Barriers to Transferring Auditing Research to Standard Setters†

Abstract

enAuditing researchers have published over 24,000 academic articles (Google Scholar September 2016) since 1970. Auditing standard setters and regulators frequently describe an inability to engage with and utilize this research to make evidence-informed standard setting and regulatory decisions. For society to benefit from the large investment in audit research, the knowledge needs to systematically and effectively transferred to auditing policymakers. We draw on the knowledge transfer literature to identify barriers to transferring academic knowledge and discuss how these concepts apply to audit standard setting. We then examine a paradigmatic example of academic knowledge transfer to policymaking: evidence-based medicine. Based on this analysis, we propose a tentative strategy to address the barriers to transferring audit research knowledge to policymaking and sketch out potential avenues for research. We conclude with an illustrative example of how to implement a knowledge transfer strategy that is effective in systematically transferring knowledge in other policymaking settings to the context of a specific audit standard-setting project: group audits.

Abstract

frRésumé

Obstacles à la transmission des fruits de la recherche en audit aux normalisateurs

Depuis 1970, les chercheurs dans le domaine de l'audit ont publié plus de 24 000 articles universitaires (Google Scholar, septembre 2016). Les organismes de normalisation et les autorités de réglementation en audit déplorent fréquemment l'impossibilité dans laquelle ils se trouvent de donner suite à ces recherches et de les utiliser dans la prise de décisions fondées sur les faits dans leur travail de normalisation et de réglementation. Pour que la société puisse bénéficier des sommes importantes qui sont investies dans la recherche en audit, les connaissances doivent être transmises de manière systématique et efficace aux décideurs en audit. Les auteurs puisent dans la documentation relative à la transmission des connaissances pour cerner les obstacles à la transmission des connaissances universitaires et traiter du mode d'application de ces connaissances à la normalisation en audit. Ils se penchent ensuite sur un exemple paradigmatique de transmission de connaissances universitaires aux décideurs : celui de la médecine factuelle (fondée sur les données). Leur analyse les amène à proposer une stratégie expérimentale en vue d’éliminer les obstacles à la transmission aux décideurs des connaissances issues de la recherche en audit et à esquisser des pistes de recherche possibles. Ils concluent par un exemple visant à illustrer comment mettre en œuvre une stratégie efficace propre à assurer la transmission systématique des connaissances dans d'autres cadres décisionnels, dans le contexte d'un projet particulier de normalisation en audit : celui des audits de groupes.

The objectives of this article are (i) to examine the barriers encountered by auditing regulators and standard setters (hereafter, auditing policymakers) to systematically utilizing the large extant and growing body of audit academic research and (ii) to identify potential strategies to enhance systematic and effective academic audit knowledge transfer that are suggestive for developing a research agenda. There are numerous studies by academic researchers and professional accounting bodies that suggest that the current knowledge translation process is not as successful as needed or desired, for example, Evans, Burritt, and Guthrie (2011) in Australia; Leisenring and Johnson (1994), AAA Research Impact Task Force (2009), and Franzel (2016) in the United States; Humphrey, Loft, and Woods (2009) in the United Kingdom; Sinclair and Cordery (2016) in New Zealand; and Monitoring Group (2017) internationally.

We are not suggesting that audit knowledge transfer has not occurred between audit researchers and the broader audit practice community (e.g., Bell and Wright, 1995). However, the mere fact that it took a team of researchers two years in the 1990s to document that such transfer occurred (Bell and Wright, 1995) strongly suggests that the knowledge transfer was ad hoc, not systematic.1 What we are examining is the barriers to systematically and effectively ensuring knowledge transfer to audit policymakers on an ongoing sustainable basis.2

To do so, we first develop a theory-based understanding of the academic knowledge transfer problem by identifying, analyzing, and applying theoretical perspectives on knowledge codification (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) and barriers to knowledge transfer (e.g., Zander and Kogut, 1995). We examine how a knowledge-based solution (i.e., an auditing standard) is produced using knowledge transferred from various evidence sources (e.g., public accounting firm practices, standard setters' personal auditing expertise, academic research, etc.). Our analysis of this literature sensitizes us to factors that promote or inhibit inclusion of diverse knowledge sources in the knowledge-based solution, enabling us to identify analogous barriers in audit standard setting.

Next, in an attempt to overcome these barriers, we examine literature on evidence-based policymaking (Campbell Collaboration, 2015) and evidence-based management (Rousseau, 2012). Evidence-based policymaking has been employed with varying success in social work (e.g., Gambrill, 2006), public education, the justice system, and many other areas (Campbell Collaboration, 2015). The evidence-based policymaking framework originated from the evidence-based medicine movement (EBM), which sought to overcome the challenges of using academic research knowledge to create medical practice guidelines (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, and Richardson, 1996; Sackett, 2000). Although EBM started in the 1990s with a focus on medical (especially drug and diagnostic) interventions, where randomized clinical trials were the “gold standard” of evidence (Ball et al., 2001), these practices were adapted to wider domains of health policy (Ammerman, Smith, and Calancie, 2014) where more complex sets of evidence needed to be transferred. In particular, we examine EBM's knowledge translation framework that facilitates systematizing, analyzing and transferring the broad and always rapidly growing research evidence via development of practice guidelines (e.g., Scott and Guyatt, 2014). We propose that these practices have strong potential to enhance academic knowledge transfer in the audit standard-setting context.

To be clear, “evidence-based” means that the policymakers make an informed decision explicitly including evidence that comes from underlying academic research, in addition to inputs from practitioners, other regulators/guideline producers, and parties that have traditionally been engaged in the policymaking process (e.g., for analysis of such parties in financial accounting see Tandy and Wilburn, 1992, 1996).3 Even in the domain of EBM the research knowledge being transferred does not set the policy prescription except in rare areas such as drug safety (Sackett et al., 1996). In other words, the term “evidence-based” can be better described as “evidence-informed” policymaking (Leuz, 2018; Teixeira, 2014), as rarely will the research evidence lead to “one right” policy. Further, our concern is focused on the transfer, not the potentially political processes that occur in the standard-setting environment (e.g., Power, 1993; Watts and Zimmerman, 1979) which is beyond the scope of this article.

Finally, to illustrate how an enhanced knowledge transfer strategy could be implemented in audit standard setting, we focus on one key academic knowledge transfer tool from EBM: the production of research syntheses (Lambert, 2006). We provide a detailed example of how audit policymakers and academics could collaborate in an iterative manner to produce a research synthesis in the current audit standard–setting institutional environment.4 Our illustrative example is a specific, researchable question from the public records surrounding the IAASB's group audit project (IAASB, 2007). We suggest that a properly executed research synthesis could have informed one central issue in the group audit standard revising process—an issue that contributed to redrafting the standard several times and producing two exposure drafts before the standard was finalized (i.e., ISA 600 [Revised and Redrafted] IAASB, 2007).

Background: International Audit Standard-Setting Process

The audit standard-setting process is marked by increasing internationalization, leading to the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) being the primary creator audit standards outside the United States. At present, 113 countries employ IAASB standards (IAASB, 2017), either directly or after review and adoption by a national standard setter (e.g., in Canada, after the Canadian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board reviews and adopts the standard (CPA Canada, 2017)).5

Table 1 shows the IAASB's process for developing a new standard (PIOB, 2015). National standard setters follow variants of this process when reviewing for adoption of an IAASB standard for their country (e.g., CPA Canada, 2017). That process contains no explicit requirement to consider academic evidence; however, there are vague references to consideration of “research” in Steps 1 and 4. Further, audit academics could provide research-based evidence in response to the call for public comments on exposure drafts at Step 5.

|

- * Adapted from PIOB (2015).

Knowledge Theories Applied to Auditing Policymaking

Rather than reviewing the knowledge codification and knowledge transfer literature and subsequently apply it to the auditing context, we interweave the theory presentation and our views on its application to auditing within each subsection. Our goal is to allow the reader to consider how we have translated the theory into our context as we introduce the theoretical notions, rather than holding them in abeyance until after we present the various strands of theory.

The Nature of Codified Knowledge

A standard can be considered as a codification of the “state of the art” of existing knowledge, which itself can be defined as a “justified true belief” based on evidence (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka and von Krogh, 2009). Knowledge initially is developed by a person because of responding to an environmental need or challenge. When the challenge is common to others, then there will likely be a call to codify that knowledge so it can be transferred to others. One way to codify knowledge is via creation of documented models and processes (Hansen, Nohria, and Tierney, 1999; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Morris and Empson, 1998; Hansen, 1999; Szulanski, 1996). However, knowledge has two components, only one of which is easy to document: explicit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is defined as knowledge represented in a formal, systemic language that can be applied to a broad variety of tasks without recourse to the person(s) who codified it (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995).

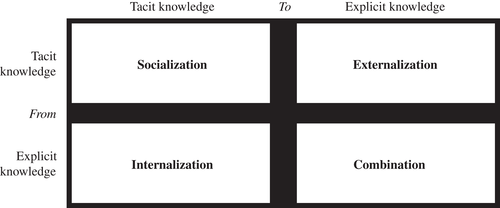

Effective knowledge transfer, however, requires that the person(s) who are involved in codifying the practice to convey their personal tacit knowledge, defined as knowledge about how-to-do actions or activities undertaken to apply explicit knowledge (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995). Tacit knowledge plays two roles in transferring codified explicit knowledge. First, tacit knowledge initially aids in codifying explicit knowledge through a translation process called “externalization” that readies the knowledge for transfer in a way that the developer of the knowledge does not have to be present in order for the explicit knowledge to be used (Nonaka, 1994). Second, in a process called “internalization,” the resulting new codified knowledge facilitates the practitioner's implementation of it by triggering the practitioners' use of their own existing tacit knowledge (Nonaka, 1994). Figure 1 (Nonaka, 1994: 19) illustrates the four processes that occur in the translation of one form of knowledge to another.

Knowledge creation processes: Translating explicit knowledge to and from tacit knowledge (Adapted from Figure 1 of Nonaka (1994: 19))

Successful codification depends, in part, on the facility of the person(s) doing the codification to convey the requisite tacit knowledge about how to implement that which is codified (Hansen, 1999).

Theory tells us that there are several processes involved that allows this individual initiated development of explicit knowledge to be combined with the tacit knowledge to effectively implement the codified knowledge. The “combination” process (Nonaka, 1994) involves the use of social processes (i.e., deliberation and debate) to combine different bodies of explicit knowledge held by individuals into codified knowledge. The “reconfiguration” process happens through sorting, adding, re-categorizing, and re-contextualizing the existing knowledge and fitting the new knowledge into that body. The goal of knowledge codification is to provide a basis for action when the parties creating the codification are not the ones applying the knowledge to an issue.

The codification of explicit knowledge starts with the realization by policymakers that a new best practice response needs to be created (i.e., a new standard) or the realization that an existing standard is no longer as effective in achieving its goals as it once was. This “realization” process prompts the search for evidence by a process of adding, re-categorizing and re-contextualizing how this “new” codified knowledge can fit into the existing practice (in other words, it is not assumed that “the evidence or knowledge speaks for itself”).

Auditing policymaking application: We conceptualize auditing standards as codified explicit knowledge that results from transferring the best available evidence about how to act. We conceptualize the development of auditing standards as the transfer of practitioners' and others' explicit knowledge to the policymaker, combined with other viewpoints (e.g., other standard setters, academic researchers), and integrated by the policymaker into a codified “best practices” standard that can be communicated to other auditors.

The standard-setting process allows for deliberation and debate among the standard setters, and then with the broader audit community, that is, it is a process of adding, re-categorizing and re-contextualizing how this knowledge can fit into the existing body of knowledge. As with all codified knowledge transfer, the inability to transfer the needed tacit knowledge to implement the policymakers' intentions presents a difficulty that needs to be overcome.

Tacit knowledge about auditing resides in practitioners, standard-setting committees, and task forces. Tacit knowledge is the area where academic audit researchers have the least to offer, as they do not deal with practice in their everyday research. This acknowledgement reinforces the argument that transfer from academic audit research evidence to policymaking will never be deterministic of the standard. Indeed, ignoring the tacit knowledge of practitioners in favor of academic research can lead to standards that are not implementable, or are only implementable at great cost.6 However, this deficit is not a reason to ignore academic audit research, but provides further understanding as to why “evidence-based” standard setting needs to be understood as “evidence-informed.”

Organizational Knowledge Development

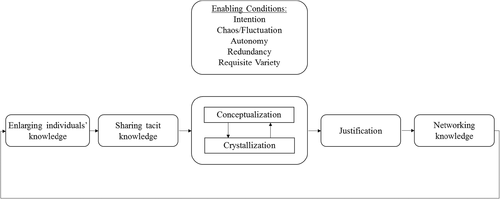

…triggered by successive rounds of meaningful “dialogue.” In this dialogue, the sophisticated use of “metaphors” can be used to enable team members to articulate their own perspectives, and thereby reveal hidden tacit knowledge that is otherwise hard to communicate. Concepts formed by teams can be combined with existing data and external knowledge in a search of more concrete and sharable specifications (i.e. conceptualization). This combination mode is facilitated by such triggers as “coordination” between team members and other sections of the organization and the “documentation” of existing knowledge. Through an iterative process of trial and error, concepts are articulated and developed until they emerge in a concrete form (i.e. crystallization).

After crystallization, the newly codified knowledge must be “synthesized” (networked) into existing knowledge via a process where the “new, useful, practical, valid and important knowledge is connected to the knowledge system in the organization” (Nonaka, von Krogh, and Voelpel, 2006: 1183). Figure 2 outlines the conceptual model for the organizational knowledge creation process.

Process of generating knowledge in an organization (Adapted from Figure 3 of Nonaka (1994: 28)).

Auditing policymaking application: We suggest that this description of knowledge development is highly representative of the current auditing standard-setting processes. Indeed, audit policymaking is very much the result of a team effort (standard setters, task forces, etc.) where socialization occurs and facilitates the sharing of members' experiences and perspectives. This framework for knowledge codification also sheds light on reasons why knowledge from practitioners and experts is more successful than academic knowledge from researchers in affecting policymaking. Knowledge from practitioners and experts is more likely to undergo an iterative dialogue that can lead to both externalization and internalization, and ultimately be synthesized by the policymakers. Furthermore, practitioners and experts are better able to understand the nuances of how to fit a new proposed codified auditing standard into the body of existing standards as it undergoes a “synthesizing” process. This conceptual analysis suggests that there needs to be a better process for academic audit research to be effectively transferred to policymakers given the built-in advantages other forms of knowledge have in this environment.

- The users who create new knowledge and the providers of information/evidence that goes into creating that knowledge are different;

- The users who create new knowledge and the providers of information/evidence have distinctly different reward structures associated with their use of or supplying such information; and

- There is a nontrivial matching problem between the users who create the knowledge and the suppliers of information/evidence that can inform the creation of the knowledge. In particular, users cannot easily identify appropriate information/evidence from among the set of available information/evidence.

In this knowledge market, users are likely to engage in sequential search starting with a subset of known and credible information/evidence suppliers. Hence, the supplier of information/evidence in such a market needs to be able to gain a reputation for credible production of evidence.

Auditing policymaking application: This conceptual analysis suggests that an additional characterization of the current knowledge transfer problem from audit research to policymakers is the result of a market failure (e.g., Watts and Zimmerman, 1979). That is, auditing academic research has generally been unsuccessful in obtaining policymakers' attention in a competitive market for knowledge (Hansen and Haas, 2001). Based on the apparent low influence of audit academic research on policymakers, theory would suggest auditing academic research is seen as neither a relevant nor a reliable source of knowledge by policymakers. Analyzing audit academic research as codified knowledge, we suggest that in light of our previous analysis of the need for tacit knowledge to interpret codified knowledge, this low use is because of the amount of tacit knowledge that the potential user of auditing research must have to interpret such research (Zander and Kogut, 1995). Audit research in journal articles is in a form that is unfamiliar to the potential user, thus creating a barrier to his (her) knowledge acquisition (Zander and Kogut, 1995). Furthermore, the amount of audit research published is daunting (over 24,000 academic articles in auditing) and the process to transform it and to ease its translation into information/evidence that can affect the policymakers' incorporation of it into new codified knowledge (i.e., standards) is not well understood. Finally, it is not clear whether auditing policymakers can distinguish the relative quality of different research studies that make up the body of research evidence.

Knowledge Transfer Barriers

- incentives of the evidence provider to collaborate with the evidence recipient that are commensurate with the effort required from the provider to support the transfer;

- differences in the amount of overlapping understanding of the meaning of the conveyed information, including its tacit elements necessary for use and interpretation (Nonaka, 1994);

- recipient's motivation to seek or accept knowledge from unknown or indeterminate quality resources can also vary widely; and

- different recipients may vary in their ability to incorporate information from nontraditional sources of knowledge (i.e., their absorptive capacity) because of their lack of a shared tacit understanding about how the information is created and its reliability.

Auditing policymaking application: We suggest that the challenge of transferring auditing research evidence into the policymaking process is one very much akin to the stickiness in transferring knowledge where one conceptualizes audit academics as the evidence providers and audit policymakers as the recipient. Auditing research knowledge fits into the category of “complex and causally ambiguous practices” even to the committed PhD student (Kinney Jr., 2003), let alone to the practice-based policymaker. The common prescription of more direct exchanges between the recipient and the evidence provider, to the extent they are attempted, does not seem to systemically work in the auditing context (Salterio et al., 2018).

The incentives for academics to attempt this communication are limited (for an early discussion of this barrier see Leisenring and Johnson, 1994). Salterio et al. (2018) document and evaluate eight means that have been employed to date to attempt to have systematic and effective audit knowledge transfer to policymakers. These means vary from having an audit academic on the standard-setting board to the PCAOB-Auditing Section literature synthesis project. They conclude based on a conceptual analysis that none of these means consistently achieved the objective.

Furthermore, to date, auditing policymaking has been relatively immune to pressures to demonstrate that their standards and regulations are evidence-based (although this is changing; see Monitoring Group, 2017 and Gibson Dunn, 2018), unlike in other contexts (e.g., see Kelly, Morgan, Ellis, Younger, Huntley, and Swann, 2010). In a sign that this state of affairs may be changing, the Monitoring Group's (2017) review of the IAASB included observations about the need for audit standards to be clearly evidence based.

Evidence-Based Policymaking

Our analysis of knowledge codification literature leads us to investigate attempts to transfer knowledge from the academic research community to policymakers in other settings (Campbell Collaboration, 2015, Miliani, 2005, Rousseau, 2012) that we then learned were based on the approaches developed in EBM (e.g., Reay, Berta, and Kohn, 2009; Gambrill, 2006). Thus, we examine the research on the effectiveness and efficiency of EBM knowledge transfer, specifically the process of translating knowledge into best practice guidelines (e.g., Scott and Guyatt, 2014). We continue the expositional approach from the previous section of interweaving conceptual analysis with application to the audit policymaking setting.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Academic medicine in the late 1980s was dealing with information overload (Eppler and Mengis, 2004), with hundreds of new studies being produced every month, and the notional half day a week for medical practitioners to stay up to date with the “literature” was seen as inadequate (e.g., Sackett et al., 1996; Sackett, 2000). As Eddy (2005) documents, changes to ineffective medical practices, guidelines and standard operating procedures, even after being identified in replicated research studies, took decades to move from the lab into practice (Dutton, 1988). Research suggests that, prior to the impact of the EBM movement, most guidelines for diagnosis and treatment in health care drew on three resources: panels of “expert” practitioners who opined based on their experiences, medical textbooks, and attempts to apply individual basic research articles directly to clinical settings (Eddy, 2005).

The EBM movement involves multiple facets (McQuay, 2011; Lambert, 2006; Eddy, 2005) but we focus on the EBM literature on developing evidence-based “best practice” guidelines and standard operating procedures (e.g., Scott and Guyatt, 2014).7 This area of EBM research carefully examines how guidelines can be developed that are well-informed from research evidence, while accepting that such research cannot speak for itself and must be translated into understandable and implementable guidance (e.g., Straus, Tetroe, and Graham, 2009; Timmermans and Mauck, 2005; Légaré et al., 2011; Littlejohns, 2001). Indeed, an extensive set of EBM research literature evaluates the success of this knowledge transfer and integration in the practices and procedures guideline development (e.g., Schünemann et al., 2014).

The EBM literature explores how various sources of evidence are employed in creating best practice guidelines and standard operating procedures at the national level (e.g., NICE in the United Kingdom, as in Atkins, Smith, Kelly, and Michie, 2013) and international level (e.g., the WHO, as in Alexander et al., 2016). This literature notes that locally based entities (hospital committees, local boards of health, subspecialty medical groups, etc.) will likely adapt these guidelines to their specific settings (see Scott and Guyatt, 2014 and Dizon, Machingaidze, and Grimmer, 2016 for discussions about trade-offs between adoption, adaption or contextualization of guidelines developed by other bodies). In all cases, the EBM approach explicitly requires that guidance to be informed by (or “based on”) the “best available” knowledge (Eddy, 2005; Scott and Guyatt, 2014).

Auditing policymaking application: Some might argue that transferring ideas from EBM guideline development to auditing policymaking is a stretch. We suggest that the perceived differences are because of lack of surface similarity (Holyoak and Koh, 1987) between the domains of medicine and auditing. Psychology research on analogical reasoning shows that those surface differences make it more difficult to identify the potential for knowledge transfer (Loewenstein, Thompson, and Gentner, 1999). However, psychology research also shows that locating deep structural analogs results in considerable benefits for knowledge transfer and learning (Novick, 1988; Tsoukas, 1993; Gentner, Loewenstein, and Thompson, 2003).

We argue that the current state of affairs in auditing policymaking is analogous to the state of affairs in medicine at the time the EBM movement started. Audit policymakers are mainly from the practitioner community, both internationally (at the IAASB) and nationally (e.g., the Canadian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board).8 These practitioners draw on their direct experience and the expert experiences of other practitioners on their standard development task forces in drafting auditing standards. The main inputs in the evaluation and evolution of the standard's drafts come from other practitioners via the comment letter process that tends to engage overwhelmingly accounting firms and practitioners (Tandy and Wilburn, 1992; Kwok and Sharp, 2005). Ongoing debate occurs as to how much customization of a standard needs to be done to suit local conditions in a manner very similar to that encountered in EBM guidelines.

EBM Knowledge Translation

EBM knowledge translation requires “a systematic review of all pertinent evidence (not just the evidence that supported a particular position), a critical analysis of the quality of the evidence, a synthesis of the evidence, a balancing of benefits and harms, an assessment of feasibility and practicality, a clear statement of the recommendation, and a detailed rationale” (Eddy, 2005:12). Table 2 documents key elements of the guideline development process developed by the UK's National Institute of Health and Clinical Evidence (NICE) that have been applied to the domain of public health.9 These elements are very similar to those used by the U.S. National Academy of Science's Institute of Medicine and the umbrella international practice guidelines organization, the Guidelines International Network (Kredo, Machingaidze, Louw, Young, and Grimmer, 2016). Steps 1 through 7 in Table 2 trace the guideline development process from project inception (identification of a need for a guideline) to completion (the publishing of an approved guideline).10

|

- * Adapted from Kelly et al. (2010).

We use the public health practice guidelines as an example because, unlike clinical practices in medicine (e.g., effectiveness of diagnostic tests, drug effectiveness), public health guidelines cannot be based solely on randomized clinical trials (RCT) or what accounting researchers would call controlled experiments (e.g., Kelly et al., 2010: 1058).11 Public health evidence explicitly includes observational, archival, and case study (or qualitative) research, in addition to experimental research.12 Further, given the diverse nature of public health interventions, the guideline development process needs to include practitioner concerns, population concerns, and other sources of qualitative and quantitative evidence, including expert opinion and commentary that may not come from formal research studies (Glasgow and Emens, 2007). Furthermore, it is clear that in this setting, the research evidence by itself cannot directly lead to setting policy, but it can inform policymaking.

Auditing policymaking application: Table 3 compares the steps in the due process of NICE guideline development in Table 2 to the IAASB auditing standard-setting process in Table 1. There are two key differences in the process undertaken in developing public health practice guidelines versus the IAASB auditing standards.

| NICE (from Table 2 ) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAASB (from Table 1) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 Project proposal based on work plan | X | ? | |||||

| 2 Steering committee approval | X | ||||||

| 3 Proposal discussed open meeting by full IAASB | X | ? | X | ||||

| 4 Project task force develops exposure draft | ? | X | |||||

| 5 Exposure draft exposed for comment | ? | X | ? | ||||

| 6 Final standard approved by IAASB | X | ||||||

- NICE (from Table 2).

- The scope of the project is determined.

- The scope of the project is exposed to the broader public health community so that the scope of the project is appropriately defined including specific researchable questions.

- The research evidence is gathered that addresses each of the specific researchable questions that are included in the scope of the project.

- An independent advisory group made up of various stakeholders develop the proposed recommendations based on the evidence synthesis and their direct knowledge and experience with the project questions.

- The draft recommendations go through an exposure draft period to stakeholders for input to the advisory group.

- The draft recommendations are tested in the field.

- The advisory group considers the comments from stakeholders and the results of the field testing in drawing up the final guidance.

The focal difference central to our analysis is Step 3 in the NICE guideline development process, which contains detailed protocols for developing research syntheses that focus on specific research questions determined in the guideline's project scope. In contrast, the IAASB standard-setting process has only vague references to “research” being undertaken at various stages in its process (marked with “?” in Table 3, Step 3 for NICE). According to our interviews with the past senior officials of the IAASB, the “research” they refer to tends to involve gathering opinions/practices from large public accounting firms, examining what national standard setters have mandated in the past or concurrently, and similar “research” approaches. These officials also report that professional accountants (the majority of the IAASB staff) carry out searches of the academic literature. Our discussions with former IAASB staff indicate that the goal of such searches is to identify academic research that is directly on point to the standard-setting topic (e.g., for research to be relevant to group audits, the substantive topic in the research must be group audits). In addition, under the NICE process, the research synthesis authors are routinely available to the guideline development advisory group to assist with understanding and evaluating the results of research evidence.13

Eddy (2005) describes a set of underlying institutional and other supports that developed with EBM practices to enable evidence-based guidelines. Eddy noted that these included identifying new or repurposing existing institutions and practices to support such guideline development. Table 4 summarizes our observations about those items that Eddy (2005) identified as key EBM guideline supports.

|

- * Adapted from Eddy (2005).

Development of Research Syntheses

Research on how EBM has been put into practice cites the importance of defining a specific answerable research question (Table 4, item (1) and the process used to determine the nature and extent of the evidence that is used to answer the question (Table 4, items 2–4) (e.g., Légaré et al., 2011). The standard or guideline development group needs to collaborate with the research experts (the synthesis authors who will carry out the systematic review) to develop specific questions that the standard setter needs answers to (Hollon, Areán, Craske, Crawford, Kivlahan, Magnavita, Ollendick, Sexton, Spring, Bufka, Galper, and Kurtzman, 2014). This question specification requires an interactive process of creating an understanding on the guideline development group's side of the nature of the evidence that is likely to be available, as well as clarifying for the synthesis authors what the research question(s) mean in relationship to likely available evidence. The questions need to be formulated in terms of the traditional four W's (who, what, when, where) and how focused on a specific substantive topic (Sackett, 2000). This specific researchable question underlies the evidence acquisition process and is iteratively reviewed by researchers and policymakers as the project continues. In other words, the synthesis authors and the guideline developers interact in a relationship that continues until the guideline is drafted, and potentially beyond.

- It may precede the development of an individual study's hypotheses (hence, it is highly biased towards justifying the author's hypotheses (Petticrew and Roberts, 2006: 3–4)).

- it may exist as a standalone qualitative assessment of the research literature, often by an author with considerable expertise in the area or a student who is entering an area of doctoral study.14

| Stage | Literature review | Research syntheses |

|---|---|---|

| Defining the focal question | General goal to review all literature on a particular substantive topic of interest | Clearly defined and well-focused question that academic research can likely provide a specific answer to |

| Developing and writing a protocol to do review | Author determines scope | Required. Developed with the advice of a practice-based committee that helps the researchers refine and understand what is the exact question to be answered |

| Methodology |

|

Follows explicit process to ensure scope of coverage that will allow answer to question. May be done in conjunction with practice-based advisory committee to ensure that methods will be understood. |

| Searching for studies |

|

|

| Definition of studies inclusion and exclusion criteria | Implicit by the author or a short description qualitatively |

|

| Screening of papers via titles and abstracts | Informal process by author and research assistants | Systematic screening and selection Usually cross-checked (at least on a test basis) by an independent coder |

| Quality assessment of studies | Implicitly by author | Explicit criteria specified |

| Research studies' conclusions documented | Yes | Yes |

| Analysis and synthesis | Implicitly by author leading to a written narrative review | Can be formal as in a meta-analysis or can be qualitative |

- * Adapted from Table 1.2 of Dickson, Cherry, and Boland (2014).

Table 5 is adapted from Dickson et al.'s (2014) Table 1.2. Table 5 elaborates on the differences between the traditional literature review and a research synthesis. Table 5's “Research syntheses” column shows how Table 4 is put into practice, starting with the development of a well-designed research question. Several excellent methodological resources and practical implementation guides exist to aid authors in developing a research synthesis (e.g., Petticrew and Roberts, 2006; Boland, Cherry, and Diskson, 2014).15

Ebm Knowledge Translation Practices Applied to the Group Audit Standard-Setting Project

To provide a concrete example for understanding the difference between a research synthesis and traditional academic literature, we provide a brief example of how a research synthesis might have been deployed in audit standard setting. Our example is based on research we have in progress (Hoang, Luo, and Salterio, 2018) on the development of the group audit standard (ISA 600) by the IAASB over the period 2002–2007 as part of the clarity project (see http://www.iaasb.org/clarity-center).

The IAASB's group audit project began in 2002 with the formation of a project task force (IAASB, 2007). The reason for formation of the task force was that “several bodies have requested requirements and guidance on the audit of group financial statements (‘group audits’), including the European Commission, the International Organization of Securities Commissions, the former Panel on Audit Effectiveness in the United States, and the International Forum on Accountancy Development” (IAASB, 2007). The goal of the process was to revise ISA 600 in light of the concerns expressed.16 At the IAASB meeting in South Africa (IAASB, 2002a), the IAASB made a tentative decision that the existing practice of allowing the option for a division of responsibility in the consolidated financial statements audits between the auditor of the overall consolidated financial statements and the auditor of a component (or subsidiary) included in those statements would be permitted to continue. As the minutes note: “As a result of the legal frameworks of certain countries, it was agreed that the division of responsibility provision in the existing ISA 600 should be retained” (IAASB, 2002a). This decision was reconfirmed without discussion at the next meeting (IAASB, 2002b) and again with limited debate at the following meeting (IAASB, 2003a).

Although not originally planned for discussion, IOSCO raised division of responsibility at a meeting of representatives of the IAASB and IOSCO Audit Working Party held on June 30, 2003. IOSCO indicated that they considered sole vs. division or responsibility as an important matter to be resolved by the IAASB, and was of the opinion that the IAASB should not provide for current practice, but for the best quality approach in the proposed revised ISA 600. IOSCO also indicated that it would be disappointed if the IAASB provided for both alternatives, and strongly urged the IAASB to decide on one approach. (IAASB, 2003b)

At the July meeting of the IAASB (2003c), one of the board members (not identified in the minutes) asked, “It is not clear why one approach is considered better than the other, which is what is implied by the term ‘desirable.’ Does the one approach render a better outcome (audit)?” (IAASB, 2003c). This question was not answered, as far as we can tell, in the publicly available IAASB material we have reviewed. Table 6 outlines how a research synthesis could be developed to specifically answer, from an academic research perspective, the board member's question. Table 6 also contains a summary of the steps that need to be undertaken to arrive at plan for searching the academic literature for evidence that could answer this question.

| Stage | Approach for research synthesis |

|---|---|

| Defining the focal question — clearly defined and well-focused question | Is a group audit where the group auditor takes sole responsibility in the audit report for all component audits likely to be more, less, or equally effective as when there is divided responsibility in the audit report between the group and component auditor? |

| Developing and writing a protocol to do review with the advice of a practice based committee so the researchers understand the exact question the standard setters want an answer to. |

|

| Methodology — ensure that the scope of the literature synthesis will allow the question to be answered and ensure practice-based committee is in agreement |

The research question can be structured as search for the likely effects on sole versus divided responsibility on audit effectiveness of two types of accountability pressure

|

| Searching for studies — a plan is developed that exhaustively searches the research literature to answer the question posed as translated and agreed upon by the researchers and the practice committee | In answering this question, the researcher would search exhaustively for organizational, psychological, and auditing research about the effects of specific versus broad based accountability on the judgments and decision of those that are being held accountable. |

We believe that a careful research synthesis focusing on this well-specified question would have produced a clear evidence-based answer in 2003 as to whether sole versus divided responsibility audit opinions would lead to “better outcomes.” In research currently in progress, Hoang et al. (2018) are testing this conjecture via a simulation of a knowledge transfer exercise with former audit standard setters and staff involvement.

Conclusion

- the presentation of research papers in unfamiliar form to policymakers prevents them from being used directly by the policy makers (Zander and Kogut, 1995);

- the absence of overlapping tacit knowledge between policymakers and academic researchers (Nonaka, 1994) prevents policymakers from being able to utilize research evidence; and

- the complexity of academic research warrants additional resources from the standard setters and more direct contact between the academics and standards setters (Szulanski, 2000).

We argue that the current auditing policymaking environment is analogous to the state of affairs at the start of the EBM movement with large amounts of research being produced but a very slow and inefficient transfer of knowledge occurring between the academic and policymaking communities. Hence, we examine the EBM literature on creation of guidelines to identify what has succeeded in facilitating academic evidence knowledge transfer (Scott and Guyatt, 2014). We carefully examine the tools used in EBM guideline development process (e.g., NICE 2009). We compare and contrast those practices with the current IAASB standard-setting process.

Our analysis indicates that key differences exist between EBM practices and processes on how to incorporate research and other sources of evidence into the guideline development from those attempted in audit policymaking (for elaboration see Salterio et al., 2018). In particular, in EBM guideline creation the communication of knowledge from academic evidence to policymakers requires an iterative process of well-specified question development followed by critical evaluation of the best available evidence. Further, the EBM process requires there to be ongoing involvement between the policymakers and researchers so that deep understanding of underlying tacit knowledge about research and standard setting is fostered. We propose that production of academic-authored research syntheses, prepared in accordance with the specifications in Tables 4 and 5, would be an effective strategy to address the current barriers to knowledge transfer from academic auditing research evidence to audit policymaking. We provide an example of how such a process could work in the audit policymaking context by examining the IAASB's group audit project.

We conclude by emphasizing again that evidence-based policymaking views research knowledge transferred as one input into the guideline development process. In other words, just as in the public health policymaking context, we do not expect that research syntheses of academic evidence will provide “the answers” to all the issues that face the auditing policymaker. Indeed, even if the research suggests approaches that appear to be effective, as we noted in our examination of the knowledge codification process, such knowledge needs to be incorporated into existing standards in a way that combines with the tacit knowledge of practitioners. Our proposal is to establish institutions and strategies for evidence-informed standard setting to be used in auditing, and for it to be deployed to develop the best auditing standards.