Malignant hyperechoic breast lesions at ultrasound: A pictorial essay

Summary

Malignant breast lesions are typically hypoechoic at sonography. However, a small subgroup of hyperechoic malignant breast lesions is encountered in clinical practice. We present a pictorial essay of a number of different hyperechoic breast malignancies with mammographic, sonographic and histopathologic correlation. Suspicious sonographic features in a hyperechoic lesion include inhomogeneity in echogenic pattern, an irregular margin, posterior acoustic shadowing and internal vascularity. A hyperechoic lesion at ultrasound does not discount the need to undertake histological assessment of a mammographically suspicious lesion.

Introduction

On ultrasound, a hyperechoic breast mass is defined as a lesion that is of increased echogenicity compared to the subcutaneous adipose tissues. Approximately 0.6–5.6% of breast masses are hyperechoic.1-3 In 1995, Stavros et al.1 described lesions that were uniformly hyperechoic with no isoechoic or hypoechoic areas as benign, reporting a negative predictive value of 100% after 42 biopsies of hyperechoic nodules. One of the most common benign hyperechoic breast lesion is fat necrosis from previous breast trauma. Other benign entities include lesions containing adipose tissue (lipoma), lesions containing fibrotic tissue (pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia and others), vascular lesions (haemangioma) and a combination of tissue types such as a hamartoma and angiomyolipoma. A number of authors have published data indicating that a very small proportion of hyperechoic lesions are malignant. Linda et al.2 reported 9 (0.5%) hyperechoic malignant lesions out of 1849 biopsied malignancies. Nam et al.3 reported 103 hyperechoic lesions out of 16416, of which 27 were biopsied, five (4.9%) were malignant, and Soon et al.4 found two (0.5%) hyperechoic nodules among 393 screen detected breast cancers.

Background

The cases in this pictorial essay are patients that were referred to the breast assessment centre at Royal Perth Hospital from 2011 to 2015.

Primary breast carcinoma

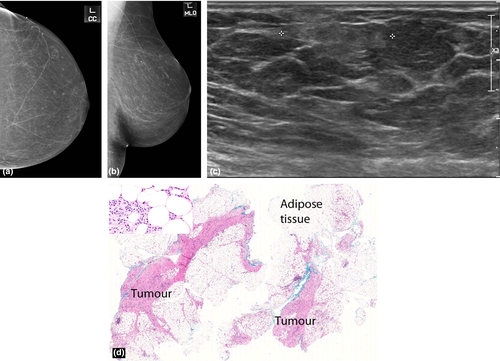

Invasive ductal carcinoma

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) is the most common invasive primary breast malignancy. Clinically, the carcinoma may present as a palpable mass with features such as skin retraction and nipple discharge, or as an assymptomatic screen detected lesion.

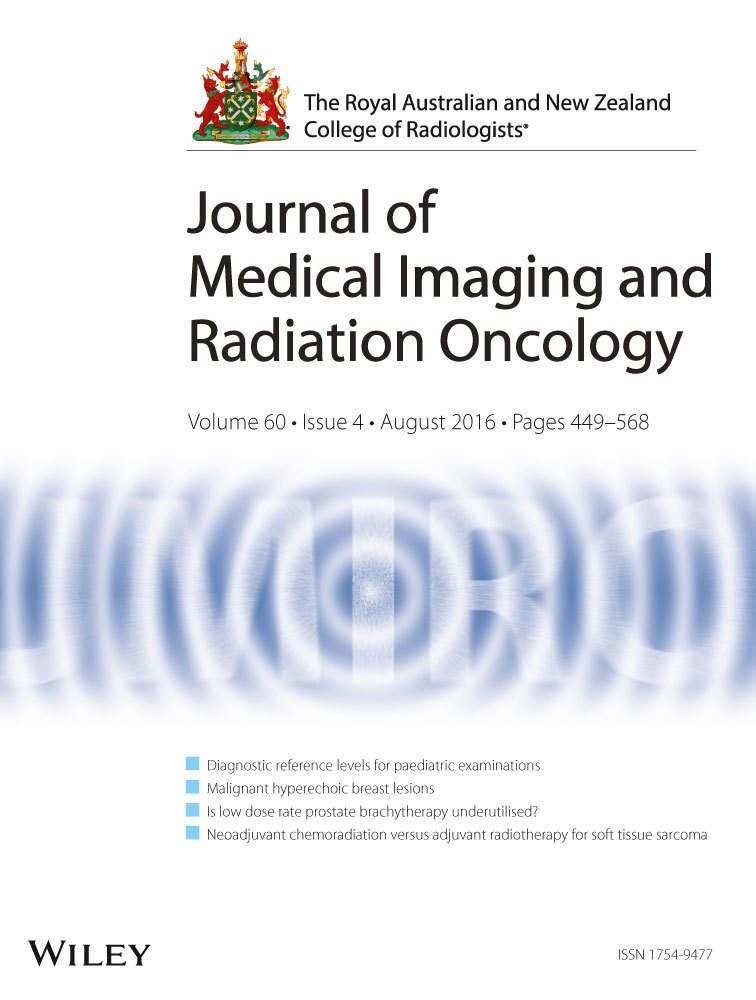

The characteristic mammographic appearances are of an irregular, spiculated mass (Fig. 1a) with or without pleomorphic calcifications and architectural distortion. The typical sonographic appearance of a primary breast malignancy is that of a hypoechoic mass with irregular margins and variable posterior acoustic shadowing.

Malignant hyperechoic lesions are more likely than benign lesions to have an irregular shape (Fig. 1-3), non-parallel orientation and a hypoechoic component.2, 3 A lesion that is not completely hyperechoic and has small hypoechoic areas should be regarded as suspicious.1, 2 Other predictive features of malignancy include a spiculated shape, posterior shadowing and distortion of surrounding tissues3 (Fig. 1-3).

Nam et al.3 reported that all five hyperechoic carcinomas had corresponding suspicious mammographic findings such as spiculated margins, interval enlargement, suspicious microcalcification and lymphadenopathy.

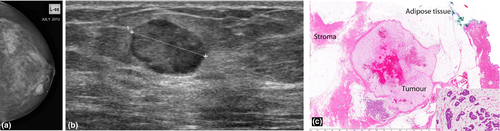

Invasive lobular carcinoma

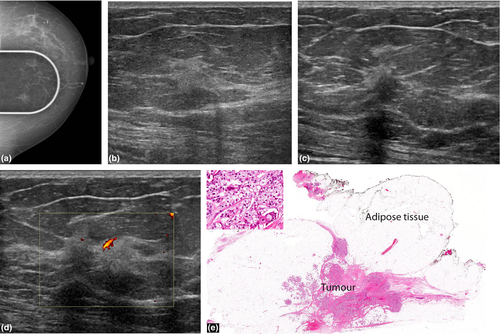

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is a tumour composed of small, usually bland cells arranged in poorly cohesive aggregates or in single files surrounding ducts and not destroying normal parenchyma, with minimal desmoplastic response. The commonest appearance on mammography is a spiculated mass. However, many present as an isolated architectural distortion or focal asymmetry or are seen on one mammographic view (Fig. 5) only or are radiographically occult. On ultrasound, they are usually hypoechoic with typical suspicious features of irregular margins and posterior acoustic shadowing (Fig. 4, 5).

The literature suggests that hyperechoic malignancies may be more commonly associated with ILC.4-6 In a series by Cawson et al.6, 21 (57%) out of the 37 ILCs were at least partly hyperechoic, concluding that ILC was 9.94 times more likely to be hyperechoic than IDC. Waterman et al.6 who studied sonographic appearances of 406 invasive breast carcinomas reported that a hyperechoic or isoechoic pattern was more frequent in ILC. Jones et al.7 conducted a retrospective review of 509 ILCs and concluded that 27 (5%) were hyperechoic. The periductal infiltration by ILCs with formation of concentric rings may act as acoustic reflectors5 causing the bright hyperehoic halo around the small hypoechoic tumour nidus to become the predominant ultrasound finding.

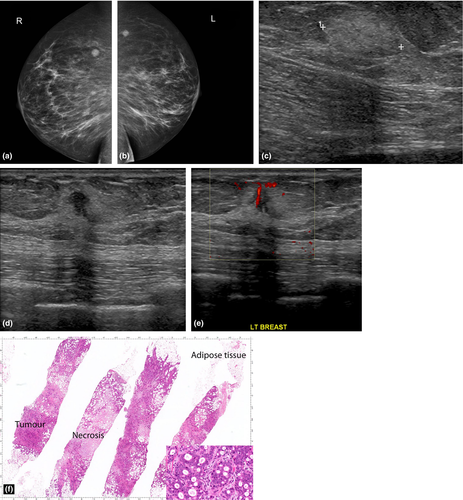

Mucinous (colloid) carcinoma

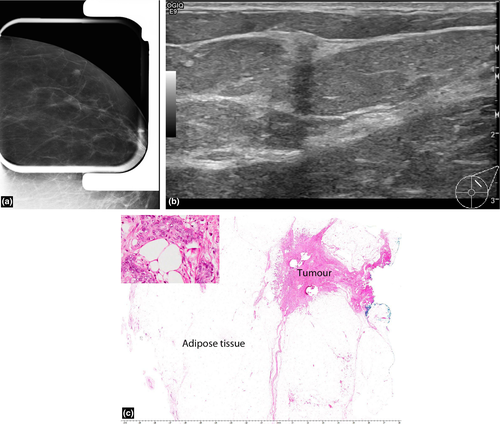

This is an uncommon breast malignancy which comprises 0.5–3% of breast carcinomas.8 These mucin producing tumours can be pure or mixed, with the pure subtype conferring a better prognosis. Microscopically, the tumour cells occur within large mucinous lakes which may result in a core biopsy finding of mucinous pools with a paucicellular tumour.

On mammography, the tumour may be round, oval, irregular or dense with circumscribed or partially indistinct margins (Fig. 6a). On sonography (Fig. 6b), the tumour is frequently isoechoic or hypoechoic to surrounding adipose tissues but may occasionally be hyperechoic.8 Because of their wide ranging appearances and occasional well-defined margins, they may mimic a fibroadenoma or hamartoma. Posterior enhancement is a common association and posterior shadowing is rare (Fig. 6b). A homogeneous appearance to the lesion is usually associated with a pure subtype and conversely lesional heterogeneity at ultrasound is more predictive of a mixed subtype.8

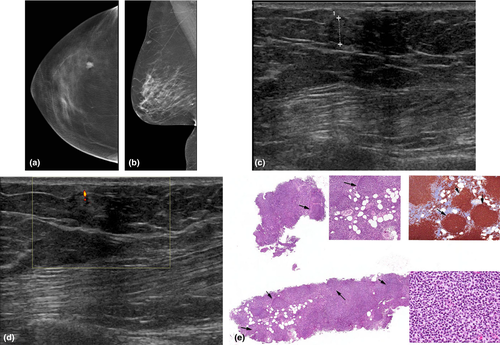

Metastasis

Metastases to the breast are uncommon but should be considered as a differential diagnosis for multiple breast masses in the setting of a known malignancy. The commonest malignancies that metastasize to the breast are melanoma (skin) and lung adenocarcinoma.9 Other primaries to consider include small cell carcinoma, sarcoma, neuroendocrine tumours and squamous cell carcinomas. Rarely metastases may originate from a contralateral breast primary.

When the tumour spread is haematogeneous, the mammographic findings include round, circumscribed, non-calcified masses (Fig. 7a). If the spread is lymphangitic, there may be breast enlargement, skin thickening, asymmetric density and axillary adenopathy. Although metastases to the breast are most commonly hypoechoic, they can rarely present as hyperechoic masses (Fig. 7c). Lesional hypervascularity is seen in the majority of melanoma metastases.8

Lymphoma

Breast lymphoma is the second most common (after melanoma) non-mammary malignancy of the breast. Breast lymphoma may be primary or secondary. The diagnostic criteria for primary breast lymphoma include the breast as the site of clinical presentation of the disease, absence of prior lymphoma or absence of widespread disease at diagnosis, close association of mammary tissue with lymphomatous infiltrate and disease limited to the breast and/or ipsilateral lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis.10 Secondary breast lymphoma occurs in setting of systemic lymphoma.

The mammographic appearance is usually a solitary, non-calcified mass with no overt spiculation (Fig. 8a,b). In secondary breast lymphoma, axillary adenopathy is a common mammographic presentation, with asymmetry of the breast and skin thickening. On sonography, the appearance is variable, ranging from hypoechoic, mixed echogenicity to near completely hyperechoic lesions11 (Fig. 8c). There is usually marked vascular flow9 in the lymphoma mass.

Pitfalls for detection

Stavros et al.1 recommended that a lesion should be homogeneous in echogenicity and more hyperechoic than adipose tissue for it to be considered benign on ultrasound.

Some infiltrating malignancies can have a small hypoechoic central nidus surrounded by a larger hyperechoic halo. Scanning through the thick hyperechoic halo and not appreciating the hypoechoic central focus can cause such lesions to be misinterpreted as purely hyperechoic.12

In conclusion, approximately 0.5%2, 11 of malignant breast lesions appear hyperechoic. Correlation with mammographic findings and clinical history should determine the need for biopsy. A hyperechoic lesion in the absence of a preceding history of trauma and characteristic mammographic radiolucent appearances of fat necrosis may ultimately require a biopsy for a definitive assessment.