How Do Auditors Address Control Deficiencies that Bias Accounting Estimates?†

Abstract

Auditors commonly rely on reviewing management's estimation process to audit accounting estimates. When control deficiencies bias the estimation process by creating omissions of critical inputs, standards require that auditors replace or supplement review of management's estimation process with tests that can identify the omissions. Importantly, overreliance on reviewing management's estimation process when it has been biased by a control deficiency can result in auditor acceptance of an inappropriate accounting estimate. We use an experiment to examine whether auditors recognize the insufficiency of increased sampling of a biased estimation process and their selection of alternative tests to replace or supplement review of the biased estimation process. We find that a significant minority (33 percent) of Big 4 senior auditors erroneously increase tests of management's biased estimation process. We also find that auditors have difficulty selecting alternative tests to replace or supplement review of management's biased estimation process, frequently choosing tests that are either ineffective or inefficient. Our findings suggest that auditors often reach inappropriate judgments about the capability of audit evidence to address control deficiencies and that nonsampling risk (judgment risk) may be a larger risk than auditors realize.

1 Introduction

The well-established relation between internal control deficiencies and audit evidence appears straightforward. When auditors identify significant internal control deficiencies, they modify substantive tests to address the increased risk of material misstatement (PCAOB 2007, ¶B6; IAASB 2008a, ¶A46; AICPA 2006b, ¶121; AICPA 2006c, ¶¶70-74).1 Yet, audit inspection reports indicate that auditors often fail to appropriately modify substantive tests when ineffective controls are discovered (PCAOB 2008), and audit partners we interviewed agree that auditors often have difficulty modifying substantive tests when responding to identified control deficiencies. To shed light on the underlying reasons for this difficulty, we design a contextually rich experimental case and examine how auditors map a control deficiency into modifications of substantive tests.

Audits of accounting estimates provide the context for our study. Accounting estimates comprise much of the quantitative information in financial statements and represent an important component of auditor judgment and decision making (Griffith, Hammersley, and Kadous 2013; Peecher, Solomon, and Trotman 2010). In addition, audit inspections frequently attribute audit errors in accounting estimates to overreliance on incomplete or inaccurate management processes, suggesting a practical context where auditors fail to appropriately modify substantive tests for control deficiencies (PCAOB 2010b, 2008). We examine control deficiencies that cause errors of omission in an estimation process, resulting in an incomplete and biased estimation process. Our focus is on whether auditors recognize the insufficiency of reviewing the biased estimation process and how they select alternative tests to replace or supplement such review.

We first analyze auditor judgments about the insufficiency of increased review of management's biased estimation process (increasing sample size) following a control deficiency. When control deficiencies cause omissions in management's estimation process, standards and research indicate that testing within the process cannot identify omissions from the process (AICPA 1980, ¶17; Bell, Peecher, and Solomon 2005, 28; Griffith et al. 2013). Since required internal control deficiency documentation should identify the bias in the estimation process and auditors have well developed knowledge structures for internal control errors, we expect that most auditors will recognize that increasing sample size is insufficient (PCAOB 2007; Zimbelman 1997). However, psychology research finds that over 20 percent of people select biased evidence sources even after they are told of the bias (Soll 1999). Assuming that auditors have evidence beliefs in keeping with the general population, we expect that a significant minority of auditors make a similar mistake and judge that increasing sample size is sufficient.2

We also expect that seeing substantive test results from reviews of the biased estimation process influences auditors' tendency to mistakenly increase such review. Standards allow “dual-purpose” tests that combine substantive tests and tests of control (IAASB 2008a, ¶22; AICPA 2006c, ¶33).3 As such, the potential exists for auditors to see substantive test results before addressing the control deficiency. Substantive tests from reviewing the biased estimation process generate falsely favorable results, because the tests will agree to the flawed estimate produced, but neither the process nor the test includes the omissions. Ex ante, it is unclear how auditors will react to seeing falsely favorable substantive test results that come from reviewing the biased estimation process. Competing theories suggest that auditors may either be misled because the test results are representative of a properly functioning process or be more aware of the bias because the falsely favorable results confirm the bias (Hackenbrack 1992; Hoffman and Patton 1997; Glover 1997; Wegener and Petty 1995, 1997).

We test our expectations using a case-based experiment with 81 Big 4 senior auditors. The experimental context is revenue recognition for long-term sales contracts determined by the percentage-of-completion method. Seeded control deficiencies, which systematically increase the likelihood of overstating current revenue, stem from omissions to management's estimation process (AICPA 1981). Prior to identifying the control deficiencies in the estimation process, planned substantive tests involve reviewing management's biased estimation process. As predicted, we find a significant minority (33 percent) of auditors judge that increasing sample size sufficiently addresses the control deficiency. We also find that seeing the falsely favorable substantive test results, on average, does not influence auditors' tendency to increase sample size. All reported findings are robust across auditor experience classifications. In addition, a supplemental sample of 14 managers produces a pattern of responses similar to our main results.

Next, we analyze how auditors select alternative tests to replace or supplement reviewing management's incomplete and biased estimation process. Standards and research indicate that auditors must select a test based on independent evidence, outside the biased estimation process, that is capable of identifying the omission (AICPA 1980, ¶17; Bell et al. 2005, 28).4 Further, the type of independent evidence needed to identify the omission depends on the omission's source. We analyze omissions from two different sources that cause bias in the estimation process, omitted data from externally prepared documents held by the client and omitted management judgment inputs.

If the omission in management's estimation process stems from data found on externally prepared documents held by the client, control deficiency documentation should identify the specific documents involved in the omission (PCAOB 2004). Identifying these documents should illustrate the effectiveness of using them to adjust the estimation process, thereby offering the auditor both a means of identifying the bias and a mental model of how to audit the biased process. Transfer learning theory suggests that this mental model will make auditors realize that generating an independent estimate would also effectively identify the bias (Cree and Macaulay 2000; Ellis 1965; Haskell 2001). Faced with two effective alternatives, auditors should choose using documents to adjust the estimate because it is more efficient than developing an auditor-generated estimate. However, following Payne, Bettman, and Johnson (1993), we assume that auditors act based on their individual choice preferences when trading off two effective solutions. As such, we expect that auditors equivalently select between using externally prepared documents to adjust the estimate and developing an auditor-generated estimate.

If the omission stems from management's judgment inputs to the estimate, developing an auditor-generated estimate provides the most effective independent evidence, because externally prepared documents are unlikely to contain the judgment evidence needed to adjust the estimate (IAASB 2008b, ¶¶A87, A91, A124–25). Here, control deficiency documentation focuses on the judgment omission, as opposed to an evidence source that could identify the omission, because deficiency documentation is not required to include alternative test strategies (PCAOB 2004). Without a specific document, auditors must create a mental model of how to audit the biased estimation process on their own, a task that imposes high cognitive demand. This in turn makes them susceptible to using heuristics (Kool, McGuire, Rosen, and Botvinick 2010). Given that the most common audit tests involve examining documents held by the client, we expect that the availability heuristic leads auditors to make the less effective choice of using documents to adjust the estimate, instead of the more effective choice of developing an auditor-generated estimate (Blay 2005; Tversky and Kahneman 1974).

We test these expectations using the previously discussed sample and experimental case. As predicted, when the bias is from externally prepared documents, we find that about one-half the auditors (54 percent) choose the more efficient alternative test, adjusting the estimate using documents. When the bias is from management judgment inputs, we find that most auditors (63 percent) choose to adjust the estimate using documents, even though this alternative is less effective than developing an auditor-generated estimate. Together, the results suggest that auditors often make inefficient or ineffective alternative test choices depending on the source of omission caused by the control deficiency.

Our study contributes to both practice and research. For practice, we provide evidence about the relation between control deficiencies and substantive tests in the integrated audit. Prior to SOX, auditors rarely relied on controls, potentially causing gaps in their ability to map internal control deficiencies into substantive test modifications (Allen, Hermanson, Kozloski, and Ramsay 2006; O'Keefe, Simunic, and Stein 1994; Waller 1993). Anecdotally, regulators have expressed concerns about such gaps. We provide theory-consistent empirical evidence that auditors often reach questionable, optimistic judgments about the capability of audit evidence to address control deficiencies. For research, we extend Griffith et al.'s (2013) field study data by providing experimental evidence about how overrelying on management's estimation process can occur when testing accounting estimates. In addition, we provide new empirical evidence that nonsampling risk (judgment risk) may be a larger risk than auditors realize, both confirming theory (Peecher, Schwartz, and Solomon 2007; Bell et al. 2005) and building on Budescu, Peecher, and Solomon's (2012) simulation results.

The next section develops hypotheses. Section 3 describes the experimental methods and section 4 presents results. Section 5 discusses the study's implications and limitations.

2 Background and hypotheses

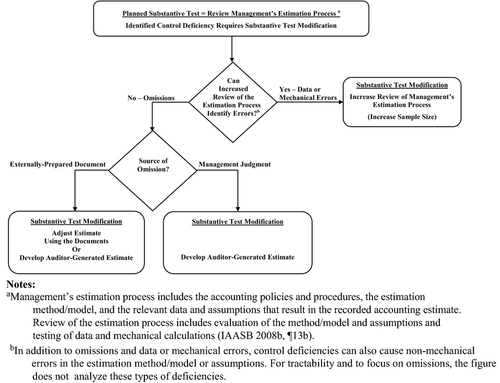

Control deficiencies increase the risk of material misstatement, and auditors must modify substantive tests to offset this risk (PCAOB 2007, ¶B6; IAASB 2008a, ¶A46; AICPA 2006b, ¶121; AICPA 2006c, ¶¶70–74). Modifications involve increasing the sample size of planned tests or selecting alternative test strategies. As shown in Figure 1, when auditors plan on auditing accounting estimates by reviewing management's estimation process and subsequently identify a control deficiency, substantive test modifications depend on the control deficiency's source. The standards-based decision tree in Figure 1 indicates that increasing sample size is only sufficient if the estimation process can identify the errors caused by the control deficiency. If the estimation process cannot identify these errors, then auditors must select a test based on independent evidence, outside the estimation process, that is capable of identifying the errors (AICPA 1980, ¶17; Bell et al. 2005, 28). Figure 1 prescribes the two decision points when errors of omission bias management's estimation process: the first being the sufficiency of increasing sample size and the second being the selection of alternative tests to replace reviewing the biased estimation process.

Contract revenue recognition provides an example illustrating the decisions in Figure 1. Management's estimation process for contract revenue recognition involves estimating the contract percentage of completion based on aggregating contract costs to date and estimating future costs (AICPA 1981). Reviewing management's estimation process for contract percentage of completion represents the most common substantive test for this estimate (Larson and Brown 2004; Griffith et al. 2013). If a control deficiency causes only mechanical errors in the calculation of contract percentage of completion, an increased sample of management's estimation process, tested with the correct calculation, can identify errors in the estimate. Conversely, a control deficiency that causes omissions of future costs in the calculation of contract percentage of completion cannot be identified by reviewing management's estimation process because the process only includes the costs that management has included in the estimate. Thus, increased review of the biased estimation process is insufficient. Instead, auditors need to find an evidence source outside management's estimation process that will identify the particular omission.

Increased sampling of a biased estimation process

We expect that most auditors understand bias caused by a control deficiency. Audit standards require documentation of each identified control deficiency to support the internal control audit opinion (PCAOB 2007). This documentation identifies the nature of omissions in the estimation process, creating awareness that the process is in fact biased. Auditors also frequently encounter errors created by control deficiencies, so their knowledge structures for such errors are well developed (Zimbelman 1997). Finally, higher order strategic reasoning is not necessary to evaluate bias caused by control deficiencies, as management does not attempt to hide such bias (Wilks and Zimbelman 2004). Because we expect that most auditors understand bias caused by control deficiencies, we expect that most auditors recognize the insufficiency of increased sampling of a biased estimation process.

However, we also expect a significant minority of auditors will consider increased sampling of a biased process to be sufficient. Across several experiments, Soll (1999) examines how people evaluate biased evidence in tasks involving military intelligence, blood tests, and weight-measuring scales. He finds that some people systematically select and rely on biased evidence. In one of the experiments, Soll (1999) prepped his participants by defining the concept of biased evidence and identifying the amount of bias in the experimental task. In this setting, Soll (1999) finds that just over 20 percent of participants still increase testing of a biased evidence source. When queried as to why they did this, participants offer logic that precluded replacing the biased evidence, such as the belief that consistent use of an evidence source holds constant confounding attributes and therefore is a superior strategy regardless of the type of error in the evidence. Soll (1999) concludes that some people have systematic discrepancies between their beliefs about evidence and the normative use of a biased evidence source.

Hypothesis 1. A significant minority of auditors will judge that increased sampling of a biased estimation process is a sufficient response to the control deficiency that caused the bias.

If auditors combine tests of control and substantive tests, as allowed by standards, then the control deficiency can be discovered after auditors have begun substantive tests (IAASB 2008a, ¶22; AICPA 2006c, ¶33). Although we expect that Hypothesis 1 applies regardless of the presence or absence of test results, we also expect that seeing test results will influence auditor judgment. In the presence of test results, auditors possess two pieces of information when they determine the sufficiency of increased sampling of the biased process to address the control deficiency: (1) substantive test results from the review of management's estimation process, and (2) internal control documentation indicating that a deficiency has biased the estimation process. When the control deficiency is an omission from the estimation process, substantive test results will agree to the recorded accounting estimate, but neither the substantive test results nor the accounting estimate will include the omitted data. Such substantive test results are falsely favorable, and theory supports two competing predictions regarding auditor behavior upon seeing these substantive test results.

Hypothesis 2a. In the presence, as compared to the absence, of substantive tests results from a biased estimation process, auditors are more likely to judge that increased sampling of the biased estimation process is a sufficient response to the control deficiency that caused the bias.

Hypothesis 2b. In the presence, as compared to the absence, of substantive tests results from a biased estimation process, auditors are less likely to judge that increased sampling of the biased estimation process is a sufficient response to the control deficiency that caused the bias.

Selecting alternative tests

When control deficiencies cause omissions in management's estimation process, biasing the accounting estimate, auditors should acquire evidence independent of the flawed estimation process to identify the bias (PCAOB 2007, ¶B6; IAASB 2008b, ¶¶A87, A124–25). As shown in Figure 1, such evidence can take one of two forms: (1) documents held by the client but created by parties external to the client, or (2) an independently developed estimate generated by the auditor (IAASB 2008b, ¶A91). If the source of bias stems from omissions found on externally prepared documents, either using these documents to adjust the estimate or an auditor-generated estimate can effectively identify the bias (IAASB 2008b, ¶¶A87, A91). Alternatively, if the source of bias stems from management judgment inputs, a setting in which externally prepared documents are incapable of identifying the bias, only an auditor-generated estimate can effectively identify the bias (IAASB 2008b, ¶¶A87, A91, A124–25; AICPA 1980, ¶17).

When the source of a control deficiency stems from omission of data found on externally prepared documents, the deficiency documentation should describe the specific documents involved, the evidence examined and conclusions reached (PCAOB 2004). Consequently, the control deficiency documentation identifies the documents needed to adjust the estimate and thereby detect the bias in management's estimate. With access to documentation that identifies both the bias in the estimation process and the externally prepared documents at their source, we expect that auditors readily understand that they could adjust the estimate using the documents. Identifying an effective test helps auditors create a mental model of how to audit the biased process, facilitating transfer learning (Cree and Macaulay 2000; Ellis 1965; Haskell 2001).5 We expect that knowledge about the effectiveness of using externally prepared documents to detect the bias in the estimation process transfers to evaluating the effectiveness of developing an independent estimate to detect the bias. In sum, auditors are likely to recognize that using the documents to adjust the estimate is effective and then transfer such recognition to conclude that independently developing their own estimate is also effective.

Hypothesis 3a. Auditors will choose equally between using documents to adjust a biased client estimate and developing an auditor-generated estimate when modifying substantive tests to address control deficiencies stemming from omitted data found on externally prepared documents.

Control deficiencies can also stem from omissions of a critical management judgment to the estimation process. In this case, independently developing an estimate is a more effective substantive test modification than using documents to adjust the estimate, because an externally prepared document will not contain the omitted judgment.6 Moreover, control deficiency documentation is unlikely to identify the need for an auditor-generated estimate, because deficiency documentation does not identify the tests needed to address the deficiency (PCAOB 2004). As such, auditors must rely on their cognitive resources, including long-term memory, to determine the appropriate procedure for detecting the bias in the estimation process.7

Hypothesis 3b. A majority of auditors will choose using documents to adjust a biased client estimate versus developing an auditor-generated estimate when modifying substantive tests to address control deficiencies stemming from omitted management judgment inputs.

The implications of Hypothesis 3b are troublesome. Specifically, the predicted number of auditors choosing to adjust the estimation process with externally prepared documents is worrisome, because the diagnostic value of doing this is very low when the bias stems from management judgment inputs.

3 Experimental method

Participants

Eighty-seven auditors attending one Big 4 firm's national training for experienced audit seniors participated in the study. Though the audit of estimates is complex, seniors execute nearly every step in the audit process, including selecting an audit approach (Griffith et al. 2013). Further, the audit partner who reviewed the experimental materials indicated that senior auditors should be able to respond correctly to the experiment's biased accounting estimates.

Experimental task and manipulations

We employ a between-participants experimental design with two treatments: (1) substantive test results based on reviewing management's incomplete and biased estimation process (absent or present), and (2) the source of omissions that create bias (externally prepared documents or management judgments). We describe the treatments in sequence within the experimental task. We randomly assign participants to experimental treatments and ask them to complete a case study.8

All participants receive the same background materials, which describe the audit client as a publicly traded company that designs, manufactures, and installs automated production systems. Sales contracts for the production systems routinely take a year or more to complete, and revenue for uncompleted contracts is recognized via the percentage-of-completion method. The materials offer a detailed explanation of the process for estimating and recognizing revenue.9 Finally, the background materials describe interim audit judgments and initial risk assessments, interim control tests with no deficiencies noted, and planned substantive tests for contract revenue.

Systematically understating estimated cost to complete results in systematically overstating revenue recognized for contracts in progress. Based on magnitude and likelihood of financial misstatement, the audit team assessed an internal control significant deficiency.

Controls over cost-to-complete estimates had been effective prior to the fourth quarter's personnel change. So, the planned substantive tests for estimated cost to complete appropriately involve reviewing management's estimation process as documented on engineering's cost analysis reports. However, the control deficiency's omissions create bias in engineering's cost analysis reports, making increased sampling of the cost analysis reports insufficient and requiring the selection of alternative tests.

In the first treatment, we manipulate the absence/presence of substantive test results from reviewing the biased cost analysis reports. In one condition, the case informs participants that planned tests have not yet been completed. In the other condition, the case informs participants that planned substantive tests and tests of control were performed jointly. When tests are performed jointly, the case describes the substantive test results from reviewing the biased cost analysis reports, which validate management's estimated recognized revenue and support a conclusion that revenue is fairly stated.10 All participants evaluate whether it is sufficient to increase the sample size of the tests from the initial audit plan in response to the control deficiency.

In the second treatment, we manipulate the source of bias in the cost analysis reports. In one condition, the lead engineer fails to perform procedures examining “documents from subcontractors on estimates to complete their share of the work.” In this control deficiency, omissions in the cost analysis reports stem from cost-to-complete estimates found on externally prepared documents held by the client. In the other condition, the lead engineer fails to perform procedures “corroborating engineering estimates with estimates provided by project supervisors.” In this control deficiency, omissions in the cost analysis reports stem from management judgment inputs about field-determined future production costs. Participants respond to the conditions in this treatment by selecting an alternative to reviewing the biased cost analysis reports. The alternatives involve either using the externally prepared documents to adjust the estimate (vouching) or developing an auditor-generated estimate by confirming the entire cost-to-complete estimate with the customer (confirming).11

When the source of bias is an omission from externally prepared documents, both vouching and confirming should effectively identify the bias, though vouching is more efficient than confirming.12 For bias from an omission of management judgment, confirming should effectively identify the bias. Vouching is less effective because it will only verify the subcontractor component of the estimate contained on documents, not the field-determined future production costs. As a result, vouching will not verify the entire cost-to-complete estimate; and thus for bias stemming from management judgment inputs, confirming is more effective.

To verify our prescriptive response, we conducted structured interviews with five audit partners from different international firms who all have percentage-of-completion experience.13 Each partner indicated that increased sampling of the biased cost analysis reports was insufficient and that auditors should perform alternative substantive tests. With regard to choosing alternative substantive tests, each audit partner indicated that vouching is the preferred procedure when bias stems from externally prepared documents, because it is effective and less costly than confirming. Each audit partner also indicated that confirming is the preferred procedure when bias stems from management judgment inputs, because only confirming can account for all project costs, not just those found on externally prepared documents.

Experimental materials were pilot tested on graduate students with audit experience and changed where necessary. An audit partner from the firm that provided participants reviewed the final version of the materials. The partner noted the realism of the case and indicated that it is representative of judgments made on integrated audits.

Experimental administrators read a script introducing the experiment and distributed envelopes containing an information sheet, general instructions, and three packets of materials. Each packet was retrieved from the envelope, completed, and replaced in the envelope before the next packet was begun. Packet one contained the experimental case and the related response scales. Packet two contained a training tutorial and a copy of the experimental case with the related response scales. Packet three contained the experimental checks, debriefing questions, and demographic questions. Administrators monitored completion of the task and collected the completed packets. The experiment took about one hour to complete.

Dependent variables

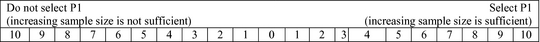

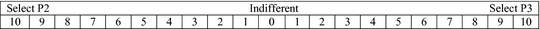

Auditor judgments are captured on 21-point bipolar scales that range from − 10 to + 10 with zero as the midpoint (see Appendix). For the dependent variable capturing the sufficiency of increasing sample size judgments, scale anchors are “increasing sample size is not sufficient” and “increasing sample size is sufficient.” For the dependent variable capturing alternative audit procedure judgments, scale anchors represent “vouching” and “confirming.” To enhance the clarity of the results discussion, we use count data based on the number of auditors on each side of the bipolar scale midpoint in our primary analyses. All results are inferentially identical when using the original scale data (not tabulated).

4 Results

Table 1 presents the participant profile. After eliminating six incomplete responses, our final sample is 81 auditors.14 The auditors had an average 43.2 months (3.5 years) of experience. On average, they chose substantive test procedures on six (6.3) clients, participated in planning the audit on six (5.7) clients, participated in four (4.1) SOX 404 audits, and observed significant control deficiencies on two (2.1) clients. Additionally, the auditors changed audit plans in response to a control deficiency on an average of three (2.8) clients. Direct experience with percentage-of-completion accounting was relatively low at an average of 4.8 on a 21-point scale anchored on “none” and “a great deal.” However, the auditors assessed their understanding of the percentage-of-completion case materials high, at an average of 17.3 on a 21-point scale anchored on “not well” and “very well.”15 Auditor demographics and self-assessments do not vary across treatments (all p-values > 0.10). It appears that the auditor participants in our study are adequately experienced in evaluating control deficiencies and formulating revisions to audit plans, and they appear to have understood the case materials.

| Meana | Std. dev. | |

|---|---|---|

| Months of audit experience | 43.21 | 9.61 |

| Number of times involved in choosing substantive test procedures | 6.34 | 3.47 |

| Number of times involved in the planning phase of the audit | 5.72 | 2.85 |

| Number of SOX 404 audits | 4.12 | 2.80 |

| Number of clients with significant control deficiencies | 2.09 | 2.15 |

| Number of clients where a control deficiency changed the audit plan | 2.84 | 2.27 |

| Experience with the percentage-of-completion methodb | 4.81 | 6.38 |

| Understanding of percentage of completion in the case materialsb | 17.30 | 2.80 |

- Notes:aAuditor demographics and self-assessments do not vary across treatments (all p-values > 0.10).

- bSelf-assessments are made on 21-point scales with 20 representing high knowledge, experience, and understanding.

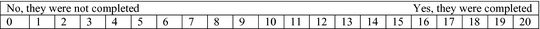

Manipulation and other checks

Manipulation checks, measured with 21-point scales ranging from zero to 20, verify that participants understood their assigned treatment. Scales are shown in the Appendix. Mean responses about whether auditors had already completed planned substantive tests were 1.7 (10.2) for the absence (presence) of results, on the correct end of the scale (t = 6.04, p < 0.001). Mean responses about the source of bias were 8.2 for the bias from externally prepared documents condition and 16.4 for the bias from management judgment condition, on the correct end of the scale (t = 5.97, p < 0.001).

Other experimental checks verify that the auditors understood the key elements of the experimental setting. To assure that auditors understood the revenue effect of the control deficiency, we asked if uncompleted contract revenue was “overstated” or “understated.” The mean response is 1.2 on the “overstated” end of the scale (scale point = 0) and response differences between treatments is insignificant (p = 0.34).16 We also asked two questions to assure that auditors understood the alternative tests for addressing the control deficiency. The first question asked whether the tests were “not different” (scale point = 0) or “one required confirmations, one did not” (scale point = 20). The mean response is 18.3 on the correct end of the scale with no difference between treatments (p = 0.41). The second question asked auditors about the “difference in the needed hours to complete” between vouching and confirming. The mean response is 17.4 on the “confirmation procedures required more hours” end of the scale (scale point = 20) with no difference between treatments (p = 0.45).

Hypotheses tests

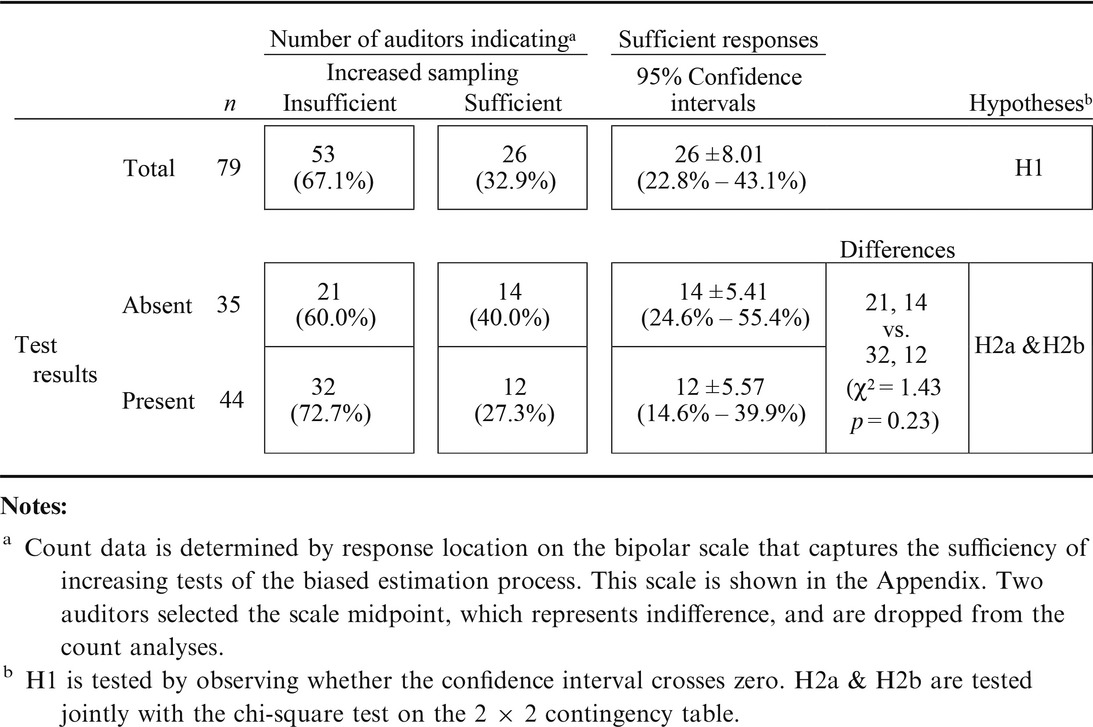

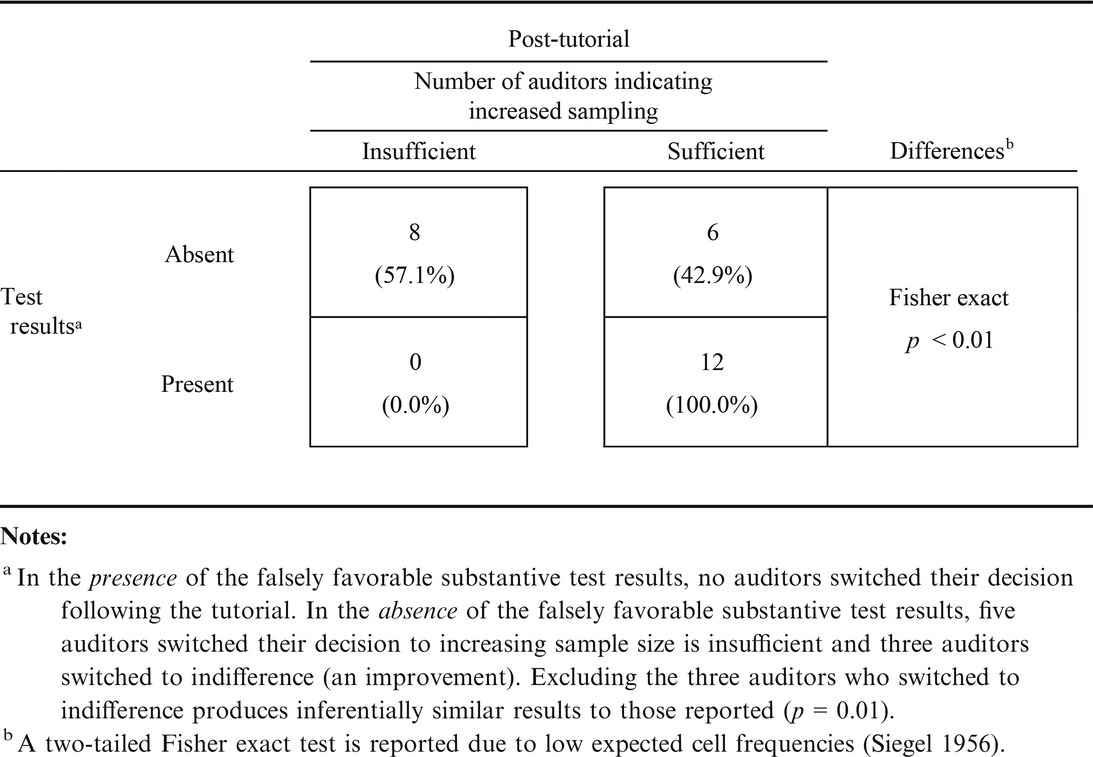

Hypothesis 1 indicates that a significant minority of auditors will judge that increased sampling of a biased estimation process is a sufficient response to the control deficiency that caused the bias. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, we find that 26 (32.9 percent) auditors judged that increased sampling is sufficient. To test Hypothesis 1, we apply a 95 percent confidence interval to the frequency count to evaluate whether or not the interval includes zero. As shown in Table 2 and supporting Hypothesis 1, we find that 26 ± 8.01 (22.8 percent–43.1 percent) auditors increased sampling of the biased estimation process to address the control deficiency. While most auditors judge that increased sampling is insufficient (53 vs. 26, χ2 = 9.23, p < 0.01), a significant minority believe the opposite. Similar to findings in the psychology literature, a significant minority of auditors choose to increase tests of the biased estimation process after being told explicitly that the process is biased.

Hypothesis 2a posits that in the presence of results from reviewing the biased estimation process, auditors are more likely to increase sampling of the biased process. Conversely, Hypothesis 2b posits that in the presence of results from reviewing the biased estimation process, auditors are less likely to increase sampling of the biased process. As shown in Table 2, our findings do not support either Hypothesis 2a or 2b. We find that 21 (14) auditors judge that increased sampling of the biased estimation process is insufficient (sufficient) in the absence of biased substantive test results. Conversely, 32 (12) auditors judge that increased sampling of the biased estimation process is insufficient (sufficient) in the presence of biased substantive test results. A chi-square test of proportion shows no difference exists between auditor sufficiency judgments across the absence versus presence of substantive test result conditions (χ2 = 1.43, p = 0.23, Table 2). We find that results from tests of the biased estimation process do not influence auditors' judgments about the sufficiency of increased testing of the process.

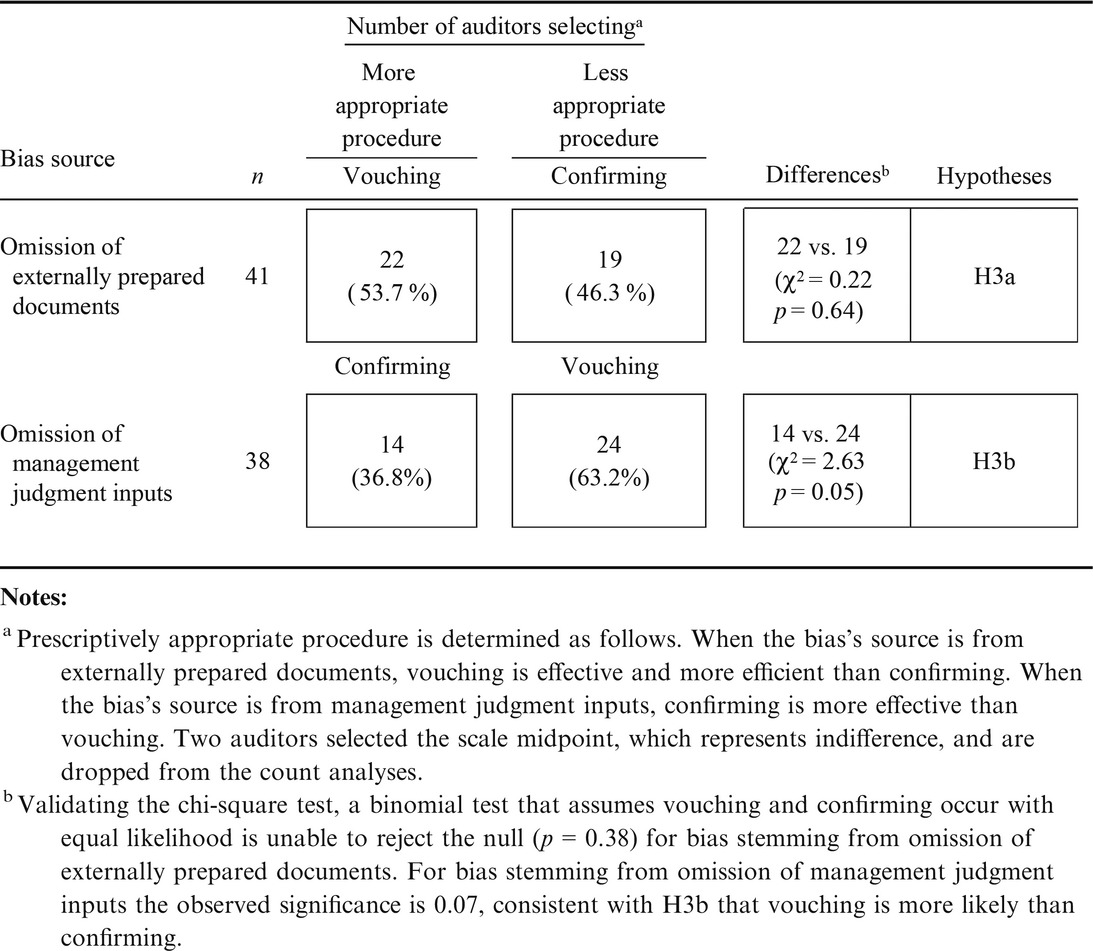

Hypothesis 3a posits that auditors choose equally between vouching and confirming when addressing bias stemming from the omission of externally prepared documents. As shown in Table 3 and consistent with Hypothesis 3a, we find that 22 of 41 (53.7 percent) auditors address the bias by choosing vouching, but this does not differ from the proportion who choose confirming (22 vs. 19, χ2 = 0.22, p = 0.64, two-tailed).17 Consistent with our theory, auditors choose equally between vouching and confirming, based apparently on their individual preferences.

Hypothesis 3b posits that most auditors choose vouching over confirming when addressing bias stemming from the omission of management judgment inputs. As shown in Table 3 and consistent with Hypothesis 3b, we find that significantly more auditors address the bias by choosing vouching (24 of 38, 63.2 percent) versus confirming (24 vs. 14, χ2 = 2.63, p = 0.05, one-tailed). Consistent with our theory, most auditors select vouching, the most common of substantive tests, as opposed to the more effective confirming. As previously noted, this finding is worrisome, because the diagnostic value of vouching is very low when the bias stems from the omission of management judgment inputs.

We examine a post-experimental question to verify that auditor test choice is consistent with our theory. The post-experimental question measures auditors' subjective perceptions about the quality of evidence provided by vouching versus confirming (the 21-point scale is anchored on “confirmation evidence is higher quality” and “confirmation evidence is lower quality”). We find that auditor perception of test quality is significantly related to their choice of vouching versus confirming when bias stems from externally prepared documents (p < 0.01, two-tailed) but not when bias stems from management judgment inputs (p = 0.26, two-tailed).18 These findings are consistent with our theory. When bias is from documents, we theorize that auditors will select an alternative test based on their individual preference, and perceived test quality should be an element of their preference. However, when bias is from management judgment inputs, we theorize that auditors will select an alternative test based on the availability heuristic, thereby overriding their individual preference.

Additional results

Because auditors are not routinely trained on biased processes, we theorize that a significant minority of auditors have systematic discrepancies in their beliefs about the normative use of biased evidence sources. Our results support this theory. We find that a significant minority of auditors select a biased evidence source after being told that it is biased. If this nonnormative selection is due to a lack of training, then a training intervention could improve auditor judgments in this domain. To test the potential effectiveness of a training intervention, we introduce a tutorial on bias after auditors have responded to our treatments, and then ask them to respond a second time to the treatment conditions.

The two-page tutorial first presents three categories of generic audit evidence: perfectly accurate, noisy, or biased. Next, the tutorial indicates the normative response when auditors encounter each type of evidence (respectively, no adjustment, increase sample size, acquire a new unbiased evidence source). Following the tutorial, auditors were asked which type of evidence was needed when auditing a biased process. Seventy-six (94 percent) of the auditors answered the question correctly.

We report our analysis of the 26 auditors (per Table 2) who judge increased sampling of the biased estimation process as sufficient after reading control deficiency documentation indicating that the estimation process is biased. As shown in Table 4, we find that 8 of 14 (57.1 percent) auditors changed their decision after completing the tutorial, in the absence of substantive test results from the biased estimation process. Conversely, none of 12 (0.0 percent) auditors changed their decision after completing the tutorial, in the presence of substantive test results from the biased estimation process. This difference in rate of change is significant (Fisher exact p < 0.01, two-tailed, Table 4).

We find that auditors receiving falsely favorable test results do not improve their decisions following the tutorial. This finding is consistent with the representativeness heuristic, because it appears that the falsely favorable test results made these auditors believe that the estimation process is effective. In the absence of the falsely favorable test results, our findings indicate that auditor judgment about the use of biased evidence sources can be improved with a relatively simple training intervention on the normative response to biased evidence. The recent emphasis on auditors' professional judgment has led firms to develop training interventions oriented to improving judgment (Ranzilla et al. 2011).19 Our findings suggest that training on the normative use of biased evidence sources would be helpful.

Robustness and other tests

Recognizing the insufficiency of increased sampling of the biased estimation process was the first step in our study. The second step involved selecting an alternative test to replace reviewing the biased estimation process. In supplemental tests (not tabulated) we find no evidence that judgments related to the sufficiency/insufficiency of increased sampling are associated with the choice of vouching or confirming audit procedures (p = 0.84, two-tailed).20 We also find no evidence that the absence or presence of substantive test results are associated with the choice of vouching or confirming audit procedures (p = 0.82, two-tailed). Overall, we do not observe carryover effects between the elements of our experiment.

On average, auditors in our study had a low rate of experience with percentage-of-completion accounting, the basis of our experimental task. To analyze the effect of experience, we compare the performance of auditors with higher and lower levels of percentage-of-completion accounting experience. We find that 65.3 percent (64.5 percent) of auditors who assessed their experience as lower (higher) judge that increasing sample size is insufficient, and we find that 44.9 percent (41.9 percent) of auditors who assessed their experience as lower (higher) choose the more appropriate procedure.21 For the auditors who assess their percentage-of-completion experience as very high, we find that 54.6 percent judge that increasing sample size is insufficient and 36.4 percent choose the more appropriate procedure.22 We observe no difference between performance of the highly experienced and less-experienced auditors on the sufficiency judgment (p = 1.00, two-tailed) or on test selection (p = 1.00, two-tailed). Variation in percentage-of-completion experience within our experiment does not influence our findings.

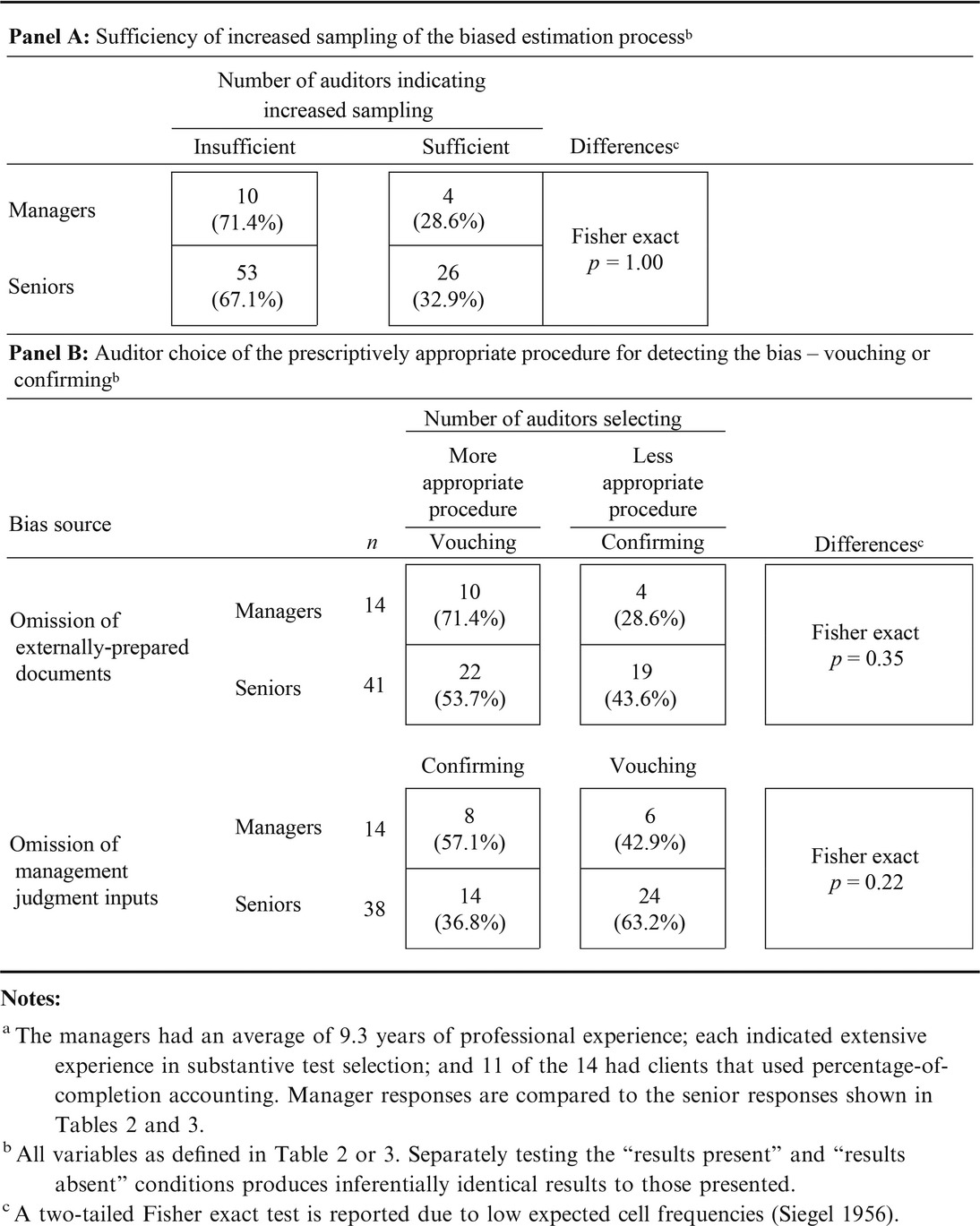

To further verify that our results are not driven by our participating auditors' relatively low experience with percentage-of-completion accounting, we conducted a second experiment with 14 managers from international audit firms. The managers had an average of 9.3 years of professional experience; each indicated extensive experience in substantive test selection, and 11 of the 14 had clients that used percentage-of-completion accounting. Each manager analyzed the sufficiency of increased sampling of the biased estimation process, and each manager selected tests to replace review of the biased process for bias stemming from both externally prepared documents and management judgment inputs.23

As shown in Table 5, we find that 10 (71.4 percent) of the managers judge that increasing sample size is insufficient. For bias from documents, 10 (71.4 percent) managers choose the effective and most efficient procedure, vouching, and four (28.6 percent) managers choose confirming. For bias from judgment inputs, eight (57.1 percent) managers choose the more effective procedure, confirming, and six (42.9 percent) managers choose vouching.24 We observe no difference between the performance of these managers and our sample of senior auditors in terms of the sufficiency judgment (p = 1.00, two-tailed) test selection when bias stems from externally prepared documents (p = 0.35, two-tailed), or test selection when bias stems from judgment inputs (p = 0.22, two-tailed). Due to the small sample of managers, our results comparing their responses to those of our senior auditor participants must be interpreted with caution. Regardless, results from our sample of managers indicate that a nontrivial proportion choose to increase sampling of a biased estimation process and select the less appropriate alternative test. Importantly, our additional findings from managers suggest that dealing with a biased evidence source causes difficulty for many auditors, regardless of experience.

5 Discussion

We find that a significant minority of senior auditors (33 percent) attempt to identify bias in an accounting estimate with increased sampling from the biased estimation process. Further, they do this after being told that the estimation process is biased. In supplemental tests, we find evidence that the observed results are not driven by lack of experience with percentage-of-completion accounting. We partition participants based on percentage-of-completion experience and find that those with high experience make judgments very similar to those with lower experience. In addition, we find that managers with significant task and test planning experience make judgments similar to the senior auditors. Our findings suggest that, regardless of experience, some auditors have flawed perceptions about evidence quality, precluding them from rejecting biased evidence sources (Soll 1999). Regarding tests that could identify the bias in the accounting estimate, we find that auditors often choose inefficient or ineffective tests. When the source of bias is externally prepared documents, about one-half of the auditors choose confirming instead of more efficient vouching. When the source of bias is management judgment, most auditors choose vouching instead of more effective confirming.

We discussed our findings with five audit partners experienced in percentage-of-completion accounting. Consistent with research indicating that audit supervisors are overconfident in their subordinates' competence, the partners expressed surprise that so many auditors judge that increased sampling of the biased estimation process is sufficient, given the case material's straightforward explanation of the bias (Han, Jamal, and Tan 2011; Kennedy and Peecher 1997). Several partners conjectured that increasing sample size is a common way to address control deficiencies and that some auditors routinely opt to do it without appropriately considering the situation.

The partners also indicated that the auditors' choices of alternative substantive tests are troubling, particularly when the bias stems from management judgment inputs, because most auditors chose to adjust the estimate using documents even though such a test is ineffective. They were surprised that auditors did not consistently revert to confirming in the face of any uncertainty, especially with the specter of PCAOB audit inspections. The partners admitted that mapping internal control deficiencies to substantive tests is difficult, particularly when the deficiency documentation offers no link to a substantive test, as in our bias from management judgment condition. Several suggested that if auditors fail to connect a deficiency's root cause to a substantive test, they will likely revert to what they know best (vouching), which is consistent with the availability heuristic. Finally, the partners indicated that managers should do better than seniors, but acknowledged that it is still difficult to get people to look beyond the familiar, regardless of experience. The interviews are consistent with our theoretical premises and offer practical insight into our results.

This research has limitations. Audit planning materials in practice are rich, but they are necessarily restricted in this study due to limits on access to the experimental participants. In addition, audits usually involve an audit team, and the ability to consult team members can affect audit judgments. In this experiment, we use individual judgments that do not capture dynamic team interactions. However, audit seniors' judgments and documentation can influence higher ranking members of the audit team (Hammersley, Johnstone, and Kadous 2011; Bellovary and Johnstone 2007; Ricchiute 1999). Firm partners that we interviewed indicated that seniors' judgments are important to the audit and that seniors are capable of addressing control deficiencies. Finally, our experimental setting of accounting estimates is complex, raising concerns about the experience level of our senior auditor participants. However, results from an additional sample of managers suggest lack of experience is not driving our findings.

With regard to practice, our findings inform the integrated audit. According to professional standards, auditors must integrate the internal control and financial statement audits (PCAOB 2007). Revised risk assessment standards were issued, in part, to improve the integration of controls into the financial statement audit (PCAOB 2010a). However, PCAOB inspections find that auditors sometimes do not appropriately change the nature, timing, and/or extent of their substantive tests in response to clients' internal controls (PCAOB 2008). Our findings are consistent with PCAOB concerns and shed light on potential sources of inefficient/ineffective auditor judgments surrounding the integration of control deficiencies and substantive test changes. The audit partners interviewed all indicated that auditor response to control deficiencies is an important issue. Several partners said that their firms struggle with integrating controls into the financial statement audit, and such integration is a common training topic, which adds credence to our findings about training the normative response to biased evidence sources.

Our study also contributes to theory. Specifically, our findings inform Griffith et al.'s (2013) field study on the audit of accounting estimates, helping explain why auditors do not “tend to generate independent estimates or consider what management has neglected to include in its estimation model” (Griffith et al. 2013, 4). We also find evidence of nonsampling risk when control deficiencies bias evidence used in substantive tests, supporting Peecher et al.'s (2007) contention that audit breakdowns often occur due to nonsampling risk/error. Overall, our findings provide a better understanding of how auditors perform when addressing errors of bias in management's estimation process.

Notes

Appendix A: Data collection scales

Dependent variables

All participants were provided the following description:

P1: Examine engineering cost analysis reports to test the reasonableness of estimated costs-to-complete (procedure in the initial audit plan shown on page 3).

P2: Obtain engineering cost analysis reports and vouch selected estimates of cost to complete to source documents from vendors and subcontractors. Reconcile with estimated cost to complete used for revenue recognition at December 31.

P3: Request positive confirmations from customers of the percent complete on contracts. Reconcile with estimated cost to complete used for revenue recognition at December 31.

The dependent variable for sufficiency of increasing sample size is:

Rate the likelihood that you will continue to select procedure P1 from the initial plan (i.e., increasing the sample size is a sufficient response) in your revised plan.

|

The dependent variable for alternative audit procedure choice is:

If you were to change from P1, rate the likelihood that you would select procedure P2 versus P3 to test estimated cost to complete in your revised plan.

|

Experimental Checks

- Had the audit team already completed the year-end substantive tests of revenue from contracts in progress based on the initial audit plan?

|

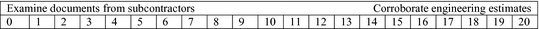

- The significant deficiency in contract cost-to-complete estimates involved the temporary engineer failing to:

|

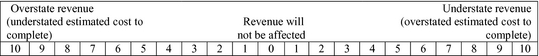

- The significant deficiency's effect on recognized revenue from contracts in progress would most likely be to:

|

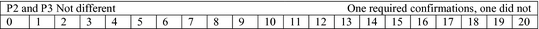

- What was different in the source of evidence in substantive procedures P2 and P3?

|

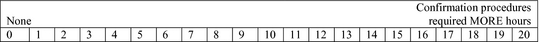

- What was the difference in the needed hours to complete between substantive procedures P2 and P3?

|