Cultural immersion: Embedding Torres Strait Islander (Melanesian) history, culture, diet and health in dietetics curricula

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley - The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Abstract

Aims

To describe a Torres Strait (Melanesian) cultural immersion delivered to dietetics students at a large university in Australia and to understand whether cultural immersion supports the development of students' knowledge and skills in relation to specific Dietitians Australia performance criteria.

Methods

The cultural immersion was co-designed, analysed, and reported through an iterative process with a Torres Strait immersion educator from the Eastern Islands, a First Nations researcher, and a dietetics academic. The cultural immersion included an opening ceremony, four station rotations of creation stories through weaving; food preparation; artefacts and cultural dance; and yarning about health, as well as a closing ceremony. A mixed methods approach was used. Data from pre- and post-surveys were analysed with Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test or paired t-test, and integrated with the thematic analysis of focus group interviews to provide context, depth and perspectives.

Results

Forty-eight students completed pre- and post-surveys, and 25 participated in focus groups. Through working at the knowledge interface, students' general knowledge on Torres Strait Islander history, culture, diet and health increased (all p < 0.001). The cultural immersion supported the development of competence through reframing the narrative and experiential learning, impacted their journey as dietitians by promoting reflection, and increased their perceived confidence in working with Torres Strait Islander populations in a health setting.

Conclusions

This cultural immersion enriched dietetics students' understanding of Torres Strait Islander history, culture, diet, and health. Cultural immersion is one teaching method that can be used within an integrated suite of education strategies to support the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health competencies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples both represent the First Nations people of Australia. Torres Strait Islander peoples are the Traditional Owners of at least 274 islands and the reefs in the straits between the Cape York Peninsula and Papua New Guinea.1 The Islands are clustered into five main groups based on geography and cultural characteristics, with communities also residing in coastal areas of northwestern Cape York Peninsula and mainland Australia.2 Kalaw Lagaw Ya (Australian) and Meriam Mir (Papuan) are distinct Indigenous languages, with Yumplatok (Torres Strait Creole) being commonly spoken. Rooted in Melanesian cultural heritage with Austronesian and European influences,3 the peoples of the Torres Straits are a smaller and distinct cultural group that is often underrepresented within First Nations academia and research.4 They proudly represent unique Ailan Kastoms (Island Customs), culture, spiritual beliefs, ceremonial dances, languages, songs, and vibrant arts, which reflect a relational connection to sea, land, winds, and sky.5 For Torres Strait Islander people, health and wellbeing are holistic concepts, influenced by interconnected physical, social, cultural, spiritual, and ecological factors.6 Ensuring that Torres Strait Island culture is also acknowledged and celebrated within the university curriculum is an important process to enable future health professionals to provide culturally appropriate and effective services. An Aboriginal cultural immersion we conducted highlighted this important need to recognise Torres Strait Islander peoples' culture, linguistics, customs and belief systems, to enrich students' understanding of both of Australia's First Nation cultural groups within dietetics education.7

The Dietitians Australia (DA) Accreditation Standards for Dietetics Education Programs,8 requires universities to be responsible for ensuring that their curricula and assessment strategies align with the National Competency Standards for Dietitians.9 The National Competency Standards consist of four domains, with each domain containing specific elements (12 in total), and within these elements, there are 55 performance criteria. Four performance criteria explicitly relate to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.9 Two separate Accreditation Standards stipulate that institutions integrate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples' history, health, and wellbeing across the curriculum (standard 3.6) and partner with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities in the development of curriculum content and processes (standard 2.5).8 In this context, it can be challenging to appropriately and fairly integrate Torres Strait Islander peoples' history, health, wellbeing, and culture, especially when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are underrepresented as tertiary education staff and allied health professionals.10, 11 Within this broader picture, those of Torres Strait Islander heritage make up 4% of Australia's total 983 700 First Nations population, while those of both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent constitute 4.3%.2, 12

Cultural immersion is a teaching method in which universities partner with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, supporting non-Indigenous academic staff in content delivery through cultural knowledge and lived experiences.7 This can also alleviate the often regular demands placed on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander academic staff within tertiary institutions.7 Cultural immersions for university students have been implemented with success across a range of healthcare professions in Australia and New Zealand.13-15 It has been reported to be effective for enriching dietetics students' understanding of Aboriginal culture and increasing confidence in working with Aboriginal people in a health setting.7 The aim of this study was to describe a standalone Torres Strait (Melanesian) cultural immersion delivered to dietetics students at a large university in Australia and to understand whether cultural immersion supports the development of students' knowledge and skills in relation to specific Dietitians Australia performance criteria.9

2 METHODS

To contextualise this learning activity and subsequent research, a positionality statement is important. BP has cultural ties to the South Pacific and the Torres Strait Islands and is a public health researcher with expertise in Indigenous methodology and decolonising health research and practices. Second author GP is a descendant from the Eastern Torres Strait Islands with direct family lineage to Lifou Island in New Caledonia and West Papua (Province). He has diverse experience across various roles in the areas of health, housing, and education. He has held leadership positions, including the chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Community Advisory Council and Assistant Director with the Office of Northern Australia. Last author AD is an Accredited Practising Dietitian and dietetics academic with experience developing First Nations curriculum content and working with First Nations peoples and communities.

The Torres Strait Islander (Melanesian) cultural immersion was co-designed, analysed, and reported through an iterative process with a Torres Strait immersion educator from the Eastern Islands (GP), a First Nations researcher (BP), and dietetics academic (AD). Utilising longstanding pre-existing relationships, the authors collaborated on the development of the cultural immersion experience. The co-design process took place over an extended period (more than 9 months) leading up to the cultural immersion. The First Nations researcher and dietetics academic yarned with the immersion educator about the topic areas of Torres Strait Islander history, culture, diet, and health and the four performance criteria relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.9 For this cultural immersion, we collectively decided to focus the content on two out of the four performance criteria. The first performance criteria 1.5.4 (Acknowledge colonisation and systemic racism, social, cultural, behavioural, and economic factors which impact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples' health outcomes and how this might influence dietetic practice and outcomes) was selected due to the complexity and the need to incorporate Torres Strait Islander perspectives, including lived and professional experiences in health. The performance criteria 4.1.3 (Engages in culturally appropriate, safe and sensitive communication that facilitates trust and the building of respectful relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples) was selected as it was an interactive learning experience. The performance criteria 1.5.3 (Applies evidence- and strengths-based best practice approaches in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health care, valuing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing) was deemed more appropriate for later in the curriculum when students are formally assessed due to the use of the term ‘applies’. We did not include the performance criteria 1.3.8 (Recognises that whole systems — including health and education — are responsible for improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and collaborates with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and communities to advocate for social justice and health equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples') as it was collectively agreed upon that before whole systems approaches could be understood, students needed to firstly appreciate Torres Strait Islander history, culture, diet, and health. Concepts of social justice and health equity were integrated into the content design of the stations. For the topic area of health, the importance of holistic health, along with health service delivery, health service models and accessibility to healthcare, were discussed during the co-design process and incorporated. The immersion educator then yarned with the dietetics academic and First Nations researcher about their desired content, approach and format of delivery. Table 1 provides an overview of the structure of the day and a description of the content which was developed through yarning about the desired topics and performance criteria during the co-design process. In the final meetings, we yarned about logistics.

| Structure | Description | Dietitians Australiaa |

|---|---|---|

| Opening ceremony | Welcome to Country (organised through the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council), Cultural dance (Kab Kar) and presentation on Torres Strait Islander peoples' history, culture, linguistics, kinship, customary lore, practices, totems, and belief systems. | 1.5.4 |

| Creation stories through weaving station | The cultural immersion educators to share creation stories “Tagai” The Warrior in the Sky (Navigation) and “Gelam” The Man from Moa (Creation of Resources), while students weave an angel fish. An interactive dialogue to be encouraged. | 1.5.4 and 4.1.3 |

| Food preparation station | The cultural immersion educators to yarn about traditional foods, their uses and influence on dietetic practice. Demonstration of the husking and milking of a coconut. Select foods will be pre-prepared for tastings, e.g., Sop Sop (a dish made with root vegetables and coconut milk). An interactive dialogue to be encouraged. | 1.5.4 and 4.1.3 |

| Artefacts and cultural dance station | The cultural immersion educators to display and yarn about an array of cultural artefacts such as the Dhari (headdress), warup (drum), Kulaps (traditional musical instrument), lap lap (traditional garment worn during cultural ceremonies) and traditional costumes and adornments. Students to be taught a cultural dance (We Ka Daiwi), along with the significance and meaning behind each movement. | 1.5.4 |

| Yarning about health station | The cultural immersion educator to yarn about factors which influence and impact Torres Strait Islander peoples' health outcomes, holistic health, health service delivery, systemic racism in healthcare, Aboriginal Medical Services (including MBS 715 health check), Community Controlled Health Services and considerations for safe, sensitive and effective communication. An interactive dialogue to be encouraged. | 1.5.4 and 4.1.3b |

| Closing ceremony | Recap on key learnings of the day. Cohort to participate in the cultural dance from the artefacts and cultural dance station. | 1.5.4 |

- a Dietitians Australia National Competency Standards (performance criteria).

- b Incorporated elements of 1.3.8 Recognises that whole systems—including health and education—are responsible for improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and collaborates with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and communities to advocate for social justice and health equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples'.

The Torres Strait Islander (Melanesian) cultural immersion was held on the university campus in May 2023, over 7 h for first-year Master of Nutrition and Dietetics students. The day commenced with an opening ceremony which included a Welcome to Country, cultural dance (Kab Kar) and presentation. The Kab Kar is a traditional dance of the Meriam people in the Eastern Regions of the Torres Strait Islands (Zenadth Kes). This Kab Kar, performed by the cultural educators from Mer Island (Murray Islands), can only be performed in certain significant settings by those deemed worthy by elders and knowledge holders (Figure 1a).

The students then divided into small groups for four station rotations of creation stories through weaving; food preparation; artefacts and cultural dance; and yarning about health (Figure 1). A description of each station is provided in Table 1. The day concluded with a closing ceremony, which included a recap and the cohort participating in a cultural dance known as We Ka Daiwi (Coconut Song) (Figure 1h).

A mixed methods approach was used to provide context, depth and perspectives. This approach enabled quantitative and qualitative data to be brought together to gain a comprehensive insight into the cultural immersion's impact on student learning. The pre- and post-survey data were integrated with the thematic analysis of focus group interviews. A cyclical approach was applied, where the themes generated by the initial research conducted by the dietetics academic and First Nations researcher were discussed with the immersion educator. This iterative process allowed for ongoing refinement, development and cultural input throughout the reporting process.

Seventy-two first-year Master of Nutrition and Dietetics students were invited to participate. Professional university staff who were not known by the students facilitated the recruitment process by posting advertisements on Canvas, the university's learning management system. This research was conducted and reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines for reporting observational research and the Good Reporting of a Mixed Methods Study guidelines.16, 17 Participation was voluntary and written; informed consent was obtained before the study commenced. The study was approved by The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee, project number 2022/HE000365.

Quantitative process measures were derived from pre- and post-surveys; data collected was hosted and stored on the REDCap data management system.18 The pre-cultural immersion survey included questions on participant demographics and if students self-identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander descent. A set of six pre- and post-questions were developed to assess the impact of the cultural immersion on student knowledge on pre-determined categories of Torres Strait Islander history, culture, diet and health; interest and perceived confidence in working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in a health setting; and interest in placement opportunities in a Community Controlled Health Service. These same questions were used in our Aboriginal cultural immersion.7 Additional questions were included in the post-survey to assess the impact of the cultural immersion on students' understanding of Torres Strait Islander history, culture, diet and health; developing competence for the selected performance criteria (1.5.4 and 4.1.3); as well as recognising holistic health. To inform the delivery of future cultural immersions, questions were also asked around organisation, facilitation and overall satisfaction. The first survey was completed 2 weeks before the students participated in the cultural immersion (File S1), and the second within 1 week after the immersion (File S2).

Qualitative process measures agreed upon during the co-design process were derived from group interviews. A focus group interview guide was developed with eight questions. Questions were asked about the impact on knowledge in pre-determined categories of history, culture, diet and health. Two questions related to performance criteria 1.5.4 and 4.1.3. Further questions were asked on holistic health, the impact on the journey as a dietitian, experiences and perspectives on engagement with each station, and suggestions for improvement (File S3). Students who completed the surveys were also invited to participate in the focus groups. Three focus groups with eight to nine students in each group were conducted face-to-face on campus for an average of 40 min, 1 week after the cultural immersion. The focus groups were conducted according to the methods we have previously published in a companion study evaluating an Aboriginal cultural immersion with the same facilitators and moderators.7 Qualitative focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed via the Otter.ai application. Transcripts were edited by a provisional Accrediting Practicing Dietitian and checked by a dietetic academic. Audio data files and transcripts were stored on the university's secure Research Data Store. Transcripts were de-identified but not returned to participants for any further checking. De-identified transcripts were imported into NVivo (release 1.7.1). Using thematic analysis,19 the data were initially categorised deductively on knowledge gained (history, culture, diet and health), the two DA performance criteria (1.5.4 and 4.1.3), holistic health, and how this experience impacted students' journey as a dietitian. These were then explored inductively to generate themes, forming part of the broader cyclical and iterative approach underpinning the research.

For the quantitative data, Likert scales were used for the pre- and post-survey questions. The median (IQR) and mean Likert score change (SD) were reported. To compare the pre-and post-responses, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test and paired samples test (two-sided) were used. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 28, with significance set at p < 0.05. Descriptive statistics were used for the additional post-survey questions.

3 RESULTS

There were 52 entries for the survey administered prior to the cultural immersion; of these, four students had two entries, and the second entries were removed for consistency. The final sample included n = 48 students (67% response rate); most were female (96%), aged between 20 and 25 years (98%). One student self-identified as Aboriginal. Of the 48 students who completed the surveys, 25 students (52%) participated in the focus groups. The researchers' approach allowed for the situated knowledge of the First Nations authors to be reflected and for a decolonised lens to be applied to the thematic analysis, whereby five themes emerged (Table 2).

| Category | Theme |

|---|---|

| History | Working at the knowledge interface |

| Culture | Working at the knowledge interface |

| Diet and health | Working at the knowledge interface |

| Colonisation and racism (performance criteria 1.5.4) | Reframing the narrative |

| Effective communication (performance criteria 4.1.3) | Experiential learning |

| Holistic health | Community links |

| Impact journey as a dietitian | Promoting reflection |

The cultural immersion improved students' general knowledge of Torres Strait Islander history, culture, and traditional foods, diet and health (Table 3).

| Pre-cultural immersion (median ± IQR) | Post-cultural immersion (median ± IQR) | p-Valuea | Mean Likert score change (SD) | p-Valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate general knowledgec | Torres Strait Islander history (past and present) | 2.00 (1.00) | 3.00 (1.00) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.08) | <0.001 |

| Torres Strait Islander culture (beliefs, customs and values) | 2.00 (1.00) | 3.00 (1.00) | <0.001 | 1.23 (0.97) | <0.001 | |

| Torres Strait Islander diet and health (traditional foods, medicines) | 2.00 (1.00) | 3.00 (1.00) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.00) | <0.001 | |

| Questions | Interest in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healthd | 3.00 (2.00) | 3.00 (1.00) | 0.08 | 0.19 (0.73) | 0.08 |

| Confidence working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in a health settingd | 2.00 (1.75) | 3.00 (1.00) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.92) | <0.001 | |

| Interest in an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service for Placemente | 2.00 (1.00) | 2.00 (1.00) | 0.48 | −0.04 (0.41) | 0.49 |

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

- a Wilcoxon signed rank test.

- b Paired samples test, two-sided.

- c 1 = no knowledge; 2 = a little knowledge; 3 = working knowledge; 4 = sound knowledge; 5 = a lot of knowledge.

- d 1 = not very; 2 = somewhat; 3 = fairly; 4 = very; 5 = extremely.

- e 1 = no; 2 = maybe; 3 = yes.

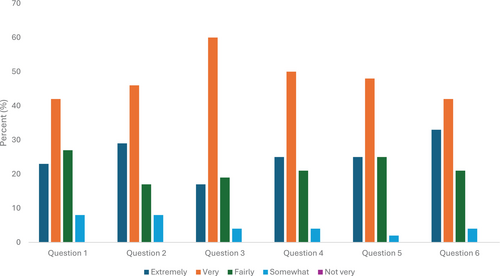

The cultural immersion was ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ effective in helping the students understand Torres Strait Islander peoples' history, culture, and traditional foods, diet and health (Figure 2).

… I really enjoyed the weaving station. I mean, all of them were really, really good. But the weaving station I found really helpful because the weaving allowed it to be a more informal setting. And so, we were able to have conversations with the facilitator, um very informally. I found the creation stories really helpful to understand their culture and how they've been brought up from a young age as well (Participant 10)

… I found the food station really interesting. I mean, getting to taste, what they kind of eat day in, day out and learning about coconuts. How important they are in their daily life as well not just food, but say birthing as well with the coconut oil and how it's put-on babies when they're first born and just how integrated it is into their daily lives (Participant 16)

… Another interesting aspect was that we were learning how integrated food is in their culture. So, we learned about the fact like the celebrations ‘Coming of the Light’ which was celebrating Christianity's arrival to the Torres Strait that they celebrate that with a reenactment but also, they cook traditional foods in their underground oven [Kup Murri], and then they share that amongst the community. So that knowing the ways that food is used to celebrate their culture as well was quite interesting (Participant 12)

… I think it was really helpful throughout the whole yarning and all the other activities as well and then at the very start, they kind of touched on quite a lot of their history and how it came to be and the struggles that they face as a peoples', I don't know in the past, I think that was pretty interesting. They just kind of said it in a way like oh, I'm not judging you or what your ancestors did, or that kind of thing, but just acknowledged it and said, this is why our people feel this way or is this how we have gotten to where we are now. […] (Participant 16)

… So, when we were in the yarning session, they were talking about how there aren't huge amounts of health services in the Torres Strait and so often, they have to be flown out and that can cause a lot of trauma. Because sometimes then those people don't come back. And so rather than, you know, trying to change necessarily what they think of health professionals but acknowledging why they're thinking what they're thinking, rather than just writing it off (Participant 10)

… I think yeah, yarning was definitely the big thing that, rather than just, I mean, we learned about it saying, you know, it's good to do the yarning but to actually do it was a lot different. I think it's not what I expected. It was a lot more conversational. A lot less structured. I think it's something that's definitely important to actually physically do and not just learn about, I think it was really good (Participant 13)

… […] he was saying when his, I think it was his [relative] was about to pass away and she like mimicked her totem which I think was very, like something that obviously is only like to their culture in like Aboriginal and Torres Strait culture, where they have a totem, and that they respect that animal and it's like throughout their life that they always connect with that totem. It's just really interesting to see how even when, um like the last second when she was about to pass away, she had that spiritual connection with her totem. And I think that's something really different from like, you know, like our community, the Western community where it's not like we don't have like anything that would symbolise or anything that's remotely similar to that. Which I think was like a big, um like, contribution to their perspective of community, sorry not community, ah health (Participant 28)

… […] I think similar to [participant name], definitely makes you like reflect back on your own culture as well. Like, for example, one similarity between my culture and their culture is that we both have like that respect for the elderly and we always kind of, um try to incorporate their opinion on their sort of views before we make any big decisions (Participant 26)

The cultural immersion improved students' perceived confidence working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in a health setting (mean change [SD]: 0.73 [0.92]; p < 0.001). No change was reported in student interest in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (mean change [SD]: 0.19 [0.73]; p = 0.08) or interest in a Community Controlled Health Service for placement (mean change [SD]: −0.04 [0.41]; p = 0.49) (Table 3).

Students were ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ satisfied with the cultural immersion (96%) and would recommend the day to other dietetics students (100%). The cultural immersion was ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ well organised (86%), and the immersion educators contributed ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ positively to their cultural immersion experience (94%).

4 DISCUSSION

This novel paper embeds Torres Strait Islander people's history, culture, diet and health into the curriculum through a standalone Torres Strait (Melanesian) cultural immersion. This improved students' knowledge of Torres Strait Islander history, culture, diet and health through working at a knowledge interface and was expressed to be ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ effective for students to develop competency in performance criteria 1.5.4 through reframing the narrative and 4.1.3 through experiential learning. The cultural immersion impacted students' journey as dietitians by promoting reflection and increasing their perceived confidence in working with Torres Strait Islander populations in a health setting.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health educational content contributes to an important area of practice within dietetics and other allied health disciplines.10, 11 Although there is a lack of explicit curriculum scholarship guiding approaches to the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge in higher education,20 approaches that foster face-to-face interaction with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander educators have been shown to be a critical element in cultural education.21 As an interactive learning experience, cultural immersion provides direct supervised interactions,22 which helps to equip students with essential skills for respectfully engaging and communicating with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, families and communities,22 while enhancing cultural knowledge and sensitivities.23 As a cultural learning experience, Torres Strait Islander dance, song and art play a crucial role in cultural expression and knowledge transmission.24, 25 Practices shared within cultural immersions are more than just fun activities; they convey deep understandings of astronomy, environment, social structure and community identity.25, 26 Dance and music are also integral to formal and informal education, offering ways to communicate values, beliefs and worldviews that differ from Western knowledge systems.2, 24

It is important to recognise that cultural immersions are one teaching method within an integrated suite of education strategies to support the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health competencies.7 In this context, immersive experiences should be co-designed with intent to strategically align with learning outcomes purposely for progressive developments.7, 27 Our previous Aboriginal cultural immersion was positioned early as a first progressive stage in the dietetics curriculum, introducing processes of learning through Indigenous pedagogies and focusing on building cultural awareness.7 This was shown to increase self-efficacy and the students' perceived confidence working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in their journey as a future dietitian. This Torres Strait Islander cultural immersion formed part of an assessment and was positioned in our curriculum after students had received foundational educational content around history, culture, determinants of health, ways of working with communities and traditional foods. It was focused on moving students through the progressive stages of thinking for cultural safety28 and support the development of competence (DA performance criteria).9 The impact this had on students' journey as a dietitian was promoting reflection. Turning the health lens to self-enquiry is a foundational shifting process in the continuum of cultural learning28 for individuals to possess the competence and self-awareness necessary to examine their own privileges, discomforts, assumptions and to adopt new ways of thinking.11 Developing student reflexive practices should then be further built upon through an integrated curriculum so that as future health professionals, graduates can create more culturally safe and respectful environments, improving the quality of care and outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.29

The findings from this cultural immersion indicated that while the perceived confidence working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in a health setting increased, there was no change in interest in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health or placement, similar to the findings of our previous Aboriginal cultural immersion.7 While this is important, it is essential to reiterate that these immersions were designed to be positioned early (year 1) and are learning activities among many throughout our curricula. Placement opportunities have been shown to foster interest in working with Aboriginal communities.30 To further understand the impact of an integrated Indigenous curricula, considerations for longitudinal research should be considered, evaluating the qualities and attributes of graduates.

Ensuring that curricula meet accreditation and competency standards is complex,27 and there are additional layers of intricacy when embedding an integrated Indigenous curriculum. For example, this immersion experience was aligned with key performance criteria,9 which necessitated a longer and more intensive process of co-design. This cultural immersion was iterated over 9 months and supported by an immersion educator with extensive experience working in health and education. In this situation, the authors' pre-existing relationships facilitated this process; however, within the wider scope, this can be challenging to secure appropriate people with the skills and cultural authority to deliver such content, in addition to considering remuneration.31 Given university funding is often limited, and while monetary remuneration is important, from lived experience, it is not the sole exchange prioritised for communities. The concept of reciprocal relationships and values that Indigenous knowledge systems emphasise, such as sharing, respect and sustainability must be appreciated.32 Exploring innovative conjoint solutions, such as providing workshop training and upskilling opportunities for future emerging community leaders, can be beneficial. In turn, this may also provide opportunities and pathways to further transition into tertiary or higher degree education.

The maintenance of partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and local community-controlled organisations and services is also key to success.33 This ensures that training is appropriate for the surrounding communities,21 it supports program longevity15 and provides stability for university timetabling. For instance, if individual immersion educators are needing to attend to cultural obligations (such as Sorry Business), organisations have the ability to respect these cultural commitments by allowing other staff members to provide coverage. A successful cultural immersion program highlighted the importance of organisational partnerships and while they encountered staffing turnover from the partnering organisations and individual educators, their program has been ongoing for more than a decade.15 As highlighted in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Framework28 and our previous work,7 implementation of such work requires sustained funding and resource allocations.

It is important to reiterate that we are not specifically advocating for the inclusion of cultural immersion in dietetics programs per se but rather for the incorporation of experiential and interactive learning experiences with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities. This relates to the National Competency Standards collaborative practice domain (Domain 4)9 and key concepts outlined in the concept-based approach to dietetic curriculum design.34 Equally important is the involvement of community members, as they reflect the populations students are likely to engage with beyond tertiary education. While it is suggested in the National Competency Standards guide9 that ‘there is no expectation that all students will have had an experience with an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander client or community in practice and that simulated or other learning experiences that support learning would be appropriate’, this study highlights the importance of interactions for reflective practice that is essential to working appropriately and effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities. While this immersive experience was aligned to performance criteria 1.5.4 and provided students with the opportunity to learn about history, colonisation and systemic racism from a Torres Strait Islander perspective, it must be acknowledged that a single learning activity cannot fully address the depth and complexity of this competency, and there should be integration of this performance criteria throughout the curriculum. It is also important to highlight that the elements to this performance criteria have been previously described as uncomfortable.35 However, the approach taken by the immersion educators fostered an inclusive and supportive group environment, enabling open and honest dialogue around challenging topics. The collective engagement marked an important step in the group's process of ‘acknowledging’ a key aspect of this criterion.

The strengths of this study were that the cultural immersion was co-designed with a Torres Strait immersion educator and a First Nations researcher (standard 2.5),8 with the immersion educators having extensive experience working in the First Nations health, education sectors and leadership roles within their communities. We ensured quality improvement by integrating student recommendations from our Aboriginal immersion, such as incorporating a closing ceremony to recap and consolidate knowledge learned. This study offers a practical example demonstrating how competencies can be translated into tangible learning experiences.36 The mixed-methods study design offered a comprehensive and complete understanding of the data. This study is not without limitations. The sample size was limited to the number of students in the cohort, and as the study was voluntary, not all the cohort participated in the surveys and focus groups. While questions relating to perceived confidence and interest were collected in survey data, these were again not explored in focus groups, which could be addressed in future research to extend the evidence base. Though students appreciated the practical elements in the food preparation station, using experiential learning to involve them throughout the entire process would be beneficial (e.g., preparing a Kup Murri — underground cooking). Feedback also indicated a desire to try more traditional foods discussed during the food preparation station.

In conclusion, by incorporating Torres Strait Islander knowledges in our dietetics curricula, students were able to gain appreciation of Australia's First Nations groups. This cultural immersion enriched dietetics students' understanding of Torres Strait Islander history, culture, diet and health. Cultural immersion is one teaching method that can be used within an integrated suite of education strategies to support the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health competencies. Sustainability requires university commitment and funding allocation. The concept of reciprocal relationships and values that Indigenous knowledge systems emphasise must be appreciated, and innovative solutions explored.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

BP, GP, and AD contributed to the co-design of the cultural immersion. BP and AD conceived the study. BP, AR, MA-F, and AD contributed to the methodology. AD, JC, JV, MN, MI, and JWCC collected the data. AD conducted the quantitative analysis. BP, GP, and AD conducted the qualitative analysis. BP, LE, and AD drafted the manuscript. GP, AR, MA-F, JC, MN, MI, JV, JWCC, and MD contributed to the review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Two Footprints Indigenous Corporation and cultural educators and performers; Mrs. Trudi Passi, Mr. Xavier Passi, Mr. Genus Passi Junior, Ms. Aba Bero, Ms. Velma Gara, Miss Patrina Gara, Mr. Sella Dow, Mr. Rod Watkins, Mr Andrew Malloch and Mr. Tomas Dow.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (project 2022/365).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.