Implications of the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism for Fertiliser and Food Markets

Conséquences du mécanisme d'ajustement carbone aux frontières de l'Union européenne pour les marchés des engrais et des produits alimentaires

Auswirkungen des EU- CO2-Grenzausgleichssystem auf die Düngemittel- und Lebensmittelmärkte

Summary

enCoherence in policy approaches across countries is crucial for achieving common GHG emission reduction goals at lower costs. Agro-economic models like Aglink-Cosimo, including global fertiliser markets, are useful for analyzing the anticipated effects of GHG reduction policies on food commodity markets. These policies can significantly affect domestic industry competitiveness, either positively or negatively. Such assessment tools can enhance evidence-based policy discussions and formation. We include in the baseline a EU ETS carbon price on fertiliser production in the EU as of 2026, without free allowances at 100 USD/tonne of CO2-eq emitted. Carbon pricing is assumed to be applied by the EU, Canada and the USA to fertiliser production from 2026 onwards.

The results of the analysis presented in this article indicate that a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) significantly impacts fertiliser trade. A unilateral CBAM tariff affects EU fertiliser trade more than a common CBAM tariff adopted by a coalition of countries. These effects depend heavily on the volume of bilateral trade within club countries. Fertiliser markets influence commodity production and prices modestly due to the price inelasticity of fertiliser demand by farmers and the buffering role of trade in response to price shocks. In terms of GHG emissions, a climate club scenario results in lower total world emissions compared to a unilateral CBAM scenario.

Abstract

frLa cohérence entre pays des approches pour l'action publique est essentielle pour atteindre des objectifs communs de réduction des émissions de gaz à effet de serre (GES) à moindre coût. Les modèles agroéconomiques comme Aglink-Cosimo, qui comprennent les marchés mondiaux des engrais, sont utiles pour analyser les effets anticipés des politiques de réduction des GES sur les marchés des produits alimentaires. Ces politiques peuvent affecter de manière significative la compétitivité de l'industrie nationale, de manière positive ou négative. De tels outils d'évaluation peuvent améliorer les discussions et la formulation de politiques fondées sur des données probantes. Dans le scénario de référence, nous incluons à partir de 2026 un prix du carbone du système communautaire d'échange de quotas d'émission (SCEQE) sur la production d'engrais dans l'Union européenne (UE) à 100 USD/tonne d'équivalent CO2 émis, sans quotas gratuits. L'UE, le Canada et les États-Unis sont supposés appliquer la tarification du carbone à la production d'engrais par à partir de 2026.

Les résultats de l'analyse présentée dans cet article indiquent que le mécanisme d'ajustement carbone aux frontières (MACF) a un impact significatif sur le commerce des engrais. Un tarif MACF unilatéral affecte davantage le commerce des engrais de l'UE qu'un tarif MACF commun adopté par une coalition de pays. Ces effets dépendent fortement du volume des échanges bilatéraux au sein des pays membres du club. Les marchés des engrais influencent modérément la production et les prix des matières premières en raison de l'inélasticité de la demande d'engrais par les agriculteurs et du rôle tampon du commerce en réponse aux chocs de prix. En termes d’émissions de GES, un scénario de club climatique se traduit par des émissions mondiales totales inférieures à celles d'un scénario de MACF unilatéral.

Abstract

deDie Abstimmung politischer Ansätze zwischen den Ländern ist entscheidend für das Erreichen gemeinsamer Treibhausgasminderungsziele unter Geringhaltung der Kosten. Agrarökonomische Modelle wie Aglink-Cosimo, die auch die globalen Düngemittelmärkte abbilden, sind nützlich für die Analyse der zu erwartenden Auswirkungen von Maßnahmen zur Treibhausgasminderung auf die Lebensmittelmärkte. Diese Maßnahmen können die Wettbewerbsfähigkeit der heimischen Industrie erheblich beeinflussen: entweder positiv oder negativ. Solche Bewertungsinstrumente können faktenbasierte politische Diskussionen anstoßen und die Politikgestaltung verbessern. Wir gehen von einem EU-ETS-Kohlenstoffpreis für die Düngemittelproduktion in der EU ab 2026 aus, ohne kostenlose Zertifikate in Höhe von 100 USD/Tonne emittiertem CO2-Äq. Es wird davon ausgegangen, dass die EU, Kanada und die USA ab 2026 eine Kohlenstoffbepreisung auf die Düngemittelproduktion anwenden werden.

Die Ergebnisse der in diesem Artikel vorgestellten Analyse zeigen, dass das CO2-Grenzausgleichssystem (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism - CBAM) erhebliche Auswirkungen auf den Düngemittelhandel hat. Ein einseitiger CBAM-Zoll wirkt sich stärker auf den EU-Düngemittelhandel aus als ein gemeinsamer CBAM-Zoll, der von einer Koalition von Ländern beschlossen wird. Diese Auswirkungen hängen stark vom Volumen des bilateralen Handels innerhalb der Clubländer ab. Die Düngermärkte beeinflussen die Rohstoffproduktion und die Preise nur geringfügig, da die Düngernachfrage in der Landwirtschaft preisunelastisch ist und der Handel als Puffer bei Preisschocks dient. In Bezug auf die Treibhausgasemissionen führt das Szenario des Klimaclubs im Vergleich zu einem einseitigen CBAM-Szenario zu niedrigeren Gesamtemissionen weltweit.

Introduction

The European Union's (EU) Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will enter its ‘definitive regime’ in 2026. EU importers of certain energy intensive goods and electricity will be required to purchase certificates covering the carbon content embedded in the imports of these goods at the weekly average auctioned price (i.e. carbon price) from the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). An important good covered by the CBAM is mineral fertiliser. In the analysis presented in this article we make use of an agricultural commodity model (see Box 1 for Methodology) to assess the potential impacts that the CBAM may have on production, use and trade of fertiliser and food, with emphasis on critical issues such as reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and carbon leakage. Under stringent climate policy, incentives may exist to relocate production to countries with laxer policies and higher emission intensity resulting in ‘carbon leakage’. We also address the implications of extending the CBAM to a set of countries with a similar policy in place, which is referred to as a CBAM club (or climate club) in the literature.

The main findings from the analysis are that a unilateral EU CBAM leads to moderately higher domestic fertiliser prices translating into modest agricultural EU and world market impacts. One third of EU reduced agricultural emissions will be leaked, meaning that they are emitted in connection with higher production in international agricultural markets. A CBAM club will have lower trade-distorting effects than a unilateral CBAM depending on bilateral trade. In terms of leakage, two thirds of CBAM club countries’ GHG emission reductions from agricultural production are instead leaked outside the club.

The EU ETS and CBAM

Since its launch in 2005, companies in highly-emitting sectors under the EU ETS must acquire emission allowances for every tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-eq are calculated on the basis of Global Warming Potentials over 100 years) emitted or they face large fines.

GHG emissions in the EU decreased by 30 per cent from 1990 to 2021 (EEA, 2023) while embedded net imports (imports minus exports) of CO2 emissions per capita have increased by 23 per cent over the same period (Global Carbon Budget, 2023).

The EU ETS will increasingly reduce the number of permits and free allowances to contribute to achieving EU emission targets, potentially raising carbon prices, compliance costs and the risk of carbon leakage.

To address this problem, the EU introduced the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which will act as an import tariff on GHG emissions embedded in particularly carbon-intensive imports, one of which is mineral fertiliser. The CBAM entered a transitional phase on 1 October 2023, but actual payments will only be required starting in 2026. From 2026, under its definitive regime, importers will have to acquire CBAM certificates equivalent to the GHG emissions embedded in the products exported to the EU minus any carbon price imposed domestically by the countries exporting to the EU. This ensures, in principle, that EU imports will be subject to an emission taxation equivalent to the EU level.

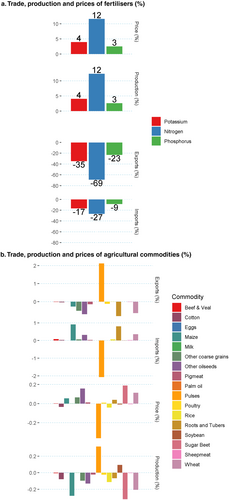

Effects of the EU CBAM on fertiliser imports

As the EU is a net importer of fertilisers, the introduction of a unilateral CBAM on imports is expected to raise domestic fertiliser prices. However, the incidence of the price increase on producers and consumers will depend on the relative responsiveness of supply and demand, and the degree of trade openness. In order to isolate the impact of a unilateral EU CBAM, we perform an ex-ante analysis where we compare this policy against a baseline in which domestic carbon pricing is already implemented (i.e. CBAM policy versus a baseline including the EU ETS with no free allowances). Model estimates suggest that a unilateral CBAM tariff on EU fertiliser imports will increase fertiliser domestic producer price, stimulate domestic production and decrease reliance on imported fertilisers. Results depend on the carbon price and carbon intensities assumed for the EU and its main trading partners. With an assumed international carbon price of 100 USD/t, EU imports of NPK (Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium) fertilisers (all fertiliser quantities and prices are expressed, in our model, in terms of the main nutrients included in the fertilisers) are estimated to decline (by –27 per cent, –9 per cent, and –17 per cent, respectively) by 2040 (Figure 1a). Domestic EU fertiliser producer prices are, in turn, expected to rise (by 12 per cent for N, by 3 per cent for P, and by 4 per cent for K respectively). EU fertiliser production will increase by a similar amount and lower import demand in the EU, so that international fertiliser prices will not be affected much (–1 per cent for N and less than –0.5 per cent for P and K).

Unilateral EU CBAM scenario vs baseline in the European Union, 2040

Source: Authors’ simulations based on OECD/FAO (2023a).

Higher EU fertiliser prices lead to modestly lower use in the scenario (less than 1 per cent) and, thus, lower crop production in the EU (except for nitrogen fixing crops), with consequent impact on both domestic and international crop prices. However, the impacts on EU agricultural commodity markets are quite modest (Figure 1b). Slightly lower agricultural production leads to slightly higher domestic prices with lower exports and higher imports in the range of ±2 per cent. EU prices of most agricultural commodities increase (although by less than 0.5 per cent), given the lower EU fertiliser use and production (less than 0.5 per cent in absolute value). To compensate for the lower domestic production of fertilisers, imports increase and exports fall, especially of the fertiliser intensive commodities with more negative production effects (e.g. maize).

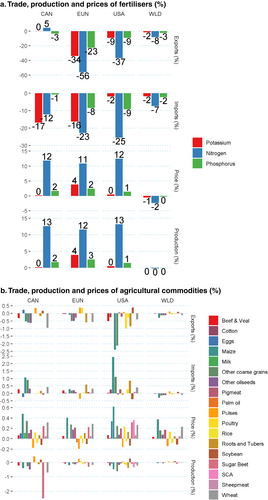

A ‘CBAM club’ mitigates impacts

Other countries may also consider implementing a CBAM to balance market competitiveness issues arising from their climate mitigation action (EC, 2021). In addition, main EU foreign trade partners will realise that CBAM revenue accrued to the EU is foregone revenue in their countries. This realisation may incentivise more countries to adopt similar climate ambition. The formation of a ‘CBAM climate club’, may limit the incentives to trade with countries which take no or more limited climate mitigation action. We implement a model scenario to study the impacts of extending the EU CBAM framework to other trade partners who have similar emission taxes in place, such as Canada and the United States (Box 1). The effects are similar to the EU unilateral case (Figure 2) but price effects are muted given that some of the Club members are main global traders in fertilisers (e.g. Canada in K). In the club countries, the CBAM disincentivises imports from non-club members. To the extent that bilateral exports can be diverted from other destinations to buffer demand within club countries, fertiliser price increases are reduced.

CBAM Club scenario vs baseline in the European Union, 2040

Source: Authors’ simulations on OECD/FAO (2023a).

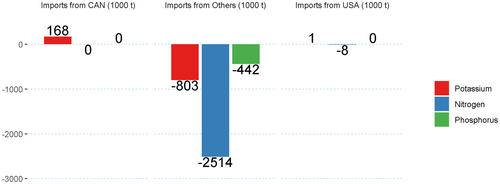

Trade between countries is affected by the carbon prices (and emission permits) faced by fertiliser producers in each of the club countries. As the largest net importer among club members, the EU faces the largest adjustment for all fertilisers. Fertiliser prices in the USA and Canada are less affected for P and K. These impacts illustrate that price impacts for P and K are different among trade partners as the EU imports more potassium from Canada, but reduces imports of N from the USA, due to relative competitiveness. EU imports of fertilisers from non-bilateral trade partners are reduced (Figure 3).

Bilateral trade in fertilisers, CBAM Club vs baseline (1000 t), 2040

Source: Authors’ simulations on OECD/FAO (2023a).

The primary impact of the CBAM climate club is on trade. Specifically for the EU, total imports and exports are less affected compared to the scenario with a unilateral CBAM.

Due to the climate club design, potassium trade is diverted from countries outside the climate club to countries within the club, since bilateral trade partners have a competitive advantage.

Drops in exports and imports are smaller for the climate club scenario than for the unilateral CBAM scenario, especially for nitrogen. There is almost no difference among scenarios in the case of phosphorus and potassium. Prices and production in the EU are increased slightly less in the climate club scenario than in the unilateral CBAM as bilateral imports among club members satisfy internal demand.

The results for most agricultural commodities show generally lower absolute effects on production, and lower imports and exports in the climate club scenario than in the unilateral CBAM, resulting in larger price effects.

In general, the climate club scenario indicates a lower impact on EU fertiliser production, and higher imports and especially exports compared to the unilateral CBAM scenario, thus implying a lower disruptive effect on trade.

A ‘CBAM Club’ reduces emissions more than a unilateral CBAM

Compared to the baseline, a unilateral EU CBAM increases EU emissions from higher fertiliser production (see CBAM scenario in Figure 4a). This is more than offset by the drop in such emissions in the rest of the world though, resulting in an estimated net reduction (–1,224 kt CO2-eq) in global emissions from fertiliser production (Figure 4a). However, higher EU fertiliser prices induce a reduction in domestic EU agricultural commodity production and increases in commodity production and emissions abroad (see Figure 4b). GHG emissions in the world (from use of fertilisers, and changes in land area and animal numbers) are marginally lower than in the baseline by –214 kt CO2-eq (Figure 4b). Summing all contributions from fertiliser production and consumption, changes in land area and animal numbers, the EU unilateral CBAM decreases total world level emissions by –1,439 kt CO2-eq (see CBAM scenario in Figure 4c).

The climate club scenario implies higher emissions than in the baseline in the EU, USA and Canada from increased fertiliser production (Club scenario in Figure 4a). In the EU, the emission increase is not as much as in the unilateral CBAM scenario because part of the production is replaced by imports from bilateral trade partners. These emission increases are more than offset by decreases in fertiliser production in the rest of the world though. Global emissions from fertiliser production in the climate club scenario are therefore lower by –2,642 kt CO2-eq (Figure 4a). The opposite effects in emissions derive from fertiliser use, change in land use and animal numbers (Figure 4b). A reduction in agricultural production in the EU, in Canada, and in the USA implies reductions in emissions of approximately –317 kt CO2-eq for the EU and of –987 kt CO2-eq for the USA and Canada together. This decrease is offset by emissions leaked to the rest of the world (854 kt CO2-eq), which is approximately 65 per cent of the reduction in club countries. Summing these numbers together, in the climate club scenario, the world has a reduction in GHG emissions from fertiliser use, change in land area, and animal numbers of around –450 kt CO2-eq which is more than twice as much as the reduction from a unilateral CBAM policy (Figure 4b).

In the climate club scenario, the higher decrease in GHG Emissions from fertiliser production in the rest of the world and consequent drop in total emissions (Figure 4a) is compounded by the agricultural market effects (Figure 4b), which implies that, all in all, in the world (Figure 4c), global GHG emissions from a climate club scenario decrease more than in the unilateral CBAM (–3,092 kt CO2-eq in the climate club scenario instead of –1,439 kt CO2-eq in the unilateral CBAM). This larger decrease is mostly due to emission decreases in the non-club members (from fertiliser production) not completely offset by the increases in fertiliser production emissions in club members, thanks to lower Global Warming Potential Intensities.

Conclusions and discussion

Coherence of policy approaches across countries is important for achieving shared GHG emission reduction goals. Models are helpful in assessing the ex-ante effects of policies intended to lower GHG emissions, given that some of these policies may seriously affect domestic industry competitiveness, either positively or negatively. The results of the current analysis show the considerable effect of CBAM on fertiliser trade and GHG emissions. They also indicate potential benefits of a wider CBAM club. The results do depend critically on market characteristics, such as net trade balances, and for a club, the extent of bilateral trade among members. Furthermore, elasticities of supply and demand, as well as of trade, have a critical influence on estimated effects. Fertiliser markets affect agricultural production and prices modestly due to the inelastic fertiliser demand by EU farmers. A unilateral EU CBAM is estimated to increase domestic emissions, reduce carbon leakage, and modestly reduce global emissions. A CBAM climate club scenario lowers total world emissions more than twice that of a unilateral CBAM scenario.

Several caveats to this research should be noted. The EU CBAM also applies, in principle, to products derived from the ones on which CBAM applies directly. It is yet unclear to the authors how this provision applies to fertilisers. Moreover, the current scope of the EU CBAM may be widened to include more sectors directly, such as agricultural and food production, especially if an ETS were extended to those sectors. The low effects on the agricultural commodity markets originate from a specific set of elasticities and assumptions about carbon prices. Even though leakage is observed, low agricultural market reactions imply that emission increases in the rest of the world are not enough to offset the decreases in CBAM countries, thus implying a total decrease in global emissions from agricultural markets. Moreover, drops in agricultural production derived from increases in fertiliser prices may be critical for a portion of farmers that are barely making a profit, thus potentially driving these farmers into debt or completely out of the market. GHG intensities from production of fertilisers are assumed not to change in the period analyzed while they might change in reality due to technological improvements incentivised by CBAM. It is also critical to remember that these results are obtained by comparing scenario results with a baseline already including a carbon price but not including free allowances for fertiliser producers. Additionally, the results are contingent on the evolution of carbon prices in the future. We execute a sensitivity analysis with carbon prices at 50 and 200 USD/t. The results remain qualitatively the same proportionally, while, in absolute terms, there are stronger effects for larger carbon prices. Finally, our analysis focuses on a CBAM on fertilisers while analyses including a CBAM on agricultural goods may obtain different results (Fournier Gabela et al., 2024).

Box 1. Methodology

Our analysis is based on a large-scale recursive-dynamic partial equilibrium model called Aglink-Cosimo (OECD, 2023a; OECD, 2023b; Pieralli et al., 2022), extended to include the global fertiliser sector (Adenäuer et al., 2024) to assess the impacts on agricultural production, trade, consumption and GHG emissions. Data used in the model are from the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook (2023a). In the baseline, the fertiliser trade for the EU, USA and Canada is decomposed into bilateral trade flows (imports and exports) between each of the bilateral partners (EUN, USA and CAN) and the rest of the world (ROW). Imports from partners are modelled explicitly, while exports are simply the imports determined in the ‘mirror’ country. We include in the baseline an EU ETS carbon price on fertiliser production in the EU as of 2026, without free allowances. Carbon prices domestically are applied to production of fertilisers, but not to consumption. It is assumed that the carbon price will be 100 USD/tonne of CO2-eq emitted, similar to prevalent EU ETS prices in early 2023. Carbon pricing is assumed to be applied by the EU, Canada and the USA to fertiliser production from 2026 onwards. Stepanyan et al. (2023) imply that 100€/t CO2-eq would be the carbon price necessary for greenhouse gas emissions to reduce in line with 2030 climate targets. The Danish government showed that a 100€/t CO2-eq tax by 2030 will decrease emissions by 45 per cent compared to 1990 levels (Danish Council on Climate Change, 2023).

The assumptions on fertiliser production emission intensities and the carbon price are at the core of the results. Fertiliser trade data for the EU, USA and Canada from Trade Data Monitor (TDM) have been allocated to fertiliser nutrients. Each exporter to the EU will be responsible for declaring the intensity of products traded and for obtaining the required amount of CBAM certificates. In the model, global warming potentials (GWPs) per tonne of produced fertiliser nutrients (i.e. the GWP intensities or GWPI) are calculated on the basis of Vidovic et al. (2023) and, where not available, from Hoxha and Christensen (2018) and Bentrup et al. (2018). Given estimated warming potential intensities for N, P and K (Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium) at 2.62, 0.45 and 0.517, respectively, calculated ETS permits of about 265 EUR/t of N, 46 EUR/t of P and 52 EUR/t of K respectively are applied to EU fertiliser nutrient production. Given different global warming potential intensities of Canada and the USA, calculated ETS permits of about 378 CAD/t for N, 62 CAD/t for P, and 60 CAD/t for K are applied to Canada fertiliser production and of about 300 USD/t for N, 34 USD/t for P, and 32 USD/t for K to USA fertiliser production. On the other hand, in our model, the rest of the world does not apply any regulation to fertiliser production.

Forming a climate club among members adopting the same carbon price would make imposing CBAMs against each other redundant. We hypothesise that other countries could, in principle, adopt similar policies forming in this way what can be referred to as a ‘climate club’. We model bilateral trade equations only among three jurisdictions: the EU, USA and Canada. The choice of countries is justified because, in 2022, the USA was the EU's fifth-ranked supplier of nitrogen, and Canada was its first supplier of potassium fertilisers. The club represents 24 per cent, 6 per cent and 15 per cent of global N, P and K production, respectively (in 2021). The corresponding shares of world imports are 29 per cent, 17 per cent and 31 per cent.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the European Commission.

Further Reading

A multilateral CBAM would have lower trade-distorting effects than a unilateral CBAM, while reducing global greenhouse gas emissions twice as much.

Un mécanisme multilatéral d'ajustement carbone aux frontières aurait moins d'effets de distorsion sur les échanges qu'un mécanisme unilatéral, tout en réduisant deux fois plus les émissions mondiales de gaz à effet de serre.

Ein multilaterales CO2-Grenzausgleichssystem hätte geringere handelsverzerrende Auswirkungen als ein unilateraler Mechanismus und würde die globalen Treibhausgasemissionen doppelt so stark reduzieren.