segment assets in the amendments of IFRS 8 through the annual improvements to IFRS in 2009.

However, some limitations remain. Inherent assumptions of the value relevance framework limit our inferences to the relevance and reliability of segment reporting from an investor's perspective. Additionally, we focus on German firms. We intentionally chose the German setting as we expected a particularly pronounced impact of introducing IFRS 8 due to Germany's tradition of maintaining separate records for financial reporting and managerial accounting purposes. We acknowledge that IFRS-applying countries such as Australia, Canada, or Hong Kong, which are very different in terms of culture, may be affected differently. In particular, the introduction of the management approach may be evaluated in a different way due to differences in the perceived reliability of segment information based on internally used figures. However, we leave this aspect for future research.

Finally, the comparison of the two segment reporting standards is based on data from the first two years of IFRS 8 adoption. Although this provided a unique setting for the analysis, firms as well as their respective auditors may not have been fully accustomed to the new requirements. Hence, differences found between IFRS 8 and IAS 14 can be due to unique effects which abate once companies and auditors gain more experience. On the other hand, these differences may well increase.

The convergence of IFRS and US-GAAP segment standards led to identical segment reporting requirements for numerous countries and firms worldwide. We provide empirical evidence on the superior usefulness of segment disclosures under IFRS 8 compared to IAS 14 for investors. While this study sheds light on the potential benefits of IFRS 8, future studies could analyze the costs of adopting IFRS 8. This is particularly interesting given the proprietary nature of information ‘through the eyes of management’ (Martin, 1997).

References

- 1 See Crawford et al. (2014) for a detailed discussion of the political controversy surrounding the introduction of IFRS 8.

- 2 Note that the IASB issued changes to the Conceptual Framework as part of the IASB Agenda Project in September 2010. The fundamental qualitative characteristic reliability was replaced by the term ‘faithful representation’ due to the vagueness of the meaning of the former. We will use both terms interchangeably.

- 3 SFAS 14 was heavily criticized due to its loose requirements. In 1993, the Association for Investment Management and Research (AIMR) requested segment information to be more disaggregated and asked for more information for each segment than was reported under SFAS 14 (Herrmann and Thomas, 2000). This was addressed with the introduction of SFAS 131 (FASB, 1997, paras 41–45).

- 4 Emmanuel and Garrod (2002) imply that the introduction of the management approach may reduce comparability and relevance in some cases.

- 5 This model has been used in numerous value-relevance studies, for instance, Joos and Lang (1994), Giner and Rees (1999), and Francis and Schipper (1999). Furthermore, Barth and Clinch (2009) show that using number of shares as a deflation factor in the modified Ohlson (1995) model is better to reduce scale effects than using equity book value, price, or lagged-price as alternative deflation factors.

- 6 We also use different lag windows in our robustness tests section and find that our results do not depend on the length of the estimation window.

- 7 Excluding profit from discontinued operations theoretically leads to a violation of the clean surplus identity. However, Dechow et al. (1999) argue that these items are nonrecurring, and speaking from a practical point of view, they maintain that the inclusion would probably not enhance the model.

- 8 All firms in our sample quantify income on segment level by EBIT-related profit measures. Therefore, we use EBIT as the consolidated amount when determining the earnings of segment three:

equals Cons_EBITt;i – (

equals Cons_EBITt;i – (

+

+

).

). - 9

equals

equals

where K is the total number of reported segments.

where K is the total number of reported segments. - 10 The HDAX index is calculated by Deutsche Börse Group and comprises the main indices DAX (30), MDAX (50), and TecDAX (30). The SDAX consists of 50 firms. All indices belong to the Prime Standard market segment.

- 11 This is consistent with a vast number of empirical accounting studies as these sectors differ significantly from other industries in terms of business model and regulation.

- 12 We use normal t-tests as well as non-parametric ranksum tests. The results, however, are similar.

- 12 The latter are firms that use an entirely different way of segmentation, but they happen to have the same number of segments.

- 13 We also use (but do not tabulate) Pearson instead of Spearman rank correlation coefficients, which point to evidence in the same direction.

- 13 However, inferences without winsorizing are virtually the same except for the slightly lower explanatory power of the models.

- 13 One-tailed t-tests of coefficients are used if the respective variable has a predicted sign and two-tailed tests otherwise.

- 14 Because the disclosure of segment assets and liabilities was mandatory under IAS 14, the decline in sample size is largely driven by firms that stop to report either segment assets or liabilities under IFRS 8. We retain a balanced sample and only use firms that provide sufficient data to proxy for segment equity under both standards. We acknowledge that this is likely a biased sub-sample of the firms in the earnings-only models because the disclosure choice is not random. The sub-sample includes firms that deem segment equity an important piece of information and also use it for internal decision making. Therefore, the value relevance of segment equity is likely overstated in these models. Results, however, show that, even with this upward bias, equity does not provide much explanatory power incremental to segment earnings. Hence, we are not overly concerned about this sample bias. Moreover, the analysis of segment equity is rather supplementary to the earnings-only models.

- 15 This assumption seems reasonable as the application of the new standard is mandatory. However, if entities could use discretion to choose whether they comply with the new reporting rules or not (hence, self-select into the change or no-change group), the treatment would be endogenous. Yet, the auditor should ensure that a firm properly applies accounting rules.

- 15 There might be firms that already reported in line with the management approach and just coincidentally changed their internal reporting at the same time of IFRS 8 adoption. These firms would be falsely flagged as change firms. However, we have searched all annual reports for any signs that may indicate this and did not find anything.

- 15 We lose four observations in our treatment group and one observation in our control group due to missing spread data resulting in 24 treatment firms and 41 control firms. The magnitude of the difference, however, is still economically meaningful.