Current Trends within Social and Environmental Accounting Research: A Literature Review†

Accepted by Pascale Lapointe-Antunes. Charles Cho acknowledges the financial support provided by the Erivan K. Haub Chair in Business & Sustainability and the Global Research Network program through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2016S1A2A2912421).

Abstract

enGiven the recent rise in the evolution and maturity of social and environmental accounting (SEA) research and scholarship, we provide a literature review of the current trends within this area in a concise and harmonized manner for a wider audience in academia and practice. More specifically, we visit the current state of scholarly work, which can be useful in facilitating future research questions and further development of SEA research associated with relations between corporate social performance (CSP), corporate social disclosure (CSD), and corporate financial performance (CFP). Our goal is to offer insights to the current state of SEA research that is informative to both novice and expert SEA scholars, with the hope to promote and stimulate further advancement of research in this particular area. Drawing knowledge from relevant disciplines such as accounting, management, finance, and economics, this article visits the current trends within SEA research in terms of definition, research topics, theoretical viewpoints, methodological approaches, as well as suggestions for future research.

Abstract

frTendances actuelles de la recherche en comptabilité sociale et environnementale : recensement des écrits

Résumé

Compte tenu de l’évolution à la hausse qu'a récemment connue la recherche en comptabilité sociale et environnementale (CSE), du degré de maturité auquel elle est parvenue ainsi que du financement qui lui est accordé, les auteurs recensent les écrits afin de dresser un tableau concis et structuré des tendances actuelles dans ce domaine, à l'intention d'un public plus large chez ceux qui enseignent et exercent la profession. Ils se penchent plus précisément sur l’état actuel des travaux de recherche susceptibles de contribuer à l'analyse des sujets d’étude futurs et aux progrès de la recherche en CSE dans le champ des relations entre la performance sociale de l'entreprise, les informations sociales communiquées par l'entreprise et la performance financière de l'entreprise. Les auteurs visent à donner aux chercheurs en CSE, tant novices qu'experts, un aperçu de l’état actuel de la recherche dans le but de promouvoir et de stimuler l'avancement des travaux dans ce domaine particulier. En s'inspirant de disciplines pertinentes telles que la comptabilité, la gestion, la finance et l’économique, ils analysent les tendances courantes de la recherche en CSE en ce qui a trait à la définition de la sphère, aux sujets de recherche, aux points de vue théoriques, aux approches méthodologiques ainsi qu'aux pistes de recherche.

The notion of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been in existence for a relatively long time, but the most noticeable developments have occurred in the past 20 years. As society became more aware of environmental and social issues such as global warming, endangered wildlife, and sweatshops, we observed changes in the role of corporations and a significant increase in “social responsibility” and “sustainability” at the organizational level, engaging in a partnership with societal stakeholders (Blowfield and Murray, 2011: 117–23). The ethical principle of CSR touches upon various parts of a business. According to Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (2011), CSR assists in “supporting operational efficiency gains; improved risk management; favourable relations with the investment community and improved access to capital; enhanced employee relations; stronger relationships with communities and an enhanced license to operate; and improved reputation and branding.”

As in the traditional business model, accounting plays an important role in CSR and its development. Specific to the accounting field and profession, some of those advancements include the issuance of the first Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines in 2000 (GRI, 2015), and the initiation and expansion of services offered by accounting firms regarding climate change and sustainability services (Garforth, 2010). The area of social and environmental accounting (SEA) encompasses various branches of research — management accounting research for social and environmental issues; accounting for sustainable development; accounting for human rights and biodiversity; social accountability; relations between corporate social performance (CSP), corporate social disclosure (CSD), and corporate financial performance (CFP). Given the popularity and maturity of the academic research involving the latter research sub-theme, we provide a literature review of this specific branch of “SEA research”1 for a wider audience, ranging from novice to expert SEA scholars. In particular, we examine the current state of scholarly work which can be useful in facilitating future research questions and further development of SEA research associated with relations between CSP, CSD, and CFP.

Nowadays, corporate sustainability and CSR constitute an integral part of modern day business and their importance have become undeniable. This is partly illustrated by the issuance of annual stand-alone sustainability or CSR reports by the majority of large and influential corporations today, in addition to their annual reports and financial statements (KPMG, 2015). A content analysis of the top 100 U.S. retailers’ corporate websites revealed that most companies had CSR integrated into their mission statement or had a separate statement for CSR (Lee and Fairhurst, 2009). Investors can monitor sustainability performance of a given company through the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI) or The Financial Time Stock Exchange's FTSE4Good, and there are several portfolios of socially responsible investments (SRI) actively traded in the market. According to the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment (2016), SRI in the U.S. totaled 8.72 trillion U.S. dollars at the start of 2016, which represents a 14-fold increase since 1995.

The emergence of CSR as a key societal concern and the costs borne by firms that deceive their stakeholders on CSR-related issues can be illustrated with the two following cases. First, a photo of a young boy sewing a Nike football triggered intense publicity in the late 1990s (Wazir, 2001). However, the Nike scandal involving sweatshop workers in southeast Asian factories did not have a severe impact on the company's financial position at the time. The decrease in financial and market performance in the late 1990s was blamed on the Asian financial crisis, and despite speculations, there was no empirical evidence that the decline in financial performance was directly associated with the mistreatment of factory workers (BBC News, 2000; Boje, 2000; Mocciaro Li Destri, 2014: 125–26). Nonetheless, Nike was heavily criticized by the public, and the company had to exert great effort to ensure that the wage issues in their overseas factories were rectified (Cushman, 1998; Nisen, 2013). Twenty years later, when the well-known automotive company Volkswagen violated the Clean Air Act in 2015, its stock price plunged almost 30 percent in a matter of days as a direct consequence (La Monica, 2015). While the speed of information has improved drastically since the 1990s through advancements in technology, CSR is no longer solely an issue of bad publicity — there are now financial consequences clearly linked to CSR activities.

As illustrated in the anecdotal evidence above, CSR evolved into a crucial part of conducting a business, and as a response to the rising interest (and concerns) from society for environmental and social issues, the number of academic research published on the topic increased exponentially. Historically speaking, the first round of breakthrough in CSR research development occurred in 1970 when Committee for Economic Development conducted an original study on CSR (Lee, 2008). Nevertheless, the notion of ethical and social obligations of business entities had become known much earlier (Bowen, 1953). But while the initial research by Bowen (1953) recognized the existence of the ethical and social responsibilities of a corporation, it remained relatively abstract and with some level of uncertainty around the concept. The attempt to link firm performance with CSR started in the 1970s, and since then, CSR and its relationship to financial performance and economic consequences has progressed into an emerging area of research over time.

Scope of the Literature Reviewed

Following the literature review continuum proposed by Massaro, Dumay, and James (2016), we implemented some rules to define the scope and purpose of this article. First, with the recent rise (and “rediscovery”) of CSR in “mainstream” accounting research (Cho and Patten, 2013; Roberts, 2018), the main aspects discussed in this article are limited to the relations among CSP, CSD, and CFP in publicly traded companies. We argue that it is reasonable to confine the scope of review to those large public corporations, as they initiated the disclosure and societal awareness of CSR activities and performance (Buhr and Gray, 2014). Partly based on the methods suggested by Massaro et al. (2016), we searched for a mixture of keywords presented below on Google Scholar.2

Not so long ago, SEA research was considered to belong outside the so-called “mainstream” domain or “major area” of accounting research. However, the recent explosion of socially and environmentally responsible awards, certifications, investments, and portfolio indices has recently caught the attention of financial market researchers. Furthermore, during that time — when corporate sustainability amalgamated into a component of every firm's business model — SEA research also started to capture the interest of a broader group of academics. To illustrate, a keyword search of various terms including, yet not limited to, “CSR,” “corporate social responsibility,” “sustainability,” “environmental accounting,” and “CSR disclosure” in journals affiliated with the American Accounting Association (AAA) (see Appendix) published between 2000 and 2017 generated approximately 30–280 matches, albeit with many duplicate results — and we noted that the majority of the publications occurred in the current decade. For instance, the keyword “sustainability” resulted in 279 articles, with 208 of them published after the year 2010. We concede that these numbers represent a small portion of the SEA research universe as tens of thousands of matches were found using more specific phrases such as “sustainability + accounting,” and “corporate social responsibility + accounting” on Google Scholar; however, we also argue that this represents a significant development considering that the same set of keywords resulted in less than 10 matches in total between 1970 and 1999 for the same group of journals affiliated with the AAA. Moreover, despite the increased attention from the mainstream accounting researchers, their scope of the CSR literature appears to be (much) narrower than the reality of the SEA field. For instance, the articles in The Accounting Review's 2012 Special Forum on CSR research in accounting omitted a vast number of references to existing scholarly work in SEA, and also seemed to be unaware of the existing SEA research journals other than “theirs” (Cho and Patten, 2013; Roberts, 2018).

Given this awkwardness in SEA research and scholarship, as well as the evolution and maturity of this topic, we provide a literature review of SEA research related to CSP, CSD, and CFP, in a concise and harmonized manner for a wider audience in academia and practice. The so-called “mainstream” research mainly involves publicly available archival financial data for quantitative analyses, and research questions regarding these tri-factors are prevalent. In order to narrow the gap and to encourage communications between the two research communities, we chose some of the most common topics in SEA.

Second, we review articles published between 2000 and 2017, inclusively. As previously mentioned, the most noticeable developments in CSR occurred in the past 20 years or so. Since this article focuses on the relations between CSP, CSD, and CFP in public companies, we set the starting point of the literature covered immediately around the period where the GRI, DJSI, and FTSE4Good were launched as these initiatives are largely relevant in this subdivision of SEA research. In addition, we are aware of several literature reviews on SEA research. For example, Huang and Watson (2015) review CSR research published in accounting journals, but only cover articles from the top 13 accounting journals in the recent decade. Gray and Laughlin (2012) focus on a critical review of SEA research. Some literature reviews focus on certain areas within CSR research, such as CSR assurance (Simnett and Vanstraelen, 2009), environmental disclosure (Berthelot and Cormier, 2003), and social and environmental reporting (Gray and Kouhy, 1995). Our article aims to complement the existing literature reviews to contribute to the body of knowledge in the field without being repetitive. Its objective is to offer insights to the current state of SEA research that is informative to both novice and expert SEA scholars, with the hope to promote and stimulate further advancement of research in this particular area. To this end, and because it is increasingly common to see SEA academics cross publish their works in multiple disciplines, we expand the scope of journals covered by embracing a variety of journals in accounting, and by drawing knowledge from other related disciplines in business such as management, finance, and economics. In order to be harmonious yet concise, we include some seminal papers by the veterans, and “standing on the shoulders of giants” (Massaro et al., 2016), we gather additional scholarly works that cite or base their foundation on such research, to provide insights to the current trends in a cohesive manner. Whenever possible, findings from multiple perspectives are discussed to illustrate a theoretical tension, and to achieve comprehensiveness. The number of citations was the main guideline for identifying “giants” in the groups of literature examined. Ideally, the search results should be sorted by the number of times an article was cited. However, Google Scholar makes it only possible to sort the search results by either relevance of the keywords used for a particular inquiry, or by dates published.3 It is worth noting that the number of times an article is cited also depends on the exposure of the journal (i.e., impact factor), seniority or fame of the author(s), and the date published. Therefore, we had to exercise a certain degree of professional judgment when identifying the articles reviewed. Once a well-known paper was identified and reviewed, we were able to view other publications citing the article (this information is available by clicking a “Cited by” link provided on Google Scholar results, or following a customized link provided by the journal's website). The title and abstract of those articles were then scanned, and subsequently examined based on the relevance to this literature review. In total, 137 papers from academic and practitioners’ journals, 17 websites and news articles, 10 books and book chapters, a conference paper, and a working paper were reviewed for this paper. While do not claim the literature reviewed in this article to be exhaustive, we do attempt to provide a systematic view of the focused area of SEA, by not limiting the journal titles.

The rest of this article will (re)visit the current trends in SEA research in terms of definition, research topics, tensions between competing theoretical viewpoints, methodologies applied in SEA research, as well as suggestions for future research.

Trends in CSR Research

Much of SEA research pertained to deciphering relations between financial performance and environmental and/or social dynamics of a firm. This research stream involved exploring interactions and impacts among CSP, CSR disclosure, and financial performance of a company. The basic idea is that corporations are (or should be) generally concerned with how to account for the activities around CSR, as the public and regulators started to pay close attention to the issue. The Canadian government explicitly stresses that “management and mitigation of social and environmental risk factors are increasingly important for business success abroad, as the costs to companies of losing that social license, both in terms of share price and the bottom line, may be significant” (Global Affairs Canada, 2017). With the public awareness of social and environmental friendliness, firms must be more responsible in their actions in order to sustain themselves. This reflects the expedients stance — one of the seven perspectives described by Gray and Owen (1996) — where companies (should) have a long-term vision that economic welfare and stability can only be achieved with the acceptance of certain social responsibilities. However, accepting additional responsibilities can be costly, thus establishing a clear relation between social and financial performance has become vital factor in a firm's existence. Subsequently, managers will also have the desire to communicate their acceptance of such additional responsibilities and resulting social performance to gain credibility from the public, as part of corporate brand management and value creation (Middlemiss, 2003). Thus, a corporate social and environmental disclosure can potentially help investors and other market participants better assess companies’ future financial prospects and longevity, and act as complementary to their financial disclosure. Taken together, these fostered some of the most popular research questions in SEA, exploring relations between CSP and CFP, CSD and CSP, and CSD and CFP, in both directions of causality and various measurements for each factor.

CSP and financial indicators

As seen in the example of the Nike scandal, there was a lack of directly observable associations between CSP and CFP in the past. Consistent with this case, a worldwide study conducted by Ernst & Young in 2002 found that while 94 percent of the companies said that corporate sustainability strategy might produce better financial performance, only 11 percent of firms were implementing it. This indicates that for corporations to implement CSR, a very clear association must be present and move from the word “might” to “does.” Correspondingly, the association and causality of CSP and financial performance relationship cultivated extensive debates starting from the early days of CSR research. When it comes to causality, the debate goes back to the eternal issue of endogeneity — do more socially responsible firms perform better financially, or are the firms more socially responsible because they are performing financially well?

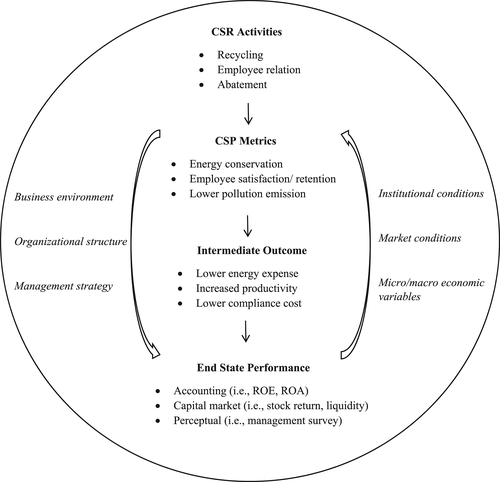

Figure 1 provides a visual snapshot of the dynamics discussed above — it introduces the notion of intermediate outcome in an attempt to establish finer relations between CSP and CFP, which may be useful for future research. Schneider (2015) proposed that reflexivity in sustainability accounting and management can uncover the realization of business models assimilating economic, environmental, and social matters. Reflecting on the notion of “virtuous circle” by Nelling and Webb (2009), the association between CSP and financial performance is not unidirectional but a continuous loop, affected by a mixture of endogenous and exogenous factors partaking either a mediating or moderating role. The expanded list of mediating and moderating elements of a firm's CSR activities include size, level of diversification, R&D, advertising, government sales, consumer income, labor market condition, industry life cycle, state of overall economic condition, degree of competition, and various institutional conditions (McWilliams and Siegel, 2000). Whether the factors in the outer circle are moderating or mediating still need to be tested, and the interaction between the CSR activities and financial performance will also need to be examined at each of the stages in the loop. Wagner, Nguyen, and Azomahou (2002) tested a simultaneous relationship between CSP and CFP, and Fauzi and Mahoney (2007), as well as Orlitzky and Schmidt (2003) suggested that business environment variables, management strategy, organization structure, and management control system moderate the causal relation between financial performance and CSP.

An integration of various frameworks reviewed

On the other hand, the answer to the question of whether CSP and CFP are correlated is more obvious. Between 1972 and 2000, 85 out of 90 published papers found that CSP predicts or helps determine financial performance (Margolis and Walsh, 2001), indicative of a correlation between the two constructs. Yet, the nature of relationship between CSP and financial performance was controversial and remained unsettled for some time. The net effect of environmental investments and return can be positive (Clarkson, Li, and Richardson, 2011; Moneva and Ortas, 2010; Nakao, Amano, Matsumura, and Genba, 2007), negative (Makni and Francoeur, 2009; Wagner et al., 2002), or neutral (Aragon-Correa and Rubio-Lopez, 2007; Filbeck and Gorman, 2004). To explain this mixed empirical evidence, there are a few conflicting arguments to support different outcomes. Some stated that managers who are socially aware have superior skills to manage their companies overall, thus achieving better financial performance (Alexander and Buchholz, 1978). The counter argument was that those firms that are socially responsible have a competitive disadvantage because of the added costs, from a shareholder perspective (Vance, 1975). The third explanation is the efficient market hypothesis that favours immediate incorporation of new information, therefore making any positive or negative effects of CSP neutral when using stock market performance as the measure of financial performance (Fama, 1970; Alexander and Buchholz, 1978).

Regardless of the exact direction of this association, there is overwhelming evidence that documents the association between CSP and CFP and this research evolved to investigate that link in a more precise manner. In the academic literature, Peloza (2009) reported that 59 percent of studies found a positive association between CSP and CFP, while 14 percent found a negative one, and the rest of the research had neutral or mixed results. The general distribution among positive, negative, and neutral associations was similar in other meta-analyses, favoring a positive correlation (Horváthová, 2010; Orlitzky and Schmidt, 2003). Presently, the traditional view of inevitable tradeoff between CSP and CFP (Friedman, 1970) is no longer explicitly tested, and a vast majority of articles prefer to utilize frameworks that support a synergetic, “win-win” strategic outcome (McWilliams and Siegel, 2011; Orlitzky and Schmidt, 2003; Wagner and Schaltegger, 2004). On the other hand, in a recent investigation of how firms treat different stakeholder groups, Kumar and Boesso (2016) find that when companies fail to meet the expectations of their primary or secondary stakeholder(s), they are penalized with poor financial performance. They exhibit that a “lose-lose” situation also exists, complementing the previously documented “win-win” strategic outcome. Their results are consistent with the earlier anecdotal illustrations, where the companies suffer negative financial consequences due to poor CSP.

Recently, CSP-CFP research has broadened its scope beyond a simple investigation of CSR ranking or scores and financial profit. Huang and Sun (2017) show that organizations with higher CSP are less likely to take risky tax strategy compared to those with poor CSP. Similarly, Zeng (2016) examines the relation between CSR, tax aggressiveness, and market value of the firm, and finds that firms with higher CSR rankings are less likely to engage in tax aggressiveness, and that firms with better CSR reputation have higher market values. Similar results have been documented between the level of CSR disclosure and tax aggressiveness (Lanis and Richardson, 2012). Others have linked corporate tax rate and tax-lobbying expenditure with CSR by investigating whether paying corporate tax is viewed as socially responsible (Davis, Guenther, Krull, and Williams, 2013).

In capital markets, short sellers consider environmental, social, and governance (ESG) scores as value relevant in decision-making process by avoiding firms with high ESG scores and preferring firms with low ones (Jain and Jain, 2016). As short sellers’ objective is to sell high, then buy low, they expect the share price of poor ESG performing firms to decrease, which will make their stock trading strategy to be successful. El Ghoul, Guedhami, and Kwok (2011) find that companies with better CSR scores enjoy lower cost of equity in the U.S. and that the businesses affiliated with tobacco and nuclear power industries, which have lower CSR scores, incur higher cost of equity financing. Cost of capital is also related to environmental risk management — firms that manage these risks better have cheaper cost of capital (Sharfman and Fernando, 2008). In an event study, Wagner et al. (2002) learned that environmental events exhibit a causal relation with abnormal returns, and act as a signaling agent to the public. Their analysis over a range of manufacturing industries resulted in significant positive abnormal returns after positive environmental events and significant negative abnormal returns after negative environmental events.

CSD and performance

“You've heard it all before. Someone reviews a corporate social responsibility report and complains that there are too many pictures of rainbows and smiling children. There's not enough hard data. It's clearly a marketing piece. On the other hand, overly-analytical reports are described as “dense” and can be overwhelming to anyone but the report writer. You hear things like, I'm not a financial analyst, I'm just trying to understand if your company is “green” or not.” (Hausman, 2008)

While various questions related to CSR disclosure and reported firm performance have been investigated, the measurements were generally imperfect and the results were often contradictory. First, defining the users of the sustainability reports has been, and still remains, a difficult task because it encompasses a much broader spectrum of issues besides the economic consequences of the company's environmental and social actions. Second, the motivations for providing CSR disclosure have been debated — do companies disclose such information to signal their good or better performance, or is it more about covering up their poor performance? Furthermore, the voluntary nature of sustainability reporting, with no clear set of guidelines in the earlier days, contributed to the uncertainty about the usefulness and/or value-relevance of such information. With the exception of polluting industries, which are under legal obligation to disclose and report their environmental actions, CSR reporting remains voluntary in nature with unrestricted content of the reports. Not surprisingly, those reports were largely inconsistent and incomparable, and were subject to strong criticism of being inadequate for making any practical assessment (Gray, 2006). It appeared that the volume of voluntary environmental disclosure was associated with firms with poor environmental performance, and that disclosure was also a reactive measure for legitimization (Cowan and Deegan, 2011). As SEA research developed, there was a clear and undeniable need to improve and assess the quality of CSR disclosure. To answer the call for reporting guidelines, the GRI developed a sustainability reporting framework that is now most widely used around the world. The GRI proposes principles to define report content such as materiality, stakeholder inclusiveness, sustainability context, and completeness; and report quality such as balance, comparability, accuracy, timeliness, reliability, and clarity (GRI, 2015). Although the GRI guidelines have inherent limitations because it is simply impractical to measure and report a completely holistic picture of sustainability (Ballou, Heitger, Landes, and Adams, 2006), they still remain to be the most heavily used and relied upon reporting framework and guidelines.

As a firm accepts environmental and social responsibilities to economically sustain its business operations, CSR disclosures can complement financial disclosures, assisting investors in determining a firm's value and prospects. In this stream of research, disclosure of environmental information is the primary component of CSR. Using both samples from North America and Europe, Aerts and Cormier (2008) looked at the financial analysts’ ability to forecast earnings in association with corporate environmental disclosure. Results showed that higher quality of environmental disclosure translates into more precise earnings forecasts by the analysts. Even though the effect is somewhat reduced when it comes to pollution sensitive industries, this supports the notion that environmental disclosure complements financial disclosure. The findings hold in an international setting, where the issuance of stand-alone sustainability reports seems to be associated with less error in analyst forecasts (Dhaliwal, Radhakrishnan, and Tsang, 2012).

Bozzolan et al. (2015) documented that companies that actively engage in CSR are less likely to engage in real earnings management than in accrual earnings management, because real earnings management can be damaging to the firm's future performance. It appears that these companies perform better financially due to real economic performance instead of using gimmicks such as earnings management (Litt and Sharma, 2013). In a related line of research, Patten and Trompeter (2003) examined the level of pre-event environmental disclosure and the extent of earnings management in response to regulatory threat following a chemical leak in 1984. There were significant negative discretionary accruals for 1984, with less discretionary negative accruals incurred by the companies that filed greater pre-event environmental disclosure in 10K reports. These results imply that environmental disclosure is an effective tool for reducing exposure to potential regulatory costs, and that the earnings management strategy goes beyond the traditional variables. Christensen (2016) finds that firms with CSR reporting activities are less likely to engage in high-profile misconduct such as bribery, price fixing, and violation of human rights, but when they happen, the same firms are subject to less reduction in share price. Overall, CSR disclosure can be considered a risk management tool to reduce environmental, social, and reputational risk exposure (Bebbington and Larrinaga-Gonzalez, 2008a; Dhaliwal, Li, and Tsang, 2011).

Given that external audit is a way to increase the value-relevance of information disclosed through greater credibility (Pflugrath and Roebuck, 2011), an increasing number of studies examine sustainability report assurance. In the CSR literature, sustainability or environmental audit is viewed as assuring the accountability of corporations (Power, 1991, 1997). Sustainability assurance provides greater confidence to stakeholders about the quality of the organization's sustainability reporting; acts as a tool to mitigate against the risk of the release of potentially misleading or inaccurate information, and adds independent credibility to the performance data and other information disclosed in the report. Thus, sustainability report assurance is important to various statement users such as investors, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), activist groups, government, and communities because of the benefits discussed above (O'Dwyer, 2011). Providing assurance for sustainability reports is unique because it concerns more than the traditional information users who mainly care about the financial statements of a firm. Additionally, due to the various stakeholders involved, the main beneficiaries of sustainability reports assurance may not be limited to investors — yet they will bear the cost of this assurance service. Given the evidence of a generally positive association between CSP and CFP as stated in the previous section, if there is a positive relation between CSR disclosure quality and CSR performance (Al-Tuwaijri, Christensen, and Hughes, 2004; Clarkson, Overell, and Chapple, 2011; Clarkson, Li, and Richardson, 2008; Herbohn and Walker, 2014), there could be eventual benefits to shareholders for investing in CSR report assurance. However, this relation between CSR disclosure and CSP proved to be challenging to maintain. Some studies found no empirical significance between CSR disclosure and CSP (Freedman and Wasley, 1990; Wiseman, 1982) while others have discovered a negative relation (Cho, Freedman, and Patten, 2012; Cho, Guidry, and Hageman, 2012; Cho and Patten, 2007; Hughes and Sander, 2000).

In line with the above and as expected, evidence on the topic of sustainability assurance is also mixed. On one hand, a body of research finds that sustainability report assurance appears to be beneficial to firms. Environmental disclosure quality score is higher for those firms who received a third-party assurance for their reports compared to those who did not (Moroney and Windsor, 2012). Moreover, companies with their CSR reports assured have lower cost of capital and the effect is also subject to the assurance provider (Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez, 2017). Additionally, businesses looking to enhance the credibility of reports as well as improving their reputation have higher likelihood to have sustainability reports audited (Simnett and Vanstraelen, 2009).

On the other hand, however, Owen, Swift, and Humphrey (2000) conduct a series of interviews and express their skeptical (and critical) view that CSR reporting assurance is increasingly becoming a legitimizing tool for companies. Furthermore, Kuruppu and Milne's (2010) experimental study results in mixed outcomes of independent assurance's effect on credibility of the CSR reports for decision-making. Cho, Michelon, Patten, and Roberts (2015) document that CSR disclosure fails to be valued positively by investors, suggesting that the market does not always value CSR. These findings potentially imply that CSR report assurance may carry its own value for the firm, regardless of how investors consider CSR disclosure or reports itself. For example, there is a greater chance that a company will have their sustainability report assured if it is operating in a country that is more stakeholder-oriented and with a weaker legal enforcement. This suggests that voluntary assurance of non-financial information such as a firm's CSR report can act as a governance tool that can substitute for a country's legal enforcement regime (Kolk and Perego, 2010). Alternatively, Edgley and Jones (2010) document that assurance providers consider themselves as a “voice” for stakeholders, and the audit of CSR reports plays an important role in achieving greater stakeholder inclusion of the reports.

CSR in emerging economies

CSR in emerging economies is one of the recent trends in SEA research. Social problems in developing countries such as poverty, gender and racial inequalities, government corruption, war crimes, and human rights violation, are no news. With the advent of globalization, the role of emerging economies has increased significantly in the world's economy, and the function of business in those economies also has become more important. The discussion around corporate citizenship in developing economies gained popularity in the mid-2000s. Thus, reviewing the literature on CSR in developing markets is worthwhile when discussing the current state of CSR research. Depending on how one perceives CSR in emerging markets might dictate the type of inquiry and analysis in their research. Some argue that the broad notion of CSR in developing countries has been around for quite some time through their own contextualized roles of companies in society (Blowfield and Frynas, 2005). There is evidence supporting this view, showing that companies in emerging markets have different priorities of CSR elements than those in developed countries (Welford, 2004). Others believe that CSR in emerging markets are based on large businesses from the “North” (Fox, 2004). For instance, the CSR activities of companies in Mexico's auto parts industry have resemblance to those of developed countries (Muller and Kolk, 2009). In an alternative approach, business can be seen as having a direct relation to poverty in emerging countries, where it can play the role of victim (i.e., poor infrastructure, corrupt governance), cause (i.e., labor exploitation, pollution), or solution (i.e., microfinance, goods, and services for unserved markets) (Blowfield and Murray, 2011: 88). Blowfield and Murray (2011) also offer yet another perspective where corporations are bystanders of economic and social conditions in those countries, and their decision to operate in developing economies are purely based on traditional investment decision criteria. The new economies can represent an opportunity, such as low labor cost or taxes, or a barrier, such as weak infrastructure.

Although awareness of CSR in new economies is on the rise, developing countries are faced with barriers including weak institutions, standards, governments, and legal systems. While these problems are marginal in developed economies, such weak institutional environments can obstruct the advancement of CSR in emerging nations (Kemp, 2001). A series of interviews with companies in Lebanon uncovered that neither local organizations nor subsidiaries of multinational enterprises (MNE) had clear targets, metrics, or due diligence in their treatment of CSR (Jamali and Mirshak, 2007). Similarly, a case study of an Indian company found that it lacked a well-developed strategic method for CSR communication (Amaladoss and Manohar, 2011). Reimann, Ergott, and Kaufmann (2012) found that local mid-level employees of MNEs are influential in corporate social efforts in Asian, Eastern European, and Latin American countries, suggesting that encouraging employees is a possible way to progress CSR in MNE subsidiaries operating in emerging economies.

In terms of disclosure, evidence states that CSR reporting in emerging markets is more advanced than expected, and these markets often exhibit higher CSR reporting standards than some developed markets (Baskin, 2006). Likewise, Preuss and Barkemeyer (2011) analyzed CSR reporting schemes of developed, transition, and developing economies, and find that firms in emerging economies have better coverage of GRI indicators. They offer two possible explanations: either MNEs in developing countries are more concerned with CSR, or the companies are using GRI reporting as a greenwashing tool. Wanderley, Lucian, and Farache (2008) found that industry and country of origin impact CSR disclosure on the web, after analyzing 127 company websites from developing economies. Lattemann, Fetscherin, Alon, and Li (2009) compare CSR disclosures in China and India, and found that Indian companies have better CSR communication since they have a more rule-based governance system. In China, CSR reporting quality can lead to greater media and government endorsement, which leads to better financial performance (Dai, Du, Young, and Tang, 2016).

In stock markets, CSR announcements can also have a positive impact on stock performance, as an event study found that South African investors react positively to CSR announcements (Arya and Zhang, 2009). In 2013, a clothing factory building collapsed in Bangladesh causing more than 1,000 fatalities, and worker safety agreements were initiated for the textile MNEs to sign as a direct result. Paik and Lee (2017) documented that the firms who signed the agreements enjoy greater social visibility, past CSP, and impact on share price post-tragedy. They also found that the market positively responded to the announcement of a firm becoming a signatory of the agreements. While CSR in developing economies is relatively new and constitutes a small portion of CSR research, it will be interesting to see how this avenue of research matures, as it has a potential for some unique research opportunities.

Theoretical frameworks of CSR

The competing views of shareholder and stakeholder principles form the foundation for describing and understanding CSR. Milton Friedman (1970) stated that the responsibility of a corporation is to generate profits for its shareholders. Anything other than core business activities to increase shareholder value will deviate from this main responsibility — this is fundamentally embedded in capital market-oriented research. In this case, CSR is strictly a part of the profit-creating function of a firm, as it must be always beneficial for the shareholders. Companies should only care about profits and therefore their shareholders because it is simply inefficient for business to care about social issues. It is the government's job to address public and social concerns, and charitable donations and community services are personal and individualized to achieve maximum efficiency.

On the other hand, stakeholder principles argue that a firm's fiduciary duty extends beyond the shareholders, and companies need to take into considerations all stakeholders such as the environment, government, employees, and society. In other words, the contractual relationship between the principal and agent has changed over time, and the agent (i.e., the firm) is bound by a contractual relationship that involves more than one type of principal (i.e., the shareholders). Although some mischaracterize stakeholder theory as a concept that favors everyone else but the shareholders (Sundaram and Inkpen, 2004), Freeman and Wicks (2004) stress that the definition of stakeholders is in fact inclusive of shareholders. In a wide sense, stakeholders are those who can affect or be affected by the achievement of a business. Narrowly speaking, stakeholders are the ones upon which the corporation depends on for its survival (Freeman, 1984). However, even the narrow definition of stakeholders is vague since it can encompass an uncertain number of groups and individuals, and specifying the complete list of stakeholders may be impossible. Naturally, the conflict of interest among different stakeholders is inevitable. While stakeholder theory does not ignore the interests of shareholders, it dictates that an organization must balance between conflicting interests of multiple stakeholders, consisting of employees, community, environment, government, suppliers, consumers, and others, even if the shareholders’ stakes are compromised. Stakeholder theory quickly gained popularity in the 1990s with a momentum created by Clarkson (1995), Donaldson and Preston (1995), Jones (1995), and Roberts (1992) and remains to be an important underlying theory for research.

There are several theoretical frameworks applied in discussing CSP, CSR disclosure, and CFP relationships. A popular theory for explaining the CSP-CFP relationship is the resource-based view of the firm (Aragon-Correa and Sharma, 2003; Clarkson, Li, et al., 2011). Under this theory, not all firms will equally benefit from a proactive social and environmental strategy, and more financially resourceful firms with higher management skills will be the ones implementing a proactive social and environmental strategy (Christmann, 2000). Additionally, evidence suggests that information costs, financial condition, and firm size of a company are among various factors of environmental disclosure (Cormier and Magnan, 1999). On a related note, Porter's hypothesis can also extend to CSR research design. According to this perspective, superior social and environmental performance can represent a potential source for long run competitive advantage via an efficient process and productivity, lower costs of compliance, as well as new market opportunities (Porter and van der Linde, 1995). To illustrate, if a firm can reduce its waste of resources by innovation through environmental initiatives, it can offset the costs of compliance. This view of competitive advantage obtained by a socially responsible firm aligns with the traditional view of business. The resource-based view of the firm argues that companies with greater financial resources are better equipped to invest in more CSR activities, which results in better CSP. Since CSP is positively associated with a firm's financial performance, having the superior resources to spend on CSR ultimately leads to shareholder value creation (Aragon-Correa and Sharma, 2003; Clarkson, Li, et al., 2011; McWilliams and Siegel, 2011; Russo and Fouts, 1997). Also, the competitive advantage and innovation argument adopted from Porter's hypothesis also results in economic benefits of the shareholders. Moreover, many of the studies employ financial performance as the dependent variable in analyzing the relation between CSP and CFP, which means that they are mainly focused on what CSR and CSP can do for the firm's economic well-being.

McWilliams and Siegel (2011) propose that the true underlying motivations for CSR and desire for CSP are difficult to assess due to information asymmetry. They argue that it is unlikely for management to reveal the true motives for engaging in CSR, such as reducing costs, increasing revenue, and enhancing the firm's reputation because detaching CSR and CSP from the bottom line may appear more attractive to the general public. If this is the case, then perhaps the shareholder perspective is not completely wrong. The increasing evidence of a positive relation between CSP and CFP can simply be understood as follows: firms got better when aligning shareholders’ interests with the inevitable pressure from regulators and the public through strategy — but ultimately, their goal is to satisfy the shareholders.

In the CSR disclosure literature, one way to interpret a firm's voluntary CSR communication is through signaling theory. Firms may disclose costly information to signal performance (Hughes, 1986; Spence, 1978). From a signaling theory stance, a firm's environmental disclosure is likely to have greater quality of information that signals performance (Clarkson et al., 2008). As previously discussed, a positive association between the quality of CSR disclosure and CSP is supported by prior research (Al-Tuwaijri et al., 2004; Clarkson, Overell, et al., 2011; Herbohn and Walker, 2014; Mahoney, Thorne, and Cecil, 2013). Signaling effect also exists in emerging economies as practicing CSR is positively associated with financial performance (Su, Peng, and Tan, 2016). Also, companies might wish to send a stronger signal of CSP through increased quality (i.e., credibility) of communication medium (i.e., CSR report) through third party assurance, with added benefits such as lower cost of capital (Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez, 2017). On the contrary, there are studies that documented either no significant association between CSR disclosure and CSP (Freedman and Wasley, 1990; Wiseman, 1982), or a negative relationship (Cowan and Deegan, 2011; Cho and Patten, 2007; Cho, Guidry, et al., 2012; Patten, 2002; Hughes and Sander, 2000). Moreover, Michelon, Pilonato, and Ricceri (2015), in their analysis of CSR reporting practice and disclosure quality found that the practices of CSR reporting, assuring, and following the reporting guidelines appear to be symbolic in nature, and does not translate into higher information quality disclosed.

This leads to the discussion of legitimacy theory, which is perhaps the most applied framework in CSR disclosure literature (Gray and Kouhy, 1995; Cho, Laine, Roberts, and Rodrigue, 2015; Cho, Michelon, and Patten, 2012; Milne and Gray, 2007). Instead of signaling performance, firms may try to manage its image or legitimize themselves through voluntary disclosure. Logically, there is a trade-off between the costs and benefits to be derived from voluntary corporate disclosure, and some will argue that there is equilibrium that determines the optimal level of disclosure (Verrecchia, 2002). Due to the tension between information cost and benefit, there is an incentive for a firm to both disclose and withhold information. Managers may decide to withhold information to exploit economic advantage but they may also decide to disclose information to gain some economic advantage (Dye, 1985). According to legitimacy and impression management theory, corporations simply want to “appear” responsible for the social duties, and are selective in the type, level, and frequency of the CSR information disclosed. Carroll's (1979) hierarchy of corporate responsibilities proposes four levels of CSR, economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary, often illustrated in a pyramid form. In the eyes of legitimacy theory, companies will try to promote themselves as being on top of the pyramid, while their true actions are somewhat primitively motivated. For example, negative media coverage of a firm can act as a driver of environmental press releases (Aerts and Cormier, 2009). Although such practices of corporate legitimacy can be perceived as canny, it should be noted that the concept of impression management does not necessarily promote the idea of corporations lying to the public. Neu and Warsame (1998) state that the term “impression management” is used in “attempts to shape the impressions of relevant publics through the provision of environmental disclosures, but it says nothing about the “truth” or “falsity” of these disclosures” (Neu and Warsame, 1998: 272).

Many researchers support the notion of corporate legitimacy. In a case study, Adams (2004) notes that the company did not fully disclose their CSR performance. In her investigation, the company tried to paint a picture of a firm that performs well and continues to seek to improve in terms of CSR, providing a one-sided and biased view of the company's CSR practices. Cho, Freedman, et al. (2012) found that environmental capital spending is immaterial, hence the decision to disclose environmental capital expenditures is at the discretion of the firm. They also found that the choice to disclose environmental information is correlated with firms that have poor environmental performance, which is consistent with the impression management argument. In an experiment (Elliott, Jackson, and Peecher, 2014), research found that investors who are exposed to, but do not make an explicit assessment of a firm's CSP, unintentionally overvalue firms with higher CSP. The study argues that CSP causes an increase in investors’ willingness to pay “via their own unintentionally influenced fundamental value estimates,” and if enough market participants believe this, it can even reduce a firm's cost of capital. Although the authors use “affect-as-information” theory from psychology to explain this unintentional influence in valuation, one can also suspect that this is a product of successful window dressing of CSP by a firm that can lure the investors to increase their willingness to invest. Supporting this suspicion, evidence document that firms manipulate visual aids such as photos and graphs in their sustainability reports to play in their favor, to exaggerate their CSR practice or performance (Cho, Michelon, et al., 2012; Hrasky, 2012). In a similar study, upon analyzing the language used in corporate environmental disclosure, there is more optimism, yet less certainty, in the information disclosed by firms who have poor environmental performance (Cho and Roberts, 2010). This extends to sustainability membership, as membership in DJSI appears to be based on self-reported information by the firm, rather than their true CSR performance (Cho, Guidry, et al., 2012). Taking these results together, it can be argued that firms use disclosure and exposure tactics to achieve greater impression management as investors are subconsciously affected by such factors without proper assessments of CSP.

The current SEA research framework of corporate legitimacy is not without strong criticism. Parker (2005) argues that legitimacy theory “suffers from problems that include apparent conceptual overlap with political economy accounting theory and institutional theory, lack of specificity, uncertain ability to anticipate and explain managerial behavior and a suspicion that it still privileges financial stakeholders in its analysis” (Parker, 2005: 846). Thus, the quest for theoretical frameworks in SEA research continues. In a direct response to Parker's (2005) critique, Bebbington and Larrinaga-Gonzalez (2008b) suggest numerous potential theoretical approaches, including contingency theory (Adams and Larrinaga-Gonzalez, 2007), structuration theory (Buhr, 2002), and institutional theory. Adams and Larrinaga-Gonzalez (2007) recognize that criticism of theories in social accounting is potentially harmful if relied upon too heavily, as it will prevent new theories from emerging. They also point out that SEA researchers need to pay closer attention to the interaction between organizations and the participants, as management accounting and control system are contingent upon those factors. It aligns with Buhr's (2002) application of structuration theory, where structural duality between agents and structure dictates the creation and reproduction of social dynamics. Fernando and Lawrence (2014) proposed a framework that integrates stakeholder theory, legitimacy theory, and institutional theory, which makes convergent predictions of organizational behaviors, motivations, and CSR practices. Cho, Laine, et al. (2015) bring the concept of “organized hypocrisy” by Brunsson (1993), and organizational façades (Abrahamson and Baumard, 2008; Nystrom and Strabuck, 1984) to the CSR disclosure literature to explain the gap between firms’ talk, decision and action.

Brammer and Jackson (2012) argue that institutional theory is an appropriate avenue in explaining CSR but have been neglected by researchers so far. Institutional theory is concerned with how an organization is influenced by a broad spectrum of other social institutions. Matten and Moon (2008) divides CSR as “explicit” and “implicit,” stating that CSR is explicit in liberal market economies, while it is more implicit in other institutional settings (i.e., coordinated market economies). Through the view of neo-institutional theory, voluntary CSR practices in Western Europe act as an imperfect substitute for an institutionalized form of stakeholder participation (Jackson and Apostolakou, 2010). Cormier and Magnan (2005) apply institutional theory to explain CSR disclosure. They posit that “the evolution of corporate environmental disclosure quality over time is consistent with (1) what other firms do in that respect, either in the same industry (imitation) and (2) what the firm has done in the past (routine) and regulations, laws and customs (institutions).” In addition to information costs, they found the existence of imitation and routine as determinants of environmental disclosure quality in large German firms. Alternatively, firms can use CSR disclosure to lessen the effect of failure to comply with laws or regulation; to protect their legitimacy in society, they will use institutionalized tools including CSR disclosure. However, for sophisticated information users (i.e., financial analysts), ethical failures dampen the effect of CSR disclosure and corporate legitimacy in their market forecast (Cormier, Gordon, and Magnan, 2016).

Measuring CSR

While there are multiple measures of financial performance, such as accounting performance, economic performance, and stock market performance, they tend to be less controversial due to their objective, monetary, and quantitative nature. On the other hand, social and environmental measurements, such as corporate sustainability performance and CSR disclosure quality, are inevitably ambiguous in comparison as they convey non-monetary and often qualitative and subjective elements. Hence, it is important to review social and environmental performance indicators and ratings because the investors might misallocate resources, and other stakeholders will be misled. The relationship between CSP-CFP can be understated or overstated if the CSR metrics are noisy indicators of true CSR activities (Chatterji and Levine, 2009). Other major concerns known to the CSR research are related to theoretical foundations and methodological domains (Orlitzky and Schmidt, 2003; Ruf, Muralidhar, Brown, and Janney, 2001). Depending on how the model is designed and framed along with the variables included, the relation can bring about opposing scenarios and mixed outcomes. As a result, this inaccuracy and confusion add little value to the information users. Orlitzky and Schmidt (2003) identified three key factors that can explain the cross-study discrepancy in CSP and financial performance relationships in their meta-analysis. Using diverse subsets, they found that stakeholder mismatching, sampling error, and measurement error account for 15 to 100 percent of the cross-study variation.

Database selection based on predetermined criteria is a sampling strategy that can produce stronger and more accurate outcomes in research analyses. The Domini Social Index 400 (DSI 400) is a market capitalization-weighted index developed by Kinder, Lydenberg and Domini (KLD). DSI 400 is composed of common shares of 400 US firms that satisfy multi-faceted social requirements. It first rules out controversial industries such as tobacco, gambling, and weaponry, then screens the companies according to their community relations, corporate governance, diversity, employee relations, environment, human rights, product quality, and controversial business issues. Becchetti and Ciciretti (2009) conducted matching portfolio analysis based on this DSI 400 index. Another database that serves the same sample selection purpose as DSI 400 is DJSI. There is a difference between them in how the companies are selected. Unlike the DSI 400 that goes through a process of elimination, DJSI firms are determined by whether they meet certain sets of criteria, hence it is an addition process. The DJSI has five composition criteria: (i) the capability of a firm to integrate economic, environmental, and social strategies into their business and maintaining its competitiveness; (ii) the financial strength to lead its industry in satisfying shareholders’ needs, long term economic growth, open communication and transparent financial accounting; (iii) customer relationship management and innovation that incorporates CSR; (iv) corporate governance and stakeholder engagement; and (v) labor relations. The DJSI is comprised of about 200–300 companies across the globe, an appropriate sample to carry out matched portfolio analysis (Lee and Faff, 2009). The DJSI looks to be a convenient, pre-selected sample index representing organizations with the best CSR practices, but its heavy reliance on economic and financial performance as part of the screening makes it less ideal than it appears. Furthermore, as pointed out by Cho, Guidry, et al. (2012), the DJSI is primarily based on self-reported information, which is subject to a bias. It is possible that the companies that are already financially superior to the firms in the control sample will be included in the portfolio, causing endogeneity and biased estimation of correlations between CSP and CFP. Thus, when using sustainability indices, caution and careful attention should be paid to assess the requirements and screening process as well as the relative weight of each criterion whenever possible.

One of the popular environmental performance metrics is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)'s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI). It is composed of approximately 650 chemicals released to air, water, and land in a given year in pounds (lbs) at plant level, and can be aggregated to determine firm level performance. The companies are required to self-report once the toxic release meets a certain level, and it is done at the factory level. As expected, most of the firms that report to the EPA are those that pollute the most, including manufacturing, metal and coal mining, electric utilities, commercial hazardous waste treatment, and other industrial sectors.4 It is particularly useful to the scholars who exclusively want to examine environmental dimension within CSR. The data is available to the public from EPA website. Note that environmental data is published by the EPA with a 2-year lag (Clarkson, Li, et al., 2011), and it does not consider any forward-looking elements of environmental performance or strategy. The timing difference between the publication of TRI and other financial performance measurements used in CSP-CFP research could be problematic, especially when coupled with capital market data. In order to have capital market implications, the information must have an impact on the “expectations,” and 2-year lag could be considered too outdated to have any earth-shattering influence on the market expectations. When using TRI as a measure of CSP, it is scaled to the company's size, such as cost of goods sold (Clarkson, Li, et al., 2011), sales, or production (Wagner et al., 2002), since it is un-weighted by categories and un-scaled by the company's size. One thing to keep in mind is that an environmental policy could be contradictory to its purpose in the sense that improvement in one area of operation could result in a fall back in another area. For instance, the removal of a pollutant from a factory may require the use of a chemical from which a very harmful effluent is produced (Owen, 1992: 271). Thus, depending on what is being measured as environmental performance, the results could differ severely. Now, consider TRI data that reports the level of toxic waste and pollutant produced by a plant in pounds, and there is a threshold of pollution before reporting is required to TRI. The severity of a specific type of pollution may be more toxic than another, but the quantifiable weight could be less in comparison, therefore not required to disclose. Does this accurately capture the true environmental performance of a firm?

KLD is perhaps the most popular database today for measuring the aggregate CSP. While the studies that focus on the environmental aspect of CSP often use TRI as a proxy for CSP, when a broader definition of CSR is employed, KLD ratings are the dominant choice among researchers. KLD rates social and environmental dimensions of over 3,000 publicly traded U.S. companies5 and measures both past outcomes and recent management actions that could have an impact on the future performance. The qualitative screening process for KLD is divided into several categories, and assessed based on the strengths and concerns for each category. The categories are community, corporate governance, diversity, employee relations, environment, human rights, and products. KLD also has exclusionary screens with only concern ratings, for categories including alcohol, gambling, firearms, military, nuclear power, and tobacco. This rating process is identical to the process of forming DSI400 index.

Among the studies using KLD data, there is an inconsistency in how indices of these data are formed. One simple method to calculate composite KLD ratings is to add up the strengths items and subtract the concerns items to come up with a score (Mahoney and LaGore, 2008; Mahoney and Roberts, 2007). Callen and Thomas (2009) assigned a value on a 5-point scale for each of the qualitative screening category, where −2 indicates that there are two or more concerns, −1 indicates a single concern, +2 is for two or more strengths, and +1 for a single strength. Some prefer to use a weighted calculation developed by Waddock and Graves (1997), where they used expert panel evaluations on the relative importance of each CSR attribute (Nelling and Webb, 2009). The weighting of the qualitative screening categories can be debated, and is subject to diverse opinions. Also, there is no single best way to compose KLD ratings and scores agreed upon the researchers. Therefore, despite the popularity of KLD, the results across different studies can be somewhat difficult to infer because the composition of customized KLD ratings for each study could vary. Chatterji and Levine (2009) tested whether the environmental category of KLD ratings is a good reflection of the past environmental performance, as well as its ability to predict future environmental performance by examining KLD environmental rating against TRI data. They found that KLD “concern” ratings explain the past environmental performance, but “strengths” do not accurately predict pollution levels or compliance violations of the future. Delmas and Blass (2010) suggested that investors face trade-offs when choosing one environmental performance indicator over another, and that they must be cautious in selecting screening methodology, indicators, and relative weights assigned to the measures. Although they only examine environmental dimension of CSP, the extension of this evaluation into multiple dimensions of CSP will be interesting.

Although not as commonly used, there are alternative measurements for CSP. Aktas and de Bodt (2011) used the Intangible Value Assessment (IVA), which aggregates 120 performance factors including “innovation capacity, product liability, governance, human capital, emerging markets, and environmental opportunities and risk.” The rating for IVA is similar to that of a bond rating. It ranges from AAA where a company has “minimal, well-identified environmental/social risks and liabilities, and with a strong ability to meet any losses which might materialize,” to CCC “where there are significant doubts about management's ability to handle its environmental/social risks and liabilities, and where these are likely to create a serious loss, well below-average ability to capitalize on environmentally/socially-driven profit opportunities” (Aktas and de Bodt, 2011). Singh, Murty, and Gupta (2012) review a variety of sustainability indices applied in policy practice, that SEA researchers may be interested in utilizing. They give a brief overview of indices in terms of its formulation, scaling, weighting, and aggregation methodology across 12 categories including development, market and economy based, eco-system, composite sustainability performance, and investment, ratings, and asset management.

In terms of control variables, most of research control for industry membership of firms, firm size, and risks, while other control variables that are likely to influence CSP and financial performance go unnoticed. Although it is virtually impossible to control for everything, misspecification issues caused by omitted variables can cause biases in the outcomes. For instance, both CSR and R&D are related to innovation and strategy, thus possibly highly correlated. It is argued that not controlling for a firm's R&D will result in a positive, upward bias in the correlation between CSP and financial performance, and found that CSR has no impact on financial performance after controlling for R&D investments (McWilliams and Siegel, 2000). Konar and Cohen (2001) include the advertising expenditure as an important control variable. If one is convinced by the impression management argument, the extent of a company's environmental and social appeal to the public could have an impact on CSP.

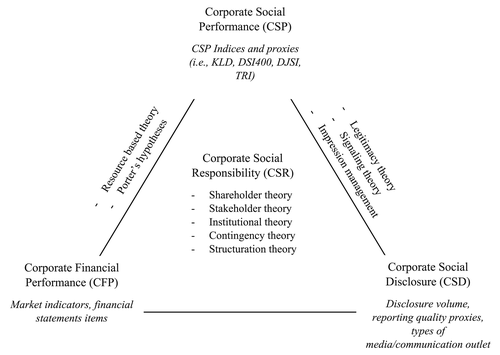

In the CSR disclosure literature, the level, frequency, and type of information often dictate the quality of disclosure. However, the level of information disclosed proved to be a questionable measure of quality, as there is documented evidence supporting that quantity does not equal quality (Cho, Freedman, et al., 2012; Frost and Seamer, 2002; Hasseldine and Salama, 2005). Hasseldine and Salama (2005) weigh the likely significance of the content within CSR reports following the quality score scheme developed by Toms (2002), which is based on the imitability of information. It is common to assess the type of information in terms of “hard” vs. “soft” information, where “hard” type of information carries more certainty, is objective, and is often quantified, and “soft” types of information is vague and subjective (Cho and Roberts, 2010; Cho and Patten, 2007; Clarkson, Overell, et al., 2011). Although information quality is difficult to assess, distinguishing “hard” vs. “soft” types of information appears to be the agreed upon method of analysis among SEA researchers. Since many companies follow the GRI guidelines for CSR reporting, how many information categories were disclosed according to GRI framework is now also used as a quality measurement. Therefore, frequency, level, and type of information can be used in conjunction to complement each other (Michelon et al., 2015) (Figure 2).

Theories and measurements applied in assessing CSP, CSD, and CFP relations

Conclusion

The notion of CSR rapidly became popular and has been explored rigorously by the academic community. This article examined current trends in SEA research from existing bodies of literature in accounting and other relevant disciplines of CSR research. SEA started to gain publicity in some of the most cited accounting journals in the recent few years, and there are many academic journals exclusively dedicated to corporate sustainability that have emerged recently due to increasing demand for SEA research. However, there is a lack of communication between the existing scholars of SEA, and those who have recently entered the SEA conversation and project. Without discounting any effort, expanding one's scope of SEA research will enrich the scholarly conversation and cultivate further advancement of the topic. This article does not claim to have covered the SEA literature in its entirety, but simply aimed at presenting a broader scope in the journals reviewed.

After 40 years of active research, SEA has more opportunities for positive growth. Identifying new sustainability performance measurements and databases outside of the traditional realm, investigating emerging economies, and further examinations of less explored subtopic areas, such as taxation and merger and acquisition (M&A), small and medium enterprises can be some of the ways to move forward. In addition, there are suggestions made to involve various stakeholder groups in the research initiatives (Owen, 2008), and engage them to address some of the less comfortable but perhaps unavoidable areas of political conflicts (Tinker and Gray, 2003). The CSR literature will continue to flourish and remain lucrative for current and future researchers, but not without persistent effort for improvements and development.

Footnotes

Appendix

List of academic journals affiliated with the American Accounting Association (AAA)

| Issues in Accounting Education |

| Accounting Horizons |

| The Accounting Review |

| Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory |

| Behavioral Research in Accounting |

| Current Issues in Auditing |

| Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting |

| Journal of Forensic Accounting Research |

| Journal of Governmental & Nonprofit Accounting |

| Accounting Historians Journal |

| Journal of International Accounting Research |

| The ATA Journal of Legal Tax Research |

| Journal of Management Accounting Research |

| Accounting and the Public Interest |

| Journal of Financial Reporting |

| Journal of Information Systems |

| The Journal of the American Taxation Association |