The Impact of Better-than-Average Bias and Relative Performance Pay on Performance Outcome Satisfaction†

Abstract

enDrawing on equity and expectancy theories, we hypothesize that the perception of accountants about their ability to contribute relative to a peer (operationalized as the better-than-average [BTA] bias) negatively influences their satisfaction with the outcomes of the performance evaluation process (operationalized as performance outcome satisfaction [POS]). We hypothesize further that this negative influence is mitigated by the amount of relative performance pay. We test these hypotheses using data collected from a survey of and an experiment involving 164 entry-level accountants. We found that in general our participants rated themselves better than the average audit professional and their immediate work associate; that is, they displayed a BTA bias. Moreover, we found that both the BTA bias and performance pay individually influenced POS; we also found a moderately significant interaction effect. In their entirety, the results indicate that the greater an entry-level accountant believes that she or he is better than average the more likely her or his performance outcome satisfaction will fall.

L'incidence du biais de supériorité par rapport à la moyenne et de la rémunération liée au rendement relatif sur la satisfaction à l'égard des résultats du processus d'évaluation du rendement

frRésumé

En s'inspirant des théories de l'équité et des attentes, les auteurs font l'hypothèse que la perception des comptables quant à leur capacité d'apport par rapport à celle de leurs pairs (notion qu'ils définissent comme étant le biais de supériorité par rapport à la moyenne [better-than-average—BTA]) a une incidence négative sur leur satisfaction à l'égard des résultats du processus d'évaluation de leur rendement [performance outcome satisfaction—POS]. Les auteurs formulent en outre l'hypothèse selon laquelle cette incidence négative est atténuée par le montant de la rémunération liée au rendement relatif. Ils vérifient ces hypothèses à l'aide de données tirées d'un sondage et d'une expérience menés auprès de 164 comptables débutants. En général, constatent-ils, les participants à l'étude s'attribuent un classement supérieur à celui de l'auditeur moyen et de leur collègue de travail immédiat, c'est-à-dire qu'ils affichent un biais de supériorité par rapport à la moyenne. Ils observent au surplus que le biais de supériorité par rapport à la moyenne de même que la rémunération au rendement ont individuellement une incidence sur la satisfaction à l'égard des résultats du processus d'évaluation du rendement ; ils observent également une interaction d'ampleur modérée. Dans leur ensemble, les conclusions de l'étude indiquent que plus la supériorité du classement que s'attribue le comptable débutant par rapport à la moyenne est grande, plus sa satisfaction à l'égard des résultats du processus d'évaluation de son rendement est susceptible de chuter.

Prior research in psychology has documented the existence and causes of the better-than-average (BTA) bias in individuals (Alicke, 1985; Alicke, Klotz, Breitenbecher, Yurak, and Vredenburg, 1995). BTA bias is an individual's perceived ability to contribute to an organization relative to that of a peer. There is also extensive literature on the topic of job satisfaction (Lawler, 1971, 1990; Crosby, 1976; Society for Human Resource Management [SHRM], 2012). Job satisfaction is a multifaceted concept encompassing an individual's satisfaction with various aspects of the job such as the job or the task itself, compensation, the job environment, safety, variety of work, supervision, training, knowledge and capabilities of the individual, and management's evaluation and recognition of the performance outcomes. Our study is an attempt to connect these two streams of research (i.e., BTA bias and job satisfaction), as posited in the following research questions:

- Do entry-level accountants display a BTA bias?

- Does BTA bias affect their perceived performance outcome satisfaction (POS)?

- Does relative performance pay affect their perceived outcome satisfaction?

- Does relative performance pay (RPP) moderate the impact of BTA bias on POS?

Performance outcome satisfaction is a construct comprising the following two components of job satisfaction: the satisfaction of an employee with his or her relative performance pay and his or her relative performance evaluation (SHRM, 2008, 2012; Vidal and Nossol, 2011).

The research questions we explore in our study were motivated by a number of factors. Prior research on BTA bias (Alicke, 1985) has established its existence among employees in general and shows that the magnitude of the bias diminishes when the comparison other changes from someone in the general population to someone more specific. This finding leads us to ask if BTA bias will exist in populations where the comparison other is precisely identified and the individuals have shared a well-defined common educational experience and training as in a variety of professions like accounting. The existence of BTA bias in accountants and the impact of BTA bias on the POS of accountants are both open questions that need to be verified by empirical research and the answers to which cannot be directly inferred from the results of prior research. We are not aware of any other study that has examined the relationship between BTA bias and POS.

Like any other organization, an accounting organization has the need and desire to understand the factors that can affect the performance outcome satisfaction of its employees. Accounting organizations are also unique in that they sell professional services—knowledge and expertise—with a cadre of employees who are a high-achieving, highly educated group with a clear sense of self identity (Aranya, Lachman, and Amernic, 1982; Aranya, Pollock, and Amernic, 1981; Elias, 2006).

Accounting firms represent knowledge-based organizations (Sheehan, Vaidyanathan, and Kalagnanam, 2005) that rely exclusively upon the capabilities, knowledge and expertise of their employees. Generally speaking, like most other professionals, accountants are likely to have a heightened sense of their potential to contribute and a greater sense of self-worth and therefore have higher expectations of the performance pay that they should receive. Consequently, the population of professional accountants is one in which we expect its members to have strong perceptions that they are better than average when comparing themselves to individuals from the general population. But will accountants exhibit a BTA bias when the comparison other is a specific fellow accountant who has also undergone similar educational and professional training?

Professional accountants are expected to exercise professional judgment (Chartered Professional Accountant Competency Map, 2013). Education and training as auditors and controllers will have highlighted the imperfect nature of the judgment process endemic in performance evaluation and in the application of accounting principles in decision making (Norris and Niebuhr, 1984). The consequence of this training and exposure to exercising and being subjected to professional judgment is that the existence and the strength of BTA bias in accountants is a priori an open question and the motivation for the first research question. We therefore believe that the practice of accounting and the nature of the accounting profession possess characteristics that contribute to viable null hypotheses.

Recruitment and retention of qualified accountants is a growing challenge facing accounting firms and other organizations wanting to hire accountants (AICPA, 2003; Chatzogiou, Vraimaki, Komsiou, Polychrou, and Diamantidis, 2011; Lornic, 2006; Moyes, Shao, and Newsome, 2008; Parker and Kohlmeyer, 2005; Robinson, 2006). In this type of environment, organizations that are successful in enabling their employees to achieve job satisfaction are more likely to overcome the challenges of recruitment and retention.

An improved understanding of the factors that can affect the job satisfaction of its employees can also help an organization avoid the negative consequences that can result when employees are dissatisfied (Larkin, Pierce, and Gino, 2012). Examples of negative consequences include absenteeism, poor quality work, and an increase in employee turnover. The cost to the accounting organization to address these types of challenges and restore customer confidence can be significant.

In this context, the impact of BTA bias on performance outcome satisfaction, a priori, is also an open question worthy of empirical study and is embodied by our second research question. Performance evaluation in knowledge-based organizations, like accounting firms, is largely subjective because the capabilities of the employees and their application of those capabilities in performing their job are less easily measurable (Klassen, 2013). This implies that performance evaluations and performance pay may be less predictable resulting in a higher frequency of divergences between expectations and actual outcomes.

By contrast, in industrial organizations the knowledge and expertise of frontline employees and their application of their capabilities in performing their jobs is more easily measurable because the association between an individual's contribution and the output is better defined (Klassen, 2013; Sheehan et al., 2005). This implies that performance evaluations and performance pay may be more predictable in this organizational environment and consequently there is limited scope for BTA bias to impact POS and overall job satisfaction. Prior research on BTA bias (Alicke et al., 1995; Brown, 2012; Hales and Kachelmeier, 2005; Kanten and Teigen, 2008; Seta, Seta, and McElroy, 2006; Yeoh and Wood, 2011) is silent on these aspects.

In addition to the foregoing, there has been a paucity of recent research in the area of performance pay (Ross and Bomeli, 1971; Strawser, Ivancevich, and Lyons, 1969) and the economics of job satisfaction in the accounting profession (Clark and Oswald 1996; Larkin, Pierce, and Gino, 2012). Prior research on job satisfaction among accountants (Bamber and Iyer, 2009; Ferris, 1977; Lombardi and Flamholtz, 1985; Moyes, Shao, and Newsome, 2008; Norris and Niebuhr, 1984; Reed, Kratchman, and Strawser, 1994; Spathis, 1999) has not incorporated the effect of performance pay or BTA bias on job satisfaction. One notable exception is the study by Parker and Kohlmeyer (2005), which examined the perceived fairness of decisions involving pay and promotions in major Canadian accounting firms; however, this paper also did not consider BTA bias. There is some research outside of accounting on the link between performance pay and job satisfaction (Green and Heywood, 2008), but again this research did not consider the impact of BTA bias.

The possibility that the performance evaluation process (Fletcher, 2001; Gabris and Ihrke, 2001; Sudin, 2011) for accounting firms may produce undesirable results due to the presence of BTA bias among employees is worthy of investigation. The potential findings of our study should be of interest to management because, when forewarned, management may be able to take corrective actions that are sensitive to the existence of BTA bias among employees. For example, if confirmed, the negative influence of BTA bias on POS is evidence that it should be on management's radar. Similarly, a finding of positive influence of relative performance pay on POS would be evidence that pay matters to accountants: the higher the relative performance pay received, the higher the reported POS. Moreover, a positive interaction effect, if it exists, would be evidence that relative performance pay can be a strategic tool that management can use to influence positively at least two components of job satisfaction, or at least counteract the potential negative influence of BTA bias on job satisfaction.

To summarize, our study seeks to contribute to the literature on the use of performance pay by focusing on the antecedents of performance outcome satisfaction (POS), an important component of job satisfaction. Our study is unique in that our measure of an individual's perceived contribution focuses on the capabilities side through the use of BTA bias rather than the output side, such as an individual's productivity.

We tested our hypotheses using data collected through a survey and an experiment involving 164 entry-level accountants. Our results provide strong evidence and support for the first three questions and moderate support for the fourth. The results indicate that (1) entry-level accountants exhibit a BTA bias, (2) BTA bias negatively influences POS, and (3) relative performance pay moderates the negative impact of BTA bias on POS.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section we develop our hypotheses, following which we describe our research methodology and then present our results. Finally, we conclude the paper with a summary of our findings and their potential implications. We also discuss some of the study's limitations and provide suggestions for future research.

Theory and Hypotheses Development

Job satisfaction is a multidimensional construct that pertains to satisfaction along several dimensions such as (1) performance evaluation, (2) performance pay, (3) promotion, (4) supervisors, (5) coworkers, (6) work environment, and (7) the job itself (Smith, Kendall, and Hulin, 1969). Lawler's (1971, 1990) research suggests that job dissatisfaction most likely occurs when an individual receives less pay than what he or she expects to receive. Moreover, respondents to a job satisfaction survey conducted by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) ranked Compensation/Pay among the top three factors contributing to job satisfaction in seven out of ten years between 2002 and 2012 and among the top five in all ten years. For example, in 2008 (2012) 92 percent (98 percent) of the respondents rated compensation/pay as important or very important. Additionally, 37 percent (39 percent) rated opportunities for variable pay (including bonuses, commissions, and other forms) as very important. Similarly, 82 percent (90 percent) of the respondents to the survey in 2008 (2012) rated management's recognition of employee performance as important or very important to achieving job satisfaction (SHRM, 2008, 2012). These results reinforce the importance of satisfaction with performance pay and satisfaction with performance evaluation as critical dimensions of job satisfaction, and our research focuses on these two dimensions, which we combine into a single construct called performance outcome satisfaction (POS).

Pay for performance is considered a critical component of an organization's management control system for managing employees' job satisfaction (Kaplan and Norton, 2001; Merchant and Van der Stede, 2003; Otley, 2003) and is widely used in organizations. For example, Long (2002) reported that 94 percent of Canadian organizations use some type of performance pay, with individual performance pay being the most common (88 percent). Organizations use pay for performance to increase goal congruence, employee motivation, and ultimately job satisfaction (Lawler, 1971; Long, 2002, 2010; Otley, 2003; SHRM, 2012).

Recent surveys by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA) of its members indicate that compensation, including performance pay, ranks among the top five factors that respondents consider important (CICA, 2006, 2007). In fact, it can matter to such an extent that, according to Parker and Kohlmeyer (2005) and the SHRM survey (2012), negative perceptions regarding pay can lead to lower job satisfaction, decreased organizational commitment, and increased turnover in organizations. However, recent research also suggests that the role of pay for performance as it pertains to job satisfaction has not been resolved (Green and Heywood, 2008).

Crosby's (1976) research suggests that pay dissatisfaction, which results in low POS, occurs under the following conditions: (1) when individuals are aware that their peer (the target used in their comparison) received more than they did; (2) when there is an inconsistency between the outcome individuals expect and the amount they actually receive; (3) future expectations for achieving better outcomes are unlikely; and (4) they absolve themselves of any personal responsibility for the lack of better outcomes. Of the four conditions, the first two in particular have received considerable attention in prior research (Chatzogiou, Vraimaki, Komsiou, Polychrou, and Diamantidis, 2011; Moyes, Shao, and Newsome, 2008). The findings suggest that most employees will not object to performance pay if it is consistent with what they perceive as equitable, is in line with their expectations, and is clearly in addition to their base pay.

High relative performance pay can potentially narrow the gap between an individual's expected and actual performance outcome (Long, 2010; SHRM, 2012). This is because the individual perceives a higher relative performance pay as an acceptable outcome given his or her perceptions about his or her contribution relative to his or her peer. This is a key tenet of equity theory (Adams, 1965). Consequently, a high relative performance pay can reduce the degree of inconsistency between expected and actual performance outcome which, in turn, will result in a greater likelihood of the individual reporting increased satisfaction with his or her performance outcome.

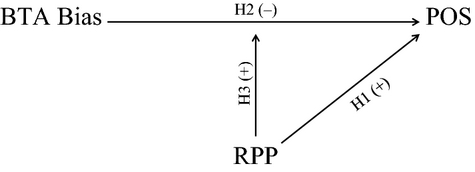

The preceding discussion leads to our first research hypothesis (see Figure 1):

Hypothesis 1. Performance outcome satisfaction (POS) is positively related to relative performance pay.

Vroom (1964), Adams (1965), and Lawler (1973) introduce an employee's perception of his or her contribution and the reward they receive (or do not receive) as determinants of job satisfaction. Individuals incorporate these elements by developing an implicit contribution–reward (C–R) ratio (Schein, 1965) based on the perceptions of their contribution (i.e., effort) and the reward (e.g., performance pay) they expect for the contribution. When the reward an individual receives does not meet his or her expectation, the greater the possibility of dissatisfaction because the perceived (self-assessed) C–R ratio will deviate from the actual C–R ratio. This leads to the prediction of an inverse relationship between the deviation in the C–R ratios and the POS.

However, this theory is silent on the factors that influence the individual's perceived C–R ratio. Based on expectancy theory (Ferris, 1977), we conjecture that an individual's perceived ability to contribute relative to a peer—the BTA bias—is a key determinant of his or her perceived C–R ratio. Individuals with a BTA bias will have a strong sense of self-efficacy and will believe that they can (1) contribute more to the job than the peer and (2) meet the expectations of the job. This will result in a high expectancy. Individuals with a high BTA bias will also expect to receive a relatively more favorable performance evaluation and reward, which will result in high instrumentality. Together this high expectancy and high instrumentality will contribute to a high perceived C–R ratio.

Hypothesis 2. Performance outcome satisfaction (POS) is negatively related to BTA bias.

Hypothesis 3. Relative performance pay positively interacts with BTA bias in influencing POS.

Research Methodology

In this section we present the research methodology, including the study's design, its participants, and the variables used. Two groups of 80 and 84 (total 164) entry-level accountants in public practice, who were also students in a graduate accounting program, participated in the study. We adopted a hybrid design comprised of a survey followed by an experiment involving two case studies and concluding with a post-experimental questionnaire.1

Survey

We used a survey to collect BTA scores and establish the existence of BTA bias. Participants assessed themselves, relative to two target peer groups, on the 24 traits identified by Libby and Thorne (2004) as essential for auditors to possess (see Table 1). The two peer groups were as follows: (1) an individual representing an immediate work associate (i.e., a fellow classmate), and (2) a general comparison target—the average professional auditor—representing a broad comparison group. The use of two peer groups was to confirm findings in prior research that BTA bias diminishes as the peer group becomes more focused (Alicke, 1985; Suls, Lemos, and Lockett, 2002).

| Trait: | t-value |

|---|---|

| Alert | 17.040*** |

| Altruistic | 4644*** |

| Benevolent | 0.576 |

| Careful | 30.006*** |

| Cheerful | 2.975*** |

| Concerned with public interest | 32.345*** |

| Cooperative | 13.561*** |

| Courageous | 10.481*** |

| Diligent | 27.885*** |

| Enlightened | 5.128*** |

| Even-handed | 10.804*** |

| Farsighted | 11.737*** |

| Healthy skepticism | 37.503*** |

| Independent | 28.483*** |

| Integrity | 52.195*** |

| Objective | 37.950*** |

| Polite | 5.787*** |

| Principled | 24.087*** |

| Resourceful | 16.280*** |

| Sensitive | −0.574 |

| Tactful | 8.580*** |

| Thoughtful | 5.270*** |

| Truthful | 25.059*** |

| Warm | −2.579** |

| N = 164 | |

| df = 163 |

Notes:

- This table provides a list of the traits used to measure the existence of BTA bias. The t-values pertain to the ratings provided by participants with respect to the importance of each trait for their job as entry-level accountants.

- * significant at p ≤ 0.10, ** significant at p ≤ 0.05, *** significant at p ≤ 0.01.

We use the 24 traits because they are considered important for auditors to possess; that is, they are relevant to the entry-level accountant's job, which is primarily audit-related.2 Consistent with our discussion of expectancy theory in the previous section, we believe that possessing these traits rather than other general traits will potentially increase an individual's self-efficacy with respect to the audit function. We used a 9-point Likert scale anchored as follows: 0 = much less than the target group or individual, 4 = about the same as the target group or individual, and 8 = much more than the target group or individual.

As a form of control the order of the self-assessment peer groups was varied between the surveys completed by the participants. The rationale for this manipulation in the ordering sequence was to ensure construct validity of BTA scores and the POS measures we would be obtaining. By providing a well-defined and familiar peer, such as a fellow classmate seated next to the subject participant, we believe that BTA scores and the POS measures would be more strongly anchored than if they were based on comparisons with a general target group. At this point the participants were unaware that the primary BTA scores used in our research study would be those that required them to compare themselves specifically to their adjacently seated classmates.

Furthermore we believe that this plan was more representative of the process that would occur in accounting firms when performance evaluation outcomes were awarded. It was likely that an employee would be more inclined to choose the peer to be a familiar work associate similar to themselves rather than someone they did not know. It should be noted that the participants in our study knew each other very well; this put them in a better position to assess themselves relative to their comparison other. In contrast, participants in Alicke's (1985) study were only given three minutes to know their comparison other. Consequently our experimental condition allowed us to have a greater degree of confidence in the BTA scores we elicited from the participants. Moreover the fact that BTA bias exists despite each participant being strongly familiar with the peer is very telling of one's perceived self-efficacy relative to a peer.

Experiment

The purpose of the experiment was to provide us with performance outcome satisfaction (POS) data. Each participant read two case studies that placed them in a realistic scenario occurring in an accounting firm. Each scenario described the participant's performance as well as the performance of his or her immediate work associate and the results of the subsequent performance evaluation including the amount of performance pay awarded to the participant (the respondent) and his or her work associate. The two cases differed only with respect to information about the amount of the performance pay awarded to the participant (the respondent) and his or her immediate work associate. In Case 1 (2), we stated that as an outcome of the performance evaluation the participant received performance pay of $1,500 ($500) whereas the participant's immediate work associate (i.e., the individual they were asked to compare themselves to) received $500 ($1,500).3 Thus in Case 1 (2), the participant would be able to infer that he or she received $1,000 more (less) than his or her immediate work associate.

After reading each case study, the participant responded to 31 questions using a 9-point scale. The questions were distributed as follows: 16 pay- and work-related questions, 2 manipulation check questions, and 13 general information and background type questions. The purpose of the questionnaire was to elicit the participants' ratings of their satisfaction with their performance pay and the satisfaction with their performance evaluation which, when combined, provided us with a measure of their performance outcome satisfaction (POS). To reduce the possibility of creating a demand effect, we randomly distributed the questions addressing the variables of interest throughout the questionnaire section of the case study.

Post-Experimental Questionnaire

Finally, participants completed a questionnaire through which we obtained their assessment of the importance of the 24 traits (Libby and Thorne, 2004) that we used to measure BTA bias. Using a 10-point scale (anchored at both ends by 0 = Not at All Important and 9 = Very Important), participants rated how important it was for auditors to possess each of the 24 traits. In addition participants answered a few general questions addressing demographic-type information.

Variables Used in the Study

The BTA bias is defined as the difference between their actual total BTA score and the total BTA scale mean. In our scale, the maximum possible score for each trait is 8, so the maximum total score for the 24 traits is 192 (24 × 8). The scale mean for each trait is 4, so the total BTA scale mean is 96 (24 × 4). However, we use the total BTA scores as our measure of BTA bias to test the study's hypotheses.

Relative amount of performance pay (RPP), the other independent variable, was constructed as a dichotomous variable and was set at an amount of either $500 or $1,500 consistent with the information provided in the cases (coded as 0 and 1 for the purpose of the analysis).

The dependant variable, POS, is constructed as the sum of an individual's satisfaction with his or her relative performance pay and the individual's satisfaction with his or her relative performance evaluation. The logic behind this construction of POS is that in situations where pay for performance exists the overall outcome of the performance evaluation process (i.e., performance outcome) consists of two separate, but related, components: (1) the relative performance evaluation rating (i.e., how one's performance is rated relative to others) and (2) the consequence of the evaluation, which is a reward or a punishment (higher or lower relative performance pay).

In addition to the usual difficulties in obtaining data from organizations, there is the additional difficulty that, when relative performance is communicated in firms, it typically has explicit or implicit monetary consequences. For instance, a worker being informed that he has performed better than his colleagues may reasonably conclude that he has a chance of receiving a promotion to a better paid position, which could translate into higher effort. This makes it difficult to disentangle the direct effect of relative performance feedback from the effect of the monetary reward to which such feedback is often linked.

For this reason we provided participants both the information regarding the outcome of their performance evaluation and the performance pay ($500 or $1,500) at the same time (i.e., together).4 For the reasons cited above we do not deconstruct our POS construct and analyze the impact of our independent variables upon each of its individual POS components separately (i.e., performance pay satisfaction and performance evaluation satisfaction).

Results

First we present general descriptive data regarding the participants, followed by the results of our preliminary tests to examine (1) how our participants rated the 24 traits considered as important for auditors to possess and (2) the existence of BTA bias. Next we present the results for each of the three hypotheses in the order in which they were posed. We use the data collected from all 164 participants in conducting our preliminary tests and from 162 participants in testing our hypotheses (two participants failed the manipulation check).

Prior to combining the data collected from the 80 and 84 participants (adding up to 164), we did a number of tests to ensure that the data between the two groups were compatible. We tested for differences in BTA scores by gender, year of study (first- versus second-year student), and alphabetical versus reverse alphabetical order of listing the traits. We found no statistically significant differences between the two groups with respect to gender, year of study, order of pay manipulation in the two cases (i.e., whether the amount of performance pay in the first or second case was less or more than their immediate work associate), and ordering of traits when they compared themselves to their immediate work associate.5

The average age of the 164 participants was 25.29 years; 97 (59 percent) were female, and 67 (41 percent) were male. All but two were employed as entry-level accountants, with an average length of work experience of 13.1 months as accountants. Of the total participants, 156 (95.1 percent) indicated that they were employed in public practice. Moreover, 162 participants (98.8 percent) reported that they plan to pursue a professional accounting designation. One hundred twenty-six participants (77.8 percent) reported that performance pay was used in their accounting firms at the entry accountant level, and 145 (88.4 percent) reported that performance pay was used at some level in the accounting firm where they were employed. One hundred twenty-eight participants (78 percent) responded to the question “generally speaking were you aware of the amount of performance pay received by others working at the same level as you in your firm.” Of these 128 respondents, 91 (71.1 percent) indicated that they were aware of the amount of performance pay received by others in their accounting firm.6 The descriptive statistics highlight both the predominant use of performance pay and a fairly high level of awareness among participants of the amount of performance pay received by their work associates. We believe that the combination of both the high level of performance pay use and general awareness of the amount of performance pay received by others enhances the validity of our study.

Preliminary Tests

We conducted two preliminary tests to examine how our participants rated the 24 traits considered as important for auditors to possess and the existence of a BTA bias among our participants (entry-level accountants).

Importance of the 24 Traits

The 164 entry-level accountants rated each of the 24 traits on a 10 point scale (0 = Not at All Important, 9 = Very Important). The results, as shown in Table 1, indicate that entry-level accountants rated 21 of the 24 (91.7 percent) traits as important (i.e., they assigned a score that was statistically significantly higher than the mid-point score of the scale (as per Alicke et al., 1995); the difference between mean scores of the 164 participants and the midpoint of the scale was positive and statistically significant for 21 of the 24 traits. The difference for the trait “benevolent” was positive, but not statistically significant (t = 0.576, p = 0.566). The trait “sensitive” had a negative difference, but it was not statistically significant (t = −0.574, p = 0.567). Finally the difference for the trait “warm,” although statistically significantly different from zero, was negative, thereby suggesting that participants did not rate it as important (t = −2.579, p = 0.011). Collectively since 21 out of 24 traits were rated as important (i.e., statistically significant) we interpret this as providing overall support for the findings of Libby and Thorne (2004) and ultimately providing support for their use in our study.

We also conducted reliability tests to ensure that we could add the individual BTA scores for the original group of 24 traits as well as for the subset of 21 traits. Our reliability tests resulted in Cronbach's Alpha scores of 0.896 and 0.914 and 0.883 and 0.905 respectively, for comparisons with the average professional auditor and with his or her immediate work associate. In their totality these results support the observation that the 24 (21) trait ratings, for each respective comparison group, consistently reflect the construct (i.e., BTA bias) that it is measuring. Essentially we interpret the results to indicate that the 24 (21) traits included in the instrument provide a reliable measure that can be used to test for presence of BTA bias. Nonetheless, as mentioned above, we aggregate the BTA scores for the subset of 21 traits that were considered important by the participants and used these scores in all the subsequent tests.

Finally a t-test was performed on the entire set of the 21 traits that were rated as important by the sample subjects to examine their overall (combined) importance. The results show that collectively the 21 traits were rated as statistically significant or important (t = 8.536, p = 0.000), which again corroborates the findings of Libby and Thorne (2004) and also provides additional support for using the 21 traits in our study to investigate the presence of a BTA bias for entry-level accountants.

Existence of BTA Bias

Our next preliminary test investigates the existence of BTA bias among entry-level accountants and whether the degree of BTA bias diminishes as the group becomes more focused. The method used in our study to address this question, similar in principle to the one used by Alicke et al. (1995), involved computing (for each of the 164 participants) BTA bias when participants compared themselves to the average professional auditor and when they compared themselves to their immediate work associate. Within each comparison group BTA bias was measured as the difference between the total BTA score for 21 traits and the total scale mean adding up to 84 (21 × 4).

The results presented in Table 2 provide evidence of a BTA bias regardless of the comparison group (p = 0.000 for both comparison groups). We also find a statistically significant difference between the entry-level accountant's comparisons to the average professional auditor and to his or her immediate work associate (t = 20.36, p = 0.000). This finding suggests that BTA bias diminishes as the peer group becomes more focused (see Table 2). This finding was originally reported by Alicke (1985) and Alicke et al. (1995) and our result corroborates that finding for the accounting profession.

| Total BTA score in comparison to: | Mean score | Difference from the mean score of 84 | t-value | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Professional Auditor | 106.043 | 22.043 | 17.530 | 0.000 |

| Immediate Work Associate | 88.884 | 4.884 | 4.993 | 0.000 |

| N = 164 | ||||

| df = 163 |

Notes:

- *Reported p-values are for 2-tailed tests.

Hypothesis Tests

POS = Performance outcome satisfaction

PerfPaydummy = 0 (relatively lower pay) or 1 (relatively higher pay)

BTAbias = BTA bias

WkExp = Length of work experience in months

GENdummy = A gender dummy, 0 = male 1 = female

e = error term

The regression results, shown in Table 3, indicate that the model is statistically significant (F = 293.883, p = 0.000) and that the adjusted R2 is 78.4 percent. We also find that both the performance pay (t = 34.044, p = 0.000) and BTA bias (t = −3.057, p = 0.000) are statistically significant, while gender (t = 0.114, p = 0.909) and length of work experience (t = −0.492, p = 0.623) are not statistically significant. The positive coefficient value for performance pay suggests that as performance pay increases, POS will also increase. This finding provides support for Hypothesis 1. The statistically significant negative coefficient of BTA bias confirms the existence of an inverse relationship between BTA bias and POS, and provides support for Hypothesis 1. Correlational analysis, which is an equivalent approach to testing Hypotheses 1 and 2, provides exactly the same results (see Table 4).

| Unstandardized (Standardized) Beta's | t-value | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Pay | 9.049 (0.773) | 34.044 | 0.000 |

| BTA Bias | −0.043 (−0.103) | −3.057 | 0.000 |

| Length of Work Experience (months) | −0.013 (−0.013) | −0.492 | 0.623 |

| Gender | 0.031 (0.003) | 0.114 | 0.909 |

| N = 324 | 293.883 | 0.000 | |

| df1 =4 | df2 = 319 | ||

| Adj. R2 = 0.784 |

Notes:

- Dependent variable = POS.

- Gender = Dummy Variable (0 = male, 1 = female).

- Performance Pay: Dummy Variable (0 = $500 (lower relative pay); 1 = $1,500 (higher relative pay)).

- *Reported p-values are for 2-tailed tests.

| Correlation table | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Pay | BTA Bias | Gender | Work Experience | Performance Outcome Satisfaction | ||

| Performance Pay | Pearson Correlation | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.88 |

| p-value | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | ||

| N | 328 | 328 | 328 | 324 | 328 | |

| BTA Bias | Pearson Correlation | 1.00 | −0.05 | 0.14 | −0.11 | |

| p-value | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.05 | |||

| N | 328 | 328 | 324 | 328 | ||

| Gender | Pearson Correlation | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | ||

| p-value | 0.45 | 0.87 | ||||

| N | 328 | 324 | 328 | |||

| Work Experience | Pearson Correlation | 1.00 | 0.03 | |||

| p-value | 0.63 | |||||

| N | 324 | 324 | ||||

| Performance Outcome Satisfaction | Pearson Correlation | 1.00 | ||||

| p-value | ||||||

| N | 328 | |||||

To test Hypothesis 3, we expanded the previous model to include an interaction variable between performance pay and BTA bias; the model is shown below.

The regression results in Table 5 indicate that the model is statistically significant (F = 237.631, p = 0.000), and the adjusted R2 is 78.6 percent. We find a significant main effect for both performance pay (t = 2.842, p = 0.005) and BTA bias (t = −4.113, p = 0.000)). We also find a moderately statistically significant interaction effect (t = 1.866, p = 0.063). Gender (t = 0.114, p = 0.909) and length of work experience (t = −0.494, p = 0.662) are not statistically significant. Our results for the interaction term provide modest support for Hypothesis 3. The result suggests that the negative impact of BTA bias on POS is somewhat tempered by the level of performance pay.

| Unstandardized (Standardized) Beta's | t-value | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Pay | 5.484 (0.534) | 2.842 | 0.005 |

| BTA Bias in Comparison to their Immediate Work Associate | −0.063 (−0.151) | −4.113 | 0.000 |

| Length of Work Experience (months) | −0.013 (−0.013) | −0.494 | 0.622 |

| Gender | 0.031 (0.003) | 0.114 | 0.909 |

| Interaction Between Performance Pay and BTA Bias | 0.040 (0.343) | 1.866 | 0.063 |

| N = 324 | F = 237.631 | 0.000 | |

| df1 = 5 | df2 = 318 | ||

| Adj. R2 = 0.786 |

Notes:

- Dependent variable = POS.

- Gender = Dummy Variable (0 = male, 1 = female).

- Performance Pay Dummy Variable (0 = $500 (lower relative pay); 1 = $1,500 (higher relative pay)).

- *Reported p-values are for 2-tailed tests.

A more detailed analysis suggests that the difference between the satisfaction levels reported by the high BTA group and the low BTA group is lower under the “high relative performance pay” condition as compared to the same difference under the “low relative performance pay” condition. In other words the difference in POS levels for the high BTA and the low BTA groups, although present, is not as pronounced under the “high relative performance pay” condition compared to the “low relative performance pay” condition. This finding supports our hypothesis that performance pay is a moderating variable that influences the relationship between BTA bias and POS.

Additional Tests

| Performance pay is less than their immediate work associate | Performance pay is more than their immediate work associate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized (Standardized) Beta's | t-value | p-value* | Unstandardized (Standardized) Beta's | t-value | p-value* | |

| BTA Bias | −0.065 (−0.405) | −5.663 | 0.000 | −0.021 (−0.091) | −1.150 | 0.252 |

| Length of Work Experience (months) | 0.005 (0.012) | 0.165 | 0.87 | −0.031 (−0.055) | −0.699 | 0.486 |

| −0.906 (−0.225) | −3.173 | 0.002 | 0.968 (0.168) | 2.155 | 0.033 | |

| N = 162 | F = 13.870 | 0.000 | N = 162 | F = 2.245 | 0.085 | |

| df1 = 3 | df2 = 158 | df1 = 3 | df2 = 158 | |||

| Adj. R2 = 0.193 | Adj. R2 = 0.023 | |||||

Notes:

- Dependent Variable = POS.

- Gender: Dummy Variable (0 = male, 1 = female).

- *Reported p-values are for 2-tailed tests.

Table 6 indicates that BTA bias significantly influences POS (t = −5.663, p = 0.000) in the condition where the relative performance pay is less than that of the immediate work associate. We also find a significant effect for gender (t = −3.178, p = 0.002), suggesting that females are less satisfied relative to their male counterparts when the amount of performance pay received is less than their immediate work associate. The overall model is statistically significant (F = 13.870, p = 0.000), with an adjusted R2 of 19.3 percent.

However, the test results shown in Table 6, for the condition where the relative performance pay is more than that of the immediate work associate, reveal that BTA bias does not have a statistically significant effect on POS (t = −1.150, p = 0.252). Similar to the previous test, we found a significant effect for gender (t = 2.155, p = 0.033), suggesting that females are more satisfied relative to their male counterparts when the amount of performance pay received is more than their immediate work associate. We found this model to be moderately significant (F = 2.245, p = 0.085), and the adjusted R2 was 2.3 percent.

A comparison of the above two results suggests an explanation for the moderate significance of the interaction variable. Providing a relatively higher performance pay somewhat mitigates the impact of BTA on POS. It would appear that when the relative performance pay is larger it has the ability to confirm an individual's perception that they are better than average, thereby reducing the negative impact of BTA bias on POS. Collectively our results strongly support Hypothesis 1; the important point here is that when an individual is rewarded less than his or her immediate work associate (proxied by the relative performance pay), he or she is less satisfied with his or her performance outcome (i.e., satisfaction with his or her performance evaluation and with his or her performance pay). Our results also strongly support Hypothesis 2, thereby suggesting that when an individual perceives their relative ability to contribute, proxied by their BTA bias, as being higher, he or she will be less satisfied with his or her performance outcome.

A question that may arise regarding our POS construct is whether an individual is likely to rate their performance evaluation satisfaction as high (low) and their performance pay satisfaction as low (high). This question could arise because participants provided separate responses to each aspect of the overall performance evaluation. To examine for the possibility of such an occurrence, we computed the Pearson correlation between the two satisfaction ratings. Should individuals rate one of their satisfaction scores high (low) and the other as low (high), the Pearson correlations should not be significant. The Pearson correlations, between satisfaction with performance evaluation and satisfaction with performance pay under the two conditions of performance pay, show that in the condition where performance pay is lower (higher) than that of the immediate work associate, the correlation coefficient was 0.458 (0.570). Both coefficients are statistically significant at the 1 percent level (p = 0.01). This finding reinforces the use of a single variable, POS, by combining the two separate but related components.

In addition to the correlation analysis, we tabulated the number of participants who provided similar satisfaction ratings for each component of performance evaluation. The results, in Tables 7 and 8, show that the subjects are clustered in two groups: those who are satisfied with both components and those who are dissatisfied with both components. In the condition where pay was less than that of their immediate work associate, 94 percent of the subjects were generally dissatisfied with both their performance evaluation and the amount of their performance pay. Similarly, in the condition where pay was greater than that of their immediate work associate, 70 percent of the subjects were, by and large, satisfied with both their performance evaluation and the amount of their performance pay. The combined results provide further support for our use of the POS variable.

| Performance Evaluation Satisfaction | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 = Very Dissatisfied | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 = Very Satisfied | Total | ||

| Performance Pay Satisfaction | 0 = Very Dissatisfied | 33 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 |

| 1 | 12 | 18 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43 | |

| 2 | 17 | 6 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48 | |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | |

| 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 = Very Satisfied | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 68 | 40 | 39 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 164 | |

| Performance Evaluation Satisfaction | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 = Very Dissatisfied | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 = Very Satisfied | Total | ||

| Performance Pay Satifaction | 0 = Very Dissatisfied | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 24 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 38 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 14 | 11 | 5 | 5 | 39 | |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 23 | |

| 8 = Very Satisfied | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 18 | 36 | |

| Total | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 32 | 51 | 29 | 22 | 25 | 164 | |

Discussion

Our study focused on the link between an individual's perceived ability to contribute relative to his or her peers (operationalized as BTA bias) and the individual's satisfaction with the outcomes of the performance evaluation process (i.e., with the evaluation as well as the associated reward); we operationalized this construct as performance outcome satisfaction (POS). We also examined the impact of performance pay upon that link. The use of BTA bias as a proxy for an individual's relative ability to contribute is an important methodological contribution of this study. We are not aware of any other study that has examined the relationship between BTA bias and POS or the moderating effect of relative performance pay (RPP) upon that link.

We found that, in general, our participants (i.e., entry-level accountants), rated themselves as better than the average audit professional and their immediate work associate. We also found that both BTA bias and RPP individually influenced POS; finally we found a moderately significant interaction effect. In their entirety, the results indicate that the greater entry-level accountants believe they are better than average, the more likely their performance outcome satisfaction will fall, although this negative impact can be mitigated by using higher relative performance pay.

The implications of each hypothesis for accounting firms and management accountants are as follows. Finding support for Hypothesis 1 implies that when accountants receive a larger relative performance pay, other things held equal, there will be an increase in their level of POS. Consequently one would infer that for accountants (the employees), relative performance pay matters, since for these individuals a large relative reward is effectively acknowledging their contributions and confirming their high expectations.

The importance of Hypothesis 2 is that it draws attention to the role of an intangible factor—BTA bias—in determining POS. Empirical support for Hypothesis 2 is a signal for an accounting firm hoping for high levels of POS among the employees from its performance evaluations and pay for performance programs to recognize that POS is being influenced by its employees' BTA bias. If the performance evaluation and compensation processes ignore the BTA bias, then it is highly likely that the performance outcomes resulting from the organization's performance evaluation process will be inconsistent with the expectations of the employees and low levels of POS (and potentially job satisfaction) will result. In other words Hypothesis 2 may provide an explanation for an accounting firm that is experiencing low levels of POS and job satisfaction among its employees.

But what comfort is there to be had in the knowledge that the performance outcome satisfaction among employees is being influenced in part by factors external to management control systems? What is management to do in such situations? This is a challenging question for accounting firms. Since the perceptions that are formed by employees are about their own abilities relative to that of peers, one strategy for managers and management control systems designers wishing for employees to experience high levels of POS and job satisfaction will be to attempt to influence the formation of such perceptions and expectations. This can be possible if management creates opportunities for employees to understand better their individual capabilities as well as those of their peers. Whether or not management can provide such opportunities is an open question. Our findings for Hypotheses 1 and 3 may offer a potential (although different) solution.

The key hypothesis for our paper is Hypothesis 3. The finding of a moderately significant positive interaction effect is evidence that relative performance pay mitigates the negative influence of BTA bias on POS and amplifies the positive influence of relative performance pay on POS. Such a finding would be relevant to management since it reveals relative performance pay as one tangible factor that can be used to counter the negative influence of BTA bias. As well, it suggests that for employees who have high self-efficacy, high relative performance pay will reduce the negative effect of BTA bias on POS. Given our assertion that accounting firms are examples of organizations where such employees will be prevalent, support for Hypothesis 3 is a clear indication that relative performance pay matters to accountants and that accounting firms should care about the amount of performance pay they dispense to their employees. In other words relative performance pay can become a strategic tool by which management can seek to establish higher levels of POS and job satisfaction among the employees, especially when those employees have high levels of self-efficacy exhibited through high levels of BTA bias.

If self-assessments and the use of performance pay in accounting firms influence POS for entry-level accountants, as suggested by our research, the implication is that firms should strive to avoid incongruences between the expectations that employees form based on their sense that they are better than average and the performance evaluation and subsequent rewards being provided to them. If the outcome of the performance evaluation and reward is congruent with the expectations formed by employees, it can result in improved POS. Since expectations are unobservable it poses a major challenge for firms as to the steps that can be taken to close the gap between employee expectations and the performance outcome. Our finding that performance pay mitigates the BTA bias on POS suggests that performance pay can become a management tool to diminish the lack of congruency that might otherwise exist.

The preceding suggests an interesting direction for future research: to study the scope for directly confronting the BTA phenomenon during the performance evaluation process or even through periodic communication. Given that communication between employees and senior management has been ranked as one of the most important factors affecting job satisfaction (SHRM, 2012), it is tempting to conclude from our work that if a firm were to communicate to its employees during the performance evaluation process a rationale that directly focused on the employee's sense of BTA, it may provide the employee the opportunity to revise their sense of BTA and thereby rationalize their evaluation and subsequent reward. More specifically this would likely lead to a more realistic assessment of satisfaction compared to what it would have otherwise been. Our research does not test this conjecture; however, it can form the basis of a future study.

A related issue is the potential benefit to firms to preempt the BTA formation process in its employees by directly managing the formation of BTA bias in employees. Through ongoing feedback and mentoring and training, it may be possible for firms to reduce BTA bias among its employees, thereby managing individual expectations. Following from expectancy theory, a change in one's self-efficacy should lead to a change in expectations. Perhaps one way of reducing this bias is to create an environment where high levels of interaction exist among peers. Alicke (1985) and Alicke et al. (1995) also state that BTA scores will fall (i.e., become smaller) as the peer group becomes better defined—going from a wider peer group to a more specific one (our results corroborate these findings). Miceli and Lane (1991) suggest that a critical component in equity theory is the selection of the peer group; they state that any individuals comparing themselves to a peer must perceive the target as being similar. Therefore, organizations that encourage mutual collaboration and teamwork can expect individual employees to alter their perceptions, relative to peers, due to the fact that individuals have a better understanding of their peers' abilities relative to themselves. Consequently an important future direction for research in this area suggested by our study is to investigate how firms might manage BTA formation in its employees and to test if BTA bias can be reduced and whether the BTA effect on POS can be overcome.

Our study is not without limitations. Our first limitation is the use of questionnaires/surveys and cases to collect information. Case studies may not adequately reflect the impact of actual, real-world performance pay differences. Simply stated, if individuals know that the performance pay differences and performance appraisal results are not real, but rather only fictitious, questions designed to investigate satisfaction levels may not reflect the participants' actual degree of (dis)satisfaction.

A second limitation of our study relates to the problems associated with self-evaluations. The self-evaluation questionnaires/surveys used in our research are subject to participants providing answers that they may perceive as either socially desirable (thus reducing BTA bias) or what they believe the researcher is trying to find (thus inflating BTA bias). Either of these conditions could bias the results.

A third limitation of our study stems from the small sample size. Although conducting an experiment in a controlled setting (i.e., classroom) provides certain types and levels of control, it also limits us from generalizing the results of the study to populations other than the one being represented by our participants. A fourth and final limitation in our study relates to the ability to design reasonable survey questions and cases that adequately probe performance outcome satisfaction levels, while balancing between using instruments that are too complex and not overly transparent. Although a number of steps were taken to develop and implement a questionnaire/survey and cases that addresses both challenges, it should be noted that they are not without their inherent risks.

In summary, the results of our study are important to the accounting profession because they fill a gap—both in the accounting literature and at the operations or practical level—for any accounting firms using or contemplating the use of performance pay. Our study provides accounting firms, their partners, managers, and employees with valuable information regarding the influence of performance pay and self-assessments upon POS.