Advertising Expenditures on Media Vehicles and Sales*

*Accepted by Bruce McConomy and Leslie Berger. We thank Leslie Berger (editor-in-chief), Duane Kennedy, Bruce McConomy (associate editor), Jonathan Nash, an anonymous reviewer, and the participants at the 2020 CAAA Conference for their helpful comments. Sincere thanks to Steve Bull for his assistance with data collection. All errors belong to us. We declare that we have no relevant or material financial interests relating to the research described in this paper, and that this research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ABSTRACT

enThis research aims to advance the literature by identifying the association between four advertising media vehicles (Internet, press, outdoor, television) and contemporaneous sales. Previous research highlights the influence of advertising on firm value but does not delve into the effects of advertising media vehicles. Employing primary data, which detail the advertising expenditures of 88 publicly traded companies over 11 years, we empirically show a positive association between television and outdoor advertising expenditures and contemporaneous sales. However, we do not find any significant results for press and Internet advertising. We investigate the moderating effect of the growth opportunities, industry sectors, and firm size. Our study offers important evidence that the contemporaneous relationship between sales and advertising expenditures varies by media vehicle. We discuss the implications of our findings for the matching principle, a principal concept in accrual accounting.

RÉSUMÉ

frDépenses publicitaires liées aux véhicules médiatiques et ventes

La présente étude vise à enrichir la littérature en faisant ressortir la relation entre quatre véhicules médiatiques utilisés pour la publicité (Internet, presse, affichage extérieur, télévision) et les ventes qui y sont associées. La recherche antérieure fait état de l'influence de la publicité sur la valeur des entreprises, sans toutefois s'attarder aux effets des médias utilisés aux fins publicitaires. À l'aide de données primaires qui présentent en détail les dépenses publicitaires de 88 entreprises cotées en bourse sur une période de 11 ans, nous établissons de façon empirique une relation positive entre les dépenses pour la publicité à la télévision et sur des affiches à l'extérieur, et les ventes qui y sont associées. Toutefois, nous ne trouvons aucun résultat probant concernant la publicité dans la presse ou sur Internet. Nous examinons l'effet modérateur associé aux possibilités de croissance, aux secteurs d'activités et à la taille des entreprises. Notre étude fournit d'importantes données probantes indiquant que la relation contemporaine entre les ventes et les dépenses publicitaires varie en fonction du média utilisé. Nous discutons des conséquences de nos résultats pour le principe du rapprochement des produits et des charges, un concept de base de la comptabilité d'exercice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Firms incur expenditures that have the potential to create future value. Examples of these expenditures include those on R&D, selling, general, and administrative activities (SG&A), human capital, and marketing activities. R&D activities create innovation (Kelm et al. 1995), investing in employee growth and the workplace environment have firm value benefits (Mao and Weathers 2019), SG&A create future value (Banker et al. 2011), and marketing strategies build brand awareness (Rao et al. 2004). These expenditures create current and future benefits for a firm, so in a sense they belong to the more general category of long-term corporate investments that create future value. However, they are different than tangible investments because tangible investments are depreciated over their entire lives, while these expenditures are fully expensed in the period they are incurred (with some exceptions for R&D).

The value-creation nature of these expenditures creates complications for the matching principle in accrual accounting. If the value created by these expenditures is observed in future periods, the matching between expenses and contemporaneous revenues will be poor, and there will be noise over economic benefits observed in the current period. The matching principle is one of the fundamental concepts in accounting. However, there are relatively few accounting studies examining how the contemporaneous relationship between revenues and expenses works. Advertising expenditures create a unique setting to study this association. In this paper, we study the role of advertising media vehicles (i.e., TV, Internet, press, outdoor) in explaining the matching between revenues and advertising expenditures.

Many scholars in marketing, management, and related fields share the goal of trying to explain the benefits of advertising for firms. Previous studies reveal that advertising expenditures have a positive impact on a firm's perceived brand equity (Aaker and Jacobson 1994; Rao et al. 2004). Among them, Aaker and Jacobson (1994) suggest that advertising expenditures generate future cash flows and enhance shareholder value by creating brand loyalty and brand association. Further, marketing studies emphasize the role of various media vehicles in influencing the cognition, affect, and experience of customers differently (Jeong and Hwang 2016).

On the other hand, when evaluating the success of advertising, accounting research focuses on output-based performance measures. Constructs such as brand loyalty and brand awareness are not observable in financial statements, nor are intermediate effects such as cognition and affect (Gupta and Zeithaml 2006). For financial reporting purposes, the choice is simple: the influence of advertising needs to be observable in metrics such as sales, earnings, stock returns, and so forth (Thompson et al. 1991). Therefore, accounting simplifies the framework that allows advertising expenditures to create value and dismisses the intermediate effects.

This study tests whether advertising expenditures categorized by media vehicles have different impacts on contemporaneous sales performance. Our perspective is that of stakeholders, who only have access to financial statements,1 and we aim to document to what extent advertising expenditures categorized by media vehicles are matched with contemporaneous revenues. We ask whether having more granular information about advertising transactions on financial statements would alter our understanding of their value-creation potential, as well as the matching principle implemented in accrual accounting.

First, we show that total advertising expenditure is positively associated with contemporaneous sales, after controlling for macroeconomic factors (i.e., Consumer Price Index, private consumption growth) and firm characteristics (i.e., firm size, cash ratio, and debt ratio). This is consistent with the past literature (Torres and Gelb 2002; Turner 2000). However, its impact heavily depends on which media vehicle the firm is using. We find significant positive associations between sales and advertising expenditures on TV and outdoor. On the other hand, we do not find any significant associations between sales and advertising expenditures on Internet and press.

Last, we split our sample based on growth opportunities, proxied by the book-to-market ratio, industry sectors, and firm size. Our results suggest that firms, regardless of the specification, benefit from using TV as an advertising media vehicle, and the economic benefits can be observed in the current sales performance. However, the (potential) benefits and costs of expenditures on all other media vehicles largely depend on the growth opportunities, industry sectors, and firm size.

Finally, we run a variety of sensitivity analyses and show that our results remain similar even when we use lagged independent variables and eliminate firm-quarter observations with zero advertising variables.

Firms spend massively on advertising, but there is uncertainty about how best to allocate their advertising budget among the various media vehicles and how spending across various vehicles will impact demand. Our study highlights the unexplored gap regarding the impact of advertising media vehicles on firm sales, represents an important theoretical contribution, and holds practical significance for managers, retailers, public policymakers, and investors. These results are crucial in understanding how information in advertising spending manifests itself in the financial markets.

We embrace the disaggregate nature of advertising spending in the new media era. While the advertising market is continuously growing, the composition of advertising spending is changing dramatically, and it is growing more critical to understand how the market responds to media vehicles. Therefore, our findings may help in the allocation of advertising resources by documenting the market's response to advertising across various media vehicles. Unlike prior studies that are limited to shorter time periods, one industry, and other restrictions in their methodology, this study is among the first to explore the relevance of advertising media vehicles using firm-level panel data.

The findings may also be helpful in devising more successful advertising strategies and be of interest to managers. Running an effective advertising strategy is becoming increasingly more difficult in this era of multiple media vehicles. This raises the question: Is multitasking detrimental for advertisers? This study suggests that advertising media vehicles can be instrumental in carrying out firms' sales strategies and generating economic gains. However, it is also plausible that a media vehicle's effectiveness is overshadowed by the usage of other media vehicles. Thus, managers need to be wary of the potential advantages and limitations of media vehicles in terms of their effects on the firm value.

Last, our results do not readily lend themselves to be adequately addressed based on a priori theorizing. We argue that accounting theory has not sufficiently addressed how advertising expenditures are matched with contemporaneous revenues and the role of disclosure in this association. We believe our findings reveal potentially important relationships that can expand our understanding of the matching principle.

Section 2 discusses the background information. Section 3 describes the sample characteristics. Section 4 presents the empirical analyses. Section 5 discusses the implications of our findings for future research. Finally, section 6 presents our concluding remarks.

2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Literature Review

Our study is part of the literature that focuses on the association between advertising expenditures and outcome-based measures, such as earnings and cash flows. Various studies across the disciplines of marketing, accounting, and finance suggest that advertising spending can, directly and indirectly, affect sales, firm value, and market participants (Madsen and Niessner 2019; Srinivasan and Hanssens 2009). Research focusing on advertising primarily employs two approaches.

The first stream of research focuses on the ways that advertising influences consumer behavior from a psychological perspective. Specifically, these studies examine how advertising triggers cognition or affect to change consumers' behavioral actions (e.g., make purchases). The basic premise that advertising influences consumer behavior from a psychological perspective has general implications, such as greater market awareness, quality competitiveness, customer preference, and brand image (Koslow et al. 2006; Kulkarni et al. 2003; Tellis 2009). These benefits induced by advertising, in turn, boost the future sales and profits of the firm (Kirmani and Wright 1989; Leone 1995; Mela et al. 1997; Osinga et al. 2010). Further, Srinivasan and Hanssens (2009) suggest a link between advertising and instant awareness of new products, which would imply that firm advertising leads to more and faster cash flows.

The second stream of research focuses on the economic gains of advertising expenditures created by consumers. The focus of this stream is outcome-based accounting performance measures, such as sales. These studies collect observable constructs from annual reports, financial statements, or private data sets. The underlying assumption is that advertising produces immediate shifts in consumer purchase and product selection (Wang et al. 2009). These immediate shifts have a significant impact on measures of firm performance such as sales volume (Givon and Horsky 1990; Joshi and Hanssens 2010) and market share (Wang et al. 2009).

Studies in this second research stream find that advertising helps smooth out the variability in seasonal demand and reduces consumer risks with safer cash flows. Byzalov and Shachar (2004) note that advertising can help consumers to deal with risk aversion. Also, advertising can create a barrier to competition, provide bargaining power vis-à-vis suppliers, and achieve “greater dynamic efficiency and flexibility in adapting environmental changes than its competitors” (McAlister et al. 2007).

Chemmanur and Yan (2009) argue that advertising can signal quality to the product market and stock market investors on the true value of a firm's projects, thus allowing them to price the firm's equity correctly in equilibrium. Boyd and Schonfeld (1977) point out a positive impact of advertising on stock prices because the purchase of products and stocks is similar: individuals who respond to advertising messages in a product setting also respond to advertising messages in a financial setting. That is, investors may pick stocks based on their familiarity with the stocks. Indeed, investors often prefer firms that have higher brand visibility induced by advertising (Fehle et al. 2005). Further, advertising enables firms to enjoy more information channels to communicate with investors and obtain greater ownership breadth and investor attention (Grullon et al. 2004). Advertising reduces investors' search costs and signals firm-specific competitiveness regarding its existing products and new projects. Chauvin and Hirschey (1993, 128) conclude that “spending on advertising is a form of investment in intangible assets with predictably positive effects on the size and variability of future cash flows.”

As discussed above, prior studies look at the association between advertising spending and firm value by either examining how advertising triggers the cognition of consumers or focusing on immediate shifts in outcome-based accounting performance measures due to advertising. However, prior research focuses less on an important feature of advertising spending that sets this type of expenditure type apart from others. Advertising reaches consumers through media vehicles. Simple intuition indicates that different media vehicles bring different firm benefits. If they were all the same and the choice to use one vehicle over another was trivial, there would not be spending variations across these vehicles. Simply put, a firm would spend its entire advertising budget on one vehicle without any regard for other options. This is not the practice. For instance, a viewer of a commercial TV broadcast encounters frequent advertisements, and advertisements are also prominent in magazines, newspapers, and radio broadcasts. A firm is willing to pay only so much for a message, and its willingness to pay is driven by the number of potential consumers that the message might reach and changes in performance measures. No other expenditure type can be further categorized using clear boundaries.

While limited, there are some studies examining various advertising media vehicles independently. Prior research shows that television advertising affects a firm's profitability (Danaher and Dagger 2013; Notta and Oustapassidis 2001; Pedrick and Zufryden 1991). Studies investigating exposure through television shows about product development find a positive relationship between these shows and positive stock returns through enhanced attention (Takeda and Yamazaki 2006). The influence of online information on firm performance reveals that online media have a strong relationship with firm performance. Among new vehicles of advertising, emails and sponsored search influence sales and profits most, but others, such as online display advertising and social media, do not have significant associations (Danaher and Dagger 2013). These studies only focus on one type of media vehicle and exclude a firm's spending on other vehicles. The findings are important to argue the importance of various vehicles, but they do not paint a full picture. Our paper focuses on understanding the association between advertising expenditures categorized by media vehicles and sales. We discuss our motivation for our research question in the following section.

Motivation

In accrual accounting, the revenue recognition principle states that revenues should be recorded during the period they are earned, regardless of when the transfer of cash occurs. In addition, the matching principle instructs that an expense should be reported in the same period in which the corresponding revenue is earned, and is associated with accrual accounting. By recognizing costs in the period they are incurred, a business can see how much money was spent to generate revenue, reducing noise from the timing mismatch between when costs are incurred and when revenue is realized.

The topic of matching has a long history in accounting. Accounting earnings are shaped by both economic factors and the degree of matching success. However, matching considerations are absent for advertising because such advertising expenditures are expenses as they are incurred. IAS 38 (IFRS Foundation 2017) requires firms to write off all expenditures in the current period. Consequently, firms record all the expenditure on advertising in the current period when profit levels are known with more certainty, rather than risking carrying these costs over into future periods as capitalized costs. The accounting practice to charge advertising expenditure to current expenses produces an implicit amortization rate of 100%.

Another important reason for the lack of matching considerations for advertising is the lack of disclosure on the financial statements. Advertising expenditures are disclosed voluntarily. In most cases, these expenditures are bundled with SG&A expenses, and firms rarely report advertising expenditures separately. Further, firms never report how their advertising spending is allocated among various media vehicles in their quarterly or annual reports.

A marketing set which describes advertising spending on every medium (i.e., TV, Internet, press, outdoor) will generate a given level of revenue output. With perfect matching, all relevant expenses should be matched against the associated contemporaneous revenue. Because advertising is presumed to generate revenue, perfect matching should lead to a significant positive association between advertising expenditures and sales.

On the other hand, if there is poor matching and noise over economic benefits gained, we would find either insignificant or negative associations. Poor matching is the extent to which expenses are not matched against the resulting revenues and is modeled as noise in the economic relation of advancing expenses to earn revenues. Poor matching can arise for several reasons, such as fixed costs, poor traceability of costs, and accounting rules.

We would argue that an insignificant association suggests poor traceability of costs, while a negative association between advertising spending and sales is an indication of advertising spending behaving like fixed costs. In other words, once an optimal level of advertising spending is reached, any additional advertising spending per unit will be associated with a decrease in sales.

If advertising expenditures and contemporaneous sales are properly matched, we predict finding a positive association. On the other hand, if they are imperfectly matched, we predict finding an insignificant or a negative association.

3 SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS

Data

We obtain monthly advertising information from a proprietary database constructed by CreativeClub, a media-tracking company. Our sample covers 2004 through 2014 (data availability).2 The data are gathered by continuously monitoring multiple media vehicles and collecting information about observed advertisements. The media vehicles covered include (i) television (cable, network, and cinema),3 (ii) the Internet, (iii) press (newspapers, local magazines, consumer magazines, and business magazines), and (iv) outdoor (e.g., billboards, displays).4 CreativeClub is a UK-based advertising database run by Ebiquity (formerly known as Thomson Intermedia), which is a provider of independent marketing analytics. Our initial sample from CreativeClub includes 180 unique firms, which translates into 7,920 quarterly observations.

The translation of media spots into monetary amounts is done by surveying media vehicles for their rates at various points during the quarter. For example, for television, the rates used to estimate advertising expenditures are supplied primarily by the networks and, in some instances, by advertising agencies and advertisers. The database covers all media spending that appears in the tracked vehicles and is reported by brand. For example, the media spending by Unilever is reported separately by its brands, which include Knorr, Dove, and many others. We aggregate the advertising outlays of all brands that belong to a particular firm. We emphasize that our data cover only media spending and does not include other forms of advertising, such as the production costs of advertising and promotional materials.

Creative Club covers a select number of companies that are operating in the United Kingdom. They cover various media vehicles (e.g., TV, Internet) and the ads published in them. Later, they assign these to a company. A significant portion of their coverage includes private companies. Because we cannot control for firms' internal decision making on their marketing budget, we focus on firms for which running ads is a creative choice rather than a budgetary decision. To operationalize this choice, we make a broad assumption that firms with high market values have the financial means to use every media vehicle, should they choose to. To make sure that the choice of running ads is a creative rather than a budgetary decision and that firms in this study's sample can afford to run ads, we only include firms that have been a constituent of the Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) 100 Index at least once during the sample period.5 We acknowledge that the data acquired with CreativeClub presents its unique limitations, since our sample selection heavily relies on what they are offering. Notwithstanding this limitation, we still believe the data on advertising expenditures to offer unique insights that can be used by regulators and researchers in other research questions.

Next, we collect the data on firm performance and other firm characteristics from the quarterly Compustat Global database.6 To ensure that firms in our sample do not drop out unexpectedly, we require each firm in our sample to be available for at least two consecutive years. We note that we do not always have the necessary quarterly data on Compustat Global. Our final sample covers 88 publicly listed firms in the United Kingdom and a total of 2,039 firm-quarter observations for the time period from 2004 to 2014. All monetary variables are denoted in British pounds.

Table 1 reports the detailed distribution of our sample based on year and 2-digit Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) industries. Except for the year 2004, more than 50% of our sample is represented in each year. Beyond the year 2008, more than 80% of our sample is included in each year. Firms in the consumer discretionary and consumer staples sectors are most widely represented in the sample. On the other hand, firms in the information technology and materials sectors are the least represented sectors. Our sample does not include any firms in the real estate and financial sectors.

| Year | Obs. | Number of unique firms | GICS industries | Sector name | Obs. | Number of unique firms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 114 | 41 | 10 | Energy | 58 | 2 |

| 2005 | 166 | 63 | 15 | Materials | 12 | 1 |

| 2006 | 138 | 67 | 20 | Industrials | 304 | 13 |

| 2007 | 82 | 53 | 25 | Consumer Discretionary | 735 | 31 |

| 2008 | 240 | 73 | 30 | Consumer Staples | 414 | 19 |

| 2009 | 245 | 72 | 35 | Health Care | 124 | 4 |

| 2010 | 261 | 77 | 45 | Information Technology | 29 | 1 |

| 2011 | 218 | 78 | 50 | Communication Services | 303 | 15 |

| 2012 | 109 | 78 | 55 | Utilities | 60 | 2 |

| 2013 | 168 | 83 | ||||

| 2014 | 298 | 85 | ||||

| Total | 2,039 | Total | 2,039 | 88 |

- Notes: This table reports the number of quarter-year observations and unique firms included in this study's sample. We report sample distribution by year and industry sectors, defined by the GICS.

Approximately 60% of the unique firms in our sample use at least one of the four advertising media vehicles. When a firm does not report expenditures on one of the media vehicles, we assign zero for that variable. Since we include firms that are part of the FTSE 100 Index, we assume that not using every media vehicle is not a budgetary decision.

Variables

We define the dependent variable as sales of firm i, quarter (t), scaled by total assets, denoted as  . The primary interest variables are advertising expenditures on four different media vehicles. We include (i)

. The primary interest variables are advertising expenditures on four different media vehicles. We include (i)  , measured as TV and cinema advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t;7 (ii)

, measured as TV and cinema advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t;7 (ii)  , measured as Internet advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t; (iii)

, measured as Internet advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t; (iii)  , measured as press advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t; and (iv)

, measured as press advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t; and (iv)  , measured as outdoor advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t. Each advertising variable is scaled by total assets.

, measured as outdoor advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t. Each advertising variable is scaled by total assets.

We include  , measured as private consumption growth, which measures the growth in private consumption in the United Kingdom while adjusting for inflation, in quarter t. Private consumption represents the total monetary value of consumer purchases of goods and services. It includes all purchases made by consumers, such as food, housing (rents), energy, clothing, health, leisure, education, communication, transport, and hotels and restaurant services. It also includes durable goods (such as cars), but not households' purchases of dwellings, which are counted as household investments. We also include

, measured as private consumption growth, which measures the growth in private consumption in the United Kingdom while adjusting for inflation, in quarter t. Private consumption represents the total monetary value of consumer purchases of goods and services. It includes all purchases made by consumers, such as food, housing (rents), energy, clothing, health, leisure, education, communication, transport, and hotels and restaurant services. It also includes durable goods (such as cars), but not households' purchases of dwellings, which are counted as household investments. We also include  , measured as the Consumer Price Index, which is a price index that measures the average cost of goods and services purchased by the typical household in the United Kingdom, in quarter t.

, measured as the Consumer Price Index, which is a price index that measures the average cost of goods and services purchased by the typical household in the United Kingdom, in quarter t.

Our study includes firm size (denoted as SIZE), calculated as the natural logarithm of a firm's total employees, debt ratio (denoted as DEBT_RATIO), calculated as total short-term and long-term debt as a percentage of total assets, and cash ratio (denoted as CASH_RATIO), calculated as the total cash balance as a percentage of current liabilities. Last, our study includes the book-to-market ratio, BTM.

4 EMPIRICAL ANALYSES

Univariate Analyses

Table 2 reports summary statistics for our sample firms. The sales to total assets ratio, on average, is 23%, with a median of 20%. Firm size, which is the natural logarithm of total employees, has a mean of 9.34 and a median of 9.51. The average book-to-market ratio of firms in our sample is 0.73, with a median of 0.55, which is comparable to the sample used in Cohen and Zarowin (2010). The average debt ratio is 62%, while the average cash ratio is 43%.

| Mean | SD | Q1 | Median | Q3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL_ADV | 0.0017 | 0.0061 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0010 |

| TV | 0.0011 | 0.0053 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 |

| INTERNET | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| PRESS | 0.0004 | 0.0011 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 |

| OUTDOOR | 0.0002 | 0.0010 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| PCG | 0.0025 | 0.0080 | −0.0031 | 0.0046 | 0.0094 |

| CPI | 0.0262 | 0.0111 | 0.0181 | 0.0249 | 0.0325 |

| SIZE | 9.3389 | 2.3200 | 7.7524 | 9.5086 | 10.6803 |

| DEBT_RATIO | 0.6188 | 0.1859 | 0.5154 | 0.6234 | 0.7458 |

| CASH_RATIO | 0.4332 | 0.5510 | 0.1514 | 0.2626 | 0.4784 |

| SALES | 0.2313 | 0.1322 | 0.1388 | 0.1985 | 0.3008 |

| BTM | 0.7318 | 0.6949 | 0.3052 | 0.5450 | 0.9265 |

| Obs. | 2,039 | ||||

- Notes: This table reports descriptive statistics of this study's variables. All variables are defined in Appendix 2.

On average, total advertising expenses constitute 0.17% of total assets. Advertising expenditures on TV, Internet, press, and outdoor are about 0.11%, 0.01%, 0.04%, and 0.02% of total assets, respectively. Advertising expenditures on TV constitute about 42% of a firm's total advertising expenditures. Advertising expenditures on press and outdoor each constitute more than 20% of total advertising expenditures.

Table 3 presents Pearson's (lower part of the diagonal) and Spearman's (top part of the diagonal) correlation matrix with pairwise correlations between our variables. We do not see any problems with strong collinearity among our explanatory variables used in our empirical models. In addition, the variance inflation factors in our subsequent econometric models range from 2.1 to 8.15 per variable; these are well within the acceptable ranges (under 10), eliminating concerns over multicollinearity.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) TV | 1.0000 | −0.1109 | 0.1773 | 0.7015 | −0.0951 | −0.1421 | −0.0947 | −0.1490 | 0.2428 |

| (2) INTERNET | 0.1118 | 1.0000 | 0.1407 | 0.0205 | 0.0852 | 0.0458 | 0.1859 | 0.2299 | 0.0226 |

| (3) PRESS | 0.1381 | 0.3678 | 1.0000 | 0.1819 | −0.3094 | −0.0212 | 0.0150 | 0.0037 | 0.2213 |

| (4) OUTDOOR | 0.3733 | 0.2013 | 0.3269 | 1.0000 | 0.0772 | −0.1111 | 0.0185 | −0.0995 | 0.0781 |

| (5) SIZE | −0.2591 | −0.1686 | −0.3724 | −0.2182 | 1.0000 | −0.1296 | 0.0992 | 0.4554 | −0.3731 |

| (6) DEBT_RATIO | −0.1006 | −0.1438 | −0.0979 | −0.1259 | −0.1809 | 1.0000 | −0.2631 | −0.1433 | 0.0803 |

| (7) CASH_RATIO | −0.0255 | 0.1173 | 0.0658 | 0.0192 | −0.0247 | −0.3576 | 1.0000 | −0.0139 | −0.2667 |

| (8) BTM | −0.0886 | −0.0424 | −0.0837 | −0.0845 | 0.3437 | −0.0660 | −0.0574 | 1.0000 | −0.1803 |

| (9) SALES | 0.3350 | 0.0037 | 0.1408 | 0.1874 | −0.3835 | 0.1465 | −0.2346 | −0.1875 | 1.0000 |

- Notes: This table presents Pearson's (lower part of the diagonal) and Spearman's (top part of the diagonal) correlation matrix with pairwise correlations between this study's variables. All variables are defined in Appendix 2.

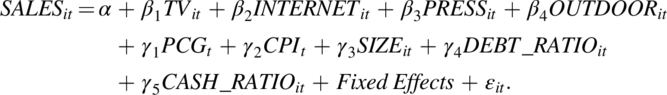

Advertising Expenditures and Sales

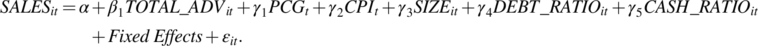

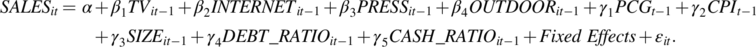

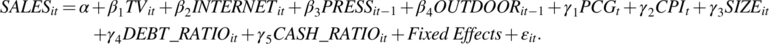

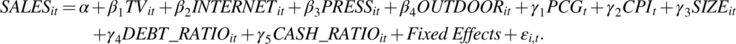

(1)

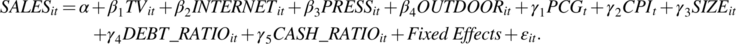

(1) , which is sales of firm i, in quarter (t), scaled by total assets. Advertising expenditures are aggregated over a quarter. The primary interest variables are advertising expenditures on four different media vehicles. We include

, which is sales of firm i, in quarter (t), scaled by total assets. Advertising expenditures are aggregated over a quarter. The primary interest variables are advertising expenditures on four different media vehicles. We include  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , representing the advertising expenditures on TV, Internet, press, and outdoor media vehicles of firm i, quarter (t), scaled by total assets.

, representing the advertising expenditures on TV, Internet, press, and outdoor media vehicles of firm i, quarter (t), scaled by total assets.To control for macroeconomic factors that might influence a firm's sales performance, we include private consumption growth,  , and the Consumer Price Index,

, and the Consumer Price Index,  in the United Kingdom.

in the United Kingdom.

Next, we include control variables to control firm characteristics that might drive sales. First, we include firm size, SIZE. While small firms often have behavioral advantages, in many activities they are at a disadvantage with respect to sales and costs. Sales and costs have effects of scale, scope, experience, and learning. Small firms generally produce small volumes (scale) of few products (scope). They have not been in business long and thereby have little benefit from economies of experience. They have limited capacity for the acquisition of knowledge (learning). Therefore, firm size plays a role in predicting a firm's sales performance, since firm size will influence scale, scope, experience, and learning within a firm's operations.

Last, we include DEBT_RATIO and CASH_RATIO. A firm's debt ratio may explain aggressive sales efforts, while the cash ratio would capture whether a firm is offering sales on account. Accrual-based accounting recognizes revenues when earned, regardless of when cash is received. Since the firms in our sample are large firms, we expect cash collection to be less than timely; therefore, we predict a negative association between sales and cash ratio. All of the variables are defined in detail in section 3.

In the model,  captures the random error term. Our model includes industry and time fixed effects to control for other unobserved industry-specific and time-specific heterogeneity and to lessen remaining heteroskedasticity concerns. The identifying assumption for this model is that fixed effects pick up time-invariant sources of unobserved heterogeneity, which might induce an endogeneity bias, and that such a specification again places less burden on the control function approach because it serves only to condition out the time-varying sources of unobserved variation that correlate with the error term. To account for potential dependence among observations, all our statistical tests are based on clustered standard errors at the firm level (Petersen 2009).

captures the random error term. Our model includes industry and time fixed effects to control for other unobserved industry-specific and time-specific heterogeneity and to lessen remaining heteroskedasticity concerns. The identifying assumption for this model is that fixed effects pick up time-invariant sources of unobserved heterogeneity, which might induce an endogeneity bias, and that such a specification again places less burden on the control function approach because it serves only to condition out the time-varying sources of unobserved variation that correlate with the error term. To account for potential dependence among observations, all our statistical tests are based on clustered standard errors at the firm level (Petersen 2009).

Our focus in this study is the contemporaneous relationship between sales and advertising expenditures. Clearly, studying a contemporaneous phenomenon is an empirical issue. Our study's goal is not to capture brand awareness or other brand components. We examine the economic gains of advertising expenditures in the short term. There are two reasons why we focus on the contemporaneous relationship.

First, our primary goal is to capture revenue and advertising expenditure matching. Under IFRS, the current accounting treatment for advertising costs is to expense them immediately. The rationale behind this is that advertising, which is designed to elicit immediate sales, is to be expensed as incurred or when the advertisement first appears. Advertising that can be expected to result in benefits in future periods should be capitalized as an intangible asset, as long as the benefits are measurable and a company makes certain disclosures. The immediate expensing procedure has been followed by most companies for decades. Therefore, from an accounting perspective, the benefits resulting from the association between advertising costs and sales is assumed to be observed in the short term.

Second, on the basis of studies using data for shorter periods, Clarke concludes that “the duration of cumulative advertising effect on sales is between 3 and 15 months; thus this effect is a short-term (about a year or less) phenomenon” (1976). Several studies offer further support for this conclusion. Ashley et al. (1980), Boyd and Seldon (1990), and Seldon and Doroodian (1989) all offer evidence that the effect of advertising on sales is largely depreciated within a year (if not less). Further, Leone (1995) presents empirical support for the generalization that, on average, the effect of advertising on sales is largely depreciated within six to nine months. While there is consensus that the impact of advertising on sales is short-term, there is no consensus on when it disappears. We take a conservative approach and assume that the impact of advertising on sales dissipates in three months.

Table 4 presents multivariate evidence regarding the impact of total advertising expenditures on sales. Table 5 uses advertising expenditures on each media vehicle as the primary interest variables. In each table, to ease the interpretation of the coefficients, the first column presents standardized estimates. Therefore, each coefficient in the table describes the impact of a one standard deviation increase in the independent variable on sales. The second column reports the t-statistics.

| Standardized estimates | t-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.0000 | 2.135** |

| TOTAL_ADVt | 0.2891 | 5.0101*** |

| PCGt | 0.0460 | 2.2405** |

| CPIt | 0.0214 | 1.6501* |

| SIZEt | −0.2401 | −1.741* |

| DEBT_RATIOt | 0.1269 | 1.701* |

| CASH_RATIOt | −0.1684 | −3.399*** |

| Obs. | 2,039 | |

| Adj. R2 | 57.86% | |

| Year FE | Yes | |

| Quarter FE | Yes | |

| Industry FE | Yes | |

| St. error clustering | Firm |

- Notes: This table reports coefficient estimates of the following OLS specification: The model includes industry, quarter, and year fixed effects. The sample period covers 2004–2014. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively. See Appendix 2 for variable definitions.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized estimates | t-value | Standardized estimates | t-value | Standardized estimates | t-value | Standardized estimates | t-value | Standardized estimates | t-value | |

| Intercept | 0.0000 | 2.123** | 0.0000 | 2.388** | 0.0000 | 2.551** | 0.0000 | 2.534** | 0.0000 | 2.526** |

| TVt | 0.2242 | 3.981*** | 0.2657 | 3.923*** | ||||||

| INTERNETt | −0.0119 | −0.333 | 0.0303 | 0.850 | ||||||

| PRESSt | −0.0242 | −0.418 | 0.0249 | 0.442 | ||||||

| OUTDOORt | 0.1627 | 3.493*** | 0.2087 | 4.190*** | ||||||

| PCGt | 0.0459 | 2.228** | 0.0467 | 2.321** | 0.0411 | 2.073** | 0.0417 | 2.091** | 0.0413 | 2.041** |

| CPIt | 0.0232 | 1.833* | 0.0218 | 1.711* | 0.0165 | 1.267 | 0.0172 | 1.279 | 0.0193 | 1.399 |

| SIZEt | −0.2426 | −1.710* | −0.2746 | −1.961** | −0.3559 | −2.185** | −0.3554 | −2.108** | −0.2898 | −2.037** |

| DEBT_RATIOt | 0.1374 | 1.973** | 0.1110 | 1.432 | 0.0595 | 0.627 | 0.0571 | 0.614 | 0.1055 | 1.410 |

| CASH_RATIOt | −0.1599 | −3.388*** | −0.1654 | −3.204*** | −0.2044 | −3.261*** | −0.2027 | −3.204*** | −0.1904 | −3.670*** |

| Obs. | 2,039 | 2,039 | 2,039 | 2,039 | 2,039 | |||||

| Adj. R2 | 58.98% | 57.17% | 51.56% | 51.52% | 55.14% | |||||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Quarter FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| St. error clustering | Firm | Firm | Firm | Firm | Firm | |||||

- Notes: This table reports coefficient estimates of the following OLS specification: *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively. Each model includes industry, quarter, and year fixed effects. The sample period covers 2004–2014. See Appendix 2 for variable definitions.

Table 4 reveals that total advertising expenditures are positively associated with sales and significant at a 1% level. This is consistent with the literature that there is a positive association between sales and total advertising expenditures. Further, the positive sign indicates that the economic benefit of advertising is captured in the current sales performance.

In Table 5, we investigate the impact of each media outlet on sales. This model considers the possibility that the association between sales and advertising expenditures varies by the media vehicle. Table 5 presents five models. Model (1) includes all media vehicles (i.e., TV, INTERNET PRESS, OUTDOOR). Models (2) to (5) include each advertising media vehicle variable individually to see whether our results are driven by multicollinearity.

As discussed in section 2, we expect to find positive associations if there is proper matching between contemporaneous sales and advertising expenditures. On the other hand, we expect to find insignificant or negative associations if there is any evidence of imperfect matching between advertising expenditures and sales. Model (1) reveals that advertising expenditures on TV and outdoor are positively associated with sales, significant at 1%. On the other hand, advertising expenditures on Internet and press are both insignificant in our model.

Our results suggest that economic benefits gained from TV and outdoor advertising expenditures are observed in the current sales performance of a firm. However, current sales do not reflect the benefits gained by press and Internet advertising expenditures. The lack of results for press and Internet advertising expenditures does not necessarily suggest a lack of economic benefits for these media vehicles, as the economic benefits may be observed in the future. However, our results imply that the one-size fit matching principle may not be appropriate for advertising expenditures when different media vehicles are used. Models (2) to (5) reveal results consistent with our main model.

The coefficients of the control variables in Tables 4 and 5 are consistent with each other. As expected, changes in macroeconomic factors explain some of the variation in sales performance. We find PCG and CPI to be positively associated with sales, significant at a 5% level. We find the coefficient on SIZE to be significantly negative in both models. These results contradict our prediction that larger firms are likely to have more economies of experience, which can be used to enhance sales growth. In contrast, our results support the idea that smaller firms can react more quickly because they are less burdened by bureaucracy and have more freedom to enhance sales growth (Uhlaner et al. 2013). Finally, we report insignificant coefficients on DEBT_RATIO, and significantly negative coefficients on CASH_RATIO.

Growth Opportunities

One plausible interpretation for the positive association between advertising expenditures and sales is that the economic benefit of advertising is observed in the current sales performance, suggesting proper matching between revenues and expenses. On the other hand, a lack of results would imply that either advertising is an intangible asset for which benefits will be collected in the future or there are cost inefficiencies within the firm and there will be no economic benefits. In this section, we explore the conditions under which the associations we find are stronger or weaker.

If advertising activities create economic benefits in the current period, then the power of this association should vary when firms have more incentives to exhibit an aggressive sales effort. We investigate this issue by conditioning our analysis on the median book-to-market ratio. We use the book-to-market ratio as a proxy for growth opportunities at stake. A low book-to-market ratio indicates growth opportunities, suggesting that firms will have incentives for aggressive sales efforts. We split our sample into two based on whether a firm's book-to-market ratio is above the sample median for the quarter.

Table 6 shows the results of this analysis. Model (1) shows the results when a firm's book-to-market ratio is above the sample median for the quarter, while model (2) shows the results when the ratio is below the sample median for the quarter. Both models reveal that the coefficients on TV and outdoor advertising are significantly positive. These results are consistent with our main findings. In model (1) of Table 6, when the book-to-market ratio is above the median, we find that the coefficient on press advertising is positive, significant at a 10% level. On the other hand, in model (2), when the book-to-market ratio is below the median, the coefficient on press advertising is negative, significant at 5%. We do not find results for Internet advertising.

| Model (1) > median (BTM) | Model (2) < median (BTM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized estimates | t-value | Standardized estimates | t-value | |

| Intercept | 0.0000 | 1.378 | 0.0000 | 3.533*** |

| TVt | 0.2272 | 5.699*** | 0.3467 | 6.114*** |

| INTERNETt | −0.0517 | −1.339 | 0.0045 | 0.092 |

| PRESSt | 0.2500 | 1.822* | −0.1764 | −2.310** |

| OUTDOORt | 0.0416 | 1.929* | 0.0842 | 2.181** |

| PCGt | 0.0381 | 2.512** | 0.0516 | 1.887* |

| CPIt | 0.0091 | 0.457 | 0.0177 | 0.913 |

| SIZEt | −0.0422 | −0.334 | −0.3835 | −4.097*** |

| DEBT_RATIOt | 0.0707 | 0.399 | 0.1254 | 1.512 |

| CASH_RATIOt | −0.1021 | −1.413 | −0.1361 | −3.031*** |

| Obs. | 1,023 | 1,016 | ||

| Adj. R2 | 67.56% | 71.69% | ||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| Quarter FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| St. error clustering | Firm | Firm | ||

- Notes: This table reports coefficient estimates of the following OLS specification: The sample used in this table is partitioned by the book-to-market ratio. Each model includes industry, quarter, and year fixed effects. The sample period covers 2004–2014. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively. See Appendix 2 for variable definitions.

Our results suggest that when there are more growth opportunities, press advertising behaves like fixed costs, evidenced by the negative association. Fixed costs may indicate that there is an optimum level of spending. Once the optimum level is reached, the spending per unit will increase while the output level remains constant. This is plausible, because for growing firms, the economic benefits of advertising spending may take more time to be realized, while more mature firms are likely to realize these benefits more quickly given their established customer base.

Overall, the results in Table 6 supplement our findings in Table 5. Collectively, they show that there is a mismatch between advertising spending and contemporaneous sales. We show that this mismatch is driven by various advertising media vehicles. We also show that the growth opportunities exacerbate the existing mismatch between advertising expenditures and sales.

Industry Sectors and Size-Based Differences

Firms may pursue different strategies to compete in the marketplace. Prior research finds significant variation in advertising and promotion intensity across consumer versus industrial sector firms (Chauvin and Hirschey 1993; Graham and Frankenberger 2000). In certain sectors (e.g., consumer goods and consumer services), firms target large audiences and often rely on advertising in pursuing low costs and differentiation strategies for their brands and services.

Similarly, another consideration in the relevance of advertising expenditures is firm size. By virtue of their size, large firms may be better equipped than small firms to afford large outlays on advertising and may benefit from economies of scale and scope in advertising. As a result, advertising expenditures are more likely to be effective for relatively larger firms (Chauvin and Hirschey 1993; Hirschey and Spencer 1992; Shah et al. 2009).

More recently, Shah et al. (2021) find industry sector and size-based differences in the association between advertising expenditures and firms' future performance. Specifically, they find that advertising has a positive and statistically significant impact on firms' future earnings for both large-firm and small-firm subsamples. However, their findings show that the size of the coefficient of advertising for the large-firm subsample is larger than that of the small-firm subsample. Lastly, they show that advertising has a positive influence for firms in the consumer goods and consumer services sectors, while this association becomes insignificant for the industrial and technology sectors.

Following the findings in the literature, we revisit our primary findings. We split our sample based on industry sectors and size. First, we split our sample into two: firms in the consumer discretionary and consumer staples sectors and all other firms.8 We report our findings in Table 7. Model (1) shows the results for the consumer discretionary and consumer staples sectors, while model (2) shows the results for all other sectors. Both models reveal that the coefficients on TV are significantly positive, while the coefficients on PRESS are insignificant. Our results show a negative coefficient on INTERNET, while model (2) shows a positive coefficient on INTERNET. Both of these coefficients are significant at 10%. Only model (1) reveals a significantly positive coefficient on OUTDOOR. Our results suggest that firms, regardless of the sector, benefit from using TV as an advertising media vehicle, and the economic benefits can be observed in the current sales performance. However, the (potential) benefits and costs of expenditures on other media vehicles largely depend on the sector.

| Model (1) | Model (2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sectors: Consumer discretionary and consumer staples | Sectors: All other | |||

| Standardized estimates | t-value | Standardized estimates | t-value | |

| Intercept | 0.0000 | 1.73* | 0.0000 | 3.77*** |

| TVt | 0.2767 | 3.58*** | 0.2083 | 5.21*** |

| INTERNETt | −0.1084 | −1.90* | 0.0931 | 1.73* |

| PRESSt | −0.0299 | −0.37 | −0.0644 | −0.98 |

| OUTDOORt | 0.2251 | 4.52*** | 0.0614 | 1.47 |

| PCGt | 0.0465 | 1.61 | 0.0361 | 3.29*** |

| CPIt | 0.0170 | 1.00 | 0.0435 | 2.35** |

| SIZEt | −0.1946 | −0.90 | −0.2513 | −2.00** |

| DEBT_RATIOt | 0.1489 | 1.31 | 0.0061 | 0.09 |

| CASH_RATIOt | −0.0124 | −0.14 | −0.2941 | −4.06*** |

| Obs. | 1,149 | 890 | ||

| Adj. R2 | 56.66% | 74.19% | ||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| Quarter FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| St. error clustering | Firm | Firm | ||

- Notes: This table reports coefficient estimates of the following OLS specification: The sample used in this table is partitioned by sectors (i.e., consumer discretionary and consumer staples and other). Each model includes industry, quarter, and year fixed effects. The sample period covers 2004–2014. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively. See Appendix 2 for variable definitions.

Next, we split our sample based on whether a firm's size is above the sample median for the quarter. We report our findings in Table 8. Model (1) shows the results when the SIZE variable is above the sample median for the quarter, while model (2) shows the results when the SIZE variable is below the sample median for the quarter. Our findings are consistent and similar to those reported in Table 6. To the extent that SIZE may capture growth opportunities, this is not surprising.

| Model (1) | Model (2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| > median (size) | < median (size) | |||

| Standardized estimates | t-value | Standardized estimates | t-value | |

| Intercept | 0.0000 | 0.48 | 0.0000 | 3.84*** |

| TVt | 0.1796 | 4.51** | 0.2229 | 3.64*** |

| INTERNETt | 0.0294 | 0.91 | −0.0008 | −0.03 |

| PRESSt | 0.3014 | 1.96* | −0.1666 | −4.01*** |

| OUTDOORt | −0.0156 | −0.30 | 0.2198 | 5.61*** |

| PCGt | 0.0211 | 1.14 | 0.0574 | 2.53** |

| CPIt | 0.0337 | 2.54** | 0.0282 | 1.38 |

| SIZEt | 0.0234 | 0.12 | −0.3866 | −4.43*** |

| DEBT_RATIOt | 0.0743 | 0.73 | 0.2238 | 2.77*** |

| CASH_RATIOt | 0.0811 | 1.57 | −0.1748 | −3.90*** |

| Obs. | 1,226 | 813 | ||

| Adj. R2 | 69.95% | 70.28% | ||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| Quarter FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| St. error clustering | Firm | Firm | ||

- Notes: This table reports coefficient estimates of the following OLS specification: The sample used in this table is partitioned by the firm size. Each model includes industry, quarter, and year fixed effects. The sample period covers 2004–2014. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively. See Appendix 2 for variable definitions.

Collectively, Tables 7 and 8 show that while advertising expenditures bring economic benefits, revenue-expense matching is not fully achieved. To the extent that significantly negative associations reveal poor matching, we report that firm size and sectors play a role in how economic benefits from various advertising vehicles match with the current sales and advertising expenditures on media vehicles. At the very least, our results suggest that there is noise over the economic benefits gained. Our results support our main argument that revenue-expense matching varies by media vehicles.

Robustness Tests

In this section, we discuss three sensitivity analyses to ensure the robustness of our results. First, we repeat our main findings in Table 5, using one-period lagged independent variables. Using the one-period lagged independent variables addresses endogeneity concerns and rules out reverse causality (to some extent). We report our findings in Table 9. The coefficient estimates show that advertising expenditures on TV and outdoor are positively associated with sales, significant at 1%. On the other hand, advertising expenditures on Internet and press are both insignificant in our model. Even when we use lagged independent variables, our findings remain consistent.

| Model (1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Standardized estimates | t-value | |

| Intercept | 0.0000 | 2.52** |

| TVt−1 | 0.2438 | 4.36*** |

| INTERNETt−1 | −0.0125 | −0.32 |

| PRESSt−1 | −0.0653 | −1.03 |

| OUTDOORt−1 | 0.1426 | 3.01*** |

| PCGt−1 | 0.0005 | 0.03 |

| CPIt−1 | −0.0208 | −0.83 |

| SIZEt−1 | −0.2263 | −1.74* |

| DEBT_RATIOt−1 | 0.1218 | 1.54 |

| CASH_RATIOt−1 | −0.1216 | −2.29** |

| Obs. | 1,925 | |

| Adj. R2 | 64.04% | |

| Year FE | Yes | |

| Quarter FE | Yes | |

| Industry FE | Yes | |

| St. error clustering | Firm | |

- Notes: This table reports coefficient estimates of the following OLS specification: The model includes industry, quarter, and year fixed effects. The sample period covers 2004–2014. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively. See Appendix 2 for variable definitions.

Second, we consider the possibility that the economic benefits of press and outdoor advertising may be observed with delay, while TV and Internet advertising may be recognized more quickly. One possible explanation for this is that television and Internet ads directly reach the media user and command their attention by interrupting the audience's real-time activities or by taking advantage of their obligations to be in a given place. On the other hand, press and outdoor media vehicles are not as intrusive because users of these media can observe ads in their own time. They allow for highly self-selected ad experiences because media users have the liberty to skip ads that hold little or no interest for them or focus only on the ones that they have interest in or are already familiar with. We revise our primary model to include one-period lagged variables of press and outdoor advertising, while we use current values of TV and Internet advertising. We report our findings in Table 10. Our findings are virtually the same as those reported in Table 10.

| Model (1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Standardized estimates | t-value | |

| Intercept | 0.0000 | 2.53** |

| TVt | 0.2313 | 4.06*** |

| INTERNETt | −0.0115 | −0.32 |

| PRESSt−1 | −0.0638 | −1.05 |

| OUTDOORt−1 | 0.1166 | 2.82*** |

| PCGt | 0.0462 | 2.56** |

| CPIt | 0.0232 | 1.95* |

| SIZEt | −0.2525 | −1.93* |

| DEBT_RATIOt | 0.1039 | 1.26 |

| CASH_RATIOt | −0.1186 | −2.16** |

| Obs. | 1,925 | |

| Adj. R2 | 63.47% | |

| Year FE | Yes | |

| Quarter FE | Yes | |

| Industry FE | Yes | |

| St. error clustering | Firm | |

- Notes: This table reports coefficient estimates of the following OLS specification: The model includes industry, quarter, and year fixed effects. The sample period covers 2004–2014. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively. See Appendix 2 for variable definitions.

Third, we run our model by only including nonzero advertising variables. We report our results in Table 11. Our sample size significantly drops, and we only have 461 observations. Despite the small sample size, our findings remain qualitatively similar. The coefficients on TV and OUTDOOR are positive, significant at 1%. The coefficient on INTERNET remains insignificant. These results are consistent with our earlier results. Surprisingly, we find the coefficient on PRESS to be significantly positive (at the 1% level). We note that firms that use all four media vehicles in the same quarter-year tend to have larger book-to-market ratios. Thus, these results support what we report in Table 6.

| Model (1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Standardized estimates | t-value | |

| Intercept | 0.0000 | 1.19 |

| TVt | 0.2438 | 2.76*** |

| INTERNETt | 0.1670 | 1.62 |

| PRESSt | 0.2108 | 3.63*** |

| OUTDOORt | 0.2784 | 4.79*** |

| PCGt | 0.0348 | 1.97** |

| CPIt | 0.0295 | 1.23 |

| SIZEt | 0.0947 | 0.41 |

| DEBT_RATIOt | −0.0920 | −0.62 |

| CASH_RATIOt | 0.1520 | 1.7* |

| Obs. | 461 | |

| Adj. R2 | 77.31% | |

| Year FE | Yes | |

| Quarter FE | Yes | |

| Industry FE | Yes | |

| St. error clustering | Firm | |

- Notes: This table reports coefficient estimates of the following OLS specification: The model only includes nonzero advertising variables and includes industry, quarter, and year fixed effects. The sample period covers 2004–2014. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively. See Appendix 2 for variable definitions.

5 DISCUSSION

The results of this paper provide a novel insight into how media advertising expenditures are associated with contemporaneous revenues. This research highlights new opportunities to develop theory on the issue of revenue-expense matching. It also creates future opportunities around the optimal allocation of advertising budget among media advertising.

We organize the following discussion around a series of three propositions that signify potential implications for theory and practice informed by our findings.

Proposition 1.The poor matching between advertising expenditures and sales may be explained by behavioral factors.

Our results show that there is a positive association between total advertising expenditures and sales. However, they also show that not all advertising expenditure has a positive association with sales. The impact of advertising expenditures on sales largely depends on the media vehicle. Neither US GAAP nor IFRS requires firms to disclose advertising expenditures on media vehicles. Therefore, the implications of advertising expenditures by various media vehicles for financial reporting are limited by our understanding of advertising expenditures in aggregate. Our results would suggest that media vehicles create noise over the economic benefits gained from advertising and indicate poor matching between advertising expenditures and sales.

Advertising media vehicles can influence the perception of ad intrusiveness and offer different opportunities for ad avoidance. Television and cinema ads directly reach the media user and command their attention by interrupting the audience's real-time activities or by taking advantage of their obligation to be in a given place. While avoiding television and cinema ads is possible, it can be costly (e.g., missing the content) or requires more effort. For instance, media users can remove a television commercial from their attention by ignoring it (a cognitive strategy), leaving the room (a behavioral strategy), or switching channels (a mechanical strategy). However, behavioral and mechanical strategies may cause the media users to miss the editorial content they were aiming to focus on. If they want to make sure they do not miss the editorial content, they may have to wait for the ads to end.

On the other hand, Internet, press, and outdoor media vehicles are not as intrusive because users of these media can observe ads in their own time. They allow for highly self-selected ad experiences because media users have the liberty to skip ads that hold little or no interest for them or focus only on the ones that they are interested in or already familiar with. There is little effort or cost to avoid self-selected ads. For instance, if media users see an ad in a newspaper, they can remove the ad from their attention by ignoring it or turning the page and setting aside an advertising section. In this case, the behavioral strategy will help the media users to skip the ad without necessarily missing any other content.

Due to the level of ad avoidance, not every media vehicle will succeed in generating contemporaneous sales. Therefore, expenditures on media vehicles that disseminate information and elicit opinions by forcing their way into the audience and grabbing attention might be better matched with current revenues. To our knowledge, there have been no studies considering the role of behavioral factors in the revenue-expense matching principle. We hope that future research will explore this avenue.

Proposition 2.Poor matching between advertising expenditures and sales will drive cost inefficiencies.

Corporate financial reports do not provide investors with an accurate view of the value-creation process within the firm. We argue that the lack of financial and nonfinancial information on the firms' value drivers, such as advertising expenses, drive cost inefficiencies. Firms investing large amounts in advertising will report lower book values. They will be significantly affected by the immediate recognition of these expenses and the delayed recognition of the benefits in accounting earnings, particularly if they are small and have a record of reported losses.

When the market is not fully aware of advertising spending, budgeting methods and measures used for analysis may provide inadequate information for effective output-based performance evaluation and control monitoring. Budget analysis that fails to consider available input substitution possibilities in response to poor expense-revenue matching may result in lost opportunities for cost savings. We interpret our findings as suggesting that advertising spending provides input substitution possibilities.

We hope that future research can examine a cost function that uniquely represents the underlying production function and includes input prices (e.g., advertising spending), the state of disclosure, and output level (i.e., sales) as variables. Such a model may be capable of providing evidence of cost-efficient behavior.

Proposition 3.The association between advertising expenditures and sales is moderated by growth and value-creation opportunities.

Investment horizons (Jacobs 1991) and the pursuit of corporate entrepreneurship (Zahra 1993) vary from one firm to another. The opportunities that managers believe to exist for their firms can profoundly influence their decisions about advertising expenditures (i.e., budget, media outlet). Advertising expenditures may support and generate growth and value-creation opportunities by emphasizing product and process innovations.

Factors such as competition, the growth of overall demand, and changes in customer preferences may set limits on advertising expenditures. More specifically, growth opportunities lead to high unpredictability of customers and competitors and high rates of change in market trends and industry innovation (Miller 1987); therefore, these dynamics will influence advertising expenditures.

We hope that future research can explore model(s) where the choice of advertising expenditures is a function of growth and value-creation opportunities, and its impact on sales demand creation. Such models will enhance our understanding of the accounting treatment of advertising expenditures.

6 CONCLUDING REMARKS

This study demonstrates the contemporaneous sales effects of advertising expenditures categorized by media vehicle. We find that while aggregate advertising expenditures have a positive association with sales, this association does not necessarily exist for expenditures on each media vehicle. We find that advertising expenditures on TV and outdoor are positively associated with sales, while this association becomes insignificant for advertising expenditures on Internet and press. To provide further insights, we also examine how the sensitivity of our results changes conditional on growth opportunities, sector, and size-based differences. Our results show that when there are more growth opportunities, the association between advertising expenditures on press and sales becomes significantly positive. Our results suggest that firms benefit from using TV as an advertising media vehicle and the economic benefits can be observed in the current sales performance under various conditions. However, the benefits and costs of expenditures on other media vehicles largely depend on the growth opportunities and sector.

Overall, our study offers important evidence that the contemporaneous relationship between sales and advertising expenditures varies by media vehicle. We believe this finding to have implications for the matching principle, a principal concept in accrual accounting. We offer three propositions based on our findings for future research to address. First, we discuss that behavioral factors may explain the poor matching between revenues and expenses. Second, we argue that advertising expenditures not reflected in contemporaneous revenues are likely to drive cost inefficiencies. Last, we offer an explanation that growth opportunities may be a moderator between the matching of advertising expenditures and sales. We hope that there will be future research addressing these issues.

Our study is subject to several caveats. First, although we confront the endogenous nature of advertising expenditure using various sensitivity tests, we cannot fully dismiss these threats. Second, our study focuses only on the publicly traded UK firms in our sample, and our empirical findings are limited to firms that (usually) advertise across the different media vehicles that our study covers. Our conclusions are limited to our sample, and our findings cannot be generalized to small, local firms that do not advertise regularly.

Third, due to the proprietary nature of advertising expenditures on media vehicles, our sample period is limited and does not cover the period after 2014. Further, the lack of results with Internet advertising may be due to the limited use of the Internet during the sample period covered in this study. The nature of advertising is changing every day, and the importance of social media is increasing. The changing nature of advertising strategies may affect the matching between sales and these expenditures. We hope that our results highlight the importance of disclosure of advertising expenditures, but we acknowledge that our findings cannot speak to the changing nature of advertising. Last, our data do not allow us to distinguish various outlets within the media vehicles we covered in this study. For instance, our study cannot speak to the effectiveness of social media advertising even though it is part of Internet advertising.

While our results are subject to research design choices, they nevertheless offer compelling evidence that advertising media vehicles have different roles in influencing sales performance. We suggest new potential avenues for theory development related to the use of advertising media vehicles, and their implications for financial reporting. The findings of this study may also help devise more successful advertising strategies and be of interest to managers.

Endnotes

APPENDIX 1

This Appendix describes the various media vehicles from which the advertising data are collected.

1 Television and Cinema

1.1 Television

The United Kingdom has a collection of free-to-air and subscription services over a variety of distribution media, through which there are over 480 channels for consumers, as well as on-demand content. As of 2003, 53.2% of households watch through terrestrial, 31.3% through satellite, and 15.6% through cable (Adda and Ottaviani 2005). TV advertising keeps track of commercial occurrences and advertising activities information over 100 television, radio, and interactive services broadcast via the United Kingdom's terrestrial television network, cable television services, and satellite television 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

1.2 Cinema

Cinema advertisements include all the ads shown in a movie theater right before the film starts. Cinema ads, on average, last between 15 and 60 seconds. In the United Kingdom, there are no intermissions at movie theaters, so all relevant ads are shown at the beginning of each film.

2 Press

2.1 Magazines

Magazines include all paid advertising space and expenditure data in consumer and local magazines.

2.2 Newspapers

Newspapers include all advertising space in daily and Sunday newspaper editions and Sunday magazines.

3 Internet

Advertising expenditure information is measured for over 1,000 sites and 50,000 brands in the United Kingdom. A proprietary spider probes the sites on an ongoing basis and captures and stores every image on a page.

4 Outdoor

Outdoor advertising reaches consumers while they are outside their homes. The Outdoor Advertising Association of Great Britain (OAA)9 organizes the outdoor market into three sectors: roadside, transport, and retail. Roadside includes phone kiosks, display offers (e.g., 6 sheets), billboards (e.g., 48 sheets, 96 sheets), large-format special builds, and banners. Transport covers railway and underground systems, airports, buses, taxis, and truck sides, etc. Retail includes opportunities in health and leisure centers and sites seen at shopping malls, supermarkets, and petrol stations, plus activity such as screens and posters. According to OAA, the United Kingdom is Western Europe's largest market for outdoor advertising.

APPENDIX 2: VARIABLE DEFINITIONS

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

|

Total sales of firm i, quarter t, scaled by total assets |

|

TV and cinema advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t, scaled by total assets |

|

Internet advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t, scaled by total assets |

|

Press advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t, scaled by total assets |

|

Outdoor advertising expenditures of firm i, quarter t, scaled by total assets |

|

Private consumption growth, which measures the growth in private consumption in the United Kingdom while adjusting for inflation, in quarter t. Private consumption includes all purchases made by consumers, such as food, housing (rents), energy, clothing, health, leisure, education, communication, and transport, as well as hotels and restaurant services. It does not include households' purchases of dwellings, which are counted as household investment |

|

The Consumer Price Index, which is a price index that measures the average cost of goods and services purchased by the typical household in the United Kingdom, in quarter t |

|

Firm size is calculated as the natural logarithm of a firm's total employees |

|

Debt ratio is calculated as total short-term and long-term debt as a percentage of total assets |

|

Cash ratio is calculated as the total cash balance as a percentage of current liabilities |

|

Book-to-market ratio |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Advertising data are available from the CreativeClub database, which is a UK-based advertising database run by Ebiquity (formerly known as Thomson Intermedia). The remaining data are available from public sources identified in the paper.