Lung squamous cell carcinoma with brachial soft tissue metastasis responsive to gefitinib: Report of a rare case

Correspondence

Eiji Osaka, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Nihon University School of Medicine, 30-1 Oyaguchikami-cho, Tokyo 173-8610, Japan.

Tel: +81 33 972 8111

Fax: +81 33 972 4824

Email: [email protected]

Abstract

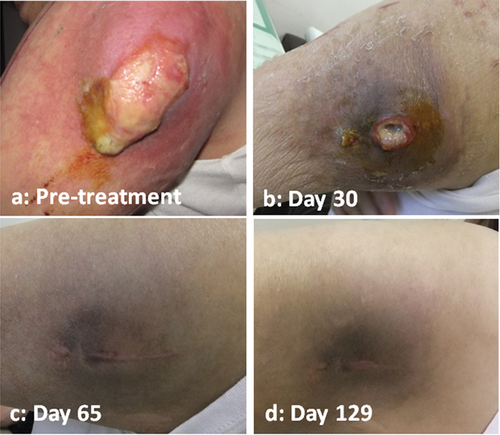

Metastasis of lung cancer to soft tissue is rare and patient outcomes are generally poor. There are no reports describing soft tissue metastasis in lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), in which gefitinib treatment was effective not only for the primary tumor but also the metastatic lesion. A 61-year-old Asian woman presented to our facility with pain and a mass in the brachium. An additional tumor was identified in the lung. As we suspected soft tissue metastasis of lung cancer, an incisional biopsy was performed, yielding a diagnosis of SCC. The brachial tumor continued to grow and became exposed at the biopsy site when the incisional wound dehisced. Because the biopsied specimen was positive for an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene mutation, we commenced gefitinib administration. This treatment resulted in the rapid shrinkage of both the brachial metastasis and the primary tumor, followed by healing of the wound. Therefore, tyrosine kinase inhibitors should be used for cases that present EGFR activating mutations independently from the presence of skin and soft tissue metastases.

Introduction

While lung cancer often metastasizes to the liver, brain, bone, and lymph nodes, metastasis to soft tissues is rare. Soft tissue metastasis is generally detected at an advanced stage, and prognosis in these patients is quite poor.1 If the malignant tumor exposed on the skin continues to grow, possibly even becoming exposed on the skin surface as a result of biopsy wound dehiscence, as in our present case, the patient's quality of life will likely be markedly reduced because of pain, bleeding, and exudation from the tumor-affected area. There is no standard method of local treatment for such cases, and management is often difficult. There are no published reports describing soft tissue metastasis from lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in which gefitinib was effective not only for the primary tumor but also the metastatic lesion.

Case report

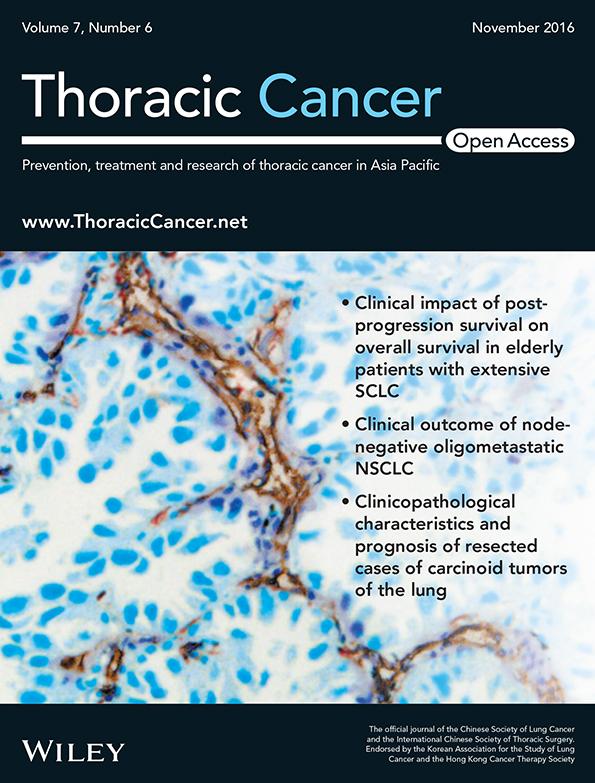

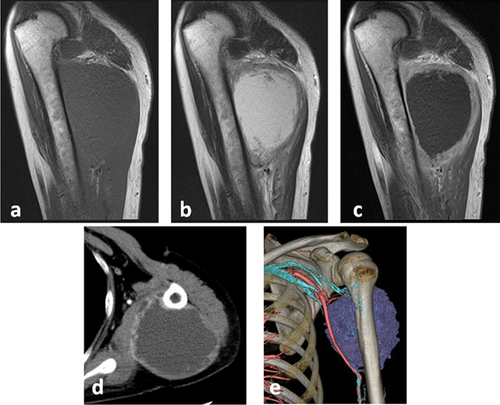

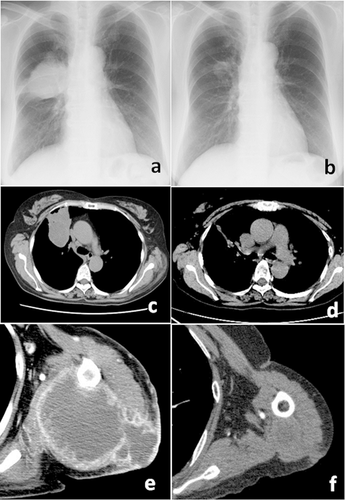

A 61-year-old Asian woman consulted our facility for left brachial pain and a mass that had developed approximately a month prior to the current presentation. Her past medical history was unremarkable, with no history of either malignant disease or smoking. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a mass within the triceps muscle of the brachium (Fig 1a–c). Computed tomography (CT) showed a tumor adjacent to the humerus, accompanied by venous invasion and compression of the brachial artery (Fig 1d,e). A needle biopsy of the soft tissue mass yielded a class V cytological diagnosis and raised suspicion of SCC. Based on a suspicion of brachial soft tissue metastasis, a detailed examination of the primary tumor was conducted, resulting in the detection of an infiltrative shadow in the lung on chest radiography and CT scan (Fig 2a,c). An incisional biopsy was performed for definitive diagnosis and genetic testing. The patient was diagnosed with soft tissue metastasis from lung SCC (Fig 3a,b). After biopsy, the brachial tumor continued to grow, eventually causing dehiscence of the incisional wound, leading to a secondary infection, such that administration of chemotherapy was not possible (Figs 2e, 4a). Local radiotherapy was ineffective. Thus, we considered amputation. However, the pathological examination revealed a mutation (point mutation in exon 21 L858R) in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene. Based on this finding, oral gefitinib administration was started. This treatment resulted in the rapid shrinkage of the brachial and pulmonary tumors (Fig 2a–f). Following these reductions in tumor size, the incisional wound from the biopsy healed spontaneously (Fig 4a–d). At present, approximately 15 months after the start of gefitinib treatment, marked shrinkage of the brachial and pulmonary tumors has been maintained on diagnostic imaging and the patient has followed a favorable course without exacerbation (Fig 2b,d,f).

Discussion

Although the muscles are rich in blood flow, metastasis to muscle tissues is rare, with reported incidences of soft tissue metastasis from lung cancer ranging from 0–0.8%.1-3 Soft tissue metastasis is only detected at advanced stages in many patients, resulting in a poor prognosis.1 Although chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy are widely used for treating soft tissue metastasis, no clearly effective means of treatment is currently available.

Epidermal growth factor receptor is a transmembrane receptor protein containing tyrosine kinase that transmits signals involved in cell proliferation. EGFR is activated in many malignancies, including lung cancer, and gefitinib inhibits the proliferation of cancerous cells through the inhibition of EGFR tyrosine kinase.4 Gefitinib has been reported to significantly extend the progression-free survival period compared with conventional chemotherapy.5-8 Although EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, including gefitinib, have been effectively used for the treatment of lung cancer with EGFR mutations, most patients become drug resistant within a few years. Recent studies have shown that resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer is involved in various mechanisms, including T790M mutation and MET amplification.9 Because of the potential for developing gefitinib resistance, careful follow-up is essential. The percentage of cancers positive for EGFR gene mutations varies depending on factors such as histological type, race, and gender, with about 30% of lung adenocarcinomas in Japanese positive for EGFR gene mutations. In most cases, the histological type of lung cancer is adenocarcinoma. The mutation rate in SCC cases is quite low (0–5%); thus, gefitinib is unlikely to be effective for most SCC cases.10 Soft tissue metastasis of lung SCC responding to gefitinib, as seen in the present case, is an exceedingly rare event.

In patients with malignant tumor exposure on the skin, quality of life is markedly reduced because of pain, bleeding, and exudation from the tumor-affected area. Pain can result from many causes, including tumor invasion to the nerves and dressing changes. In many cases, using the best painkiller or changing dressing methods can relieve pain. Bleeding is often dealt with by topical ethanol injection or compressive hemostasis, but bleeding tends to reoccur, making hemostasis difficult. Furthermore, infections develop in many cases, resulting in exudation and requiring numerous daily bandage changes. There is no standard for local treatment in such cases, and management is generally challenging. Gefitinib delays but does not completely inhibit wound healing.11 The wound in the present case healed without further intervention following tumor shrinkage (Fig 2a–f). We advocate that molecular-targeted drugs be actively used for the management of skin-exposed tumors with EGFR gene mutations.

This case highlights regression of both a primary lung SCC and soft tissue metastasis, which had become exposed on the skin as a result of growth and biopsy wound dehiscence, in response to gefitinib. Careful follow-up is essential because of the potential for developing gefitinib resistance.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Shunzo Osaka (Orthopaedic Surgery of Nihon University Hospital) for manuscript editing.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.