The Impact of Corporate Governance on Informative Earnings Management in the Chinese Market

Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between corporate governance and informative earnings management (IEM) for Chinese listed firms. While most previous studies on earnings management adopt the opportunistic perspective, we examine earnings management from the informative perspective, treating discretionary accruals as a means for managers to signal private information to external stakeholders regarding the firm's future cash flows or potential earnings. We hypothesize that good corporate governance practices motivate firm managers to engage in informative earnings management. By developing a measurable proxy of IEM, we test the association of managerial IEM with internal corporate governance mechanisms. The empirical results support our hypotheses, indicating that corporate governance has a positive impact on the possibility of managerial IEM, and better corporate governance should contribute to improving the transparency of financial reporting and the informativeness of reported earnings.

This study investigates the association between a firm's corporate governance practices and managerial informative earnings management (IEM) in the Chinese context. The primary objectives of corporate governance are to monitor the behaviours of different interested parties and to reduce the agency costs underlying various principal–agent relations (Karpoff et al., 1996; Lemmon and Lins, 2003). In particular, corporate governance facilitates a firm's stakeholders to monitor managers’ behaviours and business operations, to safeguard shareholders’ investment, to reduce information asymmetry between managers and other stakeholders, and to ensure the reliability and informativeness of managerial performance reports (e.g., the financial statements) (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; Denis and McConnell, 2003; Wilkinson and Clements, 2006; Kanagaretnam et al., 2007; Huson et al., 2012). However, managers often engage in earnings management when preparing and presenting financial statements to fulfil specific purposes.

There are two perspectives in earnings management. The opportunistic perspective holds that managers seek to mislead investors through manipulating periodic earnings so as to maximize their own utilities (Burgstahler and Dichev, 1997; Healy and Wahlen, 1999). On the contrary, the information perspective holds that managerial discretion is a means for managers to communicate their own expectations about the firm's future cash flows or profitability (Holthausen and Leftwich, 1983; Guay et al., 1996; Burgstahler et al., 2004). Most previous studies have predicated and drawn their conclusions on the opportunistic perspective for earnings management and have not tested the information perspective (Burgstahler and Dichev, 1997; McNichols, 2000; Baber et al., 2006; Curtis et al., 2011; Jansen et al., 2012). Ronen and Yaari (2008) point out that research is rare on factors that affect the motivations and consequences of the different types of earnings management.

In this study, we identify cases of IEM and examine whether managerial IEM is associated with corporate governance. We test whether firms with good corporate governance are more likely to signal inside information to outside stakeholders through IEM in China. The reasons for this study in the Chinese context are multifold. First, there are few alternative sources of information regarding firm performance (especially the prospect of earnings performance) to the market in China. Unlike in the US and other developed markets, financial analysts from market intermediaries in China (e.g., investment banks, securities firms, and rating agencies) are not as systematic or reliable an information channel compared to their counterparts in developed countries. Although Chinese firms may make management forecast disclosures, which is currently non-mandatory, such a practice would impose additional legal liabilities on the firm and consume additional firm resources (Liang, 2005; Chen et al., 2008). Thus, the motivation for IEM to convey inside information is more substantial in China than in other developed markets where the availability of alternative information sources mitigates managerial incentives for IEM.

Second, there are some unique corporate governance mechanisms in China, such as the split-share structure with tradable and nontradable shares, 1 high ownership concentration with strong government control, the two-board governance structure with the board of directors (BOD) and the supervisory board (SB), cross-listing in domestic and overseas markets under varied market regulations, the introduction of mandatory corporate governance codes in 2002/2003, and the weak investor protection environment. As a result, the actual function of corporate governance in the Chinese market may substantially differ from that in Western countries (Firth et al., 2007, 2012). It is therefore interesting to examine the impact of the governance mechanisms with Chinese characteristics on the quality and informativeness of accounting information (earnings).

Third, all Chinese-listed firms have the same fiscal year-end (i.e., calendar year) and the same fiscal quarter ends consistently, which is not the case in the US and other markets where firms adopt varied fiscal years for financial reporting. As we need to obtain firms’ abnormal accruals for each quarter, it is important to preclude the potential seasonality noise of reporting period end in running the Jones model (i.e., quarterly and yearly performance may be distorted for firms in the same industry with similar operational cycling when they choose varied fiscal period ends). This requirement makes China a practical setting for our study.

Fourth, there are some unique settings in the Chinese stock market that may have a specific impact on earnings management conducted by the listed firms. For instance, the Chinese market regulatory authorities (e.g., China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) and the stock exchanges) have set specific earnings requirements (thresholds) for Chinese firms to pursue initial public offerings (IPOs) or seasonal equity offerings. On the basis of the fulfillment or consequential deviation from the required earnings targets, the listed firms may be subject to special trading restrictions or resumption of normal trading (i.e., special treatment—(ST)) and whether or not to be suspended from trading (or delisting) in the market (i.e., particular transfer—(PT)). 2 Obviously, Chinese firms’ motivation for earnings management (both opportunistic and informative) under such a regulatory environment is different from most other markets, which is worthy of particular empirical analysis.

Fifth, the Chinese government has promoted international accounting convergence and market regulation reforms toward international conventions in recent years. Thus, a study in the Chinese context may generate interesting evidence on the particular incentives and consequences of managers’ IEM and the impact of corporate governance on such managerial behaviour with broad implications.

There are both internal and external governance mechanisms to help bring the interests of managers in line with that of shareholders (Walsh and Seward, 1990). We focus on three specific aspects of Chinese firms’ internal corporate governance mechanisms as measured by: (1) the equity ownership structure (e.g., ownership concentration, blockholding, split-share system with large portion of nontradable shares, and cross-listing status); (2) the characteristics of oversight/monitoring establishments (e.g., the independence of the BOD and the SB); and (3) the activeness (effectiveness) of monitoring functions (e.g., by the BOD and the SB, and shareholder activism). We hypothesize that those internal governance devices or arrangements that promote good corporate governance should induce managers to pursue IEM and vice versa.

This study is motivated by three factors. First, an important function of financial reporting is to provide shareholders with a means of evaluating and monitoring managerial activities and business operations, and good corporate governance reduces information asymmetry between managers and external stakeholders and contributes to more comprehensive and reliable information disclosures while informative earnings can positively affect the usefulness of accounting information (Healy and Palepu, 2001; Fan and Wong, 2002; Bedard and Johnstone, 2004; Cornett et al., 2009; Jansen et al., 2012). A study of managerial IEM with respect to the function of internal governance mechanisms should expand our knowledge of the impact of corporate governance on managerial disclosures and information quality, especially the communication of managers’ private information to external stakeholders. Second, as pointed out by Dechow and Skinner (2000), because managerial discretions are unobservable from the financial statements, most definitions of earnings management have rested on the opportunistic perspective. As a result, the majority of previous research was concluded on the basis of the opportunistic perspective rather than on the informative perspective (Dechow et al., 1995; Holthausen et al., 1995; Teoh et al., 1998; Baber et al., 2006; Lento and Cotter, 2011), which is an incomplete picture in regard to managerial motivations and behaviours for earnings management. Third, although it is recognized in the literature that earnings management can be informative or ‘signalling’ instead of opportunistic in nature, this role has long been understated or neglected because of the difficulty in classifying IEM ex ante. This study intends to develop a practical approach to identifying IEM in the context of the relationship between quarterly managerial discretionary accruals and yearly earnings reported to facilitate further studies on the varied managerial motivations and consequences of earnings management and their impact on the quality of financial reports and informativeness of earnings. Overall, this study aims to contribute to the earnings management literature by analyzing the association of corporate governance with IEM in an effort to fill the gap in the extant literature.

An essential issue in this study is to identify IEM from opportunistic earnings management (OEM), for which there is no explicit benchmark/model to differentiate it in the literature. We use quarterly financial data to run the Jones (1991) model and modified Jones model (Dechow, 1994; Kothari et al., 2005) and estimate discretionary accruals in the quarterly reports disclosed by the Chinese listed firms to identify IEM. 3 When yearly firm performance (e.g., annual earnings) is expected to be lower (higher) than the previous year, managers’ private prediction of current annual earnings can be signalled out through negative (positive) quarterly discretionary accruals in the case of IEM. 4 Assuming that managers have inside information that enables them to predict that the current year's performance is worse than that of last year, if managers would like to convey this bad performance to external stakeholders, they can choose to lower the quarterly earnings (using negative discretionary accruals) so that external stakeholders will not hold an unreasonably optimistic view. On the other hand, managers would use positive discretionary accruals to send out the IEM signal in their quarterly reports if they expect a better yearly performance to come.

Subramanyam (1996) finds that discretionary accruals are useful in predicting future operating cash flows, and accounting earnings are basically more useful than current cash flows in predicting future cash flows and profitability. According to FASB/IASB (2010), an important objective of financial reporting is to provide useful information that will assist financial statement users (e.g., investors, creditors, regulators, etc.) in predicting a firm's future cash flows. We therefore argue that it is reasonable to view the quarterly earnings information as informative if it can help investors predict a firm's annual accounting performance. We thus define the IEM, which is original and simultaneously intuitively understandable. Because there is rare research on the measurement of IEM and whether corporate governance has an impact on IEM, our study should have profound theoretical and practical implications.

We further identify IEM with three different measures in terms of increasing rigorousness in specification. We then apply regression analyses of the relationship between the proxies for IEM and corporate governance mechanisms. Our regression results show that, in general, firms with weak corporate governance are less likely to conduct IEM. The findings indicate that although firms’ managers have incentives to engage in IEM, such managerial behaviour is positively related to the quality of corporate governance.

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we examine earnings management from the informative or signalling perspective. Most previous studies on earnings management have focused on the opportunistic perspective and conclude that earnings management has a negative impact on the quality of financial reporting. In particular, some recent China-related studies (Xie et al., 2003; Firth et al., 2007; Gulzar and Wang, 2011) report that earnings management dampens the informativeness of earnings in the Chinese market, and corporate governance mechanisms should be improved to reduce earnings management and to enhance the informativeness of earnings information. The underlying assumption in these studies is that earnings management is detrimental to earnings informativeness, and it should be curbed or eliminated (optimally be reduced to zero) for the sake of improving financial reporting quality and earnings informativeness. The assumption is, however, superficial because earnings management could contribute positively to earnings informativeness by conveying managerial private information to external investors and the market, or IEM is beneficial and should be encouraged instead of constrained or eliminated to enhance the informativeness of earnings information. Thus, our findings on IEM could go beyond the conclusions of mainstream studies and provide a new insight into the role of earnings management in quality financial reporting and the information relevance of earnings to users’ decision making.

Second, we develop a measurable proxy for IEM by comparing the correlation between the managerial discretionary accruals in quarterly reports and the yearly earnings in annual financial statements. Such a proxy is not only theoretically appealing but also measurable in testing. 5 Although the view of IEM has been recognized in the literature, the empirical analysis of its effect is rare because of a lack of appropriate measurement to differentiate IEM and OEM or because of the difficulty in attributing discretionary accruals to opportunistic or informative prospective ex ante. As a result, most previous research on earnings management ends up with the opportunistic perspective and reveals its negative impact on investors’ decisions (Healy and Wahlen, 1999; Dechow and Skinner, 2000; Ronen and Yaari, 2008; Cohen et al., 2011). However, we find that some managers in our sample firms have in fact conducted IEM through their use of quarterly discretionary accruals. Our IEM proxy should facilitate the study of informative earnings management and enrich the related literature.

Third, our study findings reveal that managers have a motivation to pursue IEM, or they will apply discretionary accruals in quarterly reporting and convey their private information about the firm's future cash flows and earnings potential to the market. Unlike OEM, IEM has a positive impact on the usefulness or predictability of earnings information and can enhance the relevance of financial statements to investors’ decision making. This finding should shed a new light on the motivations and consequences of earnings management, supplementing the prevailing views derived from an opportunistic perspective on earnings management. In particular, previous studies have documented a rampant earnings management phenomenon in the Chinese market because of specific institutional or regulatory requirements (Chen and Yuan, 2004; Firth et al., 2007). However, those studies are mainly based on the opportunistic perspective of earnings management, that is, they assume that managers use judgement in financial reporting or structure transactions to misrepresent the underlying economic performance or to influence contractual outcomes that depend on reported accounting numbers. We do not deny that Chinese firms, compared with their counterparts in most developed markets, have even stronger motivations or incentives to engage in earnings management for opportunistic purposes (such as competition for IPO quotas, seasonal rights offers, maintaining listing status or avoiding special trading treatments or delisting, tunnelling to parent companies through related-party transactions, etc.), but we do find that some Chinese listed firms (27%–47% of our observations in terms of the varied specifications of IEM) have used quarterly discretionary accruals for IEM, which is a significant earnings management motivation, and the consequence cannot simply be ignored. As there is a lack of reliable alternative information about prospective firm performance to the market in China, managers of some Chinese firms have to rely on quarterly IEM to convey private information about future firm performance. Thus, our study findings can supplement other China studies to provide a more complete picture of the motivations and implications of earnings management in the Chinese context.

Fourth, there is a void in the extant literature about the relationship between corporate governance and IEM, although many studies contend that corporate governance can improve the quality and usefulness of accounting information disclosed by managers (Karamanou and Vafeas, 2005; Kalelkar and Nwaeze, 2011). This study is, to our knowledge, the first to directly examine the impact of corporate governance on firms’ IEM. Previous studies report that good corporate governance is associated with less earnings management (Klein, 2002; Xie et al., 2003; Gulzar and Wang, 2011) but fail to differentiate the possible existence of both opportunistic and informative earnings management. Also, Firth et al. (2007) investigate the association between some corporate governance mechanisms of Chinese-listed firms (e.g., ownership and board structure) and informativeness of earnings in terms of the earnings response coefficient and discretionary accruals, and conclude that ‘discretionary accruals are opportunistic then firms with a very dominant shareholder have lower accounting quality’ (p. 487). Although they suggest that good corporate governance can improve the trustworthiness of earnings information, their contention is confined to the traditional assumption of OEM that the use of discretionary accruals is opportunistic or negative to the informativeness of earnings. However, we posit and find evidence that good corporate governance practices actually motivate or facilitate managers to engage in IEM by communicating inside information about the earnings prospect, which can assist external investors in assessing the amount and timing of future cash flows and enhance the effectiveness of their evaluation of management performance and related decisions. Our findings extend beyond the extant studies and demonstrate that good corporate governance can facilitate managerial IEM and enhance the predictability of accounting information, which further testifies to the value of corporate governance. The positive relation between corporate governance and IEM revealed by this study should have important policy implications for market regulators, standard setters, and investors.

This is a study in the Chinese context in respect of the association between corporate governance and IEM, but the underlying principles and research design could have general applicability. Although the Chinese stock market regulation has some unique characteristics, managerial motivations or behaviours for IEM should also exist in other markets, which has been recognized or hypothesized in the literature. Thus, our study based on Chinese evidence should not only help readers understand the development of financial reporting and corporate governance in the largest emerging capital market in the world but also facilitate other researchers to carry out studies of IEM under different market settings.

Literature Review

Accrual Accounting and Informativeness of Earnings

The primary role of financial reporting is to adequately portray a firm's financial position and performance in a timely and credible manner. Financial reports are thus prepared to convey managerial information about the firm's performance. Because of the separation of ownership and management, managers possess some inside information about the firm's economic fundamentals, which may have a crucial impact on users’ decision making. Under the current financial reporting framework, accounting standards permit managers to exercise judgement in financial reporting. Managers can then use their knowledge of the business and its opportunities to select reporting methods and estimates that match the firm's economic fundamentals, potentially increasing the usefulness of accounting information because earnings is informative from the perspective of external investors’ decision making (Krishnan, 2003; Siregar and Utama, 2008). However, managerial judgement also creates the possibility for earnings management, through which managers may fulfil their specific reporting purposes (Cohen et al., 2011).

Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) provide managers with considerable discretion in their choice of accounting procedures (Watts and Zimmerman, 1990). There are many ways that managers can exercise judgement to influence financial reports. For example, judgement is required to estimate numerous future economic events that are reflected in financial statements, such as expected lives and salvage values of long-term assets, obligations for pension benefits and other postemployment benefits, deferred taxes, and losses from bad debts and asset impairment. Managers can also choose among acceptable accounting methods for the same economic transactions (such as different depreciation and inventory valuation methods). In addition, managers may apply accounting accruals (discretionary accruals in particular) to adjust the periodic earnings to be reported. Thus, earnings management is a common phenomenon in financial reporting (Verrechia, 1986; Dechow et al., 1995; McNichols, 2000; Bartov and Mohanram, 2004; Baber et al., 2006).

Accrual-based financial reporting ‘provide(s) information to help present and potential investors, creditors and others assess the amounts, timing, and uncertainty of prospective net cash inflows to the related enterprise’. Thus, ‘accrual accounting uses accrual, deferral and allocation procedures whose goal is to relate revenues, expenses, gains and losses to periods to reflect an entity's performance during a period instead of merely listing its cash receipts and outlays’ (FASB/IASB, 2010). Accounting accruals mitigate the timing or mismatching problems of current cash flows (Dechow, 1994). Accruals have been found to be positively and incrementally priced by the stock market after controlling for cash flows (Subramanyam, 1996). Many studies demonstrate that accruals contain significant incremental information about future cash flows and lead to earnings that are superior to current cash flows in predicting future cash flows (Bernard and Stober, 1989; Finger, 1994; Lore and Dillinger, 1996; Balsam, 1998; Barth et al., 2001; Kothari et al., 2005; Kalelkar and Nwaeze, 2011). Tucker and Zarowin (2006) report that by using discretionary accruals to smooth periodic income, the association between current-year stock returns and future earnings (namely, the earnings response coefficient) is strengthened. 6

In fact, discretionary accruals enable managers to communicate private information that is useful to external stakeholders (Dechow, 1994; Dechow and Dichev, 2002; Huson et al., 2012), decrease noise in the underlying cash flows, and increase the informativeness of earnings (Balsam et al., 2002). This can arise if certain accounting choices or estimates are perceived to be credible signals of a firm's financial performance (Cohen et al., 2011). Krishnan (2003) shows that accrual accounting allows managers to communicate inside information to stakeholders, which improves the ability of earnings to reflect a firm's underlying economics. Siregar and Utama (2008) also demonstrate that there is an association between discretionary accruals and future profitability. In addition, Cahan et al. (2008) reveal that the association between earnings informativeness and income smoothing is higher in countries with stronger investor protection. 7

Opportunistic and Informative Perspectives of Earnings Management

However, accruals can be used opportunistically, distorting the information provided by managers, introducing noise into earnings, and lowering the informativeness of reported earnings (Bernard and Skinner, 1996; Gonchrov, 2005). Self-interested managers may report earnings by selectively defining and measuring different accruals (e.g., discretionary accruals) to meet certain performance benchmarks to maximize their own utilities even at the expense of outside investors. Managerial motivations for OEM include external contract incentives such as debt contracts, dividend covenants, and regulatory contracts (Holthausen and Leftwich, 1983; Healy and Palepu, 1990; DeFond and Jiambalvo, 1994; Sweeney, 1994) and management compensation contracts (e.g., Healy, 1985; DeAngelo, 1988; Dechow and Sloan, 1991; Holthausen et al., 1995; Guidry et al., 1999; Bartov and Mohanram, 2004). OEM produces manipulated earnings that mislead external stakeholders about the underlying economic performance of the firm. This may happen as managers have access to information that is not available to external stakeholders. Many studies confirm that OEM has a negative impact on the quality of financial reporting and reduces the credibility and usefulness of earnings information in investors’ decisions (Dechow et al., 1996; Teoh et al., 1998; Healy and Wahlen, 1999; Baber et al., 2006; Firth et al., 2007; Kalelkar and Nwaeze, 2011).

Although discretionary accruals are normally viewed as an indication of OEM, they could be used to signal inside information as well. For example, Subramanyam (1996) finds evidence that income smoothing can improve the persistence and predictability of earnings and that discretionary accruals can convey the firm's future profitability. His empirical results are inconsistent with the pervasive perspective of OEM in which accrual manipulations distort earnings information. Jiraporn et al. (2008) also support the informative earnings management perspective and acknowledge that earnings management may be beneficial because it potentially venhances the information content of earnings. They contend that if earnings management is to be used opportunistically, firms where agency costs are severe should exhibit a higher degree of earnings management. On the other hand, if earnings management is to be used as a way to communicate inside information to external shareholders and the public, firms with severe agency costs should not exhibit a high degree of earnings management. Their empirical evidence supports an inverse relationship between agency costs and earnings management, which indicates that earnings management, to a certain extent, may not be opportunistic but informative, and a similar finding is reported by Siregar and Utama (2008). Lento and Cotter (2011) empirically find that investors reward (discount) a firm's value in respect of the MBE premium when the market is confident that earnings management by the firm is informative (opportunistic).

In addition, managers can overcome the limitations of current accounting standards and use accounting judgement to improve corporate transparency and to make financial reports more informative to users. More firm-specific information can be made available to the public through managers’ use of judgements and accruals (Chaney et al., 2011). Therefore, as initially pointed out by Holthausen and Leftwich (1983), earnings management can also be conducted to increase the information content of financial statements, also known as IEM. Managers may apply managerial discretion (e.g., discretionary accruals) to reveal their private expectations about the firm's economic fundamentals or future cash flows (Demski, 1998; Guay et al., 1996). Because managers are closely involved in investing and operating decisions, they are in a better position to estimate the firm's future prospects such as future cash flows and earnings. Managers are willing to convey this inside information to external investors by IEM if they believe such information will not only increase firm value and investors’ benefits but also maximize their own utilities (Evans and Sridhar, 1996; Demski, 1998; Jo et al., 2007).

Therefore, there is a sharp difference in the motivations and economic consequences of IEM and OEM, although many researchers have simply defined earnings management only from the opportunistic perspective (Healy and Wahlen, 1999; Barth et al., 2001; Bedard and Johnstone, 2004; Cornett et al., 2009; Jansen et al., 2012). Burgstahler and Dichev (1997) argue that OEM is used to ‘mask’ or ‘obscure’ true economic performance by withholding information about current or future (potential) performance, whereas IEM helps better predict the amount and timing of current or future cash flows or earnings. Thus, it is in fact beneficial to external financial statement users and can improve the relevance or usefulness of earnings information to investors’ decisions (Lee et al., 2006; Siregar and Utama, 2008). However, there is a general lack of empirical evidence on IEM because of the difficulty in specifying discretionary accruals as opportunistic and informative, ex ante, which results in a majority of studies on earnings management ending up with an opportunistic perspective, although IEM is another distinct motivation and consequence of earnings management. IEM is definitively an important topic worthy of empirical study. Because the opportunistic view regards earnings management as detrimental to accounting information usefulness, many researchers assume that earnings management should be avoided or eliminated for the sake of quality financial reporting. However, a complete elimination of earnings management, if that is indeed possible, does not warrant the informativeness of accounting numbers because IEM should convey management's private information about the firm's prospective earnings that can enable external investors to have a more accurate assessment of the firm's future cash flows and profitability. In other words, IEM is not harmful but beneficial to the relevance and usefulness of accounting information, and it should be promoted instead of being avoided. Therefore, research on earnings management, by distinguishing IEM from OEM, will have profound theoretical and practical implications.

Information Asymmetry, Corporate Governance, and Accounting Information Quality

Finance theory suggests that the demand for financial reporting and disclosure arises from agency conflicts and information asymmetry between firm managers and outside investors (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Under separation of ownership and management, managers may not act in the best interests of shareholders. Thus, corporate governance is established to reconcile the potential conflict of interest among related parties to a firm, and especially to ensure the effective execution of various contracts between shareholders (principals) and firm management (agents). Financial reporting serves to reduce information asymmetry and agency costs or contracting costs. The reliability and completeness of information disclosure is critical to firm values and to investors’ decision making (Healy and Palepu, 2001).

Corporate governance is a key element of a modern incorporation system and consists of a series of internal and external regulations, rules, managerial control and monitoring devices, and related procedural arrangements for a company to check and balance the varied interests of its stakeholders (Karpoff et al., 1996; Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; Beasley et al., 2000; Lemmon and Lins, 2003). Under a sound corporate governance system, managers will follow the guidance of the BOD and effectively use the entrusted resources to carry out operating activities to create firm value and maximize the interests of all stakeholders (Denis and McConnell, 2003; Lemmon and Lins, 2003). Thus, good governance arrangements will reduce the agency costs resulting from agency conflicts between shareholders and managers, shareholders and creditors, large shareholders and minority shareholders, and so on. The adequate function of corporate governance is a premise for a business firm to operate efficiently and effectively (Jiraporn et al., 2005; Wilkinson and Clements, 2006; Ettredge et al., 2011). In addition, corporate governance has a direct impact on financial reporting quality. With effective supervision or monitoring of managerial behaviours and reporting activities, firms’ internal control systems can function effectively and ensure managers provide complete and reliable information for contract execution (Kanagaretnam et al., 2007; Cornett et al., 2009; Kalelkar and Nwaeze, 2011; Huson et al., 2012).

Although there are incentives and possibilities for managers to conduct OEM to act in their own self-interest, good corporate governance will not only curtail managerial opportunistic reporting but will also encourage managers to engage in IEM to convey their private information about the firm's long-term performance. As a result, corporate governance can help increase the informativeness of financial reporting and reduce information asymmetry to mitigate agency conflicts and maximize firm value (Bedard and Johnstone, 2004; Bushman et al., 2004; Chung et al., 2010; Jansen et al., 2012). Owing to the positive role of corporate governance in ensuring quality financial reporting, it can therefore be posited that there is a positive association between corporate governance quality and managerial IEM.

Many empirical studies confirm that corporate governance is positively associated with the quality of financial reports from different governance perspectives. In particular, Klein (2002) finds that a firm's discretionary accruals (a proxy for OEM) is negatively related to the independence of BOD, and the level of discretionary accruals declines as the BOD becomes more independent. Xie et al. (2003) report similar findings. Beasley et al. (2000) find that there is a negative association between corporate governance and the possibility of fraud in financial reporting as fraudulent companies have, in general, weaker corporate governance structures. DeZoort and Salterio (2001) reveal that the independence and expertise of audit committees under the BOD can significantly improve financial reporting quality. Dunn and Mayhew (2004) report that financial statement fraud is more likely to occur in firms with higher insider ownership power (an internal governance arrangement). Some other studies also document that good corporate governance practices contribute to corporate transparency and can significantly lower the possibility of nonstandard auditor opinions issued by external auditors in their audit engagements (Bedard and Johnstone, 2004), reducing the number of financial statement restatements (Abbott et al., 2007) or the likelihood of disciplinary sanctions by market regulators (Ettredge et al., 2011). Firth et al. (2007) report that Chinese firms with highly concentrated ownership have lower earnings informativeness, but the SB system does play an important role in improving the informativeness of earnings (i.e., better earnings–returns association, smaller magnitude of discretionary accruals, and fewer modified auditor opinions). These studies all suggest that sound corporate government mechanisms can effectively mitigate the potential conflicts between managers and shareholders, thus reducing agency costs and information asymmetry accordingly.

Because managers have strong motivations and the possibility of using discretionary accruals for earnings management, their behaviours affect the credibility of earnings information reported. Therefore, the quality of corporate governance will impact managerial incentives and the capability for earnings management. With sound corporate governance in place, all internal and external oversight and monitoring mechanisms and procedures function effectively, which can prevent or deter managers from expropriation behaviour and opportunistic financial reporting, and reduce managerial incentives for, and the possibility of, OEM, thus enhancing financial reporting quality or ensuring the reliability of accounting information (earnings information in particular) and its relevance to firm valuation and investors’ decisions. Karamanou and Vafeas (2005) report that in firms with an effective corporate governance arrangement, the magnitude of discretionary accruals is reduced, as is the noise in reported earnings. As a result, earnings information should have better predictive value. Morck et al. (2005) also support this proposition.

A firm's corporate governance system includes both internal mechanisms (i.e., ownership structure, composition of the BOD and director qualifications, internal oversight or monitoring devices, internal control and audit procedures, managerial shareholding, executive compensation contracts and incentives packages, etc.) and external mechanisms (governmental or market regulation, debt covenants, labour markets for managers, independent external audits, etc.). Because managers’ earnings management activities through the use of discretionary accruals are normally unobservable by external stakeholders, this study focuses mainly on the effect of internal corporate governance mechanisms on managerial IEM. We posit that the existence and actual function of internal governance mechanisms will affect not only the standard of corporate governance but also the content and quality of financial information disclosed by managers. Nonetheless, whether and how these corporate governance mechanisms will impact managerial motivations and IEM behaviours remains an empirical issue.

Hypotheses Development

Financial statements are a crucial part of the information pipeline that facilitates the execution of various contracts and internal monitoring and control. Sound corporate governance practices reduce information asymmetry by prompting managers to provide investors and outsiders with reliable and complete information, thereby increasing corporate transparency and reducing monitoring costs in contract execution. Thus, the quality of information available to investors is influenced by the way a firm is governed (Healy and Palepu, 2001). We posit that corporate governance should induce or constrain managers’ motivations and behaviours regarding earnings management. In light of the positive impact of corporate governance on reducing information asymmetry and enhancing financial reporting quality, we establish our overall proposition as follows:

Proposition.Corporate governance quality has a positive impact on managerial motivation to engage in informative earnings management in the Chinese market.

Because a firm's internal corporate governance mechanisms consist of various oversight or monitoring arrangements or devices (Denis and McConnell, 2003), we further specify the overall proposition with three hypotheses in respect of three major characteristics of corporate governance under the existing regulatory environment in China: (1) the equity capital structure arrangement (i.e., ownership concentration, dominance of nontradable shares, blockholding, and cross-listing status) 8; (2) the independence of the oversight/monitoring establishments (i.e., the duality of BOD chairman and CEO positions, the proportion of independent directors, and the SB size); and (3) the activeness (effectiveness) of oversight/monitoring by the BOD, the SB, and the shareholders. We offer the following hypothesis in respect of equity structure arrangement:

H1.Sound equity capital structure positively affects managerial incentives or the possibility of informative earnings management.

In countries with a relatively weak corporate governance environment such as China, ownership concentration is frequently used to moderate the lack of investor protection. Concentrated ownership structure leads to two obvious consequences for corporate governance, as surveyed in Morck et al. (2005). On one hand, dominant shareholders have both the incentive and the power to discipline management. On the other hand, because the interests of controlling and minority shareholders are not fully aligned, concentrated ownership will increase the entrenchment of large shareholders and create a new (Type II) agency problem (La Porta et al., 1999; Mayhew et al., 2003). In China, firm ownership is highly concentrated to state agents, and the legal protection of minority shareholders is insufficient (Firth et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2010); thus, ownership concentration may lead to severe entrenchment problems and information opacity.

A Chinese listed firm usually has a large controlling shareholder, often the government or a parent state-owned enterprise (SOE). Johnson et al. (2000) argue that more narrowly held firms may face greater agency conflicts because the controlling shareholders have a dominant influence on corporate affairs and they can easily bypass monitoring by other shareholders. In China, controlling shareholders frequently engage in benefit transfers through the misappropriation of funds and party-related transactions to expropriate the interests of minority shareholders (Lin et al., 2007). Therefore, listed firms with high ownership concentration are more likely to engage in OEM for the sake of exploiting minority shareholders (Firth et al., 2007), so they are less likely to convey inside information to the public. In other words, ceteris paribus, the more shares held by the largest shareholder, the less likely there will be managerial IEM. Therefore, we further specify the first sub-hypothesis as follows:

H1(a).Ownership concentration is negatively associated with the likelihood of managerial informative earnings management.

The finance literature contends that equity blockholders and institutional investors tend to promote shareholder-driven corporate strategies, thus increasing monitoring over large shareholders and managers and improving corporate governance. Several empirical studies have concluded that both large equity blockholders and institutional investors can improve firm performance, suggesting that there is a positive association between large noncontrolling shareholders and firm value (Holderness and Sheehan, 1985; Mikkelson and Ruback, 1985; Lemmon and Lins, 2003). This is because the large noncontrolling shareholders (blockholders) are, out of self-interest, willing and able to monitor the controlling shareholder, preventing him or her from taking too much (Pagano and Roel, 1998; La Porta et al., 1999; Claessens et al., 2002). This is particularly true for Chinese listed firms, as equity blockholders—other than the largest shareholder (e.g., a government agency or parent SOE)—hold relatively fewer shares with a vulnerable position and have a great incentive to stay alert regarding potential exploitation by the largest shareholder (Wei et al., 2005). We expect that, ceteris paribus, more shares held by blockholders (e.g., the second to the fifth largest shareholders) can improve corporate governance and can prompt firm managers to pursue IEM:

H1(b).Shares held by blockholders have a positive impact on managerial informative earnings management.

Before China's split-share structure reform (‘circulation of all shares’) in 2005, domestic A-shares were divided into nontradable and tradable shares. Nontradable shares represent the interests of governments and related parent entities and have a dominant influence on a firm's operating decisions, whereas holders of tradable shares can exercise little influence on the decisions made by the nontradable shareholders and management. This is a typical structure with severe agency conflicts (Ding et al., 2010). The split-share structure reform introduced by the government in 2005 requires that nontradable shareholders have to bargain with tradable shareholders to gain liquidity. 9 Kwan (2006) explains that the main aim of the reform is to improve corporate governance in listed firms and to enhance the intermediary function of the stock market by giving equal rights to tradable and nontradable shareholders. Firth et al. (2007) find that Chinese firms publish higher quality accounting information when they have more tradable shares. Therefore, we argue that, with tradable shares, information asymmetry decreases while earnings informativeness increases, and, ceteris paribus, a firm with a higher percentage of nontradable shares will have poor corporate governance and information disclosure environment and is less likely to engage in IEM:

H1(c).Nontradable shares discourage firm managers from informative earnings management.

Some Chinese companies choose to list their shares simultaneously in the domestic market and overseas stock exchanges such as Hong Kong, London, New York, and Singapore. The most frequently cited reasons or benefits for a firm to cross-list in foreign markets are improved access to capital, greater liquidity, lower capital costs, heightened corporate prestige, and better investor protection (Karolyi, 1998). Bushman et al. (2004) document that financial transparency is higher in countries with higher levels of judicial efficiency and a common law background, or in countries where stock markets are more developed and better regulated. Thus, cross-listing in different stock markets, especially in the more developed capital markets, will expose listed firms to more stringent or transparent listing rules and disclosure requirements, which should improve the firm's corporate governance and information quality (Karolyi, 1998; Lang et al., 2003b). Cabán–García (2009) compares the quality of the reported earnings of cross-listed European firms with that of a control group of non-cross-listed domestic firms and finds that the variance in earnings quality is positively associated with the difference in the strictness of regulatory/disclosure requirements between foreign and domestic exchanges. Therefore, cross-listing can also act as an ownership structure device to carry out governance monitoring over accounting and reporting for the Chinese listed firms. We posit that, ceteris paribus, a firm with a higher percentage of shares cross-listed in overseas stock exchanges is more likely to engage in IEM.

H1(d).Cross-listing status can facilitate managerial informative earnings management.

We present our second hypothesis in light of the independence of monitoring/oversight governance establishment:

H2.The independence of a firm's oversight or monitoring setups will positively affect managerial motivation and behaviour for informative earnings management.

The BOD is a vital device for overseeing management and business operations as it is responsible for appointing, removing, and remunerating senior managers to ensure that managers act in the best interests of the shareholders. The independence of the BOD assures its effective oversight (Denis and McConnell, 2003). However, there is increasing criticism that the BOD's oversight function is weakened if a BOD chairman is the same person as the CEO (Shivdasani and Yermack, 1999) because this practice results in low transparency of the CEO's activities, and his or her actions can go unmonitored, which paves the way for scandals and corruption. 10 On the other hand, the separation of the two positions allows the BOD chairman, on behalf of stockholders, to be more impartial in overseeing the CEO's work and overall management performance (La Porta et al., 2002; Yeh and Woidtke, 2005). Splitting the two positions should therefore enhance the independence of the BOD and its oversight function, which will not only improve corporate governance but also lead to better communication of inside information to the BOD and shareholders at large. Several studies have confirmed this proposition with convincing empirical evidence (Chang and Sun, 2009). Therefore, we hypothesize that separating the positions of BOD chairman and CEO enhances the chance for managerial IEM in China:

H2(a).The separation of board chairman and CEO positions has a positive impact on managerial informative earnings management.

Most stock markets require the appointment of independent directors as a means of strengthening the BOD function (Denis and McConnell, 2003; Gordon, 2007). Independent directors can deter CEO entrenchment and enhance the BOD's oversight regarding the CEO and other senior managers and their operating decisions. Independent directors can also be more readily mobilized by legal standards to help provide more accurate disclosures, enhancing the informativeness of the financial statements and improving compliance with laws (Sale, 2006). In addition, independent directors are less wedded to inside accounts of the firm's prospects but more sensitive to external assessments of their performance. Weisbach's (1988) widely cited study of CEO terminations in New York Stock Exhange listed firms over the 1974–1983 period concludes that ‘when boards are dominated by outside directors, CEO turnover is more sensitive to firm performance than it is in firms with insider-dominated boards’ (pp. 33–34). Uzun et al. (2004) show a negative relationship between business frauds and board independence. Firth et al. (2007) report that Chinese listed firms with more independent directors sitting on the BOD have greater earnings informativeness and are more likely to receive clean audit opinions. Thus, we propose that, ceteris paribus, a firm with a large proportion of independent directors in the BOD is more likely to engage in IEM.

H2(b).The proportion of independent directors on the board has a positive impact on managerial informative earnings management.

Chinese firms adopt a two-tier board structure, that is, the BOD and the SB under company law. The SB is composed of the shareholders’ representatives and an appropriate proportion of employee representatives who are nominated by the firm's employee union. The Standard Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies in China, issued by the CSRC and the State Economic and Trade Commission in 2002 further requires that the SB members should have some professional knowledge or work experience in the fields of law and accounting. As per company law, the SB has a clear monitoring mandate to carry out a series of responsibilities, including monitoring the performance of directors and senior managers for compliance with the laws and articles of incorporation, reviewing the financial affairs of the firm, and submitting an SB report to shareholders’ annual general meeting (Lin and Chen, 2005).

Under the two-tier board system, the BOD and the SB play a supplementary oversight role in regard to internal governance. Normally, expertise and monitoring capability increase with the size of the SB, that is, a large SB should have more members equipped with accounting and law knowledge and carry out a more effective SB monitoring function (Xiao et al., 2004; Firth et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2010). Lin and Liu (2009) empirically find that firms with smaller SBs are less likely to hire a Top 10 (high-quality) auditor in China, and their financial statements are of relatively low quality. Previous studies (Krishnan, 2003) indicate that lower quality auditors are less likely to deter and detect questionable accounting practices and irregularities in firms, which provides a greater chance for opportunistic reporting. We therefore posit that SB size has a bearing on governance monitoring and on managerial engagement in earnings management. Ceteris paribus, a firm with a large SB is more likely to engage in IEM:

H2(c).A large supervisory board can facilitate managerial informative earnings management.

Our last hypothesis on the association between corporate governance and IEM concerns the activeness (effectiveness) of the governance oversight or monitoring function:

H3.The active function of oversight/monitoring mechanisms is positively associated with managerial informative earnings management.

The effectiveness of internal governance mechanisms relies mainly on their actual implementation/operation. Previous research shows a negative relationship between the level of board activeness and the likelihood of a firm's opportunistic earnings restatements (O'Connor et al., 2006). Vafeas (1999) reports that the activity level of directors is positively associated with firm performance and suggests that the number of board meetings per year may indicate the activity level of the directors. It is generally recognized that high activity leads to better BOD oversight on accounting and reporting matters and may thus enhance the informativeness of earnings (Vafeas, 1999; Karamanou and Vafeas, 2005). Therefore, we posit that, ceteris paribus, a more active BOD increases the chance of managerial IEM. Similarly, Firth et al. (2007) report a direct relationship between the activeness of the SB and the informativeness of earnings data. Their empirical results indicate that a larger and more active SB can improve the earnings–returns association and financial reporting quality. Thus, we expect that an active SB is able to play an effective governance role and to improve the firm's information disclosure. Ceteris paribus, a more active SB more likely leads to managerial IEM:

H3(a).The effectiveness of the board and SB can positively contribute to managerial informative earnings management.

Along with increasing attention to corporate governance, the active role of shareholders in monitoring and controlling the BOD and the management is becoming more important (Choi and Cho, 2003). Shareholder activism has emerged as a significant factor in corporate governance. Proponents of shareholder activism argue that firms with active and engaged shareholders are more likely to succeed in the long term (La Porta et al., 2002). Vigilant shareholders act as the arbitrators in internal governance matters. Shareholders with significant ownership positions have both the incentive to monitor the executives and the influence to bring about changes they feel are beneficial (Holderness and Sheehan, 1985; Claessens et al., 2002). The active participation of shareholders in the annual general meeting will put great pressure on the BOD and the managers, which can strengthen internal governance, reduce information asymmetry, and improve financial reporting quality. For this study, we use the registered shares attending annual general meetings over total shares issued to measure shareholder activism and assume that, ceteris paribus, a firm with more active shareholders is more likely to engage in IEM:

H3(b).Shareholder activism is positively associated with managerial informative earnings management.

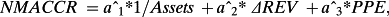

Research Methodology

To identify IEM, we firstly use quarterly data for the first three quarters in a year to run the Jones model and to estimate discretionary accruals for the quarterly reports of all sample firms. By definition, managers should use negative (positive) quarterly discretionary accruals to signal poorer (better) yearly performance compared with the previous year in regard to the perspective of IEM. For example, if managers predict that the current year's earnings performance is worse than the previous year's and would like to signal a bad yearly performance to external investors, they would choose to lower the quarterly earnings (by using negative discretionary accruals) so that external investors will not expect a good year ahead. On the contrary, if managers predict better performance for the current year, they should signal to the external investors by using positive discretionary accruals in quarterly reporting. As shown in Figure 1, there are four possible combinations for yearly earnings (YE) and quarterly discretionary accruals (QDA). In the shaded areas, QDA(+) and QDA(−) are useful for investors to predict YE changes (i.e., YE(+) and YE(−)) before the end of the fiscal year, and these cases are identified as IEM. 11 However, in the areas with white background, QDA is more likely to lead investors to predict a wrong sign (inconsistent changing direction) of YE changes and hence is identified as non-IEM.

Variables are defined in Table 1. In order to control for the mechanical relationships between discretionary accruals and earnings that might interfere with the identification of managerial behaviour (opportunistic vs. informative), we apply three specifications to identify IEM. As indicated, IEM1 is defined as the use of discretionary accruals in quarterly reporting to foretell yearly earnings (consistency in the sign of QDA and YE). IEM2 has an additional condition, as the magnitude of quarterly discretionary accruals is larger than that in yearly discretionary accruals to mitigate the potential managerial manipulation of quarterly accruals for OEM, which addresses the issue that discretionary accruals may not be truly ‘discretionary’, as pointed out in previous studies (e.g., Siregar and Utama, 2008). IEM3 is specified as the use of quarterly accruals to foretell net-of-discretionary-accruals yearly earnings to moderate the potential distortion effect of discretionary accruals in the yearly earnings per se. As quarterly discretionary accruals are included in the annual earnings and may lead to a mechanical relationship, IEM3 can help tackle such a concern. 12 For corporate governance variables, we assume that the equity capital structure of a listed firm, including ownership concentration (shares held by the largest owner (LSH) and by other blockholders, the second to the fifth largest shareholders (LSH2–5)), percentage of nontradable shares (NONTRA), and cross-listing shares (CROLIS), will have an impact on the strength of corporate governance monitoring, which will either dampen (e.g., LSH and NONTRA) or stimulate (e.g., LSH2–5 and CROSLIS) managerial motivations for IEM. For the characteristics of oversight or monitoring establishment, a higher proportion of independent directors (INDDIR) and a large SB (SUPER) will enhance the independence of oversight/monitoring establishment, whereas the duality of the CEO and the BOD chairman (CEOCHR) will hamper the BOD's oversight role. Nonetheless, the activeness (measured by the number of meetings held each year) of the BOD (BODMEET) and the SB (SBMEET) as well as shareholder activism (percentage of registered shares participating in annual general meetings (SAGM)) should strengthen the effectiveness of internal oversight/monitoring over management. Intuitively, variables that contribute to the effective function of corporate governance mechanisms should induce managers to pursue IEM, whereas those representing poor corporate governance should expand managerial incentives for opportunistic rather than informative earnings management. In summary, those governance mechanisms/arrangements that strengthen (weaken) corporate governance functions should positively (negatively) contribute to the IEM conducted by management.

| IEM1 | = 1 if a firm uses negative (positive) discretionary accruals in their quarterly earnings to foretell decrease (increase) of yearly earnings; 0 otherwise |

| IEM2 | = 1 if a firm uses negative (positive) discretionary accruals in their quarterly earnings to foretell decrease (increase) of yearly earnings and the magnitude of quarterly discretionary accruals is larger than that of yearly discretionary accruals; 0 otherwise |

| IEM3 | = 1 if a firm uses negative (positive) discretionary accruals in their quarterly earnings to foretell decrease (increase) of net-of-discretionary-accruals yearly earnings; 0 otherwise |

| LSH | = shareholding of the largest owner |

| LSH2_5 | = sum of shareholding of the second-, third-, fourth-, and fifth- largest owners |

| MSH | = the percentage of ordinary shares held by senior executives in the management team |

| NONTRD | = the ratio of non-tradable shares to total shares |

| CROLIS | = 1 if the firm is cross-listed on an overseas stock exchange; 0 otherwise |

| CEOCHR | = 1 if CEO and BOD chairman are the same person; 0 otherwise |

| INDDIR | = the ratio of independent directors to total directors |

|

SUPER BODMEET |

= natural logarithm of the number of supervisory board members = the number of meetings of the BOD in a year |

| SBMEET | = the number of meetings of the SB in a year |

| SAGM | = shares of annual general meeting, as a percentage of total shares outstanding |

| LNASSET | = natural logarithm of total assets |

| ROA | = profitability, equal to net income divided by total assets |

| LEV | = leverage, measured as total liabilities divided by total assets |

| SEO | = 1 if there is a SEO in the following year; 0 otherwise |

| ST/PT | = 1 if the listed firm has ST or PT status; 0 otherwise |

| BigN | = 1 if the listed firm is audited by a BigN auditor; 0 otherwise |

In addition, firm size (LNASSET), profitability (ROA), and leverage (LEV) are controlled, as some previous studies report that they are influential factors to the quality of corporate governance and financial reporting (Healy and Palepu, 2001; Huson et al., 2012). We also control for managerial shareholding (MSH), 13 seasonal equity offering (SEO), audit quality (BigN), and the listing status of special trading treatments (ST/PT), as these variables may directly influence management incentives or the capability for earnings management (Mayhew et al., 2003; Kanagaretnam et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008; Firth et al., 2012). Because earnings management may be affected by a change in real economic activity, we also include the regional gross domestic product (GDP) as a control (Cahan et al., 2008). In addition, industrial and yearly dummies are included in the regressions.

Empirical Results

Description of Data

Our sample covers all firms listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SHSE) and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) from 2004 to 2007 because of two considerations. 14 15 First, the Chinese stock market underwent major corporate governance reforms in the early 2000s, including the implementation of the Guidelines for Introducing Independent Directors to the Board of Directors for Listed Companies in August 2001 and the Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies in January 2002. The CSRC specifically mandated that all listed companies should have appointed at least one-third of independent members to their boards by 2003 and enforced strict board meeting attendance requirements. Second, the recent financial crisis contributed to the failure of many large businesses and a significant decline in economic activity and led to an abnormal global economic recession in 2008. Therefore, the period 2004–2007 is appropriate for us to study the association between corporate governance mechanisms and IEM, as relatively standardized corporate governance systems were in existence in China during this period, and at the same time, there were no major economic shocks in the market. For a firm to be included in a certain year's observation, its stocks must have been traded on the exchanges in the previous year or earlier and must have issued its quarterly reports during the period. We initially obtained 17,565 firm-quarter observations. After deleting observations with missing values and industry sections with insufficient observations for the Jones model estimation, we obtained the final sample of 13,036 firm-quarter observations.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of all variables with winsorization of the top and bottom 0.5% of nonbinary variables. Following the aforementioned approach to distinguish from total earnings management, the observations for our three different specifications of IEM account for, on average, 47.59%, 27.34%, and 26.74% of the total 13,036 firm-quarter observations, which indicate that managers’ earnings management through the use of discretionary accruals in the Chinese market is not just opportunistic, whereas, to a reasonably large extent, their engagement in earnings management is informative in that it conveys their private information about the firms’ future earnings or cash flows to external stakeholders. These data also suggest that simply attributing earnings management to an opportunistic perspective may be severely biased in interpreting managerial motivations and the consequences of earnings management in many previous studies.

| Panel A: Sample selection | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All firm-quarter observations 2004–2007 | 17,565 | |||||||

| Less: Observations with missing values | 2,366 | |||||||

| Observations in an industry section insufficient for Jones Model | 2,163 | |||||||

| Final sample | 13,036 | |||||||

| Panel B: Descriptive statistics of variables | ||||||||

| Variable | N | Mean | 1st Quartile | Median | 3rd Quartile | MIN | MAX | STD |

| IEM1 | 13036 | .4759 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | .4994 |

| IEM2 | 13036 | .2734 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | .4457 |

| IEM3 | 13036 | .2674 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | .4426 |

| LSH | 13036 | .4059 | .2759 | .3893 | .5420 | .0518 | .8500 | .1635 |

| LSH2_5 | 13036 | .1607 | .0507 | .1356 | .2556 | .0020 | .5387 | .1252 |

| MSH | 13036 | .0013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .3100 | .0147 |

| NONTRD | 13036 | .5702 | .4952 | .5924 | .6640 | 0 | .8523 | .1300 |

| CROLIS | 13036 | .0220 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .1467 |

| CEOCHR | 13036 | .1100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .3160 |

| INDDIR | 13036 | .3439 | .3333 | .3333 | .3636 | .2119 | .6667 | .0469 |

| SUPER | 13036 | 1.3662 | 1.0986 | 1.0986 | 1.6094 | 0 | 2.5600 | .3246 |

| BODMEET | 13036 | 7.6547 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 19 | 2.9774 |

| SBMEET | 13036 | 3.4957 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 12 | 1.6641 |

| SAGM | 13036 | .5708 | .4841 | .5889 | .6672 | .0934 | .8756 | .1351 |

| LNASSET | 13036 | 21.3104 | 20.6508 | 21.2210 | 21.8922 | 18.5400 | 24.4200 | .9707 |

| ROA | 13036 | .03360 | .0112 | .0323 | .0618 | −.2023 | .2639 | .0644 |

| LEV | 13036 | .4983 | .3749 | .5104 | .6258 | .0100 | 1.0000 | .1811 |

| SEO | 13036 | .0600 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .2410 |

| ST/PT | 13036 | .0700 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .2500 |

| BigN | 13036 | .0700 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .2500 |

- Notes: 1) All variables are as defined in Table 1; 2) IEM and yearly effects include three-quarterly data for each firm year, that is, the first three quarters in a year with a total of 13,036 firm-quarter observations, assuming the fourth quarter data are the annual reports.

In our sample, the largest owner holds, on average, 40.59% of total shares being issued, which is much larger than that in many other countries. Equity shares held by the second to fifth largest shareholders (blockholders) account for 16.07%, suggesting that they may exercise moderate monitoring over the largest shareholder and senior managers. Nontradable shares were still prevalent for the years studied, accounting for, on average, 57.02% of the total shares, although circulation of nontradable shares has been implemented since mid-2006. 15 Managerial ownership in the sample firms is approximately 0.13%, as managerial shareholdings and the performance stock option scheme are rare for Chinese firms under the existing socialism doctrine that discourages individual ownership. On average, 2.20% of sample firms are cross-listed in overseas stock exchanges, indicating that the internationalization of Chinese listed firms is insufficient. Splitting the positions of CEO and BOD chairman seems to be the norm among the listed firms in China during the test period, as only in 11% of the listed firms were the two positions held by the same person. Independent directors account for, on average, 34.39% of all directors, thus fulfilling the requirement of a minimum of one-third of independent directors on the BOD. The number of SB members (supervisors) is larger than that of independent directors, as the ratio of supervisors to total directors is 44.14% (and the log value of the number of SB members is 1.366). The BOD and the SB, on average, have 7.66 and 3.50 meetings every year, respectively, demonstrating that the BOD is more active than the SB. On average, 57.08% of the total registered shares attend annual general meetings. However, we should not simply conclude that shareholders actively exercise their rights at the annual meetings in China; rather, this may be because shareholding is highly concentrated within a few large shareholders who are very likely to show up and dominate at the annual general meetings. For control variables, the average size of listed firms in terms of total assets is RMB 1,796 million (log value = 21.31). The average return on assets for the Chinese listed firms is 3.36%, not an impressive profitability in general. The average leverage ratio is 49.83%, indicating that Chinese firms are highly leveraged. In the sample, the number of observations is similar over the test period, with a slight increase in more recent years, probably because some new firms underwent IPOs in the years examined. Approximately 6% of the sample firms had seasonal rights issuing in the test period, and 7% of the listed firms were subject to special market trading treatments (ST/PT).

Table 3 presents the Pearson correlations among the test and explanatory variables. IEM (including the varied specifications of IEM1, IEM2, and IEM3) is negatively related to the largest shareholder (LSH) (coefficient = −0.201, at the 1% significance level). As predicted, IEM is positively and significantly related to the shareholding of the second to fifth largest shareholders (LSH2–5), and the same result is found for the relationship between managerial ownership (MSH) and IEM. Managerial shareholdings can help align the interests of managers and shareholders and reduce agency conflict and information asymmetry, thus prompting managerial IEM. However, the higher the portion of nontradable shares, the less transparent the financial disclosures and the less likely it is that managers will pursue IEM. A positive correlation between IEM and cross-listing indicates that firms with shares listed in overseas markets tend to reveal more inside information to outside stakeholders. The negative association between the duality of CEO and BOD chairman (CEOCHR) and IEM suggests that splitting the two positions will increase IEM. More independent directors or more supervisors induce a higher chance of signalling inside information through managerial IEM. Table 3 also demonstrates that the active function of the BOD and the SB (more meetings in a year) contributes positively to managers’ communication of private information to external investors, as they are positively correlated with IEM. The correlations between SAGM and different IEM specifications (e.g., IEM1, IEM2, and IEM3) are somewhat inconsistent. A more convincing relationship between these two variables should be obtained from regression analyses. Taken together, these correlation results are consistent with our overall proposition that better function of corporate governance mechanisms can motivate and facilitate managers to engage in IEM in quarterly reporting to convey private information about their firms’ future earnings potential to outside stakeholders.

| IEM1 | IEM2 | IEM3 | LSH | LSH2_5 | MSH | CEOCHR | BODMEET | SBMEET | NONTRD | INDDIR | SUPER | SAGM | CROLIS | LNASSET | ROA | LEV | SEO | ST | BigN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEM1 | 1.000*** | |||||||||||||||||||

| IEM2 | .644*** | 1.000*** | ||||||||||||||||||

| IEM3 | .412*** | .537*** | 1.000*** | |||||||||||||||||

| LSH | −.201*** | −.142*** | −.156*** | 1.000*** | ||||||||||||||||

| LSH2_5 | .182*** | .145*** | .181*** | −.583*** | 1.000*** | |||||||||||||||

| MSH | .046*** | .063*** | .064*** | −.081*** | −.012 | 1.000*** | ||||||||||||||

| CEOCHR | −.060*** | −.071*** | −.087*** | −.066*** | .050*** | −.017* | 1.000*** | |||||||||||||

| BODMEET | .092*** | .134*** | .100*** | −.078*** | .020** | .016* | .005 | 1.000*** | ||||||||||||

| SBMEET | .078*** | .109*** | .081*** | −.028*** | −.031*** | .000 | .002 | .264*** | 1.000*** | |||||||||||

| NONTRD | −.118*** | −.122*** | −.087*** | .504*** | .193*** | −.120*** | −.026*** | −.101*** | −.105*** | 1.000*** | ||||||||||

| INDDIR | .066*** | .086*** | .077*** | −.052*** | .040*** | .004 | .041*** | .059*** | .070*** | −.055*** | 1.000*** | |||||||||

| SUPER | .060*** | .086*** | .077*** | .035*** | −.013 | −.018** | −.086*** | −.048*** | .062*** | .023*** | −.073*** | 1.000*** | ||||||||

| SAGM | −.033*** | .005 | −.002 | .536*** | .133*** | −.040*** | −.051*** | −.077*** | −.052*** | .656*** | −.022*** | .074*** | 1.000*** | |||||||

| CROLIS | .129*** | .182*** | .194*** | .073*** | .207*** | −.013 | −.019** | .064*** | .050*** | −.034*** | .056*** | .061*** | .103*** | 1.000*** | ||||||

| LNASSET | .059*** | .138*** | .084*** | .190*** | −.164*** | −.014 | −.061*** | .061*** | .063*** | −.076*** | .023** | .198*** | .095*** | .262*** | 1.000*** | |||||

| ROA | .091*** | .144*** | .098*** | .164*** | −.035*** | .038*** | −.034*** | −.066*** | .024*** | .067*** | .007 | .049*** | .231*** | .081*** | .207*** | 1.000*** | ||||

| LEV | −.032*** | −.022** | −.035*** | −.124*** | .013 | −.010 | .026*** | .155*** | .016* | −.083*** | .036*** | .028*** | −.159*** | −.007 | .212*** | −.352*** | 1.000*** | |||

| SEO | .008 | .017** | .008 | −.015* | .008 | −.006 | .005 | .021** | −.002 | −.014* | .037*** | .005 | .045*** | −.002 | .054*** | .088*** | .074*** | 1.000*** | ||

| ST/PT | −.031*** | −.055*** | −.047*** | −.055*** | .028*** | −.013 | .073*** | .063*** | .036*** | −.006 | .007 | −.084*** | −.088*** | −.028*** | −.176*** | −.292*** | .155*** | −.023*** | 1.000*** | |

| BigN | .082*** | .102*** | .109*** | .075*** | .044*** | −.018** | −.038*** | .048*** | .031*** | .001 | .031*** | .065*** | .104*** | .385*** | .353*** | .159*** | −.046*** | .027*** | −.065*** | 1.000*** |

- Notes: 1) This table presents the Pearson correlation matrix; 2) All variables are as defined in Table 1; 3)

- ***, **, and * denote the significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively.

The positive correlation between firm size and IEM implies that large firms are more likely to signal inside information to users than smaller firms. The positive correlation between ROA and IEM may indicate that more profitable firms, compared with their counterparts, are more willing to convey inside information through IEM. In addition, highly leveraged firms are less likely to pursue IEM in their financial reporting, which may be due to concern over abrupt market reaction to their financial stress. We do not find any serious multicollinearity problems, as no correlation coefficient exceeds 0.7 in our sample (Belsley et al., 1980).

Regression Results

Tables 4 to 6 report multivariate regression results for our IEM models. Columns 1 to 3 estimate the results for the first-, second-, and third-quarter observations, respectively. Table 4 shows the regression results for the specification of IEM1 (Model 1). We find that the largest shareholder (LSH) is negatively associated with IEM for all three reporting quarters (coefficient = −0.022, −0.025, and −0.024 for the three quarters, respectively; all are significant at the 1% level), indicating that a larger controlling owner (high ownership concentration) generally impedes managerial motivation to pursue IEM. The second to the fifth largest owners’ shareholding (LSH2–5) has a positive coefficient (coefficient = 0.013, 0.011, and 0.016, respectively, at varied significance levels), indicating that other large shareholders (blockholders) can effectively monitor the largest shareholder and the management and require more transparent or informative reporting. Firms with a higher managerial shareholding are more likely to signal private information to outside investors (positive and significant for the first and third quarters, but insignificant for the second quarter), indicating that the alignment of interest between managers and shareholders improves transparency. 14 A great percentage of nontradable shares tends to decrease the chance of IEM (coefficient = −1.505, −1.590, and −1.384, respectively; all are significant at the 1% level). Cross-listing increases the possibility of IEM (coefficient = 1.629, 1.667, and 2.361, respectively; all are at the 1% significance level). These results support our overall proposition regarding the association between corporate governance and managerial IEM, especially Hypothesis 1, that sound corporate governance mechanisms in respect of equity capital structure positively affect the likelihood of IEM, as those equity structure arrangements that enhance corporate governance and reduce information asymmetry will more likely lead to IEM, and vice versa.

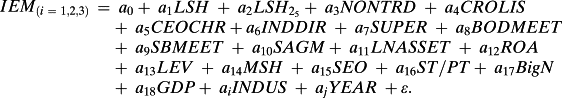

| IEM1 = a0 + a1LSH + a2LSH2_5 + a3MSH + a4NONTRD + a5CROLIS + a6CEOCHR + a7INDDIR + a8SUPER+ a9BODMEET + a10SBMEET + a11SAGM + a12LNASSET + a13ROA + a14LEV + a15SEO + a16ST/PT + a17BigN + aiINDUS + ajYEAR + ε | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | 1st Quarter | 2nd Quarter | 3rd Quarter |

| Constant | −2.868*** | −2.315*** | −2.928*** |

| LSH | −.022*** | −.025*** | −.024*** |

| LSH2_5 | .013** | .011* | .016*** |

| MSH | 8.103** | 2.718 | 7.085** |

| NONTRD | −1.505*** | −1.590*** | −1.384*** |

| CROLIS | 1.629*** | 1.667*** | 2.361*** |

| CEOCHR | −.570*** | −.424*** | −.391*** |

| INDDIR | 2.099*** | 1.892*** | 2.749*** |

| SUPER | .323*** | .361*** | .275*** |

| BODMEET | .044*** | .046*** | .052*** |

| SBMEET | .045*** | .049** | .059*** |

| SAGM | .012*** | .015*** | .013*** |

| LNASSET | .099** | .077* | .088** |