MRπ: Inside the meat pie

Summary

Meat pies have been adopted as one of Australia's favourite foods, and considered an icon by many. The hand-held convenience of the pie has made them a culinary necessity while watching sport, also beloved in Australia. An enduring question about the meat pie is what exactly is inside. This can be difficult to ascertain by digital, ocular or oral exploration. In this study we use MR imaging to study the contents of some of Australia's best loved pies.

Video Byte

MRπ: Inside the meat pie

by Massie et al.Introduction

Meat pies are an Aussie institution and a distinctively Australian cuisine 1. It is quite possible that the pie was invented by First Australians who lived on this continent from 65,0000 years ago, but a lack of written or drawn evidence makes this claim hard to substantiate 2. This is a pity, because the X-ray art of First Australians might have solved this enduring puzzle well before now.

The Egyptians are credited with the proto-pie, their bakers incorporating nuts, honey and fruit in a bread dough 3. Credit for the invention of the meat pie (and curiously π) goes to the Greeks who made a pie-like dish of meat (probably lamb) wrapped in pastry. Perhaps all the plates had been broken and the pastry casing made a handy serving vessel. The Romans took home this pie recipe as a spoil of war, typically copying Greek culture and claiming it as their own. This just adds weight to the well-known criticism of ancient Rome, ‘What have the Romans ever done for us?’ Pies are said to have spread through Europe along the ancient Roman roads, so perhaps we do have something to be grateful to the Romans for after all. Pies were popular dishes in England through the Middle Ages. While many meats were used, magpie was a favourite and is likely to be the etymological origin of the name, ‘pie’.

It is very likely meat pies were brought to Australia with the First Fleet. One of the earliest records of pie selling in the colony of NSW is English migrant William King (the ‘Flying Pieman’) who sold pies to ferry passengers at Circular Quay 4. The precise origin of commercial meat pie production in Australia is contested. This is an important thing for Australians to argue about, and not surprisingly claims fall along state lines. Pie manufacturer Sargent (Sydney, NSW) is recorded making a pie from 1891 5. Balfour's (South Australia) opened in 1853, but the precise time of pie making remains unclear, but claimed ‘for over 100 years’ 6. In Victoria it is well established that that L.T. McClure produced an Aussie pie at his small bakery in Bendigo in 1947 1. These were the forerunners of the now iconic Four ‘N'Twenty pies. It would be positively un'Strayan not to eat one of these at a sporting gathering. To cope with the multicultural diversity of modern Australia vegetarian and Halal versions of pies are available, although whether a Kosher version is available remans unclear. The hand held convenience of the meat pie has been part of its enduring appeal and more recently there have been moves to elevate the humble meat pie from merely food to cuisine. Leaving the modern adaptions aside, an enduring question about meat pies that has fuelled much speculation and ended in many unsavoury disagreements, is what exactly is inside an Aussie meat pie?

To answer this question and reduce the workload of Emergency Departments after a sporting match we returned to the First Australian concept of X-ray vision and decided to look inside the great Aussie meat pie using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology.

Methods

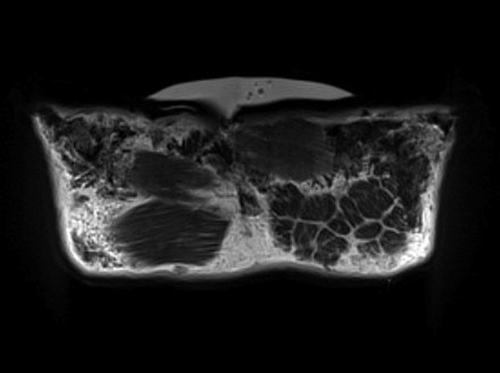

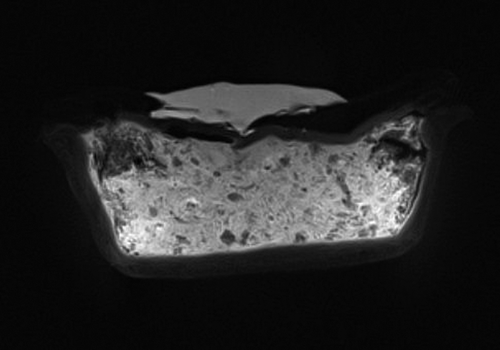

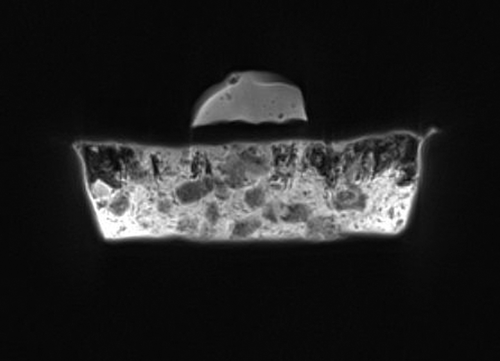

We selected two meat pies that have become popular across Australia (Four n'Twenty, Bocastle) and a regular winner of the Australian meat pie competition (The Rolling Pin, Ocean Grove Victoria). To determine the characteristics of the contents inside the pies, we used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Siemans, Melbourne, Vic., Australia). To maintain anonymity we randomly assigned a study number to each pie. Pie demographics (circumference and area measured at the mid plane) were recorded from MR measurements. We looked for the presence of chunky pieces and graded these on a ‘Like-it’ scale of 0 (none) to 3 (big). The quality of meat was assessed by the presence of muscle fibres detected in the chunks. We measured the diameter of the chunky pieces. To understand the effect of tomato sauce on top we performed T(omato)-weighted images of each pie. To standardize sauce application we used an individual ‘squeezy’ tomato sauce dispenser by one researcher (MK).

The study was not approved by an institutional ethics committee. The human research ethics committee did not consider a pie to be human so felt this project did not fall under their jurisdiction. Tellingly, the animal research ethics committee was of similar opinion (i.e. the meat pie had nothing to do with animals!). We offered a cut of the pie to the chair of each group but they were immune to our inducements. This was a fortunate development as we estimated that the time taken to develop the study, perform the scans, analyse the data and write the manuscript would be about 1/10th the time for an ethics application, which is about standard for modern research. No seriously ill children had to wait very long for a scan while the research was conducted. No pies were harmed during the research.

Funding for the study was shamelessly solicited from each company manufacturing the pies, but unsuccessful. The pies were purchased from loose coins taken from the pockets of children attending our institution for MRI scans. This was done for their safety and to teach them the value of donating to medical research.

Results

The images of each pie are shown in Figures 1-3. The results of the pie analysis are presented in the Table 1. Owing to the limitations of MRI technology, it was not possible to accurately distinguish the elements of the non-chunky pieces in the pie. We were hoping to present a meat:gravy ratio, but subjectivity of such an analysis rendered this unscientific. Similarly it was not possible to determine fat from meat using MR signals. The pastry encasing could be seen, but it was not possible to measure the thickness with certainty.

| Pie characteristic | Pie A | Pie B | Pie C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Area (mm2) | 3005 | 2338 | 1723 |

| Perimeter (mm) | 256 | 234 | 202 |

| Visible chunks | ✔✔✔ | ✔ | ✔✔ |

| Maximum size of meat chunk (mm) | 36.4 | 7.2 | 18.9 |

| Muscle fibre identifiable | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ |

Discussion

We have shown that the meat content of the Aussie meat pie varies greatly. Some pies have large, obviously animal muscle derived pieces, whereas for others there are smaller pieces of less distinct origin. There was also considerable variation in the size of the pies that were all sold as individual use items. All of the pies were encased in pastry of similar consistency, but MRI did not allow for measurement of thickness with sufficient scientific rigour to report in this journal. The tomato sauce formed a pleasing blob on the top of the pie, without seeming to penetrate the pastry. Standard medical MRI was not helpful in determining the characteristics of the non-solid meat contents of the pies.

Magnetic resonance imaging has been used by the food industry to investigate the conditions required for producing pork pie jellies with different properties 7. This work may be of relevance to those living in the Australian Capital Territory where pork pies are more commonly peddled.

Magnetic resonance imaging has also been used to create artistic images of fruit 8. While appreciating the artistic merits of such images, we cannot condone such a frivolous use of expensive MRI technology that has limited availability to people with medical illness. Such misuse of resource is unethical and should be deplored.

Magnetic resonance imaging was also used to create an image of the 70th birthday cake of the inventor of medical magnetic resonance technology, Dr PC Lauterbur 9. Individual banana and peach slices were clearly visible, but the nature of the material between (presumably cake mix) was not. This just goes to show what we all know about radiologists; they want to have their images and eat them too.

There are some limitations of our study. Owing to resource limitations (we had $26.65 raided from children's pockets) we could only afford to purchase three varieties of Aussie meat pie. The MRI signals could not be used to distinguish the non-meat characteristics of the pie contents. This turns out to be a fortunate limitation of the technology as the pies can be consumed without having to worry about fat content. Similarly, MRI proved somewhat flakey when it came to measuring pastry thickness.

Having established the utility of MRI in determining some useful characteristics of the contents of the iconic Aussie meat pie it would be good to use MRI to study other Australian icons. MRI could be used to identify the contents of the football (all codes) and the kangaroo (just as soon as we can tie one down). Owing to a combination of manufacturing moving offsite and metal content, we would not be able to use MRI on Holden cars.