Extreme Uncertainty and Forward-looking Disclosure Properties

Abstract

This study investigates the effect of extreme uncertainty on disclosure behaviour by analyzing the quality and quantity of forward-looking disclosures during the global financial crisis and pre-crisis periods, controlling for other determinants of disclosure behaviour. Prior research has struggled to distinguish between the quality and quantity dimensions of forward-looking disclosures. Also, the impact of the recent financial crisis on these forward-looking disclosure attributes has not yet been examined systematically. We address this gap by exploiting the unique setting of German publicly traded firms. These firms must provide forward-looking information within their audited financial statements, although relevant regulation is sufficiently vague to allow great variation in the quality, scope and quantity of forward-looking disclosures actually observed. Using hand-collected data from 2005 to 2009, we provide evidence of a significantly negative association between crisis and disclosure quality. This finding is robust to several different disclosure quality proxies and regression specifications. In contrast, we find no negative significant relation between crisis and disclosure quantity; rather, there is evidence that reported volume increases during the crisis. Our results are consistent with extreme uncertainty, as occurring during times of crisis, negatively affecting the quality of voluntary disclosures, while firms maintain or increase disclosure quantity, ultimately diluting the information density of forward-looking disclosures.

Managers use forward-looking disclosures to communicate expectations about their firms' prospects, which assists investors with firm valuation (Beretta and Bozzolan, 2008). We analyze the effect of extreme uncertainty, as observed in the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008, on the quality and quantity of firms' forward-looking disclosures. Based on a sample of publicly traded German firms over the period 2005–2009, we find that the quality of forward-looking disclosures declines in the crisis, whereas disclosure q`uantity is not negatively affected. These results suggest that extreme uncertainty impairs the quality of firms' voluntary disclosures, but that firms obfuscate this decrease in quality by maintaining disclosure quantity, ultimately diluting the information density of forward-looking disclosures. Our findings shed new light on the determinants of forward-looking disclosures by considering the effect of extreme uncertainty and focusing on two distinct disclosure properties.

In Germany, forward-looking disclosures are published within the annual report, one of the most important sources of corporate information (Botosan, 1997, p. 331). German commercial law requires that publicly traded firms provide an audited forward-looking report on future developments, but lacks detailed prescriptions. This setting has several advantages for our study. First, forward-looking information provided by German public firms has characteristics of both mandatory and voluntary disclosure. Despite the legal mandate to provide a forward-looking report, guidance regarding its structure, the scope of reportable items, as well as forecast horizon, precision, and assumptions is vague. Therefore, whereas the legal requirement eliminates the potential concern of self-selection bias regarding whether to provide forward-looking disclosures at all, the vagueness of the requirements enables significant cross-sectional variation in the disclosure properties of interest. Second, mandatory audits of German forward-looking reports ensure a minimum level of reliability, which is important because market discipline, for example, in terms of litigation risk for provision of erroneous forecasts, may be weaker in Germany compared to other developed markets. Third, anecdotal evidence indicates that economic uncertainty affects the properties of forward-looking disclosures in Germany. During the recent crisis, Germany endured one of the most severe recessions, with GDP declining by 4.7% in 2009. During that period, the German Financial Reporting Enforcement Panel (FREP) sanctioned a number of deliberate omissions of required forward-looking disclosures (FREP, 2009).

We focus on information provided in firms' forward-looking reports, which are intended to assist users in assessing the firm's prospects (and, thus, firm value) by providing forecasts through the eyes of management. The current debate about disclosure overload (e.g., in the context of the IASB's Disclosure Initiative) 1 again indicates that disclosure quality and quantity are distinct properties. Forward-looking disclosure quality represents the ex ante usefulness of the disclosed forward-looking information for user's valuation decisions. It is driven by the scope of items forecasted (e.g., sales, earnings, etc.), as well as the qualitative characteristics of these individual forecasts, namely their ex ante precision, their forecast horizon, their economic direction relative to the firm's past performance, and the presence of related context and qualitative explanations. 2

Our disclosure quality measure, which is based on detailed content analysis of our sample firms' forward-looking reports, is intended to capture these aspects. Specifically, we apply a coding scheme to measure the extent to which the range of forecast items reported complies with the relevant disclosure standards under German GAAP. Disclosed forecasts are weighted using three qualitative forecast characteristics: (1) forecast horizon; (2) ex ante forecast precision; and (3) economic direction of future developments, whereas additional narrative explanatory items (e.g., major assumptions and forecasting methods) are coded dichotomously. This yields a weighted quality index, QUAL, which we use as our main disclosure quality construct. 3 In contrast, forward-looking disclosure quantity is merely the volume, or length, of the forward-looking report, without regard to the kind of information provided. Disclosure quantity (QUAN) is measured as forward-looking report word count.

Our study contributes to the managerial forecast literature in several ways. First, whereas most prior studies focus on disclosure ‘quality’, we analyze two distinct dimensions of forward-looking disclosure behaviour—quality and quantity—in terms of their determinants. Findings are robust to extensive sensitivity tests, including different specifications of our disclosure quality construct. Second, this paper is among the first to consider the effects of extreme uncertainty—as observed during the GFC of 2008—on these properties of forward-looking disclosures. Third, we go beyond specific forecast types (e.g., earnings forecasts) by considering a broad array of forward-looking information provided in audited German forward-looking reports. Notably, we also consider qualitative aspects of forward-looking report narratives, such as whether major assumptions and forecasting methods are described. In doing so, our measure of forward-looking disclosure quality goes beyond the quantitative forecast properties (such as ex ante precision) typically addressed in the management forecast literature. Finally, we analyze a large number of listed companies covering a five-year period of stable regulation. Our results are of potential interest for disclosure regulators and users of financial reporting information, as they indicate that extreme uncertainty can induce firms to reduce the information density of their forward-looking reports by maintaining quantity trends while decreasing the richness and precision of the information given.

1 Institutional Background

1.1 Regulation of German Forward-looking Reports

Under the German Commercial Code (GCC), public firms are required to supplement their consolidated IFRS financial statements with a group management report, a narrative similar to Management's Discussion & Analysis (MD&A) in US firms' 10-K filings. Forward-looking information has been a mandatory component within the group management report since 2005, the beginning of our analysis period. Section 315 GCC lists the mandatory contents of the group management report. With respect to forward-looking information, it requires as a minimum an assessment and discussion of the expected development of the group and its significant risks and opportunities, along with underlying assumptions.

However, the scope, structure, reportable items, time horizon of forecasts, assumptions, and other details of the forward-looking report are not regulated in detail by law. The private-sector Accounting Standards Committee of Germany's (ASCG) German Accounting Standard (GAS) No. 15 ‘Management Reporting’ provides a recommended framework for presenting the forward-looking report, 4 however, GASs are mere recommendations and are not strictly legally binding.

In practice, firms provide diverse types of information within their forward-looking reports, ranging from qualitative forecasts of financial statement items such as sales and earnings, to qualitative expectations regarding non-financial indicators. This makes the German forward-looking report a much more comprehensive type of disclosure compared to, for example, management earnings forecasts issued in press releases. Although in principle a mandatory disclosure, the vagueness of the GCC requirements leaves substantial room for discretion, in effect making the German forward-looking report a voluntary disclosure in terms of the quality, scope and quantity of information provided. The scope and heterogeneity of observed disclosures provides us with sufficient time-series and cross-sectional variation to analyze the determinants of disclosure behaviour. We study extreme uncertainty as experienced by firms in times of crisis.

1.2 Enforcement of Disclosure Requirements

Germany has a two-tier enforcement structure for financial reporting. As a first step, the private-sector FREP samples firms listed on the German regulated market for in-depth reviews of the group financial statements and management report. The FREP also takes action when concrete incidents come to its attention, for example, through whistle-blowing. When it detects a material misstatement, the FREP will recommend that the firm issue a restatement. If the firm refuses, the FREP will, as a second step, escalate the case and involve the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht—BaFin), which can ultimately force the firm to restate.

During our analysis period, the FREP frequently focused on forward-looking reports, noting several incidents of inadequate reporting. The number of errors in forward-looking reports increased considerably in 2008 compared with prior years. During the GFC, the FREP cited deliberate instances of omission of forward-looking information (FREP 2009). For example, Merck AG explicitly omitted any forecasts or qualitative statements concerning its future in its forward-looking report for 2008. The BaFin, backed by the Higher Regional Court in Frankfurt (OLG Frankfurt/M. 2009), required Merck's management to publish and rectify this error in the electronic German Federal Gazette. This case documents that, whereas German firms had significant incentives to reduce their forward-looking disclosure activities in the GFC, the German enforcement infrastructure prevents outright omissions of the entire required forward-looking report. Against this backdrop, we are interested in firms' discretionary forward-looking disclosure decisions when ‘no disclosure’ is not an option.

1.3 Impact of the Financial Crisis on German Firms

Our analysis is predicated on the expectation that firms alter their disclosure behaviour when facing extreme uncertainty, as is the case in times of crisis. The GFC severely affected the German economy, leading to the most severe recession since World War II, with a decrease in GDP by 4.7% in 2009. 5 Firms' economic perspectives became uncertain during 2008, which is reflected in statements like ‘in the financial year 2009, we will be confronted with unprecedented imponderables’ (Salzgitter, 2008, p. 158) or ‘towards the end of 2008 … the rapid pace of the economic downturn and uncertainty … make reliable forecasts extremely difficult, even for the near future’ (BMW, 2008, p. 69). However, few firms responded, as Merck did (see above), by omitting forward-looking disclosures entirely. More commonly, firms reduced disclosure quality and scope, while maintaining a relatively stable quantity in terms of word count—in effect diluting the information density of their forward-looking reports.

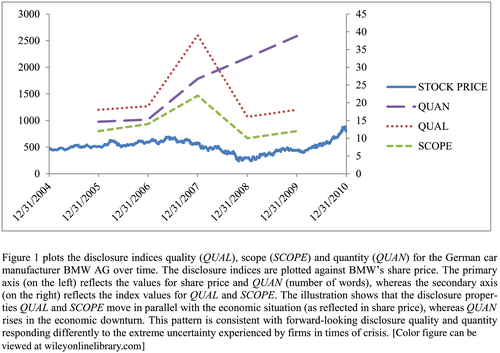

To illustrate, Figure 1 depicts BMW's quality, scope, and quantity of forward-looking disclosures against the development of stock price between 2004 and 2010. Quality and scope decrease dramatically in 2008, following BMW's stock price decline towards the end of 2008. In contrast, quantity rises steeply from 2006 through 2009. Only during 2009, do forward-looking disclosure quality and scope appear to be catching up with the economic recovery reflected in BMW's stock price. This example shows that crisis situations potentially affect forward-looking disclosure properties differently. This multifaceted nature of disclosure behaviour and its interaction with extreme uncertainty has thus far received little attention from researchers, and is at the center of this study

2 Related Literature and Hypotheses

2.1 Related Literature

Voluntary disclosure, or discretionary-based disclosure (Verrecchia 2001), is the provision of information in excess of mandatory requirements. When voluntary disclosure behaviour is modelled using game theory, the central premise is that an entity discloses favourable information and holds back unfavourable information (Dye, 2001). Companies are expected to engage in voluntary disclosure when the benefits of additional disclosure outweigh its costs (Malone et al., 1993), which include those related to information collection and processing (Foster, 1986), as well as competitive disadvantage (Prencipe, 2004; Verrecchia, 2001).

Providing forward-looking information might reduce agency conflicts between company insiders and other interest groups that arise due to information asymmetry (Healy and Palepu, 2001; Hossain et al., 1995), leading to reduced agency costs as well as political costs (Chavent et al., 2006) and costs of equity capital (Kristandl and Bontis, 2007). Company-specific forward-looking information is important to investors and analysts and helpful in forecasting, and its absence might force stakeholders to rely on other, less reliable information sources (Kieso and Weygandt, 1995). For the German setting, surveys show that the forward-looking report is considered among the most important sections of the management report (Kajüter et al., 2010; Prigge, 2006). Especially during unstable economic conditions, investors need relevant and reliable information for their decision making, as imprecise or absent disclosures cause distrust and attract the attention of regulators.

Prior forward-looking disclosure research mainly focuses on earnings forecasts. For example, Choi et al. (2010) examine earnings forecasts and their relation to forecast surprise and uncertainty. They provide evidence that ex ante forecast precision is higher with lower earnings volatility, a measure for uncertainty, and a lower forecast surprise. Additionally, they find that forecasts for bad news are less precise than those for good news. Ajinkya et al. (2005) find higher ex ante forecast precision of earnings forecasts for firms with a higher number of institutional owners. Baginski et al. (2004) examine why some companies explain their earnings forecasts. They provide evidence that larger firms in a less regulated environment are more likely to provide additional explanations accompanying earnings forecasts than smaller companies. They also find that explanations are more likely for bad news earnings forecasts than for good news. Clarkson et al. (1999) divide their sample into good news and bad news forecasts. They observe that good news firms increase (decrease) disclosures when they need external financing (when they face competitors entering the market). For bad news firms the disclosure extent is the opposite.

Few studies have examined the determinants of a broader type of forward-looking disclosure behaviour. Li (2010) examines the tone and content of forward-looking information in 10-K and 10-Q filings and its determinants. Using computer-based analyses of 140,000 filings, he finds that firms with better current performance, lower accruals, smaller size, lower market-to-book ratios, lower return volatility, lower MD&A Fog index and longer history are more likely to have more positive forward-looking reports. With regard to the determinants of forward-looking information quantity, Aljifri and Hossainey (2007) find significant associations with debt ratio and profitability in the UAE, while Celik et al. (2006) find capital structure, profitability, foreign investment, and ownership structure are significant determinants in Turkey. Hossain et al. (2005) find voluntary disclosure of prospective information is associated with investment opportunities for listed firms in New Zealand. Kent and Ung (2003) find that larger firms and those with less volatile earnings are more likely to provide earnings forecasts.

For German firms, Barth (2009) examines forward-looking reporting around the adoption of stricter regulation in Germany in 2005. Using a self-constructed index that weights reported items according to their importance elicited in a survey of auditors and financial analysts, she finds that disclosure quality increases over time, and that only firm size is a statistically significant explanatory factor (Barth, 2009). Using the same index, Barth and Beyhs (2010) analyze the forward-looking reports of 113 German companies between 2004 and 2009. They observe increasing disclosure quality until 2007, a decrease in 2008, and again an increase in 2009. In terms of forecast types, qualitative and comparative forecasts (point and range forecasts) increase in 2008 (2009). Knauer and Wömpener (2010) examine whether earnings and revenue projections disclosed in the forward-looking reports of German firms are subsequently met. Ex post accuracy for the period 2005–2007 is 38.8% for earnings forecasts and 41.0% for revenue forecasts. Nölte (2009) investigates the determinants of management forecasts for German DAX and MDAX companies. He provides evidence that a low percentage of intangible assets, low EPS volatility, low volatility of prior-year earnings, higher market-to-book ratio, and higher need for external financing drive more precise forecasts.

Overall, prior literature shows that voluntary forward-looking disclosure behaviour varies predictably with factors implied by theory. However, much prior research focuses on management forecasts of key performance indicators, such as earnings or revenues. We analyze a comprehensive range of items provided in German firms' forward-looking reports, which allows us to consider aspects of disclosure quality separately from disclosure quantity. Furthermore, we explicitly address the differential impact of extreme uncertainty in crisis times on these distinct dimensions of forward-looking disclosure behaviour.

2.2 Hypothesis Development

Extreme uncertainty, as in times of economic crisis, makes forecasting difficult (Choi et al., 2010; Lahiri and Sheng, 2010). During the 2008 GFC, German firms called for a temporary suspension of forward-looking reporting requirements. However, when the German financial accounting standard setter argued that such a waiver would unsettle the markets, it created an interesting problem for firms: how to comply with forward-looking reporting requirements in a situation where forecasts were perceived to be virtually impossible?

Lundholm and Van Winkle (2006; hereafter LVW) provide a theoretical framework that fits our setting. Consistent with key insights from the theoretical disclosure literature, the LVW framework assumes that managers, attempting to maximize stock price, provide disclosures to mitigate adverse selection caused by investors who, absent such disclosures, are sceptical about the firm's prospects. Absent frictions, the well-known unravelling result obtains: all firms but those with the worst possible news will provide full disclosure.

However, frictions can preclude this outcome. LVW groups these frictions into three categories: (1) management is not trying to maximize stock price (‘don't care’ friction); (2) disclosure costs (including, e.g., proprietary costs) are prohibitive (‘can't tell’ friction); and/or (3) management has no information to disclose (‘don't know’ friction). Regarding the latter of these frictions, LVW (p. 48) elaborate that managers may ‘know something with such great uncertainty’ that they are in effect precluded from disclosing this information. LVW also note that this ‘don't know’ friction is under-researched in the accounting literature.

We apply the LVW framework to our forward-looking disclosure setting to provide direct evidence on the ‘don't know’ friction, using control variables to control for ‘can't tell’ frictions. The extreme uncertainty caused by the (sudden) onset of the financial crisis represents an exogenous shock to the previous disclosure equilibrium, as it introduces, or aggravates, the ‘don't know’ friction. In a voluntary disclosure setting, we would expect firms to react by reducing their forward-looking disclosures—either (a) because the uncertainty truly precludes them from making sufficiently high-quality disclosures, or (b) because it provides a pretext for abstaining from disclosure without being pooled with ‘bad news’ firms.

We therefore predict that the onset of extreme uncertainty during the GFC, ceteris paribus, is associated with firms reducing the ex ante precision and horizon of their forecasts, with or without a reduction in the range of items reported, 6 decreasing the quality of forward-looking disclosures. 7 This leads to our first hypothesis, stated in alternative form:

H1.The disclosure quality in forward-looking reports is lower in crisis periods than in pre-crisis periods.

However, the forward-looking disclosures we study are not entirely voluntary. Interestingly, in our specific German setting, discontinuing forward-looking disclosure represents misreporting because some degree of forward-looking reporting is mandated by commercial law. As we argued in section 1, this is true even in situations of extreme uncertainty.

In this context, we consider the question what happens if firms ‘don't know’ (due to extreme uncertainty), but non-disclosure—‘can't tell’—is not an option (due to binding law). In terms of forward-looking disclosure quantity, the effect of extreme uncertainty is unclear ex ante. On the one hand, a reduction in the quality and scope of forecasts could lead to an equivalent reduction in volume narrated, our measure of disclosure quantity. On the other hand, if management worries that reduced forecast report volume could signal to the market that the firm is ‘flying blind’, it may hold constant (or increase) disclosure quantity, in effect diluting ‘information density per page’ of the forward-looking report. Anecdotal evidence in Figure 1 and prior descriptive studies (Knauer and Wömpener, 2010; Ruhwedel et al., 2009) are consistent with this expectation. Due to these conflicting predictions, we hypothesize, in alternative form:

H2.The disclosure quantity in forecast reports differs between crisis and pre-crisis periods.

3 Research Design and Sample

3.1 Model Specification

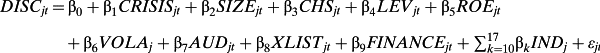

(1)

(1)-

- DISCjt

-

- captures two distinct dimensions of disclosure behaviour of firm j for year t: forward-looking disclosure quality (QUAL) and quantity (QUAN). QUAL is the absolute forward-looking disclosure quality index, and QUAN is the absolute forward-looking disclosure quantity index; 9

-

- CRISISjt

-

- is an indicator variable, equal to 1 if year t is a crisis year (2008), and 0 otherwise (2005–2007 and 2009); 10

-

- SIZEjt

-

- is the natural logarithm of firm j's total assets at the end of year t;

-

- CHSjt

-

- is firm j's fraction of equity owned by insiders at the end of year t;

-

- LEVjt

-

- is firm j's percentage of debt divided by total assets at the end of year t;

-

- ROEjt

-

- is firm j's percentage return on equity (net income before preferred dividends—preferred dividends/average of last year's and current year's common equity) at the end of year t;

-

- VOLAjt

-

- is firm j's variance of total shareholder return over the previous five years at the end of year t;

-

- AUDjt

-

- is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j is audited by a Big4 company for year t, and 0 otherwise;

-

- XLISTjt

-

- is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j is cross-listed in the US during year t (which includes the year of delisting, if any) 11, and 0 otherwise;

-

- FINANCEjt

-

- is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j makes a material debt or equity issuance in the year subsequent to year t, and 0 otherwise; 12

-

- INDj

-

- is a set of dummy variables indicating if firm j is operating in the basic materials, consumer goods, consumer services, industrials, information technology, pharma & healthcare, telecommunications, or utilities industry.

As we predict different crisis effects for the quality and quantity of forward-looking disclosure, we use two different dependent variables: quality (QUAL) and quantity (QUAN).

To test the relation between the properties of forward-looking disclosure behaviour and the existence of extreme uncertainty during times of crisis, we include the indicator variable CRISIS; thus, our main coefficient of interest is β1. Under , using QUAL as the dependent variable, we expect a negative coefficient. Under , using QUAN as the dependent variable, we refrain from making a signed prediction.

We then include variables documented in prior research to explain disclosure behaviour (for a review of pertinent studies, see, for example, Ahmed and Courtis, 1999; Healy and Palepu, 2001; Khlif and Souissi, 2010). We include SIZE, as disclosure quality and quantity should increase for larger firms, as a result of higher agency costs and information asymmetries due to more complex operations (Cooke, 1989), more and better internal information (Clarkson et al., 1994; Ahmed and Nicholls, 1994), higher and political costs (Buzby, 1975; Wallace and Naser, 1995). CHS captures information asymmetries between insiders and outside shareholders (Fama and Jensen, 1983; Jensen and Meckling, 1976), with firms having more insider shareholders less likely to voluntarily disclose. Leverage, LEV, captures debt-related agency costs (Jensen and Meckling, 1976); their effect on voluntary disclosures will depend on whether lenders are information insiders or outsiders. ROE is included as managers of more profitable firms are likely to provide more disclosures due to incentives to differentiate themselves from low-performing firms (Meek et al., 1995), compensation and job security concerns (Malone et al., 1993), as well as political costs (Cooke, 1989). We include VOLA, the variability of stock returns, as volatility should affect firms' ability to provide forecasts (Li, 2010; Waymire, 1985). Next, we include AUD, as large, skilled, and well-known audit firms may push companies to disclose more information (Firth, 1979; Singhvi and Desai, 1971; Craswell and Taylor, 1992). XLIST captures the more stringent disclosure requirements applying to firms cross-listed in the US. We then include FINANCE as firms intending to raise substantial amounts of new capital in the near future have incentive to be more forthcoming in terms of disclosures (Lang and Lundholm, 1993). Finally, we include IND to capture industry effects.

3.2 Dependent Variables

This subsection describes the two properties of forward-looking disclosures that we focus on, quality and quantity, and the related data collection procedures.

3.2.1 Disclosure quality

Whereas measuring quality objectively is challenging, 13 disclosure indices are a common approach (Ahmed and Courtis, 1999; Healy and Palepu, 2001). In prior literature, disclosure quality is measured by using either a self-constructed index (Botosan, 1997; Drake et al., 2009; Petersen and Plenborg, 2006) or an existing index (for example, AIMR or FAF; e.g., Lang and Lundholm, 1993). 14 In Germany, ‘Best Annual Report’ competitions provide disclosure scores for annual reports. 15 However, the subscore for the forward-looking report has too little detail for our purposes. We therefore develop our own index, as explained in detail below.

From the two alternative methods available (human coding and computer-based coding), we chose the former because our study deals with complex issues such as forecast direction and ex ante precision, which require in-depth understanding of context. Prior studies suggest that human coding is better-suited to capture the complexity of forward-looking reports, and to minimize misclassification, although computer-based methods are less labour intensive and therefore useful for large samples of easy-to-categorize text (Neuendorf, 2002; Weber, 1990; Beattie and Thompson, 2007). Li (2010) also finds poor results for the computer-based approach.

Our approach transforms forward-looking reports into quantitative scores following established content analysis coding procedures (Weber, 1990; Boyatzis, 1998). The coding scheme is based on requirements of the German Commercial Code as well as on GAS 15, which contains authoritative recommendations for forward-looking reporting in Germany. We supplement these authoritative sources with a literature review of prior forward-looking disclosure index studies (Barth, 2009; the Best Annual Report competition; Beretta and Bozzolan, 2008; Bozzolan et al., 2009; Robb et al., 2001), and established German accounting annotations (Beck'scher Bilanz-Kommentar, 2006; Münchener Kommentar zum HGB; Beck'sches Handbuch der Rechnungslegung, 2007; Kommentar zum HGB, 2009) to distill the interests and needs of different user groups. Furthermore, several checklists for forward-looking reports provided by different authors (Farr, 2006; Niemann, 2008; Tesch and Wißmann, 2009), as well as check lists used by the Big 4 audit firms, were consulted. This approach reduces subjectivity in the selection of forward-looking report items.

Following prior studies, we group items into three categories: economic environment, company-specific forecasts, and other disclosure items. Appendix A reports the list of disclosure index items and provides evidence on their incidence in our sample. The first category of items captures expected prospects of the overall economy and the industry. The second category considers company-specific forecasts such as revenues, earnings, or strategic measures. The third category encompasses other narrative information that affects the usefulness of the forecasts to investors, for example, an overall conclusion and major assumptions.

Prior studies have measured quality by constructing either unweighted or weighted indices (see reviews by Marston and Shrives, 1991; Ahmed and Courtis, 1999). Assuming that each item is equally important to the user, unweighted indices use binary coding (Cooke, 1992; Meek et al., 1995). Weighted indices can be distinguished according to the source of the weight, for example, surveys of experts (Naser and Nuseibeh, 2003; Oberdörster, 2009; Stanga, 1976; Singhvi and Desai, 1971), ex ante forecast precision, or ex post forecast accuracy. Ex ante precision corresponds to the exactness of the reported forecasts (e.g., point estimates versus range estimates), whereas ex post accuracy refers to the degree to which subsequent realizations confirm the forecasts. For example, Botosan (1997) uses a weighted index and assigns higher weights to quantitative information ‘because precise information is more useful and may enhance management's reporting reputation and credibility’ (Botosan, 1997, p. 334). The precision of forecasts is important, as it affects the degree to which investors can update their priors (Choi et al., 2010). Prior literature scores forecast precision on a range between non-disclosure and point estimates (Bozzolan and Mazzola, 2007; Wasser, 1976).

We use a weighted index to measure disclosure quality (QUAL). Whereas explanatory narrative items (e.g., discussion of major assumptions or description of forecast methods; see Category III in Appendix A) are coded dichotomously, forecasts (e.g., of earnings or dividends) are weighted according to the qualitative forecast properties of: (1) forecast horizon (not disclosed, one-year, two-year, intermediate-term, long-term 16); (2) ex ante forecast precision; and (3) economic direction of future developments (positive, negative, equal, not disclosed). 17 With regard to ex ante forecast precision, we follow Botosan (1997) and Kent and Ung (2003), putting more weight on quantitative information than on qualitative information. Specifically, we distinguish between point, bounded-range, open-range, minimum/maximum, comparative, and qualitative forecasts. 18 We assign 0 for non-disclosure and 5 for a bounded-range forecast, the underlying assumption being that the informational value of forecasts increases with a higher degree of precision (Bozzolan and Mazzola, 2007; Cahan et al., 2005; Morgan, 2008). 19

For a robustness test (reported in section 4.3.3), we use as an alternative quality measure an unweighted index, SCOPE, which dichotomously captures whether the items comprising QUAL (Appendix A) are present or absent in the forward-looking report. That is, the previously described weights are not relevant for SCOPE, as it deliberately measures the number of items disclosed independently from the qualitative forecast properties described above.

3.2.2 Disclosure quantity

The variable QUAN measures the total word count of the forward-looking report. Taking the number of words, rather than the number of pages or sentences, has the advantage that different layouts, font types and sizes, and so on, will not affect the results. QUAN captures the mere volume narrated, without regard to the scope of items presented, or the quality of forecasts.

3.2.3 Reliability and validity

To ensure the reliability of our content analysis (Krippendorff, 2004; Weber, 1990), all researchers involved in this study interacted in developing a clear and understandable coding scheme (Guthrie et al., 2004), in conducting a pre-test of 5% of the forward-looking reports, and in subsequently examining information where initial coding was not unanimous.

To achieve reproducibility, a second researcher assisted with the development of the coding scheme and the pretest, and also served as a consultant when classifications were unclear. Furthermore, to ensure a clear and understandable coding scheme, a third person with coding experience was involved for further advice on capturing the definitions, scores, and rules for conducting the coding. We are therefore confident that the coding scheme has a high degree of clarity and transparency.

Stability was ascertained by coding and recoding the data. The initial coding scheme was adapted according to the results of a pretest. Coding took place during the second half of 2009 for HDAX companies, and was repeated in early 2010, in order to detect any errors and resolve misunderstandings. The results were essentially the same in both cases, with only negligible differences, which were then adapted. SDAX reports were coded in the first half of 2010. Upon completion, a randomly drawn 5% of the sample was re-examined. Again, only insignificant coding differences were found, which indicates high stability.

To provide further assurance of construct validity, we examine correlations of our disclosure measures with disclosure quality scores used in a German annual report contest hosted, at the time, by the magazine Capital and supervised by Karlheinz Küting (deceased 2014) of the University of Saarbrücken. German annual report contest scores are regularly used to measure disclosure quality (see footnote 15). The Pearson (Spearman) correlation between the forward-looking report sub-index from the contest and our scope index (SCOPE, the closest match to the index used in the contest) is 0.58 (0.57), with a p-value of 0.01 (0.01). We thus conclude that our scope index measures forward-looking disclosure properties similar to those measured by a leading German annual report contest.

3.3 Sample

Our study spans the period 2005–2009. We begin in 2005 because the forward-looking report started being a mandatory component of the consolidated management report in that year. Our sample selection process (Table 1) starts with the 160 companies comprising the DAX, MDAX, TecDAX and SDAX indices within the Prime Standard, a segment of the Regulated Market at Frankfurt Stock Exchange, at the end of May 2009. We focus on these index constituents as they are subject to special listing requirements that ensure a minimum quality of financial reporting. Our sample covers the most important firms in their respective industries. Due to special reporting requirements, we drop banks and insurance companies. Insolvent firms, as well as firms with missing reports for the analyzed period, are also excluded. Furthermore, we exclude one company with a June fiscal year end. 20 This leads to a possible sample of 123 companies, yielding 615 firm-year observations over our five-year period.

| Firms | Firm years | |

|---|---|---|

| DAX constituents | 30 | 150 |

| MDAX constituents | 50 | 250 |

| TecDAX constituents | 30 | 150 |

| SDAX constituents | 50 | 250 |

| All index constituents | 160 | 800 |

| Financial and insurance institutions | –24 | –115 |

| Restructuring or insolvent | –5 | –25 |

| June fiscal-year end | –1 | –5 |

| Missing reports | –7 | –35 |

| Potential sample | 123 | 615 |

| Reduction due to fiscal year 2004/2005 | 0 | –11 |

| IPO in 2006, 2007, or 2008 | 0 | –24 |

| Change of reporting period | 0 | –1 |

| Failure to meet the going concern assumption | 0 | 8 |

| Final sample | 123 | 571 |

- Table 1 describes the sample selection process. We start with all firms included in the DAX, MDAX, TecDAX and SDAX indices of the Frankfurt Stock Exchange as of May 31, 2009. We exclude financial and insurance companies, companies that became insolvent or completely restructured/reorganized, that have a fiscal year end as of June 30, and that have missing reports. This leads to a potential maximum sample of 123 firms and 615 firm year observations (as our sample spans five years, 2005–2009). Firms with a non-calendar year end were excluded for the fiscal year 2004/2005, as forward-looking reports became mandatory only from the full year 2005 onward. Further reductions of the sample are due to IPOs in 2006, 2007 or 2008. A change of reporting period led to an exclusion of one firm-year observation. Due to extreme negative values for the variable profitability (ROE), eight observations were removed in order not to violate the going concern assumption. Altogether, the final sample is a panel that comprises 123 firms with 571 firm-year observations for our variables capturing disclosure attributes. (Note that we collect data on several control variables for 2010, as we control for future changes in sales as well as debt issuances and equity issuances.) Sample sizes in several of the subsequent tests are slightly smaller as we lose additional observations due to the use of lagged values for our disclosure variables, as well as missing observations for some control variables (see Table 3).

As forward-looking reports were not yet mandatory in 2004, we exclude 11 observations of non-calendar fiscal-year-end firms for the reporting period 2004–2005. Further reductions of the sample are due to IPOs in 2006, 2007, and 2008, and an incomplete fiscal year due to a change in reporting period (one firm-year observation). Due to extreme negative values for the variable profitability (ROE), we finally remove eight observations in order not to violate the going concern assumption. Altogether the final sample comprises 123 companies with 571 firm-year observations; this constitutes an unbalanced panel in which a given firm can appear up to five times.

4 Empirical Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistics

Panel A of Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for our forward-looking report quality and quantity (QUAL and QUAN) indices by year, as well as for our alternative, unweighted quality measure, SCOPE. Whereas QUAL and SCOPE increased through 2007, dipped in the crisis year of 2008, and then recovered in 2009, QUAN exhibits a monotonous increase throughout our five-year analysis period. We interpret the decreases in QUAL and SCOPE from 2007 to 2008, which are statistically and economically significant, 20 as initial evidence consistent with , which predicts that forward-looking disclosure quality is lower in crisis periods. More generally, and as predicted, our two distinct properties of forward-looking disclosure are affected differently by the crisis: whereas quality drops, quantity increases, as if unaffected by the crisis.

| Year | N | mean | std | min | p25 | med | p75 | max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward-looking disclosure quality (QUAL) | ||||||||

| 2005 | 96 | 25.45 | 16.15 | 3 | 13.5 | 23 | 32 | 79 |

| 2006 | 116 | 29.69 | 21.15 | 1 | 13.5 | 27.5 | 36.5 | 137 |

| 2007 | 122 | 31.89 | 20.56 | 1 | 19 | 28 | 40 | 135 |

| 2008 | 123 | 23.39 | 17.90 | 0 | 11 | 21 | 29 | 129 |

| 2009 | 122 | 28.12 | 16.76 | 5 | 17 | 26.75 | 34 | 95 |

| Forward-looking disclosure quantity (QUAN) | ||||||||

| 2005 | 96 | 1,155 | 847 | 203 | 526 | 925 | 1541 | 3,673 |

| 2006 | 116 | 1,258 | 901 | 171 | 677 | 994 | 1591 | 4,690 |

| 2007 | 122 | 1,447 | 980 | 138 | 754 | 1,242 | 1848 | 4,976 |

| 2008 | 123 | 1,584 | 1041 | 59 | 748 | 1,467 | 1983 | 5,166 |

| 2009 | 122 | 1,812 | 1112 | 138 | 1033 | 1,533 | 2259 | 5,010 |

| Forward-looking disclosure scope (SCOPE) | ||||||||

| 2005 | 96 | 14.40 | 8.18 | 1 | 8 | 13 | 19.5 | 38 |

| 2006 | 116 | 16.60 | 10.01 | 1 | 9 | 16 | 21 | 48 |

| 2007 | 122 | 18.04 | 9.77 | 1 | 13 | 17 | 22 | 50 |

| 2008 | 123 | 14.54 | 9.25 | 0 | 8 | 13 | 19 | 51 |

| 2009 | 122 | 16.63 | 8.60 | 1 | 11 | 15.5 | 21 | 52 |

- Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for the forward-looking disclosure indices QUAL, QUAN, and SCOPE per year. QUAL is the absolute disclosure quality index; QUAN is the absolute disclosure quantity index; and SCOPE is the absolute disclosure scope index. All three indices are explained in detail in section 3.2, along with Appendices A and B.

Further descriptive statistics for the dependent and all independent variables are displayed in Table 3. Focusing now on the independent variables, insider ownership (CHS) has a mean (median) value of 0.35 (0.33), suggesting that a significant proportion of share ownership in our German firms is held by insiders. The mean leverage ratio of 22% indicates a relatively low proportion of total assets being funded by debt. The average 14% ROE shows German companies have generated a healthy return to shareholders, but the volatility of some of the returns (VOLA) is high, with mean 0.66, standard deviation 2.38, and extreme values ranging up to a maximum of 26.09. The mean value of 0.79 for AUD shows that 451 out of 571 firm-year observations employed a Big4 audit firm. About 9% of observations pertain to years in which the firm is cross-listed in the US, and about 30% of the observations relate to firms raising material amounts of debt or equity in the subsequent year. Regarding the incidence of extreme uncertainty, the mean of 0.21 for CRISIS indicates that 21% of our firm-year observations relate to the crisis year of 2008, whereas mean SALES_DECL indicates that 12% of observations pertain to years followed by material sales declines in the subsequent year. Finally, the mean values for our industry indicator variables show that the largest portion of observations (41%) comes from industrial firms, with consumer goods (15%) a distant second.

| N | mean | std | min | p25 | med | p75 | max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||||||||

| Main tests | ||||||||

| QUAL | 571 | 27.9 | 18.9 | 0.0 | 14.0 | 25.0 | 35.0 | 137.0 |

| QUAN | 571 | 1,473 | 1,014 | 59 | 712 | 1,216 | 1905 | 5,166 |

| Sensitivity tests | ||||||||

| SCOPE | 571 | 16.2 | 9.3 | 0.0 | 9.0 | 15.0 | 21.0 | 52.00 |

| Independent variables | ||||||||

| SIZE | 571 | 14.49 | 1.86 | 10.50 | 13.08 | 14.24 | 15.61 | 19.38 |

| CHS | 542 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.97 |

| LEV | 571 | 21.74 | 15.56 | 0.00 | 9.70 | 19.86 | 32.32 | 71.97 |

| ROE | 571 | 13.94 | 15.81 | –47.24 | 7.13 | 14.13 | 22.42 | 98.67 |

| VOLA | 465 | 0.66 | 2.38 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 26.09 |

| AUD | 571 | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| XLIST | 571 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| FINANCE | 571 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| CRISIS | 571 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| SALES_DECL | 571 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| BAMA | 571 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| COGO | 571 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| COSE | 571 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| INDU | 571 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| IT | 571 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| PHHC | 571 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| TEL | 571 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| UTIL | 571 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

- Table 3 presents descriptive statistics for the dependent and independent variables. The number of observations for CHS and VOLA deviates from those in the final sample of Table 1 due to missing values for these variables. QUAL is the absolute disclosure quality index; QUAN is the absolute disclosure quantity index; and SCOPE is the absolute disclosure scope index. All three indices are explained in detail in section 3.2, along with Appendices A and B. SIZE is the natural logarithm of total assets; CHS is the fraction of equity owned by the insiders to all equity of the firm; LEV is the percentage of total debt divided by total assets; ROE equals percentage return on equity ((net income before preferred dividends—preferred dividend requirement)/average of last year's and current year's common equity); VOLA is the variance of total shareholder return over the last five years; AUD is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm is audited by a Big 4 audit firm, and 0 otherwise; XLIST is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j is cross-listed in the US during year t, and 0 otherwise; FINANCE is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j makes a material debt or equity issuance in the year subsequent to year t, and 0 otherwise; CRISIS is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the respective observation is from the crisis year 2008, and 0 otherwise; SALES_DECL is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j experiences a decline in sales of 10% or more in year t + 1, and 0 otherwise; and BAMA, COGO, COSE, INDU, IT, PHHC, TEL, and UTIL are indicator variables representing the basic materials, consumer goods, consumer services, industrials, information technology, pharma & healthcare, telecommunications, and utilities industries, respectively.

Table 4 displays Pearson correlations among the dependent and independent variables. Forward-looking disclosure quality (QUAL) and quantity (QUAN) are positively and significantly correlated (coefficient = .56). However, their correlations with our measures of extreme uncertainty are very different: Whereas QUAL correlates negatively and significantly with the two crisis indicators: CRISIS (coefficient = –.12) and SALES_DECL (coefficient = –.11), and CRISIS and SALES_DECL are correlated at 0.47 (p-value = 0.00), there is no significant correlation for QUAN. Note also that the two alternative disclosure quality measures QUAL and SCOPE exhibit a high positive correlation (coefficient = 0.92; p-value = 0.00) as expected, as both indices reflect the same items, differing only in terms of weighting (see section 3.2.1).

| QUAL | QUAN | SCOPE | SIZE | CHS | LEV | ROE | VOLA | AUD | XLIST | FINANCE | CRISIS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QUAN |

0.56*** |

|||||||||||

|

(0.000) |

||||||||||||

| SCOPE |

0.92*** |

0.63*** |

||||||||||

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

|||||||||||

| SIZE |

0.20*** |

0.38*** |

0.30*** |

|||||||||

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

||||||||||

| CHS |

–0.07 |

–0.16*** |

–0.06 |

–0.10 |

||||||||

|

(0.145) |

(0.000) |

(0.151) |

(0.019) |

|||||||||

| LEV |

0.03 |

0.15*** |

0.04 |

0.32*** |

–0.05 |

|||||||

|

(0.544) |

(0.001) |

(0.484) |

(0.000) |

(0.218) |

||||||||

| ROE |

–0.01 |

–0.13*** |

–0.03 |

–0.08* |

0.11** |

–0.12*** |

||||||

|

(0.272) |

(0.005) |

(0.302) |

(0.092) |

(0.019) |

(0.003) |

|||||||

| VOLA |

–0.14*** |

–0.11** |

–0.16*** |

–0.17*** |

–0.06 |

–0.04 |

0.03 |

|||||

|

(0.001) |

(0.020) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.192) |

(0.606) |

(0.458) |

||||||

| AUD |

0.07* |

0.16*** |

0.18*** |

0.38*** |

–0.07* |

0.09** |

–0.10** |

–0.02 |

||||

|

(0.087) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.085) |

(0.053) |

(0.031) |

(0.554) |

|||||

| XLIST |

0.09 |

0.15*** |

0.10** |

0.29*** |

–0.25*** |

–0.03 |

–0.03 |

–0.07 |

0.16*** |

|||

|

(0.028) |

(0.000) |

(0.014) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.463) |

(0.503) |

(0.113) |

(0.000) |

||||

| FINANCE |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.04 |

0.062 |

–0.01 |

–0.14*** |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.03 |

–0.04 |

||

|

(0.783) |

(0.934) |

(0.354) |

(0.051) |

(0.722) |

(0.002) |

(0.390) |

(0.173) |

(0.501) |

(0.448) |

|||

| CRISIS |

–0.12*** |

0.06 |

–0.08** |

0.03 |

0.04 |

0.05 |

–0.32 |

0.02 |

–0.00 |

–0.04 |

0.03 |

|

|

(0.004) |

(0.147) |

(0.035) |

(0.511) |

(0.411) |

(0.265) |

(0.439) |

(0.751) |

(0.974) |

(0.344) |

(0.503) |

||

| SALES_DECL |

–0.11*** |

0.05 |

–0.06 |

0.03 |

–0.09** |

–0.01 |

–0.05 |

–0.03 |

0.02 |

–0.04 |

0.03 |

0.47*** |

| (0.007) | (0.269) | (0.133) | (0.458) | (0.053) | (0.934) | (0.255) | (0.390) | (0.750) | (0.344) | (0.372) | (0.000) |

- Table 4 presents Pearson correlation coefficients between the dependent and independent variables, with p-values in parentheses. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The definitions of the dependent and independent variables are as follows: QUAL is the absolute disclosure quality index; QUAN is the absolute disclosure quantity index; and SCOPE is the absolute disclosure scope index. All three indices are explained in detail in section 3.2, along with Appendices A and B. SIZE is the natural logarithm of total assets; CHS is the fraction of equity owned by the insiders to all equity of the firm; LEV is the percentage of total debt divided by total assets; ROE equals percentage return on equity ((net income before preferred dividends—preferred dividend requirement)/average of last year's and current year's common equity); VOLA is the variance of total shareholder return over the last five years; AUD is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm is audited by a Big 4 audit firm, and 0 otherwise; XLIST is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j is cross-listed in the US during year t, and 0 otherwise; FINANCE is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j makes a material debt or equity issuance in the year subsequent to year t, and 0 otherwise; CRISIS is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the respective observation is from the crisis year 2008, and 0 otherwise; SALES_DECL is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j experiences a decline in sales of 10% or more in year t + 1, and 0 otherwise.

Furthermore, QUAL shows significantly positive (negative) correlations with firm SIZE and AUD (VOLA), indicating that higher (lower) forward-looking disclosure quality levels are associated with larger firms and Big 4 audit firms (stock price volatility). In contrast, whereas QUAN does not appear related to the crisis and financing indicators, it shows statistically significant correlations with all other variables. Among the independent variables, the highest correlation is between SIZE and AUD (0.38), indicating that multicollinearity is not a concern.

4.2 Main Results

We present panel regression results for Equation 1 in Table 5. 18 We first examine the determinants of forward-looking disclosure quality using QUAL as the dependent variable. 19 Whereas Model (1) presents baseline results, Model (2) provides our main test of H1 regarding the influence of extreme uncertainty on forward-looking disclosure quality. Models (3) and (4) then consider QUAN as the dependent variable, testing .

| DV = DISCL | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | DISCL = QUAL (N = 442) | DISCL = QUAN (N = 442) | ||

| SIZE | 1.058 | 1.577* | 235.91*** | 222.60*** |

|

(1.26) |

(1.89) |

(4.56) |

(4.43) |

|

| CHS | –4.581 | –2.927 | 347.88 | 305.27 |

|

(–0.93) |

(–0.62) |

(1.44) |

(–1.25) |

|

| LEV | –0.053 | –0.030 | 4.953 | 4.472 |

|

(–0.71) |

(–0.41) |

(1.25) |

(1.11) |

|

| ROE | 0.080* | 0.082* | –5.485*** | –5.535*** |

|

(1.74) |

(1.75) |

(–2.79) |

(–2.77) |

|

| VOLA | –0.392*** | –0.350*** | –7.842 | –8.688 |

|

(–2.93) |

(–2.51) |

(–1.51) |

(–1.57) |

|

| AUD | 2.685 | 2.185 | 108.56 | 120.96 |

|

(0.74) |

(0.60) |

(0.67) |

(0.76) |

|

| XLIST | 2.069 | 0.270 | –191.11 | –148.18 |

|

(0.42) |

(0.05) |

(–0.89) |

(–0.71) |

|

| FINANCE | –0.116 | 0.170 | 68.163 | 61.689 |

|

(–0.09) |

(0.13) |

(1.17) |

(1.08) |

|

| CRISIS | –5.456*** | 116.076** | ||

|

(–4.90) |

(2.29) |

|||

| Intercept | 20.695 | 12.385 | –2396.39*** | –2.181.10** |

|

(1.38) |

(0.83) |

(–2.64) |

(–2.45) |

|

| Industry effects | included | included | ||

| Overall R2 | 0.069 | 0.082 | 0.183 | 0.226 |

- Table 5 presents random-effects panel regressions of Equation (1) for our two measures of forward-looking disclosure behaviour and their determinants. We present regression coefficients with z-statistics in parentheses. The standard errors are robust to heteroscedasticity. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The definitions of the dependent and independent variables are as follows: DISC (disclosure) refers to QUAL or QUAN, respectively. QUAL is the absolute disclosure quality index; and QUAN is the absolute disclosure quantity index. Both indices are explained in detail in section 3.2 along with Appendices A and B. SIZE is the natural logarithm of total assets; CHS is the fraction of equity owned by the insiders to all equity of the firm; LEV is the percentage of total debt divided by total assets; ROE equals percentage return on equity ((net income before preferred dividends—preferred dividend requirement)/average of last year's and current year's common equity); VOLA is the variance of total shareholder return over the last five years; AUD is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm is audited by a Big 4 audit firm, and 0 otherwise; XLIST is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j is cross-listed in the U.S. during year t, and 0 otherwise; FINANCE is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j makes a material debt or equity issuance in the year subsequent to year t, and 0 otherwise; and CRISIS is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the respective observation is from the crisis year 2008, and 0 otherwise.

Regarding disclosure quality (QUAL), results for Model (1) show that QUAL is positively associated with ROE (coefficient = 0.080), and that this association is statistically significant (z-statistic = 1.74). The volatility of stock returns (VOLA) has a negatively significant association with QUAL (coefficient = –0.392; z-statistic = –2.93). In the base model, no other variables are significant.

Turning to our test of , the coefficient on CRISIS in Model (2) is significantly negative as predicted (coefficient = –5.46; z-statistic = –4.90), indicating that, during the crisis year of 2008, forward-looking disclosure quality scores were about six points lower, on average, than during the pre-crisis periods. The control variables are virtually unchanged in direction and significance levels (with only SIZE becoming significantly positive). The multivariate panel regression thus supports H1, confirming our insight from the univariate analysis that, controlling for other known influencing factors, extreme uncertainty as experienced during a crisis period is associated with lower forward-looking disclosure quality. This effect is economically meaningful, reflecting a drop in QUAL of about 20% during the crisis period compared to non-crisis periods. As discussed in section 4.5 below, this drop reflects a combination of forecast items omitted as well as less precise forecasts and forecasts over shorter time horizons, likely diminishing forward-looking report usefulness.

Turning to forward-looking disclosure quantity, the Model (3) baseline results show that QUAN is positively associated with SIZE (coefficient = 253.91, z-statistic = 4.56), whereas the previous negative association with VOLA is not found for QUAN. The association with ROE is now negative and significant (coefficient = –5.49; z-statistic = –2.79), whereas it was positive for QUAL; this suggests that profitable firms have lower incentive to provide large volumes of narrative relative to substantive information content. Turning to our test of in Model (4), we find a statistically significant positive association between CRISIS and QUAN (coefficient = 116.08; z-statistic = 2.29), corroborating the univariate evidence (Table 2) that reported mean volume increases by about 8%, although quality drops, in the crisis.

Taken together, these tests confirm our expectation that extreme uncertainty in crisis situations negatively impacts the quality () of forward-looking disclosures in the German market. We also find support for the notion that this quality decline is not accompanied by a decline in quantity; to the contrary, the observed increase in disclosure volume is consistent with firms concealing the decrease in disclosure quality by increasing disclosure volume, or quantity (), eventually diluting information density per unit of disclosure.

4.3 Sensitivity Analysis

This subsection reports sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results to: (a) different regression estimators; (b) the effect of lagged values of the dependent variables; (c) alternative specifications of our quality measure, QUAL; and (d) alternative specifications of the independent variable, CRISIS.

4.3.1 Pooled OLS and fixed effects estimation

Our inferences regarding and are unchanged when we repeat these tests using pooled OLS regression (not tabulated). 19 Specifically, in a regression using QUAL to reassess , the coefficient on CRISIS is –5.60 (t-statistic = –4.97). For , we find the coefficient on CRISIS to be 167.68 (t-statistic = 3.26) in a regression using QUAN. Furthermore, the results for are robust to fixed-effects estimation (not tabulated): in a regression using QUAL, the coefficient on CRISIS is –5.63 (t-statistic = –4.99), supporting . Regarding QUAN, the effect of CRISIS is insignificant (coefficient = 76.30; t-statistic = 1.48), consistent with no significant crisis effect on disclosure volume. Overall, we continue to conclude that extreme uncertainty as observed in crisis times reduces the quality of forward-looking reports, whereas it does not have that effect on disclosure quantity.

4.3.2 Effect of lagged values of the dependent variables

To explicitly test whether a firm's prior-period forward-looking reporting behaviour influences its present reporting, we introduce lagged values of our three disclosure indices into the models. Panel A of Table 6 corroborates Table 2 in documenting high year-over-year stickiness of QUAN and, to a lesser degree, QUAL, evidenced by high correlations between current and lagged values. Panel B shows highly significant positive coefficients on the lagged dependent variables, consistent with the univariate correlations. The coefficient on our variable of interest, CRISIS, remains significantly negative for QUAL (coefficient = –11.73; z-statistic = –7.04), which is again consistent with H1. Regarding , the coefficient on CRISIS in the regression explaining QUAN becomes insignificant, which suggests no significant impact of extreme uncertainty on disclosure quantity. Overall, introducing lagged dependent variables into the models does not materially alter our inferences of extreme uncertainty leading to reduced forward-looking disclosure quality while not reducing quantity.

| Panel A: Pearson correlations between dependent variables and lagged dependent variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QUAL | QUAL_L | QUAN | QUAN_L | |

| QUAL | 1 | |||

| QUAL_L | 0.7755*** | 1 | ||

| QUAN | 0.5596*** | 0.5054*** | 1 | |

| QUAN_L | 0.5194*** | 0.5726*** | 0.8703*** | 1 |

| Panel B: Regression analysis using lagged dependent variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| DV = DISCL | Model (5) | Model (6) |

| Variable | DISCL = QUAL (N = 442) | DISCL = QUAN (N = 442) |

| SIZE | 0.233 | 28.555** |

|

(0.81) |

(2.01) |

|

| CHS | 0.340 | –29.273 |

|

(0.14) |

(–0.30) |

|

| LEV | –0.002 | 0.764 |

|

(–0.07) |

(0.44) |

|

| ROE | –0.017 | –3.019* |

|

(–0.48) |

(–1.89) |

|

| VOLA | 0.109 | 9.909 |

|

(0.74) |

(0.83) |

|

| AUD | –1.765 | –47.55 |

|

(–1.14) |

(–0.77) |

|

| XLIST | 3.119 | 168.312** |

|

(1.36) |

(2.41) |

|

| FINANCE | 1.925 | 184.548** |

|

(1.34) |

(2.55) |

|

| CRISIS | –11.733*** | –50.277 |

|

(–7.04) |

(–0.69) |

|

| QUAL_L | 0.829*** | |

|

(18.33) |

||

| QUAN_L | 0.908*** | |

|

(28.92) |

||

| Intercept | 4.108 | 22.200 |

|

(0.65) |

(0.09) |

|

| Industry effects | included | included |

| Overall R2 | 0.700 | 0.790 |

- Panel A of Table 6 presents Pearson correlations between the contemporaneous and lagged dependent variables. Panel B displays random-effects panel regression results of an augmented Equation (1) similar to Table 5, but now additionally including lagged values of our dependent variables, i.e., our two measures of forward-looking disclosure behaviour. Panel B reports coefficients, with z-statistics in parentheses. Standard errors are robust to heteroscedasticity. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The number of observations is lower than that in Table 1 (final sample) due to missing values for CHS and VOLA as well as QUAL_L, SCOPE_L, and QUAN_L in the first year of analysis. The definitions of the dependent and independent variables are as follows: DISC (disclosure) refers to QUAL, SCOPE, or QUAN, respectively. QUAL is the absolute disclosure quality index; SCOPE is the absolute disclosure scope index; QUAN is the absolute disclosure quantity index (all three indices are explained in detail in section 3.2 along with Appendices A and B); QUAL_L is the absolute disclosure quality score for year t–1; SCOPE_L is the absolute disclosure scope score for year t–1; QUAN_L is the absolute disclosure quantity score for year t–1; SIZE is the natural logarithm of total assets; CHS is the fraction of equity owned by the insiders to all equity of the firm; LEV is the percentage of total debt divided by total assets; ROE equals percentage return on equity ((net income before preferred dividends—preferred dividend requirement)/average of last year's and current year's common equity); VOLA is the variance of total shareholder return over the last five years; AUD is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm is audited by a Big 4 audit firm, and 0 otherwise; XLIST is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j is cross-listed in the US during year t, and 0 otherwise; FINANCE is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j makes a material debt or equity issuance in the year subsequent to year t, and 0 otherwise; and CRISIS is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the respective observation is from the crisis year 2008, and 0 otherwise.

4.3.3 Different specifications of disclosure quality

Our main test of relies on QUAL, our weighted disclosure quality index. In order to ensure that subjective weighting procedures are not driving our results, we reassess using SCOPE, our unweighted disclosure quality index described at the end of section 3.2.1. We argue that the degree to which the crisis affects disclosure scope depends on the degree to which firms reduce the range of items on which forecasts are being disclosed. In the extreme, firms reduce the ex ante precision and horizon of their forecasts, leaving the scope of forecasted items unchanged. For example, a firm could continue providing earnings, sales, and R&D budget forecasts, but substitute vague qualitative statements for the previous quantitative point forecasts. This type of behaviour would reduce forward-looking disclosure quality, QUAL, whereas it would leave forward-looking disclosure scope, SCOPE, unaffected. Therefore, we expect that SCOPE also goes down in crisis times, but does so to a lesser degree than QUAL.

Model (7) in Table 7 presents the findings. Overall, the unweighted disclosure quality measure, SCOPE, performs similarly to QUAL, our weighted quality proxy (refer to Table 5). Specifically, SIZE, ROE, and VOLA are still significant, whereas the other control variables are not; this indicates that SCOPE and QUAL are influenced by similar factors. Turning to our experimental variable, CRISIS has the predicted significantly negative coefficient (–1.986; z-statistic = –3.38), indicating a negative effect of extreme uncertainty on forward-looking disclosure scope; this finding supports H1. Note that the coefficient on CRISIS in the QUAL regression (Model 1 in Table 5) is absolutely larger (–5.46) than that found here for SCOPE (–1.986), suggesting that extreme uncertainty as experienced in crisis times is associated with reductions in both the quality and scope of forward-looking disclosures, but that the effect on scope is less strong. 19

| Variable | Model (7) | Model (8) | Model (9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV = SCOPE (N = 442) | DISCL = QUAL (N = 442) | DISCL = QUAN (N = 442) | |

| SIZE | 1.232*** | 1.571* | 239.37*** |

|

(3.20) |

(1.94) |

(4.43) |

|

| CHS | 0.67 | –5.421 | 345.90 |

|

(0.30) |

(–1.18) |

(1.42) |

|

| LEV | –0.020 | –0.057 | 4.93 |

|

(–0.53) |

(–0.79) |

(1.24) |

|

| ROE | 0.041* | 0.082* | –5.47*** |

|

(1.72) |

(1.88) |

(–2.77) |

|

| VOLA | –0.257*** | –0.397*** | –7.86 |

|

(–4.59) |

(–3.09) |

(–1.52) |

|

| AUD | 1.296 | 2.493 | 107.41 |

|

(0.90) |

(0.63) |

(0.66) |

|

| XLIST | 0.540 | 0.338 | –201.55 |

|

(0.30) |

(0.07) |

(–0.94) |

|

| FINANCE | 0.148 | 0.398 | 70.84 |

|

(0.24) |

(0.31) |

(1.21) |

|

| CRISIS | –1.986*** | ||

|

–3.38 |

|||

| SALES_DECL | –7.159*** | –35.83 | |

|

(–4.21) |

(–0.58) |

||

| Intercept | –0.243 | 12.742 | –2,451.79*** |

|

(–0.04) |

(0.89) |

(–2.73) |

|

| Industry effects | included | included | included |

| Overall R2 | 0.142 | 0.084 | 0.182 |

- Table 7 presents random-effects panel regressions of variants of Equation (1). Model (7) uses SCOPE, our unweighted disclosure quality index (explained in section 3.2) as dependent variable. Models (8) and (9) reassess Models (2) and (4), respectively (Table 5), using a firm-specific crisis indicator, SALES_DECL, to replace CRISIS. SALES_DECL is equal to 1 if firm j experiences a decline in sales of 10% or more in year t + 1, and 0 otherwise. We present regression coefficients with z-statistics in parentheses. The standard errors are robust to heteroscedasticity. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. QUAL and QUAN are defined as previously. SIZE is the natural logarithm of total assets; CHS is the fraction of equity owned by the insiders to all equity of the firm; LEV is the percentage of total debt divided by total assets; ROE equals percentage return on equity ((net income before preferred dividends—preferred dividend requirement)/average of last year's and current year's common equity); VOLA is the variance of total shareholder return over the last five years; AUD is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm is audited by a Big 4 audit firm, and 0 otherwise; XLIST is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j is cross-listed in the US during year t, and 0 otherwise; FINANCE is an indicator variable equal to 1 if firm j makes a material debt or equity issuance in the year subsequent to year t, and 0 otherwise; and CRISIS is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the respective observation is from the crisis year 2008, and 0 otherwise.

To further test the robustness of our tests of H1, we use two other alternative specifications of QUAL. First, as there is no unanimous preference in the literature for point versus range forecasts (refer to section 3.2), we reverse the weights for these forecasts relative to those adopted in QUAL. Results (not tabulated) are qualitatively unchanged. Second, we restrict our disclosure quality index to quantified firm-specific information by excluding category I and III items as well as non-quantified category II items (refer to Appendix A). Again, inferences are unchanged. Specifically, the coefficient on CRISIS is negative as predicted and highly significant (coefficient = –5.640; t-statistic = –2.65).

4.3.4 Different specifications of the extreme uncertainty indicator

The effect of the GFC was likely felt in Germany beyond 2008, and different firms were affected at different times. We therefore test the robustness of our results to widening the crisis period captured in our crisis indicator. We re-run our tests using a new CRISIS dummy that equals 1 for the years 2008 and 2009, and 0 for the years 2005–2007 (not tabulated). 19 The significantly negative association of CRISIS with QUAL (Model 1) is qualitatively unchanged (coefficient = –3.93; z-statistic = –3.72). This is despite our descriptive evidence, which shows a marked recovery of QUAL in 2009 relative to 2008. Turning to disclosure quantity, the extended CRISIS dummy has a significantly positive association with QUAN (coefficient = 363.96; z-statistic = 6.09), which again is in line with our main results (Table 5) as well as descriptive evidence of monotonously increasing mean and median QUAN values.

We further address the concern that extreme uncertainty is not adequately captured by a crisis indicator that switches on for all firms at the same time. We therefore define SALES_DECL, an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm experiences a decline in sales of 10% or more in the subsequent year (and 0 otherwise) to capture firm-specific turbulence in the subsequent year that should affect forecasting uncertainty in the current year. Substituting SALES_DECL for CRISIS allows us to capture firm-specific extreme uncertainty, which can be related or unrelated to the onset of the GFC. 20 Descriptive evidence reported in Table 3 shows that 12% of firm-year observations have sales declines of 10% or more in the subsequent year, compared to 21% of firms being ‘crisis observations’ from the year 2008. Sales declines are heavily concentrated in 2008 (43% of firms), with less than 6% of firms affected in each of the other years under study. Furthermore, the correlation coefficient between SALES_DECL and CRISIS (0.47) is highly significant (p-value = 0.00; see Table 4). These results suggest that SALES_DECL is a more restrictive, but similar, uncertainty proxy than CRISIS.

Regression tests of and are reported in Models (8) and (9) of Table 7. Results are again consistent with our main inference of extreme uncertainty (SALES_DECL) leading to reduced forward-looking disclosure quality (QUAL; coefficient on CRISIS = –7.16; z-statistic = –4.21), while not reducing quantity (QUAN; coefficient on CRISIS = –35.83; z-statistic = 0.58). 21

4.5 Discussion

Our regression results suggest that extreme uncertainty in crisis situations reduces the quality of forward-looking disclosures reported by German firms. However, this quality decline is not accompanied by a reduction in quantity. What are the visible changes in firms' forward-looking reports during the crisis that underlie the significant drop in quality?

We turn to Appendix A, which aggregates our disclosure items into subcategories, and reports the average number of firms providing these by year. Whereas the frequency of macro-economic or industry-level items, which firms tend to source externally, increases from 2007 to 2008, it is primarily quantitative firm-specific forecasts that tend to be discontinued. For example, profitability forecasts, dividend forecasts, and segment earnings forecasts go down by around 45% each. Overall, the mean number of firm-specific quantitative variables disclosed (untabulated) increases from 5.2 in 2005 to 6.9 in 2007 (2006: 6.2), dropping back down to 5.2 in 2008 (2009: 6.0). These findings are consistent with firms omitting those disclosures most affected by extreme uncertainty, while retaining those that rely less on predictive ability.

Regarding the items that firms do forecast, we see reductions in the important quality aspects of ex ante precision, forecast horizon, and economic direction (untabulated). Precisely, over 2008 to 2007, the ex ante precision score drops from a mean of 18.9 points to 13.0 points (a 31% reduction), the forecast horizon score goes down from 5.3 to 3.8 (–27%), and the economic direction score deteriorates from 2.0 to 1.1 (–42%).

This evidence suggests that the drop in disclosure quality observed during the crisis reflects fewer firm-specific items being disclosed, as well as lower precision and shorter horizons relating to the items that firms do continue forecasting. This pattern is consistent with our expectation of extreme uncertainty affecting firms' predictive capabilities, but mandatory disclosure requirements making it difficult for them to noticeably reduce the range of items reported, and the volume narrated. Consequently, the crisis situation negatively affects the information density and thereby, we would argue, usefulness of forward-looking disclosure.

5 Conclusion

The aim of this paper is to examine the effect of extreme uncertainty on two distinct properties of forward-looking disclosure: quality and quantity. Observing a sample of German listed firms over a five-year period including the height of the 2008 crisis, we find that, controlling for other factors known to influence voluntary disclosure behaviour, forward-looking disclosure quality decreased significantly during the crisis, whereas disclosure quantity trended upward. This evidence is consistent with extreme uncertainty, as occurring during times of crisis, negatively affecting the quality of voluntary disclosures, whereas firms maintain or increase disclosure quantity, diluting the information density of disclosures. These results are robust to a number of alternative specifications, including different quality measures and crisis indicators.

This study contributes to prior literature on the determinants of voluntary disclosure behaviour in general, and management forecasts in particular, by shedding light on the effect of extreme uncertainty on two distinct properties of voluntary disclosure: quality and quantity. It takes advantage of the German setting, where forward-looking reporting has characteristics of both mandatory and voluntary disclosure: whereas forward-looking reports are legally mandated for public firms, no binding guidance exists regarding their structure, scope of items to be reported, time horizon, and precision of forecasts, assumptions, and other relevant parameters. We show evidence consistent with firms responding to extreme uncertainty by reducing disclosure quality but maintaining high levels of volume narrated.