Traffic pollution near childcare centres in Melbourne

Correction added on 14 August 2019, after first online publication: the second sentence under ‘Siting of childcare centres in Melbourne’ has been updated to correct 14% to 10.4%, as indicated by the symbol ᶺ.

Australia’s most common cause of general practitioner presentation in children under five is asthma and allergy. There is increasing evidence that exposure to traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) is a significant contributor to the prevalence of asthma and allergy, and proximity to major roads correlates with exposure to TRAP. Childcare is an integral part of society where many children pass a significant amount of time. The siting of childcare centres is therefore a critical consideration for the healthy development of children and should be an important factor in urban growth planning.

A study conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) has found 90% of the world’s children are breathing toxic air, exceeding WHO Air Quality Guidelines.1 Australian air quality generally falls within WHO guidelines; however, there are hot spots in Australia – including Melbourne – that exceed legislated thresholds.2 Furthermore, conclusive evidence that there is no safe lower limit to the adverse effects of traffic pollution has brought the safety of these guidelines into question. A critical consideration for planning and health authorities should be to ensure the cleanest possible air for all people.

Children are particularly vulnerable to TRAP due to the adverse effects on lung development. Furthermore, children spend more time outdoors than adults, leading to higher exposures. Many independent groups have linked acute and chronic respiratory illnesses in children to exposure to outdoor air pollution.3-5 In 2012, Gasana et al.6 conducted a large meta-analysis of children with asthma and motor vehicle pollution. The authors observed that children living or attending schools near high traffic density roads were exposed to higher levels of vehicle pollutants; nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, airborne particles (particulate matter) and ozone had an associated increase in the incidence and prevalence of childhood asthma and wheeze.

A meta-analysis by Bowatte et al. in 2015 discovered that for every 2 µg/m3 incremental increase in chronic exposure to traffic-related particulate matter, the risk of developing subsequent asthma in childhood increased by 14%.7 Furthermore, increased exposure was associated with sensitisation to both airborne and food allergens.7 In 2016, the same group used a birth cohort of 620 high-risk infants from the Melbourne Atopy Cohort Study.8 They defined traffic-related air pollution exposure during the first year of life as the cumulative length of major roads within 150 m of each participant’s residence. The authors observed that carriers of genetic polymorphisms in the glutathione S-transferase (GST) were more susceptible to the impacts of traffic pollution. In GSTT1 null carriers, every 100 m increase in cumulative lengths of major road exposure during the first year of life was associated with a 2.31–fold increased risk of wheeze and a 2.15–fold increased risk of asthma at 12 years.8

Additional to lung health, a recent Brisbane study examining school children’s exposure to TRAP found a positive association with biomarkers for systemic inflammation, indicating the likelihood of extra-pulmonary impacts.9

Siting of childcare centres in Melbourne

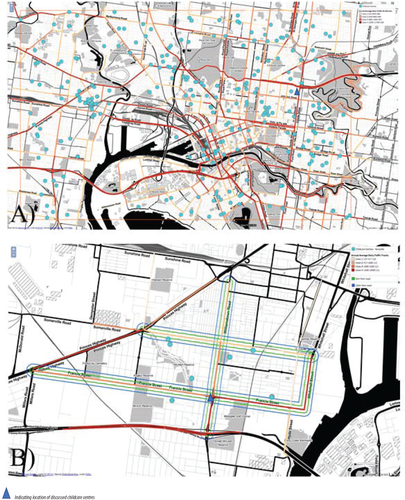

Based on the aforementioned evidence, we are concerned about current planning recommendations in Melbourne that actively encourage the placement of childcare centres in proximity to main roads. An analysis of childcare locations and road vehicle density in inner-city Melbourne revealed that, of the 278 childcare centres, 10.4% (29 centres) were within 60 metres of a major road.ᶺ This is in sharp contrast with Californian guidelines that recommend a 150-metre buffer between schools and major roads.10

An example that raised our concern is provided by an inner-Melbourne childcare centre, situated 15 metres from a busy eight-lane road (Figure 1A). In 2013, the Victorian EPA using measurements from the nearest static monitor (3 km away), reported a fine particulate matter annual average of 6.8 µg/m3 for this area, thereby falling under the federal and state health-based annual average threshold of 8 µg/m3. Independent hourly measurements by Ecotech Pty Ltd for three months (April – June) in 2014 revealed a seasonal average of 11.4 µg/m3 with two exceedances of the hourly threshold of 25 µg/m3 (28.4 µg/m3 and 37.8 µg/m3). If the seasonal average is indicative of the annual average, and it is valid to apply the odds ratio from the Bowatte meta-analysis to the children in this childcare centre, the additional 4.6 µg/m3 of traffic-generated fine particulate matter is associated with a 35% increase in the relative risk of developing childhood asthma.

Maps of (A) metropolitan region of Melbourne and its average daily traffic (including all traffic); (B) Yarraville with 50m and 100m distances from roads shown; including average daily trucks.

Source: VicRoads, G. o. V.-. Traffic Volume (Polyline) 2017. 2017 ed.; https://portal.aurin.org.au 2018.

We are also concerned about a childcare centre under current development in Yarraville, an inner-western suburb of Melbourne that has the highest rate of emergency hospital presentations for paediatric respiratory disease in Victoria.11, 12 Yarraville is situated between the port of Melbourne and container yards and consequently an estimated 20,000 trucks and cars pass through its streets daily (Figure 1B).13, 14 Previous EPA monitoring of roadside pollutants in this suburb has shown exceedances of air quality thresholds.14 The childcare centre will be situated on an intersection used by a daily average of 4,650 trucks.13 Four metres will separate the children in this centre from the trucks with an open-air playground planned for the second level that will place children at the same height as truck exhaust pipes. This centre would not meet the Californian guidelines, and we question the regard given to the health of the future occupants during the planning process.

Benefits of improved air quality/planning recommendations

In 2015, Gauderman et al. demonstrated significant health improvements associated with the Californian EPA policies that reduced children’s exposure to TRAP over two decades.5 The authors correlated the reduction in air pollution levels with significant improvement in lung function over three cohorts of children (n=2,120) during the time periods 1994–1998, 1997–2001 and 2007–2011.5 In both children with or without asthma declining levels of TRAP was associated with significant improvements in lung function. Gauderman’s study demonstrated that the Californian EPA policies resulted in the development of larger, healthier lungs in children, with health benefits that extend into adulthood, including a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and associated mortality.15-17

Recommended action

Victorian policy makers should implement the world’s best practice mitigation strategies established by the Californian EPA as soon as possible. Our findings show nearly one-quarter of childcare centres in Melbourne are within 150 metres of a major road, exposing young Australians to unnecessary levels of TRAP and the associated health impacts. While we acknowledge the introduction of buffer zones could potentially create impracticalities and counter other policies, the long-term health benefits can be expected to pay off. We urge policy makers to adopt the international best practice mitigation strategies that, in addition to buffer zones, include:

- indoor ventilation and filtration

- anti-idling and idle reduction policies

- roadside barriers

- designing outdoor play-areas away from TRAP flow movements

- play-time structured to avoid peak traffic hours

- encouragement of active transportation.

The monitoring and reporting of air quality around sensitive sites such as childcare centres also requires action. Air quality monitoring networks across Australia historically consist of static monitors located to measure ‘ambient background levels’ of air pollutants. As illustrated by the inner-suburban Melbourne childcare centres, this approach is unlikely to accurately reflect population exposure due to the spatial variability across the urban landscape. It also fails to account for the toxic chemical composition of traffic-related particles that are likely to contribute to the health risks associated with proximity to traffic.18 The emergence of low-cost air quality monitoring systems provides an opportunity for centres to install their own air quality monitoring system, with real-time data allowing the implementation of immediate mitigation strategies when required.

Lung health and development in children holds lifelong consequences. Health professionals must play an active role in raising public awareness and advocating for greater consideration of children’s lung health in childcare centres.

Future urbanisation, population growth and reliance on vehicles implies an increasing number of children will become highly exposed to TRAP. Australian-specific trends including projected increases in airborne particulates and ground-level ozone; increasing dieselisation of the vehicle fleet; and the higher content of sulphur in petrol may negate improvements related to international advancements in vehicle pollution technology. Our National Environmental Protection Measures legislation is underpinned by the objective that “all Australians enjoy the benefit of equivalent protection from air pollution”19 yet, until we follow international examples and actively seek to reduce children’s exposure to traffic pollution, we are failing our most vulnerable members of society.

Acknowledgements

Clare Walter and Elena Schneider-Futschik are joint first authors of this paper.

The authors acknowledge support from Philip Greenwood (Melbourne eResearch Group) for accessing and producing the maps used in the figure from the Australian Urban Research Infrastructure Network (AURIN). Accessed 29 November 2018.

Elena Schneider-Futschik is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council.