Radiotherapy in nonagenarian patients: A 20-year retrospective analysis in a single ternary centre

A Katano: MD, PhD; H Yamashita MD, PhD.

Abstract

Introduction

The global burden of cancer and the ageing population is increasing, resulting in an increase in cancer incidence among elderly patients. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes and safety profile of radiotherapy in nonagenarians and to contribute to the existing knowledge on radiotherapy in elderly patients.

Methods

This retrospective analysis included nonagenarian patients who received external beam radiotherapy at a single centre in Japan between May 2003 and May 2023. Data, including patient demographics, tumour characteristics, treatment details, and clinical outcomes, were collected from medical records. Statistical analyses including survival and subgroup analyses were performed to summarize the data.

Results

The analysis included 124 nonagenarian patients who received 151 treatment courses. Among the patients with a median age of 92 years (range, 90–98 years), 71 received palliative-intent radiotherapy and 53 underwent curative-intent radiotherapy. The overall survival rates at 1 and 3 years after radiotherapy were 55.4% and 38.3%, respectively. Performance status and radiotherapy at the primary site were independent prognosis factors for improved overall survival, while age was not. The incidence rate of grades 3–5 radiation-related toxicities was 3.4%, which is generally considered to be acceptable.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that radiotherapy can be effectively and safely used in this age group, supporting its use as a treatment option for both palliative and curative goals. These results contribute to the existing body of evidence on radiotherapy in elderly patients and can guide clinical decision-making in the management of nonagenarian patients with cancer.

Introduction

The global burden of the ageing population is growing rapidly and is an important medical problem worldwide.1 By 2050, the number of elderly people aged over 60 years will reach 2.1 billion, which will be larger than that of young adolescents.2 The global cancer incidence rate is 19.3 million per year, which has been increasing over the years owing to the ageing population.3 Japan is one of the most elderly countries in the world, and the number of nonagenarians has been steadily increasing.4 Despite the increasing incidence of cancer among elderly patients, the collaboration between oncologists and geriatricians is limited.5 Moreover, despite the fact that elderly patients account for the majority of cancer patients, clinical evidence for treating elderly patients is limited owing to their underrepresentation in many clinical trials.6 Current guidelines and treatment protocols are often based on studies involving relatively young patients, and the applicability of such approaches to nonagenarians remains uncertain.7 This knowledge gap underscores the need for further research focused on older patients to better inform their treatment decisions and improve the outcomes in this age group.

Radiotherapy is a crucial treatment modality for cancer, and more than half of cancer patients require radiotherapy as part of cancer treatment.8 Radiotherapy is an excellent treatment option for older adults with cancer owing to its effectiveness, low systemic toxicity, convenience, and tolerability.9 However, evidence on the outcomes and safety of radiotherapy is limited, particularly in elderly patients. No definitive evidence supports any universal criteria for radiation tolerance as age increases.10 Recent advancements in modern radiation techniques have significantly reduced both immediate and delayed side effects, thereby expanding the treatment options available to elderly or frail patients and allowing for higher treatment intensities.11 Therefore, it is crucial to understand the efficacy and potential risks associated with radiotherapy in nonagenarians, especially elderly patients, in order to optimize cancer treatment decisions and improve patient care. According to an analysis of data from the National Cancer Database conducted by Yang et al.,12 the majority (57.6%) of the nonagenarian patients with non-small cell lung cancer did not receive any cancer therapy. However, in a subset analysis of this cohort, stage I patients who underwent surgery showed better 5-year survival rates than the non-therapy group (33.7% vs 6.1). They also insisted that treatment strategies for nonagenarian patients should be based on clinical stage and patient preferences in a multidisciplinary setting.

This study aimed to comprehensively evaluate the clinical outcomes and safety profile of radiotherapy in nonagenarians at a single centre in Japan. By examining a cohort of nonagenarian patients who underwent radiotherapy, we aimed to provide a detailed assessment of disease control, overall survival, and treatment-related toxicities in this specific age group. Furthermore, the findings of this study can contribute to the existing body of evidence on radiotherapy in elderly patients and help guide clinical decision-making in the management of nonagenarian patients with cancer. This research has the potential to fill the current knowledge gap by offering insights into the effectiveness and safety of radiotherapy in this unique patient population. Overall, a retrospective analysis of radiotherapy outcomes in nonagenarians can provide valuable information to clinicians, enabling them to make evidence-based treatment decisions tailored to the specific needs and characteristics of this age group. Additionally, the results of this study may serve as a foundation for future prospective investigations and the development of specialized treatment guidelines for nonagenarians receiving radiotherapy.

Methods

Study design

This study employed a retrospective analytical design to investigate the use of radiotherapy in nonagenarian patients in Japan. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes and treatment efficacy in this specific age group. The study was conducted at a single centre, and data were obtained from medical records. This study was conducted at a tertiary cancer centre in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the single centre. Patient confidentiality and data protection were ensured throughout this study.

This study included nonagenarian patients who received external beam radiotherapy at our department as part of their cancer treatment between May 2003 and May 2023. The study population included patients with histologically or clinically confirmed malignancies who were administered external beam radiotherapy with various fractionation schedules, depending on the disease site and treatment intent. Patients who were lost to follow-up immediately after radiotherapy were excluded, and three patients who underwent only brachytherapy and eight patients who received gamma knife treatment were also excluded. Data were collected on various variables, including patient demographics, tumour characteristics, treatment details, and clinical outcomes. Relevant information was extracted from electronic medical records, including patient age, sex, tumour type and stage, treatment protocols, radiation doses, survival outcomes, locoregional or metastatic status of the disease, intent of radiotherapy treatment, and treatment-related adverse events.

The intent of radiotherapy was either curative when the intent was to completely eradicate the disease or palliative when the aim was to relieve the patients' symptoms. The curative radiotherapy protocol included definitive and adjuvant settings after surgery, such as those used for locally advanced soft tissue sarcoma and malignant glioma after surgery. Radiotherapy protocols used for nonagenarian patients were reviewed and documented, namely the type of radiation technique, treatment planning, radiation doses, and fractionation schedules.

The primary clinical outcome of interest was overall survival (OS). OS was defined as the time from the start of radiotherapy to the date of death or last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) rates after curative-intent radiotherapy were based on the time from the start of radiotherapy to the date of death or clinical relapse, as assessed by radiological imaging or clinical evaluations, considering parameters such as tumour size, regression, and absence of recurrence.

Statistical analysis was used to summarize patient demographics, tumour characteristics, treatment details, and clinical outcomes. A t-test was used to compare the means of continuous variables between the two groups. The chi-square test was used to determine statistically significant differences in categorical variables between the two groups. Survival analysis, including the Kaplan–Meier curves, was used to estimate the OS and PFS. Subgroup analyses were conducted to assess potential associations between clinical outcomes and patient or tumour characteristics. Statistical analyses were performed using appropriate software, and P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 124 nonagenarian patients who underwent 151 treatment courses were included in this retrospective analysis. For the 151 treatment courses, the median prescribed total radiation therapy dose was 30 Gy (range, 8–70 Gy) in seven fractions (range, 1–35). Among 151 treatment courses, 117 radiotherapy treatment courses (77.4%) consisted of no more than 10 fractions, and the planned prescribed radiotherapy courses were completed in 147 treatment courses. The backgrounds of the 124 patients are presented in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 92 years (range, 90–98 years); 71 patients received palliative-intent radiotherapy, and 53 patients underwent curative-intent radiotherapy. The patients in the curative radiotherapy arm had a slightly younger mean age (mean: 91.5 vs 92.3 years, P = 0.0387) with a male-dominant background (male-to-female ratio: 2.31 vs 0.78, P = 0.0067) than those in the palliative-intent radiotherapy arm.

| Variables | Total number (%), N = 144 | Curative (%), n = 53 | Palliative (%), n = 71 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: median [range] | 92 [90–98] | 91 [90–97] | 92 [90–98] | 0.0387 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 68 (55%) | 37 (70%) | 31 (44%) | 0.0067 |

| Female | 56 (45%) | 16 (30%) | 40 (56%) | |

| Karnofsky performance status | ||||

| 90 | 30 (24%) | 23 (43%) | 7 (10%) | 0.0002 |

| 80 | 46 (37%) | 20 (38%) | 26 (37%) | |

| 70 | 25 (20%) | 6 (11%) | 19 (27%) | |

| 60 | 11 (9%) | 2 (4%) | 9 (13%) | |

| 50 | 11 (9%) | 2 (4%) | 9 (13%) | |

| 40 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Primary disease | ||||

| Lung | 21 (17%) | 16 (30%) | 5 (7%) | 0.0040 |

| Skin | 14 (11%) | 4 (8%) | 10 (14%) | |

| Haematological disorder | 14 (11%) | 2 (4%) | 12 (17%) | |

| Prostate | 12 (10%) | 8 (15%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Oesophagus | 7 (6%) | 3 (6%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Oral cavity | 7 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 6 (8%) | |

| Others | 49 (40%) | 19 (36%) | 30 (42%) | |

| Site of radiation therapy | ||||

| Primary | 88 (71%) | 48 (91%) | 40 (56%) | 0.0008 |

| Regional lymph node | 7 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 6 (8%) | |

| Distant metastasis | 20 (16%) | 2 (4%) | 18 (25%) | |

| Combination of above | 9 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 7 (10%) | |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| Outpatient | 85 (69%) | 41 (77%) | 44 (62%) | 0.1030 |

| Inpatient | 39 (31%) | 12 (23%) | 27 (38%) | |

| Pathology | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 36 (29%) | 12 (23%) | 24 (34%) | 0.0049 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 21 (17%) | 13 (25%) | 8 (11%) | |

| Lymphoma | 11 (9%) | 2 (4%) | 9 (13%) | |

| Others | 56 (45%) | 27 (51%) | 29 (41%) | |

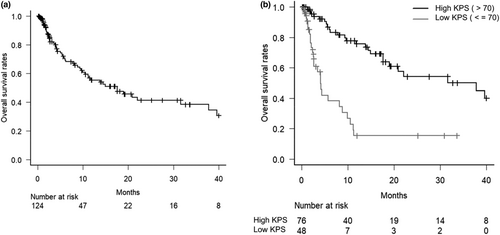

For the entire cohort, the 1-year OS and 3-year OS after radiotherapy were 55.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 44.3–65.2%) and 38.3% (95% CI: 26.2–50.2%), respectively (Fig. 1). Cox proportional hazards regression analyses for OS were conducted to identify the prognostic factors (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis, radiotherapy to the primary site (HR = 2.228, 95% CI: 1.175–4.224, P = 0.014) and performance status (HR = 5.264, 95% CI: 2.788–9.936, P < 0.001) were independently associated with increased overall survival, while age was not an independent significant prognostic factor (HR = 1.978, 95% CI: 0.933–4.193, P = 0.075). Figure 1b shows the Kaplan–Meier curves of patients stratified by performance status. The median OS was significantly worse in the poor performance status group than in the good performance status group (4.1 vs 37.8 months, P < 0.001).

| Covariables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | ||||||

| <95 vs ≥95 years old | 2.6790 | 1.323–5.427 | 0.0062 | 1.978 | 0.933–4.193 | 0.0751 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male vs Female | 1.2970 | 0.754–2.228 | 0.3473 | 0.970 | 0.544–1.731 | 0.9189 |

| Performance status | ||||||

| >70% vs ≤70% | 4.6390 | 2.592–8.303 | <0.0001 | 5.264 | 2.788–9.936 | <0.0001 |

| Primary disease | ||||||

| Lung vs others | 2.0740 | 0.863–4.988 | 0.1032 | 2.274 | 1.018–5.084 | 0.0452 |

| Treatment site | ||||||

| Primary vs others | 1.8000 | 1.014–3.196 | 0.0446 | 2.228 | 1.175–4.224 | 0.0141 |

| Pathology | ||||||

| SqCC vs others | 0.7464 | 0.417–1.335 | 0.3239 | 0.968 | 0.524–1.788 | 0.9174 |

- CI, confidence interval; SqCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

In the curative-intent radiotherapy group, 53 patients were treated with a total of 56 courses because three patients underwent curative-intent radiotherapy. The median number of prescribed radiotherapy fractions was seven (range, 4–35), with a median single-fraction dose of 5 Gy (range, 2–13.75 Gy) and a median total dose of 55 Gy (range, 25–70 Gy). All but one course of radiotherapy were completed as planned.

The most common malignancies treated with curative intent were lung cancer (n = 16), prostate cancer (n = 8), and bladder cancer (n = 5). Among 53 patients, 25 patients (48.0%) underwent stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT); all patients with lung and prostate cancers were treated with SBRT. Six patients received concurrent systemic therapy with radiotherapy, and the most frequent primary cancers treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy were bladder cancer (n = 3), followed by glioma (n = 2), and skin cancer (n = 1). Details of the treatments are presented in Table 3.

| Primary disease | Number (%) | SBRT | RT alone | CCRT | Median total dose [range] (Gy) | Median fraction [range] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 16 (30) | 16 | – | – | 55 [42–56] | 4 [4–7] |

| Prostate | 8 (15) | 8 | – | – | 40 [36.25–42.5] | 5 [5–5] |

| Bladder | 5 (9) | – | 2 | 3 | 60 [60–60] | 30 [30–30] |

| Glioma | 4 (8) | – | 2 | 2 | 41 [25–42] | 11 [5–15] |

| Skin | 4 (8) | – | 3 | 1 | 60 [45–60] | 30 [15–30] |

| Neck | 4 (8) | – | 4 | – | 62 [50–70] | 25 [10–35] |

| Oesophagus | 3 (6) | – | 3 | – | 66 [50–66] | 30 [25–33] |

| Liver | 2 (4) | – | 2 | – | 50 [50–50] | 10 [10–10] |

| Sarcoma | 2 (4) | – | 2 | – | 55 [50–60] | 25 [20–30] |

| Lymphoma | 2 (4) | – | 2 | – | 40 [30–50] | 20 [15–25] |

| Oral cavity | 1 (2) | – | 1 | – | 66 | 33 |

| Vagina | 1 (2) | – | 1 | – | 50 | 25 |

| Oligometastasis (Lung) | 1 (2) | 1 | – | – | 55 | 4 |

| Total | 53 (100) | 25 | 22 | 6 |

- CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; RT, radiotherapy alone; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy.

The 3-year OS and PFS after curative-intent radiotherapy were 59.9% (95% CI: 40.9–74.5%) and 54.0% (95% CI: 36.9–68.4%), respectively. Among 13 patients with relapsed disease after curative radiotherapy during our analysis period, only two patients chose salvage therapy (one was surgery, and the other was systemic therapy administration), and the other 11 patients chose no further cancer treatment and received the best supportive care.

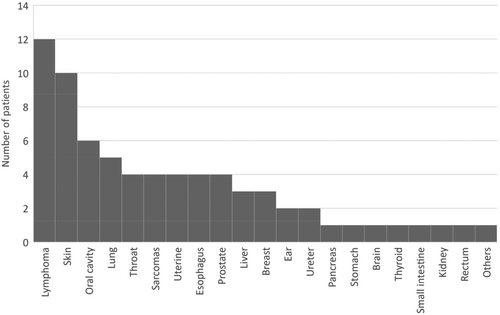

Furthermore, 71 patients who received palliative-intent radiotherapy in 95 treatment courses were included in the analysis. The median number of treatment courses per patient was 1 (range, 1–5). The majority of the palliative radiotherapy schedules were 30 Gy in 10 fractions (32 courses), 20 Gy in 10 fractions (16 courses), and 8 Gy in one fraction (24 courses), all accounting for 75.8% of the palliative treatment course (Table 4). The median OS after palliative radiotherapy was 5.4 months (95% CI: 3.4–11.1 months). A wide variety of primary diseases were treated with palliative radiotherapy, with haematological cancer (12 patients) followed by skin cancer (10 patients) and oral cavity cancer (6 patients) being the most frequent (Fig. 2).

| Variables | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 30 Gy/10 Fr | 32 | 32 (34) |

| 8 Gy/1 Fr | 24 | 24 (25) |

| 20 Gy/5 Fr | 16 | 16 (17) |

| 39 Gy/13 Fr | 4 | 4 (4) |

| 40 Gy/20 Fr | 4 | 4 (4) |

| 16 Gy/2 Fr | 3 | 3 (3) |

| 35 Gy/5 Fr | 2 | 2 (2) |

| 20 Gy/10 Fr | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 20 Gy/4 Fr | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 25 Gy/10 Fr | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 25 Gy/5 Fr | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 33 Gy/11 Fr | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 35 Gy/14 Fr | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 50 Gy/25 Fr | 1 | 1 (1) |

| Uncompleted cases | 3 | 3 (3) |

Acute-phase radiation-related toxicities were observed in 42 patients who received radiotherapy, with the most common toxicity being grade 1–2 dermatitis in 28 patients. Grade 3 or higher toxicities were observed in two patients in the acute phase: grade 3 dermatitis after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for skin cancer and grade 5 radiation pneumonitis after lung SBRT. Grade 3 or higher late adverse events were observed in two patients: grade 3 and grade 5 toxicity radiation pneumonitis after lung SBRT. No acute grade 3–5 adverse events were observed in the palliative radiotherapy group. Overall, among the 124 nonagenarian patients who received radiotherapy, four patients (3.2%) developed grade 3–5 radiation-related toxicity.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the outcomes and toxicities associated with radiotherapy in nonagenarian patients. Radiation therapy treatment was well tolerated, with a 3.2% rate of grade 3 or higher adverse events rate for the entire cohort. Our results demonstrate that both palliative- and curative-intent radiotherapy can be safely administered to this age group, with acceptable treatment response rates and manageable toxicities. These findings support the use of radiotherapy as a viable treatment option for nonagenarian patients with both palliative and curative goals and are compatible with those of previous studies.

Sprave et al.13 examined the feasibility and outcomes of radiotherapy in 119 nonagenarian patients with cancer. They reported a 3-year OS of 11.1%, which was relatively low compared to that in our study, given the relatively high rate of palliative-intent cases at 68.1%. Regarding the number of fractions, the median value was relatively large at 14, resulting in a high discontinuation rate of initially planned radiotherapy in 16.8% of the cohort. Kocik et al.14 conducted a retrospective study to investigate the feasibility of radiotherapy in 93 nonagenarians. In their patient cohort, 85% of the patients completed their prescribed radiotherapy course, with only 4% having grade 3 or higher adverse events. The median survival was significantly longer in patients treated with curative radiotherapy than in those treated with palliative radiotherapy (13.8 vs 3.6 months). Ikeda et al.15 conducted a retrospective survey to examine the application of curative radiotherapy in 57 nonagenarian patients at eight institutions between 1990 and 1995. The completion rate of their treatment was 75%, emphasizing the importance of familial support in assisting elderly patients during their daily radiotherapy sessions.

Patients treated with definitive or adjuvant radiotherapy had a significantly higher median survival rate than those treated with palliative radiotherapy. Previous studies revealed favourable clinical outcomes of curative-intent radiotherapy with tolerable toxicity in elderly patients. Nakanishi et al.16 retrospectively investigated the clinical data of patients aged ≥75 years old with prostate cancer who underwent curative-intent radiotherapy, resulting in a 5-year OS of 87.9%, with a median follow-up time of 83.5 months. They also reported low cumulative incidence rates of grade 3 or higher genitourinary and gastrointestinal toxicities of 3.3% and 3.5% at 7 years, respectively. Watanabe et al. evaluated the effectiveness of SBRT in 64 elderly patients aged 80 years with early-cell lung cancer. They reported good clinical outcomes, with a 3-year OS rate of 68.3% and grade 3–5 adverse events observed in only three patients.17

In the palliative-intent radiotherapy group, no grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events were observed in the present study. The median OS after palliative radiotherapy was 5.3 months, comparable to that of the general population. Krishnan et al.18 retrospectively reviewed 862 patients with metastatic cancer who received palliative radiotherapy and reported a median survival of 5.6 months. Zaorsky et al.19 analysed data from the National Cancer Database of 68,505 patients who underwent palliative radiotherapy between 2010 and 2014. Their results showed that the median survival time after palliative radiotherapy was 5.1 months for the medium-risk groups.

Our results revealed that performance status was the most significant factor for OS, suggesting that chronological age alone may not be a limiting factor when considering radiotherapy in nonagenarians. Rühle et al.,20 in their study of octogenarian cancer patients with bone metastases receiving palliative radiotherapy, reported that performance status was an independent prognostic factor in the multivariate analysis for OS, but age was not. However, performance status, which is widely used in oncological treatment planning, is insufficient to assess functional impairment in elderly patients.21 Jolly et al.22 found that geriatric assessment, based on performance status, used in geriatric medicine could be useful in decision-making for cancer treatment in elderly patients who are considered functionally normal. There have been attempts to validate the role of geriatric assessment in radiation oncology to correlate with oncologic outcomes and toxicities.

It is worth noting that our study has several limitations. First, its retrospective nature introduced inherent biases and limitations in data collection. Second, because this was a single-centre study, the generalizability of our findings may be limited. Multicentre studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate our results and provide more robust evidence. Third, this study could not include enough data on comorbidity index and frailty scores, so further additional research is needed in this area. Additionally, the lack of a control group and heterogeneity of tumour types and treatment regimens limit our ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the comparative effectiveness of radiotherapy in nonagenarians.

Despite these limitations, our study contributes to the existing body of evidence regarding the use of radiotherapy in nonagenarians and highlights the potential benefits and acceptable toxicities associated with both palliative- and curative-intent radiotherapy in this age group. These findings support the consideration of radiotherapy as an important treatment modality for nonagenarians, offering the potential for symptom relief, disease control, and improved quality of life.

In conclusion, our retrospective analysis demonstrated that radiotherapy with both palliative and curative intent can be safely and effectively performed in nonagenarian patients. The observed treatment responses and manageable toxicities underscore the importance of individualized treatment planning and close monitoring. Further research is needed to refine treatment strategies, optimize patient selection, and enhance outcomes in this unique and growing patient population.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Research

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.